The burden of obesity has rapidly spread across the globe and it has been a major public health concern for the last few decades. It is estimated that, at present, approximately 14 % of the world’s population lives with obesity(Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Powis1). In parallel, evidence has been accruing on the detrimental impact of obesity on health. People living with obesity have an increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, some cancers, and musculoskeletal diseases(Reference Singh, Danaei and Farzadfar2–Reference Backholer, Beauchamp and Ball4). Obesity has also superseded smoking as the leading cause of death in some countries(Reference Ho, Gray and Welsh5,Reference Lopez and Adair6) . The high burden of mortality and morbidity attributable to obesity underpins its high cost for societies across the globe, not only due to healthcare but also loss of productivity(Reference Singh, Danaei and Farzadfar2,3,Reference Lu, Hajifathalian and Ezzati7) .

Due to rising concerns about the impact of obesity, in 2013 the WHO Member States committed to reducing the prevalence of obesity to 2010 numbers by 2025(8). However, no country will meet this goal if current trends persist. The prevalence of high BMI, globally, has increased by 1·86 % annually between 2010 and 2019(Reference Murray, Aravkin and Zheng9). The World Obesity Atlas 2023 predicts that 24 % of women and 19 % of men will be living with obesity by 2030, which equates to one billion people worldwide(Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Powis1). Current obesity statistics and the predicted trajectory of obesity represent a serious public health failure. The need for implementing comprehensive, multifaceted, policies is evident.

Sex differences in obesity trends and gender considerations

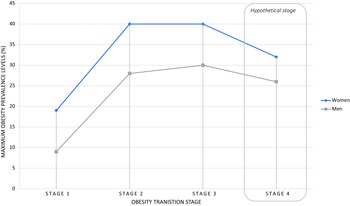

Sex refers to the biological characteristics that define humans as female/woman or male/men(Reference Coen and Banister10), a person’s sex interacts but is different to someone’s gender. Gender is socially constructed and concepts of gender vary by place and by time(Reference Coen and Banister10,11) . Both sex and gender interact with health(11). Sex differences in obesity trends are evident, with the largest increases in people living with obesity having happened in low- and middle-income countries, in low socio-demographic areas within high-, middle- and low-income countries, and for women in comparison to men(Reference Lobstein, Brinsden and Neveux12,Reference Jaacks, Vandevijvere and Pan13) . Sex differences in the expected trajectories of obesity are startling. For example, by 2035, 26 % of women in low-income countries are predicted to be living with obesity, compared to 11 % of men(Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Powis1). The increasing prevalence of obesity globally has been characterised within an obesity transition framework(Reference Jaacks, Vandevijvere and Pan13). This obesity transition was informed by trends witnessed in the 30 most populous countries comprising approximately 77·5 % of the world’s total population and is characterised by 4 stages, Fig.1. The stages are sequential, with Stage 1 characterised by a higher prevalence of women living with obesity than men and a higher prevalence for people with a higher v. lower socio-economic status. Stage 2 shows a large increase in the number of people living with obesity for both women and men, with the difference in prevalence between women and men becoming less, albeit still higher for women and people of higher socio-economic status. Stage 3 is characterised by increasing numbers of people of low socio-economic status living with obesity (surpassing those of higher socio-economic status) and potential stabilisation of obesity prevalence for women. Stage 4 is reserved for characterising declines in obesity prevalence; however, this stage is still hypothetical as no country has achieved the goal of reversing obesity trends.

Fig. 1 Obesity transition pathway by sex, based on data published by Jaacks et al(Reference Jaacks, Vandevijvere and Pan13)*. *Maximum obesity prevalence levels have been plotted, at different stages of the obesity transition framework, based on data from the thirty most populous countries globally (data published by Jaacks et al, 2019(Reference Jaacks, Vandevijvere and Pan13))

In line with differences in obesity prevalence globally, having a high BMI is within the top five leading causes of death for women, but not men. Having a high BMI equated to 9·8 % of all female deaths (2·54 million deaths) making it the 5th leading cause of death for women in 2019 (first was high systolic blood pressure; second, diet-related causes; third, high fasting plasma glucose; fourth, exposure to air pollution)(Reference Murray, Aravkin and Zheng9). For men, the corresponding leading causes of death were smoking, high systolic blood pressure, diet-related causes, air pollution and high fasting plasma glucose(Reference Murray, Aravkin and Zheng9). For both women and men, high BMI influences the risk of other leading causes of death (for example, having a high BMI is related to increases in blood pressure and fasting blood glucose), illustrating the potential for compounding benefits from reducing the prevalence of high BMI at a population level. While obesity shows clear sex difference in trends, other common cardiovascular risk factors do not. For example, a study across 16 years of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data found that hypertension, smoking and diabetes were similar between women and men and, while BMI increased for both women and men, the increase was greater for women(Reference Peters, Muntner and Woodward14).

Obesity can be defined both as a multifactorial disease and a significant risk factor for other diseases(Reference Bray, Kim and Wilding15). There are many factors that predispose to obesity, including genetic, sociocultural, behavioural and environmental factors(Reference Bray, Kim and Wilding15). While individual factors, such as our sedentary lifestyle, taste preferences and personal choices, may have contributed to the obesity epidemic, the importance of environmental/structural factors has been increasingly recognised. Thanks in part to globalisation, the so-called ‘obesogenic’ food environments have become more common worldwide and are even reaching remote communities who for centuries engaged with a healthy lifestyle and lived in harmony with the natural environment(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza16). These obesogenic food environments are characterised by easy access to energy dense, highly palatable foods with poor nutritional value and increasing portion sizes of these foods(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza16–Reference McCrory, Harbaugh and Appeadu19).

Given sex differences in the prevalence of obesity globally, it is plausible that food environments interact with other societal factors to underpin the sex and gender differences in obesity prevalence. Given failures in halting the exponential increase in obesity, and its disproportional burden for women, the aim of this review was to collate evidence on sex and gender consideration in obesity risk and discuss the need for gender-responsive food policy and interventions to reduce the burden of obesity equitably.

Biological considerations and obesity trends

There are biological reasons that may predispose women to a greater risk of obesity, requiring the need to incorporate sex and gender considerations in obesity prevention strategies.

Biological reasons for sex differences in obesity trends

First, Kaisinger et al.(Reference Kaisinger, Kentistou and Stankovic20) identified genes associated with sex- and age- specific obesity risk. They found female-specific associations between rare variant burden in three genes and obesity, where loss of function had effect sizes of up to 8 kg/m2. Second, different life stages are associated with different fat storage patterns and weight gain, specifically for women. During childhood, boys tend to have a higher prevalence of obesity than girls(Reference Shah, Cost and Fuller21), but this flips during puberty and adulthood(Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Powis1). This inversion corresponds with changes in levels and ratios of sex hormones, specifically an increase in oestrogen(Reference Cooper, Gupta and Moustafa22). However, excess weight tends to be stored in less harmful ways in women than in men, with storage of fat as subcutaneous adipose, particularly around the hips and thighs, whilst in men excess fat tends to accumulate in visceral and ectopic tissue(Reference Tramunt, Smati and Grandgeorge23). Although fat stored as subcutaneous adipose tissue is thought to be ‘protective’ to some extent, excess weight is still associated with increased risk of diseases like musculoskeletal diseases and heart disease in women(Reference Tramunt, Smati and Grandgeorge23,Reference Peters, Bots and Woodward24) . Furthermore, while some weight gain is expected and is considered healthy during pregnancy (11–16 kg for people with a ‘normal’ BMI, 7–11 kg for people who are overweight and 5–9 kg who are living with obesity)(25), research has shown that expectant women who gain weight in excess of recommendations retain an additional 3 kg of weight three years post pregnancy(Reference Nehring, Schmoll and Beyerlein26). However, excess weight gain during and following pregnancy may not be purely biological, with evidence suggesting that men also gain and retain excess weight with the transition to parenthood, albeit this is an under-researched area(Reference Saxbe, Corner and Khaled27). As women age, and particularly during menopause, fat storage patterns change. This is thought to be linked to a decrease in energy expenditure, an increase in food intake and deceasing oestrogen levels, changing the androgen to oestrogen ratio(Reference Moccia, Belda-Montesinos and Monllor-Tormos28). It is of note that the risk of obesity-related diseases increase for women during and after menopause(Reference Mauvais-Jarvis, Clegg and Hevener29), with specific risk associated with age, for example, mid-life obesity (categorised as 45–65 years) is a risk factor for dementia later in life(Reference Livingston, Huntley and Sommerlad30,Reference Kivimäki, Luukkonen and Batty31) .

Sex differences in nutritional requirements

Given differences in body composition and requirements during life stages, women and men have different nutrition requirements. In general, women require less energy intake than men, due to being generally smaller in body size and having a lower muscle mass(Reference Gibson32), this results in dietary recommendations being different, for example in the UK energy recommendations are 8400 kilojoules per day for women v. 10 500 for men(33). Due to men having higher energy requirements, some vitamin and mineral needs are greater on an absolute scale than women. However, during reproductive years, women have increased requirements for iron and, during pregnancy and breast-feeding, women require more folate, iodine and choline. With menopause, women’s requirements for Ca also increases, as drops in oestrogen increase the risk of osteoporosis(Reference Khan, Alrob and Ali34). These different requirements result in sex-specific dietary guidelines.

Sex differences in taste preference and response to food cues

There is evidence of sex differences in hormonal and neural influences on taste perception, satiety and food cues(Reference Martin and Sollars35–Reference Haase, Green and Murphy38). A review by Martin and Sollars(Reference Martin and Sollars35) consolidated information on sex differences in gustatory function, finding that receptors for sex hormones are prominent in several nuclei associated with central gustatory pathways, which may mean that sex hormones modulate taste processing. In particular, studies have found that oestrogen modifies taste-elicited activity(Reference Martin and Sollars35). There is some evidence that women are more responsive to sweet taste, and that, independent of hormone status, women and men have different neural responses to salty, sour and umami taste(Reference Haase, Green and Murphy38). Collectively, these differences in gustatory function may relate to evidence that shows differences in food preferences, with women more likely to prefer sweet, energy dense snack foods, whereas men tend to prefer savoury foods(Reference Manippa, Padulo and Van der Laan39,Reference Wardle, Haase and Steptoe40) . In addition, in comparison to men, women show higher neural responses to visual food cues(Reference Chao, Loughead and Bakizada37), which may further influence food behaviour.

Therefore, there are biological factors that may predispose women to a greater risk of obesity. However, we hypothesise that the food environment exacerbates any biological underpinning for differences in obesity risk and disparities in burden between women and men.

Gendered responses to food environments

According to Swinburn et al., food environments refer to ‘the collective physical, economic, policy and sociocultural surroundings, opportunities and conditions that influence people’s food and beverage choices and nutritional status’(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Vandevijvere41). Most people now live in obesogenic food environments(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza16), in which obesity is a normal physiological response to the overabundance and heavy marketing of highly palatable and energy dense food. There are several reasons why obesogenic environments may be having a greater impact on women than men, including food industry influences and the rise of ultra-processed foods having a potentially greater detrimental effect on women’s health in comparison to men, external factors influencing food security in a gender-specific manner, and gender roles and responsibilities in relation to paid and unpaid labour.

Food industry influences and the rise of ultra-processed foods

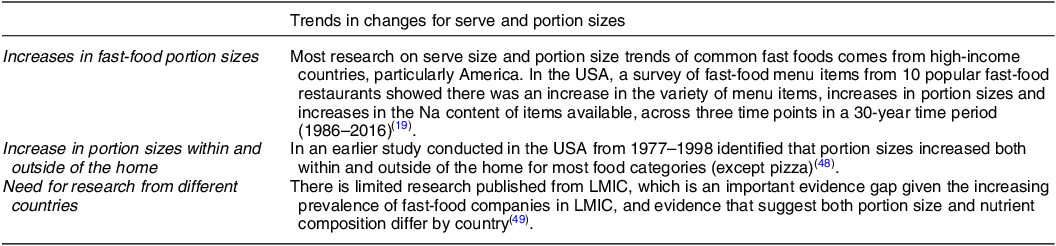

One of the biggest changes over the past years has been the rise of ultra-processed foods(Reference Lawrence and Baker42,Reference Baker, Machado and Santos43) . Ultra-processed foods have become staples of western diets and western culture, with evidence of increased consumption for women and men over the past two decades(Reference Juul, Parekh and Martinez-Steele44). There is building evidence that ultra-processed foods have detrimental health effects, and increase the risk of weight gain, independently of the nutritional composition of the food(Reference Hall, Ayuketah and Brychta45,Reference Monteiro and Cannon46) . A handful of companies control the global food supply and are responsible for producing the bulk of ultra-processed foods available on the market today, these companies have been increasing their reach and hold within low- and middle- income countries (LMIC)(Reference Baker, Machado and Santos43,Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro47) . Ultra-processed foods, and fast foods, also often come in standardised portions (Table 1). These ‘standardised’ portion sizes of preprepared foods have been increasing in recent years and it is known that people eat more of the food provided to them as the portion size increases(Reference McCrory, Harbaugh and Appeadu19,Reference Dunford, Webster and Woodward49,Reference Young and Nestle50) . It is likely that increasing portion sizes of prepared, and particularly highly palatable ultra-processed food, has increased the risk of overeating and, therefore the risk of weight gain, more so for women than men.

Table 1. Summary of increasing portion sizes of common ultra-processed and fast foods

Another way that food companies may be influencing consumption in a gender-specific manner is through the marketing of products. Advertising by mass social media often builds on social and cultural norms, in ways that reinforce ‘traditional’ gender stereotypes(Reference Ward and Grower51–Reference Royo-Vela, Aldas-Manzano and Küster54). Although a scoping review(Reference Castronuovo, Guarnieri and Tiscornia55) found evidence of gender-targeted food marketing aimed at children and adolescents, evidence is lacking for adults. In addition, the effect of exposure to gender-targeted food marketing on actual food intake by gender remains unknown. While the research is limited in the food marketing space, use of gender-targeted marketing is commonly used by other industries. McCarthy et al. released a call to action to ‘empower women to cast a spotlight on the harms from the commercial determinants of health’(Reference McCarthy, Pitt and Hennessy56). To support this call, they provided a plethora of examples of how harmful industries, including tobacco, alcohol, gambling and firearm industries have used marketing tactics to target and increase consumption of products by women, through playing to gender stereotypes and focusing on perceived insecurities(Reference Feeny, Dain and Varghese57–Reference Bosma, Giesbrecht and Laslett60). There are also documented examples of where these industries have actively gone against the interests of women, for example, the alcohol industry by underplaying the associated risk with breast cancer(Reference Petticrew, Maani Hessari and Knai61) and actively opposing pregnancy warning labels on alcohol products(Reference Heenan, Shanthosh and Cullerton62). While not covered by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Pitt and Hennessy56), ultra-processed packaged foods are a potentially harmful commodity from an industry that follows a similar play book of marketing tactics common to harmful industries, like tobacco(Reference Brownell and Warner63–Reference Mialon65).

Gender roles and responsibilities in relation to paid and unpaid labour

In 1993, Barry Popkin published his essay ‘Nutritional Patterns and Transitions’ characterising the stages of diet change witnessed globally(Reference Popkin66). Popkin discussed how this nutrition transition contributed, and will contribute, to the burden of non-communicable diseases, and related risk factors, including obesity. A component of this transition was ‘changes in socioeconomic structure led to changes in women’s roles and to shifts in dietary patterns’, implying that the move of women into the ‘formal’ workforce has an impact on dietary patterns at a population level(Reference Popkin66). Many women still tend to be the main gatekeepers for the nutrition of families, in addition to themselves, and women have a greater burden of household activities (such as child caring/rearing, cooking and cleaning) in comparison to men, irrespective of ‘formal/paid’ work commitments(Reference Doan, Thorning and Furuya-Kanamori67), sometimes referred to as a ‘double shift’. The ‘double shift’ phenomena is not unique to high-income countries, for example in qualitative studies conducted in Fiji, we identified that women retained responsibilities for nutrition of the family, even though most were in the formal/paid work force and working similar, or more, hours than male partners(Reference McKenzie, Waqa and Hart68). The economic/work transition has occurred in parallel to increasing availability and affordability of convenience foods (such as pre-packed foods, snack foods, take-aways/fast foods). The majority of these foods are ultra-processed foods, high in energy, fat, salt and sugar, yet they have become an easy option to address the need to feed the family in face of competing demands from work and personal duties. Excess consumption of these foods increases the risk of living with overweight and obesity(Reference Lawrence and Baker42,Reference Pagliai, Dinu and Madarena69) , and as set out earlier, there is likely an excess risk for women.

External factors that affect food security

In the early 2000s an evidence review of dietary causes of obesity found that there was ‘probable’ evidence to support adverse social and economic conditions in high-income countries as a risk factor for obesity, particularly in women(Reference Swinburn, Caterson and Seidell70). Multiple global crises have created adverse social and economic conditions(Reference Robinson71), and these impact on food systems, including climate change, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Food security, both chronic and acute (in response to an event, for example natural disasters), impacts women more than men(Reference Das, Kasala and Kumar72,Reference Broussard73) . Women are more likely to experience food insecurity and poverty for a number of factors. For instance, building on gendered roles and responsibilities previously illustrated, women tend to be employed in precarious conditions and hence be more vulnerable than men to any economic crisis that results in job insecurity. There is also evidence that women are likely to prioritise feeding their families in detriment of feeding themselves(Reference Lawlis and Jamieson74). Women experiencing food insecurity may increasingly rely on cheaper ultra-processed foods, which then predisposes them to consuming excessive energy intake and lacking essential nutrients for health, such as vitamins, minerals and fibre(Reference Moradi, Mirzababaei and Dadfarma75). In addition, women tend to have a lesser voice in national planning to mitigate effects of new challenges(Reference Bryan, Ringler and Lefore76). Therefore, adopting a gendered lens when developing food policy is critical to ensure that women are not disadvantaged(Reference Bryan, Ringler and Lefore76).

Discussion - addressing the burden

From our review of the literature, we suggest that the gendered influences within current food environments impact on the individual, influencing their food preferences, choice and overall energy consumption. These build on what might be sex differences in taste preferences and fat storage mechanisms and likely mean that women are at a greater risk of obesity within the obesogenic environment.

At a global level, there is some recognition of the need for a focus on gender in the response to the obesity epidemic. In August 2021, the WHO released ‘Draft recommendations for the prevention and management of obesity over the life course, including potential targets’(77). Sex and gender factors related to the burden of obesity were mentioned in terms of a commitment from policy makers to gender equity, the inclusion of gender equity considerations in health care and to focus on reducing gender stereotypes and the impact of these stereotypes on care for obesity. These guidelines and recommendations set a standard for governments globally to focus on creating gender-responsive food and health policies for obesity reduction. However, from our previous work we have seen that broad goals around ‘gender equality’ are not sufficient on their own, and that sex and gender considerations need to be included in ways that are context-specific, actionable and measurable(Reference McKenzie, Waqa and Mounsey78,Reference Wainer, Carcel and Hickey79) . We hypothesise that sex and gender considerations could be included in several ways, as will now be outlined.

Government commitment, policy setting and policy implementation

Addressing the obesity epidemic at a population level, and any gender disparities within this, requires addressing the structural factors involved in obesogenic environments. However, to date, many governments, particularly in high-income countries, have put emphasis on ‘individual empowerment’ when it comes to obesity(Reference Backholer, Beauchamp and Ball4,Reference Brookes80) . Although education on healthy eating and physical exercise are important, they are insufficient unless barriers that prevent people from adopting healthy lifestyles are removed by structural interventions. In the same vein, medical treatments for obesity, such as semaglutide(Reference Wilding, Batterham and Calanna81,82) , should not be seen as a silver bullet that will fix the longstanding obesity problem at a population level. Instead, at national and international levels, food policy can dramatically change the obesogenic environment and, particularly, address the key factors that have a disproportionate impact on women(Reference Swinburn83). For example, government could regulate how and what foods are marketed, the portion size of packaged/prepared food and nutrient composition of foods deemed appropriate for sale based on nutrient content(84). While such interventions will aid the creation of healthier food environments, policies that influence gender equality within societies more generally are also likely needed to address the root causes of disparities in obesity prevalence. For example, there is evidence that where laws and policies made primary education free, and/or safe guarded paid parental leave significantly improved women’s health(Reference Heymann, Levy and Bose85). We have established that countries with higher levels of gender equality, as measured broadly across several societal domains (e.g. education, economy, politics), have better life expectancy for women and men(Reference Pinho-Gomes, Peters and Woodward86) in comparison to counties with lower levels of gender equality. While evidence relating these factors to obesity directly are limited we hypothesise that interventions that encourage gender equity more broadly will also reduce the obesity burden.

It is crucial that policy implementation avoids perpetuating women’s disadvantage, which has been the norm for the past centuries. Inherent to this is the need for representation of women in decision-making, and making sure women’s voices are heard. According to data from UN Women and the Inter-Parliamentary Union, in January 2023 only 22·8 % of Cabinet Ministers were women, globally, with women making up just 26·5 % of Members of Parliament(87). In addition to our previously mentioned analyses which looked at gender equality more broadly(Reference Pinho-Gomes, Peters and Woodward86), an analysis of 49 European countries found that greater female participation in social and political life specifically was associated with less inequalities in self-reported health, along with fewer disability-adjusted life years lost for both women and men(Reference Reeves, Brown and Hanefeld88).

Further, there is a need for collecting and analysing by sex and gender throughout a policy implementation cycle to enable adjusting for unintended and unpredicted consequences for women, men and people of other gender identities. There are numerous pre-existing tools and frameworks to facilitate this, for example the WHO Gender Analysis Tool(89,Reference Morgan, George and Ssali90) . Such tools can be applied within frameworks designed for monitoring the food environments within countries, an example being the modules within the ‘International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) Research, Monitoring and Action Support’ (INFORMAS Network)(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Vandevijvere41).

Food environments - food industry, outlets and restaurants

There is a social responsibility for the food industry to create and supply food that is nutritious and safe for consumption. Food industries that have the largest market share focus on the production of ultra-processed foods, with growing evidence that these foods are detrimental to health at the levels of current consumption(Reference Lawrence and Baker42,Reference Pagliai, Dinu and Madarena69) and that they can be addictive(Reference Gearhardt, Bueno and DiFeliceantonio91). Evidence to date suggests that the greatest improvements in food environments are facilitated by mandated changes, with voluntary efforts having limited influence and limited compliance(Reference Galbraith-Emami and Lobstein92,Reference Trieu, Coyle and Afshin93) . In line with government level policy setting there is the opportunity to regulate smaller portion size and serve sizes in prepackaged foods (with corresponding decrease in price of these products). From a food retailer perspective, there is scope to offer a range of serve sizes at different price points. Some fast-food chains have done this, albeit the base, or ‘smallest’, serve size is often larger than needed(Reference Young and Nestle50). While more research is needed, there is an opportunity to learn from action against harmful industries and the gendered marketing tactics used. Most likely, more protection around unhealthy food marketing and the targeting of people based on gender stereotypes is needed in addition to current calls for food marketing restrictions based on age(Reference Taillie, Busey and Stoltze94).

There is also the possibility for gender-targeted interventions within food environments. Experiments with ‘nudging’, or choice architecture, have been shown to be effective in aiding people to choose healthier options, for example by using interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labelling and by making healthier choices more convenient through positioning in supermarkets. Reviews of nudging experiments are limited in their assessment of gender influences on choice(Reference Laiou, Rapti and Schwarzer95,Reference Bucher, Collins and Rollo96) ; however, given that women may be more likely to read front-of-pack labels and are more likely to be the main shopper for households, it is likely that there are gender differences(Reference Su, Junmin and Hannah97,Reference Nieto, Jáuregui and Contreras-Manzano98) . Finally, in line with front-of-pack labelling claims, there is the opportunity to investigate sex-specific claims and guidelines based on requirements. Nutrient profiling and corresponding nutrition labelling are based on a ‘reference person’, in most cases this is an average of energy requirements between women and men, so there is the possibility of looking at nutrient profiling (and subsequent labelling) based on sex-specific requirements.

Conclusion

Given the current burden of obesity and predicted trends, there is a need for structural approaches that tackle the food environment currently fuelling the obesity epidemic. Food systems need to be considered from gendered lenses to reduce the burden of obesity equitably. This means that policies relevant to diet and obesity need to be designed to be gender-responsive and transformative, with their implementation monitored for any sex or gender differences. Importantly, both women and men should be involved in the design, implementation and monitoring of food policies. There is also a need to focus on addressing research gaps, by conducting sex disaggregated and gender-sensitive research, to monitor the disease burden within countries. This research will provide a better understanding of the gendered impacts of food environments that we have explored in this review, providing best-buy interventions and policies for gender equitable obesity risk reduction within and across countries.

Financial support

BM is supported by a National Heart Foundation of Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship (APP 106 651). MW is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (APP1174120) and Program Grant (APP1149987). This work was presented through an invited speaker opportunity at the Irish Section Conference in June 2023, by BM. We would like to acknowledge the Nutrition Society’s financial support in attendance of this conference.

Conflict of interest

MW has been a consultant for Amgen and Freeline. BM and ACPG do not declare any conflicts of interest.

Authorship

The focus for the manuscript was conceptualised by M.W. and B.M. B.M. reviewed the literature and drafted the first version of the manuscript. A.C.P.G. and M.W. reviewed and provided input on multiple versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and agreed to the submitted manuscript. No person who would reasonably be considered an author has been excluded.