Introduction

The death penalty's resurgence in the waning days of the Trump administration (Reference LiptakLiptak, 2021)—and the possible reinvigorating effect of those executions on state practices (e.g., Reference CastleCastle, 2021)—heightens the need to understand decision processes in these cases. Capital sentencing is an unusual and fraught area of jury decisionmaking. Jurors in the United States are typically fact-finders, but when they decide whether to impose a death sentence, they make a fundamentally moral judgment: determining what punishment a defendant deserves. Jurors are instructed to consider two types of evidence: “aggravating” factors that support a death sentence versus “mitigating” factors that support a sentence of less than death, for example, by contextualizing the defendant and the crime.

Empirical research raises stark concerns about how capital jurors decide on a sentence, including jurors' problematic reasoning about mitigation. Existing research indicates jurors may minimize or misunderstand mitigating factors (e.g., Reference Bentele and BowersBentele & Bowers, 2001; Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998); treat some mitigating factors as aggravating (e.g., Reference Stevenson, Bottoms and DiamondStevenson et al., 2010); and, according to some, hold to ideologies hostile to contextualizing evidence (termed “hegemonic individualism”; Reference Dunn and KaplanDunn & Kaplan, 2009; Reference KleinstuberKleinstuber, 2013). Indeed, understanding context and crediting explanations rather than dismissing them as mere “excuses” may be particularly challenging for capital jurors. Only those willing to impose the death penalty may serve as capital jurors, and this group tends to be more likely than a more representative sample to minimize and even reject mitigation (e.g., Reference Butler and MoranButler & Moran, 2002).

Our knowledge about deliberating jurors' treatment of mitigation, however, remains incomplete. Existing research uses indirect means—interviews, archival verdict data, and mock-jury studies—to understand jury deliberations. This article instead uses a novel and unique dataset of mitigating factors from actual capital jury verdict forms. In the federal system, verdict forms “enumerate” mitigation, presenting to the jury individual mitigating factors for a vote. Significantly, many of these forms permit juries to document their own mitigating factors during deliberations, an addition we call “write-ins.” Through write-ins, and other votes on mitigation, the jury “speaks” publicly about its views of mitigation.

These data cannot tell us whether jurors perform ably or poorly in deciding about death, a task, by most accounts, that no judge or jury can do fairly (see, e.g., Reference HaneyHaney, 2005). But write-ins and other verdict-form data usefully address two narrower aims. First, they offer an unfiltered gauge of real jurors' attention to mitigation during deliberation, which descriptively adds to scholarship about jurors' treatment of mitigating evidence. Second, these data grant a rare opportunity to observe what considerations jurors appear to regard as “focal” (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier et al., 1998; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth, 2000) as they consider reasons to spare a defendant, theoretical factors more typically studied among sentencing judges.Footnote 1 This allows us to examine whether and how juries bring an independent perspective to mitigation.

Mitigation in Capital Cases

Capital cases have two phases: the guilt/innocence phase, where the jury decides whether the defendant is guilty of capital murder, and the penalty phase, where the jury decides the sentence (Gregg v. Georgia, 1976). If the jury finds the defendant guilty, that same body next hears evidence relevant to sentencing. The prosecution presents evidence to argue the defendant deserves the death penalty because, for example, heFootnote 2 will be dangerous in the future or the murder was particularly heinous. The defense presents evidence and witnesses to mitigate the defendant's moral culpability. Common mitigators emphasize the defendant's lesser role in the crime, stressors weighing on him around the time of the crime, or that his actions reflect the effects of an abusive childhood or a mental disorder. Mitigation may attempt to humanize the defendant through witnesses to his good qualities, that he is, for example, a good parent or can behave pro-socially, even heroically (American Bar Association, 2003).

Federal capital jurors decide these questions in a more structured way than most state jurors. The federal verdict forms first ask jurors to vote on the defendant's eligibility for a death sentence (e.g., over 18 at the time of the crime and had a requisite mental state of, e.g., intent to kill or create a grave risk of death). If they agree, the form then instructs them to vote on the aggravating factors established in the governing statute (e.g., the crime was heinous and cruel or involved substantial planning and premeditation; see 18 U.S. Code § 3592). If the jury does not unanimously agree that the Government proved at least one of the statutory aggravators beyond a reasonable doubt, its deliberations end, and the defendant is sentenced by default to life in prison without the possibility of parole. If they do unanimously agree, they may be asked to vote on “nonstatutory” aggravators (e.g., whether the defendant is a future danger), which they again must unanimously decide the Government has proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

The verdict form then asks jurors to vote on mitigating factors, that is, specific reasons to spare the defendant. During the sentencing hearing, the defense generally offers evidence, through testimony from experts or laypeople who know the defendant, aimed at reducing a defendant's “moral culpability” (Penry v. Lynaugh, 1989) and blameworthiness. Mitigating factors have a lower standard of proof (“preponderance of the evidence,” instead of “beyond a reasonable doubt”); jurors do not have to be unanimous about the existence of any mitigator; and each juror can independently weigh the strength of the prosecution's case for death in light of the reasons to spare the defendant's life. Life without parole and death sentences both require unanimous decisions. If the jury cannot agree on a sentence, the defendant is sentenced by default to life without parole.

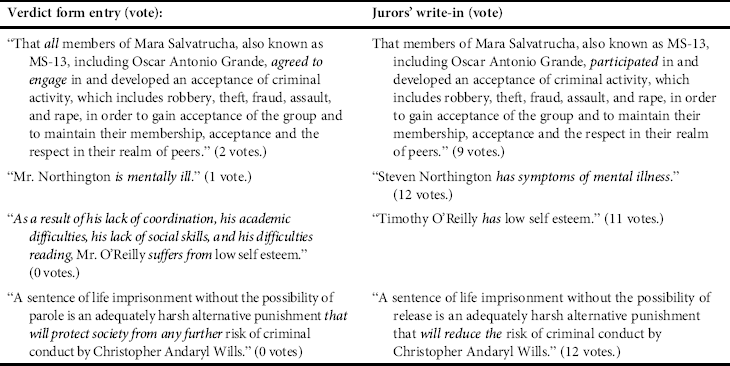

These mitigators are listed on federal verdict forms, typically with a space next to each to record how many jurors endorsed that factor. Enumerating and “pinpointing” material from the sentencing phase can improve mitigation comprehension (Reference Smith and HaneySmith & Haney, 2011), suggesting federal verdict forms may be superior to state court verdict forms, which do not typically provide this same level of detail and can sometimes provide little guidance on mitigation (e.g., failing to define it; Reference Smith and HaneySmith & Haney, 2011). Many state forms do not enumerate at all. Nevada and North Carolina enumerate but ask for only “yes” and “no” votes (see, e.g., Reference Jennings, Richards, Smith, Bjerregaard and FogelJennings et al., 2014), eliding detail about how much support each factor enjoyed (i.e., a “no” means zero votes, but a “yes” is any number between one and twelve). Few states permit the jury to write-in its own mitigators. (As we describe in our Discussion, New York State had forms that resembled federal ones in offering write-ins and enumerating mitigation but conducted few capital trials.) Figure 1 features a written-in factor from our dataset and two enumerated mitigators.

Figure 1. Sample write-in (from United States v. Aguilar, 2007)

Through write-ins, juries may elaborate on topics already presented to them or describe factors not discussed anywhere else on the form. This latitude is critical because mitigators are otherwise constrained by what defendants are allowed to argue to the jury or place on the verdict form (see Reference Rountree and RoseRountree & Rose, 2021 for some legal restrictions). Although modern death penalty law permits defendants to ask jurors to consider a wide range of evidence in support of a life sentence (Tennard v. Dretke, 2004), only evidence regarding the “character and record of the individual offender and the circumstances of the particular offense” (Lockett v. Ohio, 1978, 601) will be consistently admitted. States and federal circuits continue to differ on what they deem to be relevant to mitigation beyond the Lockett factors (Reference Rountree and RoseRountree & Rose, 2021). Write-ins therefore permit the jury to provide their own reasons the defendant deserves a life sentence.

Empirical Studies of Mitigation

Rhetorically, mitigation is challenging. The defense must disrupt the “crime master narrative” (unrepentant, psychologically “warped” individuals who prey on a constantly at-risk public; Reference HaneyHaney, 2008) and explain the defendant's actions without seeking to excuse or minimize the crime. The empirical profile of jurors, almost uniformly based on decisions or practices in state cases, presents an unflattering view of jurors' handling of mitigation, suggesting they are confused by, hostile to, or generally uninterested in mitigation. Surveys and experimental studies involving former and prospective jurors reveal a misunderstanding of the law of mitigation (see, e.g., Reference DiamondDiamond, 1993; Reference Eisenberg and WellsEisenberg & Wells, 1993; Reference Lynch and HaneyLynch & Haney, 2000), with some mitigators, including substance abuse and a history of child abuse, generating particular confusion or hostility. Mock jurors have construed these as aggravating, that is, that defendants have a weak character or, with an abuse history, a disposition toward violence (Reference Lynch and HaneyLynch & Haney, 2009; Reference Stevenson, Bottoms and DiamondStevenson et al., 2010). The Capital Jury Project (CJP) conducted post-trial interviews of subsets of jurors in capital cases and found that 62% did not view child abuse as mitigating; some said a drug abuse history made them more likely to sentence the person to death (Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998).

Other work suggests that mitigation is not much on jurors' minds. Reference TrahanTrahan (2011) identified qualitative remarks about mitigation in only 76 of 913 CJP interviews (see also Reference KleinstuberKleinstuber, 2013). Likewise, although quantitative analysis of the CJP and other data finds that the number of mitigators endorsed on a form predicts sentences (Reference Devine and KellyDevine & Kelly, 2015; Reference Kremling, Smith, Cochran, Bjerregaard and FogelKremling et al., 2007), the number or type of aggravators endorsed can be stronger predictors (Reference Kremling, Smith, Cochran, Bjerregaard and FogelKremling et al., 2007).

One significant explanation of jurors' attitudes is “death qualification,” a procedure to ensure that only those willing to consider a death sentence serve on capital juries (Wainwright v. Witt, 1985; Witherspoon v. Illinois, 1968). This selection process tends to yield a jury less open to mitigation (Reference Butler and MoranButler & Moran, 2002; Reference HaneyHaney, 2005; Reference Luginbuhl and MiddendorfLuginbuhl & Middendorf, 1988). In contrast to mitigation, prosecutors' aggravation narratives will tend to focus on personal responsibility and free will. This aligns with most Americans' intuitions. Americans tend to look for and make attributions about behavior by assuming that actions correspond to and reflect free choice and controllable aspects of one's disposition (see, e.g., Reference HaneyHaney, 2008; Reference HeinrichHeinrich, 2020). This makes contextual, situational aspects of a defendant's life or his crime more difficult for jurors—particularly the more conservative subsample of death-qualified jurors—to both generate and endorse. All these factors contribute to some scholars' view that capital jurors adhere to “hegemonic individualism,” an ideology that accepts individualistic explanations of behavior, including criminal behavior, uncritically and rejects accounts that challenge this viewpoint (Reference KleinstuberKleinstuber, 2013; see also Reference Dunn and KaplanDunn & Kaplan, 2009).

If jurors dismiss mitigation, any invitation to add their own reasons to spare a defendant may be unavailing. However, to date the opportunity to observe whether and what jurors may add to the case for mitigation during deliberation has not been feasible. The specificity of write-ins—a section at the end of the mitigation portion of verdict forms, typically available only in federal cases—renders them an unlikely topic for a mock-jury study. Further, post-deliberation interviews with a subset of jurors in state cases may not capture this aspect of decisionmaking. Given that jurors can assess mitigation independently of other jurors, and without the structure of a verdict sheet that formalizes additional thoughts on mitigation, the subset of people interviewed may not recall other jurors' views or explain what aspects of mitigation were “new” compared to what was presented to them.

The recorded detail in federal verdict forms is invaluable as it makes visible jurors' deliberative thinking, allowing the development of a broad outline of jurors' treatment of mitigation. How often do juries write in mitigators? Do juries raise their own concerns, suggesting independent reasoning, or are they in dialog only with the mitigators printed on the form? Do vote totals suggest that write-ins represent the idiosyncratic views of only a few jurors, or do most jurors agree that a given factor is mitigating? Answers to these questions are possible only through verdict form data.

Potential correlates

In addition to the frequency, novelty, and support of write-ins, verdict forms offer information on their possible correlates. Because verdict forms enumerate aggravators and mitigators, we can ask whether write-ins track other indicators of support of mitigation and whether they relate to views of aggravating factors. Specifically, we would expect that written-in factors are more likely to appear on forms that also have higher vote totals for enumerated mitigators and lower totals for enumerated aggravators. If our expectation is correct, write-ins may signal leniency on the jury's part and would be more likely to appear in cases that are stronger on mitigation and weaker on aggravation. Note that this outcome is not inevitable: conceivably jurors might compensate for attorneys' inadequate mitigation cases by developing their own reasons to spare the defendant.

Race and mitigation

Given longstanding associations between race and the death penalty, we would expect a relationship between race and write-ins. With some exceptions (e.g., Reference Berk, Li and HickmanBerk et al., 2005; Reference Devine and KellyDevine & Kelly, 2015), most research suggests a jury's capital sentencing decision is racialized, compounding disparities at the charging and pleading stages (e.g., Reference Baldus, Woodworth and PulaskiBaldus et al., 1990). Some studies find, for example, that death sentences are particularly likely where a Black defendant has killed a White victim (Reference Baldus, Woodworth and PulaskiBaldus et al., 1990; Reference Bowers, Steiner and SandysBowers et al., 2001; Reference HaneyHaney, 2005; Reference Lynch and HaneyLynch & Haney, 2000; Reference Paternoster and BramePaternoster & Brame, 2008) or the victim is female (Reference Holcomb, Williams and DemuthHolcomb et al., 2004; Reference Williams, Demuth and HolcombWilliams et al., 2007).

According to CJP interview data, these racialized patterns generalize to receptivity of mitigation. Interviewees expressed more support for mitigation when defendants and jurors were of the same race and the victim was not, for example, where White jurors discuss a White defendant who killed a non-White victim (Reference BrewerBrewer, 2004). In capital cases, on which White jurors are more likely to serve (e.g., Reference Baldus, Woodworth, Zuckerman, Weiner and BroffittBaldus et al., 2001), this research suggests the jury would credit explanations of non-White defendants' individual blameworthiness (i.e., aggravators) over mitigating evidence contextualizing their actions, making the addition of write-ins less likely when the defendant is non-White. Further, jurors may be less willing to generate additional mitigation for defendants who have murdered a White victim or a female victim.

Considering the call to examine race effects in light of other significant case facts (Reference Berk, Li and HickmanBerk et al., 2005; Reference Devine and KellyDevine & Kelly, 2015; Reference Jennings, Richards, Smith, Bjerregaard and FogelJennings et al., 2014), we explore questions of race and gender outcomes using both a bivariate and multivariate approach, controlling for variables available to us such as endorsement rates for aggravating factors and the presence of significant aggravators (e.g., future dangerousness; Reference Blume, Garvey and JohnsonBlume et al., 2000), as well as overall support for mitigation. If members of one group are more or less likely to receive written-ins, we would be able to determine if that result tracks any racialized/gendered patterns in a defendant's broader case for mitigation.

The Content of Write-Ins: Sentencing Theory and Juries

The above review points to the descriptive value of examining write-ins and some of their correlates. It does not, however, suggest what write-ins might say. For this, we turn to theories of sentencing typically applied to judges' rather than jurors' sentencing decisions. As Reference UlmerUlmer (2012) notes, sentencing involves “interpretive processes” (p. 8), influenced by an interaction between a judge—the typical sentencer in a noncapital case—and a defendant, within the context of a courtroom working group (e.g., Reference Eisenstein, Flemming and NardulliEisenstein et al., 1988), as well as within a given legal regime and socio-cultural context (see Reference Kramer and UlmerKramer & Ulmer, 2009). One particularly influential theory of decisionmaking in this context of high uncertainty indicates that judges are guided by specific “focal concerns.” Under Focal Concerns Theory (FCT; Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier et al., 1998), judges' sentences combine traditional punishment considerations (namely, retribution and deterrence/incapacitation), and potentially more idiosyncratic/case-specific factors that reflect characteristics of the defendant, the punishment regime under which they operate, and the concerns generated through judges' courtroom culture/community. In theory, these assessments contribute to demographic differences in sentences (Reference Steffensmeier, Kramer and StreifelSteffensmeier et al., 1993), although the precise mechanisms by which FCT can account for racial, gender, or age disparities is subject to debate (see Reference LynchLynch, 2019). Although not every case raises all focal concerns in the same way, these concerns structure the challenging question of what sentence a defendant deserves.

A primary focal concern in sentencing is the defendant's blameworthiness, which reflects traditional attention to retributive concerns. Relevant here are the crime's seriousness as well as a defendant's prior criminal history, and leadership role in the crime. Whether the defendant has a background of victimization by parents or others, reduced mens rea, or was more of a follower than a leader in the crime can mitigate blameworthiness. In legal terms regarding mitigation, these implicate the “character and record of the individual offender and the circumstances of the particular offense” (Lockett v. Ohio, 1978, p. 601). A second focal concern involves future-based judgments of risk and protection of the community, which focuses on assessments of a defendant's future danger and recidivism, which resemble more classical incapacitation and deterrence (specific and general) concerns.

FCT supplements these more traditional retributive and deterrence concerns with what scholars term the “practical constraints and consequences” of sentences (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier et al., 1998), also called “organizational constraints and practical consequences” (Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth, 2000). These include considerations such as a sentence's impact on the defendant and those associated with the defendant (the defendant's children, the defendant's ability to survive prison, costs to corrections), as well as the impact on the judge's career and working relationships with others in the “court community” (Reference Eisenstein, Flemming and NardulliEisenstein et al., 1988; see also Reference Kramer and UlmerKramer & Ulmer, 2009; Reference UlmerUlmer, 1997). The practical constraints and consequences concern offers a potential explanation for observed sentencing disparities between men and women, as judges have reported a belief that children suffer more when their mother is imprisoned than when their father is (e.g., Reference DalyDaly, 1987; Reference Steffensmeier, Kramer and StreifelSteffensmeier et al., 1993).

The applicability of FCT to jurors who sentence is not well understood. Jennings and colleagues argue that blameworthiness and community safety are the “focal concerns most relevant in capital juror decisionmaking” (2014, p. 385). Empirical research supports these two classic punishment concerns. Psychological and sociological studies of lay theories of punishment generally find that blameworthiness and retribution concerns dominate punishment judgments (e.g., Reference Carlsmith, Darley and RobinsonCarlsmith et al., 2002; Reference Rossi and BerkRossi & Berk, 1997). In CJP data, large pluralities (>40%) of interviewees said that factors such as cognitive deficits, a history of mental illness, and being under 18 at the time of the offense made them less likely to vote for death (Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998). Thus, we would expect that any write-ins that jurors offer would tend to reflect these types of blameworthiness concerns.

Community safety concerns are also likely relevant to jurors. CJP scholars argue future dangerousness is “always at issue” in capital jurors' minds, whether or not jurors are explicitly asked to consider this factor (Reference Blume, Garvey and JohnsonBlume et al., 2000; see also Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998). Nonetheless, it is not clear that these concerns will arise as part of mitigation. Defense attorneys sometimes use mitigation to counter aggravation and argue that the defendant is not likely to be dangerous (e.g., due to his older age and/or infirmity or because he will not pose a threat in prison); but whether jurors independently concern themselves with this topic is not clear. At the same time, if future dangerousness is “always at issue” for jurors, endorsement of that aggravating factor may dominate their thinking. In this case, write-ins of any type—that is, additional reasons to spare a defendant—may be less likely when jurors have also endorsed future danger as an aggravating factor.

Finally, because FCT blends both traditional retributive and deterrence concerns with a more novel concern for “practical constraints and consequences,” and because this factor is less clearly subsumed under the background and character of the defendant, we are particularly interested in whether jurors' write-ins reflect this focal concern. Finding that jurors, like judges, attend to sentence consequences would be new and broaden our understanding of the applicability of the FCT framework to juror sentencing.

Applying this construct to jurors is not straightforward. Some aspects of judges' practical constraints are either irrelevant for jurors or likely unobservable. As nonrepeat-players, jurors have neither “career concerns” nor “courtroom community” relationships. Reference Jennings, Richards, Smith, Bjerregaard and FogelJennings et al. (2014, p. 385) suggest jurors may be concerned with their broader community's “norms/expectations” about sentencing, but jurors are unlikely to share this concern publicly. Jurors are not supposed to concern themselves with what others may say about their verdicts; regardless of whether they do so, CJP jurors who have sentenced a defendant to death overwhelmingly say they gave no consideration to community sentiment (see Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998, p. 1568).

At the same time, other meanings of “practical constraints and consequences” have emerged in prior work but not been labeled in those terms. In recalling which witnesses were crucial in decisionmaking, one CJP participant explained the following:

I think that was the most mitigating thing that would lead us away from the death penalty—just how it was devastating to [the defendant's family]. That basically, having him put to death is just going to create more victims (Reference SundbySundby, 1997, p. 1155).

This anecdote focuses attention on a more literal meaning of “practical consequences”—that is, the specific and expected consequences of a given sentence. To date it has been challenging to observe juror attention to even this narrower meaning of the third focal concern. For example, Paternoster and colleagues coded case transcripts, including whether the defendant has a spouse and/or family, but it is not clear how often jurors endorsed it as mitigating (see review of results in Reference Paternoster and BramePaternoster & Brame, 2008). According to CJP data, of those who said the factor, “Defendant has a loving family,” was present in their case, only 26.7% said that it made them slightly or much more likely to vote for life (Reference GarveyGarvey, 1998). Still, in both these studies, what jurors make of the presence of a family is not clear. Perhaps it humanizes the defendant and supports the idea that the crime was an aberration, but this is different from what FCT posits, namely, the sentencer's concern for how the sentence will affect defendant's family (e.g., a sentence of death means that a defendant's child loses a parent). Courts are divided with respect to the admissibility of evidence regarding the harm of execution to the defendant's family (Reference Rountree and RoseRountree & Rose, 2021). This makes this concern a particularly fruitful one to consider among independent jurors.

Ultimately, write-ins enable us to observe more directly themes that emerge in jurors' deliberations about mitigation and whether these themes correspond to FCT. This includes a better understanding of any “practical constraints and consequences” jurors may consider during mitigation, a factor that may not reliably appear as an enumerated item on the verdict form (Reference Rountree and RoseRountree & Rose, 2021). To directly see what “focal” mitigation issues jurors consider during deliberation, jurors need to speak for themselves, something that write-ins uniquely permit. Although evidence presented during the punishment phase shapes the content of the printed mitigation on the form, we can code whether the written-in material differs substantially from what is presented (i.e., is “new”). Analysis of write-ins also permits us to see whether they express other concerns not fully captured in the existing FCT framework.

The Present Study

We use information about mitigation from federal verdict forms, with particular attention to factors that jurors write in, to examine how often jurors offer additional mitigators through the write-in portion of federal verdict forms; whether write-ins correlate with the perceived strength (or weakness) of the broader case for mitigation and aggravation; whether write-ins, like other aspects of capital sentencing, are patterned by the race of the defendant or the race/gender of the victim; and the extent to which any additional mitigators jurors offer on verdict forms align with FCT components of blameworthiness, safety, practical concerns and consequences, and/or something else. As we note below, in assessing the content of what jurors offer on the forms, we specifically consider whether write-ins build upon themes already on the verdict form, or whether they add their own ideas and “concerns” to the sheet. To examine these questions, we reviewed over 200 federal capital jury forms from the website of the Federal Death Penalty Resource Counsel (FDPRC), coded all mitigators and aggravators, and, after identifying any written-in mitigators, coded their content.

Data and Method

The FDPRC has uploaded to its website nearly allFootnote 3 of the publicly available sentencing verdict forms in federal death penalty trials held from 1991 to 2018 (Penalty Phase Verdict Forms, 2017). We downloaded 223 files, covering 226 defendants (in three cases, a single file presented juries' assessment of two different defendants); the unit of analysis is a jury's assessment of a single defendant, which we refer to as a “form.” We eliminated 21 forms because the form(s): was not a sentencing form (n = 1); stemmed from a bench trial (n = 2), lacked mitigators (n = 3); contained no mitigation votes because the jury was not unanimous on a statutory aggravator (n = 9); did not reveal the vote tally (e.g., the form listed mitigators but did not provide lines for votes, or instructions permitted jurors to not reveal their votes and they did not; n = 6). The resulting database consisted of 205 verdict forms from 171 unique juries (i.e., some juries judged multiple defendants).

As detailed above, the verdict forms followed a common structure, first asking the jurors to decide whether the defendant was eligible for the death penalty and then statutory and nonstatutory aggravating factors. Next came the section on mitigation, with the space for a vote on each factor, typically (for 93% of forms) requiring a numeric vote. Across all forms and counts, jurors voted on 7686 mitigators. Considering only a single count in each case, there were 4913 unique mitigating factors listed on the forms.

At the end of the mitigation section, most forms provided juries with opportunities to write-in their own mitigating factors. We define “opportunity” as blank lines or space appearing in the form with instructions for write-ins; 174 forms from 147 unique juries (85% of the total forms, 86% of juries) gave jurors such an opportunity. No jury wrote in mitigation without being presented with the opportunity to do so. The forms without an opportunity tended to come from the older set of cases in the dataset (71% of the no-opportunity cases came before 2005, compared to 42% of forms with write-in opportunities; all forms after 2008 included a write-in opportunity). Fully 32% of the no-opportunity cases were from the Central District of California (n = 5) and the Western District of Virginia (n = 5), also suggesting differences in regional practice. (No statistical difference in average votes, mitigation endorsement, or death sentences existed between those with and without a write-in opportunity). Notably, in seven of the no-opportunity forms, there was a line of mitigation that said, commonly, “Other mitigating factor(s) found by at least one juror” (precise wording varied), and this garnered zero votes, suggesting these juries likely would not have written in a factor, even given an opportunity. Below we report any differences, where relevant, when we use different configurations of the dataset: that is, results for all 205 forms, for all 171 juries, for the 174 forms with write-in opportunities, or the 181 forms with either opportunities or zero votes for “other.”

Procedure

Trained coders read the forms and classified the content of each enumerated mitigating factor. This process identified broad domains of mitigation—specifically childhood/background factors, mental state factors, and other contextualizing factors—as well as whether the form included a write-in. Tests of inter-rater reliability for this assessment were excellent (kappa = 0.95–0.96 across tests). The authors also independently checked all verdict forms to ensure that we did not miss any write-in factors. Once we identified and transcribed all write-ins, the two authors independently read forms from the write-in cases to determine (a) the themes underlying the write-in; and (b) whether or not the content of the write-in offered new information compared to what already appeared on the form.

Write-in themes

A plurality of the forms (n = 81, 40%) used Lockett-type language and instructed jurors that write-ins should concern the defendant's “background and character” or “background, character, or other circumstances of the offense” (see, e.g., the instruction in Figure 1), all of which appear to narrow the potential mitigator's focus to concerns relevant to blameworthiness and moral culpability. Based on this, and research suggesting that retribution is a primary concern among laypeople (e.g., Reference Carlsmith, Darley and RobinsonCarlsmith et al., 2002), we approached write-ins by first identifying a basic distinction between issues of moral blameworthiness/culpability versus all other factors. Blameworthiness included comments on the defendant's mental state, prior contextualizing experiences (e.g., child abuse, coming from an at-risk neighborhood), as well as positive comments about the defendant's character. We then examined all factors not linked to blameworthiness and considered what concerns they reflected, which we describe in Results. Our coding produced excellent reliability: 90% raw agreement and a kappa of 0.83. We reviewed each disagreement to finalize codes.

Newness of write-ins

We were interested whether jurors' write-ins demonstrated independence (“newness”) from the factors enumerated on the form. If a write-in elaborated upon an issue already on the form, the factor was not “new.” For example, in one case, the verdict form asked jurors whether they found that, “[The defendant's father] was incarcerated in federal prison for the majority of Patrick's childhood, leaving Patrick without a positive role model” and whether “[The defendant's father] helped ‘train’ fifteen year-old Patrick as a drug dealer when [the father] got out of prison.” This jury wrote in that “[The defendant's father] was unable to provide the nurturing and protection of a father.” In this case, the write-in was considered “different but related” to the verdict form factors (i.e., not new) because it elaborated upon the idea already on the form: the defendant's father was largely absent, and when present, was a poor role model. If no such link existed, we deemed the write-in “new.” As we will show, newness is relative only to other mitigators on the verdict forms and is not “extrajudicial”; most entries reflected evidence juries likely heard or were predictable impressions formed from the trial. (Conceivably, attorneys broadly referenced these issues in their case for mitigation but did not or were not allowed to put them on the form; without access to trial transcripts, we cannot know.) Coding produced high raw agreement (80%) and good reliability (kappa = 0.60). We again reviewed each disagreement to produce a final code.

Race of defendant/victims

FDPRC shared an Excel file of the race/gender of the defendant and of some victims, and a research assistant confirmed its accuracy wherever possible through press reports and other searchable online databases. For victims, the database listed only a maximum of three victims, even if the crime had more. For example, Dylann Roof murdered nine people at the Church of Emmanuel in South Carolina, but the database lists a Black Female, a Black Male and then a “+” sign to indicate additional victims. Further, all the mass terrorism/indiscriminate bombing cases (Oklahoma City, East African embassies, Moussaoui's 9/11 trial, and the Boston Marathon bombing) contain highly limited information on the race/gender of all victims. Thus, we have a valid indicator of which cases involved at least one White victim (1 = yes, 0 = no), at least one Black victim (1 = yes, 0 = no), and at least one female victim (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Consistent with most studies of capital punishment, Blacks are over-represented as defendants (50.7%). White and Black defendants in these cases were accused of predominantly intra-racial crimes: 88% of cases of White defendants included at least one White victim (just eight White-defendant cases involved a non-White victim), whereas 74% of cases with a Black defendant included at least one Black victim. Both patterns were highly significant (p < 0.0001). Defendant race and victim gender were not significantly associated (p < 0.27). Table 1 presents the frequency of race and gender characteristics across cases, together with other case measures.Footnote 4

Table 1. Case characteristics of Federal Capital Database

Note: N = 205 verdict forms.

a Most of this group is Latino (n = 28).

Other case measures

To examine how write-ins may relate to other form outcomes, particularly mitigation decisions, we calculated what proportion of mitigating factors received nonzero votes, dividing all mitigators with nonzero votes by total mitigation presented on the form (percent mitigation endorsed). Taking advantage of the detailed federal forms, we also recorded the numerical vote for all mitigating factors.Footnote 5

Research assistants also counted the number of aggravators (statutory and nonstatutory) presented to the jury, as well as how many of those the jury unanimously endorsed as true. Reliability for these counts was very high (intraclass correlation = 0.99 across coders); the resulting variable (percent of aggravators endorsed) reflects the number endorsed divided by the number presented.Footnote 6 Because community safety is part of FCT and described as important to capital jurors (Reference Blume, Garvey and JohnsonBlume et al., 2000), we reviewed all forms to identify whether future dangerousness was one of the nonstatutory factors.Footnote 7 Likewise, although we do not attempt to predict sentence outcomes, Table 1 provides the distribution of sentences (unanimous on death, nonunanimous on life, or unanimous on LWOP).

Results

Frequency of write-ins

Jurors offered a total of 218 written-in mitigators, of which 149 were nonredundant across counts. Overall, 73 verdict forms contained write-ins, or 35.6% of all 205 forms, and fully 42% of the 174 forms that provided an opportunity to write in (40.3% if we include the seven no-opportunity cases that voted “0” for “other”). Write-ins came from 63 unique juries, that is, 36.8% of our 171 unique juries, and 42.9% of the 147 unique juries given an opportunity to write in mitigation.

When juries added write-ins, they frequently offered more than just one. Roughly half (n = 37) wrote in a single factor; the remaining ranged from 2 to 9, for an overall mean of 2.04 (SD = 1.59) unique write-ins per form (among those providing a write-in). In terms of jury support, the mean write-in vote was 7.27 (SD = 3.72), slightly above half the jury. Only 16.7% of the unique write-ins (n = 24) generated just one or two votes; a higher proportion, 27% (n = 39 instances), had votes of 11 or 12.

Newness

The majority of write-ins offered new material (i.e., not clearly linked to factors already printed on the form). We coded 85 (57.1% of the 149 unique entries) as new, 60 (40.3%) as linked to other issues on the form, and 4 (2.7%) as unclear (in either meaning or its link to another factor). We provide more information in the section on content/focal concerns. Ahead of that, we note an unexpected pattern among a subset of those that were not “new.” Of the 60 write-ins that we could link to issues already on the verdict form, we identified 11, across 7 unique cases, as “rewrites.” In these instances, jurors rewrote an existing factor, typically resulting in a higher vote than the enumerated version. Examples (with rewritten text placed in italics) include:

As these examples suggest, far from ignoring a mitigation claim, some juries attended carefully and independently enough to restate the defense's proffered factor to precisely convey the statement members would support: striking the term, “agreed to engage in,” a defendant “participated in” a gang's crimes, rendering his specific choices/mental state irrelevant; someone has symptoms of mental illness, rather than being definitively “mentally ill”; someone has low self-esteem, regardless of its causes or whether the defendant “suffers” from it; and future dangerousness is about risk, rather than certainty.

Predictors of write-ins on forms

Using results from juries that either had a write-in opportunity or listed a vote of “0” for “Other factors,” we examined write-in correlates. The proportion of cases with write-ins correlated with the social characteristics of the defendant and the victim but not in the ways we anticipated. Recall that 40.3% of these 181 forms produced one write-in. That proportion was significantly lower when the defendant in the case was White (25.9%, p < 0.05) and significantly higher when the defendant was other-race (61.8%, p < 0.01; Black defendants' proportion was 40.9%). This lower proportion among White defendants does not correspond to fewer mitigating factors on their forms. Although the number of mitigators enumerated on the form was highly variable for all groups, on average it was higher among White (51.85, SD = 78.18) compared to Black (30.73, SD = 31.75, p < 0.05) or other-race (32.27, SD = 28, p < 0.08) defendants. There were no race differences in the percentage of mitigators endorsed (72% for White and Black defendants, 75% for the other-race group), and average votes did not significantly differ (range: 5.44–5.82 across the groups).

When cases had at least one White victim or at least one Black victim, write-ins were not significantly more or less frequent (35.9% and 38.2%, respectively, n.s.); cases with at least one female victim were less likely to have a write-in than those without (31.3% vs. 47.5%, p < 0.05). (Again, there did not appear to be underlying differences in total mitigators presented or endorsed across these case differences.)

We found no evidence that jurors used write-ins to compensate for poor mitigation; instead, jurors' other votes on mitigators predicted the presence of write-ins. Forms with write-ins had a higher percentage of nonzero votes on mitigators (82% vs. 65%, p < 0.0001) and higher vote totals on other (non-write-in) mitigating factors (M = 6.50) compared to those without a write-in (M = 5.02, p < 0.001). The portion of the form devoted to aggravation also had a bivariate relationship with write-ins. Write-in forms had a lower percentage of the aggravating factors endorsed (M = 76.1%) compared to those that lacked a write-in (M = 90.1%, p < 0.0001); write-in forms were also less likely to have unanimous votes for future danger (31% vs. 73%, among juries presented with future danger, p < 0.0001). (Write-in and non-write-in forms did not differ on whether future danger appeared as an aggravator.)

Given these multiple bivariate associations with write-ins, including with respect to race, we ran a multivariate hierarchical logistic regression model in SAS (Proc GLIMMIX) to predict a write-in on a form (1 = present), with random intercepts nested within juries to account for the fact that some juries made decisions on more than one defendant. For ease of interpretation, we first standardized the percent of mitigators or aggravators endorsed. Table 2 contains all variables tested. Write-ins were less likely when jurors endorsed a greater percentage of aggravators, and they were somewhat more likely as endorsement for mitigation increased. Specifically, juries that were one standard deviation higher on percentage of aggravators endorsed were less likely to offer a write-in (OR = 0.56), whereas a one-standard deviation increase in the percentage of mitigation endorsed doubled the odds of offering a write-in (OR = 2.19), although this was just above conventional significance (p < 0.06). Net of these, more leniency as measured by higher average votes on non-write-in mitigators was not predictive. In addition, a focal concern specific to community safety (i.e., future dangerousness assessments) did not independently predict write-ins. Compared to other-race defendants, White defendants were about one-seventh as likely to receive a write-in (OR = 0.13). Although the presence of at least one female victim had a bivariate association with write-ins, that effect was not significant in the multivariate model.Footnote 8

Table 2. Hierarchical logistic regression results for likelihood of a write-in (n = 181 cases from 152 unique juries)a

a Excludes cases that did not offer an opportunity for a write-in, unless the jury voted 0 for the existence of “other” factors, in which case write-in was set to absent.

+p < 0.06, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

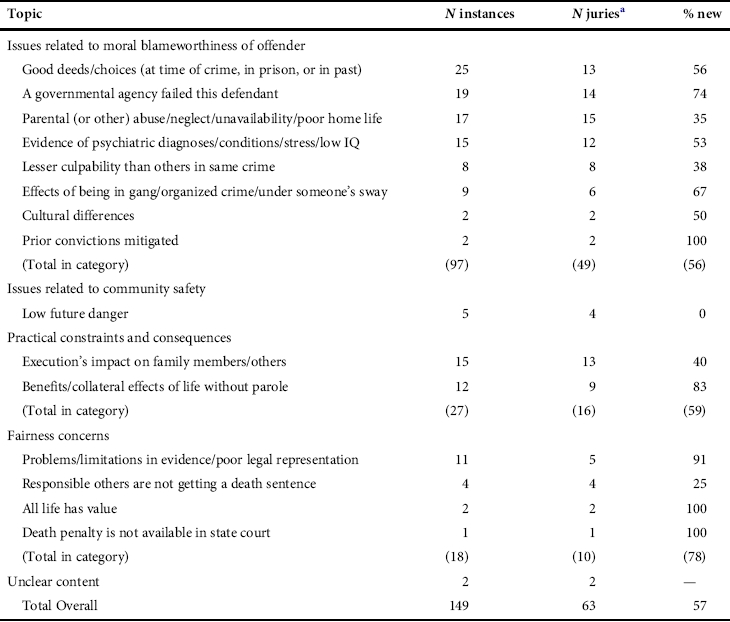

Write-in content: Focal concerns and fairness concerns

Table 3 describes results from our thematic coding, the frequency of each theme across write-ins and across unique juries, as well as the proportion of write-ins not linked to other mitigators on the form (“new”). In addition to the key focal concern of blameworthiness (which, as noted, verdict form instructions typically encourage jurors to focus on), we found evidence for some attention to community/future danger and the practical consequences of the sentence. We also identified another set of concerns that did not fit neatly into any of the three primary focal concerns constructs: the procedural fairness of the death penalty in this case.

Table 3. Prevalence of themes and newness coding among write-in mitigators

Note: Numbers in this column do not sum to the theme total or the “Total Overall” because half of juries offered more than one write-in/theme.

a Refers to unique juries to account for instances in which the same jury had write-ins for multiple defendants.

Blameworthiness

As Table 3 shows, the largest category of write-ins spoke to moral culpability and blameworthiness (n = 97 instances, or 65.1% of total), including issues of character, disadvantages, and a mitigated mental state. Among cases with write-ins, the vast majority of juries offered views on blameworthiness (n = 49 of 63 unique juries, 77.8%), which constituted about one-third (32.8%) of all juries that had the opportunity to write in a mitigator. More than half of these (56%) were coded as new.Footnote 9

Common were examples of good character, including participating in Bible study while in prison (two different juries), serving as a resource for family members (e.g., “Larry counsels his children about the danger of drugs”; in another, “The defendant has artistic talent and his family has benefited from his artistic expression”), acts of contrition/acceptance of proceedings (“Naeem Williams has asked for forgiveness from Talia Williams”; in another, “He showed great respect in court!”), or other examples of being kind or doing good (e.g., noting that the defendant had previously prevented an assault). A majority of these character concerns (56%) could not be linked to other mitigators on the form.

Another common sub-category was the defendant's disadvantaged background, although we distinguish between two sources that differed greatly on whether they were coded as “new” or not. The first were disadvantages stemming from the actions of parents or close others (n = 17 instances from 15 unique juries): “Billy Allen had no strong guiding parenting influence in the home”; “Dr. Moores testified that Tina Cooper told him in an interview that Billy D. Cooper's parents never told him that they love him”; “At a critical age, Kaboni Savage's father passed away and Gerald Thomas became a negative influence in his life.” These factors tended to echo existing mitigators; just 35% of comments regarding neglect or abuse were coded as new.

Additionally, multiple juries (n = 14) also pointed out instances in which specifically the government failed the defendant—and jurors typically used a version of the word “fail” in their write-in. This sub-category included the long-ago actions of various state agencies—for example, “…Failure of the State of Pennsylvania social and mental health services to effectively intervene in his childhood abuse and to treat or address his early antisocial behavior.” The justice system in particular—court, corrections, or law enforcement community—were also listed as having failed, for example, that a probation agency “failed to intervene in Billy's downward spiraling path” or that the court system “failed” the defendant “when psychological treatment was not forthcoming in 1997, when ordered by a judge.” Some failures were quite close in time to the crime and seemed to suggest contributory negligence (e.g., “Joey [the victim] died because the guards failed to do 30 minute rounds”’ “BOP [Bureau of Prisons] lack of consideration for his [defendant's] prior crimes for housing placement” in a case in which a defendant killed his cellmate). Among blameworthiness factors, government-specific actions were the most likely to be coded as “new” (74%).

Mental state issues were also common. Twelve different juries offered 15 write-ins regarding psychiatric diagnoses or cognitive impairments (e.g., low IQ). These issues were sometimes general (“Tello's mental incapacity/deficiencies played a role in his decisionmaking”) or suggested undiagnosed conditions (e.g., “Amesheo's violent actions in jail indicate possible emotional instability or an anger management disorder”). Jurors also noted stresses on defendants, including the loss of a parent, witnessing violence, financial and marital strain, or that the defendant “was given the impression that [the victim] was molesting his daughter.” Just over half (53%) of these mitigators were “new.”

In eight instances, jurors noted that the defendant's culpability was less than others. Two brothers, for example, were tried separately for killing a fellow prison inmate. Each jury noted that the nondefendant brother bore greater responsibility for different aspects of the offense: “Rudy played a lesser role [than William] in the desecration of the body of Joey,” whereas (for William) “The circumstances that led to Joey Estrella's death were influenced and/or instigated by Rudy Sablan.” Two different juries pointed out that another person “pulled the trigger” or “was the actual shooter,” and two others noted the defendant's “nonleadership role” in a criminal enterprise or crime. About one-third of these were new (38%).

Other comments regarding mental state noted the impact of organized crime or other people. Six juries gave nine examples related to gangs (e.g., the defendant was “Protecting his turf—like a soldier”; “Gang mentality and influence”) or powerful others (e.g., “Walter apparently looked to Tyrone Walker as his hero/mentor and was following along with him”; “[A lover's] presence, intimidation and corrupt influence on Mr. Wilks”). Because of its link to gangs, we include in this category three comments from two juries in which the jury placed some responsibility for the crime onto the victim who had a gang/syndicate association: for example, a slain witness to syndicate activity “put himself in harm's way” and another jury, writing for two defendants involved in MS-13, wrote: “The crime was against one of their own group who shared a common ideologic (sic) philosophy and understood the group's rules.” All these victim-blaming comments were coded as “new”; the overall theme of gang/other influences had a newness rate of 67%.

The remaining issues under the broader theme of blameworthiness all appeared on more than one unique jury, but were fairly idiosyncratic (and all but one were new). Two juries noted that the defendants were raised in different cultures (e.g., “Al-Owhali was raised in a completely different culture, society, and belief system”), and in two other instances, that the defendant's prior offenses were not as diagnostic as the Government argued: “Defendant's prior convictions were noncapital,” or were committed at a young age.

Community safety

As noted above, future dangerousness assessments did not predict whether jurors offered a write-in or not, net of other factors. Further, mitigation was not the area juries used to express many community safety concerns. Just four unique juries commented on why the defendant was unlikely to be violent in the future, with one noting, for two defendants, that they had “less tendency toward violence in prison because of age.” One stated that a defendant does not “pose a threat to society,” another wrote that life without parole “will reduce the risk of criminal conduct”; finally, one noted a recent psychological report finding low potential for harming others. Low future danger appeared elsewhere on all the forms, so none of these was new.

Practical consequences of a sentence

Write-ins provided clear evidence that some juries, like judges, care about the practical effects of sentences. Fully 13 separate juries offered their view of how a death sentence would affect the defendant's family and/or others (e.g., “Lashaun is the only biological parent alive for Christine, his daughter”; “Crystal Wills will be adversely affected due to the loss of all paternal contact if [defendant] is executed”), or (in separate cases) the defendant's sister, a grandmother, or a brother. Concerns were sometimes broader (“Future generations of the defendant's family will be negatively affected by the death of Ahn. They might see the government as the cause of that death”), and another talked about messages to terrorist communities (“Executing al-'Owhali could make him a martyr for al Qaeda's cause”). This same jury also stated that “Executing al-'Owhali may not necessarily alleviate the victims' or the victims' families' suffering,” an example of the absence of a practical effect. The last three examples were “new,” but attorneys clearly expected jurors to attend to these practical issues, as most of the write-ins in this category were linked to other mitigators on the form, with 40% receiving a code of “new.”

Juries also discussed benefits and collateral effects of an LWOP verdict. This category included straightforward statements: “Life in prison is a harsh punishment” (n = 3 juries), potential messages to others (“His life imprisonment would serve as an example to his children that bad actions, bad choices, and bad friends have consequences”; “Life in prison without release will give defendant the opportunity to reach out to the Hispanic youth on the negative aspects of gang activities and involvement”—the latter offered for two MS-13 defendants), and hoped-for changes of heart (“The imposition of a life sentence without possibility of release would preserve the opportunity for remorse that could lead Christopher Andaryl Wills to disclose the whereabouts of the remains of Zabiallah Alam”; “A chance to repent”). Nearly all of these (83%) were new.

Procedural fairness as a focal concern

Finally, some mitigators did not fit neatly into the three primary FCT categories just reviewed. When given a chance to offer write-ins, 10 different juries described reasons why the death penalty would not result from procedural fairness. Most commonly, juries commented on residual problems with evidence, including specifically mitigation (“The limited amount of personal history for consideration”), or from the guilt phase: “All the testimony in the guilt phase for these counts was [from] convicted felons with extensive rap sheets”; “The defined knowledge of who started the shooting is not without a reasonable doubt.” Further, two juries commented on the performance of either prior counsel (“William Baskerville was ill served by his original lawyer”) or the current one (“Poor defense”).Footnote 10 These evidentiary and lawyer comments stem from just five unique juries, since one jury wrote in the same factor (“Questionable reliability of key inmate witness”) for four defendants, and another wrote in the same factor (on limited personal history) for three defendants.

In four cases, jurors considered a death sentence in light of co-participant sentences, implicating the form of procedural fairness relating to treating people equally (Reference TylerTyler, 2006). Others involved in the crime “are not facing the death penalty, much less (sic) incarcerated,” are “not facing any charges,” or otherwise received less punishment. Just a quarter of these write-ins were coded as new, likely because the outcomes for equally culpable others is a statutory mitigating factor in federal law (“Another defendant or defendants, equally culpable in the crime, will not be punished by death”). In these write-ins, jurors named other people not already mentioned on the form, or in one case, rewrote the existing mitigator—“Lamont Lewis, an equally culpable defendant, will not be punished by death for any of the 11 premeditated murders he committed and may be freed after serving forty years for the premeditated murders he committed” (0 votes)—to remove the future prediction about time served, with the outcome comparison remaining intact (generating 12 votes). Other issues were less case-specific, suggesting more philosophical fairness concerns. Two juries wrote some version of the idea that “all life has value,” and another jury commented on the fact that the federal government had prosecuted the case, noting: “If tried in a New York state court, execution would not be an option.” All of these were new.

Discussion

Using uniquely detailed verdict forms from post-1990 federal capital trials, we examined how often and on what topics jurors added their own mitigating factors to verdict forms. We find that although by no means universal, write-ins were commonplace: four in 10 juries offered one. Write-ins occurred more often on juries that endorsed more mitigators and fewer aggravators and, surprisingly, when they judged a defendant who was not White. Finally, their content suggests jurors consider all three focal concerns, particularly blameworthiness, and a few juries also articulated what we termed a procedural fairness concern.

The frequency of write-ins

On average, 40% of juries given the opportunity offered a write-in, with most offering more than one. Per vote totals, write-ins typically had the support of more than half the jury. Further, jurors demonstrated independence, with over 50% of write-ins coded as “new”—that is, not related to mitigators elsewhere on the form. Interestingly, even among write-ins that we did not code as new, multiple juries used the opportunity to rewrite a proffered mitigator into words that better reflected jurors' understanding of the mitigator, suggesting detailed attention and a desire to align the mitigator with their assessment of what the evidence supports. Although we cannot use these data to assert that jurors were never confused by nor hostile to mitigation, the willingness of about four in 10 federal juries to add to—and sometimes outright correct—existing mitigators, often with substantial support of the jury, suggests that jurors' sense of individualism and personal responsibility is not “hegemonic” (Reference KleinstuberKleinstuber, 2013). Juries can and do contribute additional contextual information, frequently new information.

Intriguingly, the opportunity to extend an additional write-in did not disproportionately privilege White defendants. If anything, it was the reverse: White defendants were, on average, less likely to receive a write-in, and this was true even after controlling for other case factors in a multivariate model, including victim race. (There were only weak victim effects, although notably a subset of cases had limited information on the precise racial characteristics of multiple victims.) Whites were not similarly disadvantaged in total mitigators presented, the percent accepted by the jury, or mitigation vote totals. Mindful that we had only a few variables to test—we lacked, for example, trial transcripts or closing arguments from the punishment phase—our result nonetheless is at odds with careful studies of the death penalty demonstrating Black defendants' disadvantage (e.g., Reference Lynch and HaneyLynch & Haney, 2000, Reference Lynch and Haney2009). Federal and state differences may explain these results, a possibility we discuss below. Additionally, scholars note that pretrial, especially charging, decisions contribute to racial disparities because prosecutors are more likely to pursue a death sentence against Black defendants (e.g., Reference Baldus, Woodworth and PulaskiBaldus et al., 1990). Reference Baldus, Woodworth and PulaskiNotably, Baldus et al. (1990) find that the effect diminishes in the most aggravated cases, and many of the White defendants in our dataset (e.g., Timothy McVeigh, Dylann Roof, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev) committed particularly aggravated murders; several were also associated with White supremacy movements. In future work, we hope to explore the complexities of race and case effects in these data in more detail. However, for present purposes, write-ins appear to signal openness toward mitigation: they were more likely when the jury endorsed a greater proportion of the other mitigators and less likely when they endorsed more aggravating factors. Jurors were least likely to extend this openness to White defendants.

Do jurors have focal concerns?

Our data offer some of the clearest evidence that Focal Concerns Theory (FCT) is an applicable, if not wholly complete, theory of laypeople's sentencing concerns. FCT posits three primary concerns in sentences handed down by judges: blameworthiness, community safety, and a heterogenous category of “practical concerns and consequences of punishment” (Reference Steffensmeier, Kramer and StreifelSteffensmeier et al., 1993).

We found the strongest support for blameworthiness. Two-thirds of write-ins (65%) reflected such concerns, and a high proportion of juries that offered write-ins (78%) wrote on a blameworthiness topic. Over half of these (54%) were coded as “new.” Jurors offered write-ins about the defendant's character; abuse history, neglect, or a generally “rotten social background” (United States v. Alexander, 1973), including failures stemming from governmental agencies and the justice system; mitigated mental state or gang influence; and cultural differences. Clearly, consistent with FCT and more classical theories of retribution, jurors approach mitigation with an eye toward offenders' moral culpability and blameworthiness. Jurors expressed few community safety concerns through their write-ins, with just four explicitly noting that the defendant had a low probability of future violence, none coded as new. Endorsing future dangerousness also failed to predict whether a form had a write-in. Jurors may well have community safety concerns, but strong links between this domain and mitigation were not evident. Any links between safety concerns and final sentences (e.g., Reference Blume, Garvey and JohnsonBlume et al., 2000) await future analyses of these data.

Importantly, our data offer some of the first strong evidence that jurors consider the practical constraints and consequences component of FCT. Multiple juries independently discussed the effects of a defendant's execution on one or more family members and future generations. Jurors also pointed to practical advantages of a life sentence, including the message it sends. It could be argued that such “messaging” reflects general deterrence—for example, an interest in what the sentence will teach others—but we are struck by how case-specific the jurors' write-ins usually were. If given life, the defendant could counsel his own children; an MS-13 member might speak directly to Hispanic youth about gangs; or a defendant, in time, might repent or reveal the location of a body. Like judges, many jurors appear to approach capital sentencing by considering more than an atomized individual, instead recognizing the consequences its decision has on very specific others.

Finally, a small number of write-ins implicated the procedural fairness of a death sentence. We see this as additional evidence that although most mitigation write-ins centered on characteristics of the defendant, particularly his blameworthiness, a subset of capital juries seemingly consider a “multilayered environment” (Reference UlmerUlmer, 2012, p. 11) of the sentencing encounter: flaws in the trial process or evidence, the outcomes for equally (or more) culpable others, and the government seeking a death penalty when a state court would not permit it. Even some factors we coded as representing blameworthiness, such as when jurors suggested culpability on the part of the government, may reflect fairness concerns: conceivably, juries mentioning ways the government failed the defendant or was otherwise negligent (e.g., failing to make rounds in a prison) may believe that a culpable government should not pursue death (see Reference Rountree and RoseRountree & Rose, 2021). How jurors think about the government as a party in the case, and whether the prosecutor is a representative of the same government and system that has previously interacted with or “failed” the defendant, would be a useful area of future research. For now, we simply note the various ways that the state's actions became part of the rationales for sparing the defendant.

Significantly, we do not claim these fairness concerns reflect actual fairness, particularly denunciations of the quality of the defendant's lawyering or the state of the evidence. The CJP project has previously suggested that jurors discuss residual doubts in interviews and that such doubts can predict outcomes (e.g., Reference Devine and KellyDevine & Kelly, 2015). In a perfect world, such concerns seem more properly addressed at the guilt/innocence, rather than the sentencing phase. Regardless of its propriety as actually “fair,” we suggest that jurors, a group that is independent of the government and judges, may have focal concerns that are not fully captured by blameworthiness, community safety and the constraints and consequences of sentences. We view this as an important, theoretically based way to ask questions about jury sentencing, both in the capital context and when juries decide noncapital sentences (see Reference King and NobleKing & Noble, 2004).

Limitations

Our findings are limited in at least two important ways. First, like other nonexperimental jury research, we cannot integrate into our analysis or control for the evidence the jurors actually received, the credibility of witnesses, or the skill with which that evidence was presented.

Second, our project involves federal capital trials, while most death penalty cases are tried in state court. Viewed one way, this is a strength. Federal trials occur in states that do not use capital punishment (as one jury noted in a write-in), which makes these cases comparatively less regionally clustered than state data. At the same time, federal cases are unique in many respects, including, as mentioned, the detail in verdict forms but also in the types of cases prosecuted, the level of resources typically available to both parties, and, perhaps, jury composition.

With respect to resources, the average jury in these data probably heard a better-funded defense compared to state cases. Given that support for mitigation predicted the likelihood of write-ins, better-skilled attorneys may help jurors think about mitigating evidence in creative ways. That said, a 2010 report noted “steep regional differences in defense resources,” and that “federal cases brought in states with a historically strong attachment to the death penalty are more likely to be low cost and disproportionately end in a death sentence” (Reference Gould and GreenmanGould & Greenman, 2010, pp. 52–54). Further, defense lawyers in federal capital cases are often the same as in state cases and bring to the federal cases the same expectations and “local legal culture” as they would a state case (Reference Gould and GreenmanGould & Greenman, 2010, p. 56). Hence such findings caution against overstating differences between state and federal cases, even as we cannot rule out lawyering and resource effects.

With respect to jury composition, federal circuits draw from larger, more suburban areas compared to urban areas of most state cases and therefore overrepresent Whites and people of higher SES (e.g., Reference Cohen and SmithCohen & Smith, 2010; Reference Rose, Casarez and GutierrezRose et al., 2018). White overrepresentation in capital cases is not specific to federal cases (Reference Baldus, Woodworth, Zuckerman, Weiner and BroffittBaldus et al., 2001), and Gould and Greenman suggest a role for local culture: “If the local culture supports capital punishment and the death penalty is a regular aspect of state criminal law practice, it is not surprising that federal jurors in that state would be as likely to impose the death penalty as state jurors” (Reference Gould and GreenmanGould & Greenman, 2010, p. 55). Nonetheless, given the absence of information on the racial identities of the jurors filling in these forms, we have no way of testing any relationship between jury composition and the presence of write-ins.

Even if federal prosecutions are different, a key question is whether federal jurors' reasoning processes are somehow unique. We have no strong basis for making such an assumption, and some limited data support our view. A Federal Defender gave us access to the 14 verdict forms used in New York State for the brief period (less than a decade) that it permitted the death penalty (a 15th form was not made public). All but one of these forms (n = 13) mimic federal ones by having an opportunity for write-ins. Of this small number, seven included a write-in (54%, or 50% if we assume the one not made public failed to have a write-in), not far from, and exceeding, the 40% we observed. One write-in was illegible, but reading through the remainder indicates that, consistent with our data, most commonly (5 of the 7) juries offered blameworthiness concerns (e.g., mental state, poor parenting, untreated psychiatric issues from childhood, being under the sway of another). Additionally, one jury also wrote what appeared to be attention to practical concerns (“He is a father and has a son”; “Compassion for both families involved …”) and another discussed the ability of the defendant to handle a life sentence. Again, these are small in number and not necessarily representative of all state cases; nonetheless, the broad descriptive patterns and focal concerns we observed seem not to depend upon having federal jurors fill out these forms. Instead, results likely arise from the structure of the verdict sheet, which prompts jurors to attend in a formal way to mitigation. In this way, our data show that all capital verdict forms—state and federal—can offer jurors write-in opportunities and should expect jurors to develop independent, yet appropriate topics as mitigators.

Conclusion

To suggest, as we do, that research on jury decisionmaking, particularly mitigation, has been incomplete is not to argue that decision makers - jurors or judges—can fairly decide whether to sentence another human being to death. The bulk of empirical research shows the capital sentencing system in the United States to be a failure: it does not meet key goals (e.g., Reference Nagin and PepperNational Research Council, 2012), contains inexplicable and unjustifiable biases in outcomes (e.g., Reference Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns and JohnsonEberhardt et al., 2006), and in multiple ways, it lacks procedural fairness (e.g., Reference HaneyHaney, 2005). Our peek into the “black box” of deliberation is aimed instead more narrowly at observing and interpreting signals of jurors' reasoning about mitigation. We thereby complicate the existing scholarly understanding of jury decisionmaking in this area, finding a good number of juries take up the invitation to offer their own, novel take on mitigation, particularly if, in general, they support other mitigators and fewer aggravators. We also offer some of the first evidence that Focal Concerns Theory is an appropriate way to begin to capture jurors' sentencing concerns. In offering thoughts on mitigation, these juries attended to moral blameworthiness and, to a far lesser extent, community safety. They also documented a concern for the practical effects and fairness of the sentences they hand down. Our data cannot show that these juries correctly—in legal or moral terms—debated and considered mitigation during deliberation, or indeed, that defense counsel adequately represented the defendant or the Government ethically and constitutionally prosecuted him. We can say, however, that when “speaking” on this topic through verdict forms, juries were neither monolithic nor filled with hegemonic individualists. These juries independently offered nuanced, detailed-oriented, and contextualized reasons for a sentence other than death.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the FDPRC for answering our questions and providing supplemental information. A number of research assistants at both institutions aided us, especially Lily Baitler, Adrienne Epstein, Isabella Prines, Lauren Loader, Faridhe Puente, Brooklyn Rodgers, Rhianna Rose, Samanta Suheen, Evelyn Voelter, and Willis Wiest.