In an enticing 1856 article for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Hans von Bülow offered an assessment of Franz Liszt's leadership in reforming keyboard virtuosity and remarked:

Given the sovereign position that the keyboard has not only taken but conquered on the playground of virtuosos par excellence in today's music world, reform has here been needed most, and has occurred in a most decisive, and for other instruments most authoritative, manner. Joseph Joachim, who in a way can call himself a student of Franz Liszt, may perhaps be able to achieve a similar reform for violin playing [Violinspiel].Footnote 1

The Golden Age of virtuosity had been on its way out for several years,Footnote 2 and this was having an impact on violin performance. And yet, violin programming in the musical metropolises London and Paris was slow to adapt. For von Bülow, if anyone could effectively close the door behind Virtuosentum in the violin world, it was Joachim, whose classical performance style – as evident at the Lower Rhine Festival in 1853 – proved his exemplary artistry.

As recent work on Joachim's virtuoso years has shown,Footnote 3 his repertoire during the 1840s encompassed far more than German classics. It accommodated plenty of virtuoso music by H.W. Ernst, Charles de Bériot, Ferdinand David, and Henri Vieuxtemps, as well as his own substantial, virtuoso compositions, composed for his London tours in 1847, 1849, and 1852.Footnote 4

As this article argues, Joachim's programming did not change overnight: the shift from performing and composing virtuoso pieces to identifying himself with lofty and serious works happened gradually. One vehicle through which Joachim transformed the state of ‘violin playing’ of the 1840s was the violin romance. Joachim's romances – misunderstood in terms of genesis and almost unknown today – offered a suitable vehicle for stylistic change.Footnote 5 Unostentatious and yet enchanting, the main qualities of the older French ancestor – the vocal romance – were simplicity, naïveté, a bucolic element (champêtre), and, according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a plainness that resisted heavy ornamentation and virtuosity.Footnote 6 The romance's beauty enticed: typically short and sweet, it gave audiences pleasure.

Joachim, who spent three months in Paris in early 1850, used the aesthetic of the romance to transform not only the state of violin playing but also the violin romance itself. Two simple romances he composed in 1850 were followed by a third romance in 1857. The third was, in effect, a Bravourstück in disguise, exhibiting none of the older Golden Age virtuoso tricks, such as flying bow strokes, that had fallen out of favour. Rather, in Joachim's third romance, the conspicuous, ‘1840s’ virtuosity merged into ‘shape-oriented virtuosity’ (‘Gestaltende Virtuosität’), a term used by a critic to describe Joachim's interpretation in a concert of 1854; specifically, a type of virtuosity ‘which makes it its task to illustrate to us the characteristic moments within the works of our good masters’.Footnote 7 Later nineteenth-century composers including Max Bruch, a close friend of Joachim, adopted Joachim's romance model, negotiating between melodic simplicity and violinistic demand, resulting in lyrical pieces in which virtuosity was an undercurrent, hidden but present.

The romance genre offered a training ground for a young violinist-composer; it also featured a tie to Beethoven, whose oeuvres include two violin romances, allowing Joachim to express his continued classical allegiance. At the same time the genre stood with one foot in the world of opera, and its effect was pleasing to mainstream concertgoers without pushing the buttons of audiences tired of flashy virtuosic fare. The romance was a genre ‘antique’ enough and, by the mid-nineteenth century also ‘empty’ enough, to serve as a vessel that could be ‘filled’, signalling Joachim's own interests: those of a violinist-composer negotiating between edifying his audiences and being the violinist of expert virtuosic skill who enjoyed proving his mastery over the violin.

Joachim's three-pronged transformation of violin playing consisted of a) a change in programming favouring romances instead of 1840s-type Bravourstücke, b) his own romance compositions, and c) particular stylistic touches particularly in the late romance, the second movement from the Hungarian Concerto, highlighting a new ‘shape-oriented’ virtuosity,Footnote 8 thereby presenting a new performative approach. In 1861 Hanslick described Joachim's performance of Beethoven's romance as embodying ‘undecorated greatness’, ‘simplicity’, and ‘Roman seriousness’.Footnote 9 No bravura piece was offered on the programme and its absence was not even noted. The state of ‘violin playing’ had changed.

Genealogy of the Violin Romance

Because of the romance's rich history – reaching back to the wandering troubadours – and because of its extremely broad definition – by 1828 defined as an ‘instrumental composition of a somewhat desultory and romantic cast’Footnote 10 – offering a comprehensive historical overview is futile. Indeed, the literature about the operatic romance is exhaustive but only partially relevant to the instrumental romance, while the existing literature on the violin romance is sparse and of limited use. For example, Chapel White writes that in the decades around 1780, ‘no movement is designated a “romance” unless it presents an initial, closed section made up of regular, well-defined phrases – a section, that is, corresponding to the vocal romance’.Footnote 11 But White focused on Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824) and did not extend his studies to nineteenth-century works. Furthermore, White did not elaborate on the intriguing genre transfer as violinist-composers of opéra-comique also turned to romance composition in standard violin concertos, which were taught throughout the nineteenth century. In fact, Beethoven's widely-known two romances Opp. 40 and 50Footnote 12 can be traced to a shared discourse with the Paris conservatoire composers,Footnote 13 and, furthermore, Joachim's own violin-pedagogical ancestry can be traced via his teacher Joseph Böhm (1795–1876) to the same institution.

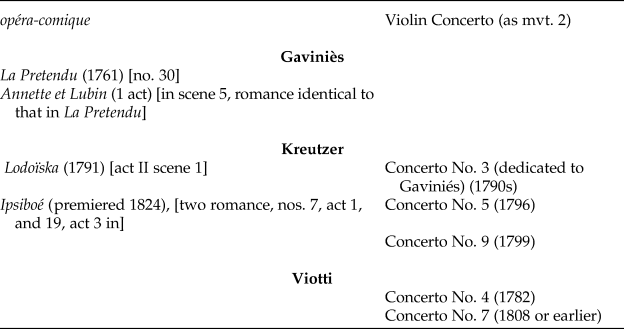

Thus, rather than understanding the violin romance's ancestry as a branch of the instrumental romanceFootnote 14 – there would certainly be enough piano romances in Joachim's circle that one could address, including those of the SchumannsFootnote 15 – the violin romance in Joachim's hands deserves its own genre-specific story, which begins with the violinist composers associated with the Paris conservatoire who had one foot in the opéra-comique world (Table 1).

Table 1 Romance in opéra-comique and in Violin Concertos by Paris Conservatoire Violinists

The main three violin representatives at the Paris conservatoire were Pierre Baillot, Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Pierre Rode. All violin pedagogues in the late 1700s, their efforts were published in the Méthode du Violon … Adoptée par le Conservatoire pour servir a l'Etude dans cet Etablissement.Footnote 16 Giovanni Battista Viotti, who lived and worked in Paris for a time and taught all three of the above-named,Footnote 17 is considered the founding father of the Parisian violin school. Pierre Gaviniès – whom Viotti described as ‘the French Tartini’, taught violin at the Paris Conservatoire from 1795 until his death. Gaviniés was credited with two of the earliest operatic romances,Footnote 18 while Rodolphe Kreutzer – whose third concerto was dedicated to Gaviniès – followed in the latter's footsteps as a violin virtuoso, pedagogue, and opéra-comique composer.

The operatic romances are trifles. As expected in the opéra-comique, whose musical numbers – romances included – were separated by spoken dialogue, romances were meant to be simple. The simplicity of form, strophic or ABA designs, minor–major contrasts, and sweet text and tone aimed at something else than effect in a spectacle sense.Footnote 19 They wrapped the listener into a state of sentimentality, which, if not ‘effectful’, was still enthralling.

Gaviniès's romance in G major, Qu'il est doux, qu'il est charmant (c. 1755), is written in a ‘simple and slightly archaic style’Footnote 20 and falls into a five-part form with three strophes featuring a charming theme in G major (text: ‘Qu'il est doux est charmant, Le plaisir qu'on goûte en aimant’), alternating with couplets in G major (8 bars, moving to V) and G minor (8 plus 16 bars). Similarly, Gaviniès's romance in C major from La Pretendu (1760) is an essay in elegance, as expressed in the simple melody of the opening 16-bar sentence. The basic idea in C major contains stately, crisp two-crotchet gestures, and an elegant appoggiatura pair while the repetition of the basic idea moves to the dominant. The continuation visits A minor and ends on V/A minor, before giving way to the cadential idea, which returns the theme to the home key.Footnote 21

The short romance from Lodoïska (1791) is in a 6/8 lilting metre; the accompaniment of broken triads gives it a pastoral feel.Footnote 22 The whole piece falls into a sentence structure. The basic idea traces a i–V in a rocking quaver melody (bars 1–5); this basic idea is repeated (bars 6–9). The continuation (bars 10–12) lightens the mood briefly into C major, before offering an expanded cadential idea; that expanded cadential idea is repeated, and followed by a brief 6-bar codetta.

The romance from Ipsiboé (1824), in A minor and cut-time, uses the French couplets form.Footnote 23 Used throughout the Romantic period by Hector Berlioz and others, this form alternates verses and refrains; the tone is often pathetic and sentimental, the style simple. After a brief introduction that features a minor-mode reference to the ‘La Marseillaise’ the first couplet (verse) ensues with a melody descending down the interval of a fifth while the dotted rhythms from the introduction remain underneath the melody. The Refrains bring A major and a theatrical declamatory style, making use of repetitive quavers on single pitches and of harmonic variation, as the dominant, E major, appears with a raised fifth scale degree (B♯) in the melody, clashing with the B in the bass. The second verse and refrains are varied – decorated – and followed by a coda, thus yielding altogether a 5-part form. The mood is serious in the verses and uplifting in the refrains.

The violin romances of Kreutzer, Gaviniès, and Viotti, likewise prioritize the same intense potentiality for lyricism. Kreutzer's Romance in A major from Concerto No. 3, in ABA form, is a calm and ornate token in alla breve. The piece opens with a pastoral circular triadic figures in the violins (a–c♯–e–c♯–a–c♯–e–c♯) before the solo presents a theme in which large expressive intervals abound. In sentence structure, the basic idea stays in A major (bars 2–5); the repetition of the basic idea (bars 6–9) ends with a I:HC; the continuation phrase (bars 10–13) tonicizes E major while the violin executes ornate fast ornaments and trills; and the cadential idea, expanded by one bar (bars 14–18), heightens the level of decoration in the violin and leads to a varied repeat of the theme, this time condensing it, bringing the A section to a close. The B section, in A minor, opens with an expressive ascending sixth – continuing the large-interval gestures from A – and offers an 8-bar antecedent (to V) and an expanded consequent (ending with a i:IAC) and a transition towards V to prepare the return of A.

Kreutzer's Romance in A minor from Concerto No. 5, in ABA form, opens with a brief introduction of maestoso dotted rhythms in 3/4 before offering a melancholy A minor-theme in small ternary aba′ form, with a lilting slow waltz quality. The first theme, a, is closed and cadences on C major, III. The b (bars 13 [with pick-up]–16) is loosely knit, ending on V/A minor. The a′ returns the opening theme to A minor. The middle B section is in A major and briefly visits the dominant E, before returning to the home key. The minore A section returns and draws the piece to a close.

A specifically operatic heritage is evident in Kreutzer's Romance from Concerto No. 9, where fermatas before the A′ and A″ sections invite ad libitum improvised cadenzas. In addition, the B and C episodes add a florid style relying on demisemiquaver garlands.

Thus, the ‘romantic’ and lyrical qualities that ‘vocal and instrumental settings entitled “romance” … continued to express’Footnote 24 since the eighteenth century, included, specifically, a continued focus on the Rousseauian simplicity – ‘une mélodie douce, naturelle, champêtre’Footnote 25 and prioritized relatively strictly sectionalized ABA[′] ternary (Kreutzer Nos. 3, 5; Viotti Nos. 4, 7; Gaviniès's romances) or 5-part forms (Kreutzer's Concerto No. 9 and Ipsiboé);Footnote 26 minore or relative/parallel key contrasts are paramount; and often the opening A section featured ‘closed’ thematic blocks, sometimes in 16 bars (aa′ba″);Footnote 27 the ‘Fantasia topic’ also stood out.Footnote 28

In Paris, the romance never truly disappeared. As William Cheng has written,Footnote 29 the genre attracted primarily amateurs in the 1830s and 40s. The places in which to hear violin romances included musical salons. ‘The abundance of this musical commodity called the romance’, the critic for the Gazette musicale declared, ‘should alarm neither those who consume it nor those who produce it …. The Parisian has always enjoyed easy pleasures, and of course, of all musical pleasures, the romance … can very well be regarded as the easiest.’Footnote 30 By 1835, the genre, at least in Paris, ‘had become a critical buzzword for dilettantism … and a veritable cultural institution’.Footnote 31 Thus, although some writers claimed as early as 1818 that ‘[t]he domain of the romance has prodigiously increased in our time … [and] now has every characteristic and takes every tone’,Footnote 32 scholars including James Hepokoski, Annegret Fauser, and Stephen Rodgers have shown that the genre could still afford important insights in the mid-nineteenth century, owing to its potential for generic intermixture,Footnote 33 ‘promiscuity of genre’ or transfer between stage and salon,Footnote 34 and dialogues with vocal song forms.Footnote 35

It is admittedly difficult to see how Joachim might have reconciled, in performance or composition, features of ‘easiness’, ‘dilettantism’, ‘simplicity of song’, ‘straightforward melody’, and expression of ‘sentiments that everyone feels’,Footnote 36 given that none of these elements is typically associated with Joachim the dignified Geigerkönig's own music or performance style. A critic for Le Ménestrel suggested that ‘several writers also denounced the romance for failing to contribute to the progress of art’ and ‘paralyzing’ the musical advances of ‘our forefathers [Beethoven, Weber, Rossini, and Meyerbeer]’.Footnote 37 Yet, Joachim's romances – while celebrating ‘straightforward melody’, simplicity of form and common sentiment – did not ‘paralyze’ the musical advances of his forefathers; in fact, he used one forefather's set of romances to advance the genre according to his own imagination. Joachim's lyricism, one of his praised qualities, may well have intensified and evolved during his Paris sojourn.

Filling a Niche: Performing Beethoven's Romances

Joachim's performances of Beethoven's Opp. 40 and 50 romances – and the three of his own in B-flat major, C major, and G major – helped him advance his maturity from a young virtuoso to a serious artist.

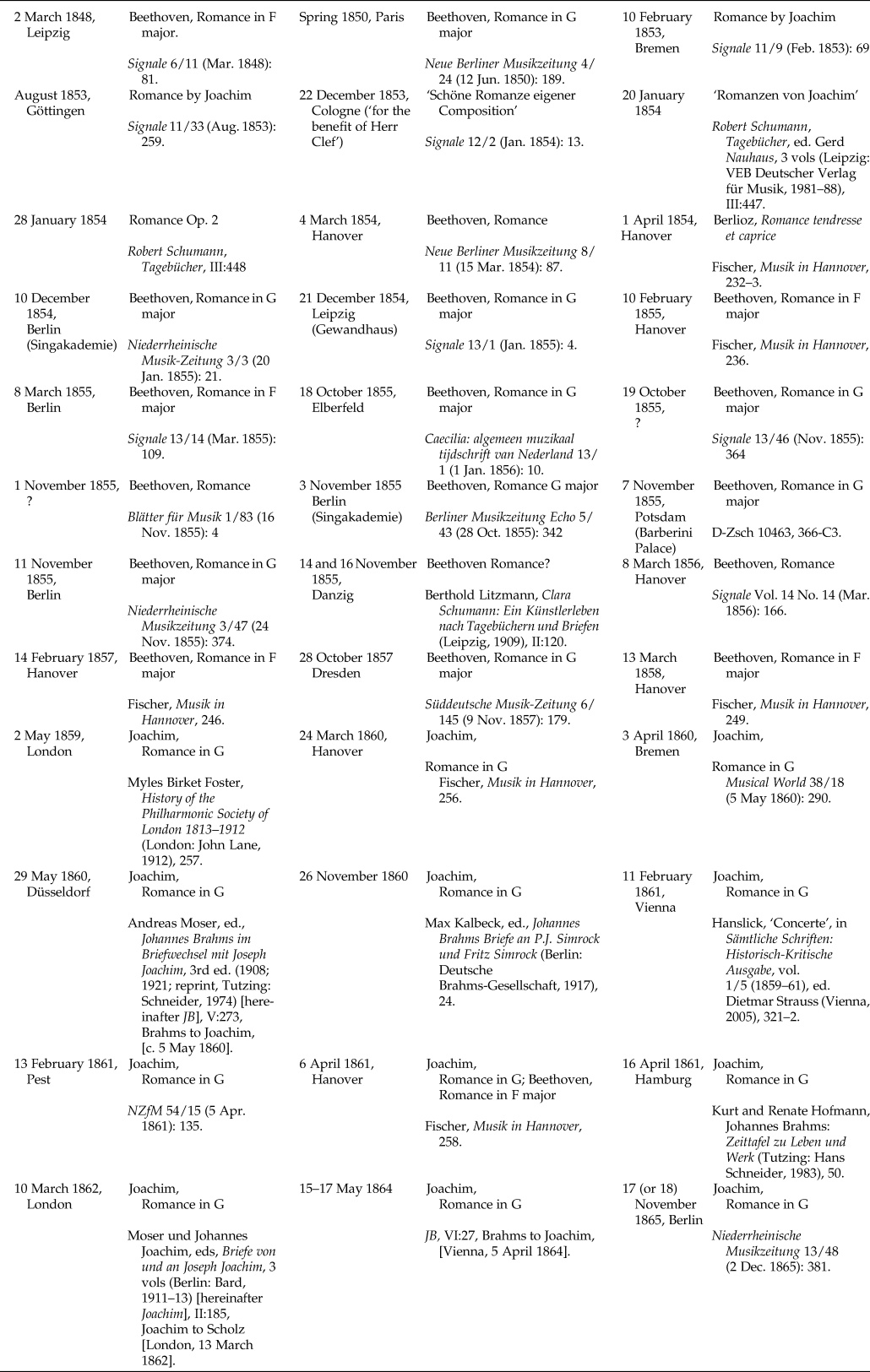

Joachim's repertoire of the 1850s (especially after 1855) departed conspicuously from his concerts of the early 1840s until about 1853,Footnote 38 which, pace Andreas Moser, included many more compositions of H.W. Ernst, de Bériot, and F. David than acknowledged, in addition to Joachim's own Andantino & Allegro scherzoso Op. 1 (1849), Fantasy on Hungarian Themes (1846–50), and Fantasy on Irish [Scottish] Themes (1850–52). An overview of Joachim's performances of romances from 1848 up to 1865 is presented in Table 2; they are mostly Beethoven's, but also Joachim's, and one poignant jewel by Berlioz. Although by 1852 Joachim's romances in B-flat and C major were published,Footnote 39 only occasionally did he offer them in public himself, though probably more frequently at private concerts.Footnote 40 The transition from preferring Beethoven's romances to performing his own Hungarian Concerto romance becomes clear over a stretch of about a decade. Often Joachim performed his Romance Op. 11 without the other movements.Footnote 41

Table 2 Joachim's Performances of Romances between 1848 and 1865

In Joachim's view, Beethoven's romances were central to educating audiences in becoming more discriminatory listeners, as they abandoned their hunger for ‘tawdry’ sensationalism and musical bonbons full of effects. One would have expected critics witnessing Joachim's programming to give a nod to the vocal romance, that it was a texted sibling with national and other genre stereotypes, such as features of form, narrative, and lyrical song, some pointing to the French Conservatoire composers. And yet, critics rarely commented on genre. Beethoven's romances were heard without the revealing qualities of the romance being acknowledged. Presumably the way that Joachim performed classical works created a blind spot for critics who noticed the classical nature of music and its formidable interpretation while other music presented in the same concert sometimes did not seem worthy of critical investigation. One reviewer found that a Paganini Caprice somehow ‘lost in significance’ alongside serious classical repertoire:Footnote 42

It is peculiar that both [Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim] stand on a foundation of the most solid art conception and understanding of art, that their repertoire consists almost exclusively of classical, or at least elevated, compositions, and that this is how one can judge their artistic point of view …. As a result, variations by Paganini, which were presented at the end of the concert and were played excellently, lose their meaning for us.Footnote 43

After acclimating audiences to Beethoven's relatively unknown romances from 1848 onward,Footnote 44 Joachim presented his own romances as the next step.

Paris Encounter, 1850, and Joachim's Two Early Romances

Although Joachim was deeply familiar with Beethoven's romances by 1850, he appears not to have modelled his own romances in B-flat and C major directly after Beethoven's. Rather, Joachim attempted a synthesis that brought together a modified Beethovenian rondo form with French influences to which he had been exposed during his three-month-long Paris sojourn in spring 1850, which occurred right before his move to Weimar in the summer of 1850.

Paris was known at the time as the cradle of violin virtuosity. For a young aspiring violinist, to prove himself in Paris was meaningful.Footnote 45 Before deciding to move to Weimar and join Franz Liszt as concertmaster (as Joachim did in October 1850), there was some discussion, mainly from Joachim's family, about moving to Paris. Joachim's opinion, though, was clear in 1848: ‘To Paris I definitely won't go’ (‘Nach Paris gehe ich aber keinesfalls’),Footnote 46 instead he chose Weimar. Although little has been written about Joachim's long stay in the French capital, by spring 1850 his attitudes had changed. He considered himself ‘less of a philistine’ and had warmed up to Liszt: ‘The antipathy that I generally felt towards him has now given way to an equally strong predilection, given that I've come to know him better. Perhaps I am less of Philistine since Paris?’.Footnote 47 Perhaps Mendelssohn had instilled in Joachim a certain distance towards Paris in the early 1840s; but by 1850 that distance had turned into flirtation.Footnote 48

Upon his return from Paris in May, Joachim was brimming with ideas. He wrote to his brother Heinrich: ‘Since my return from Paris I have composed … several small pieces for violin and piano’.Footnote 49 What Joachim included in this count is unclear; he may have composed both romances, Op. 2 and the C-major shortly upon returning from Paris, but at least the terminus ante quem of the former was October 1850.Footnote 50 The terminus ante quem of the C-major romance was supplied by its publication year, 1852.

Joachim arrived in Paris in late JanuaryFootnote 51 and left in April. Whereas the repertoire performed by the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire – founded in 1828 – would have been partial to Beethoven, Haydn, and French operatic and sacred works,Footnote 52 salon performances would have prioritized smaller, entertaining pieces. He performed at several salons,Footnote 53 including, on February 21 [1850], with pianist Madame Wartel at Erard's Salon,Footnote 54 and with Coßmann and Wartel again at Erard's Salon on February 28, March 7 and March 21.Footnote 55

Joachim was invited to perform at the opening night of Berlioz's newly founded concert series ‘Grande Société Philharmonique de Paris’ dedicated to ‘vocal and choral concerts every month on Tuesday evenings’Footnote 56 and so deepened his familiarity with a composer he had first met in Prague in April 1846.Footnote 57 ‘The opening concert on 19 February 1850 was an undoubted success and the society subsequently gave a number of notable performances’.Footnote 58 Joachim presented his cheval de bataille, Ernst's ‘Romance’ and variations from Rossini's Otello; the programme also featured Berlioz's La Damnation de Faust (but not act IV, which contains the romance de Marguerite), excerpts from Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots (‘Benediction of the Swords’) and from Mehul's Joseph (aria by Roger), and ‘Aria and Chorus’ from Iphigénie en Tauride, sung by Pauline Viardot-Garcia (1821–1910), whom Joachim had known since 1843.

Though on February 19 Joachim's performance of Ernst's ‘Romance’ was the sole representative of the genre, there is no doubt that his three-month Paris sojourn not only brought valuable personal relationships with French performers and visitors to Paris – the Wieniawski brothers, Pauline Viardot Garcia, Thérèse Wartel (1814–65),Footnote 59 Bernhard Coßmann (1822–1910), and, of course, Berlioz – but also provided a context where romances counted as particularly popular fare. At the ‘5th concert’ of ‘Henri Blanchard du 11eme arrondissement’ on 17 March 1850, for example, Joachim again played his Ernst piece; the rest of the programme also featured the Wieniawski brothers and a ‘Romance de la Fée aux Roses’ (by Charles Ponchard).Footnote 60

Pauline Viardot, who had already published two albums ‘accompagnées de lithographies en rapport avec le sujet littéraire’ with short vocal pieces, including two romances in 1843 and 1849,Footnote 61 was, according to music critic and composer Henri Blanchard, a connoisseur of the romance genre: ‘The woman is very fit to spin us evenings and mornings of gold, silk and music, especially romances’.Footnote 62 Among the pieces in Viardot's 1843 collection is ‘Adieu, les beaux jours’, a sentimental strophic romance in C major; its opening melody acts like a refrain, A, and alternates with two sections in different keys. These popular (‘très courant’) pieces were simple and short, to appeal to the bourgeoisie, and sold separately.Footnote 63

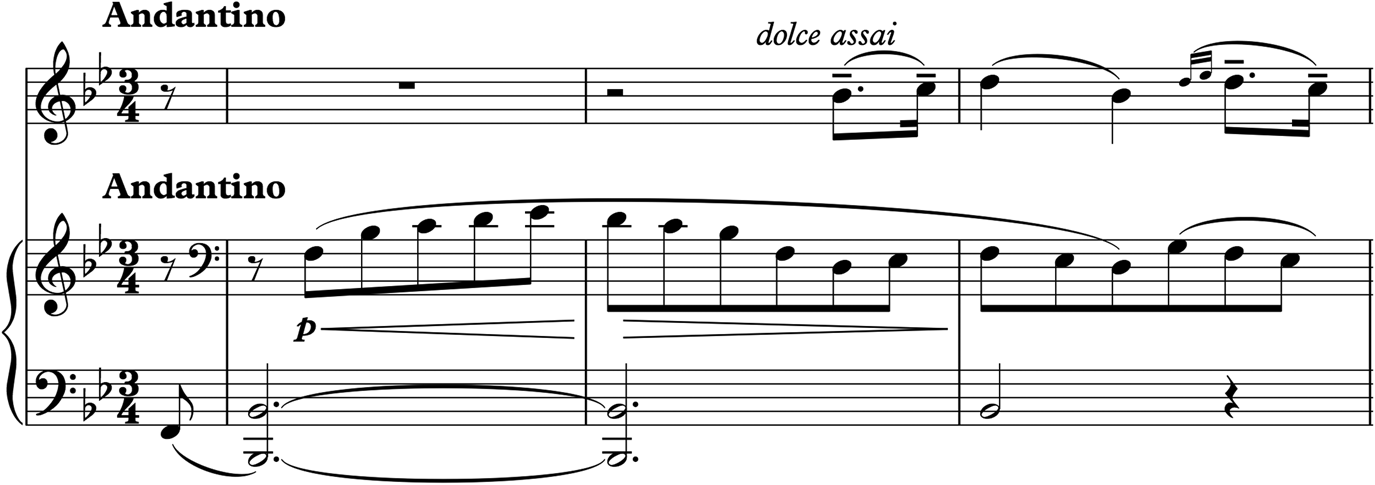

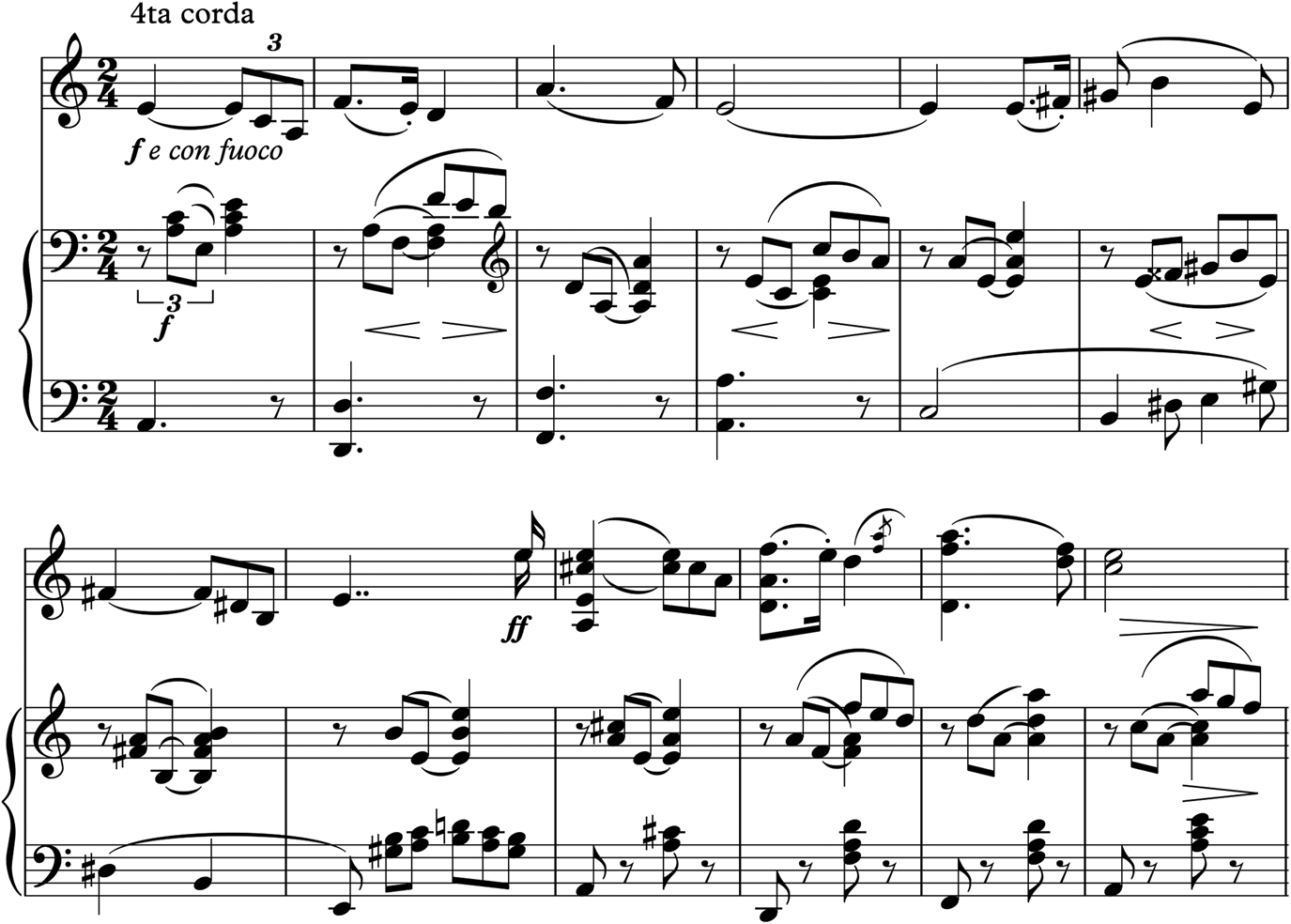

Could Joachim have injected this cultural exposure to a context in which the romance flourished into his Romance Op. 2 with memories fresh from Paris? Perhaps. In his first romance of 1850 Joachim observed most closely Rousseau's archetype of the French romance and its simplicity, sentimental pathos, and pastoral air (champêtre).Footnote 64 Owen Jander has linked the middle movement of Beethoven's Violin Concerto Op. 61 to the champêtre quality of the romance genre; in fact, Jander averred that the Larghetto of Op. 61 is a romance on account of its archaic and pastoral qualities. Arguably, Joachim achieved an even more intense sense of pastoral calm in his Romance Op. 2, which begins with a brief harp-like broken-arpeggio introduction. The A section opens simply, with an internal small ternary outlining a ‘naïve’ melody in B-flat major. The main motive – a pick-up gesture with two crochets descending in a third – is short, almost galant, fitting the French stereotype of an ‘antique’ sound (Ex. 1).

Ex. 1 Joachim, Romance Op. 2 (opening)

Using the orderly older violin romance structure, the B section is clearly separated by a thin double bar, reminiscent of the old French violin romances. Joachim also uses the B section for a minore contrast. The ‘agitato e espressivo’ now supports a sentimental mood (Ex. 2).

Ex. 2 Joachim, Romance Op. 2 (bar 36)

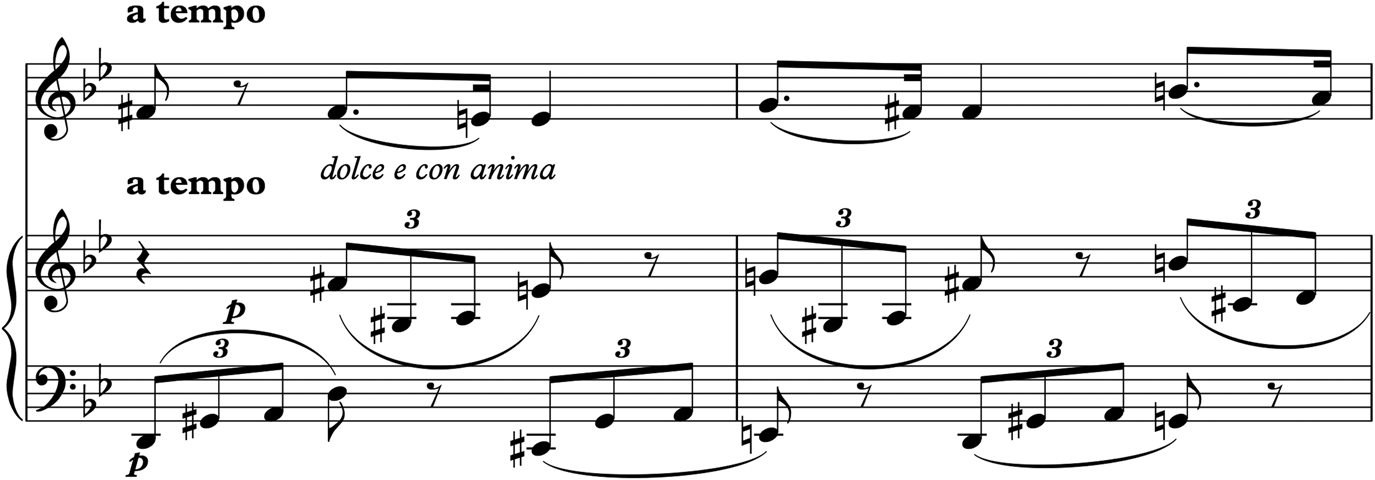

Then comes the crux: a formal deviation via an extra section in D major, marked dolce e con anima and featuring a delightful melody involving metric modulation (it feels ‘in two’ but is ‘in three’). In short, instead of the expected B-flat major double return, which would present the opening theme in the tonic key, we enter into an ambivalent section. In the end, neither the theme nor the key is right. The busy accompaniment in quaver triplets appears as ‘spilled over’ from the B section in G minor (Ex. 3).

Ex. 3 Joachim, Romance Op. 2 (bar 60)

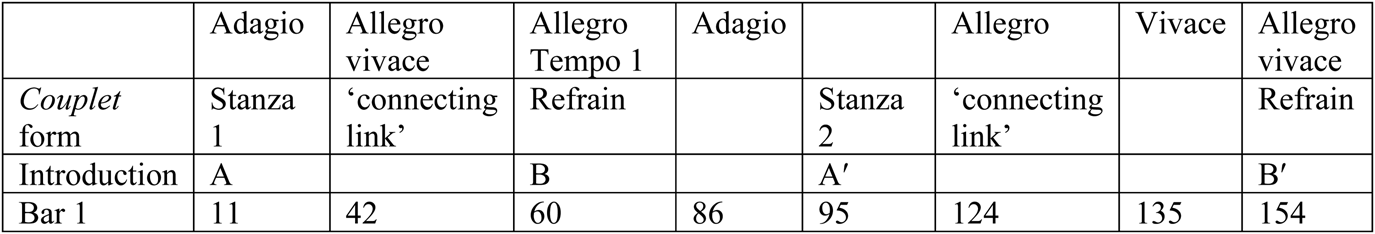

Then, in an effort to redirect this excursion, Joachim recapitulates the minore passage in the tonic key. The overall structure remains a hybrid: A (aba) – B (minore) – C (extra!) – A′ -B (major) – A″ (coda). The extra section might have been motivated to achieve harmonic nuance, as using mediant and submediant relations as tonic substitutions was a common device in Joachim's compositional circle around 1850, favoured by the Schumanns and Mendelssohn (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Joachim, Romance Op. 2 (formal diagram)]

The continuation of the B″ section and return to the last (abridged) A″ is the most poetic part of this romance. Building a rising figure (scale degrees 1–5–8) with the rising-fourth pick-up of the opening, Joachim now fully invokes the bucolic quality of the music by lingering, for the last 15 bars, on this figure in the bass, against the violin in the high register, with disappearing (perdendosi) dynamics. The last A″ offers only a glimpse, as if saying ‘farewell’: only the galant pick-up gesture is revisited once with an abbreviated second crotchet (now a quaver), and then in augmentation, with the first crotchet turned into two full bars (Ex. 4). Strengthening the bucolic character, Joachim repeats the rising figure incessantly, adding a circular metaphor to the piece, which may render this romance a strophic variation.

Ex. 4 Joachim, Romance Op. 2 (bars 100–114)

Stephen Rodgers has observed, ‘French strophic song form with verse and refrain [was] often referred to … by one of two names: romance and couplets’.Footnote 65 We could redefine couplets as strophic form or sometimes as verse–refrain form. Viewed as strophic form, our understanding of this romance does not quite account for the ‘C’ part but A and B, and A′ and B″ could potentially be viewed as two verses, followed by an abridged last glimpse of A″. The repetitive (rotational) nature of the romance could well fit the pastoral interpretation of its ending: the repetitive triplet-motive could serve as a metaphor for the three rotations of the romance. Thus, Joachim's Op. 2, even if featuring an expanded possibly Beethoven-inspired rondo form, still shows more than a nod to the French romance via clear-cut major–minor–major design, harp-like introductory material, and pastoral motives with metaphorical potential stemming from the rotation principle.

In October 1850, some months after returning from Paris, Joachim moved to Weimar where the works of Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt were frequently performed and discussed, which expanded his artistic horizon significantly. Though the exact date of the second romance in C major is unknown, it definitely originated between the Paris trip of 1850 and June 1852, when it was first published in an addendum to the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.Footnote 66 By that point Joachim had had significant interactions with Berlioz.

In March 1852, Benvenuto Cellini (1837) was performed in Weimar. Joachim was concertmaster. Although the performance may not have included the cavatina ‘Ah, que l'amour une fois dans le coeur’ – withdrawn before the premiere in 1838 – in April 1854 Berlioz asked JoachimFootnote 67 to perform the violin romance version of the cavatina, now renamed ‘Rêverie et Caprice’ Op. 8 or Romance tendresse et caprice. The Berlioz romance is an iconic example of the French romance. Opening with an introduction in F-sharp minor, the wistful romance melody breaks through to A major, announced by a bar of broken arpeggios imitating the harp. Berlioz's sound, orchestration, and melodic treatment of the violin, struck a chord with Joachim, who wrote to his brother in March 1852: ‘The opera by Berlioz, Benvenuto Cellini, was performed here a few days ago (thanks to Liszt's enthusiasm for the arts!), and I find so many new, and exciting elements in it that I would like to offer the composer my personal thanks for the inspiration that his music has brought to me’.Footnote 68

Joachim's Romance in C major unfolds in a ‘rotational’ five-part rondo form ABA′B′A″ with the A sections in C major, while the episodes visit A minor (B) and A-flat major/A-flat minor (B′). The initial A section is ‘closed’, consisting of ‘regular, well-defined phrases’,Footnote 69 which corresponds to White's key markers of the conservatory-style romance.Footnote 70 In a wistful enharmonic twist, the last episode ends on V of D-flat minor (A-flat minor); then the fifth, E♭, is reinterpreted as D♯, the leading tone of E major, before descending stepwise down to C major.

The B section is a sonorous G-string-theme with triadic motion (Ex. 5). The G-string is a particularly compelling timbre in Joachim's romance, corresponding to Baillot's description of the lowest string's power to evoke the colour of the horn.Footnote 71 To exemplify this link between the horn and the G-string, Baillot offers an excerpt of a romance by Martini, titled ‘cantabile’. Here, as in Joachim's Romance in C major, the triadic nature and the G-string together support a pastoral reading. Joachim exploited the G-string's characteristic sound whenever he could. Noteworthy is that Berlioz's Romance Op. 8 also specifies the G-string timbre in one passage, which happens to be triadic as well (Ex. 6). Though the similarity to Ex. 5 is coincidental, we may nevertheless note that the violin romance apparently has an affinity to a darker timbral imagination.

Ex. 5 Joachim, Romance in C major (bars 61–72)

Ex. 6 Berlioz, Romance Op. 8

More generally, Joachim's Romance in C major would have allowed him to showcase his skill of sound production in the simple melody of the A section. In the understanding of the French conservatory composers, sound was cultivated with a focus on both bow technique and the violin's resemblance to the human voice.Footnote 72 The French violinists knew first-hand the revolutionary advances of the Tourte bow (1790). The velvety, smooth connectivity achieved with the Tourte bow could shine in a romance; by prioritizing beautiful sound, a violinist of the early 1850s could leave an impression that did not call for the earlier decade's dazzling bouncy bow strokes.

As I have argued elsewhere,Footnote 73 Joachim's exposure to French influences may have altered his views on the production of violin sound. Baillot had argued in his L'Art du violon that the art of performing a ‘simple song’ (‘chant simple’) like an air or the romance relies not on outward activity or manner, but rather in a way of being immersed in the spirit of a composition:

Far from all embellishment, one shall play this passage in its simplicity in order to give it the melodic charm that comes with it … It is not a matter of foregrounding oneself, but only that one is inspired by the inner spirit of the composition.Footnote 74

Joachim's Romance in C major capitalizes not on virtuosity and effect but on plain lyrical sound. As Joachim knew, simplicity in a composition was not a disadvantage, quite the contrary. It allowed proving his most basic asset: a singing cantabile. Thus, the Romance in C major brought together elements of pastoral feel, simplicity, and formal clarity, in short, an aesthetic directed at the audience's enjoyment and pleasure.

Joachim in Review – a ‘shape-oriented’ Virtuosity

Some contemporary comparisons of Joachim's new ‘virtuosity’ to older types from the 1840s provide some insights about how Joachim went about in promoting the romance as a suitable vehicle for changing virtuosic expectations in violin music.Footnote 75 Shaping the music with nuanced details while not compromising large sound and an overall ‘grandiose style’ was a violinistic virtue almost absent in the 1840s critical discourse. Critics of Joachim's concerts in the 1850s often expanded on his ‘highly developed virtuosity’, which on occasion emphasized how splendidly Joachim executed works such as Beethoven's Romance in G major, a slow piece of moderate technical complexity:

[First soirée, 10 December 1854] Such a highly developed virtuosity, such a touching sensual beauty of tone, as it was shown in the performance of Beethoven's G major romance, is almost never combined with such a serious striving, rejecting all superficial effect. His playing and his whole being are an object of the most general sympathy and love. It remains to be regretted, however, that such a force has so little space to expand. Since Joachim spurns everything that has not emerged from a higher artistic point of view, frequent contact with the public is made more difficult for him. He himself would perhaps be less averse to intercourse with the outside world and public appearance than he is, if a greater number of his worthy works were at his command. It cannot be denied that a tendency to loneliness is easily associated with this serious direction.Footnote 76

Joachim's choice of a romance raised this critic's concern that there were not enough worthy works for Joachim to perform. In fearing that Joachim's selective, discriminating programming would isolate him, the critic did not realize that such programming had an ‘educating’ component geared precisely towards distancing audiences from their customary expectation for mainstream virtuoso fare. Yet another reviewer of the same concert wrote:

Mr. Joachim has chosen the well-known G major romance of Beethoven and Bach's famous ciaconne …. The most delicate fragrance and melting of colours characterized one, pithy strength and masterful characteristics the other.Footnote 77

Beethoven's Romance in G major was not a typical ‘solo’, but this may have been precisely why Joachim programmed it so frequently. In comparison to a performance of a Paganinian piece with heightened violinistic demands such as outwardly effectual bow techniques – in which critics would not have highlighted nuances of sound and timbre but would have been puzzled by such diverse technical demands – romances allowed critics to focus on subtleties of interpretation, such as timbre and dynamics. Critics would have an opportunity to focus on – and highlight – Joachim's polished and refined mastery. Thus, Joachim trained critics and audiences to listen to greater nuance, here ‘the most delicate fragrance and melting of colours’.

On 21 December 1854 a concert at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig led to a label for Joachim's art which I have used throughout this article: ‘shape-oriented virtuosity’, a virtuosity that emphasizes nuanced and detailed phrasing.

The age of virtuosity has faded – that has now become a current expression; we have stopped admiring the mere keyboard virtuosos and rewarding brilliant passages with gifts of honour; in a word, audiences are done with dexterity. In this sense, then, virtuosity is in fact at an end, but that virtuosity which we would like to call shape-oriented [virtuosity], that is, which makes it its task to illustrate to us the characteristic moments within the works of our good masters … has lost none of its fullest justification. And who did not count Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim among the noblest representatives of this movement? … The two shining stars of the programme were Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata and his Romance.Footnote 78

This review remarkably mentions Beethoven's Romance in G major as one of two ‘shining stars’ that night, the other being the Kreutzer Sonata, a radically different work far greater in dimension and technical complexity. Joachim was linked with ‘shape-oriented virtuosity’ precisely because he was able, like Clara Schumann, to illustrate ‘characteristic moments in the music’, thus interpreting it in understandable terms, an achievement far more worthy for the reviewer than ‘brilliant passage-work’ and standard ‘Virtuosentum’. Other critics down the road who discussed Joachim's and Schumann's performance of the Kreutzer Sonata and the Romance in G major could not pinpoint exactly what made the performance successful but noted nevertheless the ‘most wonderful effect’.Footnote 79

Performing Beethoven's romances allowed Joachim to highlight his warm, soulful tone, which, unusually enough, had the power to ‘give rise’ to the wildest applause even in slow passages such as cantilenas. How could the performance of a Beethoven romance elicit such a passionate audience response? This review of the first of three soirées with Clara Schumann at the Berlin Singakademie is revealing:

[T]he simplest cantilena gave rise to the wildest applause; every note played by his hand breathes the soul, the deepest inwardness and truth, and takes the listener unnoticed into the realm of ideals; Joachim himself is the ideal of a violin player, perfect and consummate in every respect, who never makes concessions to the audience or wants to shine outwardly, he is the purest interpreter of our masters’ works of art. The same must be said about Clara Schumann's piano playing; for her, virtuosity is only a means, not an end.Footnote 80

Despite the elevated language and philosophical terminology (‘ideal’), this review underscores Joachim's didactic programming: ‘never making concessions to the audience’ was exactly what Joachim demanded.Footnote 81 Noteworthy, indeed, is that slow ‘cantilenas’ could provoke from 1850s audiences the type of response previously elicited with the ‘Bravourstück’. The reviewer added that Clara Schumann, likewise, used her ‘virtuosity’ as a means and not as an end in itself. Other similarly enthusiastic reviews of Joachim's performances of romances surfaced between 1848 and 1865.Footnote 82 Among other things, those were reviews of Joachim's performance of Berlioz's above-mentioned Romance tendresse et caprice.

One reviewer said that Joachim performed Berlioz's piece ‘like a young master, three times master of his art’, a high praise considering the trifle-like reputation of the genre.Footnote 83 Similarly, a reviewer of Joachim's performance of said romance in Hanover on 1 April 1854, under the baton of Berlioz himself, remarked: ‘[Joachim played] a romance and, in turn, tore the audience into a real frenzy’.Footnote 84 This romance by Berlioz imposes greater violin technical demands than Beethoven's romances. Joachim must have found it uniquely French, and, evidently, performed it masterfully and with real conviction. We will now consider another aspect, namely, the intersection of composition and performance in Joachim's Romance Op. 11 in G major.

‘Shape-oriented virtuosity’ in Joachim's Hungarian Concerto Romance, Op. 11

Listeners and critics heard simplicity in Joachim's ‘Hungarian’ Romance Op. 11 in G major, which allows us to return once more to Cheng's point about the romance genre's simplicity. Cheng's observation that romances were viewed as ‘simple’ and that they sometimes concealed ‘just how much work went into making a tune sound simple’, can be transferred to Joachim's performance and composition of a particular romance, which concealed just how much idiomatic passagework it actually contained.

‘The second movement [of Joachim's Op. 11]’, one critic argued, ‘is of extremely simple structure’.Footnote 85 This critic perceived a simplicity of means, where, at second glance, there was actually an intriguing multi-layered form with potential for generic intermixture. In order to replace the violin Bravourstück with simplicity – a key element of the romance proper – the composer needed to construct or fabricate such simplicity. How did Joachim respond to this challenge?

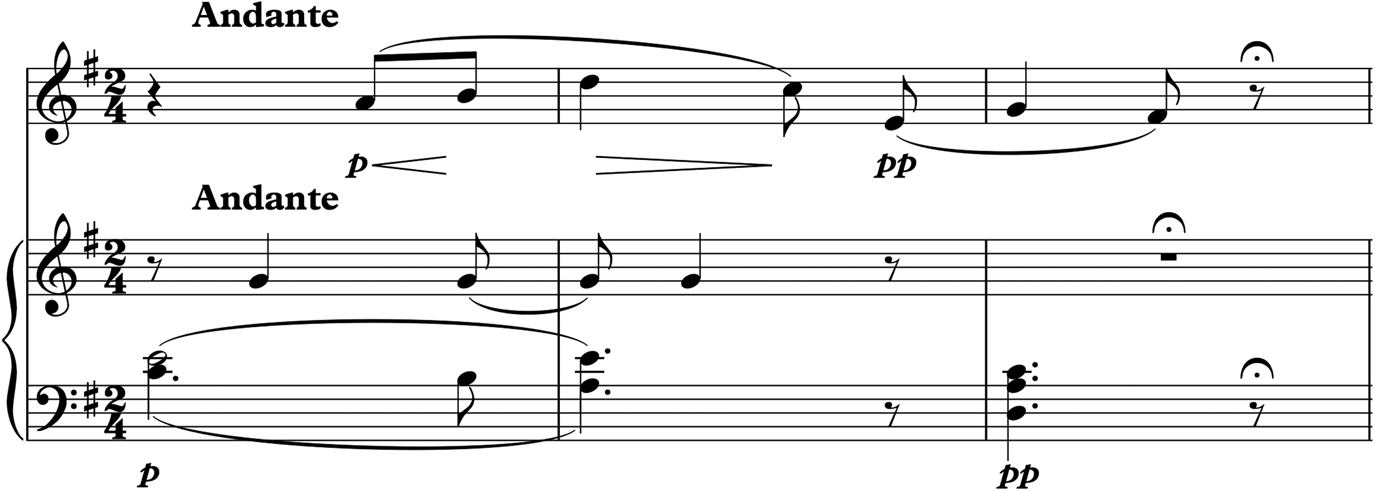

The romance begins with a question, a recitative-like phrase that precedes the romance theme proper and emerges out of a C-major triad only to come to a halt on a dominant-seventh chord of G major (built on D), followed by a fermata (Ex. 7).

Ex. 7 Joachim, Romance in G major (bars 1–3)

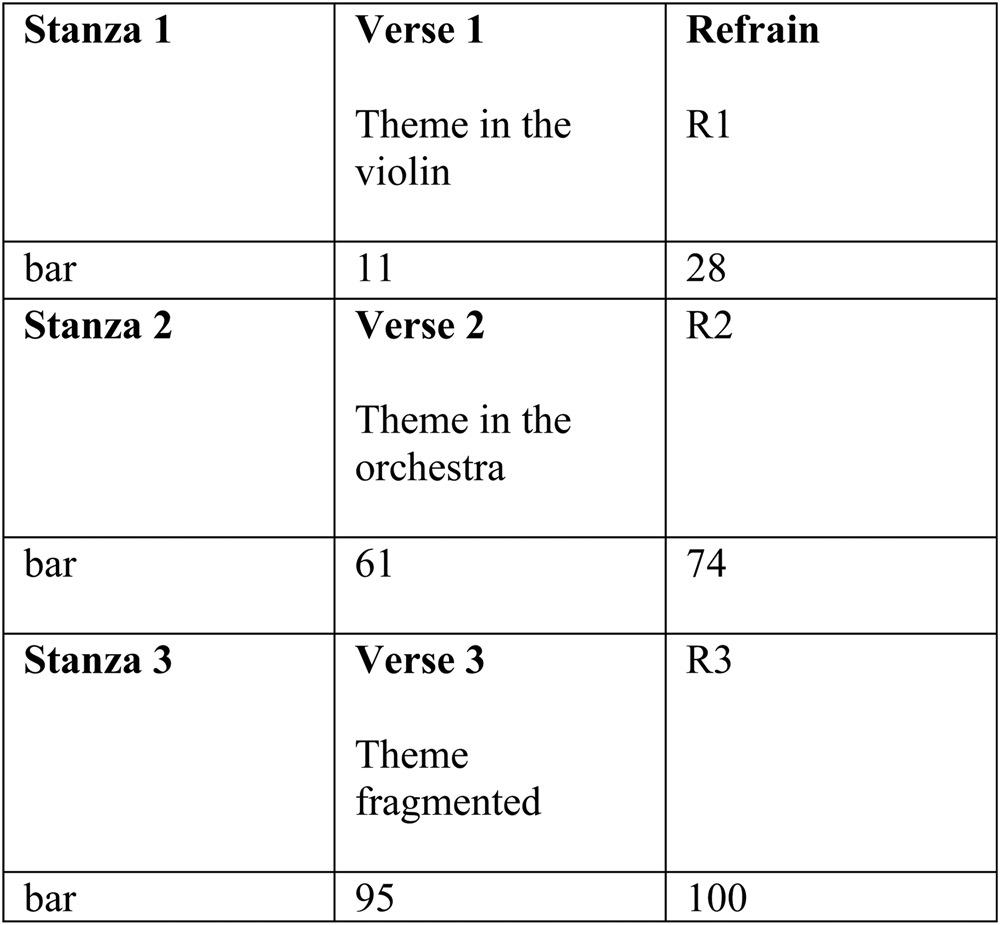

What follows is a melodic romance theme, spiced with ascending tritones (the pitches A♯ and C in bar 11 were viewed by one writer as creating ‘harmonic harshness’) and Hungarian two-bar cadential endings (‘tail’). The theme unfolds in eight bars; the second four are repeated. As in Op. 2, which preserved the century-old minore tradition for the B section, Joachim's Hungarian romance contrasts its clear-cut A section with a minore B section featuring a stubborn theme in E minor and tonic–dominant sequences typical of the style hongrois. Although not lacking a certain ‘punch-line’ quality – a quality Hepokoski associated with the French couplets form, which is discussed in more detail belowFootnote 86 – the E-minor theme was viewed by one writer as somehow deficient. The minore gives way to the opening theme, ornamented in the fashion of Beethoven's secondary theme in the first movement of Op. 61 (‘graciously ornamented by the solo’Footnote 87). If the romance had ended here, it would have fallen neatly into a ABA′ ternary form, but it continues. As the Deutsche Musikzeitung described, Joachim added two more parts: [1] ‘then towards the end a più moto, and [2] the solo part once again suggesting the theme, as if to say goodbye’.Footnote 88 The result is a five-part form (Fig. 2). Curiously, Joachim separated the ABA′ ternary from its outer frame via double bars.

Fig. 2. Joachim, Romance in G major, formal diagram

We know from Abendglocken Op. 5 that Joachim used the thin double bar intentionally and with care, preferably as a framing device. Here they seem to bookend an ABA′ form – a nod to the old romance tradition. But how do we make sense of the opening cadenza-like bars and of the sections following the thin double bar?

When Joachim composed his Hungarian romance (c. 1857) he may have contemplated other romances he had performed within the last three years, such as Berlioz's Romance tendresse et caprice. In Berlioz's romance, the recitative-like beginning gives way to a French verse–refrain stanza. Applying Hepokoski's definition of the French couplet, a type of stanza, to Berlioz's romance, we discover two stanzas, each of which comprises a ‘preparatory first part’ of the romance theme (bars 11–41) that repeats and ‘ends with a connecting link’ (bars 42ff., preparing us for ‘the more emphatic, concluding “punch-line” refrain’ (bars 60 ff.). Perhaps most conspicuous about Berlioz's and Joachim's romances are the similar tempo changes and double bars (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Berlioz, Rêverie et Caprice (Romance tendresse et caprice [1854])

Berlioz intensifies the piece by increasing the tempo within each stanza, ending each with Allegro and Allegro vivace, respectively. The lyrical first part of the melody is connected to a more ‘punch-line’-like refrain, which in Berlioz's example is faster and more energetic. Neither the melodic Adagio sections nor the ‘connecting linking’ sections are unambiguous due to the recitative-like ad libitum sections in which fermatas and undisciplined phrases prevail. The mood, however, is clear enough: ‘sentimental, even pathetic’, which, according to Rodgers, ‘explains its designation romance’ in its original title.

Joachim's middle section in E minor was misunderstood by some reviewers. One found it not to be ‘significant enough at all’: ‘the middle section in e minor pleases us less than the opening theme. The melodies in it are not on a par with those of the main theme, and are not significant enough at all’.Footnote 89 But they are energetic, similar to Berlioz's ‘refrain’, and could be viewed as a ‘refrain’ in Joachim's G major Romance, given its many returns throughout the movement, often in fragments, and yet unmistakably recognizable due to its head-motive (Ex. 8).

Ex. 8 Joachim, Romance in G major (bars 27–28)

Beyond appearing in the opening of the B section, the head-motive emerges after the orchestral theme A′ (ornamented by the violin), and right after the last glimpse of the main theme, the A″ section (bar 95), which one critic referred to as ‘merely a glimpse, as if saying farewell’ (Fig. 4).Footnote 90

Fig. 4 Joachim, Romance in G major, strophic form in the ‘French manner’ with B-section theme acting as ‘refrain’.]

According to this view of Romance in G as containing a ‘refrain’, and following Hepokoski's verse–refrain model in the ‘French manner’, we could divide the romance into three stanzas, each subdividing ‘into two parts’. Beginning with the main theme that acts as the verse and features ‘repeated phrases’, all three ‘verses’ are followed by a second part, the concluding the ‘punch-line’ refrain. Joachim seems to have remembered not only Beethoven's two romances but also Berlioz's Romance tendresse et caprice, thereby adding himself to the list of composers for whom the romance genre presented a welcome opportunity for generic mixture between the salon and the (orchestral) stage.

Joachim's Romance in G major: Performing Simplicity

Considering the romance from a performative angle, the question arises how a virtuoso composer could reconcile the genre's mandated ‘simplicity’ with the desire to compose something challenging and satisfying enough for someone with a supreme level of skill. One possibility would be to compose something that sounds ‘simple’ yet presents complex, technical demands.

According to Hans von Bülow, only a virtuoso of the modern, transformed variety could execute well the difficulties of works by J.S. Bach (for Bülow, nothing less than the veritable ‘Zukunftsmusik’ and a measuring stick of true skill and technique). To this end, the general advances of violin technique during the Golden Age of the 1830s and 40s were not superfluous: as will be shown, the Romance in G major, although seemingly aiming at an aesthetic of simplicity, by no means was simple from the perspective of the technical and artistic skill. Just as ‘virtuosity's meaning is constructed and not posed, a meaning that arises from “the relations between the internal structure of works and the reactions of the listeners”’,Footnote 91 so too is performative meaning constructed. Whereas Paganini and Liszt exploited the ‘demonic’ type, which resonated well with early-to-mid nineteenth-century audiences,Footnote 92 by the mid-1850s, Joachim was posing in his persona as priest or Geigerkönig. That the romance genre helped Joachim anchor this persona to the collective subconscious of the world of violin playing may seem counterintuitive, but shall become clear in what follows.

To create in the romance a sense of calm, dignity and, above all, simplicity, Joachim found it necessary to use violin-technical idioms diametrically opposed to those of the Bravourstück (the latter typically includes sautillé, ricochet, staccato, and passages requiring great physical investment and energy), namely, smooth legato runs with few bow changes, which require the actions of the bow-arm and body to be kept to a minimum and only involve small-scale finger- and hand-movements in the left hand. In addition, bow changes could be executed not on the beat, when they are conspicuously registered aurally and visually as movements or gestures, but after the beat to avoid unnecessary physical commotion and create an illusion that the bow never needed to change direction. Such a still approach suggested to listeners that ‘simplicity’ characterized this romance, the ‘easiest’ of all genres.

Joachim's ‘performed’ virtuosity in this romance differs from his approach in the 1840s. To provide a counter example: the Hungarian Fantasy, written between 1846 and 1850 at the height of the Golden Age of virtuosity, frequently exploited noisy, attention-gathering, 1840s-types of bow strokes, which foregrounded bow-activity; it was replete with noise from the bow hitting the string (ricochet), noise from the bow being pushed with many stops either in an up- or down-bow (staccato), and fast bow-strokes played on the string with separate small bows but at such high speed that the bow lifts off by itself (sautillé). Such fireworks were popular during the 1840s but lost much of their appeal around 1848. How Joachim constructed a type of virtuosity that was less explicit and involved less body movement, but by no means simple to play, is the topic of this final section.

Two tools in particular helped Joachim meet the challenge of ‘performing simplicity’. First, in the second appearance of the main theme (the A′ of the ABA′CA″ design), he placed the theme in the orchestra while the violin ornamented the theme. By itself seemingly unassuming, this approach appropriated Beethoven's ornamentation to a level perhaps unmatched in the romance genre, requiring the violin to play abundant hemidemisemiquaver sextuplets and octuplets and creating extremely long legato slurs as a result (Ex. 9).

Ex. 9 Joachim, Romance in G major, piano reduction (bars 65–76)

All that said, Joachim hid the violin's filigree behind the main theme heard in the orchestra. Perhaps he had the secondary theme of the first movement of Beethoven's violin concerto in mind (bars 152ff.). But the difference is that Beethoven restrained the melodic diminutions to quaver triplets and semiquavers. Executing Joachim's ornamental garlands, curiously, does not take much effort from the bow at all, except for having to draw it very slowly and smoothly, in order not to run out of bow and to guarantee smooth string crossings.

To maximize the smoothness of the bow, Joachim had one more tool up his sleeve: concealing bow-direction changes by placing them off the beat, thus making them minimally audible (bars 67–71, 74–75). Concealing bow changes is widespread in Joachim's mature violin works, including his second (Hungarian) and third concerti in G major (1864), mature cadenzas, Notturno (1858), and Variationen für Violine mit Orchesterbegleitung (1879). Although a subtle device, it helped create the impression of physical stillness as the right arm moves quite deliberately, so that fast movements occur only in the small-level finger activities of the left hand. While Joachim's ‘legato virtuosity’, which required considerable technical demands on the violinists, has drawn attention before, how it helped him construct a type of ‘performative simplicity’ appropriate for the romance has largely evaded attention.

As Bülow had foreshadowed, Joachim synthesized traditions of the romance that assimilated not only the French Conservatoire influences, but possibly also his performative experience under Berlioz's baton, resulting in Joachim's G major romance in a greater tempo diversity and more expressive freedom before and after the double bars. Although Joachim surely was not responsible for having brought about a shift in how violin romances were composed, the type of violin idiom he advocated in the G-major romance matched how composers would approach the genre subsequently, from Max Bruch (1874) to Antonín Dvořák (1879), and from Johan Svendsen (1881) and Gabriel Fauré (1883) to Jean Sibelius (1904/1915–17). Like Joachim, they privileged melody and an omnipresent sense of calm air, an application of smooth, non-angular bowing, and a willingness to explore the horizon behind genre boundaries.

While this article has focused largely on Joachim's romances – and therefore has not proven that these pieces changed the violin romance genre as a whole – the author hopes to have provided evidence that the violin romance played a significant role in a larger development with which Joachim, the violinist-composer and long-term director of the Berlin Hochschule from 1869 until his death, is deeply linked: the Werktreue movement,Footnote 93 which he supported tirelessly via his dedication to the ‘classics’, that is, works by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Spohr, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, and a few others. While Joachim's advocacy for Werktreue has been the topic of discussion for more than ten years, this article highlighted how a small and unpretentious genre such as the romance helped Joachim achieve his aesthetic goals at a time when violin virtuosos were prone to be pushed into the Virtuosentum corner.