Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) is recognized as a key painter who blurred the division between history (allegorical) paintings and landscapes in the early seventeenth century. Throughout the sixteenth century, these two genres were taken as exemplifying a critical divide between Italian and Flemish conventions. During his stay in Italy (1600–1608), Rubens once refused to paint woodland scenes—typical of his native tradition—as a gift to the king of Spain (Gibson Reference Gibson1989, 83). However, later in his life—after coming back from Italy (1615–40)—he painted a series of landscapes in which we find a fusion and innovation of Italian and Flemish conventions. In addition, these works were not commissioned for churches or by patrons; Rubens painted them for the interior of his own houses. We may wonder about the morally creative conditions that enabled Rubens to revise the northern conventions of world landscape, which actually appear a bit awkward in terms of depicting nature. Thus, we should reconsider the significance of his landscape paintings for viewers in our times through reconstructing them in terms of signifying systems.

Between Oneself and Traditions: Intriguing Landscapes in Later Rubens

In these landscapes Rubens presents in the foreground a stylishly similar group of figures with variations in their positions, labors, and attributes (figs. 1, 2). When he was painting these between 1616 and 1619, he was also working on several history paintings, one of which is Adoration of the Shepherds, commissioned for the church of St. John in Mechelen (Shawe-Taylor and Scott Reference Shawe-Taylor and Scott2007, 134). In this work we find the same figure, a lady in a standing caryatid position, barefoot, and holding a cumbersome looking jar overhead (fig. 3).

Figure 1. A series of landscapes in later Rubens: The Farm at Laken, 1617–18 (left); Summer: Peasants Going into Market, 1618 (right); Winter: The Interior of a Barn, 1618–19 (middle). The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015.

Figure 2. Rubens, Landscape with a View of Het Steen, 1635. © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 3. Rubens, Adoration of the Shepherds, 1616–19. Musée du Louvre. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

In addition to baby Jesus, the six figures around the lady are so large that they occupy almost the whole painting, leaving the angels, oxen, and a dog at three corners and creating a rather crammed impression. The impressionistically painted wooden structures block our view, preventing us from seeing what is outside the barn. Rubens’s landscapes can be related to such a commissioned work as he gradually expanded the scale of landscape, reduced the size and number of figures, and managed to accommodate complete images of animals, either at rest or in motion. So it appears that these enticing landscapes (fig. 1) may also exemplify a highly personal style of history painting seen through the pleasant landscape of Rubens’s home country.

Sixteenth-century controversies over the compositions of pictorial space appear to have found a resolution in Rubens’s landscapes. First, he discards the geologically unconvincing rocks (which block the horizon), grotesque and elfish figures, fragmentary and unsystematic mounds of land, and, most of all, the eerie atmosphere characteristic of the northern tradition of world landscape (Weltlandschaft) (fig. 4).

Figure 4. Joachim Patinir, Landscape with St. Jerome (1515–24). Museo del Prado-Pintura, Madrid, Spain. Album / Art Resource, NY.

Second, unlike most Italian history paintings, in which the landscape stays in the background and appears subordinate to the prominent figures in the foreground, Rubens’s landscapes open up panoramic vistas into which viewers’ eyes may roam as freely and as far away as possible (figs. 1, 2). Third, the tiny but animated figures were observed in real life situations instead of being copied from Italian masterpieces or emblematic collections. Although there remain some traces of world landscape, for example, the high horizon, the contrast between light and shadow as well as the random placement of logs, Rubens has created a kind of “optical itineraries” (Melion Reference Melion1991, 11) that invite us to imagine the occurrence of allegorical stories set against the ebb and flow of peasant life and environment.

We may wonder why Rubens revised the convention of northern landscapes that had so impressed foreigners as woodlands or rocky mountains but that disconcerted him while he was in Italy. In addition to his long-term collaboration with Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), another connection that may well explain his revisions is his annotation of three books of Karel Van Mander’s Book of Painters (Het Schilder-Boeck, first published in 1604). He actually annotated a 1618 reprint of the work in which the first book was not included (Melion Reference Melion1991, xxiii). It is not certain whether Rubens turned to another reprint to read the first book, which contains the laws for bridging history paintings and landscapes. He must, however, have at least leafed through the life stories and working methods of ancient, Italian, and Northern painters contained in books 2, 3, and 4, respectively—the foundation on which Van Mander built his theory. Moreover, considering that the trait of rederijker (people who are enthusiastic about transforming poetic lines into visual images) was shared among several Flemish painters at the time (Gibson Reference Gibson1989), it can be enlightening to take the first book as a guide to Rubens’s landscapes.

In the tradition of literary humanism to which both Van Mander and Rubens subscribed, the idea of “invention” was defined as the governance of “order,” “arrangement,” and “ratiocination” of the activity of an aspiring artist. Images of “nature” were indispensable to the arts, which were judged and praised according to the discovery of novel thoughts in the composition (Richardson Reference Richardson1777, 58). Nevertheless, in the study of Dutch and Flemish paintings done in the seventeenth century, approaches like “iconography” and “iconology” have overtaxed viewers with the task of deep interpretation. Iconography is anchored in the didactic or moral lessons that are thought to have been apparent to viewers at the time but that are disguised to us today; iconology—although much beyond didacticism—tends to summarize paintings under the umbrella term of a certain philosophy or intellectual movement at the time (Panofsky Reference Panofsky and Paulsson1972; Adler Reference Adler1982; Sluijter Reference Sluijter, Freedberg and Vries1991; Westermann Reference Westermann2002). In order to appreciate Rubens’s landscapes painted just before the multiplication of genre paintings in the later seventeenth century, this article proposes to employ a different approach—“semiotics” cum “hermeneutics.” Such a composite approach aims to address certain referential illusions in art history while seeking to multiply ways of attributing and interpreting details that serve to enhance our pleasure in viewing and contemplating.

Between Semiotics and Hermeneutics: Iconic Signs, Referential Illusions, Cognitive Types, and the Interpretant

In the field of semiotics, paintings as well as other visual arts have been taken as a target in the controversy over whether it is legitimate to treat “icons” as signs.Footnote 1 Semioticians and philosophers have argued against the undifferentiated endowment of the functions and features of linguistic signs to visual icons. In order to break away from the constraints of linguistic concepts, some philosophers have refined notions about the degrees of similarity and quantified the amount of information carried by images in different media (Wallis Reference Wallis, Rey-Debove and Sebeok[1968] 1973; Goodman Reference Goodman, Foster and Swanson1970). However, the idea that images refer to, imitate, or resemble things in the world appears absurd to those who follow the Peircean and Greimasean sense of “iconicity.” According to Peirce, Greimas, and their followers, our making of images is a kind of mental quality or capacity, with which we constantly think over possibilities or potential developments. It is thus asserted that relating images to the world of concrete objects may not help generate an enlightening theory of art (Bierman Reference Bierman1962, 249).

The Peircean and Greimasean approach dispels the “referential illusion” by putting forward several features of iconicity: (1) the procedure of making sense out of linguistic signs is not applicable; (2) it is asymmetrical and constantly evolving in shaping ideas and possibilities; (3) it stands for itself and exhibits its own meaning, that is, it is self-referential (Bierman Reference Bierman1962; Eco Reference Eco[1976] 1979; Sebeok Reference Sebeok1976; Greimas and Courtés Reference Greimas, Courtés and Crist1982; Sonesson Reference Sonesson and Bouissac1998). Emphasizing the fact that logical semantics (based on the distinction between denotations and connotations) fails to hold good in defining iconicity and interpreting the visual arts, certain semioticians have suggested that we redefine icons as ways of modeling and representing the world which are more or less constrained by the specific societies or cultures from which they emerge (Greimas and Courtés Reference Greimas, Courtés and Crist1982; Bouissac Reference Bouissac, Bouissac, Herzfeld and Posner1986).

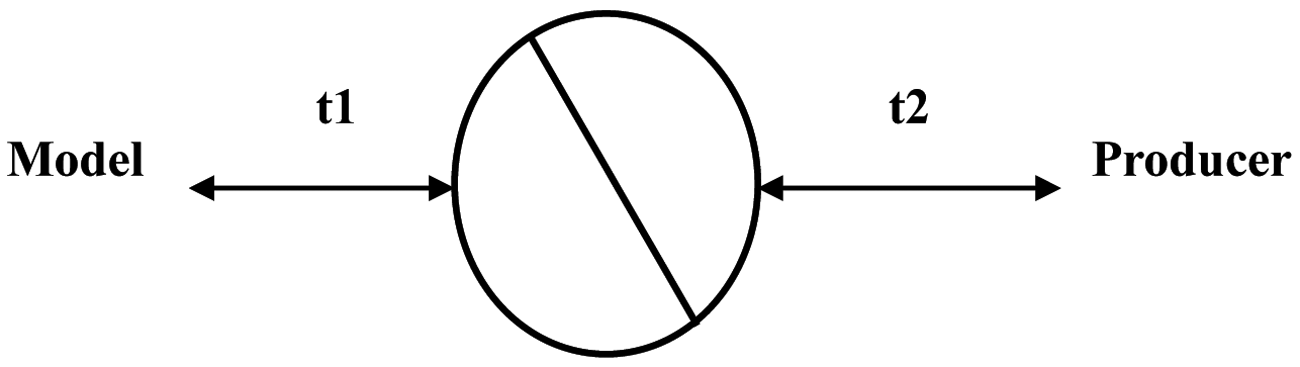

Debates developed in the 1960s and 1970s disclose a paradox in the nature of iconic signs: it is divided between the two extremes of being a similitude and a convention. In the early 1990s, the Belgian Groupe µ made a drastic move to explore visual perception as an independent domain from that of language cognition: they declared that we abolish an excessive use of linguistic models in the study of visual arts and seek to redefine the nature of linguistic phenomena based on a thorough study of human perception (Groupe µ Reference Groupe1992, 147). Moreover, they accused Umberto Eco of having wrongly simplified the relation between images and objects (129–31, 142). Instead of dismissing such relation as being merely referential (which they thought happens only in the designating function of natural languages), they justified it as a two-way “transformation” (132–33; fig. 5). On the one hand, producers select (t2) some features in their models and incorporate (t1) them into their iconic signs. On the other hand, for viewers to make good sense, they have to interpret the signs in two ways: the one (t2) leading them back to the cognitive types of producers; the other (t1) to the conventional ways of transforming objects.

Figure 5. Production of iconic signs (Groupe μ Reference Groupe1992, 132; in English translation)

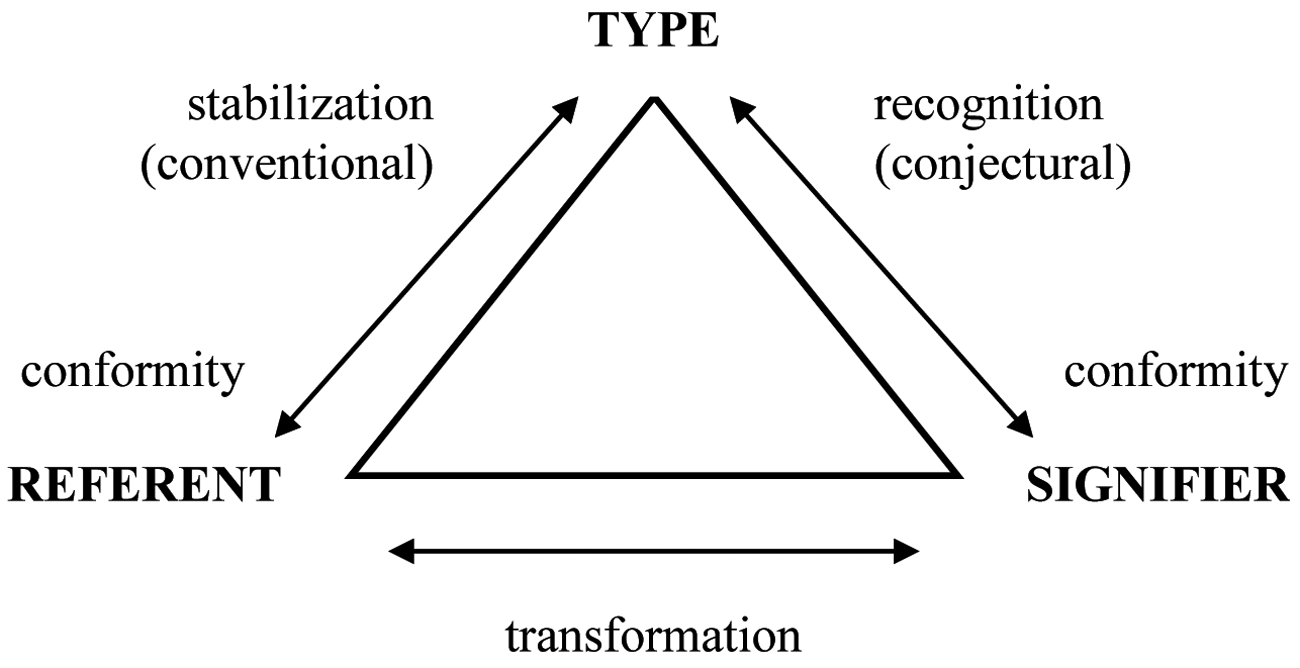

In addition to such two-way postulations, Groupe µ proposed a triadic model in which “types” govern the transformation of objects into “referents” (or cultured objects) and that of images into “signifiers” (or collections of visual stimuli) (fig. 6). They emphasized the fact that there are more transparent and stable links between types and referents than those between types and signifiers: referents can expand the paradigms (repertoires) of types while signifiers are so ambiguous—much more coded—that it takes conjectures to recognize types through them (Groupe µ Reference Groupe1992, 140–41). By introducing types into the structure of iconic signs, Groupe µ put forward a balanced view on the collaboration between our innate capacity and evolving perceptions. Iconic signs are dynamic and even rhetorical since artists negotiate between their experiences of objects and their knowledge of paradigms in their own styles—the former open up possibilities for inventions while the latter may set limits upon them.

Figure 6. The model of iconic signs (Groupe μ Reference Groupe1992, 136; in English translation)

Later in the 1990s, Eco responded to Groupe µ and the rising cognitive sciences in a cynical tone: he claimed that it is unfounded to take “cognitive types” as a self-evident starting point because their nature has been made a black box (Eco Reference Eco and McEwen[1997] 2000, 131–34, 138). He suggested that we follow his commonsense approach in order to discuss cognitive types (CTs) as constructed end products in the same fashion as trying to describe some unknown species. His approach introduced another term, “nuclear contents” (NCs), into the process of discovering CTs. According to Eco (139), NCs manifest themselves as our multimedial presentations—through drawings, gestures, sounds, and words, and so forth—of something. These perceptual experiences or memories are made public when a human subject manages to convey them to another. Therefore, contrary to what scientists have postulated—some kind of biologically specific devices are functioning in us all the time—according to Eco, CTs remain in absentia most of the time. It is not until subjects start to communicate, to recognize, and to refer felicitously—in order to suit circumstances—that CTs come to be in presentia. Following this argument, Eco reversed the fortune of CTs from being a black box to a white one, with which subjects make visible and tangible their treasured ideas and help each other imagine things and formulate ideas. This notion led to the assumption that Eco had taken a realistic turn in the 1990s concerning his definition of iconic signs. However, a more critical look into his statements reveals that he actually favored a kind of NCs which is not limited to any perceptual experiences or semioses but can be “transmitted” across cultures (Eco Reference Eco and McEwen[1997] 2000, 138, 166, 175–76). Thus, it seems that Eco has undermined his argument—the presence of CTs is governed by NCs—and thus revived the controversy that he and others had initiated in the 1960s and 1970s: iconic signs are once again detached from immediate physical environments and the actual world.

Eco’s efforts are consistent since he has always argued that referents are far from concrete objects—as opposed to Groupe µ, which retained the binary distinction that types are conceptual and categorical while referents are concrete and physical. Even if referents have to be rigid designations in extreme cases, they simply constitute the starting point of a larger and more evolving action, which is about making contracts—establishing “on trust” relationships—with those who have before used certain signs in one way or another (Eco Reference Eco and McEwen[1997] 2000, 293). Moreover, instead of feeling uncertain about and even arguing over the objects referred to, viewers and speakers should examine the laws of modeling and representing that have evolved between communities: referents are about conceptual and legal domains where subjects—across times and spaces—negotiate the uses of certain signs. With such an enlarged notion of referentiality, Eco recognizes two prospects of iconic signs: (1) they follow and bring together certain laws and traditions; (2) they are effective in forming discourses and arguments, and even creating certain effects of meaning and truth (Eco Reference Eco and McEwen[1997] 2000, 420). Iconic signs redefined in light of a subtle understanding of indexicality stop relying on objects referred to as the only legitimate source of meaning; it is rather meaning—at its multiple levels and in different contexts—that guides viewers and speakers into applying laws and principles: “It is not possible to explain how we refer to reality if we do not first establish how we give meaning to the terms we use” (420).

Semiotics does not take meaning as something given or something that can be easily read from the surface. It rather encourages explanations that go deeper into the layers of a text in order to discover its latently conflicting discourses. Hermeneutics and iconography-based iconology, on the other hand, takes intuition, empathy, pre-understanding, and certain philosophical stances as primary conditions in dealing with a text. These approaches stand opposed to following prescribed procedures to guide explanation and to vary understanding (Greimas and Courtés Reference Greimas, Courtés and Crist1982, 187–88). Paul Ricœur in the late 1980s and early 1990s endeavored to unify semiotics and hermeneutics into one harmonious whole, advocating the necessity of generating meaning and understanding in accordance with laws and procedures. As he declared, the benefit is to transform explanation and understanding as a matter of “pedagogy”: a process or reconstruction made up by intermediary stages, which we can repeat for ourselves and teach to others (Ricœur Reference Ricœur1990, 117). Likewise, Eco took a similar turn in the way that he has made CTs—laws and referents—so stable and tangible that they function like “systems of instructions” with which interpreters learn how they can manage texts (Eco Reference Eco and McEwen[1997] 2000, 168, 171).

Actually, we cannot afford to lose sight of either portion—the world or our mind—while engaging in the task of interpreting. Peirce in fact revised the doctrines of introspective psychology, which advocated that we could know something intuitively without paying attention to objects in the world. He rather promoted a strong sense of observing and perceiving the outer world with his notion of the “interpretant,” which is already an interpretation and yet precedes emergent signs (Peirce Reference Peirce and Hoopes1991). Such a notion serves to mediate our perceptual and enactive ends: we have an innate capacity or schema to form mental images of our own, and further still we seek to develop them in tune with our social and cultural environments. Precisely, we need to conceptualize some kind of two-way interpretant—the private mind that shows the enthusiasm of developing endless semiosis; the public mind (such as the notion of nuclear contents defined by Eco) that encourages investigations into and negotiations between contradictory explanations—so as to fruitfully revise certain unpolished readings. According to Ricœur, such interplay can be seen as the double principle of “difference and reference” that serves to unify our mind and the world while we are carrying out the semiotic cum hermeneutic inquiry ([1969] Reference Ricœur and Ihde1974, 261). Our “suspension of the natural relation to things” enables us to breed differential relations that constitute a semiotic system in our mind (260). Nevertheless, such a system remains limited—merely a gathering of contemplations—unless we make efforts to associate the system with the world: to refer felicitously and to stage dialogues between intriguing details (260–61). Our application of certain laws and principles would definitely give rise to unforeseen meaning or signification that serves to update any semiotic system we are establishing.Footnote 2 Basing our development on the methodological convergence between semiotics and hermeneutics, we move on to explore intriguing details found in Rubens’s landscapes.

Between Art and Play: Widening Our Horizons, Unifying Patterns, and Gaining Understandings

An iconographic viewpoint regarding the stylization of milkmaids in Rubens’s later works affirms the painter’s transformation of the genre of ill-matched lovers: the crudely moralistic overtones of the genre have been converted into states of rural plenty, genuine affection, and heavenly blissfulness as revealed in his landscapes. Such a renewal is also believed to correspond to a very personal aspect in Rubens’s life—his second marriage with the much younger Helena Fourment and his joy of regaining the pleasures of the flesh (Belkin Reference Belkin2009, 264, 268). This viewpoint is adequate in the way that it seeks to bridge the gap between art and life. However, in light of the form-giving principle (Gestaltungsprinzip), or more precisely, the formation of an iconic sign (Groupe µ Reference Groupe1992; Pächt Reference Pächt and Britt1999), an artist already interpreted and transformed what he has experienced in accordance with some innate organizing principles; that is to say, the link between art and real life is always obscure (Groupe µ Reference Groupe1992, 136).

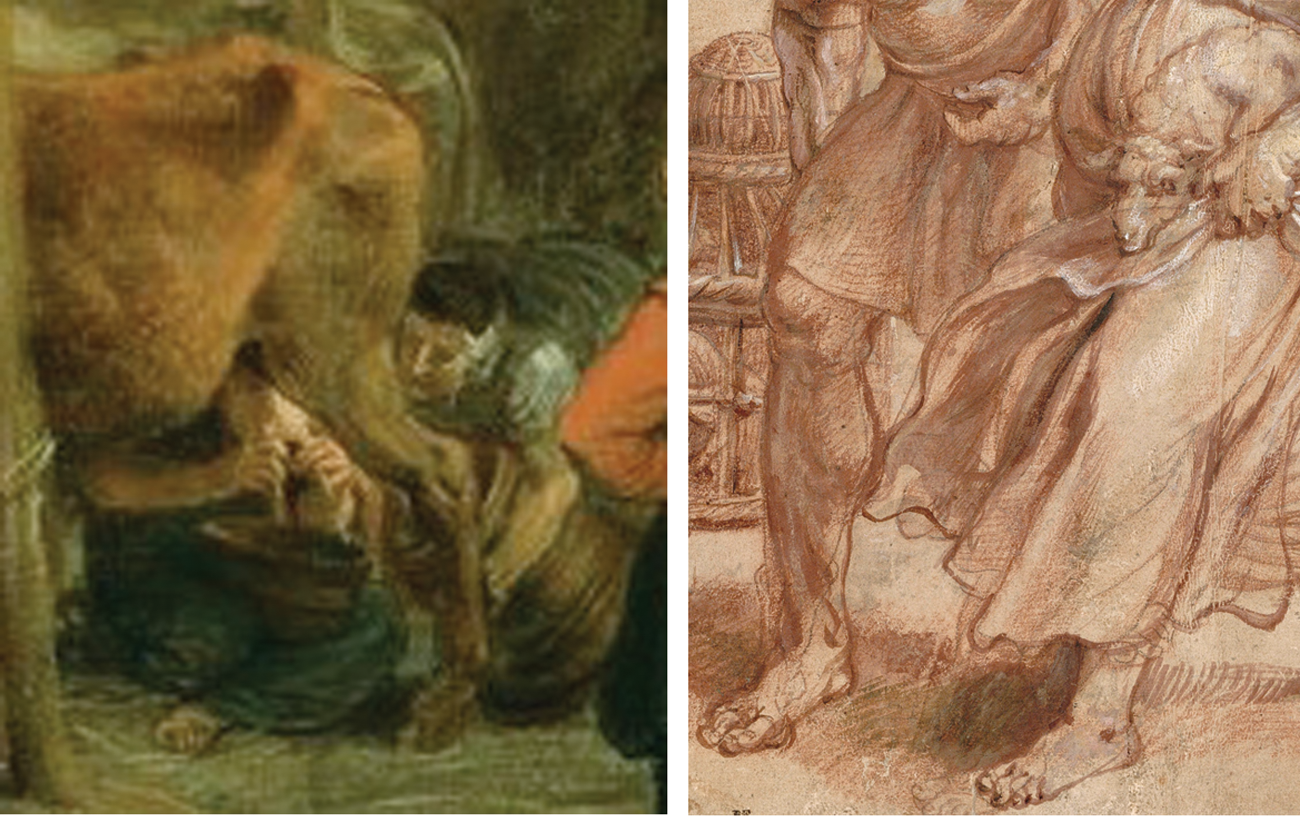

There are actually more intricate ties between art and thinking: our discovery of an artist’s inner logic and rhetorical strategies matters more than recognizing a biographical aspect in his works. Real life constitutes only one among the numerous referents that we can utilize in interpreting and even creating the effects of meaning and truth. Let us compare two pieces of work that attest to such a division between viewpoints in practicing art history: (1) one of Rubens’s landscapes, Winter: The Interior of a Barn (1618–19); (2) a late sixteenth-century drawing, An Old Peasant and Two Young Women on Their Way to Market, that Rubens retouched toward the end of his life (1635–40; Belkin Reference Belkin2009, 88). On the right of the winter landscape, a milkmaid is seen working and sitting cross-legged behind a cow (fig. 7).

Figure 7. Comparison and contrast between Rubens, Winter: The Interior of a Barn (left) and An Old Peasant and Two Young Women on Their Way to Market (right). Musée du Louvre. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

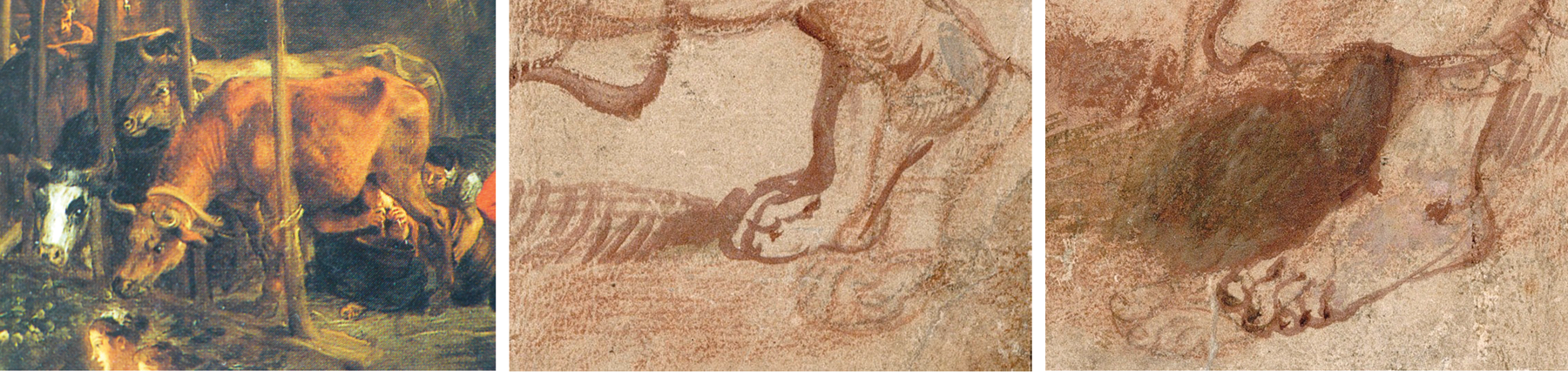

However, her face remains hidden behind the udder and teats of the animal and only her heavy bare hands and unshapely left foot are visible. Some comical effects can be seen even in the detail that exceptionally depicts in the face of the cow the emotions of anger and impatience (fig. 8).

Figure 8. Details showing the milkmaid working behind a cow and some intentional caricatures of foot. By permission of Royal Collection and Art Resource (representing RMN-Grand Palais).

In the retouched drawing, Rubens modified to a large extent the nose, hairdo, the jar, and the feet of the maid on the right. Likewise, her right foot is deprived of the refined distinctions between toes while her left foot is made like an animal’s claw (fig. 8). It has been asserted that Rubens owes his portraiture of female visages and hairstyles to Titian and other masters (Müller Reference Muller1982; Haverkamp-Begemann and Logan Reference Haverkamp-Begemann and Logan1988; Vergara Reference Vergara2002). However, the feature of being barefoot is more idiosyncratic: mythical or biblical female figures in his allegorical paintings also appear barefoot (Belkin Reference Belkin2009, 268). On the one hand, concerning the skills and styles of representing female heads, the image of a faceless milkmaid creates a certain uncertainty among viewers: Rubens temporarily annulled his relationships with other masters he had copied or imitated. On the other hand, he appears to have repeated the caricature of an unshapely bare foot to emphasize his own peculiar way of depicting milkmaids.

On our first encounter with these intentional caricatures, we may find them extremely unpleasant, or even rather ugly, and we may want to keep our distance from them. It may also appear a daunting task to appreciate some true thoughts behind them. However, we should regard them as a series of “clues,” “traces,” or “evidence” that we cannot avoid (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg, Tedeschi and Tedeschi[1986] 1992; Reference Ginzburg, Tedeschi and Tedeschi[2006] 2012). These details can be easily neglected or disparaged, yet putting them in order may lead us toward a revised reading of the iconographic viewpoint. Although these sketchy and minor details appearing at the margins of animal and human bodies may not correspond to any major style of painting accepted in art history, they vividly reveal the painter’s originality or unique artistic sensibility. They also enlarge on our demand for establishing a semiotic system that values imperfections as some kind of experimental or new evidence. Our task is: how should we change our attitude so as to avoid feeling silly or fooled? What can we do to feel emotionally encouraged and even to develop something intellectually stimulating? There is a good chance of gaining “clarity” and “vividness” of meaning and truth if we manage to tell impressive stories: the word evidence in Greek (enargeia, a notion used to judge epic poets’ and painters’ skills) and its Latin equivalent (evidentia in narratione, a principle that orators should apply) actually suggest such a prospect of an engaging inquiry (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg, Tedeschi and Tedeschi[2006] 2012, 10–12, 21–22).Footnote 3

In order to make the most out of the surface of artworks, certain hermeneutic philosophers have advised us to consider experiencing and interpreting the visual arts as a way of playing. When viewing in this context, we would appreciate games of make-believe, tension, and, above all, participation (Huizinga Reference Huizinga[1949] 1998; Gadamer Reference Gadamer, Weinsheimer and Marshall[1960] 1994). A quite radical line of thinking is to imagine an artwork as an event of being (Seinsvorgang), as if it were a human being charged with vigor and vitality, so that we can enter into dialogue with it and work on mutual benefits, well-being, and solidarity (Gadamer Reference Gadamer, Weinsheimer and Marshall[1960] 1994, 144, 151; Gadamer and Ricœur Reference Gadamer, Ricœur, Bruzina and Wilshire1982, 304). This healthy approach to communicating with artworks is based on appreciating play as a legitimate way of overcoming the gaps between beings. In the first place, artworks are actually competent or informative if some parts of them have already attracted our attention. We then start wondering about these attractive details with an eye toward discovering some kind of meaning or surprise. Eventually, recognizing certain affinities with them, we gradually develop an enlarged picture about the participants in the game. Considering the constant comings and goings staged between addressers and addressees, some new revelations are expected to appear in each communication, and the benefits are equated to the joy of winning a game.

With regard to Flemish and Dutch paintings, Hegel already revised the then-prevailing impression of their crudity and vulgarity. Applying the notion of “sublation,” the approach of negotiating between extreme oppositions, he developed the idea that these works can actually arouse our sympathy or move our soul when we observe more carefully their explicit details, bright colors, and diverse situations (Gombrich Reference Gombrich1984, 59–60). For Hegel, compared with Italian paintings, which immediately give the impression of sweet and divine beauty, Flemish and Dutch works, though ill formed, can still evoke feelings of divinity and piety as we contemplate their qualities of naivety, cheerfulness, and comicality. Hegel also attributed this digression from Italian art to the freedom and boldness of presentations among Germanic artists (Hegel Reference Hegel and Knox1975, 882–87). The Dutch scholar Johann Huizinga noticed something similar when searching for some manifestations of the spirit of play in art history. He observed that Baroque painters such as Rubens were not all that serious with their works; they always included an extensive amount of play elements even while expressing intense religious emotions (Huizinga Reference Huizinga[1949] 1998, 182).

Hegel and Huizinga’s mediations between Rubens and his tradition endorse the practicality of applying the play concept to our way of perceiving oddities: (1) they more or less reveal an artist’s playfulness in his own art; (2) they are examples of relaxation from the artist’s standard or regular work; (3) we should absolutely enjoy being tricked so as to be clever in the game of meaning seeking (Reference Huizinga[1949] 1998, 23). According to Hegel and Huizinga, part of our task is to revive the experience of certain profound emotions while simultaneously engaging with play elements.

Let us look into the two works by Rubens once again (fig. 9). On our second encounter with them, we have already changed our attitude, being more confident of our discerning eyes in discovering things that may induce our emotive and analytic potentials. Huizinga provides us with a starting point, which is to observe patterns of alternation, that is, the underlying rhythm or logic of play. Fortunately, we do spot some patterns shared between the two works: farm animals/humans; the old/the young; women/men; individuals/groups; at work/at rest; sitting/walking; holding/shouldering; basket/pitcher, and so on. Such alternations between figures, actions, and attributes give the impression that a diversity of things is made to coexist harmoniously on the same horizon. Harmony also comes about in the way that the peasants go together with their livestock in a distinctive yet seamless fashion, and it appears that they enjoy each other’s company so that one cannot dispense with the other. By glancing back and forth between these various patterns as sympathetic viewer-players, we may even feel inspired, invited to experience the divine pact between God, humans, and animals as told in the biblical story of Genesis. When immersing ourselves in this sacred order, we find holy yet highly meaningful messages emanating from these schematic details.

Figure 9. Two approaches Rubens adopted in creating similar patterns. By permission of Royal Collection and Art Resource (representing RMN-Grand Palais).

The trick that Rubens has played appears at rather marginal sections of the two pieces: the milkmaids with one or two unshapely feet are made to go together not only with animals but also with male peasants. Rubens alternates between two approaches in creating such a playful pattern: (1) in the winter landscape, he makes the old man’s right hand obscure, since the big thigh of the cow blocks our view of the way he actually works out with the maid; (2) in the retouched drawing he compulsively obliterates the man’s left foot and makes his thigh hidden in the maid’s drapery (Belkin Reference Belkin2009, 267; fig. 9). However alarmingly incompatible and perceptually challenging these patterns appear as opposed to the others, we in our overall viewing cannot ignore them; they actually are the only schemes that serve to unify the painting and the drawing on the same horizons of judging. On the condition that we have already regained some sense of divinity and holiness, we may wonder how we can possibly attain some even more cheerful states of inner glow (Schein), some unification of various forms of the beautiful, the sublime, and the absolute, after taking steps to overcome the gap between these unique patterns and the rest of the scenes.

Rubens appears to have introduced a contradictory worldview into his landscapes. His unique world of thinking, as revealed in his schematization and modification of patterns, calls for a more interpretive work than resting assured with the fact of his marrying a much younger woman. Can we simply identify Rubens as any of these old peasants accompanied by young girls? These old peasants do not appear revitalized or excited at all. How else might Rubens have projected himself into these playful works while experimenting with his thoughts? It has been suggested that we should temporarily put off any external facts while assessing what we see in paintings. Rather, we should always start formulating our questions on the basis of the features in the paintings and then seek to establish certain patterns or arrangements. Such a revised procedure helps to discover a lot more interesting conditions, possibilities, and problems.

In order to overcome our historical, emotional, and intellectual distance from the oddities Rubens has created as we try to penetrate his unique world of thinking, we should also adopt dialectical and hermeneutical ways of interpreting the works. We aim to reduce the opacity of these images by conceiving Rubens as an autonomous yet creative agent who is able to experiment with unique schematizations and arrangements while seeking to mediate diverse traditions and worldviews.

Oneself as Another: Moral Creativity Regained and Empowered

Specifically, Rubens’s selfhood (ipse-identity) growing in relation to his mise-en-scène of odd images should not be narrowly interpreted as a revelation of certain traits in his personality or unwisely related to particular events in his real life. Rather, we should explore how his selfhood and artistic sensibility interact with his social environments and the artistic stimuli of his colleagues. By way of blending his works with other painters’ creative outputs, we will discover—through a unifying yet dynamic system—some fashions of mediating worldviews and devising the rhetoric of promoting Christian belief. Such a scope of looking into Rubens is grounded in our association of similar-looking images and alignment of sequences that extend far beyond his time, area, and tradition. In the course of weaving narratives for these forms, associations, and sequences, we will refrain from referring to ready-made iconographic or stylistic labels such as “Renaissance” and “Baroque.” A more encompassing picture and genuine understanding of Rubens’s effect in history (Wirkungsgeschichte) will emerge as we constantly enrich our capacity for comparing, contrasting, describing, and explaining details (Gadamer and Ricœur Reference Gadamer, Ricœur, Bruzina and Wilshire1982, 310–11; Szondi Reference Szondi and Mendelsohn1986, 22; Ricœur Reference Ricœur1991, 77; Pächt Reference Pächt and Britt1999, 104).

The Kantian notion of “moral sublime” serves our purpose well in enabling us to widen our horizons so that we can consider Rubens’s works in the position of other painters (Kant Reference Kant, Guyer, Guyer and Matthews2000, 173–76). Within the kind of international community that we are establishing for Rubens, we will argue for his benefits out of our admiration for a certain law that he and other painters have contracted. We will be balancing between imagining and reasoning—between our observation of oddities and our duty of associating them with meaningful contexts—so as to advance the well-being of the community. We will be actively taking a course of action to bridge differences seemingly spotted between beautiful and ugly forms, as if we were following a command that addresses our profound sense of responsibility. Becoming such morally creative agents free from the charge of stylistic labels, we ought to discover certain laws or principles that enable us to imagine unpleasant features in the context of charming and sweet images, as if they both together already formed part of the evolving artistic world conceived as a community.

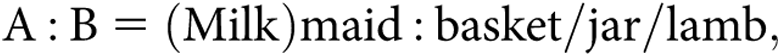

One of the laws (or psychological principles) that serves to achieve such ends is analogical reasoning. When operating within the formula (A:B = C:D) that juxtaposes two forms (A, C) and their derivations (B, D), we have no choice but to honor the fairly logical end product (D), however mistaken or absurd such a comparison may appear. Just as language learners make blunders while actually speaking, so artists may become weary of strict analysis while drafting and painting (Saussure Reference Saussure, Sanders and Pires2006, 107; Kant Reference Kant, Gregor and Timmermann2012, 38–39). The creation of bastardized forms—resembling not what is tutored but whatever one feels, desires, or imagines—is actually quite common in linguistic and artistic world makings. On the one hand, creative artists feel a confidence that they are actually beating a new path whenever they are attentively and prolifically working out their own designs. On the other hand, their imagination woven into their own works does not merely serve their selfish ends—their narcissism or idiosyncrasy—but their communities as a whole, where a lot more innovative ideas and patterns have been set against one another (Kant Reference Kant, Gregor and Timmermann2012, 45–47). Strange and deviant forms do not undermine the possibility that creative artists may be leading a dutiful communal life: they are able to reach out confidently and to associate their ideas with those of their colleagues. The power of analogical reasoning actually allows artists together with their peculiar designs to socialize and to travel beyond borders just like that of any standard and regular forms (Saussure Reference Saussure, Sanders and Pires2006).

Let us stage several encounters—meetings between similar-looking images—which enable us to empower the eloquence of (milk)maids painted and retouched by Rubens. We gather from the two pieces of work we have compared and unified (shown as fig. 9 and the central part of fig. 10) a formula

which enables us to associate Rubens’s designs with other painterly practices (A:B). The Virgin Mary has been recognized as one of the key figures (in the A position) that can be drawn into such a comparison and contrast (Shawe-Taylor and Scott Reference Shawe-Taylor and Scott2007, 136). This is fairly true, since Rubens has indeed inserted several images of a maid carrying a basket overhead into his depictions of biblical narratives—both standard and apocryphal—which appears to argue for the coexistence of Mary and the maid at crucial moments in biblical history (shown as the top row in fig. 10). The appearances of the maid in this context create an enlightening and cheerful atmosphere: she witnessed the scene of the first meeting between Christ and St. John the Baptist, who were not yet born (on the right); she was among those amazed to find that Christ together with his disciples forgave a sinful woman, Mary Magdalene (on the left).

Figure 10. A galaxy of images associating (milk)maids with the Virgin Mary, Venus, and Pax. Top left, Feast in the House of Simon the Pharisee (Rubens, 1618–20; the State Hermitage, St. Petersburg, HIP / Art Resource, NY); top right, the inner left panel of The Descent from the Cross (Rubens, 1611–14; Antwerp Cathedral, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY). Middle far left, The Divine Shepherdess (Miguel Cabrera, Mexico, 1760; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Digital Image © Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY); middle far right, The Annunciation to Mary (Basilica of San Marco, Venice, twelfth century; Scala / Art Resource, NY). Bottom left, Allegory of the Temptations of the Youth (Otto van Veen, 1595. By permission of the National Museum, Stockholm); bottom right, The Allegory of Peace (Rubens, 1629–30; © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY).

With the somewhat cumbersome looking jar—found not only in the late sixteenth-century Netherlandish drawing Rubens retouched but also in the medieval Greco-Roman tradition of depicting the scene of the Annunciation—Rubens argues that Mary and the maid shared the same blessed fortune of giving birth to the holy infant—“The message of the Nativity is conveyed without depicting Bethlehem” (Shawe-Taylor and Scott Reference Shawe-Taylor and Scott2007, 136). Among the Byzantine depictions that favored the Apocrypha, Mary was thought to have heard the angel’s whispers outside her house before the angel actually appeared to her indoors. She was portrayed in the act of drawing water with a pitcher so as to fulfill her task of spinning (the purple and the scarlet) assigned by the priest (shown on the far right in the middle row; Elliott Reference Elliott[1996] 2008, 37–38; Zuffi Reference Zuffi and Hartmann[2002] 2003, 55), just as the maids in Rubens’s landscapes appear to be preparing for farm work. Intriguingly, certain Italian painters such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Francesco Raibolini (1447–1517) also endorsed this tradition of depicting an open-air Annunciation. The whole episode—Mary hearing the news while reading the Holy Scriptures—was shown to have taken place outside Mary’s house. In addition to the courtyard where the angel and Mary communicated with each other, these painters created pleasant-looking perspectival landscapes as the background (with variations of trees, lakes, mountains, and the clear sky).

The lamb appears like an unusual attribute of Mary: it was frequently associated with Christ and certain saints or apostles such as St. Agnes and St. John the Baptist. By adding in his retouched drawing a grotesque-looking image of the lamb on the maid’s skirt (Belkin Reference Belkin2009, 267), Rubens endowed Mary with certain unexpected qualities—she was not just passively reading or receiving the divine light but actively reaching out and working together with folks, just as any apostle figure might behave. In addition, Rubens actually thickens the bare hands of the maid holding the lamb, making her nose appear masculine and her feet beast-like; all these revisions suggest that he may have thought about transforming the maid into a male figure. This said, the old peasant whose left foot Rubens hides in the maid’s drapery can be reinterpreted as a collaborator rather than a lusty old man. Stunningly, Rubens’s approach to representing Mary serves to bridge medieval legends that describe Mary as “the good shepherd” who governs the church with the blessed fruit of her womb (Sainte Antoine, 1389–1459) and eighteenth-century Spanish appendages of the lamb to Mary as a shepherdess. Images of Mary presiding over and touching lambs were actually quite popular in Spain and Spanish America (shown in fig. 10 on the far left in the middle row; Stratton-Pruitt et al. Reference Stratton-Pruitt2006, 172–75).

The remaining intriguing detail to engage with is the milkmaid whose face is masked by the udder and teats of a cow. How can this be associated with any divine message and be integrated into the same formula of analogical reasoning? The image of milking reminds us of an allegory that Rubens’s master Otto van Veen painted and that he much later tactfully revised (shown as the bottom row). Compared with his Flemish master’s design, which emphasized the antagonism between Venus and Minerva (on the left), Rubens’s composition (on the right) induces us to reflect upon their hidden harmony by evoking the alliance between Pax and Minerva, both of whom actually govern civil virtues in their own ways (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal, Baskins and Rosenthal2007). The image of Minerva’s bare right hand is given a new function concerning action taking: rather than simply deflecting the milk which Venus draws on to seduce a young man, her right hand defends Pax from the intrusion of Mars and the Furies.

Rubens’s blending of looks and attributes renders Pax a Venus-like figure: the winged putto holding an olive wreath and a caduceus is a symbol of Pax, while around her the leopard and the satyr, although friendly and peaceful looking, cannot be dissociated from the frenzy of lusts that Venus evokes. Rubens’s modifications transform Venus into a guardian of maternity who works closely with Minerva in upholding a nation. Such a conceptual detour was actually preceded by the Italian convention of depicting victorious Venus (Venus Victrix): artists fused Venus’s naked body with Minerva’s gear as one unity so as to express emperors’ longings for peace and to glorify their prospects for the future (Wittkower Reference Wittkower1977). The same logic can be applied to observing and interpreting the significance of down-to-earth (milk)maids in Rubens. They actually appear quite original and powerful in engaging, bridging, and unifying diverse traditions of storytelling and image making. Just as Venus and Minerva work together in safeguarding national peace and prosperity, the milkmaids and the old peasants, that is, Mary and the apostles, cooperate seamlessly in preaching the Christian faith.

Rubens’s selfhood (ipse-identity) regains its vitality through our associating attributes he employs with similar-looking images found in certain depictions of Mary and goddesses. The galaxy of images (shown in fig. 10) gathered and grouped together from inside out renders prominent Rubens’s profession as a painter. His profound connections with treasures of tradition go beyond the strictures of his real life. The networking enables us to perceive subtle interconnections between images and narratives while appreciating the permanence of Rubens’s image making across times and geographical areas by way of vibrant analogical reasoning. Such a global perspective serves to revise the crude interpretation that identified Rubens as any of the old peasants accompanying youthful-looking maids, and so we are advised not to confuse such a thing [idem-]identity with selfhood. The global perspective rather gives rise to a new look at Rubens, together with the oddities he created; his new identity is now recognized as the outcome of our schematic yet delightful play on storytelling. As semiotic cum hermeneutic players, we have not only broadened our horizons of judging and interpreting but also fulfilled our duty of creating a surplus of meaning.