No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

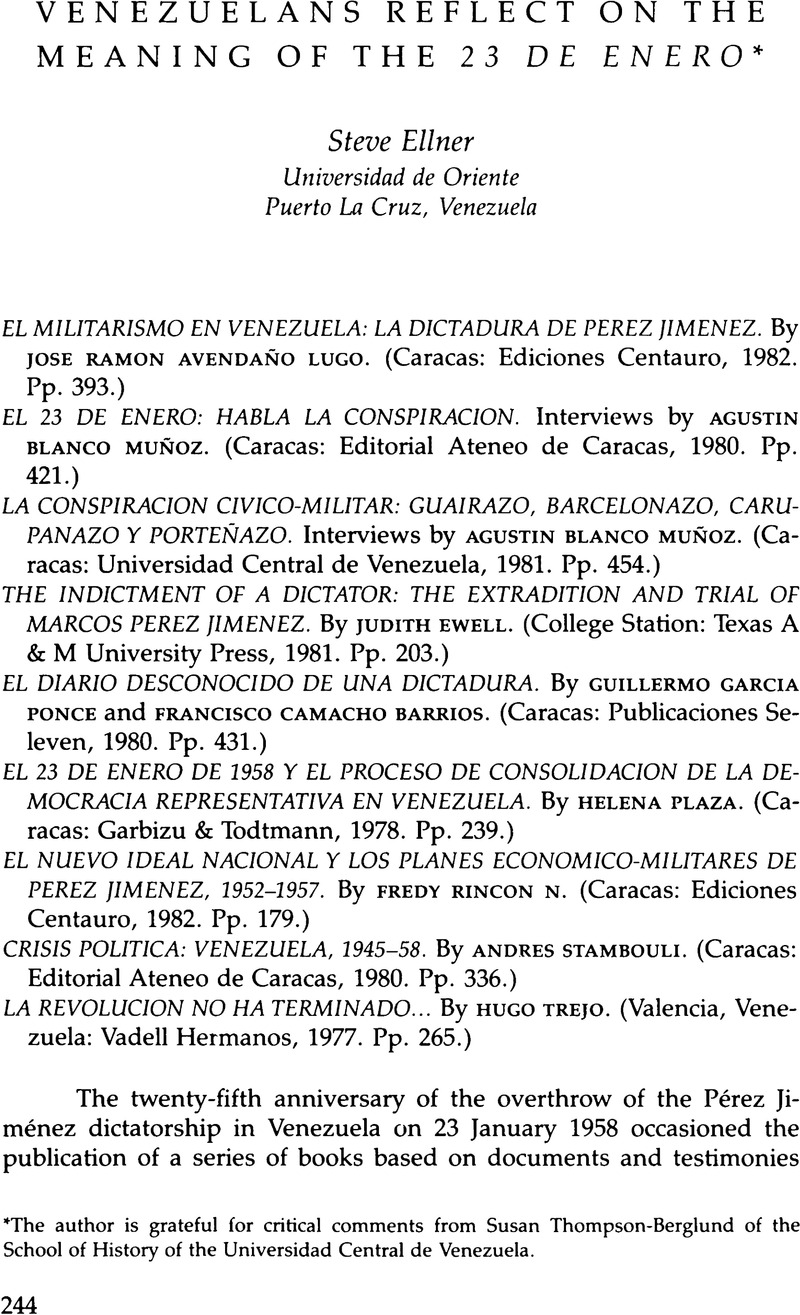

Venezuelans Reflect on the Meaning of the 23 de enero

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1985 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

The author is grateful for critical comments from Susan Thompson-Berglund of the School of History of the Universidad Central de Venezuela.

References

Notes

1. Three books not included in this essay are these recently published works: Fuentes para el estudio del 23 de enero de 1958 (Caracas: Congreso de la República, 1984); Poesía en la resistencia (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1982); and 1958 en la caricatura política, compiled by Paciano Padrón (Caracas: Comisión Bicameral Especial para la Conmemoración del XXV Aniversario del 23 de enero de 1958, 1983). José Agustín Catala has compiled and published numerous documents and articles of the period. Catalá, who was jailed by the Pérez Jiménez government because of his role in the publication of the AD document Libro negro, heads the publishing firm of Ediciones Centauro.

2. Blanco Muñoz, La conspiración cívico-militar, p. 64; Victor Hugo Morales, Del Porteñazo al Perú (Caracas: Editorial Domingo Fuentes, 1971), p. 36.

3. John D. Martz, Acción Democrática: Evolution of a Modern Political Party in Venezuela (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966), p. 93; Winfield J. Burggraaff, The Venezuelan Armed Forces in Politics, 1935–1959 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1972), p. 146.

4. In Blanco Muñoz's El 23 de enero: habla la conspiración, questions are posed regarding the internal debt on pp. 133, 199, 224, 286, and 336. According to one interviewee, the decision of Military Junta President Wolfgang Larrazábal to pay off these debts, which amounted to two billion bolívares, was opposed by a large number of military officers.

5. Both García Ponce and Sáez Mérida favored a strategy in the 1960s of building up leftist contacts in the military in order to trigger a response in the armed forces in opposition to the AD government. It is thus understandable that they would emphasize leftist influence in the planning of the military uprisings of 1962, although other accounts downplay the role of the leftist parties. See Luigi Valsalice, Guerrilla y política: curso de acción en Venezuela 1962/69 (Buenos Aires: Editorial Pleamar, 1975), pp. 23–30; Steve Ellner, “Political Party Dynamics and the Outbreak of Guerrilla Warfare in Venezuela,” Inter-American Economic Affairs 34, no. 2 (Autumn 1980): 10–12; Blanco Muñoz, La lucha armada: hablan cinco jefes (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1980), p. 362; Blanco Muñoz, La lucha armada: la izquierda revolucionaria insurge (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1981), pp. 118–19, 146–47; Guillermo García Ponce and Francisco Camacho Barrios, El diario desconocido de una dictadura (Caracas: Publicaciones Seleven, 1980), p. 299 (this book was republished by Ediciones Centauro in 1982 under the title Diario de la resistencia y la dictadura, 1948–1958).

6. Daniel H. Levine, “Venezuela since 1958: The Consolidation of Democratic Politics,” in The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Latin America, edited by Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), p. 86.

7. José Agustín Catalá, interview, Caracas, 4 August 1983.

8. The 24 November 1948 coup was simplistically viewed during the 1950s as the work of power-hungry officers, epitomized by Pérez Jiménez, while democratic military personnel were credited with a key role in the 23 January movement. Anyone who holds to this framework will be perplexed by the abrupt reversals and inconsistencies in the behavior of officers who were prominent in the conspiracies of the period. A brief biographical sketch of these officers shows that institutional concerns overshadowed commitment to democracy or any particular ideology. One example is Air Force Captain Wilfrido Omaña, who is considered to be one of the outstanding martyrs in the struggle for democracy. Both before and after the abortive uprising at Boca del Río in September 1952, Omaña worked closely with top AD clandestine leaders in an attempt to foment opposition to Pérez Jiménez in the armed forces. Previously, however, Omaña had participated in a military conspiracy against the AD government in 1947 in Barcelona that served as a prelude to the November 1948 coup, and thus he cannot be fitted into the mold of the steadfast fighter for democracy. Among dozens of other examples is that of Colonel Juan Moncada Vidal (interviewed by Blanco Muñoz), who was more perejimenista than Pérez Jiménez. In the early years of the military dictatorship, Moneada attempted to remove the more civilian-minded President Carlos Delgado Chalbaud in order to allow Pérez Jimenez to assume absolute power. Following the events of 1958, Moneada participated in several military revolts that were branded as right-wing, only to join shortly thereafter the Castroite guerrilla group Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN). For a discussion of the institutional concerns of the military, see Burggraaff, The Venezuelan Armed Forces, pp. 90, 150, 196–97; Gene E. Bigler, “The Armed Forces and Patterns of Civil-Military Relations,” in Venezuela: The Democratic Experience, edited by John D. Martz and David J. Myers (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1977), p. 125; and Edwin Lieuwen, Venezuela (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 88.

9. Domingo Alberto Rangel, Los mercaderos del voto: estudio de un sistema (Valencia: Vadell Hermanos, 1973), p. 110.

10. See also Edito José Ramírez R., El 18 de octubre y la problemática venezolana actual, 1945–1979 (Caracas: Avila Arte, 1981), pp. 245–49.

11. J. Nef, “The Revolution That Never Was: Perspectives on Democracy, Socialism, and Reaction in Chile,” in LARR 18, no. 1 (1983):240–41.

12. Habló el general, interview by Agustín Blanco Muñoz (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1983), p. 136.

13. Rómulo Betancourt, Rómulo Betancourt: memoria del último destierro (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1982), pp. 133–34; Steve Ellner, Los partidos políticos y su disputa por el control del movimiento sindical en Venezuela, 1936–1948 (Caracas: Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, 1980), p. 116.

14. Ellner, “Leonardo Ruiz Pineda: Acción Democrática's guerrillero for Liberty,” in Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 22, no. 3 (August 1980):389–91.

15. Fuenmayor recognized that the AD's clandestine leaders represented a “leftist” tendency in the party and that they tried to encourage common AD-PCV activities in the students' and workers' movements. Nevertheless, he opposed PCV-AD unity on the grounds that the AD underground leaders failed to speak out against Betancourt's anti-Communist pronouncements. Fuenmayor, “Carta abierta a todos los militantes del Partido,” (Caracas, mimeo, July 1950); Fuenmayor, interview, Caracas, 7 June 1983.

16. Boletín Seminal (PCV), no. 20, 2 July 1951, p. 1; Pompeyo Márquez, “El 23 de enero de 1958: la culminación de un proceso,” in Enero 23 de 1958: reconquista de la libertad (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1982), p. 361; “Venezuela democrática,” May 1955, p. 12, in Prensa de los venezolanos en el exilio, México, 1955–1957: Venezuela democrática (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1983).

17. Alexander states that Communist publications, unlike those of the AD, “circulated comparatively freely” during the period. Robert Alexander, The Venezuelan Democratic Revolution: A Profile of the Regime of Rómulo Betancourt (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1964), p. 77; Robert Alexander, Rómulo Betancourt and the Transformation of Venezuela (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1982), pp. 345–46, 419.

18. Betancourt, Rómulo Betancourt, pp. 219–20.

19. Andrés Eloy Blanco, “Carta sin censura,” in Cuba: patria del exilio venezolano (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1982), pp. 155–56.

20. Rangel also makes this point in Los mercaderos del voto, p. 43.

21. Pedro Estrada habló, interview by Agustín Blanco Muñoz (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1983), pp. 122, 151, 167, and 251; Braulio Barreto, Confesiones de un esbirro (Caracas: Editorial Caracas 2.000, 1982), pp. 174–77; David Estellar, Weekend en las guerrillas: memorias de un combatiente en dos épocas críticas de nuestra historia—el 23 de enero y las guerrillas (Caracas: Editorial Domingo Fuentes, 1983), pp. 31–32. Catalá attempts to refute Estrada's remarks in Pedro Estrada y sus crímenes (Caracas: Editorial Centauro, 1983). The PCV's most valuable contribution during the latter part of the resistance period was to promote unity among the opposition parties, which resulted in the formation of the Junta Patriótica. Alexander differs from García Camacho (p. 225) in giving the AD major credit for initiating the unity approach that prevailed after 1954 (Rómulo Betancourt, p. 393).

22. For different versions of the circumstances surrounding Ruiz Pineda's assassination, see Charles D. Ameringer, “Leonardo Ruiz Pineda: Leader of the Venezuelan Resistance, 1949–1952,” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 21, no. 2 (1979):227-28; Cuando mataron a Ruiz Pineda, interviews by Guido Acuña (Caracas: Ediciones Rafael Arévalo González, 1977); José Vicente Abreu, “Leonardo, símbolo real del martirologio,” in Hombres y verdugos (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1982), pp. 33–46.

23. Younger COPEI leaders such as future President Luis Herrera Campíns, who participated in the university struggle of 1951–52, were exiled, and the party's National Youth Secretary Hilarión Cardozo was later jailed for four years. See José Rodríguez Iturbe, “Crónica de la década militar (II),” in Nueva política 37–40 (June 1981): 150; and Moisés Moleiro, El partido del pueblo: crónica de un fraude (Valencia, Ven.: Vadell Hermanos, 1979), p. 164.

24. Barreto, Confesiones de un esbirro, pp. 162–63; Jorge Dáger, Testigo de excepción: en las trincheras de la resistencia, 1948–1955 (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1979), p. 206; and Diego Salazar, Los últimos días de Pérez Jiménez (Caracas: Editorial Ruptura, 1979), pp. 195–96.

25. Fania Petzoldt and Jacinta Bevilacqua, Nosotras también nos jugamos la vida: testimonios de la mujer venezolana en la lucha clandestina, 1948–1958 (Caracas: Editorial Ateneo de Caracas, 1979).

26. Pérez Jiménez also attempted to justify the policies of his government in two recently published interviews: Pérez Jiménez se confiesa, interview by Joaquín Soler Serrano (Zaragoza: Editorial Dronte, 1983), pp. 81–91; Habló el general, interview by Blanco Muñoz. Giving these interviews marked a reversal of Pérez Jiménez's previous refusal to face the press. Blanco Muñoz (himself a leftist professor at the Central University) came under heavy attack for his failure to formulate provocative questions and for allowing Pérez Jiménez to present his viewpoint unchallenged (a similar criticism was leveled at his interview of Pedro Estrada). Catalá attempts to refute these accounts in his compilation Pérez Jiménez, el delincuente y sus delitos (Caracas: Ediciones Centauro, 1983). See also Catalá's compilation entitled Pedro Estrada y sus crímenes.

27. Martz, Acción Democrática, pp. 91–92; Alexander, The Venezuelan Democratic Revolution, pp. 45, 212; Hector Malavé Mata, Formación histórica del antidesarrollo de Venezuela, 2nd ed. (Bogotá: Editorial La Oveja Negra, 1980), p. 239; Domingo Alberto Rangel, Revolución de las fantasías (Caracas: Editorial OFIDI, 1966), pp. 33–36; and Salvador de la Plaza, Estructuras de integración nacional (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1973).

28. Blanco Muñoz, La lucha armada: hablan cinco jefes, pp. 41, 83, 176, 334–35; Blanco Muñoz, La lucha armada: la izquierda revolucionaria, pp. 183–84, 274–75; Blanco Muñoz, La lucha armada: hablan seis comandantes (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1981), p. 181.