While briefly working in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with the faculty of an intercultural bilingual education master’s program, one of the faculty members related to me an interaction he had had that illustrated the complex valences of class, gender, and race that the term bilingual carries in Bolivia. In his search for a residence in Cochabamba he had been shown properties around middle-class neighborhoods on the northern perimeter of the city. While touring these homes there would come a moment when the real estate agent would point to a room that has been, and continues often to be, used as a maid’s quarters. This room she referred to as el cuarto para la bilingüe—the room for the bilingual (woman).

Bolivia is a multiethnic, multilingual society, even officially so, with thirty-seven languages afforded official status since the passing of the 2009 constitution. Most of these thirty-seven languages are spoken in the linguistically diverse Amazonian north of the country. In the Andean highlands of the country’s west, Quechua and Aymara are spoken in addition to Spanish by millions of people, particularly in rural areas, but also in cities like Cochabamba and La Paz. In urban contexts like La Paz, El Alto, Cochabamba, Sucre, and Oruro, Quechua and Aymara are spoken and can be heard in markets, on the radio, and in neighborhoods populated by migrants from the countryside. Even in the wealthiest, whitest neighborhoods, however, as the agent reminds us, it is quite likely that in the kitchens where food is cooked and the patios where laundry is tended, the help will be bilingüe.

In the Bolivian context, speaking Quechua, Aymara, or another Amerindian language is both racialized and racializing. It is also more than that. The real estate agent’s remark projects an image of a gendered subject. The agent’s metonymic reduction of the domestic worker to her linguistic practice ties together an overdetermined knot of gender, class, race, space, and language. Bilingüe used as such betrays class, gender, and ethnic tensions that my colleagues in the Bolivian university might prefer be washed out in more technocratic projects like their own, namely, the professionalization of teachers working within the rubric of intercultural bilingual education.

The presence of indigenous women in the homes of wealthy white families as maids, not just simply conducting occasional labor but often also residing in the homes of their employers, referred to as working cama adentro ‘bed inside’, persists in Bolivia and throughout the region. By some recent estimates, domestic workers make up as much as 15 percent of the working female population in Latin America (Reference BlofieldBlofield 2009). The isolation and dependence of domestic workers on their employers have made these women particularly vulnerable to abuses, particularly those who work cama adentro. This labor exists within a racially stratified division of labor such that domestic workers are overwhelmingly indigenous women in Bolivia. A 1995 survey of domestic workers in La Paz found that 85 percent of live-in (cama adentro) domestic workers and 75 percent of non-live-in domestic workers were Aymara (Reference BlofieldBlofield 2012). The same survey found that 85 percent of workers between the ages of 18 and 25 worked as many as 80 hours a week, some only receiving as little as three hours of sleep a night, and that other abuses—including lack of access to health care and psychological and sexual assault—were widespread (Reference BlofieldBlofield 2012, 84).

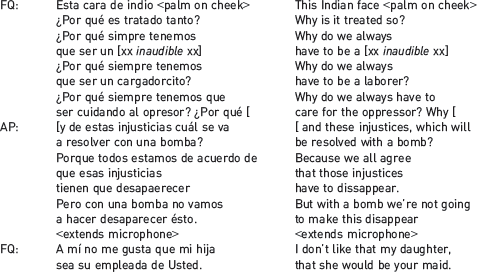

The indexical associations projected from a real estate agent’s pointing to a small room adjacent to the kitchen, denoting it as the room for la bilingüe are likely to be as asymmetrical as the society in which the person listening is situated. Does the figure of the domestic worker evoke notions of mother-like care from an intimate Other, or does this figure index histories of racist humiliation, sexual vulnerability and abuse? The stark gap between the violence implicit in the situation of the domestic worker was laid out dramatically in a mediatized moment of confrontation between Aymaras and white Bolivians in the wake of a moment of dramatic political violence and heightened racial tensions in Bolivia following the 1992 Tupak Katari Guerilla Army (Ejército Guerrillero Tupak Katari, or EGTK) attack on a La Paz electrical plant. During the trial of a prominent member of the EGTK’s leadership (fig. 1), Felipe Quispe (FQ), he explained his motivation following his arrest in antiracist terms, but when he was interrupted by a white woman journalist, Amalia Pando (AP), his motivation for the attack shifted the terms of antiracism from talking about himself and his skin to speaking of his daughter and his wish that she never be a maid:Footnote 1

The journalist’s line of questioning situated Quispe squarely as the perpetrator and advocate of violence in this scenario. Quispe fulfilled the image of a crazy-eyed bomb thrower well. The rage in his eyes at the journalist is visible. For his actions are ones that entail violence for the journalist, while his list of complaints concern acts of injustice, not violence per se; after all, “Todos estamos de acuerdo que esas injusticias tienen que desaparecer [Everyone agrees that those injustices have to disappear].” His response that he does not want his daughter to be her domestic worker underscores that such a fate for his daughter, for him, was a situation already permeated with violence.

Figure 1. Felipe Quispe addresses Amalia Pando in a televised interview following the August 19, 1992, arrest.

Ten years later, Felipe Quispe would make an unsuccessful bid for the Bolivian presidency. The political trajectory of his then EGTK comrade Álvaro García Linera has been more successful. García Linera has been Bolivia’s vice president since 2006. Quispe’s response to Amalia Pando, however, has become famous in Bolivia, having resonated with many indigenous Bolivians’ sense of indignation and anger at the indignities and humiliations they face.

While progress has been made in terms of legal protections for domestic workers, the abuses documented during the 1990s remain very much a part of the Andean present. As recently as September of 2017, an Aymara woman came to the Vice Ministry of Justice demanding back pay for 36 years of unremunerated work for a family in La Paz’s wealthy southern zone. Essentially having lived in conditions of captive servitude, Tomasa Machaca had been working for a wealthy white family without pay for 36 years. As a child the family had told her they had saved her as an orphan, deceiving her to believe that her family was dead.

While a potent figure of the inequalities of Bolivian society, the figure of the domestic worker is neither the beginning nor the end of how race relations, gender, familial intimacy, sexuality, and linguistic difference come together in Bolivia. The association of indigeneity with women and, more specifically, with vulnerable women sexually available to white men reaches back to inaugural moments of European invasion of the continent. The trope of the indigenous maid as at once a nurturer and a figure of sexual initiation for white men is a long-standing trope that Marcia Stephenson (Reference Stephenson1999) has documented as recurrent in Bolivian literature. As a discursive figure, it is one with a long history; but “Indian maids” are also biographic individuals like Tomasa Machaca, who live within structures inherited from colonialism, passed on through the Republican era to the current day. When the well-heeled real estate agent points to a cramped room with a bed, adjacent to the kitchen and patio, and says “this is for the bilingüe,” it is a vivid and telling conflation of language, race, gender, and history.

Linguistic anthropologists have developed many ways of analytically describing the agent’s metonymic move. The projection of an image of la bilingüe as an indigenous maid is an example of rhematization (Gal and Reference GalIrvine 1995; Irvine and Reference IrvineGal 2000)—tying linguistic practice to an image of speaker, and here a markedly raced and gendered one. The longer histories that make such rhematization possible, that allow for an array of signs across different modalities—features of language (bilingualism), particularly embodied speakers (Indian women), distinctive modes of action and behavior (cooking and cleaning), sartorial styles (Indian dress)—to cohere into an emblematic figure of personhood are examples of processes of enregisterment, which yield enregistered emblems that are widely known to a social domain of persons (Reference AghaAgha 2007). That otherwise disparate signs seem to belong together within one emblematic category is a kind of metasemiotic regimentation that establishes cross-modal iconism relying on congruent indexicality (Reference AghaAgha 2007, 22), a situation in which kinesic, embodied, verbalized, sartorial signs all point to a shared image of predicable regularity for those in the social domain of the emblem. Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores call for attending to the enregisterment of race and language in particular, seeking, “to understand how and why these categories have been co-naturalized, and to imagine their denaturalization as part of a broader structural project of contesting white supremacy” (Reference Rosa2017, 1). H. Samy Alim, in the introduction to the volume Raciolinguistics insists that such a project be comparative and intersectional, acknowledging that race is, “always produced in conjunction with class, gender, sexuality, religion, (trans)national, and other axes of differentiation” (Alim et al. Reference Alim2016, 6). These calls for raciolinguistic approaches ask to attend to particular fractions within processes of enregisterment, the racial and the linguistic, asking how and to what ends such a co-naturalization of bodies and linguistic practice have come about in the first place. In recognizing that linguistic practice, whether a discrete feature or an entire linguistic code, may index a body, and a racialized one, it follows that this racialized body may also be gendered through similarly historically contingent processes.

Casta Paintings as Metasemiotic Regimentation of Race and Gender

Axes of difference such as race, class, gender, sexuality, and religion are not prediscursive, but are themselves the product of historical processes of metasemiotic regimentation and grouping. Race and gender in the Americas, for example, have been tied up closely with one another since their inaugural constructions in the course of colonialism. This is most clearly illustrated through the sistema de castas, the elaborately articulated racial and gender order operative throughout the Andes and Spanish colonial America. Paintings were created to illustrate the human diversity of the colonial new world. These paintings were diagrams of man, woman, and offspring that functioned to both explain and establish the colonial order, including the ordering of race, language, gender, and privilege. The caste system organized colonial subjecthood: who would pay what kinds of taxes to whom, who could be enslaved or free, and even who could be tried as a witch. Casta paintings were hierarchically organized grid diagrams. In each square could be found images of a man, a woman, and a child. Many have noted that these images give as much, if not more, attention to sartorial detail than they do to phenotype. Each grid has an accompanying label designating racial status to each within a procreative equation: “A Spaniard, an Indian woman, a Mestizo.” These paintings were less a description of an already existing state of colonial affairs than they were sketches of a state of affairs that colonial social engineering projects sought to create.Footnote 2

Figure 2. Anon., Mestizo con Yndia producen Cholo (1770), from the Peruvian casta paintings of Viceroy Manuel Amat y Juniet. Reproduced with the permission of the National Museum of Anthropology (Madrid, Spain).

While few of these labels remain today, some of them do. Mestizo, for example, still denotes mixed heritage throughout the Americas (if with less specificity than in the seventeenth century) and sambo is still used (nonpejoratively) in Bolivia to refer to people of mixed African and Indigenous descent. The Bolivian chola, the urban Indian woman, demonstrates not only a racial category remaining from colonialism, but in her skirt, petticoats, shawl, gold jewelry, and hat, we see reverberations of Spanish colonial style. The entire ensemble is referred to as a pollera. If not already established or if at all in question, one way to establish one’s status as an “authentic” Indian is to point out that one’s mother wore a pollera.

Denigration of the Indian Other

The legacy of the racial hierarchy displayed in the casta paintings and the overarching logic of white supremacy remain alive in the widespread veneration of the European phenotype today, and in the relegation of non-Europeans to abject status in the public sphere across societies in the Americas. Images of white women abound in advertising and public spaces throughout Bolivia. Beauty queens from the east of the country, known as las magníficas, are famous nationally and appear in commercial promotions of diverse kinds. That these women are from the east of the country is important. As elsewhere in the world, regional provenance is the source of robust and capacious stereotypes that include set construals of race and gender alongside notions of demeanor, mental disposition, work habits, and political affiliation. Anna Babel, for example, discusses her Quechua-speaking informants’ stereotypes of Bolivian highlanders as hardworking but brusque and argumentative, whereas lowlanders are perceived as lazy but jovial (Reference BabelBabel 2014, Reference Babel2018). The figure of the “beautiful cruceña” is one that is promoted through figures like las magníficas and contributes to the racializing of region in Bolivia, with the highland west being associated with Amerindian bodies and the lowland east with European ones. The robust cross-modality of these stereotypes as grouping together diacritics of gender, racial phenotype, and language use was evidenced in the comments made by a beauty queen from the east of the country in 2004 at a Miss Universe competition in 2004. The aspiring Gabriela Oviedo unashamedly expressed her contempt for her conational Others when she stated before a panel of Miss Universe judges that,

unfortunately, people that don’t know Bolivia very much think that we are all just Indian people from the west side of the country: it’s La Paz all the image that we reflect is that poor people and very short people and Indian people. … I’m from the other side of the country, the east side and it’s not cold, it’s very hot and we are tall and we are white people and we know English so all that misconception that Bolivia is only an ‘Andean’ country, it’s wrong, Bolivia has a lot to offer and that’s my job as an ambassador of my country to let people know how much diversity we have.

(Reference CanessaCanessa 2008, 56; Reference NavarroNavarro 2012).Anthropologist Bret Gustafson has argued that eastern Bolivian elites have doubled down on gendered racializing discourses precisely because of resurgent indigenous power in the country, stating that, “Facing the erosion of racial privilege and traditional social boundaries, regional elites use spectacle to visualize ‘power’ through displays that naturalize gendered, racial, social, and spatial boundaries and conjure grandiose illusions of prosperity against the underlying precariousness of both” (Reference GustafsonGustafson 2006, 353).

Other mediatized moments of Indians’ relegation to an abject position come through comedy. Elsewhere, I have examined a Bolivian television show in which white actors portray, among other national stereotypes, Aymara men as hyperviolent, irrational, but also pathetic, weak, emasculated, or even barely male. These performers replicate the vowel alternations stereotypically associated with Quechua or Aymara bilingualism as part of their performance of a vulgar, contemptible, racial, and gender Other (Reference SwinehartSwinehart 2012a). In neighboring Peru there is a similar figure who crosses both racial and gender lines, with La Paisana Juancinta.

Public ridicule of Aymara- and Quechua-dominant speakers’ pronunciation of Spanish became particularly prominent in the wake of the election of Evo Morales in 2006. An example of this can be seen in an editorial cartoon, “Spanish according to Evo” which appeared in the newspaper El Mundo on June 14, 2011 (fig. 3). In the cartoon, Morales pronounces words such as señor and recuperando with an i instead an e and confuses the word lúcido with lució, which serves to deliver the punchline for the cartoon’s joke. The cartoon was published to accompany a brief announcement of the publishing of a book by the journalist and poet Alfredo Rodríguez, president of the Asociación Cruceña de Escritores (Santa Cruz Writer’s Association). The book’s title, “Evadas” cien frases de Juan Evo Morales Ayma para la historia (“Evadas” one hundred phrases of Juan Evo Morales Ayma for history), turns the president’s name into a pun. Evo becomes “Evadas,” which sounds like a past participle (suggesting things he’s said) but, more prominently, and poetically, suggests through rhyme the Spanish word for nonsense—huevadas—furthering the notion that bilingual Spanish is not only ill formed but also illogical and, literally, nonsensical.

Figure 3. El Mundo cartoon by Alfred Pong, June 14, 2011. Reprinted with the artist’s permission.

Cholas Taking Charge

Such Other-centric voicings of Indians by whites, however, are just that: Other-centric. They are made by whites for whites, if intended for Indians they are intended to be overheard and perhaps provoke humiliation or shame. Such depictions are anchored ultimately to a set of norms and values at odds with the world of indigenous Andeans, a state of affairs about which many of them have no confusion. Here, we should pause to make note of a historical homophony that rings across the hemisphere and listen to how colonialism echoes differently across the Americas. Chola in the United States evokes a different figure of personhood, albeit one who is similarly enregistered in terms of race, gender, and language—a Mexican American gang-affiliated woman. Norma Mendoza-Denton’s ethnographic description of Californian cholas’ orientation to otherwise dominant norms of femininity in the United States could just as well describe these Bolivian cholas, even more southern than Mendoza-Denton’s sureñas, their tocayas of the Andes: “cholas (and many other subaltern groups with their own aesthetic norms) are not only not outside of the “female aesthetic community” but want no part of it, actively rebuffing and contradicting it (Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008, 160).”

Cholas of La Paz have their own beauty pageants such as Miss Cholita Ñusta La Paz and Miss Cholita Ñusta of the Public University of El Alto. Beauty pageants of Indigenous women conducted in formats analogous to Miss Universe, but in the name of indigenous cultural life occur throughout the Americas, among Maya in Guatemala (Reference ShaktShakt 2005) and Amazonian Kichwa (Reference WroblewskiWroblewski 2014). Like in Mayan and Napo Kichwa beauty pageants, Chola beauty contests similarly demand indigenous language fluency as an explicit requirement—the stipulations from 2014 Miss Cholita La Paz state: “The participants must be legitimate and authentic Cholitas representative of the social group of Chola tradition. Candidates who disguise themselves as cholita will not be accepted, nor who do not wear original braids and only show up dressed in pollera for the contest. Participating cholitas, in addition to Spanish, must speak a native language (Aymara or Quechua). In addition, they must be presented with the typical attire of Chola La Paz and its characteristic ornaments.”

In Amazonian Kichwa beauty contests, contestants address Kichwa judges and audiences with what Michael Wroblewski (Reference Wroblewski2014) calls an “intercultural code” that is neither local Napo Kichwa nor the panethnic Unified Kichwa, but draws on both. Cholitas, on the other hand, demonstrate eloquence through their command of a dehispanicized variety of Aymara that, while emerging from processes tied to bilingual education that are similar to Kichwa Unificado, is understood locally simply as being “pure Aymara.”Footnote 3 Aymara women generally have a reputation among Aymara bilinguals as being hypervigiliant of linguistic form, as “guardians of the language.” Here we could note some similarities with and divergences from the situation attested to by Jane Hill (Reference Hill1987) among Mexican speakers of Nahuatl. In this case, where Nahuatl was the language of male-dominated local politics and the interface with broader Mexican society was in Spanish, women were more likely to adopt hispanicized forms, while men were more invested in “pure,” that is, dehispanicized, forms of Nahuatl. Aymara women are well integrated into the Bolivian economy, with many cholas being successful and even quite wealthy business women.

If Bolivians are to claim Indian heritage, it is far more common to hear people speak of their mother in a pollera rather than a father in a poncho or wearing sandals. Why might this be? After all, while the notion of a “mother language” is, of course, widespread, that the language that is most “naturally” one’s own as the result of intergenerational transmission be a “mother language” is not universal. In the northwest Amazon, for example, the combined practices of linguistic exogamy and patrilocal residence have meant that, traditionally, it has been one’s father’s language that is one’s “own” (Reference FlemingFlemming 2016). The interface with the broader Bolivian society, in particular the state itself, helps explain how the figure of the mother in pollera and being an Aymara speaker have come to presuppose each other.

Obligatory military service for males has been a right of passage for Bolivian men, particularly rural Indian men (middle-class and wealthy Bolivians often pay out of it). In her ethnography of life in the altiplano and El Alto, Lesley Gill has noted that “military service is one of the most important prerequisites for the development of successful subaltern manhood, because it signifies rights to power and citizenship” (Reference Gill1997, 527). For rural Indian men it has also meant entrance into a Spanish-speaking world. Andrew Canessa writes of this process, noting that historically it has been the case that the military has been a place where young men learn “that speaking Aymara is punishable and that, in this racially hierarchical army, indian men can not expect to be officers unless, that is, they ‘progress’ and change their name from ‘Condori to Cortés’” (2008, 51). In fact, many Aymara families have hispanicized names precisely from such processes: for example, Mamani became Halcón, and Panqara Flores, which mean “falcon” and “flowers,” respectively. Another common Aymara name, Quispe, receives a b and a silent –rt to give it a French-looking orthography: Quisbert. To admit that one’s father was monolingual would be to place him outside not only the realm of citizenship but also outside of a key site in the regimentation of Bolivian masculinity.

What remains unclear, though an ethnographically answerable question, is the extent to which new policies within the armed forces during the past decade pose to change this gender-race-language dynamic. Functionally, Spanish remains dominant throughout Bolivian social and political life, yet it is not the case in 2018 that Bolivia is only imagined by its citizens as primarily a monolingual nation. With regards to upward mobility, I have in my research among Aymara radio broadcasters found that the model speaker of “dehispanicized Aymara” being a pollera-wearing woman has made broadcast media a corner of the Bolivian labor market where Aymara and Quechua women have upward mobility not found elsewhere (Reference SwinehartSwinehart 2012b). Roxana Mallea, for example, is a news reporter for Bolivia TV who wears a pollera both in studio and when reporting out in the field, including when she is reporting from abroad, whether in Washington, Brussels, Paris, or Buenos Aires.

In an interview for her own news channel, in a “meet our reporters” segment, she spoke to her background and career. She is from El Alto and is the daughter of migrants from the Pacajes province south of Lake Titicaca. While studying to be a nurse she was recruited to participate in a casting and, upon securing a position as a news broadcaster, shifted her course of study to journalism and social communication. In her interview she reanimates the voice of her monolingual Aymara-speaking mother for the listening audience, both acknowledging her mother’s guidance in securing her own professional success and also possibly counseling other viewers with this maternal Aymara wisdom:Footnote 4

Conclusion

In this article I have laid out broad outlines of figures of personhood that, in moments, map onto biographic individuals like Tomasa Machaca, or a well-known news broadcaster like Roxanna Mallea. Figures of personhood are emblematic models of stereotypic social kinds to which people may orient, that they may reject, or that may simply become topics of commentary and debate. They are discursive figures and not biographic people. They group together a number of features of perceivable behavior, including race, language use, work habits, occupation, gender, and others, and unify within apparently discrete categories of social personhood. Once they come into sociocentrically widespread existence, people negotiate footings with them, and with other people through them, in the course of social interactions. Aymara women are, of course, neither only abused maids nor always wealthy cholas. They are also professional women, poor women, rockers, churchgoers. There are Aymara women who wear Western dress and consider themselves Aymara nationalists, and cholas who are more eloquent in Spanish than Aymara. This brief study shows that the question of how gender is structured in Bolivian society cannot be separated from questions of how ongoing processes of Aymara’s enregisterment unfold, and how competing models come to co-exist with each other for distinct social domains of people in a society marked by wide-scale multilingualism and a resurgence of indigenous political power.