Oxford, Balliol College, 173A is a codex created sometime in the fifteenth century that combines two earlier codices: a collection of works of Aristotle copied in the late thirteenth century (fols. 1–73) and a collection of early music theory copied in the twelfth or thirteenth century (fols. 74–119; Table 1).Footnote 1 The first music fascicle (fols. 74–81) stands apart from the rest of the music portion in several ways: it has different handwriting from the rest of the codex; the gathering ends with a blank verso folio which could have served as the back cover of a small booklet; and the gathering features elaborate illustrations found nowhere else in the collection. Taken together, the evidence suggests that this gathering represents a self-standing booklet that circulated independently before first being bound together with the other music items, and then later with the works of Aristotle.

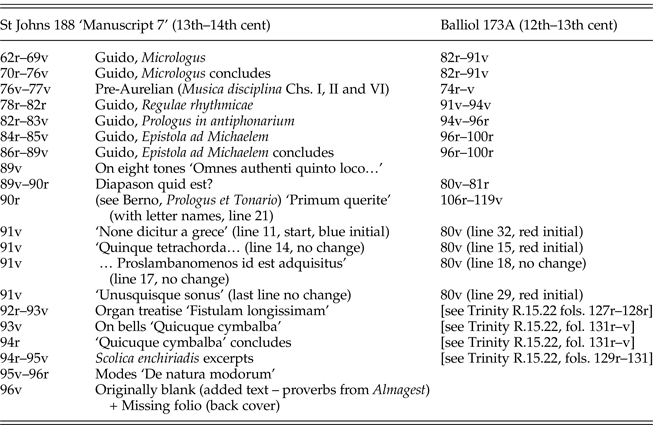

Table 1. Contents of Balliol 173A

Following a consideration of music theory fragments, compendia and booklets, this article proposes that fols. 74–81 of Balliol 173A is the work of a copyist learning the rudiments of music theory terminology. Such a booklet would have been useful for the copyist and/or other scribes both as an exemplar of their copying and as a reference for learning musical terms. This represents an audience for music writing often overlooked in the history of music theory – the scribes themselves. The users of this booklet may not have been interested in learning theory as a philosophical or learned subject, nor interested in performing or composing music. Rather, they needed to understand the music terminology they were learning to copy.

The contents of both the booklet on fols. 74–81 and the entire music portion are closely paralleled in one of the smaller manuscripts collected into Oxford, St John's 188 and also related to Cambridge, Trinity College R.15.22, which are summarised in a brief appendix at the end of the article. The three manuscripts demonstrate not only a body of similar texts, but also similar editing and arrangements of the texts.

Fragments, Tractatuli, Compendia and booklets

Fragments and Tractatuli

Many music theory codices contain short fragments of longer works – portions of treatises that exist in larger, complete forms in other sources. Other items commonly copied in these miscellaneous groups are short works, often referred to as tractatuli, that are complete in themselves and appear in the same length in other sources (i.e., they are not portions of larger works). Some of the topics of these short works are counterpoint, organology, monochord divisions and definitions of terms.Footnote 2 Diagrams and explanations of the Greater Perfect System are common self-standing items that appear in these collections well into the fifteenth century, even though by the eleventh century the range of notated music had exceeded that used by the Greeks.

The presence of a collection of fragments and tractatuli in a large codex usually marks a place in the copying process where a few folios are free after the major treatises have been completed – often, but not always, at the conclusion of a fascicle. An example of such a collection in the middle of a codex is Cambridge, Trinity College, O.9.29. Seven quires of eight bifolios were used to copy John of Tewkesbury's Quatuor principalia musice, ending on fol. 53r – the middle of the seventh quire. Although the codex continues to fol. 95 with works of Guido of Arezzo and Pseudo-Odo, those exemplars were either not ready to copy on to fol. 53v or the codex was assembled after the copying of the Quatuor principalia because the scribe used the remaining leaves in the quire (fols. 53v–56v) to copy several short works including the notes of the Greater Perfect System and a short counterpoint treatise. Guido's Micrologus begins at the start of a new quire (fol. 57r) and his works form the bulk of the codex to its conclusion without the addition of another tractatulus or fragment.

Compendia

Compendium is often used as a general term for any random collection of works that vary in size from a large codex to a small booklet.Footnote 3 Short compendia are often collections meant to fit a brief amount of blank space available in the copying process at the end of a quire. In a few cases, however, these compendia are transmitted between sources in the same in the same manner as a treatise by a single author. The Lexicon musicum Latinum medii aevi (LmL) of the Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften lists only eight items under the sigla ‘COMPIL’, for compilatio. These include items grouped as compilations in 1864 by Adrian de la Fage in Essais de dipthérographie musicale.Footnote 4 Christian Meyer titled one compendium as ‘Anonymous MK’ for its appearance in manuscripts now housed in Munich and Kassel.Footnote 5

Booklets

While most medieval writing and music has been preserved in large, bound codices, it does not necessarily mean that all medieval writing was created to be preserved in this format. The term ‘booklet’ indicates a small collection of leaves (sometimes only one quire) that was not originally bound into a collection with a sturdy cover, but circulated and used as a quick reference work. While not all booklets are compendia, a variety of short theory fragments collected into a booklet would be useful in teaching music, particularly for introductory students, and few music theory booklets have been studied as self-standing teaching materials.Footnote 6 Linda Page Cummins describes one such collection in Venice, Biblioteca del Museo Correr, MS 366, Part 4, fols. 425–56, a late fifteenth-century collection of theory she describes as ‘the interests of a musician who was also a teacher and who chose material that he considered practical, organised in a way he intended to be useful.’Footnote 7 The teacher's booklet was later bound into a composite volume of four manuscripts, totalling over 450 pages. Another example of a teaching booklet included in a larger collection was edited by Heinz Ristory as the anonymous Compendium breve de proportionibus, a short work on fifteenth-century mensural theory from Brussels, KBR, MS II 785, fols. 9v–11r, which Ristory states was created ‘for the further education of students’.Footnote 8

Many examples exist of writings about music, or musical works, which were created as small booklets and were either preserved in this format to modern times or can be clearly seen as having had circulated in an unbound form before later being collected into a bound book. Booklets for music notation have been studied by Charles Hamm on Du Fay (who used the phrase ‘fascicle manuscript’),Footnote 9 Andrew Tomasello on Ivrea, Biblioteca Capitolare, MS CXV (115),Footnote 10 Mark Everist on Paris, BnF lat. 11266,Footnote 11 and James Grier (and others) on the transmission of Aquitanian versaria through libelli or little books.Footnote 12

Outside of musicology, one of the leading scholars on booklets is Pamela Robinson, who studied early English manuscripts. In her seminal article, ‘The “Booklet”: A Self-Contained Unit in Composite Manuscripts’, she identified ten features used to identify a booklet. Of these features, Balliol 173A, fols. 74–81 stands apart from the rest of the codex in its different handwriting and illustrations, its different number of leaves to the quire, and how the final page is left blank (to serve as a back cover).Footnote 13 Expanding on Robinson's work, Ralph Hanna III, offered three more features to identify booklets. Balliol 173A, fols. 74–81 exhibit all of these: different quality of vellum, different sources and different subject matter from the rest of the codex.Footnote 14

The structure of the Balliol 173A booklet

The brief background on fragments, tractatuli, compendia and booklets provides a context for considering fols. 74–81 in Balliol 173A and why it might have been an independent booklet before being bound into a larger codex. Neither Roger Mynors's library catalogue of 1963 nor the Conservation Report done for a restoration of the MS in 2007 comment on the possible provenance of the codex.Footnote 15 The RISM description, proposed an English origin based on the notation used in the tonary (fol. 112v) and the note ‘ex dono William Gray’ in the volume and proposed that the section after the booklet (fols. 82–119) was copied from London, BL add. 4915, a source not used in fols. 74–81 (reinforcing Hanna's twelfth trait for identifying booklets). The present study follows RISM in assuming an English provenance from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries for the music gatherings of the codex. The construction of the booklet will be reviewed first (quality of vellum, fascicle structure, scribal hands and illustrations) followed by an analysis of the texts in the booklet and their arrangement.

Quality of vellum

The velum used in this quire is of consistently poor quality with several flaws throughout the grouping such as holes (fol. 74) and missing corners (fol. 79). These holes were in place when the copying began (the words wrap around these imperfections), indicating that the scribe was working with less-than-ideal materials. Holes appear in later quires of the music section as well (at fols. 83, 87 and 88). But, the number of holes in the velum decreases from the high number in the first music gathering to the end of the codex – the bifolios of this gathering are of the poorest quality in the codex, which would represent Hanna's eleventh characteristic of booklets: variation in the quality of vellum.

Fascicle structure

The quire containing fols. 74–81 has caused some confusion in previous descriptions of the codex including Roger MynorsFootnote 16 and the Conservation Report written for a restoration of MS 173A in 2007.Footnote 17 Both manuscript descriptions noted the missing folio after fol. 74, which breaks in the middle of a sentence making the missing leaf obvious (labelled ‘fol. β’ in Figure 1). The binding stitching clearly appears between fols. 76 and 77, indicating that this bifolio was originally the centre of the gathering. Given the value of vellum, blank folios in a manuscript are noteworthy and often indicate some type of interruption in the copying process, such as a break in time between copying sections or the use of different sources.Footnote 18 Rather than sewing in a single leaf (fol. 81) and leaving the verso blank, it is reasonable to propose that there was originally an entire bifolio consisting of the current fol. 81and a now wanting folio (labelled ‘fol. α’ in Figure 1) serving as a front cover. It may have served as the pastedown for the original music theory collection and was lost when that codex was disassembled to be bound with the Aristotle works in the late fifteenth century.

Figure 1. Proposed construction of booklet now Balliol 173A fols. 74–81.

The gatherings after fol. 81 comprise four quires of eight bifolios and a concluding gathering of six (as described in Table 1). These gatherings contain treatises of Guido and Pseudo-Odo along with a concluding tonary; they are copied without any blank folios or added short texts. The proposed fol. α and the description of the booklet quire as a grouping of ten bifolios would confirm Robinson's seventh trait of booklets (number of leaves to the quire differ from other parts of codex), and the blank on fol. 81v coincides with her ninth trait (last page left blank). The blank, fol. 81v, does not appear to be noticeably soiled or rubbed beyond the use seen in the other folios (Robinson's sixth trait), which would indicate that it did not circulate as an independent booklet very long before being combined with the other quires in the codex.

Scribal hands

In the music portion of the codex, the leaves are uniform in size (175mm × 95 mm as given in RISM) using a single writing block (37 lines per page) with the exception of the concluding tonary, which uses the same page size, but in a three-column format. RISM identifies three copyists for the music portion of Balliol 173A: Hand A for fols. 74–81, Hand B for the rest of the theory treatises (fols. 82–106) and Hand C for the tonary (106–119). Hand A is notable for the rounder shaping of the letters and the wider spacing between letters and words than in the rest of the music codex. In particular, the shape of the ‘a’ in Hand A often features a slight serif to the left whereas in Hand B the ‘a’ more often ascends without a flourish. Conversely, the ligature of ‘re’ in Hand A is smooth but Hand B adds a small flourish between the letters.Footnote 19

Another hand, not cited in the RISM description, appears for only twelve lines beginning at the bottom of fol. 75r and continuing only for the first third of fol. 75v, which might be referred to as the ‘Master Hand’ (Figure 2). With darker ink and more elaborate flourishes than Hands A, B, or C this scribe also copied the text for the Greater Perfect System (if not the artwork) and appears only in this gathering. Of particular note is the elaborate ligature to lengthen the word ‘doctoris’ in order to align the right-hand margin while leaving space for an illustration to be added later. While it is impossible to know exactly why a better scribe suddenly appears at this point in the manuscript, perhaps it is because this section of the MS requires the text scribe to leave spaces for images that a later artist will fill in. If Hand A was a student scribe who was not matching the source text line-for-line (because of the holes in the vellum, the comparative spaciousness of his writing style, or for other reasons), it may not have been immediately clear to him how to break his text to make room for the images – a problem in many treatises with examples and diagrams added later in the production process.Footnote 20 Perhaps his mentor showed Hand A the solution to this problem and asked him to continue on his own – a learning curve he sometimes failed to master as seen in the crowded spacing on fol. 76v. The Master Hand appears only in the gathering of fols. 74–81, which supports Robinson's second trait used to identify a booklet – different handwriting in the section.

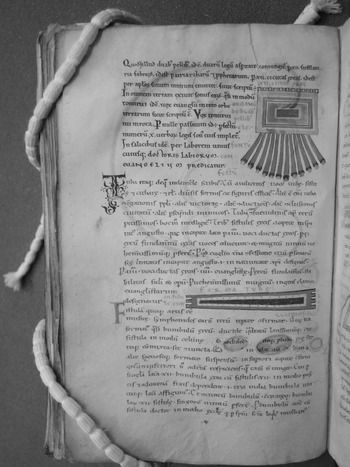

Figure 2. ‘Master Hand’ and illustrations, Balliol 173A, fol. 75v. Reproduced by kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Balliol College.

Illustrations

A unique characteristic of the gathering from fols. 74–81 is the inclusion of elaborate, colourful diagrams absent from the rest of the music section. This includes the representation of the Greater Perfect System on fol. 75r and the illustrations in the section on musical instruments from the Pseudo-Jerome epistle (also seen in Figure 2). While there are illustrations in later sections of the music codex, none are as elaborate or as colourful; the others use only black and red inks and do not include the blues and greens of the illustrations in the booklet. This agrees with Robinson's third trait. None of the illustrations following fol. 81 are as careful or skilfully done, which may indicate that the illustrator (as well as the scribe for this gathering) was learning the craft under a more accomplished master.

The content of the Balliol 173A booklet

If the preceding arguments are correct, then Hand A was given five bifolios (ten leaves) of less-than-ideal velum to copy a collection of music theory works. As a hypothesis, I propose Hand A was not the compiler who oversaw the layout of the gathering, but was following directions as part of a learning process (perhaps from the Master Hand). The work was created to be only a booklet of these bifolios so that fol. α was probably blank both recto and verso to serve as the front cover. Hand A then began on the current fol. 74r with four major writers to be included: materials collected by Aurelian of Réôme into the Musica disciplina, and works or selections of Pseudo-Jerome, Isidore of Seville and Cassiodorus. The texts in this section (Table 2a) include some of the earliest writers in Latin music theory discussing speculative topics. The sources are significantly different from the items in the rest of the music codex, which include Guido's Micrologus, Regulae rhythmicae, Prologus in antiphonarium, and Epistola ad Michaelem as well as the Pseudo-Odo Dialogus de musica and Berno's Prologus in tonarium, which are generally later and deal with practical aspects of music. These differences reflect Hanna's thirteenth traits of booklets.

Table 2. Sources for booklet

Following these writers, the scribe and compiler still had most of fols. 80v–81r to be filled with brief items such as a discussion of the tetrachords in the Greater Perfect System and a dialogue on intervals, leaving fol. 81v blank as a back cover. Of the small items, which form the concluding compendium (Table 2b), those that can be named are later than Cassiodorus and Isidore. This indicates a useful trait of compendia – they allow for the insertion of newer, more recent teaching than the major writers in the body of the collection.

Aurelian (Part I)

The Balliol theory booklet begins with an excerpt from Aurelian's Musica disciplina.Footnote 21 Aurelian's treatise exists in a number of versions which differ in content – specifically, and he appears to have synthesised material from a general work on music with a detailed description of the emerging eight-mode system (often referred to as De octo tonis). In her critical edition of the work, Anna Morelli posits that the text of Aurelian in both Balliol MS and St John's 188 (a source which will be discussed in the Appendix) both derive from an unknown source which omitted De octo tonis.Footnote 22

In organising the Balliol booklet, the compiler divided the abbreviated source material into two parts that serve as a frame for the booklet (labelled Aurelian Parts I and II in Table 3). The first set of excerpts in the Balliol booklet begins with what is now Chapter I and the beginning of Chapter II of Aurelian's complete work; they include a general introduction to music (stories of music's power from antiquity and the Bible) and are themselves drawn from earlier sources (including Cassiodorus and Isidore).Footnote 23 The excerpt from Chapter II ends at line 9, just before Aurelian notes that the diapason is found in the Antiphon Inclina Domine aurem tuam in the complete version of the Musica disciplina. Following the omission of the rest of Chapter II, Chapters III to V are also absent from the Balliol booklet.

Table 3. Borrowings in Balliol 173A booklet

We might assume that Hand A continued his excerpts from Aurelian Chapter VI and/or Chapter VII on the now wanting ‘fol. β’ both recto and verso. If so, the booklet may have contained a description of musical intervals and mathematical proportions (Chapter VI) and/or the Boethian distinction between a musician and a singer (Chapter VII).Footnote 24

Pseudo-Jerome and Isidore

Whatever appeared on the posited fol. β, the first set of excerpts from Aurelian stops by fol. 75r for an extensive diagram of the Greater Perfect System. The importance of the Greater Perfect System as a musical construct for the complier of the booklet is reinforced by the inclusion of a brief discussion of tetrachords in the concluding compendium (fol. 80r).

The booklet next presents two short music treatises. The Epistola ad Dardanum provides a speculative discussion of instruments from scripture and was traditionally assumed to be by St Jerome (d. 420), but currently is seen as an anonymous work of the ninth century.Footnote 25 The transmission of the work in its numerous sources is notable for its elaborate illustrations of allegorical instruments such as the organum, tuba, cithara, sambuca and timpanum. The relevance of the text and illustrations to actual instruments of the early Middle Ages, however, is negligible.Footnote 26

This is followed by the section on music from Isidore of Seville's Etymologiarum,Footnote 27 a source for some of the earlier passages from Aurelian's Musica disciplina. Isidore drew his ideas from Cassiodorus (who follows in the MS) and from Augustine of Hippo and presents general discussions of music as a liberal art.Footnote 28

Cassiodorus and Aurelian Part II

The compiler then included an extract from Cassiodorus and returned to the Musica disciplina to conclude the major treatises of the booklet. Cassiodorus's Institutiones was designed to train young monks in the basics of all the liberal arts, and his work presents more musical details than Isidore's, such as specifics on intervals and modes.Footnote 29 But the compiler included only the first half of the work and omitted the passages of Cassiodorus that are most basic to the understanding of musical structure. The section on intervals may have been covered on the now missing passages of Aurelian on fol. β or omitted due to the general avoidance of specific details of music structure in the Balliol booklet. Cassiodorous's listing of fifteen modesFootnote 30 was probably omitted as it conflicts with the excerpt from Aurelian Chapter XIII which gives eight modes.Footnote 31 Isidore, however, cites fifteen tones as well, but merely gives the highest and lowest (Hyperlidian and Hypodorian, fol. 77v) rather than detailing each mode by name. This would have created a contradiction for a careful reader between the older fifteen-mode system and the newer eight-mode system, but not as noticeable as giving a complete list of fifteen modes in one section and then a list of eight modes in other sections. Given that half of Cassiodorus's work is omitted and that much of what is present merely repeats material in either Isidore and Aurelian, the decision to include Cassiodorus at all may be due to the desire by the compiler to include the important traditional writers on music as a liberal art and not because of any new, additional information the source adds to the collection.

The compiler returns to the materials of the Musica disciplina to give a short excerpt from what is now Chapter VIII on the eight modes.Footnote 32 The compiler of the Balliol MS omits the more abstract and speculative ideas on the modes and their relationships to signs of the zodiac (VIII: 22–46). Morelli suggests that the next section of Aurelian's complete work, Chapters X–XIX (often referred to as De octo tonis), was most likely missing from the source used to copy Balliol 173A. The section gives detailed discussions of each mode and numerous examples from the chant repertoire, and also discusses how to adjust the psalm tone recitation termination to smoothly transition to the initial pitches of different antiphons in each mode.

The compiler concludes his excerpts from Aurelian (and the section of the major treatises) with what is now the beginning of Chapter XX (lines 1–24) – a general discussion of the types of chants in the Mass and office, but without citing the musical structure of specific chants. By dividing the materials from the Musica disciplina in half and putting the other major sources between the two sections, the complier was able to conclude the section of the major sources with a brief explicit from Aurelian's work that can also serve to summarise all the authorities included in the booklet.

Concluding compilation

Once the major treatises were finished, the compiler and copyist had fols. 80v–81r as blank leaves to fill with a compendium of small items.Footnote 33 Of these the most notable is the brief dialogue Diapason quid est? First edited by Karl-Werner Gümpel from a Spanish source; the work exists in about a dozen manuscripts from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries.Footnote 34 The dialogue is often included in codices which transmit theoretical works by Boethius and Guido that already have extensive discussions of intervals. The short tractatulus does not add anything to the discussion of intervals in these larger works, but it can serve as a handy reference item for those unfamiliar with musical terminology. The diapason, for example, is described in the usual terms of the similarity of low and high sounds. No proportions are given, but instead the definition concludes with a practical metaphor – the days of the week: ‘just as the first day and the eighth are similar, so too with the octave’ (‘sicut in diebus primus et octavus similiter ita in diapason’), a metaphor also used by Guido of Arezzo.Footnote 35

Ordinatio and compilatio

Viewing the contents of Balliol 173A fols. 74r–81v as a whole, the reordering and editing of the sources reflect the concepts of ordinatio (ordering of materials in a book) and compilatio (the editing of materials from various sources) described by the English palaeographer and Chaucer scholar Malcolm Beckwith Parkes:

The compiler adds no matter of his own by way of exposition (unlike the commentator) but compared with the scribe he is free to rearrange (mutando). What he imposed was a new ordinatio on materials he extracted from others. … The compilatio derives its usefulness from the ordo in which the auctoritates were arranged.Footnote 36

In this reading of the booklet, the compiler edited the material Aurelian later used as the basis of the Musica disciplina into a frame into which other materials would be joined to create a new ordering (ordinatio) for a booklet that would amplify and coordinate with it.

Having covered the basics of music as a liberal art from his major sources as he edited them, the compiler then added materials to create a fuller understanding. He addressed the issue of the Greater Perfect System with both an extensive diagram (fol. 75r) and a brief prose description (fol. 80r). Simple, easy to understand definitions of intervals were added by the dialogue Diapason quid est? and the names of the eight-mode system using Dorian and Hypodorian (rather than Protus authenticus and plagus) were added as the last item on fol. 80r.

Nevertheless, there are a small number of topics repeated in the booklet, which, given the amount of editing undertaken, may represent those ideas the compiler felt needed to be stressed or were unavoidable given his sources (Table 4). The scribe copied the myth of Pythagoras and the idea that the word ‘music’ is from the muses three times in the booklet. In addition, the complier may have included the excerpt from Cassiodorus only to assure complete coverage of the major writers on music as a liberal art, as it added no new information to the collection and, instead, creates a contradiction on the number of modes (fifteen or eight). The concluding compendium (fols. 80v–81r) served many practical functions: 1) it provided a place for excerpts for more recent writers to be added to the collection; 2) it provided information omitted from the body of the collection; and 3) it could have served as a quick reference for basic information.

Table 4. Parallels within the booklet

The possible uses and history of the booklet

While the booklet could have served simply as an introduction to music as part of the study of the liberal arts in general, the presence of an overseeing editor (best seen in the beautiful penmanship on fol. 75v), presents the possibility that the work could have served as an exemplar for copyists on how to copy text with blank spaces for illustrations and examples. If so, an admittedly speculative narrative for the Balliol 173A booklet may be as follows: a scribe needing to learn the basics of music was given five bifolios of relatively poor quality on which to copy a selection of texts covering musical terms arranged into a compilatio by the compiler of the work who knew the source treatises well and could edit the texts in a coherent way. Part of such an assignment was learning how to leave blank spaces for the illustrations or musical examples. After completing the booklet with several major items copied in order (Aurelian-Part I, Pseudo-Jerome, Isidore, Cassiodorus and Aurelian-Part II), the final leaves of the booklet (fol. 80r–81r) were used to add a number of small items that explained basic terms and concepts, providing a handy appendix.

Sometime later, the decision was made to create a music theory codex including the works of Guido and a tonary – works which demanded that the reader know how to read music in notation and have an understanding of chant. While the contents of the booklet do not exactly align with the Guidonian works, the booklet made a useful first section for the new music codex.Footnote 37 The blank first folio of the booklet (fol. α) was available as a paste down to bind the front of the music codex and the back cover of the booklet (fol. 81v) was left blank. When the music codex and the Aristotelian texts were combined in the fifteenth century to create the current version of Balliol 173A,Footnote 38 the pastedown fol. α was lost; fol. β was lost at some point its history before the numbering of the entire codex.

Appendix

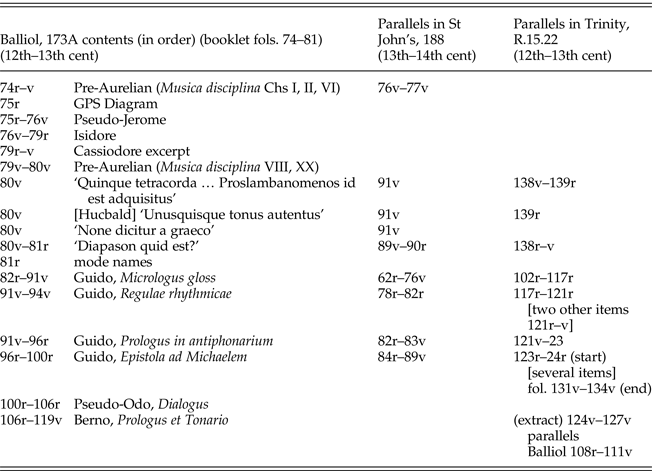

The music portions of Balliol 173A are related to at least two other medieval English manuscripts: Oxford, St John's College, 188 and Cambridge, Trinity College, R.15.22.Footnote 39 The parallel texts in these sources (and a few others) were noted in RISM and include the works of Guido (which have numerous sources in the period) but also sections of the smaller works, specifically portions of the Aurelian sources and/or the same material used for the concluding compendium, often in similar order.

St John's College 188

St John's 188 is composite codex from the late thirteenth century comprising ten separate manuscripts as described in Ralph Hanna's catalogue of the library.Footnote 40 Like Balliol 173A, the current version of St John's 188 combines scientific works (such Johannes Scaroboso's Algorisums sive tractatus de arte numerandi and a treatise on the astrolabe) with music theory works.Footnote 41 Hanna's Manuscript 7, which contains only music theory works in a single hand, reorders much of the materials found in Balliol 173A and also has several concordances with Cambridge, Trinity R.15.22 (discussed in the following subsection).

St John's 188, Manuscript 7 contains four quires of four bifolios and a concluding quire, which originally had two bifolios (the last page is now missing; Table 5). It begins with a gloss of Guido's Micrologus,Footnote 42 a version of which was also the first item after the Balliol theory compendium. This comprises most of the first two gatherings but left three blank leaves (fols. 76v beginning on line 4 to fol. 77v). Rather than continue with the copying of the Guidonian texts as in Balliol 173A, for some reason the scribe finished these blank leaves with a small work that fit the space – the first group of early chapters of Aurelian found in Balliol 173A, fol. 74r–v.

Table 5. Contents of St John's 188 compared with Balliol 173A

The scribe began the third gathering with Guido's Regulae rhythmicae, followed by the Prologus in antiphonarium, and Epistola ad Michaelem, which are present in the same order as Balliol 173A (and in many other manuscripts). The Guidonian works occupy fols. 78r–89v in the St John's manuscript, taking up the entire third quire and concluding in the middle of the fourth. This left the scribe almost four complete blank leaves (fol. 89v starting at line 4 to fol. 93v), which were then filled with several small works but continued past these leaves and required the addition of a fifth quire of only two bifolios to complete the codex. The gathering probably ended with a blank folio (both recto and verso), which has since been lost so the gathering ends with fol. 96r. Some (but not all) of these items parallel the brief works at the conclusion of the Balliol booklet, including the Diapason quid est? dialogue. The smallest fragments appear in close proximity in both sources: a brief treatment of the noeane syllables from Frutolfus's, Breviarium (Chapter XIV:III), a review of the tetrachords and pitch names in the Greater Perfect System (from an unknown source), and a brief treatment of mode from Hucbald, De harmonica institutione (as detailed in Table 5). The concluding compendium in St John's 188 includes several items not present in Balliol 173A such as fragments on instruments (organs and bells), which are, however, present in Cambridge, Trinity College, R.15.22 (discussed in the following subsection).

St John's 188 is the only know source that transmits the same fragment of the Aurelian's chapters as they appear in the Balliol 173A booklet, making these two sources closely related, as was observed by Morelli. But rather than breaking the source into a compilatio structure, the scribe of St John's 188 used only the early chapters from Aurelian as a short tractatulus to fill out the empty folios of a gathering, indicating the following treatises by Guido were not yet ready for the copyist to use. The Diapason quid est? dialogue and other brief materials are in similar positions of a concluding compendium in St John's 188, the same role those works have in the Balliol 173A booklet – further evidence for the close relationship between these two sources. The scribe/compiler of St John's 188 did not include any of the other works by the older writers in the Balliol booklet – Pseudo-Jerome, Cassiodorus, or Isidore.

Trinity College R.15.22

Some of the parallels in texts between Balliol 173A and St John's 188 also appear in Cambridge Trinity R.15.22 (as was noted in RISM), but it omits any passages from the early Aurelian chapters. Trinity College R.15.22 is a large codex, copied in the twelfth–thirteenth century by a single, elegant hand.Footnote 43 Following an opening of two bifolios as a guard, the Boethius De institutione musica takes up two-thirds of the codex. It is written on nine quires of four bifolios (fols. 5–76), one quire of five (fols. numbered 77–88, with three unnumbered leaves), and three quires of four bifolios (fols. 84–107). The Boethius ends on the bottom of fol. 101v near the beginning of the thirteenth quire (fols. 100–107).

The scribe continues with a glossed version of Guido's Micrologus, which takes up the remainder of the thirteenth quire, all of the fourteenth (fols. 108–115) and ends early in the fifteenth gathering. There then appears three short works of Guido included in Balliol 173A, St John's 188, and many other sources, starting with the Regulae rhythmicae, which is given as the Brevis sermo in musicam but without a direct attribution to Guido (fol. 117r). But rather than continuing with the next two Guidonian texts as they frequently appear (the Prologus in antiphonarium and the Epistola ad Michaelem), the Trinity scribe inserts a pair of small items on the tones and verses on the muses.

Following the verses on the muses, the MS continues with Prologus in antiphonarium with a clear attribution to Guido on fol. 121v and begins the Epistola ad Michaelem but without a rubric citing the author with the text, Ad inveniendo ignoto cantu.Footnote 44 The Epistola continues to the start of the sixteenth gathering on fol. 124r, line 21, with the musical examples beginning Alma rector mores nobis. At this point, Guido is about to discuss the range of pitches and the division the monochord. The scribe, however, does not continue with Guido's treatise but enters several non-Guidonian items that will complete the sixteenth quire, all of the seventeenth and end at the start of the eighteenth gathering, which is also the final quire. These tractatuli are given clear rubrics and/or large drop-capitals of several lines in the margins (Table 6). They all expand upon the range of notes which is the topic that Guido's treatise returns to on fol. 131v, line 23 with a rubric guiding the reader back to Guido with a discussion of the names of seven pitches (relating the seven pitches to the days of the week) followed by a division of the monochord. Many, but not all, of the inserted items have parallels in Balliol 173A and/or St John's 188 (Table 7).

Table 6. Tractauli in Trinity College, R.15.22 (fols. 124–131v) inserted into Guido's Epistola ad Michaelem

Table 7. Comparison of Balliol 173A with St John's 188 and Trinity R.15.22

The insertions into the Epistola ad Michaelem function as a compilatio. To return to the ideas of Malcolm Parkes: the compiler did not add his own new material (unlike the commentator) but rearranged materials and imposed a new ordinatio on materials he extracted from others. This parallels the appearance of the Church Fathers within the frame of the Aurelian materials in Balliol 173A. As the compilatio in Trinity R.15.22 begins and ends in the middle of quires, however, it does not appear to indicate that the purpose of this compilatio was to create a booklet, as was the case in Balliol 173A. Trinity R.15.22 then concludes with several brief works, including the Diapason quid est? dialogue and a discussion of the Greater Perfect System beginning ‘Quinque tetracorda’. Taken together, the three codices do not merely transmit many of the same texts, but do so in similar ways within the fascicle structure of each codex, use similar methods of compilatio, and share several similar tractatuli in their concluding compendia.