1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 caused an immense health and economic crisis, but also posed an unprecedented challenge to democratic systems. During its early stages, the pandemic required strong government interventions to minimize the spread of the virus. Following technical advice from public health scientists, many governments implemented very strict lockdown policies and other mobility restrictions, ranging from school closures to working-from-home mandates. In later stages, governments introduced a wider variety of policies, involving new legislation, sanctions, and compensation packages.

Both the scale and nature of the threat, and the type of policy response were, for most citizens, unprecedented. Liberal democratic governments dictated exceptionally stringent rules, seriously restricting basic freedoms, in order to protect their citizens’ health based on expert advice. A number of recent studies have documented how the pandemic, along with its policy responses, led to some significant changes in citizens’ democratic preferences (Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó-Gimeno and Muñoz2020; Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, Ratzan, Palayew, Billari, Binagwaho, Kimball, Larson, Melegaro, Rabin and White2020; Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández-vázquez2021; Nielsen and Lindvall, Reference Nielsen and Lindvall2021; Becher et al., Reference Becher, Longuet-Marx, Pons, Brouard, Foucault, Galasso, Kerrouche, León Alfonso and Stegmueller2024).

A crucial yet unresolved question is whether the effects of the pandemic were temporary and faded away after it came under control, or whether the experience left long-lasting effects on citizens’ democratic preferences. A growing line of research has identified long-term socio-economic effects of previous pandemics such as the Black Death (Richardson and McBride, Reference Richardson and McBride2009; Voigtländer and Voth, Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012; Alfani and Percoco, Reference Alfani and Percoco2019) and the Spanish Flu (Aassve et al., Reference Aassve, Alfani, Gandolfi and Moglie2021). In this context, it is important to analyze, in real time, whether the attitudinal changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic were simply short-term preference changes as reactions to changing circumstances or, on the contrary, expressed deeper and more durable changes in preferences resulting from the formation of new beliefs about the world. In this second case, we could witness, over the long term, the formation of legacies of COVID-19 on the affected societies and their political systems.

The main goal of this paper is precisely to assess to what extent various components of the shift in citizens’ democratic preferences caused by the pandemic shock persisted after the end of the pandemic emergency. We focus on preferences for technocratic governance, on support for the centralization of power around a strong leader, and on willingness to restrict individual liberties.

The paper makes use of individual-level panel data and survey experiments collected over four years to monitor the evolution of several democratic attitudes throughout the entire crisis. We followed a representative sample of Spanish citizens from January 2020 to January 2024, fielding eight survey waves. Spain is a consolidated democracy that was heavily affected by the pandemic, both in terms of excess mortality and economic impact, experiencing a sizable contraction of 11% of its GDP in 2020.

Our design is especially suitable for understanding changes in democratic attitudes during and after the pandemic, and their patterns of persistence. The panel structure of the data allows us to study changes within individuals over time. Crucially, we measured technocratic preferences just before the outbreak, in January 2020, and were able to recontact the same respondents from the early stages of the lockdowns. We combine the longitudinal design with embedded survey experiments repeated over time, which we use to compare preferences for dealing with the pandemic relative to other global threats such as climate change or international terrorism.

Our findings, based on individual fixed effects models, provide evidence of a sizable and significant increase in technocratic preferences from the onset of the pandemic crisis in March 2020. Crucially, the shift toward technocratic preferences becomes persistent and remains significant over time, at least until January 2024.

On the other hand, using repeated survey experiments over time, we observe an initial strong effect of COVID-19 on citizens’ willingness to forgo rights and freedoms, and support for strong leadership as tools to fight the pandemic. However, these results display a pattern of gradual reversal, suggesting that the pandemic has not durably changed citizens’ minds regarding the value of liberties and power-sharing. Instead, individuals adjusted their willingness to accept these measures in response to the changing circumstances.

2. Pandemics and democratic preferences

The highly contagious and deadly nature of COVID-19 posed a massive collective action problem that was partially solved with emergency measures that fell well beyond what democracies usually do. Democratic leaders and citizens alike faced, in the context of the spread of the virus, a set of democratic dilemmas that had to be confronted in very little time. We can identify at least three main dilemmas that lie at the core of functioning liberal democracies.

The first one refers to the curtailment of civil liberties to stop the spread of the disease. Lockdowns, enforced social distance, or limitations on freedom of movement and protest were frequent across the democratic world. The second dilemma refers to the form of governance. As a reaction to the challenging circumstances, it was also common to observe the temporary concentration of power in the hands of the central executive, necessarily limiting the standard power-sharing and accountability mechanisms. Third, we also witnessed the increased role of technical expertise in the decision-making process, often at the expense of democratic deliberation and other procedural or political considerations.

A growing literature has shown how this process had important political effects on political trust (Nielsen and Lindvall, Reference Nielsen and Lindvall2021; Eichengreen et al., Reference Eichengreen, Saka and Aksoy2023), accountability (Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Sieberer, Tuttnauer and Andeweg2021; Becher et al., Reference Becher, Longuet-Marx, Pons, Brouard, Foucault, Galasso, Kerrouche, León Alfonso and Stegmueller2024), technocratic preferences (Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández-vázquez2021), satisfaction with democracy (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021), or the willingness to sacrifice rights and freedoms and unite around strong leaders (Alsan et al., Reference Alsan, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, Kim, Stantcheva and Yang2023).

As valuable as they are, most of these studies rely on cross-sectional evidence that does not provide information on the dynamics of preference change caused by the pandemic and their eventual persistence. There are some works that rely on (often short) panel data to study the effect of COVID-19 on political discontent and system support (Reeskens et al., Reference Reeskens, Muis, Sieben, Vandecasteele, Luijkx and Halman2021; Jø rgensen et al., Reference Jorgensen, Bor, Rasmussen, Lindholt and Petersen2022; Bor, Reference Bor, Jorgensen and Petersen2023), welfare and redistribution preferences (Ares et al., Reference Ares, Bürgisser and Häusermann2021; Enggist et al., Reference Enggist, Häusermann and Pinggera2022). But more research in the long run is important for our comprehension of democratic accountability and its future evolution. Short-run preference changes may have effects on the selection of politicians and the delegation of policy-making to experts. But in the long run, increased support for technocrats or strong leaders, and tolerance for civil rights restrictions may reshape the way democracies work.

Given what we know today about previous crises, it would not be exceptional to find long-term legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic. The democratization literature has shown that negative economic shocks can open the door to democratization in authoritarian regimes (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2001). Previous work has documented long-lasting effects of past pandemics and natural disasters on outcomes such as social trust, inter-group relations, or economic and political development (Richardson and McBride, Reference Richardson and McBride2009; Voigtländer and Voth, Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012; Alfani and Percoco, Reference Alfani and Percoco2019; Margalit, Reference Margalit2019; Aassve et al., Reference Aassve, Alfani, Gandolfi and Moglie2021).

There are several mechanisms through which the pandemic could have long-term political consequences. Preference changes may generate a shift toward a new, self-reinforcing political equilibrium. For example, in the case of technocratic preferences, the literature has argued that natural disasters can change voters’ behavior by changing their priors about politicians’ relevant qualities (Healy and Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Bueno de Mesquita and Friedenberg2018), focusing on technical expertise at the expense of other characteristics such as substantive or descriptive representation. Moreover, technocratic preferences are likely to be absorbed by the dynamics of party competition and political selection (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017; Sánchez-Cuenca, Reference Sánchez-Cuenca(2020); Bickerton and Accetti, Reference Bickerton and Accetti2021; Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022). Political parties are likely to strategically tailor their positions on the technocratic dimension in response to citizens’ demands, with voters later following such party cues. This process might lead to an endogenous, self-reinforcing technocratic shift.

The same might be true for support for restricted individual liberties. Leaders with a project of democratic erosion may be able to take advantage of citizens’ willingness to accept strong leadership and limitations on individual rights and freedoms in exchange for protection against the virus. However, this may be temporary, as voters are likely to prefer strong, centralized leadership in times of crisis (Alexiadou and Gunaydin, Reference Alexiadou and Gunaydin2019), not because crises change their worldviews, but because they may make certain forms of governance more convenient while they last. Vasilopoulos et al. Reference Vasilopoulos, McAvay, Brouard and Foucault(2023) use panel data to show that emotions, and especially fear, were a crucial factor in acceptance of civil liberty restrictions. Some scholars have referred to Terror Management Theory and mortality salience to explain some attitudinal changes during the pandemic, as citizens cling to their worldviews as a distal defense mechanism (Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Lockett, Greenberg and Solomon2021). Although we do not directly address these psychological underpinnings, the observable implication is that as hospitalizations and deaths due to the pandemic declined (and with them, perceptions of individual vulnerability), the willingness to accept exceptional measures should decline as well. If this is the case, democracies may prove resilient to the emergency restrictions of rights despite the incentives for would-be authoritarians to use the crises as opportunities for backsliding.

3. Data and empirical strategy

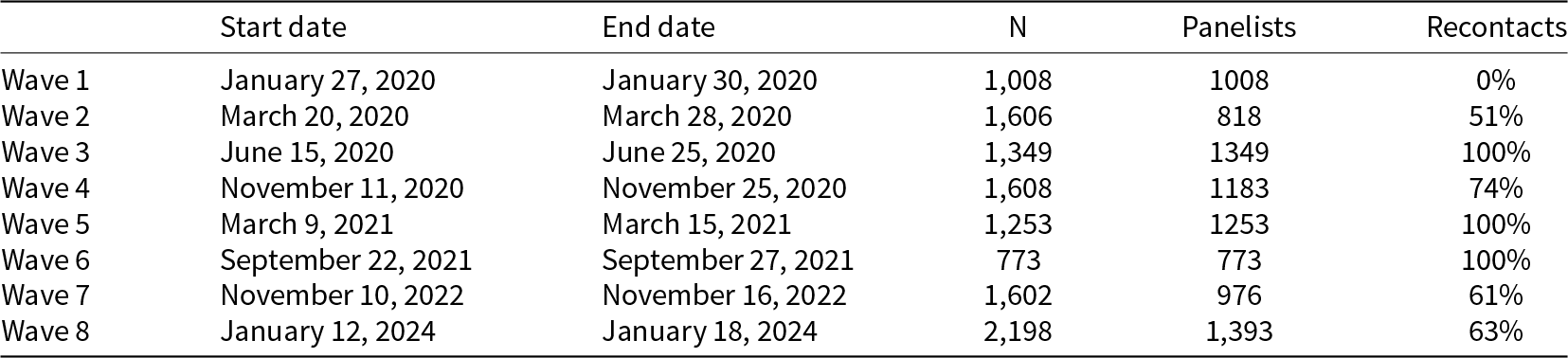

We fielded eight cumulative online surveys in Spain between January 2020 and January 2024 with the company Netquest Spain. Table 1 shows the fieldwork dates, sample sizes, and the number of panelists.Footnote 1 In each online survey we used age, gender, region, and education quotas to better represent the actual voting-age Spanish population. To limit self-selection, survey respondents cannot self-register for the panel, and membership is strictly based on individual invitation. Respondents are paid a fixed compensation for answering each survey.Footnote 2

Table 1. Fieldwork dates and size of survey waves

The first online survey took place in January 2020, before the outbreak of the pandemic crisis in Europe. The second one was fielded in March 2020, very shortly after the Spanish PM’s declaration of a state of alarm and a mandatory lockdown with a restrictive stay-at-home order across the country. The third wave was implemented in June 2020, when the strict lockdown had been relaxed but many mobility and work restrictions were still in place. We then fielded the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh waves between November 2020 and November 2022, at different stages of the evolution of the pandemic, with restrictive measures gradually declining. Finally, the last wave was fielded in January 2024, months after the end of the global health emergency had been declared, when all measures had been lifted and the pandemic had disappeared from Spaniards’ everyday lives.Footnote 3 Appendix H reports cross-country comparisons of health and economic effects of the pandemic, as well as the stringency of government policies, suggesting that Spain was mostly quite similar to Canada, France, Germany, the UK, or the US.

The panel structure of the cumulative survey data allows us to estimate individual fixed effects models and to identify individual changes in democratic attitudes over time. We use this strategy to assess the impact of the pandemic on technocratic preferences. Additionally, we embedded several randomized experiments in the online surveys from wave 2 onward. These experiments were designed to estimate the effects of COVID-19 on democratic attitudes, in comparison to other threats with distinct political implications, such as climate change and international terrorism. We repeated the experiments over waves 2 to 8, so we can explore variation in democratic attitudes between citizens across time. The repeated survey experiments also allow us to explore variations in democratic attitudes between citizens across time.

Given the nature of the analyses, based on within-subject comparisons and on comparisons between groups, we do not weight the data. We use OLS individual fixed effects regressions of the form ![]() $Y_{it}=\delta_{t}+\gamma_{i}+\epsilon_{it}$, where δt and γi are wave and individual fixed effects, respectively, and individual fixed effects are normalized to sum up to zero. We cluster the standard errors at the individual level.

$Y_{it}=\delta_{t}+\gamma_{i}+\epsilon_{it}$, where δt and γi are wave and individual fixed effects, respectively, and individual fixed effects are normalized to sum up to zero. We cluster the standard errors at the individual level.

4. Results

4.1. Technocratic attitudes

We analyze the evolution of technocratic preferences over time, measuring them before, during, and after the pandemic outbreak. We use a set of four different survey questions to measure attitudes toward the role of expertise relative to ideology in government. First, we ask voters (on a scale of 1-7) if they would rather vote for a party that shares their ideas, even if they have not managed public affairs well or, alternatively, if they would prefer to vote for a party that has managed public affairs well, even if they do not share its ideas. Second, we ask whether respondents believe that politicians should put aside their political programs and approach public problems from a technical point of view. Third, we elicit our respondents’ level of agreement with the idea that “It is better to have experts, and not politicians, decide which policies are best for the country.” These survey questions tap into different dimensions of technocratic preferences and strongly correlate with Bertsou and Caramani Reference Bertsou and Caramani(2022) measures of technocratic attitudes.Footnote 4 Finally, we ask them to rate a set of qualities that politicians should have, in order of importance: honesty, ideological proximity, and competence.

Figure 1 displays the evolution of the marginal means per survey wave on our first three measures of technocratic preferences Results show that technocratic preferences immediately jumped following the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020. This change is strongly statistically significant and sizable: it increases by 10%, or 0.25 standard deviations. Interestingly, the preference for technocratic governance remains rather stable afterward. As of January 2024, the preference for technocratic governance was still significantly higher than in January 2020 (see Table F1 in the SI for the formal tests). In the Supporting Information, we explore these dynamics of persistence more in-depth: for many, the pandemic led to an immediate increase in technocratic preferences that have largely persisted over time. Moreover, in the Supporting Information (Figure D1) we show that persistence is driven by those same respondents who exhibited a positive shift in favor of technocratic attitudes by March 2020 and had below-average pro-technocratic attitudes before the pandemic. We also compare the persistence across participants depending on their initial wave (1st vs. the rest) and attrition (Figure C1). Overall, the results show that our findings are not driven by differences in the samples of the different waves nor by the fact that respondents answered the same questions several times.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Effect of the outbreak of COVID-19 on technocratic attitudes (individual fixed effects).

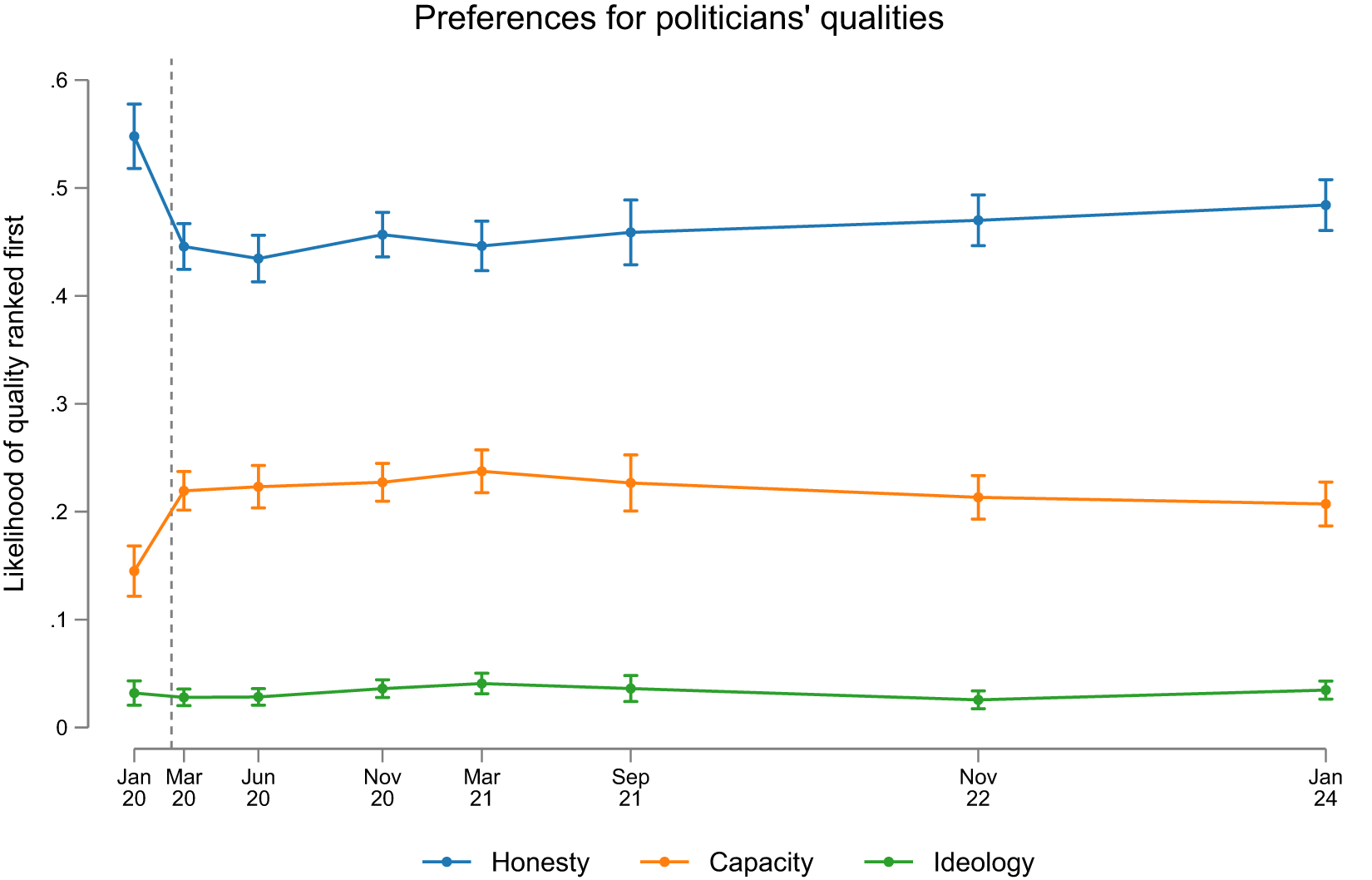

Figure 2 displays the coefficients of analogous specifications, where the outcomes are the respondents’ ranking of preferred qualities of politicians. Results show a significant increase in the preference for competent politicians following the COVID-19 outbreak. This preference increases by around 50% or 7pp, persists up to January 2024, and comes at the expense of preferences for honest politicians, which decline by around 20%, or 10pp. On the other hand, the preference for ideological congruence as the most important characteristic of a politician remains stable and very low. These patterns are very much in line with the observed increase in preferences for technocratic governance.

Figure 2. Effect of the outbreak of COVID-19 on preferred qualities of politicians (individual fixed effects).

4.2. Strong leadership and civil liberties

A large number of governments responded to the COVID-19 crisis with emergency powers that curtailed civil liberties, instead of relying on regular powers and citizens’ cooperation. In this section, we explore the dynamics of citizens’ assessment of this health vs. individual freedom dilemma.

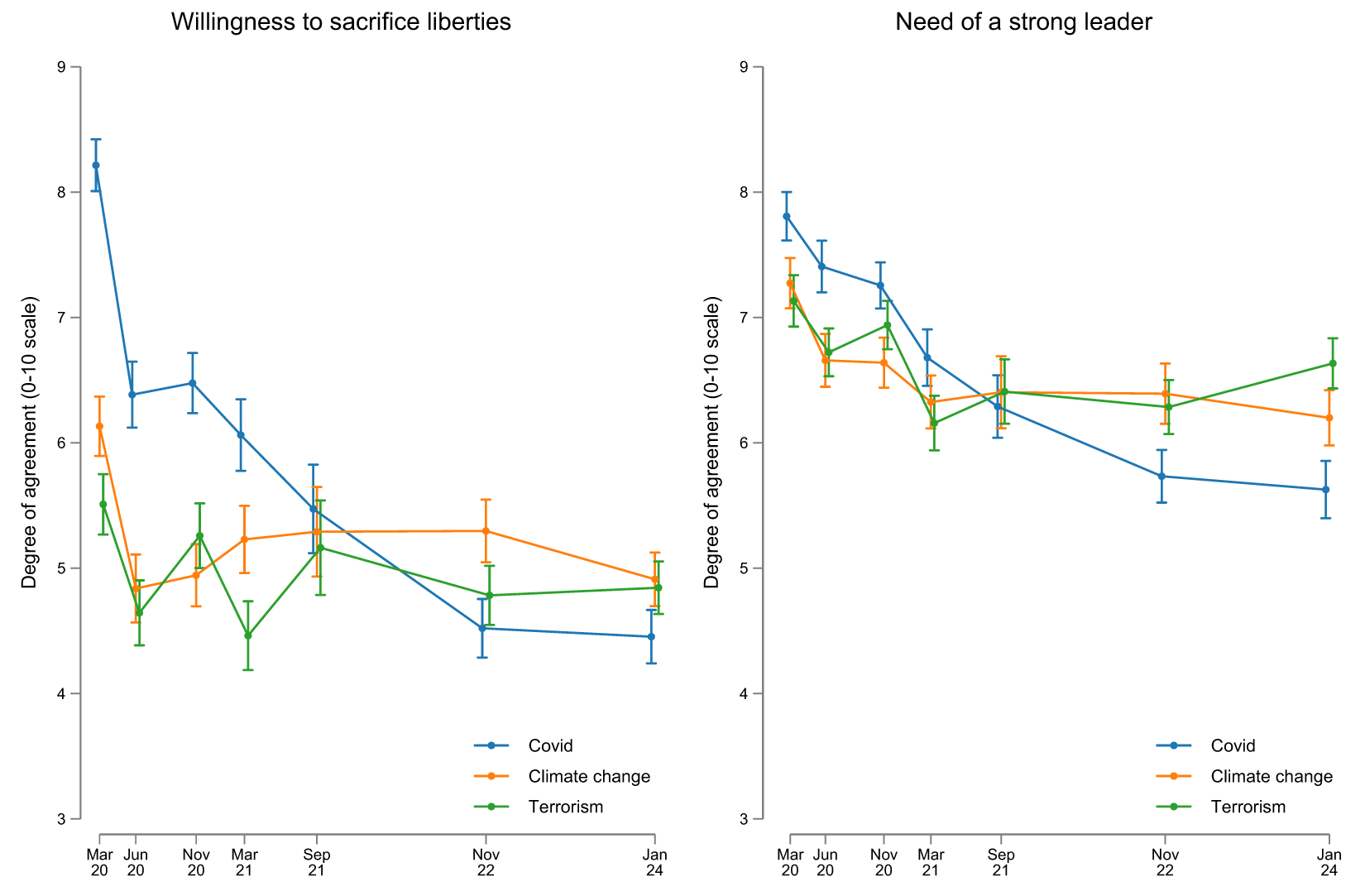

To this aim, we use the experiment that compared the three global threats: COVID, climate change, and international terrorism, with two additional outcomes. Specifically, we asked for the level of agreement with the following statements: (1) drastic measures should be taken to stop [coronavirus/climate change/international terrorism], even if that may entail a limitation of individual liberty and (2) in order to cope with a challenge like [coronavirus/climate change/international terrorism], we need to unite around a strong leadership. The nature of the threat was assigned randomly to each respondent.

We chose to focus on these three global threats in order to have a relevant benchmark to compare the COVID-19 shock. The three threats are similar in that they represent arguably exogenous shocks to democratic political systems with potentially severe consequences. The three also require coordination within and across countries that could be facilitated by strong leadership, and many effective steps to combat the COVID-19 spread, climate change, or terrorist strikes could entail important liberty reductions.

As shown in Figure 3, the COVID-19 crisis triggered a significantly different response than the other two threats in the first stages of the pandemic, especially during the peak of the first wave. Citizens were especially willing to support drastic measures even if they curtailed basic individual liberties. In March 2020, the average level of agreement with this trade-off was extremely high in the case of COVID, more than two points higher than in the cases of climate change and terrorism. Interestingly, at that moment, the willingness to limit individual freedom in exchange for protection was also comparatively high for the other threats considered, which suggests contamination across threats. After the first lockdown ended, however, support for this trade-off went down rapidly for climate change and terrorism, and was also moderated for COVID. Nevertheless, COVID-19 remained a significantly stronger argument for the trade-off until the last part of 2021. Already in 2024, COVID-19 is less and not more conducive to the willingness to sacrifice civil liberties.

Figure 3. Effect of different threats on willingness to sacrifice liberties and need of a strong leader (experimental evidence).

A similar, but less pronounced effect is found for the strong leadership outcome. All three threats lead respondents to support unity around a strong leader in the first months of the pandemic, with COVID-19 having the strongest effect in the first three waves. However, since early 2021 we have observed convergence and, by January 2024, the COVID-19 threat leads to less, and not more support for strong leadership.

We have shown that the outbreak of the pandemic caused a large initial change in technocratic preferences in terms of representation (preference for technocrats over politicians in government), management (preference for technical, not political, administration of public issues), and voting decisions (performance-based voting rather than ideological). Moreover, this initial shift seems to have largely persisted over time, even when the pandemic is no longer a relevant issue in the public debate. Willingness to accept limitations on freedom or claims of strong leaders, instead, has clearly faded as COVID-19 has ceased to be perceived as a real threat.

In the Supporting Information (Appendix E), we show that change and persistence in technocratic preferences due to the impact of the pandemic is heterogeneous across social groups. The initial change was more pronounced for women, young people, and the more educated, leading to greater convergence in preferences across groups that has largely persisted over time. On the contrary, we find a lower degree of convergence if we define groups along political lines. Also, our findings indicate that demand for technocratic rule increased more among those who subjectively perceived themselves as being more negatively affected by the pandemic. Finally, we find very little heterogeneity across groups in the impact of the pandemic threat relative to climate change or terrorism on demand for strong leaders or support for drastic measures that curtail basic civil liberties.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis shifted citizens’ democratic attitudes, and in some cases, the effects proved persistent. In this paper, we have analyzed how Spanish voters changed their democratic preferences throughout the pandemic. We tracked a representative sample of Spanish voters during the 2020-2024 period. By recontacting survey respondents, we built a unique individual panel survey that included some randomized survey experiments. Since the economic and health effects of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain were similar to those in other liberal democracies, there are no strong reasons to expect our results to be specific to the Spanish case.

We have identified relevant shifts in democratic preferences throughout the pandemic that are very much in line with recent literature. Most importantly, we document a high degree of persistence in the initial change in technocratic preferences. This suggests that the pandemic changed voters’ beliefs about the value of technical expertise: voters learned that expertise is more valuable than they initially thought. This technocratic shift does not imply that voters have become less supportive of democratic principles, but rather that they have developed a stronger preference for expertise. Remarkably, this switch became permanent even after the pandemic faded away, possibly fueled by a strategic response by parties that absorbed these newly formed preferences in the ongoing dynamics of party competition.

On the contrary, individual preferences regarding the trade-off of rights and freedoms for public welfare followed a very different trajectory. The dynamics of voters’ preferences toward civil liberties were much more inextricably linked to the temporal and spatial severity of the pandemic threat. This suggests that voters did not update their beliefs about the costs and benefits of civil liberties, but simply adjusted their preferences to the circumstances. Moreover, these kinds of preferences are less easily absorbed within the dynamics of party competition, which is coherent with literature that has underscored mechanisms of individual vulnerability and security concerns as key drivers of voters’ consent to limit civil liberties.

Overall, the footprint of the pandemic threat on democratic preferences is deep and long-lasting. This is especially the case for technocratic preferences. Not all democratic attitudes in Spain had returned to pre-pandemic values four years later. Such a persistent change is likely to reshape some fundamental components of the democratic process, such as the selection of politicians in the near future, which paves the way for enduring, long-term legacies of COVID-19 on democracy. The political consequences of the pandemic are not over yet.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10035. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WO5QEX.

Acknowledgements

Francesc Amat acknowledges the funding from ‘La Caixa’ foundation under the Social Science Research Call program for the COVIDEMO project (LCF/PR/SR20/52550002) and Pandèmies-AGAUR. Albert Falcó-Gimeno acknowledges the financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the research project GTDEMO (PID2020-120228RB-I00). Jordi Muñoz acknowledges the financial support from ICREA under the ICREA Acadèmia programme. Andreu Arenas acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science (PID2020-120359RA-I00).