Introduction

Until the end of the nineteenth century, European cities were dominated by “urban oligarchies.” With the rise of the nation-state and growing urbanization, these urban elites have since progressively lost their dominance (Le Galès and Therborn Reference Le Galès, Therborn, Immerfall and Therborn2010). This general observation particularly applies to the Swiss case. Due to the absence of a national monarchic tradition, court society and nobility (Elias Reference Elias1969), social and political power in the territory of modern Switzerland was decentralized and largely concentrated in the hands of patrician families in different cities. These families, who benefitted from statutory privileges in Swiss cities before the French revolution, continued to hold power positions in the economic, political, academic, and cultural spheres of urban activity (Perroux Reference Perroux2006; Sarasin Reference Sarasin1998; Tanner Reference Tanner, Brändli, Gugerli, Jaun and Pfister1990, Reference Tanner1995). This article focuses on the evolution of this “patrician structure” (Sarasin Reference Sarasin1998), which typically involves occupying positions of power and developing multiple kinship ties between families, over the course of the twentieth century.

There are a few salient examples of such long-lived intergenerational transmission of power positions up to the present day. For instance, in 2022, André Hoffmann and his nephew Jörg Duschmalé, two members of the Hoffmann-La Roche patrician family dynasty in the city of Basel, embody the family’s interests on the board of directors of the famous pharmaceutical company Roche. They represent at least fifteen members of the Hoffmann family who, together, still hold a majority of voting rights of the company. Similarly, the Pictet family in Geneva has perpetuated its position as one of the largest and most long-lasting family-owned private banks in the world (Mach and Araujo Reference Mach and Araujo2018). By forging alliances with other patrician families, the Pictets have not only maintained their influence in private wealth management, but they have also extended the family’s activities to the cultural sphere and held leading positions in fine art societies.

These examples raise crucial questions for the Swiss patriciate – and indeed the intergenerational transmission of influence and power – at large. Did these families succeed to perpetuate their domination in the twentieth century, and if so, which ones? What role did kinship networks and family ties play in this regard? Can we observe differences in dynastic power preservation dynamics across cities and spheres of activity? To answer these questions, we draw on a systematic database of urban elites, i.e., individuals who occupy power positions in the three major Swiss cities (Basel, Geneva, and Zurich) in 1890, 1910, 1937, and 1957, and their kinship ties with other elites. Using social network, kinship, and sequence analysis, we provide a comprehensive and interdisciplinary investigation of the Swiss patrician elite’s evolution over seventy years.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we methodologically innovate by combining a long-term analysis of positions of power and ties at both an individual level and at a family level. Thereby, our analysis allows to uncover different varieties of dynastic preservation that might be at play in other contexts as well. Second, we provide empirical evidence for the long-lasting presence of (some) patrician families in urban power structures of the twentieth century. We thus show that even in a case like Switzerland – without court and monarchic tradition – a part of the ancien régime elite remained powerful. Beyond the Swiss case, we broader contribute to the literature on power and kinship through an interdisciplinary approach combining historical and sociological perspectives.

The article is structured as follows: we first discuss existing literature that addresses the entanglement of power and kinship and present existing research on the Swiss patrician structure. Second, we present our data and research strategy. Third, our empirical section proceeds in four parts by analyzing: (1) the presence of patrician family members in power positions, (2) their kinship ties with other patrician and non-patrician elites, (3) the differences between patrician families’ trajectories, and (4) survival strategies of those families who retained positions of power in the twentieth century. Finally, our conclusion comes back to our major results, underlines some limitations of our study, and presents further potential research avenues.

The entanglement of power and kinship

In the past decades, historians of modern Europe have closely examined the extent to which the ancien régime elite may have retained positions of power over the long term. In his classic study of the Persistence of the Old Regime, Arno Mayer (Reference Mayer1981) showed that, across Europe, this elite still occupied leading positions in the political and economic spheres up until 1914, and that this presence was never seriously challenged by the rising bourgeoisie. German historiography has shown that the power of Junker families remained unchallenged well into the twentieth century, despite the massive industrialization which the country underwent (Carsten Reference Carsten and Wehler1990). Likewise, French historiography has documented the continued presence of noble families in elite positions during the nineteenth century (Beck Reference Beck1981; Charle Reference Charle1988; Higgs Reference Higgs1987). The few studies that have explored the destiny of these families in the twentieth century provide ambiguous findings. Cannadine (Reference Cannadine1990) claimed that British aristocratic families witnessed a steady and relentless decline from the 1880s to the 1930s, in terms of both wealth and power. By contrast, Mandler (Reference Mandler, Conze and Wienfort2004) stresses the revival of aristocratic wealth since the 1950s, after a sharp decline in the fortune of the British aristocracy in the first half of the twentieth century. For the Netherlands and Austria, scholars have shown that nobles did succeed in preserving positions of power in the twentieth and twenty-first century, notably in the economic sphere (Dronkers and Schijf Reference Dronkers and Schijf2004; Korom and Dronkers Reference Korom, Dronkers, Kuiper, Bijleveld and Dronkers2015).

To explain this continuity, historians, and social scientists have increasingly turned their gaze to kinship, which refers to the set of bonds between individuals within a society, established through consanguinity or marriage. In the context of early modern Europe, Haldén (Reference Haldén2020) has argued that the capacity of elite families to build strong and extensive kinship networks directly explains the successful state building. In a similar fashion, the role of family strategies in securing privilege and political positions has been studied by Adams (Reference Adams2005), in the context of the Dutch Golden Age, whose political organization was characterized by what she called a “familial state.” This entanglement of power and kinship extends beyond Europe, as shown for example by Del Valle and Larrosa (Reference Del Valle, Larrosa, Diebolt, Rijpma, Carmichael, Dilli and Störmer2019) for the case of Buenos Aires (1776–1810), where individuals belonging to families with numerous ties had a higher probability of sitting on the city council. Focusing on the baby-boomer generation, Toft and Jarness (Reference Toft and Jarness2021) showed that members of the Norwegian upper class are not only more likely to marry within the upper class, but that they are also more likely to marry within the same segments of the upper class. Such homogamous matrimonial strategies, i.e., the tendency of members of elite families to marry among their peers, has been shown to be a crucial driver of dynastic preservation in various national contexts (Augustine Reference Augustine1994; Johnson Reference Johnson2015; Nakaoka Reference Nakaoka2022; Santiago-Caballero Reference Santiago-Caballero2021). According to O’Brien (Reference O’Brien2023), the persistence of upper-class families is to be understood not as collections of distinct dynasties, but as complex, durable family webs.

Strategic kinship alliances have moreover been identified as a crucial factor for the long-term success of family businesses (Colli Reference Colli2003; Ginalski Reference Ginalski2015) by providing such firms with competitive advantage in times of economic or political turbulence (Berghoff Reference Berghoff2006). Family networks also played a key role in the growth and prosperity of famous banking dynasties such as the Rothschilds (Landes Reference Landes2006) or the Schroders (Roberts Reference Roberts1992). Similar mechanisms have been identified in the industrial sector. Farrell (Reference Farrell1993) studied the case of elite families in Boston in the nineteenth century – the so-called Boston Brahmins – who exerted control over some of the city’s central economic institutions through interlocking business interests and intermarriage.

Of course, despite the proven resilience of some families, there is no mechanical guarantee of status preservation. New elite families emerge, while others decline. The putative tendency of business dynasties to decline after a few generations is known as the “Buddenbrooks effect” (in reference to Thomas Mann’s eponymous novel): children raised in privileged circumstances may develop a propensity to idleness and profligacy, detrimental to the family’s prosperity (Colli Reference Colli2003: 14). Eventually, the degree to which the factors conducive to status preservation end up overriding the dispersion factors depends on a whole array of circumstances.

The Swiss patrician structure

Switzerland represents a specific case among its European counterparts. In the absence of a formal nobility at the national level, the wealthiest layer of local urban bourgeoisies, known as “patriciate” (Tanner Reference Tanner1995), have been able to establish their power in Swiss cities. They differentiated themselves from the rest of the bourgeoisie by imitating the manners of the European aristocracy (Peyer Reference Peyer, Messmer and Hoppe1976: 3–4). Although Swiss cities’ political regimes were formally distinct from each other, they all shared at least three traits that characterize the ancien régime power structure from the late sixteenth century to the beginning of the nineteenth century. First, the patriciate was exclusively endowed with political rights, and therefore benefited from considerable privileges.Footnote 1 Second, co-optation – the transmission of power position within families, from generation to generation – often determined the accession to top political or judicial offices (Barbey Reference Barbey1990: 10–37; Illi Reference Illi2003: 66; Peyer Reference Peyer, Messmer and Hoppe1976: 11). This system was nevertheless not completely impermeable, as some families could ascend to the patriciate, mostly thanks to their economic success (Guyer Reference Guyer and Rössler1968: 413–414). Third, homogamy, highly prevalent among the patriciate, ensured and reinforced the concentration of power among patrician families (Illi Reference Illi2003: 82–84).

Beyond their political activities, patrician families also exerted significant economic influence. They leveraged their diplomatic ties to broaden their commercial network (Peyer Reference Peyer1968; Sayous Reference Sayous1937). Several Genevan families developed an expertise on the underwriting of foreign government debt (Lüthy Reference Lüthy1959), while in Zurich and Basel, family companies concentrated on international silk trade (Peyer Reference Peyer1968; Schär Reference Schär2015). The intergenerational transmission of this wealth was in turn legally secured through family foundations (Familienfideikommiss) (Peyer Reference Peyer, Messmer and Hoppe1976: 19). On top of that, and building on their political power and economic wealth, patrician families also penetrated the intellectual domain (Sigrist Reference Sigrist2004).

The French Revolution deeply affected the Swiss patriciate, especially because the consecutive constitution of the Helvetic Republic led to the abolition of patricians’ political privileges in 1798. In 1815, following Napoleon’s defeat, the ancien régime elite could reclaim its former power, and, in most cities, conservative constitutions got (re)established, reverting the political situation to a status quo ante (Humair Reference Humair2009: 35). This patrician restoration, however, turned out to be short lived. In 1848, the constitution of modern Switzerland initiated the end of patrician privileges.

In reaction to the loss of their political and statutory power, patrician families managed to protect their influence by forming local “patrician structures” based on both the occupation of power positions and kinship ties forged through strategic marital alliances (Sarasin Reference Sarasin1998). They reinforced their attention to the economic and cultural spheres. Originally mostly active in textile trade and production, the patrician families diversified their economic activities towards services (banking and insurance) and other industrial branches (machines in Zurich, chemical industry in Basel). Culturally, the patriciate kept the upper hand; they were, for example, massively represented among the boards of local art societies, as well as in philanthropic activities (David and Heiniger Reference David and Heiniger2019). The patriciate also developed an idiosyncratic folklore, celebrating its long history, embodied in Zurich by the yearly parade of the guilds (Sechseläuten), by the celebration of the battle against the Savoyards of 1602 in Geneva (Escalade), and the Basel Carnival (Basler Fasnacht).

The boundaries between the patriciate and the non-patrician economic elite were however never completely impermeable (König Reference König2011). Although homogamy was prevalent in some cities, marriages with non-patrician elites could serve economic ends. In Basel, for example, economic cooperations were built on marital alliances between descendants of the patricians of the textile industry and new elites of the chemical industry. As defined by Sarasin (Reference Sarasin1998), the “patrician structure” specifically refers to the context of end-of-nineteenth-century Basel and the ability of patrician families to perpetuate their dominant positions, despite the formal loss of their statutory privileges. However, less is known about the evolution of these patrician families’ power in the twentieth century.

Swiss urban elites between 1890 and 1957: Data and empirical strategy

Power positions of Swiss urban elites, 1890–1957

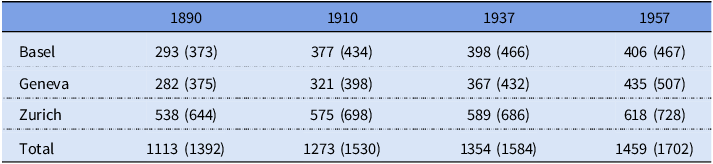

To document the evolution of patrician families’ power, we constructed an original and systematic database of urban elites, composed of all individuals who occupied power positions in major and enduring institutions of the economic, political, academic, and cultural spheres in the cities of Basel, Geneva, and Zurich in four benchmark years: 1890, 1910, 1937, and 1957. We follow a positional approach (Mills Reference Mills1956), which considers the occupation of such power positions as crucial for governing cities.Footnote 2 Table 1 displays the sample size by cities and benchmark year.

Table 1. Sample size by city and benchmark year

Note: N individuals and N mandates (in parentheses). The total for the individuals can be smaller than the sum of the different lines since the same individuals can occupy elite positions in different cities in the same benchmark year.

For the economic sphere we collected information on all the committee members of the regional chambers of commerce as well as directors of the most important companies of the three cities’ leading economic sectors. This includes the major banks and insurance companies for the financial sector; for Basel, all the major textile (until 1937) and chemical-pharmaceutical companies; for Geneva, the major watch-making companies, as well as a few other industrial companies; and for Zurich, all the major companies from the machine industry. The total number of companies varies from 49 in 1890 to 45 in 1957. For these companies, all CEOs/general directors and directors’ board members were considered.Footnote 3 For the political sphere, we included all members of the cantonal (regional) and local (city) parliaments and governments for Geneva and Zurich, whereas in Basel, where the city’s territory fully coincides with the canton, only the members of the cantonal parliament and government were considered. For the academic sphere we include all full and extraordinary (associate) professors of the three cities’ universities. Finally, the committee members of the three cities’ fine art societies are included as urban elites from the cultural sphere.

Operationalizing patrician families and kinship ties

To document the evolution of patrician families’ kinship ties, we first need to distinguish urban elites who are members of the patriciate, referred to as patrician elites, from those who are not, referred to as non-patrician elites. To do so, we rely on an indicator that captures the moment at which a person’s family obtained the right of citizenship in the cities of Basel, Geneva, Zurich, and Winterthur.Footnote 4 In Switzerland, each Swiss citizen has a legal place of origin. Before the year 1800, i.e., the time before the ancien régime was replaced by the Helvetic Republic, the place of origin – a municipality or a city – determined where a person had political and social rights. Until recently, social rights – e.g., the right to obtain social assistance – were tied to one’s place of origin. And until today, a Swiss citizen’s place of origin is indicated in his/her passport.

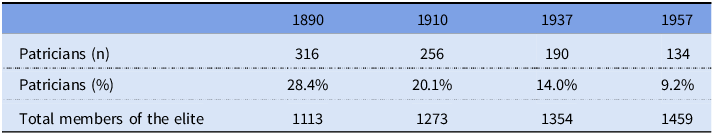

We use the information on the place of origin to determine since when a member of the elite had the right of citizenship in a particular place. To do so, we rely on the Swiss family name book.Footnote 5 This source indicates the last names of all persons that held citizenship rights in a Swiss city or municipality (up to 1962), the year in which citizenship was obtained and where naturalized persons had citizenship rights before. For each family name and place of origin combination of elite members, we, thus, checked when and where that particular family obtained citizenship rights. The obtention of citizenship rights prior to 1800 in one of the four cities listed above defines membership in patrician families. As previously mentioned, those who held citizenship rights before 1800 had strong prerogatives in Swiss cities, for instance, only they were allowed to take political office. Therefore, the time of citizenship obtention in one of the four cities is a good – even if approximative – indicator for whether elites belong to patrician families or not. Table 2 displays the share of patricians among all urban elites.

Table 2. Descendants of patrician families among urban elites per cohort

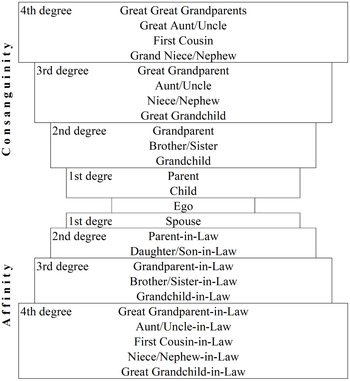

To capture kinship ties of those urban elites that are patrician family members, we systematically identified their parents, grandparents, spouse, and grandparents-in-law. Sons and daughters were also identified when provided, even if not on a systematic basis. Most information was collected through four main sources: the Historisches Familienlexikon der Schweiz (hfls.ch), the website of the genealogical society of Geneva gen-gen.ch, stroux.org which has fine-grained data on the genealogy of Basel’s patrician families, and the Bürgerbuch der Stadt Zürich (1882–1926). From the extensive information collected, we built a network of all kinship ties as a stack of individual relationships through either consanguinity (ascendance and descendance) or affinity (marriages). We were then able to identify the number of different types of kinship ties that each patrician elite has with other patrician and non-patrician elites. The different types of kinship ties refer to the distance of kinship and is differentiated into consanguinity and affinity distance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Consanguinity and affinity distances (from ego).

By combining information on power positions and kinship, we were able to identify all families who had a member that occupied a power position in 1890, 1910, 1937, and 1957. Each familyFootnote 6 was characterized by the number of kinship ties with other elites, patrician and non-patrician, and the presence (or absence) of one of their members in urban power positions for each benchmark year. As the relevant kinship distance, we follow the existing literature and employ a threshold at the 6th civil degree of kinship – up to the second cousins – beyond which individuals generally do not know their family members (Mathieu Reference Mathieu, Waren Sabean, Teuscher and Jon2007; Rappo Reference Rappo2021; Ruggiu Reference Ruggiu2010). We then calculated the average number of kinship ties for each family that had a member among the urban elite in a benchmark year and used sequence analysis to process this longitudinal information. Sequence analysis is specifically designed to identify patterns in chronological sequences of states (Abbott and Hrycak Reference Abbott and Hrycak1990; Blanchard et al. Reference Blanchard, Bühlmann and Gauthier2014). We calculated the degree of similarity between patrician families’ power and kinship trajectories from 1890 to 1957 through an optimal matching process (Abbott and Tsay Reference Abbott and Tsay2000). We then performed a hierarchical clustering using the Ward’s method (MacIndoe and Abbott Reference MacIndoe, Abbott, Hardy and Bryman2004; Studer Reference Studer2013) to group trajectories into types, that are as similar as possible and as different as possible from other types. Finally, we study the association of particular family trajectories with cities, spheres of activity, and the number of power positions occupied by family members to assess whether particular family trajectories are over- or underrepresented in certain cities or spheres of power (Husson et al. Reference Husson, Lê and Pagès2017).

The evolution of patrician families’ power (1890–1957)

To analyze the evolution of patrician families’ power in the three cities, we proceed in four steps. First, we analyze the presence of patrician elites in power positions in different social spheres in the three cities. Second, we provide an overall descriptive analysis of the network of patrician elites’ kinship ties with other elites. Third, we move to the level of the family and provide a typology of patrician families that have retained power position over the 70-year period. Finally, we identify three different survival strategies based on these trajectories and illustrate them with three examples.

Patrician elites’ retreat from power positions

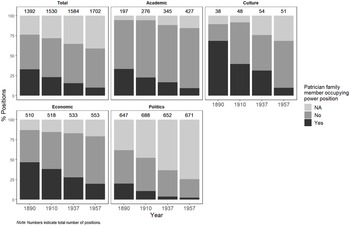

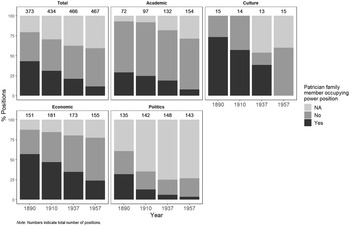

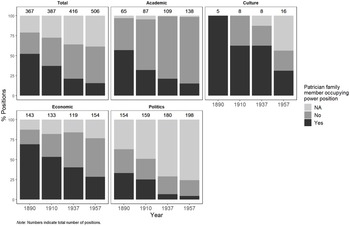

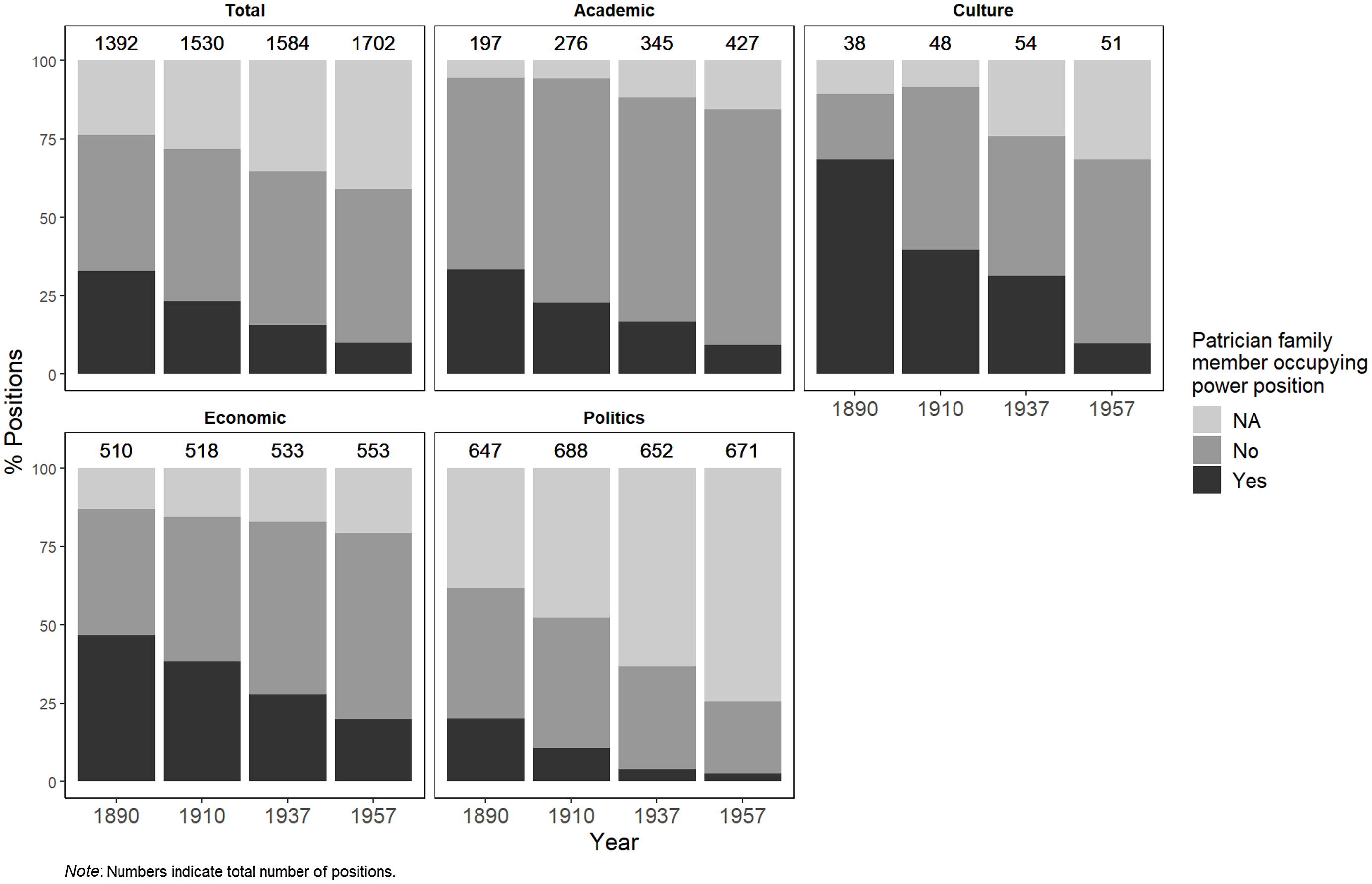

We start our analysis with an overview of the power positions that patrician family members held in the academic, cultural, economic, and political spheres from 1890 until 1957. Figures 2–5 show the percentage of positions that were occupied by patrician family members across and by cities. When an elite member holds mandates simultaneously in multiple spheres, we counted it in each sphere. Across all spheres and cities, we see a clear decline in the percentage of positions occupied by patrician family members over time (Figure 2). This suggests that the power positions held by patrician families in these cities overall declined from the end of the 19th until the middle of the twentieth century.Footnote 7

Figure 2. Three cities combined: Occupation of power positions by patrician elites (%).

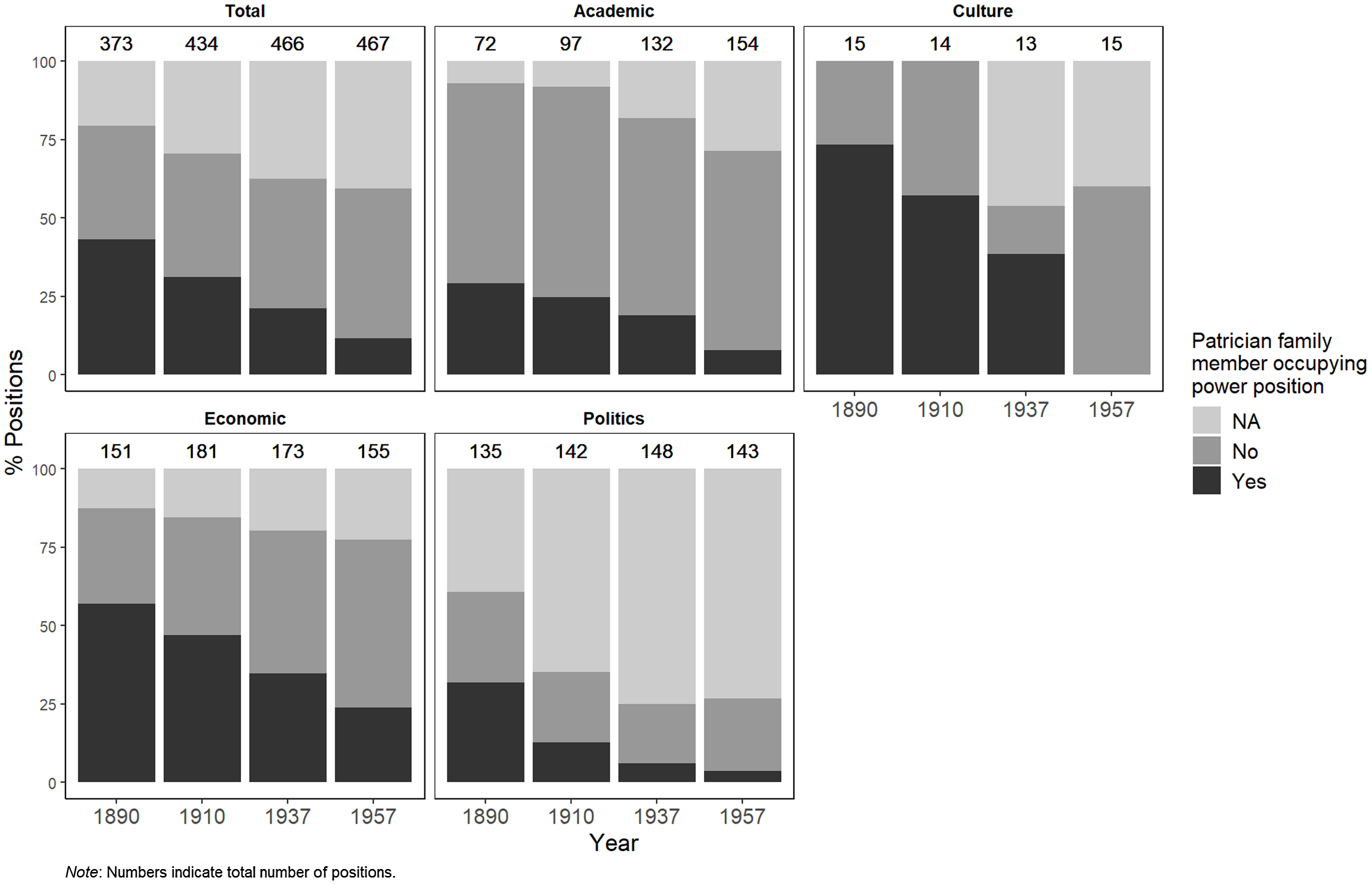

Figure 3. Basel: Occupation of power positions by patrician elites (%).

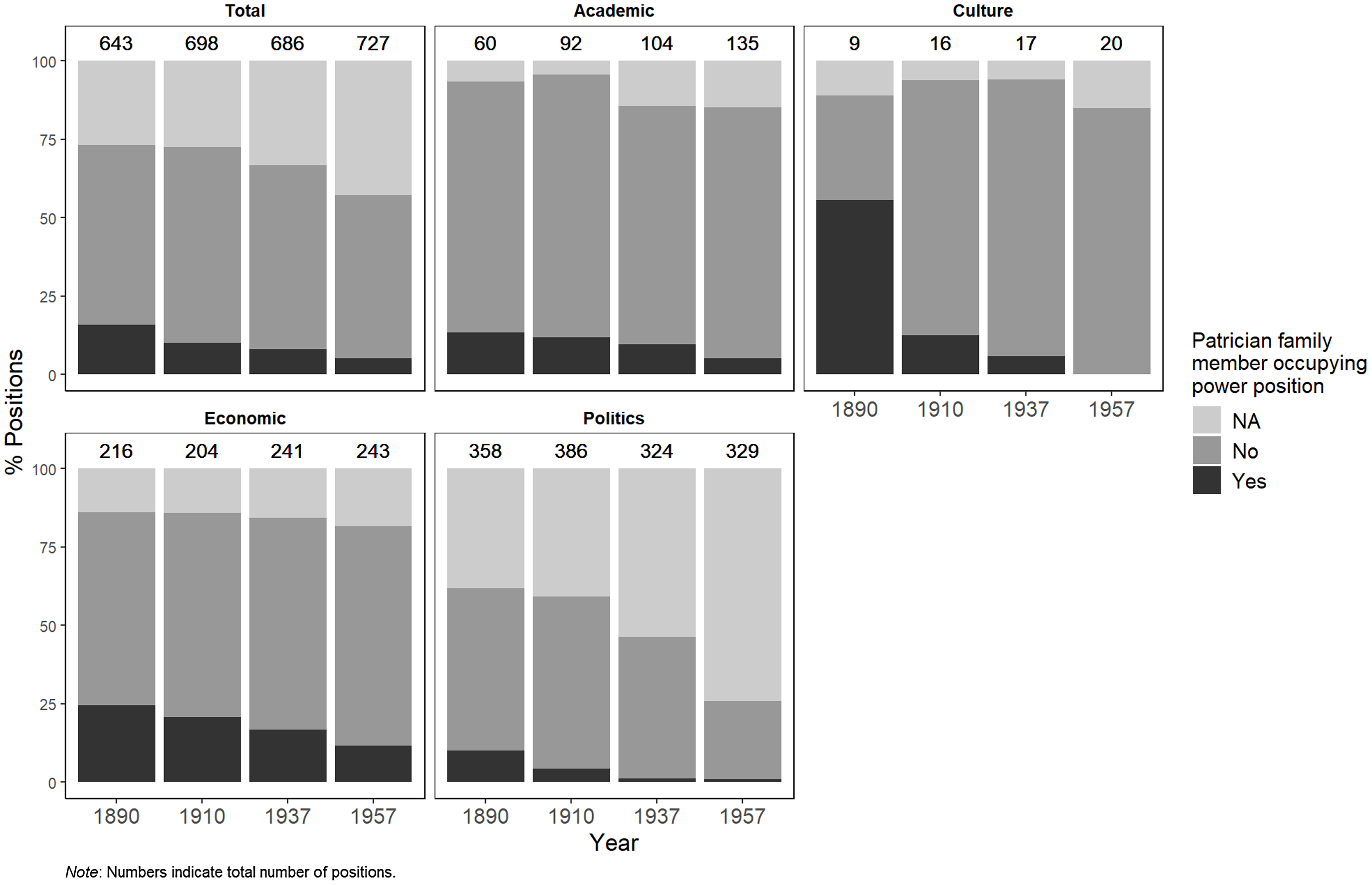

Figure 4. Geneva: Occupation of power positions by patrician elites (%).

Figure 5. Zurich: Occupation of power positions by patrician elites (%).

Yet, a closer look also shows some stark differences both between cities and across spheres (Figures 3–5). Between cities, we can see that the percentage of positions occupied by patrician family members is much higher in the cities of Basel and Geneva compared to Zurich. One explanation for this might be that the patrician families in Basel and Geneva were less challenged by newcomers than in Zurich, because both Basel and Geneva have been independent city-states for a long time, whereas the city of Zurich was the head of a territorial state with a sizeable hinterland. Patrician families in Zurich and Winterthur also had to face a much fiercer contestation from the “democratic movement” during the second half of the nineteenth century; this movement was particularly strong among the rural population (artisans, small industrialists, peasants, but also workers), that opposed the domination of the old patrician families. By contrast, in Geneva and particularly in Basel, it was only when the labor movement grew stronger at the beginning of the twentieth century that these families lost their grip over the cities to some extent. Already at the outset, i.e., in 1890, the dominant position of patrician families was much weaker in Zurich than in the two other cities.Footnote 8

Concerning the differences between social spheres, all figures show similar variation across cities. At the end of the nineteenth century, the fine art societies of the three cities were clearly dominated by patrician family members in all three cities. While this progressively changed in the coming decades, patrician families remained very important in the cultural sphere until the end of the 1930s – at least in Basel and Geneva. Even though the sample size for the committees of the three art societies is relatively small, the clear overrepresentation of patrician families, especially for the first benchmark years, confirms the strong investment of these old families in cultural institutions (for a similar observation, see Hiler [Reference Hiler1995] for the reading society of Geneva, and Kriemler [Reference Kriemler2017] for the one of Basel).

The second most important sphere dominated by patrician families is the economic one, again particularly in Basel and Geneva. Here, major companies – especially private banks, but also companies from the textile, the chemical, and the watch-making industry – were, or still are, led or in possession of patrician families. Both in Basel and Geneva, more than 50% of all positions in company boards and chambers of commerce were held by patrician family members in 1890, and they continued to play an important role in the decades to come. By contrast, patrician families in Zurich were holding only 25% of all positions in the economic sphere at the same period, which indicates a weaker influence than in the other two cities. This strong presence of patrician family members in the leading positions of the most important companies is also illustrative of the strength and longevity of family capitalism in Switzerland (Ginalski Reference Ginalski2015).

Patrician family members were also particularly active in the academic sphere, where some true scientific dynasties existed. As underlined by Horvath (Reference Horvath, Pfister, Studer and Tanner1996), major Swiss universities, especially Basel and Geneva, were dominated by two categories of professors until the first world war: 1) offspring from local patrician families and 2) foreign professors. If we do not consider foreign professors in data presented in Figures 2–5, patrician elites represented more than half of the Swiss professors in Basel and Geneva for the years 1890 and 1910. Again, this was less the case in Zurich. Yet, patrician domination prevailed somewhat less long than in the economic and the cultural sphere.

Finally, in the political sphere patrician family members were in a minority in all three cities since the end of the nineteenth century. Since access to political positions is subject to being elected by voters and since patrician families only made up a small portion of a city’s population, they faced competition in this domain from the moment at which general elections were held – i.e., from at least 1848 onwards – in all cities. In all three cities, challenger movements formed first within the bourgeoisie of the cities – composed of citizens that had substantial resources but were not part of traditional patrician families – and later by the labor movement (see Lüthi (Reference Lüthi1963) on the decline of patrician presence in the cantonal parliament of Basel between 1870 and 1914). Indeed, in the 1930s, all three cities experienced periods where the labor movement and socialist parties were in a majority position and dominated government and/or parliament.

Overall, we observe a general decline in the positional power of patrician families in all three cities and across spheres from 1890 to 1957. Yet, there is significant variation in the extent of the decline across cities and spheres of power. The variation across spheres of power can largely be explained by the different selection processes to access power positions. Whereas selection in the economic and cultural spheres is based on co-optation, that tends to reproduce dominant groups, selection in the political sphere follows democratic election procedures, which favor an elite composition that is more representative of the population as a whole; finally, the recruitment logic in the academic sphere follows more meritocratic and scientific criteria of excellence.

Patrician elites’ kinship ties

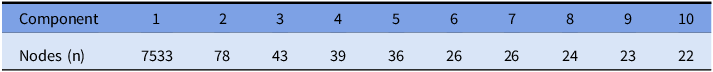

In this part, we focus on patrician elites’ kinship ties and provide some descriptive insights on the network of all relationships between patrician elites and other positional (non-patrician) elites between 1890 and 1957. All generations, cohorts, and cities combined, the total network of kinship ties comprises 10,711 individuals (nodes) and 13,308 edges (direct kinship ties including all parents of the patrician positional elite). The network consists of 492 components, with one very large component and multiple very small components with a minimum of three individuals (Table 3).

Table 3. Size of the ten first components

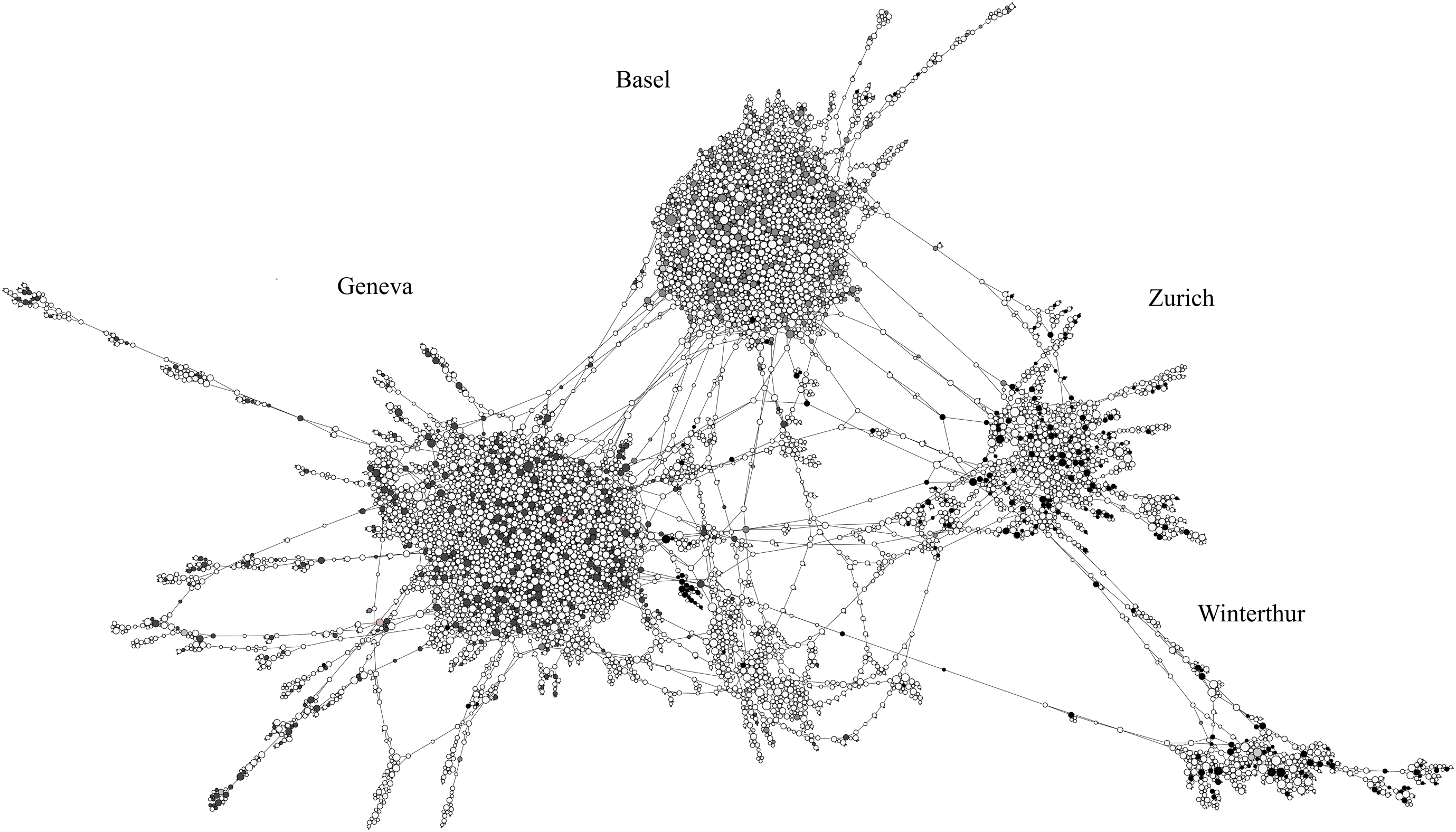

The presence of many small components next to the main component indicates that the elites are globally very connected through their kinship ties. It also indicates that the addition of a missing link does not significantly alter the overall structure of the network. We are, thus, confident in the robustness of our analysis, given that these missing links are unlikely to significantly change the results at four and six degrees of kinship. Figure 6 displays the principal component of the network, which contains 7,533 nodes (70.3%) and 10,282 edges (77.3%).

Figure 6. Network of kinship ties: biggest component (70.3% of nodes, 77.3% of edges).

Colors of nodes refer to the cities: Geneva on the left (dark grey), Basel at the top (lighter grey), Zurich and Winterthur on the right (black). A few individuals in light grey are affiliated with at least two cities simultaneously.

The network of kinship ties does look like a “spider’s web” with multiple clusters (Lüthy Reference Lüthy1959; Perroux Reference Perroux2006), which underlines the polycentric character of patrician kinship relationships in Switzerland. Patricians from Basel, Geneva, and the two cities of the Zurich region form distinct hubs. The very few “inter-city” marriages, i.e., between patrician elites from different cities, is particularly striking. This shows the strong homogeneity of patrician families and echoes the decentralized nature of power in Switzerland. The patrician elites of Zurich appear to be less connected to each other (or at greater kinship distances) than those of Basel and Geneva, which is in line with the greater openness of their matrimonial practices with the non-patrician elite observed by historians (Tanner Reference Tanner, Brändli, Gugerli, Jaun and Pfister1990, Reference Tanner1995). In total, we find 1,017 urban elites in the biggest component, which correspond to 19.6% of all 5,199 urban elites from the study sample. Indeed, some categories of elites are, without much surprise, quasi-excluded from the component. For instance, only 23 foreigners are included, and only five out of the 563 left-wing political elites. Conversely, 696 patrician family members are included, which corresponds to 81% of all patrician members of the urban elite.

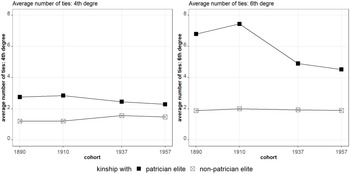

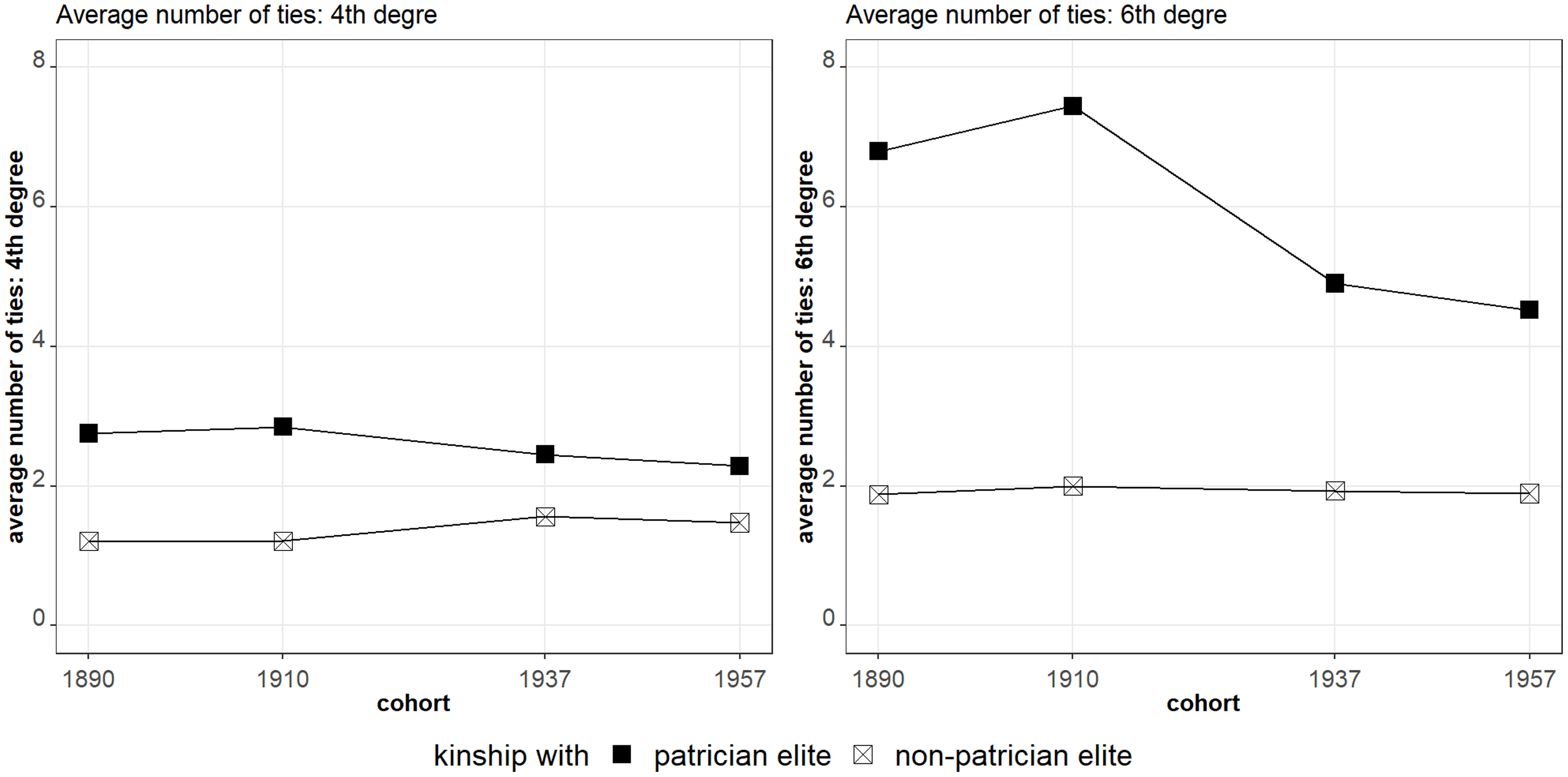

From this network of kinship ties, we also calculated the average number of ties each patrician elite has with other non-patrician elites of the same benchmark year, as displayed in Figure 7. On the left, the figure illustrates the average number of ties at the fourth degree; on the right, at the sixth degree.Footnote 9

Figure 7. Average number of ties of patrician elites with another elite (patrician or non-patrician).

From Figure 7, we observe a remarkable stability of the average number of ties at the fourth degree of kinship, that is to the first cousins, while there is a certain decline at the sixth degree. The observation that kinship ties remain constant at a closer distance (but decline at a higher distance) can be an indication of increased social closure: a fewer absolute number of patrician elite members strive to maintain kinship ties to other patrician elites – and consequently become even more homogamous in their alliance behavior. An alternative interpretation is that the stability in the average number of kinship ties with other patrician elites is due to a “survivor bias”: those patrician elites that continue to occupy power positions in later cohorts potentially belong to those families that are the most integrated in kinship networks. In older cohorts, the patrician elite might consist of a more diverse group of patrician families and hence also include patrician elites that were less well integrated in the patrician kinship network. Stronger kinship networks might, thus, have been conducive to securing a position among the urban elite. When considering kinship ties to the 6th degree (down to second cousins), we observe a decrease in the average number of ties with patrician elites, which is however not compensated by an increase in the number of links with non-patrician elites. This suggests that patricians who occupy elite positions tend to favor matrimonial alliances with other patrician families over those with the new elite.

In line with the literature, these general trends suggest that the role of kinship in the access to power did not vanish in the first half of the twentieth century (Augustine Reference Augustine1994; Johnson Reference Johnson2015; Santiago-Caballero Reference Santiago-Caballero2021). Our results suggest that the transmission of elite positions through family co-optation, i.e., the transmission of positions within the family circle, still represented an important mechanism of elite reproduction – even if among a smaller proportion of the urban elite. This co-optation operated both vertically, through father-son relationships (typically the transmission of a family business), and horizontally, through marriage. These observations, in combination with the results of the section 5.1 (pointing to the decline of patrician representatives in power positions) suggest that family co-optation, as a mechanism of power preservation, was not strong enough to prevent the access of new social groups to power positions. Put differently, the declining presence of patricians in power positions is thus not to be explained by a dilution of family networks. In addition, our results show that the patrician elites were overall quite conservative in their alliance strategies, in line with the patterns observed in various national contexts (Korom and Dronkers Reference Korom, Dronkers, Kuiper, Bijleveld and Dronkers2015; Santiago-Caballero Reference Santiago-Caballero2021; Toft and Jarness Reference Toft and Jarness2021).

However, such an aggregate measure of individuals’ kinship ties fails to show variations in the power positions held at the level of the families themselves. When we look at the families whose members occupy the highest number of power positions, we find clear hierarchies: In Basel, the Burckhardt, Sarasin, Vischer, Merian, and Iselin families occupy 72, 41, 40, 23, and 21 power positions, respectively. In Geneva, the five most important patrician families are the Pictet (29 positions), Hentsch (16), Oltramare (15), Gautier (14) and Turrettini (13). In Zurich and Winterthur, the Sulzer (27), Escher (17), Huber (14), Pestalozzi (14), and Schulthess (14).Footnote 10 To further explore these differences across patrician families as well as the diachronic variation in their presence among the urban elite, the following two empirical sections are dedicated to an analysis at the level of the family.

Different patrician families’ trajectories

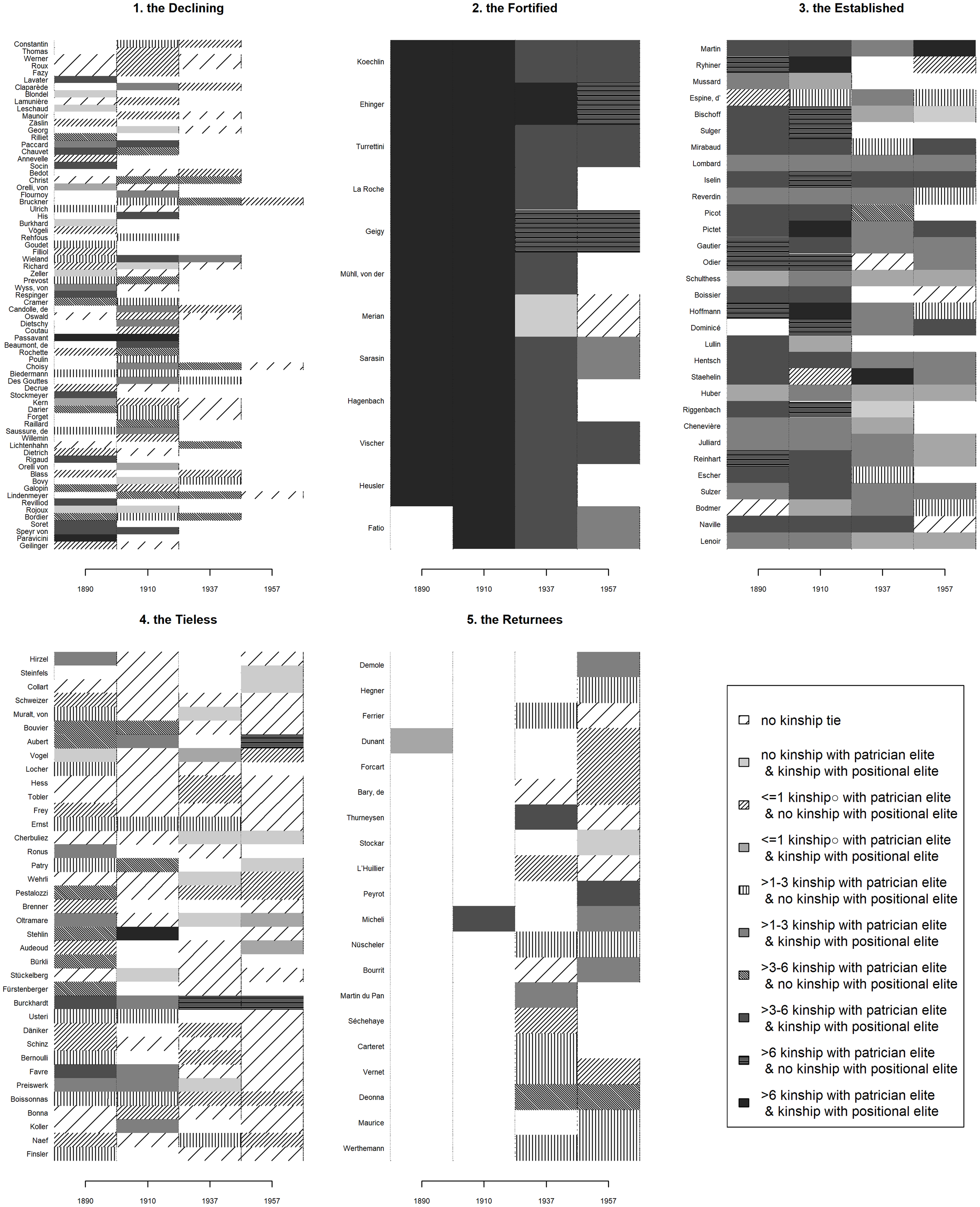

To capture more precisely the decline and the persistence of different patrician families in urban power structures, we look at the evolution of patrician families’ presence or absence in urban power positions as well as their kinship ties over the four benchmark years (1890, 1910, 1937, 1957). For each benchmark year, we characterize families based on whether one of their members holds a power position, as well as the number of kinship ties of their members with other patrician elites and/or with other non-patrician elite. This yields eight different states that a patrician family can take on in each benchmark year (see Figure 8). States are left blank if the family members do not hold any power position in a given benchmark year. The chronological analysis of these states through sequence analysis then provides us with different family trajectories. In total, we identified 171 patrician families, each holding at least one position of power in at least one benchmark year. A significant part of them (41.5%) have lost their access to power positions, and others managed to access again power positions (17.7%), and the remaining 40.8% show rather stable trajectories in urban power positions. We then use cluster analysis to group those family trajectories that are most similar to one another together.Footnote 11 These groups are visualized in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Five different families’ trajectories (1890–1957).

From Figure 8, we see five clusters, which we name 1) the Declining, 2) the Fortified, 3) the Established, 4) the Tieless, and 5) the Returnees. In what follows, we describe the features of each cluster regarding its power and kinship trajectory as well as its over- or underrepresentation in particular cities and spheres of activity. This information is summarized in Appendix II together with the distribution of kinship ties for each cluster.

Cluster 1: The Declining (n=71 families, 41.5%)

These are patrician families who are not represented anymore in power positions in 1957. Their family ties are essentially with other patricians and are globally few in numbers. Moreover, they occupy only few positions of power already in 1890. Despite various individual situations, in all cases, their kinship ties seem insufficient to secure them access to power positions over the long term. Geneva families are over-represented among this category. This could be explained by the fact that patrician families were numerous in Geneva – 367 families were given the patrician privilege until 1792 – and hence power was more diluted. These trajectories are overrepresented in the cultural sphere, which is in line with the observation that the strong investment of patrician families in cultural institutions has decreased during the first half of the twentieth century, especially after 1930. These rather dominated families therefore also appear to be the least stable over time, in contrast to the economic elite, as we will see later.

Cluster 2: The Fortified (n=12 families, 7%)

The first group of families who have retrained significant power positions is characterized by an impressive number of kinship ties with patrician and non-patrician elites. It is the most connected group with others patrician elites. In 1890 and 1910, these families had an average of more than 6 kinship ties per family member to the patrician elites. These very dense family networks started to erode from 1937 onwards, notably with non-patrician elites (see Appendix II). However, these families secure their position among the urban elite (at least) until 1957. This group, as we will develop with the example of the Geigy family in the next section, typically illustrates the use of homogamous alliances and family co-optation as mechanisms of power preservation. Basel patrician families are typical of these very conservative strategies of social closure. To some extent, this closed family structure seems to correspond to a permanence of the patrician structure in Basel identified by Sarasin (Reference Sarasin1998).

Cluster 3: The Established (n=31 families, 18.2%)

Similar to the Fortified, the Established are patrician families who remain among the urban elite and develop kinship ties with both patrician and non-patrician elites. They however differ from the Fortified in two aspects: a lower average number of kinship ties with patrician elites, and a higher proportion of kinship ties with non-patrician elites especially from 1937 onwards. By contrast, the Fortified were rather little connected with non-patrician elites in the middle of the 20th century – even though they exhibited a period of greater openness until 1910. The Established do occupy a very large number of power positions. Such family trajectories are overrepresented in the economic sphere, i.e., patricians at the head of important family companies whose persistence in power positions relies on both co-optation and alliances strategies (Ginalski Reference Ginalski2015). Nevertheless, appointing the right people to leadership positions sometimes requires recruiting people from outside the owning family, as we will illustrate with the case of the Pictet family in the next section. Forming alliances (through marriage) with non-patrician families is a strategy for broadening the pool of potential candidates for succession to management positions or on the board of directors in these family businesses, while keeping them under the family’s control (Colli Reference Colli2003; Farrell Reference Farrell1993).

Cluster 4: The Tieless (n=37 families, 21.6%)

These are patrician families who manage to remain in power positions over the long term, although with some periodic absences in power positions. Most often, these families have zero or only few kinship ties to patrician and non-patrician elites. Patrician families from Zurich are typical of this group. The new elite challenged the patricians earlier in Zurich than in Basel and Geneva. The strong development of the region, especially as a major economic hub in Europe, allowed individuals from more diverse backgrounds to rise to positions of power. As this development progressed, particularly after the 1930s, the patrician minority became increasingly isolated from the power elite. These trajectories suggest that these families did not rely on forging alliances through kinship ties with other families, such as the Fortified and the Established, to secure their access to power. More broadly, the Tieless seem to embody an alternative to homogamous alliances with other elites as a crucial driver of dynastic preservation (Santiago-Caballero Reference Santiago-Caballero2021; Toft and Jarness Reference Toft and Jarness2021).

Cluster 5: The Returnees (n=20 families, 17.7%)

Finally, there are patrician families who hardly ever held power positions between the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. However, they managed to access power positions from the 1930s onwards. Once in power, they mostly shared kinship ties with other patrician families. Their kinship ties with non-patrician elites are much more tenuous, or even non-existent. Despite their patrician status, similarly to the Declining category, these families correspond to a dominated fraction of the patriciate between 1890 and 1910 insofar as they do not manage to reach many power positions. Without being able to put forward a causal explanation, it is nevertheless interesting to note the tendency of these families to entertain alliances with the patriciate in power, a group that is strongly endowed with resources, particularly symbolic capital, rather than with other elites.

The distinction between these five groups allowed us to show important variations between families, but also across cities. As shown in section 5.1, patrician families in Zurich are less well-represented in power positions than those in Basel and Geneva. This observation is also confirmed when we look at the family trajectories of the Tieless, which are marked by punctual periods of absence in power positions and very few kinship ties to both patrician and non-patrician elites. This family cluster is typical of the Zurich patrician elite. The analysis of family trajectories also helps to highlight differences between Geneva and Basel. While Basel is composed of a small number of very closely related families typical of the Fortified, Geneva has many patrician families, many of which are among the Declining, even though some Geneva families, especially in the economic sphere show a remarkable stability over time (e.g., the Pictets).

Three types of survival strategies

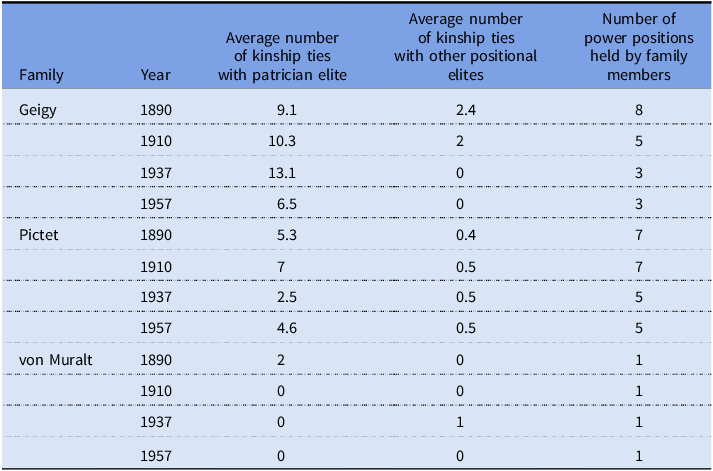

In this last section, we further investigate more qualitatively three different survival strategies. Each example is drawn from one of the three groups of families who have managed to keep their position within the urban elite. The Geigy family from Basel typically belongs of the Fortified category and represents an enlightening case of patrician families that built strong ties mostly with other patrician families in the nineteenth century and perpetuate them between 1890 and 1957. The case of the Pictet family from Geneva relates to the Established and allows for a better understanding of the role of both co-optation and alliances in maintaining the power of a patrician family over time. Finally, the von Muralts from Zurich illustrate the Tieless and epitomize the structural limits of patrician reproduction. Table 4 summarizes the kinship ties and the number of positions held by members of the three families.

Table 4. Kinship ties and the power positions held by members of the three families

Originally from Basel, the Geigys acquired the status of “bourgeois” in 1639 through a marriage between Thomas Geigy, a miller, and patrician Katharina Merian. The dynasty started to become influential in the economic sphere in the mid-eighteenth century. In 1758, Johann Rudolf Geigy-Gemuseus (1733–1793) opened a drugstore, J.R. Geigy, which by the end of the twentieth century had evolved into Novartis, a leading global pharmaceutical company. Thanks to his marriage to patrician family member Anna Elisabeth Gemuseus and the marriage of his son Hieronymus to another patrician Charlotte Sarasin, Johann Rudolf built an extensive kinship network with local patrician families, helping him to develop his business of drugs, dyes, and chemicals. More than 150 years after the creation of the family business, the Geigys show an impressive stability in terms of succession and ties with other patrician families. Johann Rudolf Geigy-Merian (1830–1917), who was running the Geigy company in 1910, symbolizes the original alliance between the Geigys and the Merians. He would continue to co-opt his family, transmitting director positions to his sons, Rudolf Geigy-Schlumberger (1862–1943) and Karl Geigy-Hagenbach (1866–1949), each of whom was married to a patrician wife.

Women also played a central role in securing the dynasty’s control over power positions and its position within the patrician structure. The two daughters of Johann Rudolf Geigy-Merian, Maria (1856–1933) and Louise (1858–1879), married patrician private bankers. Maria’s grandson, Alfred Wieland-Zahn (1869–1959), was a member of the board of directors of the Geigy company until 1940. Adèle Geigy (1827–1903), the sister of Johann Rudolf Geigy-Merian, married Alphons Koechlin, a political elite in 1890 coming from another powerful patrician family. Their son, Carl Koechlin-Iselin (1856–1914), also married with a patrician woman, eventually became a director at the Geigy company and their grandson, Carl Koechlin-Vischer (1889–1969), who also married a patrician woman, occupied a top position at Geigy company until his death. The family is thus characterized by the presence of its descendants in positions of power and by almost systematic marriages with other patrician families.

The Pictet dynasty dates back to the fifteenth century, with Pierre Pictet (1426–1481), a landowner coming from a family of peasants acquiring the title of “bourgeois of Geneva” in 1474. Building on this new status, the Pictet family made its fortune by acquiring large estates on the south bank of Lake Geneva, mainly through alliances with patrician families (Roth Reference Roth2010). The power positions occupied by the Pictets were mainly in the political sphere until the Radical Revolution of 1846 brought a modernization of the political institutions making it harder for patricians to transmit their political positions. Although the political influence of the Pictets significantly diminished after 1846, their power has been perpetuated and even reinforced when they entered the banking sector. Shortly before he passed away, Jacob-Michel-François de Candolle, cofounder of the Bank Candolle Turrettini & Cie, asked Edouard Pictet (1818–1878), the nephew of his wife, to become a partner of his bank. Hence, in 1841, through this kinship tie, Edouard Pictet became the first banker of the family. In 1848, he renamed the bank Edouard Pictet & Cie. Since then, and until the present day, the bank has been continuously owned and controlled by a small group of partners, always comprising at least two members of the Pictet family, making it the Swiss bank with the oldest family-owned tradition. The partner position is transmitted within the family from one generation to another, from father to son or to another male family member. Consequently, Edouard Pictet named his son, Emile Pictet (1845–1909), and the grandson of Jacob-Michel-François de Candolle, Ernest Pictet (1829–1909), as his two successors. In his term, Ernest Pictet contributed significantly to the expansion and transmission of economic power of the dynasty. Along with his banking activities, he was also the founder and first president of the Geneva Chamber of Commerce in 1865. Until the middle of the twentieth century, a descendant of Ernest Pictet was always and systematically coopted to represent the clan within the chamber. In 1889, Ernest Pictet named his second son, Guillaume (1860–1926), partner of the bank. Guillaume Pictet pursued the logic of transmission of power to direct family members by selecting his son, Aymon Pictet (1886–1928), and his nephew, Albert Pictet (1890–1969), as new partners. This logic of transmission is similar to what happened with the Geigy company in Basel.

However, there is a difference between the Geigys and the Pictets regarding their ties with other elites. Similar to the Geigys, the Pictets tend to get married to members of local patrician families. These new allies are sometimes offered power positions within the family bank. For example, Guillaume Pictet gave a partnership to his son-in-law, François de Candolle (1903–1942) and his nephew-in-law, Charles Gautier (1886–1974). But unlike the Geigys, the Pictets also develop extensive ties with non-patrician elites coming from what can be called the “new bourgeoisie.” These resourceful families, often occupying positions of power, also have the status of “bourgeois”, but acquired it after 1800 and hence do not enjoy the same “aristocratic” standing. The ties made with this new bourgeoisie follows a class hierarchy. The Pictets usually do not directly marry with this new bourgeoisie but they do share more distant kinship ties, which sometimes facilitate the access to power positions within the family bank. For example, Alexandre van Berchem-Busk (1900–1977), who became a partner in 1930, is a descendant of Alfonse Turrettini, a former partner, and shares a distant kinship with the Pictets. The persistence of the Pictet dynasty, thus, follows a mix between a conservative strategy like the Geigys while embracing the opportunities offered by weak ties.

Compared with the two previous families, the von Muralts in Zurich did not hold as many power positions, nor did they develop extensive ties with patrician and other non-patrician elites. Nevertheless, since the family acquired the citizenship of Zurich in 1566, it has survived and remained in the patrician structure during the entire historical period analyzed. A first explanation of the lack of kinship ties with other elites lies in the specificity of Zurich. As shown in section 5.1, patrician families were less important in Zurich than in the two other cities and had already lost substantial power before 1890. A second explanation might be that the von Muralts could not benefit from a family firm like the Geigy company in Basel and the Pictet bank in Geneva. While the von Muralt did create one of Zurich’s most prosperous silk trading companies (namely Hans Conrad Muralt & Sohn), it was transformed into a limited liability company (Banco Sete AG) early in the twentieth century (1902) and was relocated to Milan, Italy and the family hence lost its control over it. An important family business represents an organizational structure that facilitates the transmission of positions of power and the development of marital strategies with patrician and non-patrician elites. While the von Muralts occupy power positions mainly in the economic sphere, their presence is rather modest with often only one power position in each benchmark year. These power positions are typically not held in family businesses and thus could hardly be transmitted directly. For example, Robert von Muralt-Locher (1826–1906) was Vice-President of the Bank in Zurich in 1890 and Heinrich Conrad von Muralt-Sulzer (1882–1945) was a director at UBS in 1937. Interestingly, each of them was married to a wife from a Zurich patrician family. The daughter of Robert, Amalia (1850–1907), was married to Hans Wunderli-von Muralt (1842–1921), who held elite positions in the economic and political sphere in 1890 and 1910. This suggests that the von Muralt also try to perpetuate their lineage through marital strategies, although in a regional context that offers less opportunities to do so.

Conclusion

Building on a systematic database of n=5,199 urban positional elites in the three major Swiss cities (Basel, Geneva, and Zurich), we combined historical and sociological approaches to assess the presence of patrician family members in power positions as well as their kinship ties over seventy years. With the help of social network, kinship, and sequence analysis, we empirically addressed the evolution of the Swiss patrician structure (Sarasin Reference Sarasin1998) at both the individual and the family levels.

Focusing on the long-term presence of the patriciate at the top of different local organizations and institutions, we observed a clear decline in the percentage of power positions occupied by patrician family members, however with significant differences across cities and social spheres. Interestingly, the overall decline in positional power does not systematically translate into a loss of kinship ties of patrician elite members with the positional elite. At the family level, we identified five groups of families according to their trajectories with respect to urban power positions and kinship ties. Some families, namely the Declining, disappear from the urban elite, while a few others named the Returnees (re-)appear. Three groups held their ground among the urban elite: the Fortified and the Established have developed kinship ties with patrician and non-patrician elites, whereas the Tieless embody an alternative to such kinship-based strategies.

Even tough, the traditional patrician structure of the late eighteenth century has declined in terms of wealth, accumulation of power positions, and kinship ties, our results show that alternative survival strategies exist. The Fortified and the Established highlight the persistence of strong homogamous matrimonial alliances and family co-optation – i.e., the transmission of elite positions within the family circle, as efficient mechanisms of power perpetuation. However, the Fortified tend to maintain conservative alliances with patrician families, while the Established have broader alliances outside the patriciate. The Tieless even manage to remain in power positions while not developing extended relationships with other elites (patrician or not). In other words, these results suggest that the decline of patrician families is not an “iron law” as suggested by Buddenbrooks-like explanations of business family decline. We cannot exclude that patrician families continue the remain influential through other means, as observed for instance by Rieder (Reference Rieder2008) for the city of Bern: despite a clear decline of their general influence, Bernese patrician families have remained very well organized in traditional local guilds and have maintained their influence on some aspects of urban governance.

Dynastic transmission of power – well into the twentieth century – is nothing which is specific to societies with old centralized monarchic rule and court societies (Elias Reference Elias1969; Lee and Park Reference Lee and Park2019). Even after the abolition of formal privileges in the nineteenth century, members of patrician families continued to hold positions of power, often relying on their embeddedness within kinship and family alliance networks. Our research contributes to the understanding of mechanisms that facilitate the survival of elites beyond the Swiss context. While the number of patricians in power positions declined during the first half of the twentieth century, this decline was relative. We do not observe a “decay” as defined by Cannadine (Reference Cannadine1990), as we are not examining a landowning class, but a power elite deeply rooted in urban settings. Although our definition of the urban elite does not rely on wealth but on the occupation of power positions, we find that Swiss patrician families adopt similar strategies as aristocratic and upper-class families by forming alliances primarily within their own ranks, as observed in other national contexts (Santiago-Caballero Reference Santiago-Caballero2021; Toft and Jarness Reference Toft and Jarness2021). Moreover, we note the significant role played by extensive and enduring family networks (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2023), which have been crucial for the longevity of these specific groups of families. However, the preservation of power by patrician families is not solely reliant on family alliances. Our findings also emphasize the importance of co-optation strategies, particularly within the economic realm, aligning with similar findings in the Netherlands and Austria (Dronkers and Schijf Reference Dronkers and Schijf2004; Korom and Dronkers Reference Korom, Dronkers, Kuiper, Bijleveld and Dronkers2015). In conclusion, the diverse strategies identified, varying across different spheres of power and cities, highlight the significance of examining local contexts to understand the intricate interplay between the decline and persistence of these families, recognizing that they do not constitute a homogeneous entity.

Three limitations to our study must be mentioned. First, we only observe families who held at least one power position from 1890 to 1957. Therefore, we cannot make a statement on all patrician families and our analysis is subject to some selection bias. This means that our results only apply to the patrician elites included in our sample of positional elites, thus we cannot generalize our observation for all patrician families. Second, our positional approach to the urban elite over seventy years cannot provide us information on the precise exercise of power and the concrete influence of the patrician elite. Third, and relatedly, our overview of the mechanisms of power preservation does not take into account that the patrician family members that do not hold any more power positions might exercise their influence by other means that are not related to the formal occupation of power positions.

Hence, our results open various research avenues. First, it seems necessary to carry out work on the more recent period, to understand to what extent the identified mechanisms apply even closer to the present day. Second, future research should analyze the changes in the profiles of patrician elites, notably in terms of educational credentials and international experience. Third, it is crucial to analyze the matrimonial alliances in more detail and, in particular, the preservation of the homogamy of the patrician elites as well as the overshadowed role of women in the persistence of the influence of patrician families.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was carried out as part of the project “Local Power Structures and Transnational Connections. New Perspectives on Elites in Switzerland, 1890-2020” and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant Number: CRSII5_183534). A previous version of this paper was presented at the 6th European Conference on Social Networks (EUSN), University of Greenwich, London, September 12–16, 2022. We would like to thank Damian Clavel, Matthieu Leimgruber, and Lucas Rappo for their very helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank the reviewers and editors for their careful evaluation and stimulating remarks.

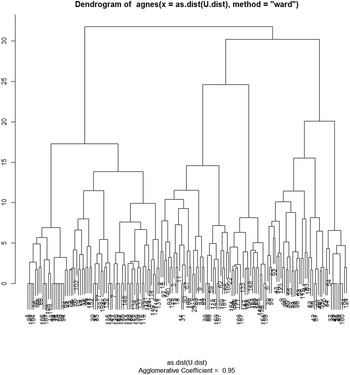

Appendix I. Dendrogram and silhouette for clustering the sequence analysis

A1. Dendrogram.

A2. Silhouette.

Appendix II. Number of power positions, regions, cities, and number of kinship ties according to each type of families’ trajectories

Modalities with a v-test equal to or greater than 2 (p-value <= 0.05) are displayed in bold when over-represented (Husson et al. Reference Husson, Lê and Pagès2017).