The turn of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of new genres of salon music, together with new types of both salon musicians and audience members. Attention has been given recently to such areas as the role of women composers and performers in the elevation of the Lied as a musical genre; salon performance practices; the contribution of women musicians to piano music in the salon context; and the intersections between salon music and literature.Footnote 1 The importance of music for the education of young girls in the late eighteenth century is also well-documented. The British writer Elizabeth Lachlan (née Appleton) (1790–1849) remarked on the importance of music to a girl's education and upbringing: ‘I know not of any gentleman's or nobleman's daughter who has not attempted, at one period in her life, to learn music. So general a pursuit requires, and so elegant an accomplishment demands, our particular attention’.Footnote 2 Less discussed, but of demonstrable significance, has been the appearance of the tambourine in the late eighteenth century and the extent to which it created a platform for women to contribute to domestic and salon music in more elaborate, virtuosic ways than had been customary. In this article I consider extant tambourine instruction manuals and compositions dating from the turn of the nineteenth century, that reveal a variety of techniques reflecting ‘feminine’ qualities such as gracefulness and elegance, while also hinting at virtuosity and individualism. Through this discussion I demonstrate the ways in which the short-lived fashion for the tambourine in the British salon reflects a shift in attitudes towards social customs. In particular, it allowed women the opportunity to move away from the conventional idea that their music making should confine itself to ‘stationary’ instruments such as the piano or harp. The tambourine, albeit modestly, offered women greater creative opportunities in the early nineteenth-century salon in the period before such opportunities were surpassed by the arrival of new, revolutionary genres, most notably the Schubertian Lied.

The tambourine had held an association with women and dancing since Biblical times: as James Blades observed, it is one of the few percussion instruments to have remained relatively unchanged over a long period of time.Footnote 3 This association can be seen in a variety of contexts. The book of Exodus describes how ‘Miriam the Prophet, Aaron's sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women followed her, with timbrels and dancing’, while in ancient Egypt female temple dancers would beat tambourines during religious ceremonies, including funeral processions.Footnote 4 In the wake of this historically close relationship with dance, eighteenth-century artists frequently represented the tambourine as a feminine instrument, perhaps as a reflection of the graceful elegance that was expected of gentrified girls at this time. Richard Leppert noted that the feminine representations of the tambourine in the eighteenth century stand in stark contrast to paintings of boys and drums, in which the expectation that boys should serve their king and country, putting the collective good ahead of their own safety or gain, is implied.Footnote 5 Philippe Mercier's undated portrait of A Young Drummer Boy (Fig. 1) shows the boy's intention to carry out his duty even if he is too young or too small to fight, while the stance, his gaze, his three-cornered hat and neat attire, and his adept holding of the sticks, all suggest that he is in command. Jean-Étienne Liotard's painting Femme au tambourin vêtue à la turque (c. 1738–1743) provides an intriguing example of the feminine association with the tambourine in the same period (Fig. 2): here the pale complexion of the woman forms a striking counterpoint to the rich, exotic costume and the tambourine.Footnote 6 The instrument was also, on occasion, represented by artists as a gimmick or toy used by young girls: a 1792 print by Francesco Bartolozzi (1727–1815) of the three youngest daughters of King George III shows Princess Mary holding a small, colourful toy tambourine above her head.Footnote 7

Fig. 1 Philippe Mercier (c. 1689–1760), A Young Drummer Boy, early eighteenth century (© L.R. Nightingale: Norwich, Norfolk)

Fig. 2 Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), Femme au tambourin vêtue à la turque, c. 1738–1743 (© Musée d'art et d'histoire, Geneva, 1938–0008)

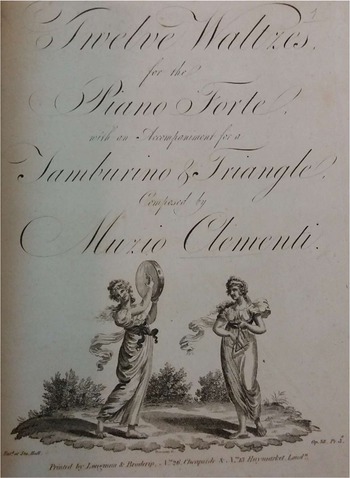

By the final decade of the eighteenth century the tambourine ceased to be used solely as a way of reflecting female gracefulness in art and became a popular instrument for young girls to learn, as indicated by the existence of at least three tambourine instruction manuals sold by London-based music publishers from their shops: those of Joseph Dale, Thomas Bolton and Thomas Preston.Footnote 8 All three manuals describe a variety of different shakes, rolls, jingles and turns (of the instrument and of the body) that an accomplished tambourine player could have included in performances. As well as the publication of instruction manuals, the popularity of the instrument can be seen through Dale's manufacturing of patent tambourines that were made with ‘a new method of straining or tightening the skin … so as effectually to remove certain objections and impediments felt by the performer’.Footnote 9 The extent of the tambourine's popularity at the turn of the nineteenth century can be further demonstrated by the fact that Muzio Clementi, a well-established composer and teacher in London, chose to use an edition of his Waltzes Op. 39 for piano, tambourine and triangle to launch his publishing career. Evidently, he took advantage of the brief fashion for the tambourine to ensure the quick commercial success of his early publications.Footnote 10

The most celebrated composer of piano pieces with parts for tambourine was Daniel Steibelt (1765–1823). Born in Berlin, Steibelt established himself as a popular piano virtuoso in Paris during the 1790s, where he produced his most successful work, the opera Roméo et Juliette (first performed at the Théâtre Feydeau on 10 September 1793). By 1797 Steibelt was a regular performer in London's salons and concert halls, giving a performance of his new Third Piano Concerto, to great acclaim, at a Salomon concert on 19 March 1798.Footnote 11 This is quite a testament to the man who is remembered today, if at all, for his humiliation at the hands of Beethoven in a piano contest arranged by Count Moritz von Fries in Vienna in 1800. During his residence in London, Steibelt married Catherine Dale (1778–1825), daughter of the composer, publisher and patent tambourine manufacturer Joseph Dale. According to Arthur Loesser, ‘she was quite an able manipulator of the tambourine, and joint performances with her husband were much enjoyed by a generation of new-formed music customers’.Footnote 12 The couple caused a great sensation when they included works for tambourine and piano in their salon performances whilst touring Europe together; in Prague this can be seen to have resulted in an interest in learning the tambourine there. The memoirs of the Bohemian musician and writer Václav Jan Tomášek record the phenomenon:

The desire to be able to handle the instrument … was lively in all the ladies, and so it happened, that Steibelt's girlfriend was happy to be available to provide instruction therein. The instruction was over in twelve hours, for which the teacher was paid with twelve gold ducats; she received the same price for a tambourine, which meant that Steibelt spent several weeks in Prague, and gradually sold a huge wagon full of tambourines.Footnote 13

The tambourines that they sold would almost certainly have been those manufactured by Catherine's father, thus providing a lucrative opportunity for Dale to establish marketing links with European music merchants and publishers, in a similar way to Clementi's relationship with Breitkopf and Härtel in Leipzig, or Pleyel's association with Dussek in Paris. A fee of 12 gold ducats was a considerable amount to charge for music lessons in central Europe at this time. Clementi, one of London's most sought-after piano teachers, reputedly raised his fees to one guinea per hour from 1784 onwards; this was roughly half the amount that Catherine Steibelt charged for a tambourine lesson in Prague. If people were willing to pay such a large amount for lessons, there was evidently status and enjoyment to be had in mastering the instrument.Footnote 14 It is likely that the piano and tambourine duets would have been included in Steibelt's salon performances as short encores or interludes, alongside more substantial works such as the Storm rondo (an adaptation of his Third Piano Concerto finale) or programmatic battle pieces such as La Grande Marche de Buonaparte en Italie.Footnote 15 Although Steibelt's works continued to be published well after his death, late nineteenth-century music critics, among them Oskar Bie and Eugène Rapin, viewed him with considerable animosity and moral condemnation, describing him inter alia as a disgraceful charlatan and the ‘main parasite of his age’.Footnote 16 Bie observed:

This Steibelt was one of the disgraces of the age. Bespattered with praise, he rushed through Europe with his trashy compositions, his battles, thunder-storms, bacchanals, which he played ad libitum, while his wife struck the tambourine in concert with him. The populace was enraptured, for Steibelt and Madame tickled their nerves with sparkling shakes and tremolos.Footnote 17

Such perceptions, which may have a kernel of truth, informed the received view of Steibelt.

Despite his piano sonatas and battle pieces, which typically showcased innovations in tremolo and pedal technique, it appears to be the works for piano and tambourine that most strongly captured the imagination of European audiences. This is apparent from Tomášek's writings:

Although Steibelt's artistic achievement did not please the Prague nobility, he yet knew how to make his reckoning with them in a different way. He had, in fact, an English woman with him, whom he introduced as his wife, and who played the tambourine, accompanying him at the pianoforte, for whom he wrote several small rondos. The new combination of such heterogeneous instruments so electrified the highborn, that they could hardly get enough of being seen on the beautiful arm of the English woman.Footnote 18

The ‘little rondos’ described by Tomášek probably refer to the many short waltzes, divertissements and bacchanals that Steibelt wrote for piano with accompaniments for tambourine. These pieces are simple in nature, typically in major keys and, in the case of the waltzes, in da capo form. There are a few exceptions to this, however, in which the composer includes hints of exoticism. For instance, some editions of his Turkish Rondo for piano, Op. 38, contain an additional part for the tambourine.Footnote 19 In similar fashion to Mozart's Rondo alla Turca from the Piano Sonata in A major, K331, this work uses many of the so-called ‘Turkish’ musical devices popularized by composers in the 1790s, most notably the duple metre, static harmony and alternating major and minor passages.Footnote 20 The tambourine part is not included in several earlier editions of this piece; possibly its use represents an afterthought on the part of the composer, in response to the popularity (and therefore marketing potential) of the instrument that developed during the late eighteenth century. Orchestral and operatic works written in the so-called alla Turca style typically feature bass drum, cymbals and triangle (with no tambourine) to represent the Turkish percussion section.Footnote 21 However, it is possible that Steibelt originally intended this work to be performed on a piano with a Janissary stop, a mechanism he may well have been familiar with given the fact that he spent time in Vienna in 1800.Footnote 22 Here the tambourine part may have functioned as a substitute for the Janissary stop (which is unlikely to have been available in many domestic households and, in any case, was exceedingly rare in Britain at this time) in order to make the work more accessible to the public. Given the tambourine's historic association with women, and the popularity of the instrument amongst young girls in late eighteenth-century Britain, the reason behind its use in this instance to represent the alla Turca style, which Mary Hunter claims is associated with ‘extreme masculinity’, is rather arcane.Footnote 23 It is also significant that few orchestral or operatic pieces that make use of a ‘Turkish’ percussion section include a part for tambourine. For the purposes of salon music, the tambourine would have been played by girls in a graceful, elegant manner (as outlined in the various instruction manuals) that bore little resemblance to the overly rhythmic and heavily accented parts found in Steibelt's Turkish Rondo (Ex. 1). These connotations may in part explain why the waltz was by far the most common musical form for which tambourine parts were written.

Ex. 1 Daniel Steibelt, Turkish Rondo, Op. 38, bars 7–13 (London: R. Birchall, c1800)

Throughout the A sections of waltzes written for this combination of instruments, the tambourine would typically reinforce the rhythmic substrata of the right-hand piano part, and thus offer primarily an accompaniment that used techniques (as discussed by Thomas Preston) known as flamps and semi flamps (see Ex. 2).Footnote 24 The piano part would generally change character in the B section, replicated by the tambourine playing longer held notes using techniques termed gingle notes or bass notes – these would be achieved by moving the thumb or index finger across the skin of the instrument in order to create a continuous jingle sound.Footnote 25 Dale's Waltz Op. 16 No. 13, ‘Vivace alla Scozzese’, demonstrates an overwhelming use of bass notes in the tambourine part (Ex. 3), perhaps to resemble Scottish military drumming (also displayed in the prominence of the Lombard rhythm in the piano part).Footnote 26

Ex. 2 Flamps (marked ‘a’) and semi flamps (marked ‘b’) in Steibelt's Bacchanal No. 1 (Paris: Chez Melles Erard, c. 1800)

Ex. 3 Dale's Waltz Op. 16 No. 13 in Eight Waltzes for the Pianoforte or Harp with an Accompaniment for Flute, Tambourine and Triangle (London: Dale, 1800)

Whilst flamps, semi flamps, gingle notes and bass notes were the most common techniques found in such waltzes, other more elaborate techniques such as the double travale were also used. This was essentially a short flourish which involved a quick turn of the wrist to be correctly executed. Thomas Bolton's instruction manual indicates that the second note is produced with the fingers forming a cluster, and the third is described as an up-hand, thus creating three distinct sounds. He warns that ‘in the performance of the foregoing characters it is necessary to observe that much depends on the pliantness of the wrist’.Footnote 27 An example of the double travale can be found in the music of Joseph Mazzinghi (1765–1844), composer of several comic operas performed in Covent Garden at the turn of the nineteenth century (Ex. 4).Footnote 28

Ex. 4 Double travale (a) and gingle notes (b) in Joseph Mazzinghi's ‘Air No. 4’ from Twelve Airs for the Pianoforte with Accompaniments for Flute and Tambourine (London: Goulding, Phipps and D'Almaine)

Although Steibelt's encores clearly caused a stir in many of Prague's salons, printed publications of such works were primarily intended for the British domestic market; surviving collections of music manuscripts in aristocratic properties such as Tatton Park and Oulton Park, Cheshire, illustrate this trend.Footnote 29 The reasons for the popularity of these waltzes amongst girls and, indeed, their more general social acceptance, can perhaps be traced to the calls for a shift in gender values from such pioneering writers as Mary Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay and Mary Hays, whose work came to prominence in the aftermath of the French Revolution. In her Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), Wollstonecraft brought issues such as the social class system and perceptions of female identity into question, heavily criticizing Edmund Burke for his pessimistic, regressive view of the French Revolution: she accused him of reverencing the ‘rust of antiquity’. Wollstonecraft pushed women's rights to the forefront of British politics for the first time.Footnote 30 She fundamentally believed that events in France could act as a catalyst for social reform, removing outdated attitudes. George Taylor has noted that her ideas were beginning to take hold: the historical events of the 1790s allowed gender roles to become politicized, so that qualities such as ‘directness and simplicity’ became more desirable and acceptable characteristics of women than they had been a decade earlier.Footnote 31

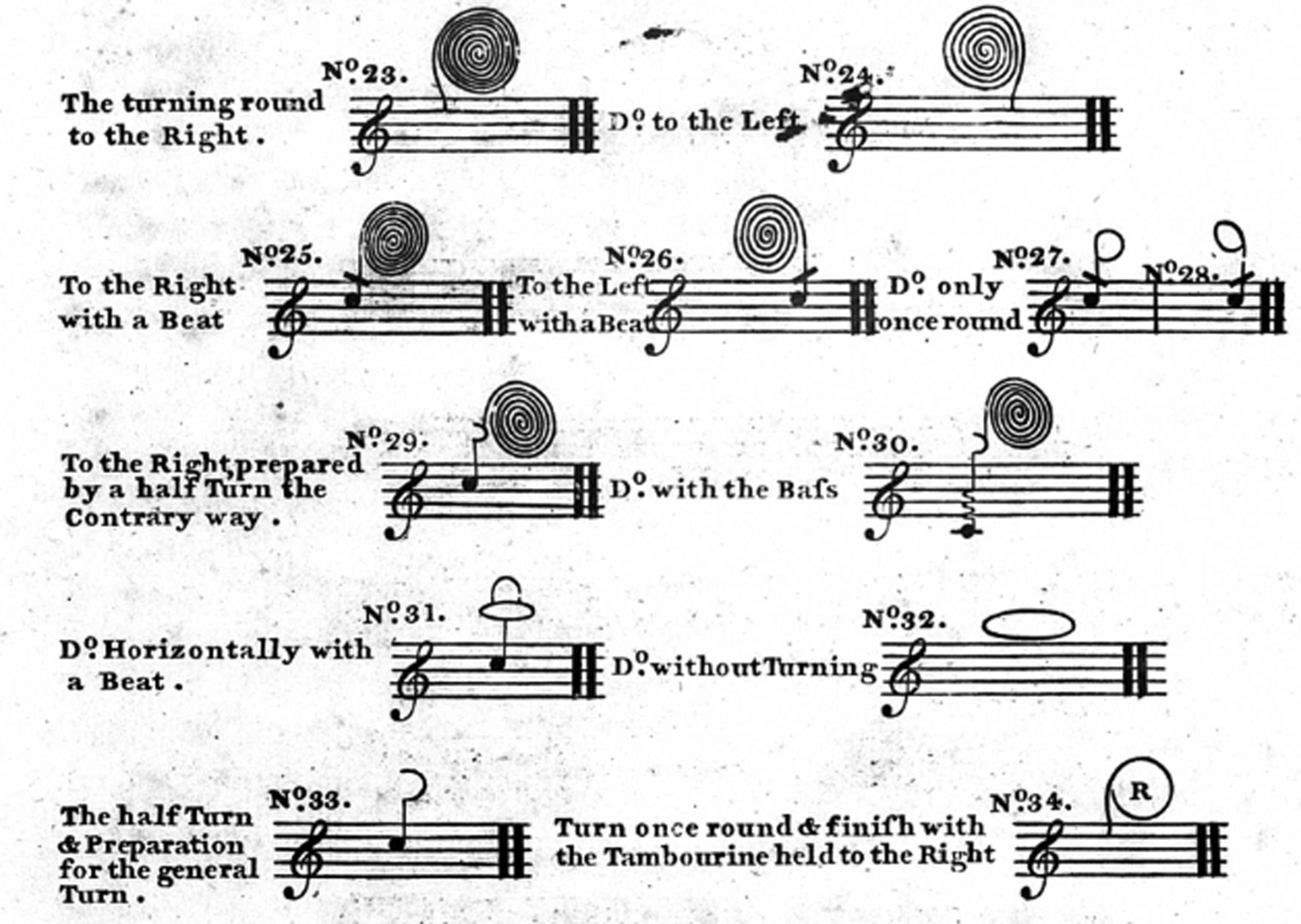

In several respects, the appearance of the tambourine in the home and in private salons reflected the changing values that proponents of women's rights were advocating. Many of the 34 techniques listed in Dale's instruction manual are sufficiently passive to portray the graceful young girl as a desirable character, yet are still able to create enough expressive interest to offer perceptible contrast with other domestic musical practices. Dale is careful to advise performers as to the ways to play the instrument without creating a notably flamboyant spectacle: ‘if [it is] held properly you will be able to move [the tambourine] up or down and from side to side, or in any manner required without being obliged to grasp it.’Footnote 32 He goes on to declare that ‘the necessary practice’ of playing the instrument ‘at first must simply be up and down, with the wrist out, and the elbow even with the hand, the arm to be kept as still as possible and the tambourine turned a little from you’.Footnote 33 Unlike the repertoire for other instruments of the period that were deemed unsuitable for girls to play, particularly the violin, tambourine parts written by Steibelt, Clementi and Dale, amongst others, provided a middle ground between virtuosity and the concept of gracefulness seen as a necessary quality of upper- and middle-class girls in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 34

In his 1757 essay A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Edmund Burke described gracefulness as ‘an idea belonging to posture and motion’ and explained that achieving it required the avoidance of appearing ‘divided by sharp and sudden angles’.Footnote 35 Eric McKee takes the case of Mozart's ballroom trios, written for the festivities at the Redoutensaal, Vienna, between 1788 and 1791, as exemplifying the various attributes of grace: ‘simplicity (tempered with variety)’, ‘composure of the body’, ‘roundness of motion’, ‘weightlessness’, ‘restraint’, and ‘hidden control’.Footnote 36 These attributes can also be found in abundance in tambourine works of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The tambourine's appearance in the private salon not only satisfied the ideals of stillness, composure and passivity that were expected whenever women played musical instruments (this can also be seen in artistic representations such as Fig. 2), but additionally offered greater variety, giving the performer a sense of individualism. It was perhaps that new-found individualism that the Prague audiences regarded as the most intriguing aspect of Catherine Steibelt's tambourine playing.

The simple rhythmic structure characteristic of the tambourine parts, coupled with the wide range of techniques (for instance, the rapid alternations between flamps and semi flamps seen in Steibelt's Bacchanal No. 1) created an opportunity for girls to find a suitable balance between virtuosity and discipline. Bolton's request for the turn to be effected ‘with the most careless elegance and ease’, and the lightweight nature of Dale's patent instrument, indicate a sense of conforming to Burke's concept of passive gracefulness; yet certain elements of the musical notation and instruction manuals hint at the performer's less restrictive role – one that instead emphasizes movement and even extravagance.Footnote 37 Following a detailed study of the musical collections of the Egerton family at Tatton Park, Katrina Faulds proposes that the theatrical nature of the tambourine, as seen in extant iconography, instruction manuals and these short waltzes, allowed for a new choreography to be centred on the tambourine player, giving women an opportunity to express themselves in ways contrary to contemporary literature on social conduct.Footnote 38 Nowhere are these ideas better demonstrated than in Joseph Dale's Grand Sonata Op. 18, written for piano and tambourine with accompanying parts for flute, violin and basso.

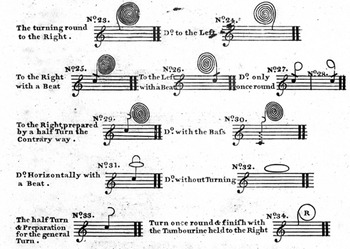

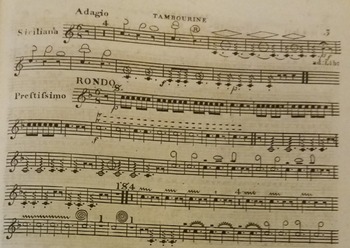

Dale's Grand Sonata is highly significant in the context of this study as it displays the new tambourine choreography more fully than any other extant work from the period; furthermore, it suggests a more serious musical role for the tambourine than that seen in Steibelt's short waltzes. Its most notable choreographic feature was known as a turn. Dale's instruction manual describes numerous types of turn, including ‘turning the tambourine round upon the thumb to the right (or left) as many times as you can’, or holding ‘the tambourine above your head horizontally with its [the instrument's] head downwards and turning it round, taking care to stop in the same position’.Footnote 39 Dale implies that there were as many as 11 turns with which a tambourine player might be familiar (Fig. 3). The range of techniques and movements shown here gives us some idea of how Catherine Steibelt played the instrument in the Prague salons and elsewhere.

Fig. 3 Different types of turn in Dale's Instructions for the Tambourine (London: Dale, 1799)

The title page of this work reveals that the tambourine parts were in fact written by Dale's son, Joseph Dale Junior; it was dedicated to the Duchess of Dorset, presumably Arabella Diana Cope (1769–1825).Footnote 40 The piece itself was most probably intended for private salon performances in aristocratic residences; only the piano and tambourine have an obbligato role. Presumably the flute, violin and basso parts could be included according to availability of personnel, and were almost certainly written with the male household members in mind.Footnote 41 The work is structured in three movements: an allegro, a siciliana and a rondo.

The opening of the first movement has the tambourine function as a concertante instrument, with the piano, flute, violin and basso playing a 30-bar introduction prior to the entry of the tambourine, which plays almost continuously thereafter. Staccato beats, double travales and short bass notes dominate the early stages of the movement. In bars 64–66 we see an alternating sequence of gingle notes that are to be played by the index finger and thumb respectively (Ex. 5). The expectation here was that on beats one and two the performer would move her index finger around the edge of the tambourine in an anti-clockwise direction, pressing in order to make it jingle, and then returning the opposite way with the thumb on beats three and four. The ending of each phrase is marked with a turn, usually to the right of the body (marked as No. 23 in Dale's instructions – see Fig. 3). Here, Dale specifies that the performer is to ‘turn the tambourine round upon the thumb to the right as many times as you can and as the time will admit’.Footnote 42 This technique, one that unsurprisingly never found its way into orchestral music, again highlights the theatrical and visual nature of these works. Techniques such as this would most likely have had greatest impact if executed while holding the tambourine high in the air. Extant iconography seems to support this: the title pages of many volumes with tambourine parts show a female tambourine player holding the instrument above head height (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Title page of Clementi's Op. 38 waltzes for piano, tambourine and triangle (London: Clementi & Co., 1802)

Fig. 5 Elaborate tambourine instructions in Preston's Instructions for the Tambourine (London: Preston, 1813)

Fig. 6 Elaborate tambourine instructions in Bolton's Instructions for the Tambourine (London: Bolton, 1799)

Ex. 5 Gingles with the index finger (a) followed by the thumb (b) in Dale's Grand Sonata, first movement, bars 64–66

In the second movement, a siciliana, it is clear that choreography is the main dramatic agent of the tambourine part, rather than any specific instrumental technique or sound. Here the composer specifies that the turn of the tambourine should occur only once (see Fig. 3, No. 27), or not at all, or that the instrument should be held horizontally above the head and turned once, stopping in the same position. Considering the typically slow speed of a siciliana, the performer would have required a strong sense of rhythm and pulse to ensure that the choreography matched the speed of the other instruments. Later in the movement the player is expected to perform a round bass (a technique that Dale suggests needs to be taught by a master in order to be fully understood). Again highly visual in nature, this involved the performer turning the tambourine towards herself, passing it under the arm, whilst continuing to play a bass note.

In similar vein to that of the first movement, the tambourine part of the rondo finale largely consists of flamps (also known as beats) and bass notes, with occasional round basses and right- or left-hand turns. The final passage of the movement contains symbols above certain notes that indicate which part of the finger the performer was expected to use (Ex. 6).

Ex. 6 Different types of beat in Dale's Grand Sonata, third movement, bars 108–110

Dale specifies that the following technique should be adhered to when playing this passage (Ex. 7):

The beat at no. 9 is done by striking downwards with the nails of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd fingers together. That at no. 10 by the tops of the same fingers on the left side of the tambourine. That at no. 11 by the back fingers on the right side, and that at no. 12 with the ends of the fingers on the inside of the tambourine.Footnote 43

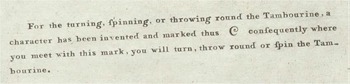

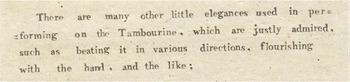

Clearly, in addition to the choreographic turns, the performer was expected to possess considerable dexterity in order to be able to play this work effectively. Furthermore, the part would need to be memorized because the choreography would make reading the music from the score or part impractical. The elaborate techniques and choreographic turns outlined in the instruction manuals and replicated in Dale's Grand Sonata hardly display the attributes of female gracefulness that are visualized in mid-eighteenth-century artwork (see Fig. 2) and described in the writings of Burke. Descriptions of tambourine techniques in all of the extant instruction manuals, among them ‘turning, spinning or throwing round the tambourine’ (Fig. 5) or ‘beating it in various directions, flourishing with the hand, and the like’ (Fig. 6), support the view that a new role for the female performer in private salons was being formed that went further than contemporary social customs would allow. Faulds describes how such works enabled the tambourine to leap ‘from the stage to the music room and, in its very theatricality, threatened established notions of genteel female comportment’.Footnote 44 The considerable variety of turns, jingles and bass notes seen in the second and third movements of Dale's Grand Sonata represent a shift away from stillness and restraint, towards virtuosity and individual expression (Ex. 8).

Ex. 7 Further examples of beats in Dale's Instructions for the Tambourine

Ex. 8 Tambourine part in Dale's Grand Sonata, second movement, bars 1–16, and third movement, bars 1–73 (London: Dale, 1800)

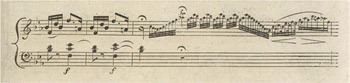

This close-knit relationship between dance and the tambourine is apparent in Steibelt's adapted version of his ballet La Retour du Zephyr for piano, violin and tambourine.Footnote 45 An 1819 obituary in The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review states that La Retour du Zephyr was originally composed as a one-act ballet when Steibelt was living in Paris, where it was successfully premiered at the Opéra on 3 March 1802.Footnote 46 The ballet was Steibelt's last major work before returning to London; he possibly sensed an opportunity to adapt the work for a smaller, private salon ensemble in order to appeal to a broader sphere of customers and re-establish himself on the London musical scene after a four-year absence.Footnote 47 From the evidence of extant parts housed in the British Library, the tambourine features only in the last three movements, though it is possible that the instrument appeared in all six movements in other editions of the same work now lost.Footnote 48 However, the abundance of slurs in the piano part compared to the rest of the work, as well as the grazioso (first and second movement) and adagio (third movement) tempo markings, suggest that the tambourine may have been deemed inappropriate in the earlier movements. Furthermore, the numerous cadenza-like passages in the second movement (Ex. 9) probably indicate that Steibelt intended to make the pianoforte part the focal point of the movement, and any additional tambourine parts would have been an unnecessary distraction.

Ex. 9 Cadenza-like writing in the pianoforte part of Steibelt's arrangement of La Retour du Zephyr, second movement, bars 86–88

The final three movements of the arrangement are far more akin to the short rondos, waltzes and bacchanals that the Steibelts would have played in Prague. The fourth movement, a waltz, is structured in ternary form; unlike the majority of Steibelt's earlier waltzes it begins in a minor key (D minor), with the B section in the tonic major. In the A section the tambourine part tends to follow the rhythm of the piano melody, and largely consists of short gingle notes and semiquaver beats. By contrast, the part in the B section contains longer held notes; possibly a series of extended bass notes or a round bass are implied in bars 61–68 (Ex. 10).

Ex. 10 Sustained notes in the tambourine part of Steibelt's arrangement of La Retour du Zephyr, fourth movement, bars 45–84 (London: Preston, 1804)

The Scottish character of the fifth movement, which is rhythmically and melodically constructed like a polka, also provided a suitable opportunity for Steibelt to include a tambourine part. Indeed, Scottish music was a popular form of domestic and salon musical entertainment, especially in Britain, and the inclusion of a tambourine part would allow the vital rhythmic effects to be greatly enhanced.Footnote 49 Here, the tambourine provides extra rhythmic support to the buoyant dotted melody, whilst passages such as bars 25–26 and 29–30, in which the tambourine player was expected to alternate between flamps and semi flamps, create a choreographic visual spectacle that greatly enhances the relationship between music, dance and the female performer (see Ex. 11).

Ex. 11 Tambourine part in Steibelt's arrangement of La Retour du Zephyr, fifth movement, bars 21–42. The alternating downwards and upwards stems, bars 25–26, 29–30, 33–34, and 37–38, imply a rapid change between flamps and semi flamps. These provide considerable contrast to the dotted, Scottish polka-style rhythms.

The tambourine part in the final movement functions in a similar way to that of the fourth movement, providing rhythmic doubling to the melodic line. The reasons for the instrument's inclusion here are clear. Both rhythmically and visually it contributes a suitably brisk finale to the ballet arrangement. The performer would doubtless have been expected to raise the tambourine above her head when playing at the final cadence in order to create the most spectacular ending possible. While its success in Paris is likely to have been the primary factor behind Steibelt's decision to arrange the ballet for domestic ensemble, its role in relation to the growing popularity of dance and music amongst girls in domestic settings and private salons is also significant. Rather than being used in a passive setting for the purposes of domestic pleasure, longer works that include a part for tambourine, such as Dale's Grand Sonata and Steibelt's adaptation of La Retour du Zephyr, contributed to a social climate allowing girls to play music in a more elaborate, dance-like fashion.

In the wider context of British society in the aftermath of the French Revolution these pieces with tambourine parts were the perfect fit for female performers, in that they provided a way of combining beauty and elegance with individualism and display, without ever becoming dominating. The fashion subtly reflects the forging of a new feminine identity, one that, as Elizabeth Morgan argues, relied ‘on [women's] powers of independent reason and individual will’.Footnote 50 In each work discussed in this article the tambourine predominantly takes an accompanying role: this is clear in the alternations between flamps and semi flamps, as seen, for example, in the short waltzes, as well as Steibelt's Turkish Rondo and much of the arrangement of La Retour du Zephyr; but the instrument is also displayed through the choreographic flourishes that make up much of the tambourine part in Dale's Grand Sonata. The combination of simplicity (in terms of structure, harmony and rhythmic patterns) and what might be called ‘subtle virtuosity’ (seen through the carefully choreographed turns or the dexterous beating patterns, jingles and bass notes) reflects, albeit modestly, the increasing opportunities for women to take part in domestic and salon music practices in ways contrary to social norms. The new-found freedom of expression reflected by these tambourine parts helped to create a more enabling environment for the activity of female musicians in private salons.

By the late 1810s, changes in fashion, dictated as much by the emergence or transformation of new genres as by technological developments, played their part in marginalising the tambourine as a salon instrument. Later editions of Steibelt's arrangement of La Retour du Zephyr, for instance, are scored only for solo pianoforte (and occasionally violin), with the tambourine part omitted, while around 1825, Robert Birchall issued a new arrangement of Steibelt's Turkish Rondo for piano and violin, without tambourine accompaniment.Footnote 51 New salon genres provided opportunities for female musicians to express themselves far more elaborately than any tambourine piece could. The transformation of the Lied as a suitable genre for women to perform and compose, together with innovative developments in piano construction, and the obvious limitations of the tambourine as an instrument, meant that by the 1810s there were far more impressive ways of showcasing female musicianship in the salon. Beautifully decorated patent tambourines, delicate gingle notes and elegant turns of the instrument and the body were trumped by emerging art forms that had the potential to revolutionise the role of female musicians in the salon.Footnote 52 Furthermore, the Janissary stop became especially popular on pianos during the Viennese Biedermeier (1815–1848), which perhaps rendered any additional tambourine accompaniments surplus to requirements on the Continent. In the light of these developments, the tambourine, as far as I am able to tell, played very little part in salon or domestic music from the late 1810s onwards.

The tambourine represented a bridging point between the strictly defined role of women's musical activity in the eighteenth century and the greater freedom of expression, both in terms of performance and composition, that was beginning to emerge in the early nineteenth-century salon. The variety of visually stimulating choreographic techniques I have explored here, many of which would have been incorporated into other works ad libitum, provided creative opportunities for women that stood outside the boundaries of typical practice in the early nineteenth century. In this respect, the tambourine precedes the role of the Lied which, as David Gramit observed, ‘provided a creative outlet for women, who were strongly discouraged from other public creativity, even while its position within the hierarchy of musical genres reinforced the ideologies that justified their exclusion’.Footnote 53 The brief fascination with the tambourine in domestic and salon music is very much of its time and place. While the combination of simplicity and subtle virtuosity still reflected the graceful, elegant attributes that girls were expected to display, it hinted at the growing sense of freedom and expression that would become key traits of nineteenth-century salon culture. Today, the limits of the performed repertory mean that the musical and historical significance of the tambourine's brief role in domestic and salon music is largely ignored. Although the fashion was short-lived, the role of the tambourine at the turn of the nineteenth century provides a small but significant example of the changing nature of female musicians’ activity in the salon, and of the relationship between music and movement, as well as the visual dimension in salon performance. These works evidently formed part of a musical landscape in the early nineteenth-century salon that is richer and more varied than scholars have hitherto suspected.