Scholars have long argued that business corporations rely on strong reflexive metacultural discursive processes to produce and reproduce (and often modify) a cultural framework that will align with the corporation’s business goals and with which corporate members will be able to identify. This line of research has focused particularly on the role played by rituals, narratives, myths, and slogans in corporate efforts to reflexively solidify (and modify) specific corporate cultures according to shifting conditions (see Urban and Koh [Reference Urban and Koh2013, 150–51] for bibliography).

In this essay I examine such corporate discursive processes by taking up a genred corporate event that has received little attention within this line of research, namely, the “workshop,” a short learning event organized by a consultancy group to representatives of vastly different corporations. The workshop presents a unique opportunity to study corporate reflexive metacultural processes because it revolves around the attempt of an organization (the consultancy group) to convince members of vastly different corporate cultures in a relatively short time frame that its services can add value to their corporations, which would justify a long-term consulting relationship. As opposed to “in-house” corporate rituals and events, then, on which most studies have focused and which involve members who are routinely exposed to the corporate culture that is the focus of such rituals and events, the workshop facilitators need to quickly and efficiently recruit the participants into a specific corporate culture to which they have not been exposed before. In such a context, reflexive metacultural discursive processes play an even more important role than is usually the case.Footnote 1

Furthermore, the services provided by the consultancy group that is featured in this essay are suffused with an inherent cultural contradiction that results in heightened reflexive metacultural work in an attempt to resolve it. As opposed to consultancy groups that provide “hard-core” technologies that appear, at least on the surface (though never in practice), to be relatively independent of cultural dimensions, I focus on an innovation consultancy group in whose workshops participants are supposed to learn a set of innovation techniques for generating new products and services.Footnote 2 Set within a specifically Western modern normative framework, the task of such a consultancy group—to build and foster a stable corporate culture of innovation—embodies a basic cultural contradiction because, as I will show in detail, innovation is widely associated with notions that derive from a modern Romantic ethos of creativity, which itself connotes unpredictability and resistance to formalization and routinization (Wilf Reference Wilf2013b). The promise of consultancy groups to help corporations to build a culture of innovation that will be productive of a stable pipeline of ideas for new products and services is thus the promise to routinize that which ideologically cannot be routinized and whose value is precisely in its resistance to routinization. Against this backdrop, this innovation workshop offers a privileged viewpoint from which to theorize reflexive metacultural processes because the workshop facilitators’ task is first and foremost to reframe this cultural contradiction and thus to allow the participants to inhabit the—on the surface, counterintuitive—idea that innovation can and should be routinized, formalized, and rationalized. Their task, in other words, is to inculcate certain valorized capacities in the participants (innovation, creativity) by means of forms of reflexivity that foreground, stereotype, and, crucially, invert features of the participants’ current institutional and cultural landscape.

I suggest that existing lines of research in organization studies, which have focused mostly on the denotational texts of rituals, narratives, myths, and slogans as the building blocks of corporate reflexive metacultural processes, are limited in their ability to account for such reframing. To make sense of the interactional force of this innovation workshop, in particular, and of other ritualized corporate events, in general, it is necessary to draw on theoretical advances made in the past three decades in the fields of linguistic anthropology, discourse studies, and sociolinguistics, which have elaborated on the ways in which the production in real-time communicative events of denotational coherence becomes the basis for the production of interactional coherence, that is, “the ways that individuals of various social characteristics are ‘recruited’ to role-relations in various institutionalized ways, and consequentially, through semiotic behavior, reinforce, contend with, and transform their actual and potential inhabitance of such roles” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein and Sawyer1998, 268). I argue that the workshop facilitators, by engaging their listeners in different discursive processes in different sessions throughout the workshop, reflexively bring into being a specific macrosociological order that opposes a Romantic ethos and a professional ethos. This macrosociological order then becomes the basis for the microsociological context of role-inhabitance during the workshop and for suggested transformations in the workshop participants’ role-inhabitance within this context and with respect to innovation, namely, from their role-inhabitance of a Romantic ethos at the beginning of the workshop to their entailed role-inhabitance of a professional ethos at the end of the workshop, where the professional ethos aligns with the system of innovation developed by the consultancy group. I suggest that at stake is business corporate ritual semiosis, namely, a business corporate ritual event that dynamically figurates the concrete effects it is meant to have in the corporate world and that is meant to have such effects precisely by virtue of such figuration.Footnote 3 Such events, it should be emphasized, constitute a key dimension of any business corporation’s cultural logic. They can find expression in employee training events, strategic planning meetings, homecoming receptions for previous employees, presentations for current and potential investors, public relations initiatives, and more. Their semiotically informed analysis is thus an important condition of possibility for understanding the social life of contemporary business corporations.

Setting Up and Walking Across a Macrosociological Poetic Landscape

Immediately at the beginning of the very first session on the first day of the workshop, Alice, one of the four facilitators, a woman in her early forties, addressed the participants:

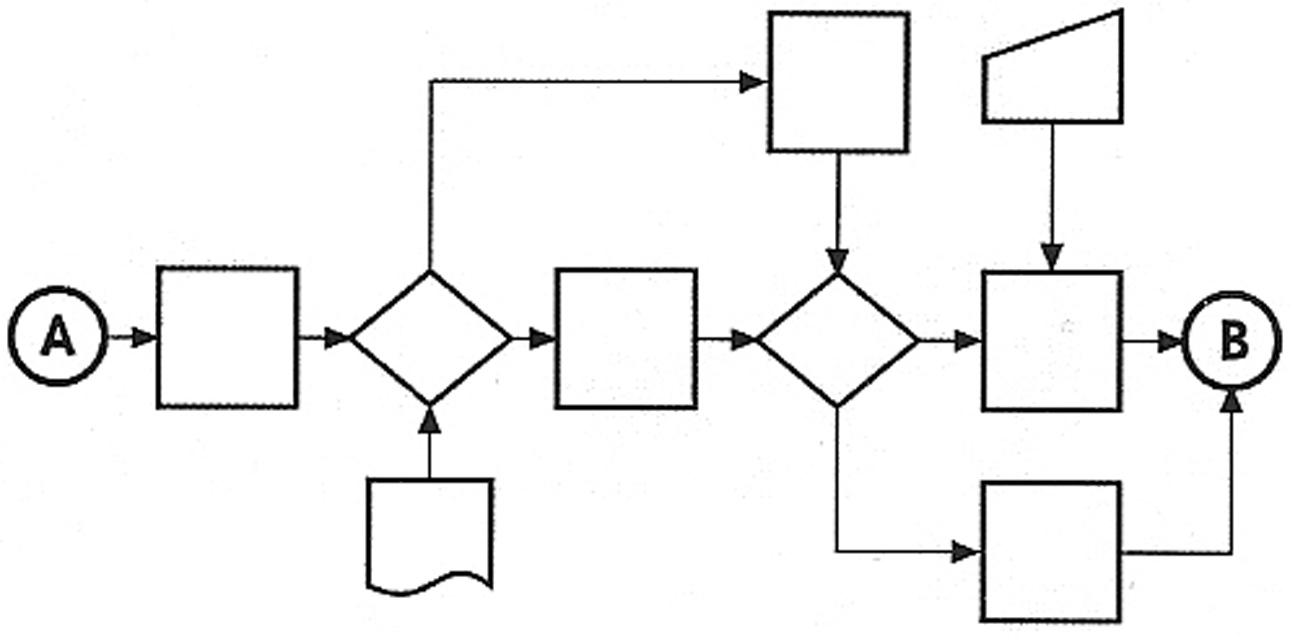

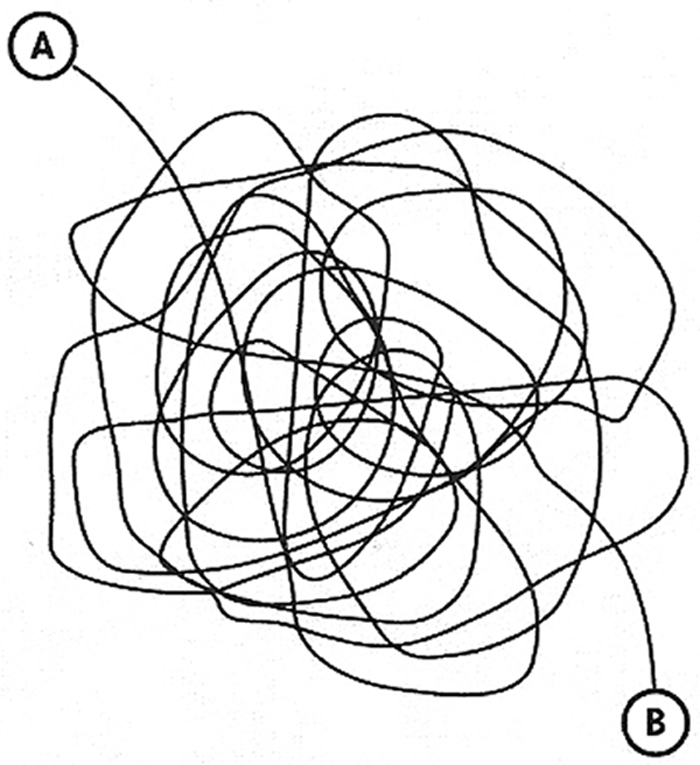

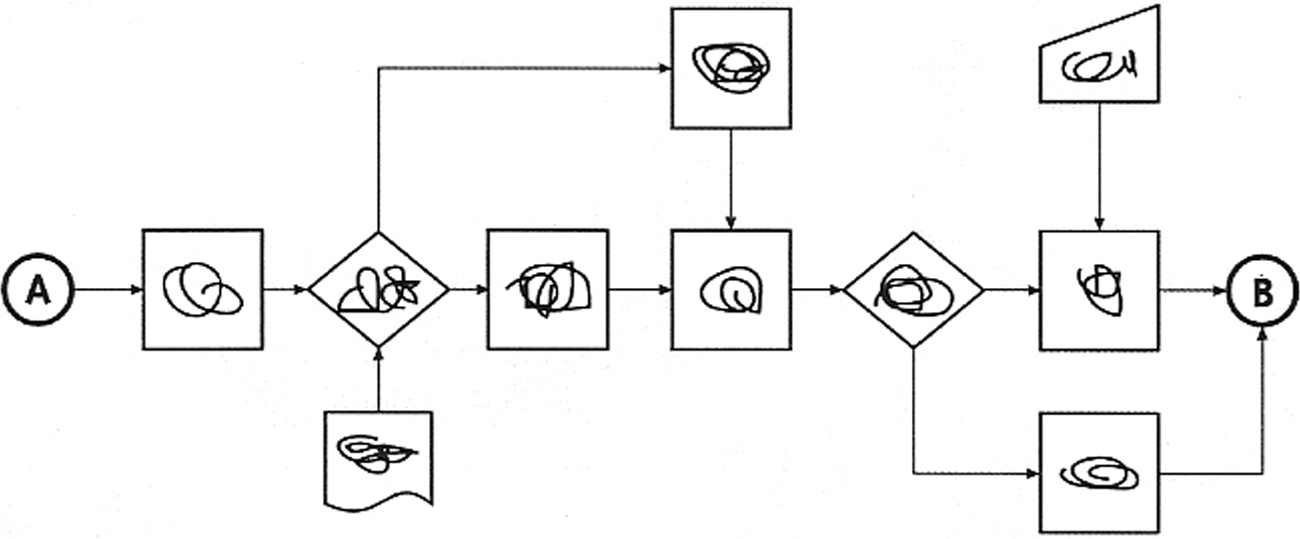

[Our method] stands for a systematic [way of innovating]. Usually when we talk about “systematic” this is the picture we have in mind [Alice shows fig. 1]: very structured, very systematic way of doing things. This picture is a bit scary. Where is the innovation in it? It looks very organized, yet where’s the passion? Where’s the place for coming up with something different? Yet raise your hand if you’ve ever participated in a brainstorming session [a number of participants raise their hands]. Usually a brainstorming session looks more like this, right? [Alice shows fig. 2; some participants laugh and nod in approval.] We know what the beginning of the process was; we know what the end was; we have no idea what happened during it. And this is not enough for us. … We don’t want just one inspirational moment or idea. We want to be able to repeat those ideas again and again and again. We want to be able to create a pipeline of ideas and not one kind of a brilliant solution once in a while. So this [fig. 2] is not good enough for us. So the question is how to be able to put this mess into a structure [Alice shows fig. 3], and this is actually what we will try to share with you in the next few days.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Referentially and predicationally, Alice seems to engage in a historical comparison between the method of innovation that is the focus of the workshop (henceforth “the Method”) and bainstorming, a system of innovation developed by the advertisement executive Alex Osborn in the mid-twentieth century (Osborn Reference Osborn1953). However, this comparison is also a densely regimented poetic structure that reflexively brings into being a macrosociological context of stereotyped series of opposed emblems of ideation and identity in the modern West, making this context, rather than some other group-relative truth, relevant to the interaction.

Note that Alice’s narrative is organized around two opposing clusters of terms. The first cluster consists of the following terms: “systematic,” “structured,” “organized,” “repeat that again and again and again,” “a stable pipeline of ideas.” Alice uses figure 1 to diagrammatically represent this cluster.

The second cluster consists of the following terms: “brainstorming,” “passion,” “mess,” “you have no idea what happened,” “one inspirational moment,” “one kind of a brilliant solution once in a while.” Alice uses figure 2 to diagrammatically represent this cluster.

This comparison reflexively brings into being a contrast between a professional ethos and a Romantic ethos, each ethos involving a different stereotypical mode of agency and a characterological aesthetic. Historically, the terms Alice associates with brainstorming derive from a Romantic ethos that conceptualizes creativity as a spontaneous and uncontrollable process, often accompanied by powerful sensations, ecstasy, and altered states of consciousness. In the middle of the eighteenth century, Romanticism institutionalized organic metaphors of the independent gestation and spontaneous growth of the exceptional individual’s inborn inner nature. According to Romantic ideologies of poetic inspiration, “an inspired poem or painting is sudden, effortless, and complete, [no longer] because it is a gift from without, but because it grows of itself, within a region of the mind which is inaccessible either to awareness or control” (Abrams Reference Abrams1971, 192). The association of creativity with uncontrollable passion and ecstasy received its most potent form within Romanticism in the eighteenth century Sturm und Drang movement—literally storm and stress—which posited extreme, uncontrollable emotions as a viable and commendable source of knowledge and action, in part as a reaction to neoclassical rationalism (Frank Reference Frank, Giles and Oergel2003). Brainstorming—the template for creative ideation that Alice contrasts with the Method—connotes these tropes not only via some of the principles that Osborn highlighted (e.g., “the all-importance of imagination” [Osborn Reference Osborn1953, 1–3], “no formula possible” [Osborn Reference Osborn1953, 118–20]), but also via its very name that invokes the Romantic Sturm—literally storm—hence brainstorming, and via the explanations that accompany this name that invoke the Romantic Drang—literally stress, as when Osborn claims that “ideas flow faster under emotional stress” (Osborn Reference Osborn1953, 181). Alice ultimately argues that brainstorming, despite its being based in “principles and procedures of creative problem-solving” (as stipulated in the full title of Osborn’s book), is too contingent for organizations predicated on a professional ethos that is associated with predictability, reliability, and rationality of action in the Enlightenment tradition—an ethos that Alice invokes by means of the terms found in the first cluster.Footnote 4

Alice, then, reflexively consolidates a broader historically specific landscape of two opposing narratives about modernity and the stereotyped emblems and roles associated with each narrative or ethos (see Wilf Reference Wilf2014a, 8–12), which most of her listeners are likely to recognize. Although Alice’s listeners—being members of large business corporations and holders of MBA degrees—would seem to be more familiar with, and are more likely to identify with and inhabit, the professional ethos as a basis for innovation, it should be noted that the Romantic ethos has become part of the fabric of the Western modern popular imagination, a taken-for-granted script about creative agency that is widely disseminated and circulated in different artifacts and narratives, and thereby reproduced (Taylor Reference Taylor1989, 376).Footnote 5 The predominance of the Romantic script about creative agency in the Western modern popular imagination does not mean that people are necessarily aware of its specific history. Rather, what is salient for people are the values and schemas of action that are associated with this script (and that are contrasted with those values and schemas associated with a “professional ethos”), which become periodically and reflexively reproduced and reified in communicative events such as the workshop that is the focus of this essay. A Romantic ethos, as any other group-relative truth such as the singularity of creativity and its products, is the result of interactional labor and discursive practices that take place in key institutional sites (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2013; Wilf Reference Wilf2014b). Illustrating what such labor and practices look like within the business corporation, as well as what their world-making consequences might be, is one of this essay’s key goals.

To illustrate the degree to which, within this corporate context, creativity and innovation are tightly coupled with a Romantic ethos and opposed to a professional ethos, consider a recent New York Times article titled “The Genius of Jobs” (Isaacson Reference Isaacson2011). At one point the author describes a dinner he had with Steve Jobs—one of Apple’s founders—and a few other people. When someone presented the attendees a riddle,

Mr. Jobs tossed out a few intuitive guesses but showed no interest in grappling with the problem rigorously. I thought how Bill Gates would have gone click-click-click and logically nailed the answer in fifteen seconds, and also how Mr. Gates devoured science books as a vacation pleasure. But then something else occurred to me: Mr. Gates never made the iPod. Instead, he made the Zune. So was Mr. Jobs smart? Not conventionally. Instead, he was a genius … his success dramatizes an interesting distinction between intelligence and genius. His imaginative leaps were instinctive, unexpected, and at times magical.

Bill Gates and Steve Jobs emerge from this vignette as two opposing, quasi-totemic figures that organize two radically distinct clusters of meanings around them. Bill Gates stands for “logically,” “rigorous,” and systematic problem solving—hence “click-click-click,” as well as “intelligence,” and “science,” whereas Steve Jobs stands for “unconventional,” “unexpected,” “imaginative leaps,” “instinctive,” “genius,” and “magical.” This basic opposition reflexively reifies an opposition between a professional ethos and a Romantic ethos, respectively. In the New York Times article there is never any doubt about who of the two figures epitomizes the spirit of innovation as well as its material consequences (here indexed by the opposition between the failed and decommissioned Zune and the highly successful iPod) and which ethos—a Romantic or a professional—aligns with this spirit. In describing Gates and Jobs as quasi-totemic figures, I suggest that they have become emblematic figures of identity that serve as cardinal points of orientation for many people (Durkheim Reference Durkheim1995, 207–41; Agha Reference Agha2006, 233–77). The characterological aesthetic of which these two opposing totemic figures are emblematic finds crystallized expression in commercial videos produced by Apple that show two young males—one representing a PC and looking very much like a young Bill Gates, and one representing a Mac and looking very much like a young Steve Jobs—interacting with one another.Footnote 6 All the presumably “boring” qualities mentioned in the New York Times article and associated with Gates, and all the presumably “cool” qualities mentioned in the New York Times article and associated with Jobs, find aesthetic expression in these videos: the clothes, the bodily demeanor, the hairstyle, the speech, the “sexiness” or the lack thereof, and of course the specific features that a Mac has versus a PC—the PC’s features amounting only to a calculator and a clock according to one video; one can almost hear the dreadful “click-click-click” sound of Gates solving the riddle according to the New York Times author.

The challenge facing the facilitators, then, should be understood on two levels. On one level, they must teach the participants a number of innovation techniques in a relatively short time frame and in a way that would convince them that there can be added value to buying the consultancy group’s services. On another, tightly related level, they must reframe and put a different spin on the opposition between a Romantic ethos and a professional ethos—no mean feat given the stereotypical meanings associated with each ethos. Here I focus on the second level. I argue that throughout the workshop the facilitators orchestrate densely multilayered and multimodal discursive practices that dynamically figurate differences in value between the two kinds of ethos, as well as suggested transformations in the participants’ role-inhabitance with respect to innovation—from their role-inhabitance of a Romantic ethos at the beginning of the workshop to their entailed role-inhabitance of a professional ethos at the workshop’s end.

Consider Alice’s opening statement, which I quoted above. Note that her comparison between brainstorming and the Method does not simply outline a synchronic, atemporal system of presupposable oppositions. Narratives have a durational real-time aspect; they progress from one point to the next on the temporal axis. This fact allows narrators to dynamically figurate or indexically entail the idea of development or a hierarchical and unequal relationship between different terms without, or in addition to, explicitly spelling out this idea or relationship (Ochs and Capps Reference Ochs and Capps1996, 26; Ochs Reference Ochs and Duranti2006). The “earlier-to-later in emerging text-structural metricalization” thus becomes “an icon or diagram of process” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein and Sawyer1998, 274), one that can have concrete implications for participants’ role-inhabitance.

Alice begins her narrative with the Method by saying, “[Our Method] stands for a systematic [way of innovating].” She then shows figure 1, which presumably diagrams a systematic mode of thinking, immediately suggesting that this diagram may be antithetical to what most people would normally associate with innovation. She then proceeds to brainstorming as the method of creative ideation that her listeners are more likely to associate with innovation, showing figure 2 and spelling out the limitations of brainstorming in terms of its lack of reliability and predictability. She then comes back to the Method, which promises “to create a pipeline of ideas and not just one kind of a brilliant solution once in a while,” showing figure 3.

Note that figure 3 is figure 1 encompassing figure 2. In figure 3 each neat geometrical shape shown in figure 1 encompasses a little “storm,” that is, a miniaturized version of that big storm that Alice mentions earlier in her narrative and that is shown in figure 2. Now each such “storm” is well controlled and can be deployed rationally and effectively (as implied by the straight lines and angles that connect the geometrical shapes to one another in fig. 3). The successive arrangement of figures 1, 2, and 3, then, diagrams, or is an icon of, the process of the Method encompassing brainstorming and harnessing its unruly chaotic nature into a fruitful way of routinizing innovation. Note that this encompassment of brainstorming by the Method, which figure 3 diagrams in two-dimensional space, is also diagrammed in time, that is, on the temporal axis of Alice’s narrative, in that the Method is addressed both at the narrative’s beginning and end, thus encompassing brainstorming, which is addressed at the narrative’s middle, from both sides.

Most important, Alice indexically entails, and thereby translates the above encompassment of brainstorming by the Method into, transformations in the participants’ role-inhabitance, from their role-inhabitance of a Romantic ethos via brainstorming at the beginning of the workshop to their role-inhabitance of a professional ethos via the Method at the end of the workshop. She does so by means of the strategic use of deictics, especially personal pronouns (see Brown and Gilman Reference Brown, Gilman and Sebeok1960; Errington Reference Errington1988; Wortham Reference Wortham1996). Alice begins her narrative by saying, “[Our Method] stands for a systematic [way of innovating]. Usually when we talk about ‘systematic’ this is the picture we have in mind,” at which point she shows the participants figure 1. Alice’s use of the deictic “we” at this point is only partially inclusive, that is, it only partially includes the participants because the workshop has just begun and the participants have not yet become familiar with the Method and with a “systematic” way of innovating. The deictic is inclusive of the participants only to the extent that Alice suggests that the participants might be vaguely familiar with the general contours of what a systematic procedure might look like, as diagrammed in figure 1.

When Alice turns to discussing brainstorming, she shifts to using the deictic “you.” She asks the participants to “raise your hand if you’ve ever participated in a brainstorming session,” after which a number of participants raise their hands. When she shows them the chaotic figure that presumably diagrams brainstorming (fig. 2), some of the participants laugh and nod in approval. Alice thus indexically entails the participants as inhabiting the Romantic ethos via brainstorming at the beginning of the workshop. Indeed, in a different session later that day, Tom, another of the facilitators, repeated this specific indexical entailment by saying that “it’s called brainstorming because there’s this little storm going on in your brain when you’re doing it. And remember that chaotic form [i.e., fig. 2]: you know where A is and where B is but there’s a lot of mess going on between them, pretty much characteristic of the storm that’s going on.” Note that in addition to repeatedly using the deictic “you,” Tom indexically entails the participants as inhabiting brainstorming (and a Romantic ethos) by suggesting that brainstorming literally “inhabits” the participants, for the “little storm” is now “going on” in the participants’ “brain,” no less! Alice’s and Tom’s metricalized use of the deictics “we” and “you” thus indexically entails a difference in the facilitators’ and the participants’ role-inhabitance at the beginning of the workshop.

Significantly, after associating the participants with brainstorming, Alice immediately shifts back to using the deictic “we” to enumerate the limitations of brainstorming and to describe the alternative mode of ideation that the Method offers, only this time this deictic can be interpreted as being inclusive of the participants: “We know what the beginning of the process was; we know what the end was; we have no idea what happened during it. And this is not enough for us. … We don’t want just one inspirational moment or idea. We want to be able to repeat those ideas again and again and again. We want to be able to create a pipeline of ideas and not one kind of a brilliant solution once in a while. So this [fig. 2] is not good enough for us. So the question is how to be able to put this mess into a structure [Alice shows fig. 3].” By repeatedly using the deictic “we” when speaking about the Method (and about the limitations of brainstorming) at the end of her narrative and in terms of goals that her listeners are likely to identify with (e.g., “We want to be able to create a pipeline of ideas and not one kind of a brilliant solution once in a while”), Alice incorporates the participants, to whom she earlier referred with the deictic “you” when discussing brainstorming, into the role inhabited by the consultancy group. Her last sentence, which resumes the deictic difference between “we” and “you” (“and this is actually what we will try to share with you in the next few days”), reestablishes the knowledge difference between the facilitators and the participants after the indexically entailed identity of role-inhabitance. In itself, the deictic structure that organizes the narrative as a whole provides only a minimal interactional framework (Wortham Reference Wortham1996, 344), but inasmuch as it coheres with the other forms of figuration I have discussed above, it provides and is provided with added interactional force.

Alice’s narrative is thus a multimodal and multilayered dynamic figuration of the encompassment of brainstorming by the Method (see fig. 4), one that indexically entails transformations in the workshop participants’ role-inhabitance during the workshop, namely, from their role-inhabitance of a Romantic ethos via brainstorming at the beginning of the workshop into their role-inhabitance of a professional ethos via the Method at the end of the workshop. It is an icon or diagram of the process of the participants’ coming to inhabit the Method and the philosophy of innovation it represents. Its goal—to convince the participants to buy the services of the innovation consultancy group—is similar in nature to the goals of other kinds of ritual events, namely, to precipitate in the “real” world the processes diagramed in the “bounded microcosm of ritual social-spacetime” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Senft and Basso2009, 273; see also Stasch Reference Stasch2011, 160–68).Footnote 7

Figure 4.

A Story of Corporate Origins

Different communicative events that took place in other sessions during the workshop formed the basis for the production of interactional texts very similar to the one I have just described. For example, in the first session of the workshop’s second day, Tom addressed the participants with the following story, which I quote in detail:

This morning’s learning starts out with a story. It’s not a very well-known story. It’s about an important event in world history [Tom laughs]. Maybe I went overboard with the buildup, but it’s a story of how the Method was born. Maybe it’s not world history but it’s important to us. It all started in the early 1990s. Two students were studying in a very interesting program—a joint program for aeronautical engineering and marketing. Quite interesting. … And as good friends do, especially when they’re studying for their doctoral dissertations, they went out one evening, … had a good time, and they finished their going out very late at night. They got into their rental car that they had rented for a short while and they said, “OK, it’s really late, we gotta get back to the city, let’s take a shortcut.” They started driving home on an off road in the middle of a nowhere area and all of a sudden they got a flat tire. It happens, especially when you’re looking for shortcuts and maybe having too much to drink. So they are aeronautical engineers—they said “no problem changing a flat tire.” So what did they do? Has anyone ever had to change a flat tire? So you pretty much know. What they did is they opened up the trunk … they took out the jack, they positioned it next to the tire … they took out the cross wrench to affix to the bolts, they started to [release] the bolts to remove the old tire. They removed the first bolt and the second bolt and then they got to the third bolt and it wouldn’t budge. And with closer inspection with their flashlight they saw that it was rusted on, and although they started jumping on the cross wrench and both of them pushing at the same time it just wouldn’t turn. That was the situation. Do you agree that there was a problem involved there? Would you characterize this as a problem if you encountered the story? So this morning we are going to be learning [our] approach to problem solving. It’s completely new. It’s a different approach to problem solving. And we’ll learn it through some of the things that they noticed during this really important event, which they later studied and tested in order to form the basis, the foundation of the Method. So now in pairs, just as you’re sitting [Tom divides the participants into pairs], jot down a few thoughts on what can be done, how to solve this problem.

Tom’s story can be considered to be what anthropologists call an origin or creation myth, that is, a story that “tells how, through the deeds of Supernatural Beings, a reality came into existence, be it the whole of reality, the Cosmos, or only a fragment of reality—an island, a species of plant, a particular kind of human behavior, an institution.” Such myths “disclose [the Supernatural Beings’] creative activity. … [They] describe the various and sometimes dramatic breakthroughs of the sacred … into the world” (Eliade Reference Eliade1998, 5–6). Although origin myths are often associated in the Western popular imagination with nonmodern, “archaic” societies, they pervade different kinds of cultures, including business corporate cultures. Note that Tom reflexively frames his story as an origin myth by saying, “It’s about an important event in world history. … It’s a story of how the Method was born.” Indeed, not only is Tom’s story about the origin of an “institution,” it is also literally about a “breakthrough”—a solution to a problem, which promises to be paradigmatic of all innovative solutions to all problems.

Origin myths typically have a number of features. One of their important functions is to explain and naturalize key principles that structure the world. These are the basic coordinates, forces, and overall logic that underlie the relevant universe for a specific culture. The origin story of the Method performs a similar function. Thus after the participants worked in pairs for two minutes, Tom solicited from them a few solutions. He then revealed the solution that the “founding fathers” came up with: “I would like to suggest another solution that typically doesn’t come up, and the solution is as follows: let’s use the jack to remove the bolt. The jack lifts the car by providing a lot of leverage. What do we need to move the bolt? Leverage. So maybe we can place the jack under the wrench and use the jack to turn the wrench. This is the solution they came up with.” Tom then explained that the reason people do not come up with this innovative solution in particular, and innovative solutions in general, is because they do not stay within the boundaries of their existing resources, that is, they do not abide by one of the key principles of the Method, which stipulates that when you are trying to solve a problem or to innovate the only resources you can use are the resources you already have. Another reason people can’t find the proper solution is that they tend to think that objects can only perform their present function—they can’t think of alternative functions the same object can perform, as in the case of the jack. In this way, Tom uses the origin myth to naturalize two key principles that underlie the Method.

To be sure, the capacity of origin myths to naturalize key principles that also apply to the present can be limited because an origin myth typically “relates an event that took place in primordial Time, the fabled time of the ‘beginning’” (Eliade Reference Eliade1998, 6). Such an event is thus separated from the present by a radical temporal disjuncture. The origin myth and the present can be said to represent distinct time-space configurations, or chronotopes (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1996). However, as scholars have long argued, when narrators narrate events that took place in a past understood to be radically different from the present they can align the two chronotopes as coeval by using different metapragmatic features (Perrino Reference Perrino2007), thus closing the temporal gap between the narrating event and the narrated event to achieve specific communicative goals (Jakobson Reference Jakobson, Waugh and Monville-Burston1995). Such chronotopic alignment is precisely what the ritual enactment of origin myths typically aims for. This alignment can have significant experiential dimensions for members of a culture who desire to “[re-enact] fabulous, exalting significant events … [to witness] the creative deeds of the Supernaturals … to re-experience that time … to meet with the Supernaturals and relearn their creative lesson” (Eliade Reference Eliade1998, 19, emphasis added; cf. Urban Reference Urban2001, 91; Wilf Reference Wilf2012). Similarly, note that by asking the participants to try to find a solution to the problem of the flat tire “in pairs,” Tom in fact transports the participants into the chronotope of the origin myth so that they can reenact the deeds of the original pair of “founding fathers” when they tried to find a solution to an identical problem and thus learn what literally purports to be a “creative lesson.” Thus, although the participants are not members of Tom’s business corporate culture, and hence it can be safely assumed that the origin story is unlikely to be as meaningful for them as for Tom and his fellow consultants, it is also plausible that this reenactment does bring the participants closer to the “creative lesson” that the origin story epitomizes, such as the two basic principles of the Method.

However, more important for my discussion is the relation of this origin story to an earlier session in the workshop. A common feature of myths is that they do not merely describe and naturalize the founding structure and ontological principles of the world but also provide a narrative that, as Malinowski suggested, “safeguards and enforces morality” (Malinowski Reference Malinowski1992, 101). In an earlier session, Gabriella, another facilitator, explained that the Method is meant to counteract people’s instinctive tendency to break away from the closed world of their available resources, as well as their tendency to immediately replace broken resources with new ones rather than to think of new functions that these broken resources can perform. She added:

What we are trying to offer here is the path of most resistance, as opposed to the path of least resistance [that corresponds to] the principle from nature—that water will always take the path of least resistance [in the same way that] our way of thinking and our cognitive processes [do, where] we will always try to find the shortest way from point A to point B. But the shortest way will usually also be the most fixated one, and the path of most resistance is trying to encourage us to explore new ways of generating ideas. … So [the Method] is sometimes counterintuitive when it comes to trying to improve things and making things better. [It is] a very effective way to break fixedness.

I suggest, first, that at the same time that this vignette referentially and predicationally conveys information about our thinking processes by comparing them to natural processes like the flow of water, it, too, also reflexively consolidates the historically specific opposition I discussed in the previous section, that is, that between a professional ethos and a Romantic ethos. For, as Charles Taylor has argued, the Romantic ethos poses “nature as source” of action (Taylor Reference Taylor1989, 355–67). It celebrates the independent gestation and spontaneous growth of each individual’s inborn “inner nature” (Taylor Reference Taylor1989, 185–98). It demands that each person listen to and realize his or her own “voice of nature” (Taylor Reference Taylor1989, 305–67; see also Wilf Reference Wilf2011). As I mentioned before, it is for this reason that Romantic ideologies of poetic inspiration held that “an inspired poem or painting is sudden, effortless, and complete … because it grows of itself” as the creative individual’s inborn inner nature (Abrams Reference Abrams1971, 192, emphasis added). Bearing in mind that organic metaphors of creativity are widespread today among modern Western individuals, even if these individuals are not always aware of these metaphors’ intellectual roots in Romanticism, I suggest that when Gabriella says that the Method offers “the path of most resistance,” which is the opposite of “the principle from nature—that water will always take the path of least resistance [in the same way that] our way of thinking and our cognitive processes [do, where] we will always try to find the shortest way from point A to point B,” her purpose is not to engage in hydraulics. Rather, this denotational text, too, aligns the Method with a professional ethos and reflexively contrasts it with a Romantic ethos.

Second, against the backdrop of such alignment and contrast, the fact that Tom, in the origin story, narrates the flat tire as a result of the two heroes taking “a shortcut” becomes significant. To reiterate the way Tom puts it in the origin story: “They started driving home on an off road in the middle of a nowhere area and all of a sudden they got a flat tire. It happens, especially when you are looking for shortcuts and maybe having too much to drink.” This reference to taking a shortcut indexes precisely what Gabriella said earlier about cognitive fixedness: “[in the same way that] our way of thinking and our cognitive processes [do, where] we will always try to find the shortest way from point A to point B. But the shortest way will usually also be the most fixated one.” Thus the succession of Gabriella’s remarks and the origin myth of the Method indexically entails a moral lesson based in the opposition and hierarchy between a Romantic ethos and a professional ethos. This moral lesson stipulates that it is precisely following “the principle from nature” or a Romantic ethos—one’s intuitions, brainstorming, and everything that falls within this cluster—that is likely to produce problems (such as a flat tire) because it does not involve carefully thought out principles of action—it presumably takes place “within a region of the mind which is inaccessible either to awareness or control” (Abrams Reference Abrams1971, 192).Footnote 8 Conversely, it is the Method and a professional ethos—the application of the scientifically rigorous innovation tools developed by the consultancy group—that can systematically lead to breakthrough solutions (in the form of profitable products and services), for note that Gabriella argues that “the path of most resistance is trying to encourage us to explore new ways of generating ideas. … So [the Method] is sometimes counterintuitive when it comes to trying to improve things and making things better. [It is] a very effective way to break fixedness.”Footnote 9

This moral lesson represents an ironic and even radical ideological reversal. Whereas a dominant contemporary ideology of the modern, Romantic self stipulates that following one’s own nature and intuitions is the surest way of breaking free from societal conventions that everywhere hinder individuals from realizing their unique and creative potential, the facilitators suggest that it is precisely “the principle from nature” that becomes the source of various kinds of “fixedness” and conventions that prevent corporate members from coming up with unique and innovative ideas for new products and services. Conversely, it is the Method—a predesigned set of rules, procedures, and, indeed, conventions—that now plays the recuperative role of realizing the potential of one’s business corporation to innovate. Inasmuch as “nature as a source” has become a taken-for-granted modern normative ideal of creativity, the Method indeed becomes “counterintuitive,” as Gabriella suggests, although not because it does not align with a key principle of hydraulics, as it were—that is, how fluids behave, water always taking the path of least resistance, and so on and so forth—but because it posits a predesigned, rational template and procedure as the key to innovation.

Divide and Conquer

A final example of similar discursive processes that took place during the workshop has to do with the ways in which the Method is supposed to be applied by a group of people in real-time innovation sessions in concrete corporate settings. I argue that the actual application of the Method is conducive to the real-time inhabitance and enactment by participants of the contrast between a professional ethos and a Romantic ethos, as well as the “moral lesson” I described in the previous section. In this way, the moral lesson becomes a concrete experiential and inhabitable reality (and spectacle) for everyone involved, a fact that contributes to its solidification and naturalization.

During a session on the workshop’s third day, Tom explained that whenever the Method is executed by a team of people working on a specific project it is crucial to make sure that the following three roles are taken by three different people: the owner, the facilitator, and the documenter. The owner is “the person to whom the project or issue belongs and that can make decisions along the way [such as] ‘yes, this is a good direction,’ ‘no, this is completely ridiculous, I know most about it and I’m in charge.’” The facilitator “is the person who decides on what tool we should work with on this topic and is in charge of the process, in charge of making sure that we’re working properly with the Method, that we’re applying the tool properly.” The documenter is “somebody who’s writing down the ideas. He is not writing down [everything] that’s going on during the discussion but he has to make sure that each time an idea comes up it’s captured so it doesn’t get lost.”

One reason for this trichotomy of roles—especially for the separation of the roles of owner and facilitator—has to do with the way in which the Method actually purports to produce its effects. The Method is based in various procedures of altering the form of existing products and services and then trying to figure out the new functions these altered forms might be able to perform. Because of the nature of the alterations—for example, removing the most important component from an existing product—the altered product often appears to be bizarre and meaningless, especially for those members of the corporation who are most familiar with the existing product such as the people who were in charge of developing it. Those people, who are most likely to take the role of the owner in innovation sessions that concern that product, are also the people who are most likely to experience and express resistance to the process of altering the product. Hence it is important that there is someone in charge of the accurate application of the Method—the process—who is not the owner. Tom explained this rationale by ascribing fixedness to the owner time and again. In one session he said: “One of the good reasons the facilitator isn’t the owner is because ownership has a lot more fixednesses, assumptions that are built in, and the facilitator can take a step back and properly apply the process by avoiding those fixednesses.” In another session he added: “It’s usually the owner who says ‘forget it, it’s not going to work, that’s not going to work,’ because they are prefiltering the ideas. And usually it’s an excellent indication that there’s fixedness. … It means there is fixedness involved there and that’s why it’s the facilitator’s role to really push, to say: ‘OK, we understand that it doesn’t really make sense right now … but we are going to give it a chance … and if we don’t find something we can move on, but it will help us really break that fixedness.’”

Although I do not suggest that these considerations, which pertain to the concrete nuts and bolts of the process of innovation, are invalid, I argue that the trichotomy of roles has another function, namely, to naturalize the ideological inversion and moral lesson that I have discussed earlier. It is significant that Tom and Gabriella framed the owner’s fixedness in terms of emotional involvement that connotes proximity to and entanglement with the product that needs to be innovated, for this framing aligns the owner with a Romantic ethos that, as I have explained above, emphasizes emotions as viable sources of action. It is similarly significant that they framed the facilitator who is in charge of the “process” in terms of dispassionate, distant observation, for this framing aligns the facilitator with a professional ethos that connotes methodical and dispassionate rationality—remember Tom’s description of the facilitator as being able to “take a step back.” Gabriella added: “our advice would be that, if you can, don’t be the owner of the topics that you facilitate. … Since we are so attached to our topic we might be the ones who are the most fixated about it. … I think that [the owner is] so emotionally involved in a session, as opposed to the facilitator who can actually look at things from a distance and manage the process.” Tom concurred: “there are certain problems that come up when you’re both the facilitator and the owner. As the owner you get excited about an idea and that can stifle the discussion and not allow for other directions to come out. So it’s even more complicated when you’re also the facilitator trying to lead the group to different directions.” These are almost textbook applications of the macrosociological context of stereotyped series of opposed emblems of ideation and identity that I have discussed earlier, which contrasts a Romantic ethos with a professional ethos. It is precisely such periodic textbook applications that consolidate this macrosociological context as a group-relative truth to begin with. By arguing that the facilitator is the one who is able to “take a step back” and thus avoid different kinds of fixedness, the workshop facilitators suggest that a professional ethos, with which the Method is aligned, holds the key to successful innovation.

A theoretical framework that can shed further light on the ritual semiotic function of the trichotomy of roles is Goffman’s theory of participation framework, or the kind of participants who might be involved in a communicative event (Goffman Reference Goffman1981). Goffman has argued that the speaker can be decomposed into, among other roles, the animator—the person actually producing the words or sentences during an interaction; the author—the person who composes these words and sentences; and the principal—the person who is socially responsible for these words or sentences and on whose behalf they are uttered. Goffman’s framework has pointed to the complexity of role alignment in what on the surface often appears to be a simple dyadic interaction that involves only two participants: the speaker and the hearer.

When applied to the roles of owner and facilitator, this theoretical framework points to an important difference between the owner, who animates and authors himself, that is, who is the principal of and responsible for what he or she says; and the facilitator, who animates and authors for a principal different from himself, that is, the Method. This difference is consequential because inasmuch as the owner represents the union of animator, author, and principal, he epitomizes a specific ideal of authenticity and nonalienability that are the hallmarks of the Romantic self (Taylor Reference Taylor1992; cf. Wilf Reference Wilf2013a). Conversely, inasmuch as the facilitator animates and authors on behalf of someone or something else, he represents a form of alienation of the self, its usurpation by something external—in this case, an abstract, reified rational process, no less (Lukacs Reference Lukacs1972; Horkheimer and Adorno Reference Horkheimer and Adorno2002). However, in accordance with the kind of ideological reversal I have discussed above, in real-time innovation sessions in which participants took these three roles and interacted with one another, the authenticity of the self in the owner’s case proved time and again to be a hindrance to innovation because it led the owner to follow all kinds of fixedness whereas it was the split of the self in the facilitator’s case that became the enabling factor of innovation. By taking up these different roles, then, participants had the opportunity to experience and inhabit firsthand this difference, and also to witness it in others.

For example, in one innovation mini-session that took place toward the end of the workshop, in which I participated as a documenter, Jill, the owner, presented a problem: how to innovate an existing product her corporation produces, namely, packaged jam. The team applied one of the innovation tools they had learned the previous day, which amounts to subtracting one of the crucial components of the existing product and figuring out what function the altered product might be able to perform. Angela, the facilitator, suggested taking away the glass jar in which the jam is packaged. She then wanted to list the benefits of having a jam without a jar, as this process requires, when Jill intervened:

Jill Hang on. We need to determine what would be the alternative package before listing the advantages. We have to understand what the packaging would look like.

Eitan It’s without a package.

Jill But there’s got to be some package!

Angela No, that’s our altered product. That’s the idea. We have to stick to it.

Jill All right, so if you lose the jar you have to lose the lid, too.

Angela Do you? Tom said that we don’t have to do anything; that we should stay with the altered product and list the advantages.

Jill Why would you have a lid?

Angela Let’s think about it. It’s part of the challenge. If you don’t have a jar what would you put a lid on, what would you put your label on? What could we do with them? We need to think about that.

Note the ways in which Jill, the owner, inhabits and displays to the other participants various kinds of fixedness such as the certainty that packaging is essential or that the lid and the label cannot perform any function without the jar. These are precisely the kinds of fixedness that the origin story describes, which the pair of “founding fathers” managed to overcome. Note also the ways in which Angela, the facilitator, manages to resist these kinds of fixedness simply by animating the Method. After a few minutes, Angela came up with an idea that Jill agreed was both interestingly innovative, feasible, and potentially profitable, in part because of the significantly reduced costs entailed by the subtraction of the packaging.Footnote 10

At the end of a number of mini-sessions during the workshop, in which each participant had the opportunity to experiment with different roles, Tom and Gabriella asked the participants to share their experiences and lessons. Two participants, Angela and Chris, offered the following commentaries, which resonated to some degree with the commentaries offered by a number of other participants and which point to the effect that inhabiting and watching other participants inhabit in real time the roles of owner and facilitator had on the participants:

Angela I had a great team. The thing that I want to call out is the facilitator role [taken by another participant] challenged my thinking early on because I was fixed into thinking what the end goal needed to be and the question [the facilitator asked] was: “Wait, hold on, you’re already thinking about the solution. Let’s first get into the process.” It was, “oh my gosh, I really am!” And it was really valuable just to get back into it.

Chris I like it when I, as a project manager, am not the facilitator because I noticed that I come with my own fixedness and it is good that someone else facilitates the session to prevent that from happening.

These commentaries suggest that by inhabiting in real time, and witnessing other people inhabiting in real time, the roles of the owner and the facilitator, some of the participants internalized the lesson that being an owner—a position that unites animator, author, and principal—entails a lot of fixedness, whereas being a facilitator—a position that animates and somewhat authors the Method—results in open-mindedness and fresh ideas. Inasmuch as the owner invokes a Romantic ethos, and inasmuch as the facilitator invokes a professional ethos, this lesson indexically entails a hierarchy between a Romantic ethos and a professional ethos, in which the latter becomes superior to the former as a successful and reliable framework for innovation. In so doing, it encourages transformations in the participants’ role-inhabitance from one ethos (the Romantic) to another (the professional).

Conclusion: Toward an Anthropology of Ritual Semiosis in the Business Corporation

I have discussed the ways in which some participants noted their, and others’, fixedness when they took the role of owner, and the innovative ideas they and others were able to generate when they took the role of facilitator animating and authoring the Method. One would want to read Angela’s and Chris’s commentaries as evidence of their having undergone a quasi-conversion following their inhabitance of the “moral lesson” and watching other participants inhabiting it. This would align with my argument that the workshop functions as a ritual event that is meant to indexically entail—that is, to effectuate—transformations in the participants’ role-inhabitance. At the same time, it is important to note that these commentaries themselves constitute a specific genre in such workshops, during which participants are often asked to share their “learnings” following specific exercises, and consequently provide precisely the kind of commentaries they are expected to provide for reasons that do not necessarily suggest any long-term transformations in their role-inhabitance. To assess the existence of such transformations even in a cursory fashion it is thus necessary to look beyond the immediate ritual event.

In conversations I had with a few of the participants outside the specific sessions, I have recorded indications that at least some of the participants have come to inhabit in a more permanent fashion the role into which they were indexically entailed throughout the workshop. Thus at dinner, when I explained to Garry, an innovation architect in a company of 4,000 employees and annual revenues of about $1.3 billion, that my interest in the workshop is motivated by my desire to understand the culturally specific meanings of creativity in the twenty-first-century business corporate environment, he immediately interjected:

What we are doing here has nothing to do with creativity. The people I supervise are not creative—this is not some sleek software company. They are not creative. You know, I already attended another workshop given by these guys [referring to the innovation consultancy group that organizes the workshop] and then I taught my people some of these tools and it was amazing: one, two, three; step, step, step—my people came up with amazing solutions. So there is this process and it works. It is mechanical: this is the idea. You don’t need to be this amazing genius. This is the idea of bringing the culture of innovation into the organization.

Garry’s firm rejection of the notion of creativity is motivated by his belief that innovation in many contemporary organizations has more to do with ordinary people following steps in a procedural way than with creative visionaries taking imaginative leaps. Note the ways in which Garry’s definition of innovation aligns with a professional ethos as stereotypically depicted in the New York Times article I have discussed above (Isaacson Reference Isaacson2011), which associates this ethos with the image of Bill Gates, and which contrasts it with the image of Steve Jobs that, as I have argued, represents a Romantic ethos:

Mr. Jobs tossed out a few intuitive guesses but showed no interest in grappling with the problem rigorously. I thought how Bill Gates would have gone click-click-click and logically nailed the answer in fifteen seconds, and also how Mr. Gates devoured science books as a vacation pleasure. But then something else occurred to me: Mr. Gates never made the iPod. Instead, he made the Zune. So was Mr. Jobs smart? Not conventionally. Instead, he was a genius … his success dramatizes an interesting distinction between intelligence and genius. His imaginative leaps were instinctive, unexpected, and at times magical.

Compare Garry’s description of the Method as “one, two, three; step, step, step” and as being “mechanical” with the New York Times description of Bill Gates going “click-click-click and logically [nailing] the answer in fifteen seconds.” Gary, I suggest, has come to inhabit the emblematic figure of identity that is Bill Gates, but whereas in the New York Times article the solutions associated with Gates are described as boring and not innovative, Garry argues that when his employees applied the Method they “came up with amazing solutions.” Whereas the New York Times article celebrates Jobs for being a quasi-Romantic “genius” of ex nihilo creativity and suggests that such genius is a condition of possibility for innovation, Garry argues that “you don’t need to be this amazing genius” to bring “the culture of innovation into the organization.” Most important, the fact that Garry had already attended a similar workshop given by this consultancy group and consequently bought its services is perhaps the most suggestive indication of his coming to inhabit the role into which the facilitators indexically entailed the workshop participants via the discursive processes I have analyzed here, and via other discursive processes that I did not have the space to discuss in this essay.

Such shifts in role-inhabitance become mostly inexplicable if we fail to attend to the ways in which the production of denotational coherence during key communicative business corporate events becomes the basis for the production of interactional coherence. For, note that each communicative event in each of the three sessions, which I have discussed above, forms the basis for the production of a very similar interactional text—all interactional texts thus indexically iconizing one another across the sessions. In this sense, the reflexivity of the corporate reflexive metacultural processes I have analyzed in this article should be understood as the result of not only the fact that at stake are discursive practices that explicitly refer to a specific business corporation’s culture but also, and more importantly so, of the fact that they are characterized by a dense poetic structure that, as Jakobson has argued, is essentially reflexive in that it focuses attention to itself (Jakobson Reference Jakobson and Sebeok1960). Here, too, we find a version—albeit a mild one—of a “hypertrophied, reflexively calibrated metasemiosis” (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Senft and Basso2009, 272), that is, numerous layers of figuration in various modalities, which are laminated on one another. At stake, I argue, is business corporate ritual semiosis. Business corporate ritual events, too, dynamically figurate the concrete effects they are meant to have in the corporate world and it is precisely by virtue of such figuration that they are meant to have them. Scholars of organizations and business corporations have much to gain from approaching corporate rituals, narratives, myths, and slogans as discursive processes whose consequences—both intended and unintended—emanate from the specific modes of semiosis in which they are anchored and of which they are productive.