Poverty, diet and resilience

Even in high-income countries, people on low incomes are at risk of food poverty and low diet quality(Reference Mullie, Clarys and Hulens1). The past 20 years has seen increasing interest and concern about structural factors that promote unhealthy dietary patterns and undermine efforts to adopt healthy eating practices(Reference Monsivais, Thompson and Astbury2). Those on lower incomes tend to lack access to healthy foods(Reference Franco, Diez Roux and Glass3,Reference Hosler, Rajulu and Fredrick4) and epidemiological research demonstrates that diet quality follows a socio-economic gradient(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski5).

Socio-economic differences in diet contribute to health inequalities and are responsible for a range of adverse outcomes including obesity(Reference Nobari, Whaley and Crespi6,Reference Grøholt, Stigum and Nordhagen7) , type 2 diabetes(Reference Vinke, Navis and Kromhout8–Reference Agardh, Allebeck and Hallqvist10), CVD(Reference Psaltopoulou, Hatzis and Papageorgiou11,Reference Robinson, Carter and Ala-Korpela12) and malnutrition(Reference Zapata, Soruco and Carmuega13). Unhealthy diets and the adverse health outcomes they lead to are symptomatic of wider social inequalities(Reference Marmot14). There is an association between income, diet quality and food security(Reference Franklin, Jones and Love15,Reference Drewnowski and Darmon16) . Affording a healthy diet has become increasingly difficult in recent years in the context of rising living costs, falling incomes, welfare reform, insecure and low paid work, widening inequality(Reference Ashton, Middleton and Lang17). Economic recessions and, more recently, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic have amplified this trend and caused financial hardship which is further widening dietary health inequalities(Reference Nobari, Whaley and Crespi6,Reference Cummins, Berger and Cornelsen18) .

However, not all people equally exposed to adversity suffer equally(Reference Sanders, Lim and Sohn19). It is sometimes possible to take steps to mitigate adversity. For example, parents will compensate for neighbourhood-level deficiencies and may go to great lengths to overcome local constraints to physical activity or healthy eating when their children's health is involved(Reference Showell, Cole and Johnson20). This idea has been taken up in public health and framed in terms of ‘resilience’ to challenging or hostile conditions(Reference Houston21). The concept of resilience has long been part of preventive public health approaches and policies in low-income neighbourhoods(Reference Ziglio, Azzopardi-Muscat and Briguglio22). Dietary resilience describes the strategies used by individual and groups to overcome dietary obstacles presented by their circumstances and achieve a healthy diet(Reference Vesnaver, Keller and Payette23). Achieving dietary resilience is dependent upon consistency and certainty in particular factors at the household level, such as access to nutritious food at home and financial adequacy(Reference Vesnaver, Keller and Payette23,Reference Stephens, McNaughton and Crawford24) . Practices of resilience include prioritising health and healthy eating and developing cooking skills(Reference Beek L, van der Vaart and Wempe25).

Although the notion of resilience can be a framework for better addressing public health (nutrition)(Reference Wulff, Donato and Lurie26), there has been an emphasis on identifying personal risk and protective factors at the expense of exploring the role of the social, cultural and political contexts within which resilience occurs(Reference Canvin, Mattila and Burstrom27,Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker28) . Canvin et al.(Reference Canvin, Mattila and Burstrom27) present a framing of resilience as a process. Resilience can be understood as involving dynamic transitions: progressing from one state to another as individuals developed over time. The focus is on the contextual and structural factors that help or hinder resilience as a process – rather than focusing on individual traits(Reference Canvin, Mattila and Burstrom27). The present paper proposes that uncertainty about the social determinants of health (SDH) as a structural factor that has a detrimental impact on dietary health and hinders dietary resilience for those on low incomes.

Poverty, uncertainty and the social determinants of health

Poverty is dynamic and uncertain and, it has been argued, there are different types of poverty that people can move in and out of or, sometimes, get stuck in(Reference Wood29). Room(Reference Room, Gordon and Townsend30) describes this as a ‘snakes and ladders’ scenario in which people have contrasting trajectories of poverty marked by different opportunities, challenges, dangers and levels of agency(Reference Room, Gordon and Townsend30). It is those ‘types’ and experiences of poverty that are characterised by chronic uncertainty that have become of increasing interest to researchers considering the effects of poverty of health outcomes and behaviours, including nutrition and dietary health(Reference Whittle, Leddy and Shieh31).

Poverty is characterised by uncertainty. Those on low incomes tend to have less control over relationships and events about them. As a result, they are obliged to live more in the present and to discount the future(Reference Wood29). This can make it impossible to plan and perform strategies of dietary resilience. In particular, it is uncertainty about the SDH that undermines efforts to achieve a healthy diet. The SDH are ‘the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels’(32). These conditions include housing quality, transport, discrimination, neighbourhood safety, education, employment, income, welfare and the food environment. Uncertainty and insecurity is a pervasive and destructive feature of contemporary experiences of poverty that go beyond being on a low income(Reference Wood29). Insecure working conditions, punitive welfare regimes, increasingly casualised working conditions, widespread cuts to the funding of public services and growing levels of personal debt(Reference Cummins33–Reference Carney and Stanford35) have all contributed to this.

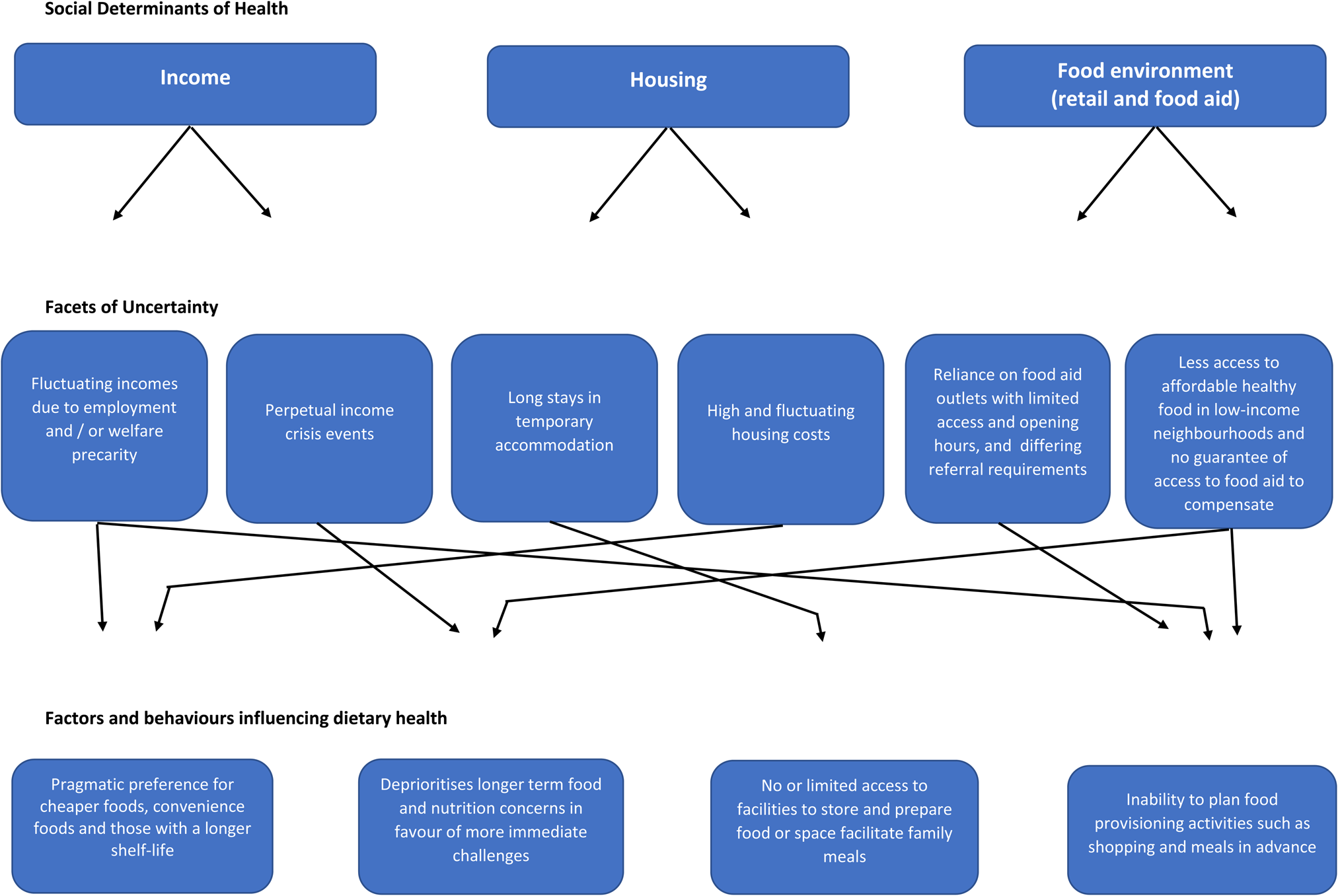

Chronic uncertainty about the SDH – such as dealing with insecure and inadequate housing conditions, or not knowing from week-to-week how much money you have to live on – often means a lack of agency and difficulty in engaging in behaviour change and health seeking behaviour. Healthcare professionals have long raised concerns about the corrosive health impacts of chronic uncertainty in terms of ‘chaotic lives’, ‘complex contexts’ and a ‘lack of stability’(Reference Tomlinson36). The topic has also been recognised across a range of disciplines and terminologies. Social scientists have framed this uncertainty in terms of precarity – referring to contemporary social and economic insecurity in wealthier nations that is driven by the post-industrial resurgence of insecure labour and shrinking welfare states. It has cumulative and negative impacts on health and well-being in the longer term, such as hunger and reduced access to health care, and can be understood as a structural vulnerability(Reference Whittle, Leddy and Shieh31). Material-need insecurities make ‘healthy choices’ and longer-term considerations about dietary health difficult or impossible to enact. They force people into short-termist and potentially damaging dietary practices(Reference Whittle, Leddy and Shieh31). This review brings together research that addresses dietary health with reference to uncertainty about the SDH in three fundamental areas: income, housing and the food environment (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Facets of uncertainty around the social determinants of health and implications for diet.

Facets of uncertainty about diet and the social determinants of health

Income uncertainty and diet

Income is, perhaps, the most fundamental SDH because it shapes overall living conditions, affects well-being and mental health and influences health-related behaviours, including dietary practices(Reference Mikkonen and Raphael37). Lower incomes are associated with less disposable income, which acts as a barrier to achieving a healthy diet(Reference Bertoni, Foy and Hunter38). Healthier, nutrient-rich foods tend to cost more compared to less healthy foods(Reference Aggarwal, Monsivais and Drewnowski39,Reference Darmon and Drewnowski40) . Poorer households can find themselves unable to afford enough food(Reference Griffith, O'Connell and Smith41), and the food that they can afford is typically energy dense and low in nutrients(Reference Dinour, Bergen and Yeh42). Unsurprisingly, those on low incomes are at greater risk of food insecurity(Reference Gundersen and Ziliak43–Reference Smith, Thompson and Harland45).

The challenges associated with low incomes are compounded when those incomes are uncertain and unstable. There is a growing trend in economic instability for those in low incomes, which is fuelling health and social inequalities for children and families(Reference Morris, Hill and Gennetian46–Reference Lambert, Fugiel and Henly48). Chronic financial uncertainty makes activities such as food preparation, meal planning and facilitating family meal times extremely difficult. In the longer term, these activities become deprioritised and occasionally abandoned altogether, especially when parents are in a perpetual state of crisis(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins49). Households experiencing income uncertainty, especially due to insecure work and welfare regimes, have multiple and conflicting constraints on their time as trying to secure a basic level of income under these conditions is very labour intensive and often requires them to be in different places and provide ‘evidence’ at short notice. Planning dietary behaviours in advance is, therefore, difficult. In order to mitigate this, these households tend to place greater importance on preparation convenience and a long shelf-life. Foods that are quick to prepare and last longer without spoiling make the most sense in this context(Reference Bruening, MacLehose and Loth50,Reference Nackers and Appelhans51) . Although this is a reasonable strategy for ensuring that money and food last longer when both are in short supply, it does mean that these individuals more frequently consume food high in fat, salt and sugar and consume less fruit and vegetables than those with more stable incomes and food security(Reference Drewnowski and Darmon16).

Strategies of short-termism and cost-reduction in the context of uncertain incomes can overshadow many aspects of self-care and render long-term health-related considerations such as diet seem unimportant(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins49,Reference Morton and Guthrie52) . Those experiencing financial uncertainty are very much aware of this trade-off(Reference Wolf and Morrissey47), of the necessity of sacrificing longer-term gains for short-term necessities(Reference Wood29). Polling research from North America reports that achieving financial security was a greater priority for those experiencing hardship than increasing their household income(Reference Wolf and Morrissey47). Income uncertainty creates dilemmas and difficult choices about food that have consistently negative implications for health, such as having to choose between paying for medication or food(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins49) and having choose between feeding yourself or feeding your children(Reference Hall, Knibbs and Medien53).

Housing instability and diet

Housing conditions are closely linked to income and represent a significant impact upon physical and mental health and well-being via factors including housing provision, quality, safety, (over)crowding and security(Reference Krieger and Higgins54,Reference Fierman, Beck and Chung55) . Housing is more than accommodation providing shelter. These spaces are homes where people raise families, socialise, keep their possessions safe, take refuge from the world and spend most of their time(Reference de Sa56). They are also where most of us store and prepare food. Housing and food are two of the biggest areas of expenditure for low-income households and are widely regarded as basic necessities(57,58) . In some cases, they can be competing priorities, spending on one means not having enough to pay for the other(Reference Kushel, Gupta and Gee59) or for other necessities such as clothing and transport(Reference King60). Knowles and colleagues'(Reference Knowles, Rabinowich and de Cuba61) qualitative research on the lived experience of these competing priorities explores how the chronic, extreme stress of economic hardship, including food and housing insecurity and basic needs trade-offs, is reflected in parent descriptions of experiences with depression, anxiety and fear. Parents described how adversity associated with the lack of access to food, lack of affordable housing and exposure to violence are negatively reflected in the behaviour and well-being of their children(Reference Knowles, Rabinowich and de Cuba61).

There is no standard definition of housing instability or uncertainty. Working definitions include frequently having to move home, difficulty paying the rent, spending more than half of household income on housing costs, being evicted and living in overcrowded conditions(Reference Ma, Gee and Kushel62). Homelessness or being made homeless through eviction are associated with a range of negative health effects, including low birth weight, increased hospitalisations, adverse mental health outcomes, increased risk of asthma and higher levels of food insecurity(Reference Cutuli, Herbers and Lafavor63–Reference Yousefi-Rizi, Baek and Blumenfeld66). People on limited incomes can feel forced by economic constraints to make their homes in unsafe environments in which they and their children are exposed to violence, crime and social isolation(Reference Knowles, Rabinowich and de Cuba61).

A specific relationship between housing instability and diet has yet to be established, although plausible mechanisms exist(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox67). In general, temporary and insecure housing can negatively impact health because people who feel they lack adequate control over their life circumstances, especially in terms of where they live and how they live, are at an increased risk of depression and physical illness(Reference Leng68). More specifically, the children of low-income families in rented accommodation are much less likely to show signs of undernutrition if their parents are in receipt of public housing subsidies, as compared to families that do not receive subsidies(Reference Meyers, Cutts and Frank69). Added financial security and certainty about housing status could be instrumental in improving diet and reducing food insecurity. Long-term stays in temporary accommodation can mean limited or no access to adequate facilities to store and cook food, inadequate space to eat together and increased reliance on food banks and other food assistance(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins49). Chronic housing instability can also hinder family meal routines and opportunities for social eating(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox67,Reference Mayberry, Shinn and Benton70) .

Uncertainty about food environments and diet

The term food environment refers to the collective physical, economic, policy and sociocultural surroundings, opportunities and conditions that influence people's food and beverage choices and nutritional status(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Vandevijvere71). They are the physical and social spaces in which uncertainties about the SDH converge and are translated into diets and dietary practices. Material conditions, including material need uncertainties, shape how people interact with their local food environments, the foods they obtain (either through retail or food-aid outlets) and the food choices they make. Unhealthy food environments are symptomatic of the interacting pathologies of low incomes, community disadvantage and the actions of the food industry(Reference Brown and Brewster72). Economically and socially disadvantaged groups are exposed to environments that may not support health eating, environments in which healthy food outlets are less accessible and less healthy alternatives are abundant(Reference Kraft, Thatcher and Zenk73).

For those on very low incomes, food environments are changing and becoming more uncertain. If current trends in food insecurity continue then the diets of low-income people may become characterised by the inclusion of significant amounts of donated and surplus food accessed via the third sector from outlets such as food banks and food pantries(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins74). Food-aid use is rising and the sector is now firmly established both in communities and as an increasingly regular source of food for those on low incomes(Reference Black and Seto75–Reference Lambie-Mumford and Green77). Those on low incomes can experience barriers in accessing both the retail and food-aid environments. Specifically, they may lack the financial resources to obtain all their food from the retail food environment, especially given that food tends to be poorer in quality and higher in price in low-income neighbourhoods(Reference Gosliner, Brown and Sun78). As a result, they may have to rely on food aid. But, this supplementary or ‘hidden’ food environment is not easy to access. Different outlets tend to operate very limited opening hours and can only be accessed by means such as referral, membership fees and subscription(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins74). There is no legal right to food-aid and access to can be dependent on local capacity and characterised by uncertainty. Food-aid outlets tend to open where there is volunteer capacity to run them and not necessarily where levels of food insecurity are highest. As a result, some areas – particularly rural and costal ones – can be underserved(Reference Smith, Thompson and Harland45,Reference May, Williams and Cloke79) .

Exemplar: crisis and diet

Public health and economic crises are known to impact disproportionately low-income and disadvantaged groups(Reference Álvarez-Gálvez, Rodero-Cosano and Salinas-Pérez80). The coronavirus pandemic (2020–2021) served to widen economic and health inequalities and amplified uncertainty about the SDH(Reference Perry, Aronson and Pescosolido81–Reference Abrams and Szefler83). The economic shock resulting from measures to contain the spread of the virus created further poverty and uncertainty for those on low incomes and problematised the complex strategies they used to feed themselves(Reference Kinsey, Kinsey and Rundle84). Access to food aid during the pandemic was made more difficult for some groups, as demand increased and contact with professionals who could provide referrals was limited by social-distancing measures(Reference Barker and Russell85). Research suggests that the pandemic and the associated mitigation measures served to amplify dietary health inequalities. Those who had security about the SDH, particularly income and housing, were able to improve their diets during ‘lockdowns’ and spend more time planning and preparing meals. Those experiencing uncertainty about the SDH had to contend with deteriorating dietary quality and difficulties accessing food(Reference Thompson, Hamilton and Dickinson86). In times of unprecedented change and disruption, population health researchers must reflect on how evidence is generated(Reference Monsivais, Thompson and Astbury2). The disruption caused by the pandemic brought renewed attention to diet and the SDH, particularly in terms of precarity and uncertainty(Reference Singu, Acharya and Challagundla87).

Directions for future research

Greater attention needs to be focused on the role of the SDH in shaping diet(Reference Monsivais, Thompson and Astbury2). Specifically, the cumulative negative impacts of uncertainty about the SDH need further attention because they place households in precarious situations: having little control over the conditions of their life; having to make constant and difficult trade-offs between their basic needs and foregoing long-term gains for short-term survival(Reference Knowles, Rabinowich and de Cuba61). In this context, maintaining a healthy diet becomes both more difficult and less of a priority. There are simply more pressing material needs to be addressed. Uncertainty about the SDH undermines the efforts and strategies used by those on low incomes to achieve dietary resilience. Research is needed to categorise household food-related resources. This is because interventions to build dietary resilience must be informed by a reliable assessment of capacity to be resilient on the part of the groups being exposed to the intervention(Reference Vesnaver, Keller and Payette23).

Dietary health can be compromised by coping strategies to mitigate chronic uncertainty. These strategies often necessitate prioritising food pricing and optimising food usage when making food choices, and sacrificing quality(Reference Vilar-Compte, Burrola-Méndez and Lozano-Marrufo88). This is not always enough to ensure that there is a sufficient amount (and certainly not sufficient quality) of food for the household. In which case, intermittent and even regular use of food-aid outlets such as food banks becomes a consistent necessity and strategy. At present, there is little research on how on-going food aid use figures in household food provisioning practices(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins49) or shapes local food environments(Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins74). Given that food aid is embedded and institutionalised in high-income countries(Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn89), exploring the longer-term dietary health implications of donated and surplus food must be a priority.

Financial Support

The author is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England (ARC EoE) programme. The views expressed are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

The author had sole responsibility for all aspects of preparation of this paper.