The translation of Upaniṣads from Sanskrit into English by British indologists marks a major accomplishment in the history of comparative philology and Indian studies, but the transmission of knowledge in Vedic discourse requires some understanding of traditional categories of Vedānta. In an effort to comprehend the esoteric, symbolic meaning, or philosophy of the Upaniṣads, since the late nineteenth century indologists have commenced classifying the knowledge portion (jñāna-kāṇḍa) at the end (anta) of the Vedas into various divisions, such as Pure Vedānta Upaniṣads, Yoga Upaniṣads, Sannyāsa Upaniṣads, Śiva Upaniṣads, Viṣṇu Upaniṣads, principal, major, or classical Upaniṣads, and minor Upaniṣads.Footnote 1 Orientalist schemes have also been produced according to historical periods and literary structure. Whenever indologists refer to Pure Vedānta, or principal, major, or classical Upaniṣads, there is often an accompanying attempt to establish an equation between the self (ātman) and nondual reality (brahman).Footnote 2 While acquiring knowledge of brahman (brahmajñāna) is central to the teaching tradition (sampradāya) of Advaita Vedānta, however, it should not be assumed that brahmajñāna can be deduced as the fundamental doctrine of any ready-made conceptual world sustained by indigenous collections of Upaniṣads.

Despite laboring profusely in the Yoga tradition, some modern theologians of Vedānta may still want to transmit brahmajñāna, but with Hindus claiming to possess over one thousand Upaniṣads it would be simply pious to claim that’s all they intend (Sastri Reference Sastri1898). The existence of some, such as “Allah Upaniṣad,” also raises serious questions about their ongoing revelation (Müller Reference Müller1879, lxvii; Krishna Reference Krishna1991, 96). As Olivelle explains, nevertheless, “in the eyes of the believers, all Upaniṣads have the same authority. They are eternal and transcend history” (Reference Olivelle1992, 4). Fortunately, the transmission of knowledge in traditional Vedānta and cognitive hypotheses for the acquisition of brahman are not constrained by the timeless production of Upaniṣads. Before attempting to explain sociopolitical modes of codification, as Todorov explains, it is first necessary to establish “linguistic properties of preliterary materials” within language (e.g., delineate relevant utterances in different registers of discourse) ([Reference Todorov and Howard1981] Reference Todorov and Howard1987, 20). For linking Vedic truth-statements (mahāvākyas) to the Advaita sampradāya, moreover, nonlinguistic properties of communicative events should be clearly distinguished from some abstract reality inscribed in the domain of symbolism.

While considering the codification of genres in discourse Todorov (Reference Todorov and Porter1990) sought to explain their systematic origin. One either starts with an observed genre and attempts to trace the series of transformations, inversions, displacements, and combinations of speech-acts from which it derived, or perhaps the codification of discursive properties coincides with a speech-act that has a nonliterary existence, but in either case the interpretation of utterances at the root of all discourse genres is determined by the “enunciatory context” of the sentence uttered (Todorov Reference Todorov and Porter1990, 16–26). Defining a genre as the codification of discursive properties, given all possible codifications of discourse, Todorov suggests that the choices a society makes obligatory for the historical existence of genres constitute the norms governing its system of genres, and “the genres of discourse, as we see, depend quite as much on a society’s linguistic raw material as on its historically circumscribed ideology” (10). Such an idea may explain why an Upaniṣad is popular in a society at one time and a Purāṇa (myth) at another, but it is hard-pressed to account for the ongoing, participatory context governing the use of mahāvākyas in episodes of traditional interaction. Without reducing Upaniṣads to discursive genres nor getting lost in objective historical conditions for their modes of codification, what we need is some cognitive basis for traditional categories of Vedānta and epistemic components for discourse processing and embodied representation of brahmajñāna.

Toward conceptualizing Upaniṣads as a verbal means of knowledge (śabda-pramāṇa), repetitive episodes in the Advaita sampradāya may be construed in some ways similar to Boyer’s (Reference Boyer1990) cognitive description of traditional discourse. Starting with ethnographic data among the Fang people of Gabon, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, Boyer distinguishes registers for discursive properties of evur, a term of ritual speech used among the Fang divinatory specialists. Without distinguishing different types of discourse about evur, Boyer explains, combined with the fact that participants with access to different registers in traditional discourse often have difficulty agreeing about what evur even really means, the common anthropological assumption that traditional categories should be treated as objects of shared definition (i.e., mutual knowledge) has usually settled on recognizing the semantic vacuity of “mystical terms” such as evur. Instead, Boyer describes the “full acquisition” of evur as corresponding to the acquisition of expert discourse. Extended as a general property for the reiteration of traditional events and expert utterances in traditional discourse, Boyer suggests, principled differences between the participants’ representations are a causal factor for repetition of the interaction, and this directs our attention toward relevant ways in which certain representations are not commonly shared by all participants (Reference Boyer1990, 21–36).

Consider the Fang genre of mvet, an oral tradition of epic storytelling where poets communicate important truths about ancestors. Becoming a specialized mvet storyteller is comparable to the status of a witch-doctor in the Fang tradition and involves arduous initiation rituals and extensive periods of apprenticeship under expert practitioners. Now, among participants involved in traditional events described as “mvet sessions” there are some competent listeners with more or less ritual knowledge. It is true that a good mvet session depends on interactions between the poet and listeners, but “if the events considered have any cognitive effects, it is because the representations available to different participants are different” (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 20). In episodes of mvet storytelling, cognitive effects depend on distributed knowledge and on the availability of different representations for the communicative event of mvet sessions. While mvet-related knowledge serves as a marker of identity, only initiated poets possess the special connection with ancestors that allows mastery of the domain of witchcraft. Event properties for the representation of terms in discourse registers that are precisely not shared as common knowledge and processes involved in the acquisition of traditional categories constitute “causal criteria” for the repetition of tradition. The heuristic value of Boyer’s hypotheses for expert utterances instantiated as speech-events is in distinguishing criteria of truth from conceptions of truth-terms, correspondences between a sentence and a described state of affairs, or the content or meaning of an utterance, in order to make explicit specific causal links for evaluating truth-statements in reference to the representations people have about episodes during which they are uttered.

Questions of origin, long preoccupying the history of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies, are of little importance when it comes to proving the truth of an utterance. Reproducing the circumstances of communicative events for singular utterances of Vedānta (vedānta-vākyas) is not dependent on causal criteria linking Upaniṣads to their medieval production among Yogins and devotees of Viṣṇu, for example. Nevertheless, as Parmentier points out, despite recognizing both the “linguistic division of labor” inherent to the use and representation of traditional categories and the “contextual nature of traditional memory,” important “semiotic regularities” are left unexplained in Boyer’s account of the formalization of language in traditional discourse (Reference Parmentier1993, 192). Limitations of Boyer’s work are made explicit when it comes to uncovering the pragmatic functions and semantic representation of Upaniṣads in the teaching tradition of Vedānta. The Sanskrit term sampradāya translates as “tradition” and in a brahmanical context the Advaita sampradāya includes diverse conceptual worlds of Indian religion, but I use the word in a technical sense to focus on the enunciation of truth-statements and discourse processing of traditional Vedānta. In a manner more akin to the sociological method of “sampling” than the intimate anthropologist and informant relationship of classical ethnography (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2000), data for the semantic production of traditional discourse of Vedānta has been derived from empirical observation of gurus, brahmans, and self-described traditional teachers of Advaita Vedānta at brahmanical institutions of Vedic learning (gurukulas) located throughout India. Many of those observed explicitly claimed to be participants in an uninterrupted teacher-student lineage (guru-śiṣya-paramparā) that extends to Dakṣiṇāmūrti, a depiction of the Vedic god Śiva as the primeval teacher of brahmajñāna in the form of one’s guru. Most were also male brahman renouncers (sannyāsins) affiliated with various regional teaching institutions (maṭhas) of Advaita Vedānta and have undergone ritual initiation (dīkṣā) into one of the ten monastic orders reputedly founded by Śaṅkarācārya (circa 750 CE), whose commentaries on the Upaniṣads are central to the Advaita sampradāya.

The sheer diversity of content consumed by the various forms of Upaniṣad has been suggested by Daya Krishna as “ample proof” that at least some “continued to be composed long after the Vedic corpus was finalized” (Reference Krishna1991, 96). For Krishna, what needs to be explained in light of this recognition is how, in fact, the Upaniṣads have nevertheless been accepted into the canon as Śruti, or “revealed authority.” Noting that the vast majority of Upaniṣads are accorded little importance by serious scholars of Vedānta, Krishna suggests “those that are so regarded are mostly not independent works at all, but selections from preexisting texts made on the basis of criteria which are neither clear nor uniform to our comprehension” (108). More specifically, Krishna calls for clearly formulated hermeneutical criteria, relevant to contemporary concerns, for circumscribing the corpus of Vedānta. While Krishna’s philosophical perspective clearly improves upon philological analysis of the term “Upaniṣad,” I would go even further and add that, for traditional discourse of Vedānta, causal criteria to explain how singular utterances of the great truth-statements (mahāvākyas), as well as subsidiary statements (avāntara-vākyas) of Upaniṣads which assist in comprehending the mahāvākyas, are used inductively in the process of acquiring and transmitting knowledge of brahman (brahmajñāna). There is also no clear or uniform reason to accept conflicting medieval typologies of “great” or “subsidiary” vedānta-vākyas. Ethnographic data for traditional Vedānta should be explained in reference to empirical studies in language comprehension and, most importantly, causal criteria must be grounded in cognitive hypothesis about the effects of genre knowledge of Upaniṣads and the reiteration of traditional categories in the Advaita sampradāya.

Experimental research suggests that text comprehension is influenced by reading goals and expectations associated with discourse genres. Genre expectations, moreover, effect the construction of “situation models” representing the state of affairs described in a text (Zwaan Reference Zwaan1994). While mental representations of stereotypical events (i.e., “scripts”) may also aid the construction of models of specific situations language comprehension tasks provide insight into the multi-modal processing of verbal input to form a coherent situational representation in long-term memory (Zwaan and Radvansky Reference Zwaan and Radvansky1998). Besides the situation model formed in conjunction with the semantic representation of the text or communicative event talked about, as Teun A. van Dijk (Reference van Dijk and Paul Gee2012) explains, language users construe pragmatic context models in order to adapt the goals, intentions, and knowledge base of their discourse to the communicative situation in which they are participating, and under the influence of which strategies of discourse processing, such as genre selection, may ensue. Developing a sociocognitive theory of context based on subjective participant constructs enabling discourse participants to interact in an epistemic community, van Dijk points out that context models are the ultimate goal of discourse comprehension. Simply put, “understanding ‘what is going on’ in communication and interaction is obviously more than just understanding the (semantic) meaning of discourse” (Reference van Dijk2006, 171). Defined in terms of context properties mediating between discourse and context, moreover, relevant communicative constraints of “context genres” facilitate control over variant discourses of a genre.Footnote 3

Discursive properties alone are insufficient for characterizing context-genres, that is, types of verbal activity, communicative event, or discourse. For instance, so-called Pure Vedānta and Yoga Upaniṣads probably share much of the same formal style, grammar, dialogical structure, and rhetorical devices as other genres in Vedic discourse, such as Āraṇyakas (forest treatises) or Smṛti (remembered) literature.Footnote 4 Contextual properties of Upaniṣads, however, may instead delimit variations of discourse with attention to the identities, relations, and roles of participants, the setting and type of activity or communicative event engaged in, and their cognitive basis. The specific combinations of speech-acts at the root of Vedic discourse suggests that “Upaniṣad” defines a class of genre with distinct discourse registers to account for “context-dependent language variation” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2008, 150–51). It is crucial to bear in mind that “genre expectations cause readers to allocate their processing resources in specific ways that meet the constraints of a given genre” (Zwaan Reference Zwaan1994, 930). Genre expectations relevant to the transmission of brahmajñāna should therefore anticipate discourse registers for the representation of traditional categories and the communicative intention to comprehend mahāvākyas while listening (śravaṇa). What we are aiming for is situational representation of truth-statements linked to singular speech-events in the Advaita sampradāya. The ways in which context models control the production and comprehension of discourse can be better understood following a brief introduction to the levels of representation in discourse processing.Footnote 5

Cognitive Models in Discourse Processing

In the sixth chapter of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, Uddālaka Āruṇi imparts knowledge of brahman (brahmajñāna) to Śvetaketu, uttering the Vedic truth-statement (mahāvākya) “you are that” (tat tvam asi) in repetitive episodes that validate the transmission of brahmajñāna when the Upaniṣad repeats: “He indeed understood that from him.”Footnote 6 Now, epistemic narratives usually involve several stages (e.g., ignorance, imagination, illusion, truth) in the process of knowledge acquisition, and “normally the construction [of the epistemic process] represented in the text is isomorphic to the one that takes the text itself as the starting point” (Todorov Reference Todorov and Porter1990, 47). Suppose, however, one character in a text is deictically referred to in different ways but with no recognition that various expressions indicate the same individual. With reference perpetually delayed, Todorov suggests “construction will no longer be possible … we have moved from the unknown or ill-known to the unknowable” (48). Nevertheless, empirical research on discourse processing demonstrates that, in addition to constructing a meaningful textual representation, successful comprehension also depends on readers being able to represent states of affairs referred to by the text.

We need to understand situations in which an individual is described in a text or communicative event and, as van Dijk and Kintsch explain, “the notion of coreference would make no sense in a cognitive processing theory of comprehension if we did not have this ability to coordinate the text representation with a situation model” (Reference van Dijk and Kintsch1983, 338–39). As experimental studies in psycholinguistics suggest, situation models help further explain the cognitive effects of domain-specific expertise and the ways in which people integrate verbal knowledge about a single topic obtained from different sources into a coherent situational representation (Zwaan and Radvansky Reference Zwaan and Radvansky1998). Cognitive situation models also provide the starting point for discourse production. Put another way, “depending on a number of constraints, language users, so to speak, ‘read off’ relevant propositions from their situation models, and thus construct the semantic representations, or ‘text base,’ that underlie a discourse” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, 66). The construction of a relevant propositional network constraining all levels of discourse representations (Kintsch Reference Kintsch1988) or “locally and globally coherent sequence of propositions” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987, 164), formed from the linguistic input and from the language user’s knowledge base, should not be confused with the surface structure or textual representation needed to form the situation model. Besides the referential situation indicated by the text or event talked about (i.e., the situation or event model) and semantic textbase representing the meaning of the discourse, as noted above, and in addition to the surface structure representation, which is mostly ignored at the textbase level, pragmatic context models also define communicative roles, intentions, goals, and relevant shared knowledge for discourse participants (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2008). Cognitive models construed in reference to knowledge of the world represent nonlinguistic variables in addition to the meanings of linguistic expressions.

Before abandoning surface properties of the Vedic truth-statement (mahāvākya) “tat tvam asi,” it should be noted that the words tat and tvam—each conveying their own meaning (śabdārtha)—display grammatical coordination and are rendered coreferential (sāmānādhikaraṇya) by the verb of being (asi). Following syntactic expectancy (ākāṅkṣā) and the contiguity of speech units (āsatti), coreferentiality of tat and tvam seems to make the meanings of the terms incompatible, and thus doubt leads to reasoning about their congruity (yogyatā).Footnote 7 The pronoun “you” (tvam) denotes Śvetaketu, but for philological reading of Upaniṣads it is exceedingly important to emphasize that “Uddālaka Āruṇi, who imparts some of the most influential teachings of ātman, never mentions brahman” (Black Reference Black2007, 31). In reference to the first person singular “I” (aham), the word ātman indicates oneself in the third person and is usually translated as “self,” or as Black eloquently puts it “the essence of life” (Reference Black2007, 36). More importantly, for Black, brahman appears to be semantically de trop, a concept open to being used in a general or eulogistic way for “bestowing a particular teaching with special significance” (32). In the teaching tradition (sampradāya) of Advaita Vedānta, Uddālaka codifies semantic and pragmatic properties revealing the identity of Śvetaketu and brahman, the meaning of the word “that” (tat-śabdārtha) in the Advaita sampradāya.Footnote 8

Philological literalism may not translate the word “that” (tat-śabda) to facilitate situational representation of speech-events in the Advaita sampradāya, but the equation of ātman and brahman has been equally disputed by the overwhelming majority of brahmanical theologians. For discourse comprehension of traditional Vedānta, it is all the more crucial to integrate surface structure and textbase representation with genre expectations for listening (śravaṇa). If utterances of Upaniṣads (vedānta-vākyas) appear indeterminate, listeners will not only possess a weak textbase representation but will also fail to construe situation models relevant to states of affairs revealed in the teaching tradition of Vedānta. Discourse processing of traditional Vedānta should therefore include strategies for the repetition of communicative events in the causal matrix of teacher-student lineages (guru-śiṣya-paramparās). Conceptualizing Upaniṣads as a verbal means of knowledge (śabda-pramāṇa), more specifically, requires efficient context models for handling truth-statements relevant to the reiteration of experiential categories in traditional discourse of Vedānta. One of the more important benefits of this approach lies in redirecting the focus away from how epistemic narratives of Vedānta are typically represented in worldviews, conceptual worlds, or cultural models of “Indian religion” (e.g., Vedism, Brahmanism, Hinduism, etc.).

Formulating cognitive hypotheses to account for truth and communication in episodes of traditional interaction, Boyer rightly discerns that compared to other situations in domains where specialists are supposed to possess some high degree of competence truth remains a “rare commodity,” and understanding why requires a more complex description of literalism. If there is any “literalism” involved in the repetition of tradition, Boyer explains, then it has to do with truth criteria being applied to utterances as “speech-events,” or events caused, rather than linguistic expressions instantiating “some abstract object (a sentence)”; and in such a case it is certainly true that “the number of situations in which it is necessary to find a true description or explanation of a state of affairs greatly outnumbers the number of contexts in which guaranteed truths are produced” (Reference Boyer1990, 92). Truth criteria cannot be applied to any “propositional content,” sentential meanings, or cultural conceptions supposedly preserved in truth-statements, as Boyer observes; the acquisition of traditional categories requires that some terms simply must be used in reliable registers to convey expert utterances, and “therefore the study of criteria is a question of ethnographic description, not anthropological theory” (57). In a call to anthropologists dealing with empirical data from different traditions, Boyer expresses the need for establishing a taxonomy of criteria of truth to account for the communication of “traditional truths” in traditional situations.

As illustrated in the following list, situation models represent the meaning of traditional events referred to as the cognitive basis for discourse production and processing of Vedānta:

-

1) Pragmatic context model

-

a) Context-genre Upaniṣad

-

b) Participants Guru (initiator), Śiṣya (initiate)

-

-

2) Semantic situation model

-

a) Event Upadeśa (initiation/instruction)

-

b) Setting Śravaṇa (listening)

-

In contrast, context models are subjective mental representations that define episodes of traditional interaction in which teachers and students participate. The collapse of situation models controlling the coherence of discourse and context models representing communicative situations, which form the basis for causally relevant speech-events in the Advaita sampradāya, such as when gurus deictically refer to the current communicative situation, calls for a distinction between personal knowledge and distributed cognition. In dialogues of Upaniṣads, students (śiṣyas) acquire knowledge of brahman (brahmajñāna) while listening (śravaṇa). The veracity of Vedic speech is often confirmed following specific teaching episodes when the method of instruction is connected to continuation of the teacher-student lineage (guru-śiṣya-paramparā). For instance, after the young Naciketas is taught by Death himself the Kaṭha Upaniṣad narrates: “Uttering and hearing this beginningless repetitive episode as taught by Death and received by Naciketas the wise man becomes exalted in the domain of brahman.”Footnote 9 Defining the communicative situation, therefore, is information included under the category upadeśa, a Sanskrit word that lends the dual sense of initiation and religious instruction, and which allows for a more precise distinction between traditional Vedānta and abstractions such as brahmanical “schools” of Advaita or religious movements centered on ritual initiation (or “dīkṣā”) and routinization of the Vedas. More specifically, for mental models construed in traditional discourse it is exposure to the Upaniṣads as a verbal means of knowledge in the Advaita sampradāya that constitutes initiation into the teaching tradition of Vedānta.

Consistent with van Dijk’s (Reference van Dijk and van Oostendorp1999) organization of mental model schemas to facilitate discourse processing among language users within a particular social domain (e.g., education), a social situation consists of communicative events in a spatiotemporal setting organized under certain circumstances.Footnote 10 Moreover, to define cognitive properties of mental models of the communicative situation, participant goals should be distinguished from communicative intentions. In traditional contexts for the transmission of brahmajñāna, students intend to listen to gurus for the purpose of attaining liberation (mokṣa). This is an important point, as it allows for a crucial distinction between mokṣa and the acquisition of brahmajñāna. Specifically, brahmajñāna is the means and mokṣa is the goal. While the categorical structure of context models influences situational representation of communicative events in the Advaita sampradāya, the contextual relevance of śabda-pramāṇa is that genre knowledge of Upaniṣads determines the inclusion of event model information necessary for initiating the teaching tradition of Vedānta, or transferring knowledge from teachers to students. Students seeking liberation (mumukṣus) therefore need to acquire context model schemas with situational categories relevant to the repetition of tradition. For instance, mumukṣus may very well be under the impression that mokṣa can be attained in any number of settings (e.g., reading Upaniṣads, meditating, performing Yogic postures, etc.) irrelevant to discourse processing and comprehension of traditional Vedānta. Initiation into the teaching tradition of Vedānta, on the other hand, is directly linked to participants’ representations of salient truth-statements (mahāvākyas) in traditional discourse.

In the case of “tat tvam asi,” causal criteria can be easily related to the referential basis for traditional discourse of Vedānta. Episodes of traditional interaction in the Advaita sampradāya warrant the application of truth-terms to a singular situation. Simply put, with general knowledge (sāmānya-jñāna) of their mere existence as limited individuals (jīvas), while believing themselves subject to death and rebirth (saṁsāra), students (śiṣyas) in the teaching tradition of Vedānta undertake an inquiry into the nature of reality (brahmajijñāsā) with an aim toward obtaining particular knowledge (viśeṣa-jñāna) of the ātman and immediate knowledge (aparokṣa-jñana) of brahman.Footnote 11 The result (phala) of brahmajñāna, directly acquired while listening (śravaṇa), in fact links the nonverbal meaning (avākyārtha) of truth-statements (mahāvākyas) to the desired situation: liberation while living (jīvanmukti).Footnote 12 Situational representation of embodied experience entails substantial modification of widely shared knowledge and routinized self-schemas represented in old “experience models” (EMs).Footnote 13 The discourse processed in analogy with the overall EM represents everyday embodied existence and, with the initiate now taking the role of initiator, is expressed in the noble style of first-person narration: “I am brahman” (ahaṁ brahmāsmi).Footnote 14

As taught to Śaunaka by Aṅgiras in the Muṇdaka Upaniṣad, knowledge of brahman may also be characterized as “higher knowledge” (pārā-vidyā) in relation to “lower knowledge” (pārā-vidyā) of the Vedas.Footnote 15 For ritual participants (yājñikas) in the habit of performing obligatory and occasional rites (nitya-naimittika-karma), the Vedas consist of injunctions (vidhi) and prohibitions (niṣedha) inculcating orthodox beliefs about certain acts and restraints in accordance with one’s duty (dharma).Footnote 16 In fact, the majority of brahmanical theologians involved in the routinization of the Vedas in the Advaita tradition do allocate some important role for the connections between knowledge and action (jñāna-karma-samuccaya).Footnote 17 Our specialized use of the term “tradition” (sampradāya) will therefore need to be rendered more complex with additional constraints, the foundation for which is listening (śravaṇa). Moreover, to mediate between pedagogical situations in the Advaita sampradāya and traditional discourse of Vedānta requires eliciting traditional categories and contextual properties of the Upaniṣads, but it is similarly important to understand the cognitive basis for contemporary representations of brahmajñāna.

Strategic Management of Common Knowledge

In van Dijk’s (Reference van Dijk and Paul Gee2012) framework for “epistemic analysis” of discourse, the management of different types of declarative knowledge (e.g., personal and social knowledge, specific and general knowledge, etc.) is controlled by context models that enable language users to participate in epistemic communities based on shared criteria of truth.Footnote 18 It should be emphasized that a mental model as presently conceived to aid discourse processing and comprehension is not a theory of cognition but rather a cognitive model of knowledge representation structured by previous autobiographical events which provide the referential basis for more general beliefs about particular events or stereotypical situations (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987). For a fully integrated cognitive theory of discourse processing and the use of mental models in knowledge acquisition, as van Dijk explains, “we need to know how they are related to other personal episodic information, such as personal experiences, opinions, knowledge about the Self, and socially shared knowledge and opinions” (Reference van Dijk and van Oostendorp1999, 142). Toward this end, van Dijk has formulated context models as a specific type of “experience model” (EM) especially designed for personal interaction in communicative events. EMs, context models, and situation or event models are all knowledge structures located in “episodic memory” and may be more generally referred to as episodic models.

For cognitive psychology, personal memories and knowledge about the world are generally distinguished in terms of episodic and semantic memory. As Boyer (Reference Boyer1990) points out, however, misguided claims about the “acquisition of culture” are often related to this distinction (42). The idea that “cultures” are transmitted as socially shared worldviews or commonly understood conceptual worlds is untenable in the light of empirical observation of the use and representation of traditional categories. A cognitive description of traditional Vedānta poses some challenge to anthropological theorizing and fieldwork practice based on what Greenfield (Reference Greenfield2000) describes as the “omniscient informant,” that is, the traditional anthropological assumption, extending back to Durkheim, that “culture is a homogeneous, unitary, and, possibly, superorganic whole” (568). Different members of a culture obviously have “different pieces” of knowledge, as Greenfield points out in reference to children in the ongoing process of being initiated into a culture, but the mutual knowledge hypothesis also faces problems in the context of traditional institutions. The classical ethnographic subject is called into question but not the importance of ethnographic research. On the other hand, if there were no common ground shared between participants in traditional interaction there would be no way to even conceive of communicative events, let alone truth, and hence the need for causal criteria, metalinguistic truth-statements, “institutionalized communicative resources,” and “indexical rules” for anchoring traditional categories to singular speech-events (Parmentier Reference Parmentier1993, 192).

While psychologists are not prone to studying such entities as “culture” or “tradition,” one irony is that recent theories about the links between episodic and semantic memory in cognitive anthropology continue to describe the representation of communicative events “as a one-way process, from semantic memory to the interpretation of singular occasions” (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 43). Providing a cognitive theory of the cultural transmission of verbal teachings in some doctrinal mode, Whitehouse “minimally presumes some level of commitment to schemas encoded in semantic memory—no more and no less” (Reference Whitehouse2004, 83 n. 13). For Whitehouse, sociopolitical modes of religious transmission in the “doctrinal mode of religiosity” lead to explicit verbal knowledge being stored in semantic memory and is distinguished from particular episodes in which it is acquired (69). When episodic knowledge is admitted in the doctrinal mode the resulting personal narratives are so stereotyped that Whitehouse suggests they simply dissolve into standardized and socially shared schemas of semantic memory. Moreover, in the general anthropological theory of cognition, along with the individual’s “absorption of a ready-made conceptual scheme,” it is assumed that people construct models by using social knowledge from semantic memory to interpret singular situations:

This certainly happens, although it seems strange that anthropology has not studied the opposite process, i.e., people using their memories of singular occasions inductively, to modify the semantic memory and build a representation of the world. The idea that people only make deductions form a “culture-given” conceptual scheme begs an essential anthropological problem—how people build certain representations of the world from fragments of experience—which in fact must be studied empirically. (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 43–44)

What is required is not only a more precise description of the relationship between social cognition and personal knowledge but also a better understanding of the role of verbal knowledge in episodic situations. For the classic definition of episodic memory, Tulving distinguished autobiographical reference from cognitive reference of semantic memory. As Tulving explains, “an integral part of the representation of a remembered experience in episodic memory is its reference to the rememberer’s knowledge of his personal identity” (Reference Tulving, Tulving and Donaldson1972, 389). Information stored in the semantic memory, on the other hand, refers to existing cognitive structures that represent previously learned knowledge and which can be used to update or modify the contents of episodic memory through processes of retrieval such as inference, generalization, deduction, or the application of rules. The retrieval of information from episodic memory similarly changes the contents of the episodic memory store and has the additional function of making the contents available for inspection. New input based on autobiographical events, of course, is stored in reference to knowledge of one’s personal identity. The construction of event models may also mirror the structure of EMs due to the primacy of personal experiences and the ways in which communicative events are embedded in our daily lives (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and van Oostendorp1999). Before linking strategies of discourse processing to preferred structures of discourse, which influence the construction of episodic models, however, we need to consider processes in the movement from occasion-bound utterances and speech-events to the representation of general propositions and stereotypical situations.

At the same time, going beyond common discourse requires mentioning an important property of traditional categories. There are principled differences in the way traditional categories are used and represented in common and specialist registers of discourse, as made explicit in terms of cognitive salience. While expert discourse of evur is expressed as definite truth-statements, for example, common discourse is generally vague, abstract, and conjectured, such as “that is what the witch-doctors say,” or “the ancestors knew all about evur,” and is therefore not very salient (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 30–34). More importantly, the acquisition of expert discourse differs significantly from common knowledge based on stereotypical representations of evur. While traditional categories and natural kinds are both acquired through ostensive presentations, Boyer notes a simple distinction in the acquisition of natural kind terms acquired by singular presentations of exemplars of the kind, which are then used to construct a common stereotype, and the achievement of expertise. With the series of ostensions forming the basis for acquiring natural kind terms a mental representation more or less converges toward the common stereotype, but “the full acquisition of evur, on the other hand, starts from the stereotype and gradually diverges toward a series of memories of personal experiences” (39). The acquisition of expert discourse is a result of episodic knowledge based on rites of initiation and ritual contact with the domain of evur so it is hardly surprising that expert use of evur is inconsistent with gossip and common discourse. In fact, since the domain of evur is limited to initiates, as Boyer points out common knowledge about evur is not based on building a stereotype out of ostensive presentations of evur in the first place.

Important strategies of discourse processing can be better explained in reference to van Dijk’s work on “ethnic encounters” and the role of episodic models in the perception, representation, and discourse expression of socially shared evaluative beliefs (i.e., opinions) about ethnic minorities. The memory organization of ethnic situation models is hypothesized as a schema consisting of fundamental categories, such as setting, participants, and events, as well as subjective evaluations arranged in hierarchical structures of propositions. The activation and retrieval of preferred linguistic input under “top-down control” of contextually relevant topics in prejudiced discourse serves to provide “the macroproposition that guides semantic production” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, 67). To understand the sociocognitive mechanisms that underlie prejudiced-representation of ethnic encounters van Dijk details the ways in which ethnic situation models provide the experiential basis for socially relevant ideological frameworks and scripts linked to general ethnic attitudes shared by dominant members of society. Prejudice is conceived not simply as individual beliefs but as adapted instantiations of social attitudes in episodic models. As the interface between ethnic situations and knowledge of ethnic minorities, ethnic models provide the cognitive representation and referential basis for the production and comprehension of prejudiced discourse. Discourse topics are arranged in a categorical “superstructure” and “the presence, absence, or order of specific categories may well be significant and influence the structures of models and hence social representations” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Crowley and Mitchell1993, 119). The lack of certain topics, moreover, may produce partial models and impaired knowledge.

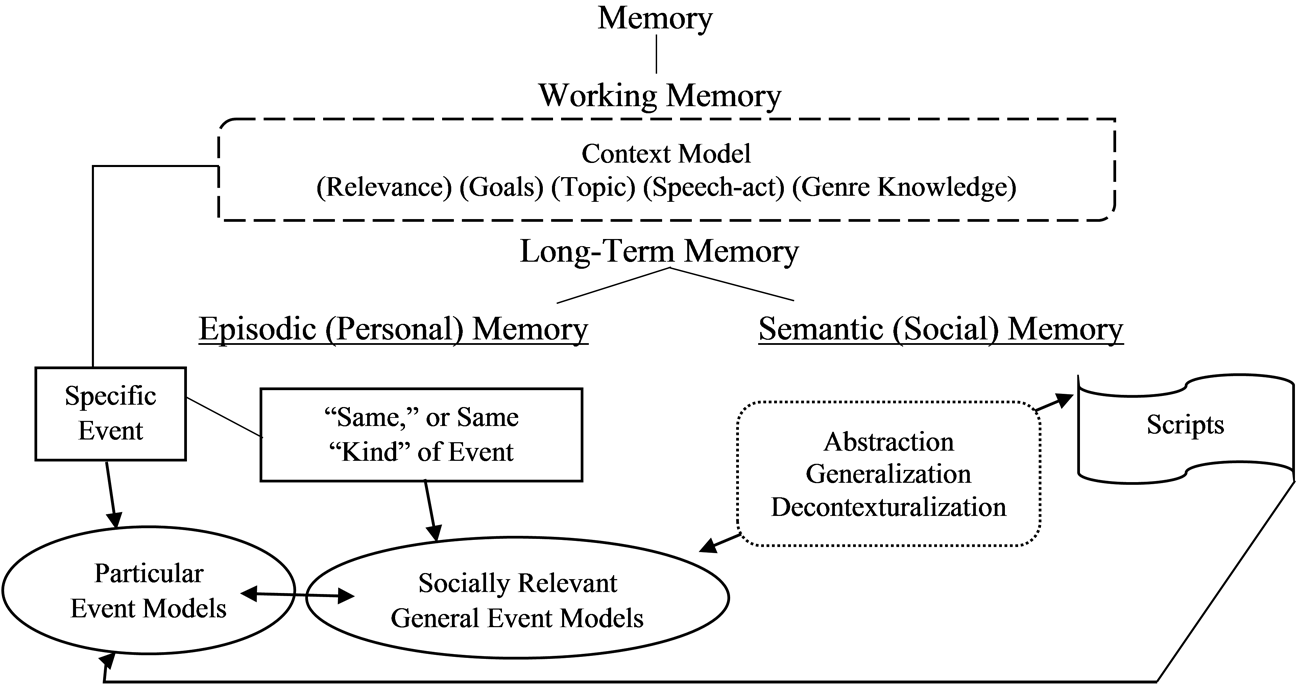

The need to understand cognitive processes involved in knowledge acquisition and construal of repetitive stereotypical episodes featuring prototypical actors in familiar situations calls for a distinction between particular and general event models as depicted in figure 1. In addition to information obtained from the particular communicative event in which we are currently participating, situation models are constructed from fragments of general models based on stereotypical events and instantiated common knowledge stored in the semantic memory. The main purpose of the particular model is in fact to update the general models we already have about relevant communicative events (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987). General models should not be confused with common knowledge represented in social frames and scripts. While socially shared beliefs may help structure general models, van Dijk points out, script information is only instantiated in personal models in terms of our understanding of discourse (as controlled by our context model). Episodic models representing private beliefs form the experiential basis for decontextualized scripts, via the instantiation of socially shared attitude schemas characterized by fundamental categories relevant to a dominant group’s management of knowledge about ethnic minorities (e.g., the origin of an ethnic group, appearance of ethnic group members, the role of ethnic minorities in society; van Dijk Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, 71).

Figure 1. Referential basis for discourse processing (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987, Reference van Dijk, Crowley and Mitchell1993)

It is possible to link strategies of discourse processing to context constraints in episodes of traditional interaction. Given the specific type of speech-events necessary for the acquisition of expertise, Boyer explains that “people must build semantic memory data from the limited material presented in a series of singular situations … therefore the processes through which episodic memories are used to generate knowledge are crucially important to anthropology” (Reference Boyer1990, 43). The importance of singular situations raises the issue of limited access to registers in traditional discourse. In the absence of traditional speech-events social cognition amounts to vague statements in common discourse. While common knowledge is general and inconclusive, on the other hand, gossip is definite, centered on singular situations, and “it is always assumed that the speaker has a definite interest in transmitting a certain version of events” (31). Nevertheless, both general and particular common statements about evur, whether rumors about a very definite event or abstracted as common or contradictory scripts representing stereotypical situations, lack the causal criteria necessary for producing expert utterances. For discourse recipients, episodic representation of gossip about evur will involve context properties such as who told them about which witch-doctor performing a certain ritual, when, and in what setting (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987). Gossip about witchcraft or any other communicative event may be rejected outright, if recognized as such, but it is still important not to dismiss the credibility and strategic management of common knowledge.

Consider the way macropropositions fill schematic categories in storytelling about ethnic minorities. Drawing on empirical data van Dijk found that when people talk about ethnic events negative opinions in the hierarchy of a situation model were remembered more frequently and, moreover, “the strategies involved in ethnic model building by prejudiced social members are geared toward such a negative organization of situation models in memory” (Reference van Dijk and Forgas1985, 72). Stories generally consist of a complication, resolution, and evaluation, but in storytelling about ethnic encounters the resolution is usually absent (i.e., complications related to ethnic minorities are largely unresolved), and for ethnic situations relevant to a dominant group “the Evaluation and Conclusion categories will guarantee not only that the events are portrayed as they see them, but also that they are evaluated according to shared and accepted norms” (73). Such stories, defined by van Dijk as discourse expressions of event models, reveal salient topics in prejudiced discourse (e.g., crime, deviance, harassment, strange habits, etc.). As the cognitive interface between personal experiences and social events, scripts in semantic memory are not only drawn from repeatedly shared models but are also “used to understand new episodes through (partial) instantiations in models of such episodes” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Crowley and Mitchell1993, 111). Socially shared scripts therefore serve as top-down constraints to facilitate comprehension of preferred ethnic models. At the global level of semantic representation topics are subject to modification under text and context constraints of the communicative situation, but the lack of actual experience with ethnic minorities reveals the strategic management of ethnic prejudice. In this process, “the lack of concrete personal experiences, such as encounters with minority group members, will urge people to ‘imagine’ such experiences by constructing models ‘by default,’ i.e., by instantiating preestablished ethnic attitude schemata from semantic (social, shared) memory” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987, 190–91). Ethnic attitudes are thereby inferred from other socially shared prejudices informed by relevant scripts of a knowledge community.

The management of shared knowledge, prejudice, and discrimination is not primarily based on direct contact or observations of ethnic minorities but is often derived from discourse produced by the “symbolic elites,” a disparate group of media relations depending on scholarly discourses about ethnic affairs (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Crowley and Mitchell1993, 113). In the case of prejudiced discourse, topics controlled by biased journalists manipulate the way readers understand the ethnic situation. The upgrading or downgrading of stereotypical topics in repeatedly used general models, while conducive to preferred representations of ethnic events, at the same time “leads to less well-established and less complete models, which in turn may impair more neutral knowledge and belief formation about minorities” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Crowley and Mitchell1993, 118). The reproduction of ethnic prejudice depends on the construction and standardization of biased models of ethnic encounters and “stereotypical stories” validated by the symbolic elites. Discourse structures of news discourse represent biased scripts that “manipulate model-building” and aid the construction of partial, imbalanced, preferred mental models with discourse topics that define relevant information about ethnic encounters (123).

If context models are used to understand particular communicative events then it is especially important to note that “not only the type of communicative event but also our actual goals and interests may as such—that is, without having yet read or heard the discourse—be used to activate or retrieve particular situation models” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987, 180). Moreover, recognition tests have shown that a more general event model may interfere with the comprehension of propositions describing apparently similar situations (Garnham Reference Garnham1981). The precise combinations of models and scripts needs to be monitored by a control system that allows strategic updating of personal knowledge. One problem with the construction of biased models is that incoming information from credible sources is then more difficult to evaluate from a neutral perspective if at odds with what we already know about a genre of discourse or communicative event. Strategic model use suggests that a particular model is built from old models and new information, but “only in some cases may it be necessary to completely transform a previous model in such an updating process, e.g., when we see that we previously had completely misunderstood similar situations” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Horowitz and Samuels1987, 181). Common knowledge and stereotypical scripts seem to sustain situation models cued by salient topics repeatedly announced in discourse. Knowledge acquired during communicative events in a social domain (e.g., education) is used to update personal knowledge about the domain (e.g, setting, participant categories, communicative intentions), but more important is that manipulating situational representation of Vedic truth-statements are contextual constraints of colonial models and not genre constraints of Vedānta.

Imperial Encounters in Colonial Discourse

In collected works published posthumously in 1799 Sir William Jones recalled the challenges of obtaining reliable extracts of the Vedas among other specious manuscripts in India. During the seventeenth century Dara Shukoh had spent some time with Vedic scholars compiling and translating a number of Upaniṣads into Persian, but Jones found this work to be “barbarously written” and quite “deformed” by spurious additions and commentaries (Jones Reference Jones1799b, 415). After a long cultural and commercial barrier between India and Europe British indologists stationed in West Bengal were finally able to reject Islamic sources mediating access to the Vedic tradition and focus instead on providing direct English translations of the Sanskrit originals.Footnote 19 At the end of the seventeenth century Europeans were still left with speculative Greek fragments about inhabitants of the subcontinent and Mosaic ethnology derived from the bible (Marshall and Williams Reference Marshall and Williams1982; Halbfass Reference Halbfass1988). As late as the eighteenth century the world’s people continued to be widely classified as Jews, Christians, Muslims, or heathens (von Stietencron Reference von Stietencron and Sontheimer1989; Masuzawa Reference Masuzawa2005). Knowledge of Indian heathens increased significantly when trajectories of Orientalist discourse, secularization, and comparative philology all joined in the historic moment described by Edward Said as “the final rejection of the divine origins of language … a secular event that displaced a religious conception of how God delivered language to man in Eden.”Footnote 20 It would be difficult to overestimate the significance of the discovery of language.

Philology has been described as the study of “national culture” preserved in the linguistic history of nations (Bloomfield Reference Bloomfield1914, 319). When Jones delivered the ninth-anniversary discourse on the Origins and Families of Nations to the Asiatick Society in 1792, he was indeed repeating a familiar story of Mosaic ethnology with new vigor.Footnote 21 Along with classifying the world’s languages into families, however, the “discourse of philology” ultimately reconfigures the idea of “primal language given by the Godhead to man in Eden.”Footnote 22 In the same speech widely regarded as initiating the science of comparative philology in 1786 Jones already expressed the belief that Pythagoras and Plato derived “sublime theories” from the “same fountain” that inspired seers of Vedānta (Jones Reference Jones1799a, 28). Later indologists even looked to the Vedas for the origins of religion (Inden [Reference Inden1990] Reference Inden2000, 98). Concomitant with translation of the Vedas, however, was the suspicion that any revealed knowledge had been lost (or perhaps preserved at the cost of “many modifications”) and that the origins of “Brahmanism,” or later “Hinduism,” lie elsewhere, particularly in indigenous remnants of the pre-Aryan past and imaginative practices stemming from post-Vedic civilization (Renou Reference Renou1961).

Although long aware of teaching traditions surrounding the Upaniṣads, indologists continue to conceptualize Vedānta as a doctrinal system comparable to western schools of philosophy. Delineating “hegemonic texts” in the field of indology, Inden traces the distinction between speculative philosophy of “Brahmanism” and superstitious cults to H. H. Wilson’s account of “sects” (i.e., “six schools”) in the “Hindu system” ([Reference Inden1990] Reference Greenfield2000, 97). Already during the eighteenth century the Orientalist Alexander Dow characterized Indian superstitions as brahmanical inventions. In his study of the “Hindoos” Dow claims that two distinct systems of worship arise in India. Learned Brahmins who look through the medium of “revelation” and “philosophy” recognize the existence of one “supreme being” but for the masses incapable of contemplating the infinite, formless, and immaterial reality priests invented all sorts of allegories and symbols. While enquiry into the human mind and natural reason has rid superstitious absurdities from many nations, Dow doubts common sense “ever involved any nation in gross idolatry, as many ignorant zealots have pretended” (Reference Dow and Marshall1970, 139). Rather, Brahmins are accused of abetting an idolatrous system of their own making.

Orientalist representations of the Upaniṣads rely just as much on linguistic input of collated manuscripts as strategic classification systems based on growing knowledge of Indian religion. The single most important point in Sir Monier Monier-Williams’ attempt to distinguish “Brahmanism” from “Hinduism” is that, in passing, he provides one of the more prevalent Orientalist hypothesis for the origins of Vedānta. For Monier-Williams, the Vedas display physiolatry, polytheism, animism, and the lowest types of fetishism. Vedānta, on the other hand, is the “unaided intuitions” of Indian rationalists and freethinkers. In contrast to the vast majority of Hindus, that is, “besides the great demon-worshipping, idolatrous, and superstitious majority, another class of the Indian community must also be taken into account—the class of rationalists and freethinkers” (Monier-Williams Reference Monier-Williams1889, 5). Earnestly contemplating questions such as “who am I?” but with little success, nevertheless, “it was in the effort to solve such insoluble enigmas by their own unaided intuitions and in a manner not too subversive of traditional dogma, that the systems of philosophy founded on the Upanishads originated” (6). It is precisely this description that is repeated with little alteration in subsequent hypotheses for the origins of the Vedas.Footnote 23

During the late eighteenth century Indo-European philology appeared to debunk the Adamic myth of sacred language and, as a result, “language became less of a continuity between an outside power and the human speaker than an internal field created and accomplished by language users among themselves” (Said [Reference Said1978] Reference Said1994, 136). In the study of the Vedas, however, the social institution of speech has attracted little attention from indologists. The urge to use Upaniṣads as the basis for some elaborate philosophy has also led to novel situation models of Vedānta. In rejecting discursive properties of Upaniṣads as extravagant symbolism or figurative language Paul Deussen fails to comprehend contextual features of traditional interaction, but this failure is symptomatic of another recurrent theme in Orientalist representations of Vedānta. The “philosophical simplicity” of Upaniṣads coincides with a general consensus about how simple ideas of Vedānta are acquired. In our quest to unlock the mysteries of nature, Deussen explains, “the key can only be found where alone the secret of nature lies open to us from within,” and indeed it was through plunging inward to their “innermost self” that philosophers recorded in the Upaniṣads first intuited the truth of brahman ([Reference Deussen and Geden1906] Reference Deussen and Geden1979, 39–40). In the “psychology of Vedānta” brahman is the “cosmic principle” and ātman is the “psychic principle,” and their equation represents the fundamental philosophy of the Upaniṣads, a proper understanding of which will purportedly benefit the entire human race.

Conjuring ad hoc hypotheses for the acquisition of brahmajñāna leads to imaginative instantiations of Vedānta. For Deussen, Upaniṣads record the “rich mental life” of individual philosophers contemplating philosophical doctrines but perhaps further developed in the course of public discussions, and “the oldest Upaniṣads preserved to us are to be regarded as the final result of this mental process” ([Reference Deussen and Geden1906] Reference Deussen and Geden1979, 22). Summarizing Advaita Vedānta according to Śaṅkara as the “path of knowledge,” Deussen elsewhere explains that salvation is nothing other than knowledge of the individual soul’s identity with brahman and this can be known neither through performing good works nor through moral purification. The ātman, as the “knowing subject,” cannot be placed before us and known as an object and “even searching in the Scripture is not enough to attain this knowledge but merely serves to remove obstacles” (Deussen Reference Deussen and Woods1906b, 40). In the “lower knowledge,” Deussen suggests, the ātman is opposed to our own self and worshiped as a personal deity but “in the higher knowledge, since the ātman is in reality not an object, the cause of its knowledge is not further explicable” (41). Having already admitted the limitations of actions in regard to the acquisition of brahmajñāna, Deussen nevertheless proceeds to acknowledge a number of “religious practices” as the means (sādhana) for acquiring liberating knowledge of the ātman. Though it may seem inexplicable in light of his earlier comments, for Deussen knowledge can somehow be attained after all by performing the requisite ethical works and meditating (e.g., “pious meditation,” “contemplation,” “concentration,” “sitting meditation,” etc.).

Once the divine status of Hebrew is empirically discredited, revelatory authority is relegated to the internal field of freethinking individuals. The significance of this event is comparable to the transformation of church-world relations in Europe and elsewhere during previous centuries. Orientalist discourse of Vedānta has also significantly influenced Hindu understanding of the mahāvākyas.Footnote 24 The relatively high esteem that nineteenth-century indologists held for Vedānta had the effect of empowering anticolonial resistance after loosening brahmanical control of the Upaniṣads, in the course of which the role of speech-events in Vedic discourse was reconceptualized. In the Hindu nationalist Swami Vivekananda’s vision, “spiritual revelations” of the Vedas are merely records of profound experiences. The Upaniṣads provide a collection of “spiritual laws” theorizing the relations between individual spirits and the “Father of all spirits” but these laws exist within every individual and must be personally realized in “superconscious” experience, not faithfully accepted as secondhand reports of Vedic ṛṣis (seers) (Rambachan Reference Rambachan1994, 43–49). From concrete situations of British India arise similar widely construed colonial models of Vedānta.

Crossing the Great Divide

In acknowledging relevant constraints of the colonial situation the claim that contextual properties of imperial encounters controlling the production and comprehension of discourse instantiate novel typologies of knowledge would hardly need justification. After all, as unique participant constructs defining the communicative situation, context models in an empirically significant sociocognitive theory of context are specifically designed to help “explain the nature of the relations between society and discourse, for instance, why different people in the same social situation may still talk differently” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2008, 23). As such, context models can neither be reduced to discursive genres mediating between discourse and context nor determined by objective social conditions. With Upaniṣads conceptualized as context-genres what needs to be explained is the role of Vedic truth-statements (mahāvākya) in the management of knowledge and the influence of context-relevant participant categories in context model schemas constraining preferred discourse structures of Vedānta.

For a schema of context-dependent discourse processing conditioned by imperial encounters particularly relevant is the way Deussen defines the acquisition of brahmajñāna according to Śaṅkara. Knowledge is the means and emancipation is the goal, which is attained through knowledge of the ātman, Deussen explains, but as already noted the identity of ātman and brahman betrays a philosophical simplicity. Therefore, after hearing about brahmajñāna, there is more work to be done if one is to really attain the goal. Especially revealing is Deussen’s promotion of “pious meditation,” which “consists in devout contemplation of words of Scripture, for example, tat tvam asi, and, like the process of threshing, is to be repeated until knowledge appears as its fruit” (Reference Deussen and Woods1906b, 42). What Deussen is saying, in other words, is that knowledge obtained from the utterance “tat tvam asi” is only indirect, theoretical, and conceptual, but through performing other actions such as worship (upāsana) or repeated meditation (prasaṅkhyāna) the indirect knowledge (parokṣa-jñāna) can then be transformed into liberating, immediate knowledge (aparokṣa-jñāna).

If we need a model of traditional authority, then the work of Śaṅkara is no doubt where to find it. We are not only assured he is India’s greatest philosopher, but “European scholars have, consequently, attempted to portray Śaṅkara as the icon of the ideal Brahman, a man who is simultaneously swimming with and against the tide of Indology’s history” (Inden [Reference Inden1990] Reference Greenfield2000, 106). What is reproduced in such caricatures of Śaṅkara, however, are many of the same presuppositions and assumptions underlying “Great Divide” models of the differences between “tradition” and “modernity.” Understood in terms of distributed cognition and causal criteria for the veracity of truth-statements there is no corresponding divide between speech-events of the Advaita sampradāya and traditional discourse in secular modernity, but as Boyer correctly suggests at the center of Great Divide conceptions is an unbalanced focus on the so-called demise of tradition.Footnote 25 Similarly, the birth of the modern too often entails generalities about late capitalist societies and contemporary ways of thinking. In most cases, entertaining the Great Divide betrays a thoroughly top-down approach to traditional worldviews and symbolic systems of modernity.

One common feature of indological models of “traditional” and “modern” Vedānta involves Christian missionary influence on social reform movements in India. Much has also been made of the rise of the Indian middle class and open access to both English and regional translations of the Vedas. Similar issues have been emphasized by social anthropologists without regard to modes of traditional interaction (Fuller and Harriss Reference Fuller, Harriss, Assayag and Fuller2006). As van der Veer suggests, secularization in India facilitates “a kind of Protestant reformation in Indian religion that entails a ‘laicization’ of organization and leadership” (van der Veer Reference van der Veer1994, xiii). The participation of bourgeois Hindus in transmission of the Vedas demonstrates that modernization is not simply a universal process initiating the decline of religion. Lamenting the fact that most people who learn the Veda by rote, chanting in Sanskrit, do not attempt to understand its meaning, Murty admits that in earlier times only men of the “three upper castes” (traivarṇika) have been allowed to hear the Vedas and further explains that “even today most Brāhmins who have learnt the Veda, either with or without meaning generally do not teach it to women, śūdras, and others” (Reference Murty1993, 14). In the context of “imperial modernity” (van der Veer Reference van der Veer2014), however, Hindu nationalists such as Vivekananda and other swamis educated in Christian missionary institutions and who may not have had access to the Vedas in previous centuries are seen to take the lead in spreading Upaniṣads on the subcontinent and abroad.Footnote 26

The remarkable thing about the laicization of Advaita Vedānta is the extent to which discourses of modernity have influenced the teachings of “orthodox” centers of Vedic learning (maṭhas), such as those supposedly founded by Śaṅkara in the eighth century. Scholarship in this area has focused on distinctions between social practices in traditional and modern Indian society or the adoption of Western categories of thought (e.g., philosophy, religion, spirituality, etc.) by contemporary teachers of Vedānta (Fort Reference Fort1998, 152–71; van der Veer Reference van der Veer1994, 130–37). When understood as a particular form of interaction involving the distribution of roles, truth criteria to evaluate utterances, and distinct registers of discourse to represent traditional categories, traditional speech-events are just as liable to be found in prototypical “modern” contexts (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 114). Imperial encounters, on the other hand, provide a starting point for the production of discourses that link colonial scripts to Orientalist representations of Vedānta. The propositional network in colonial discourse based on situational representation of Upaniṣads, moreover, significantly alters genre expectations for communicative events of Vedānta through ongoing processes of abstraction and decontextualization.

We need to clarify more precisely the contextual constraints to account for relevant properties of cognitive models in discourse of Vedānta. As van Dijk notes, “as we do with discourse, so we can classify contexts as different types, and these types are often related to different discourse genres” (Reference van Dijk2008, 21). Classifying different types of discourse necessarily involves specific criteria to account for discourse variation. In this regard we must consider genre knowledge and the role of speech-acts constituting different styles of using context-genres. For sociocognitive model theory, whether dealing with variant discourses of different genres or different registers for the same discourse genre, it is crucial to recognize what remains the same and therefore provides the basis for variation. Semantic variation for discourses sharing the same macroproposition, in particular, needs some referential basis to account for contextual properties of communicative events. Variation is relative to situational differences, context models, and levels of representation, such that “discourses are variants (at some level) if they share the same event model (at some level), but if their context models are different” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk2008, 140). Given the contextual constraints on language and differences of style and register in the use of a genre, a context-relevant definition of discourse variation should also be extended to speech-acts and communicative events for “‘recontextualization’ of the ‘same utterance’” (141–42). To avoid opening a long digression about genre constraints and cultural relevance, at this point we can only admit concern for the surface structure representation of hierarchical topics in cognitive models underlying discourse of Vedānta.

Brahmanical exegesis of particular sentences of the Upaniṣads classified as “great statements” (mahāvākyas) defines the canonical order of macropropositions in Vedic discourse that have subsequently been a main focus of Orientalist discourse. Of different ways brahmanical theologians have interpreted “tat tvam asi” it is true that the nondual (advaita) tradition of Vedānta has held the most fascination for philosophical idealists. Despite the immense influence of Śaṅkara and the substantial reinterpretation of his commentaries on the Upaniṣads by transnational Hindus, indologists from Deussen onward have also provided an impartial account of Advaita Vedānta. One of the first Orientalists to express serious interest in Śaṅkara, Deussen suggests that after hearing the statement “tat tvam asi” further mental acts such as upāsana, which he translates as the repetition of “pious meditation” on the mahāvākya, are necessary for acquiring direct knowledge of brahman.Footnote 27 Given the central role of the mahāvākya in the acquisition of brahmajñāna it seems odd to fall back on Yogic practices to comprehend the Upaniṣads. Nevertheless, Deussen’s portrayal of Śaṅkara is not entirely unwarranted and deserves further consideration in the light of contextual constraints and social scripts instantiating tat tvam asi.

It is particularly noteworthy that popularization of Śaṅkara’s work in the tenth century was largely due to the dominance of theologians such as Vācaspati Miśra (circa 850–970 CE), who sought to harmonize his commentaries with criteria established by Maṇḍana Miśra’s (circa 660–720 CE) Advaita treatise the Brahmasiddhi.Footnote 28 During the earliest period following Śaṅkara and his immediate disciples both supporters and opponents of Advaita Vedānta take Maṇḍana as the “Advaita proto-type” (Sastri [Reference Sastri and Sastri1937] Reference Sastri and Sastri1984, vi–vii). Regardless of whether Maṇḍana explicitly advocated the doctrine of repeated meditation (prasaṅkhyānavāda), which must be located in broader debates about the combinations of knowledge and action (jñāna-karma-samuccaya), or if Vācaspati is more responsible for adopting this Yogic practice into the Vedānta tradition, as Sengaku Mayeda correctly suggests, Maṇḍana does hold the same idea in what he calls “upāsana” (Reference Mayeda1992, 197 n. 13). In more general terms, the causal relation between Śruti and the acquisition of brahmajñāna for Śaṅkara can be distinguished from epistemic communities traced to Maṇḍana and subsequently popularized by Vācaspati and the so-called Bhāmatī School of Advaita Vedānta.Footnote 29 For Maṇḍana, verbal knowledge (śabda-jñāna) obtained from the Śruti is indirect (parokṣa) (Maṇḍanamiśra [Reference Maṇḍanamiśra and Sastri1937] Reference Maṇḍanamiśra and Sastri1984, 134). Verbal knowledge depends on an understanding of individual word meanings along with syntactic relations and is thus conceptual and relational (samsṛṣṭa-viṣaya). Therefore, after hearing the Śruti, some other repetitive procedures are required to gain direct knowledge (aparokṣa-jñāna) of nondual reality (brahman).

In contrast to Maṇḍana, Śaṅkara sought to establish proper enquiry of the Śruti for conveying the nonrelational sense (akhaṇḍārtha) of the mahāvākyas.Footnote 30 Despite Śaṅkara’s dissociation from the “inherently dualistic and saṁsāric activities” of Yoga practices and “mental acts,” as Halbfass explains in regard to repeated meditation (prasaṅkhyāna), “it appears that this method was adopted and perhaps reinterpreted by certain Vedāntins who employed it as a technique to realize the meaning of the Upaniṣadic ‘great sayings’ (mahāvākyas)” (Halbfass Reference Halbfass1991, 227). While Śaṅkara’s immediate disciples also strongly refuted any combination of knowledge and action (jñāna-karma-samuccaya), later theologians interested in “harmonizing” Vedic schools disregarded the traditional teaching methodology of Vedānta (Comans Reference Comans2000). In traditional discourse of Vedānta, immediate knowledge is directly attained while listening and there is no need for dualistic practices nor the acquisition of further procedural knowledge when the meanings of the words of Upaniṣads are correctly understood. As Śaṅkara’s disciple Sureśvara suggests, moreover, the nonverbal import (avākyārtha) of tat tvam asi is not expressed in the propositional form of any sentence.Footnote 31

For discourse processing and comprehension of traditional Vedānta it is crucial not to confuse truth statements of Upaniṣads with amodal propositions denoting categories represented in the mind as verbal definitions (lakṣaṇa) or sentential meaning (vākyārtha). As Kocmarek explains, although “the task of man” is to find out the meaning of the Vedic truth statements, “clearly the meaning of such revealed language cannot be taken to lie merely in its content … since that to which the mahāvākya-s point (namely, Brahman) is totally unobjectifiable” (Reference Kocmarek1985, ix). For Kocmarek, it would be fruitless to attribute the self-certifying meaning of “revealed language” to social rules employed by language users in episodes of human interaction. Quoting Upaniṣads to characterize the “meaning,” or truth, of Vedic language (vaidikā-vāk) in terms of its utility, that is, to the extent that it “works,” Kocmarek’s suggestion that one who knows brahman becomes brahman parallels attempts in the Advaita tradition to explain the nonverbal meaning or nonrelational sense conveyed by the mahāvākyas. While scholarship on Advaita has pointed to the importance of the guru-śiṣya-paramparā for the transmission of brahmajñāna (Cenkner Reference Cenkner1983; Rambachan Reference Rambachan1991; Comans Reference Comans2000), there has been no cognitive description to account for discourse comprehension and knowledge acquisition in traditional Vedānta.

The crucial hypothesis for criteria of truth is that utterances considered true are those which represent a causal link between the utterance and the described state of affairs, and “if such criteria are taken into account, the only reliable utterances are those for which a relevant causal description is available” (Boyer Reference Boyer1990, 92). As Boyer points out, this is precisely what makes truth such a rare commodity. One implication of traditional discourse is that the acquisition of brahman is constrained by communicative events of the Advaita sampradāya. It is neither the Sanskrit term derived from √bṛh, meaning “to expand,” nor its English definitions (e.g., “the ultimate Reality,” “Absolute,” “great,” “greater than the greatest,” “the Absolutely Great,” “the Divine,” etc.) that delimit the reference of brahman (Grimes Reference Grimes1996, 96). Truth criteria are not only applied to statements uttered in particular situations, and not all utterances of gurus are considered truth statements. The criterion of truth is that mahāvākyas are represented in such a way that the acquisition of brahmajñāna is directly linked to listening (śravaṇa), and the production of true utterances is precisely determined at the local level of discourse variation. In common discourse of Vedānta, the mahāvākyas cannot produce liberating knowledge.Footnote 32 Through ongoing processes of abstraction, generalization, and decontextualization, moreover, the Upaniṣads are totally removed from the teaching tradition and recontextualized with stereotypical scripts aided by routinized rituals. The fact that Uddālaka Āruṇi declares “you are that” (i.e., not “you will become that”) calls into question the relation of situation models construed by Yogins proffering the Upaniṣads and communicative events in the Advaita sampradāya.

Conclusion

In this article I have argued the importance of conceptualizing Upaniṣads as context-genres to account for contextual effects of genre knowledge and strategies of discourse processing. For a sociocognitive theory of context, “contextual knowledge about the type of communicative event or genre … tells the participants what specific communicative functions these genres have and what event model information is or should be most relevant to accomplish that function” (van Dijk Reference van Dijk and van Oostendorp1999, 134). Colonial scripts, moreover, facilitate the construction of preferred models with strategic processes that reconfigure genre expectations for the management of common knowledge about communicative events in the teaching tradition of Vedānta. While I have pointed to early dominant movements in the Advaita tradition that seem to have overlooked important pedagogical methods (prakriyās) of Upaniṣads, there is still a need to survey the diverse contexts in which macropropositions of Vedānta have been deployed with colonial scripts in modern discourses of spirituality and imagined communities of global denominationalism (Casanova Reference Casanova and de Vries2008; van der Veer Reference van der Veer2014).

Orientalist descriptions of Vedānta and subsequent attempts to discern symbolic, esoteric, hidden meanings of the Upaniṣads serve to silence unauthored utterances (apauruṣeya-śabda) of the Vedas still heard in the Advaita sampradāya. Cognitive models that fail to integrate Upaniṣads as a verbal means of knowledge (śabda-pramāṇa) are based on imperial encounters that replace networks of distributed and social causal cognition in teacher-student lineages (guru-śiṣya-paramparā) with theory-practice binaries relevant to mind-altering practices of the Yoga tradition, freethinking Orientalists, and Hindu missionaries. Expecting Vedānta to be a verbal means of knowledge does pose significant challenges for readers interested in classifying the Vedas as revealed scripture in world-religions discourse or as an Indian variant of philosophical idealism. For discourse comprehension of traditional Vedānta, nevertheless, Upaniṣads must be conceptualized not simply as the final results of a mental process but as śabda-pramāṇa.