Introduction

There is a famous passage in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2003) where Harry and his friend Ron tell their friend Hermione (all in their puberty at this point in the saga) that they do not understand the behavior of Cho, who ran away in tears after kissing Harry. Hermione lays down her quill and proceeds to explain the emotional confusion of Cho who is grieving for the death of her former boyfriend, feels guilty for falling in love with Harry, fears social disapproval when becoming his girlfriend, and is also afraid of being thrown off the Ravenclaw Quidditch team because of weak performance. The boys are gobsmacked:

A slightly stunned silence greeted the end of this speech, then Ron said, “One person can’t feel all that at once, they’d explode.” “Just because you’ve got the emotional range of a teaspoon doesn’t mean we all have,” said Hermione nastily, picking up her quill again. (p. 406)

There is a parallel to be made with the recent explosion of interest in the emotions of foreign language (FL) learners. For many decades, research focused on a single negative emotion (anxiety) and only recently did the range expand when Dewaele and MacIntyre (Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) juxtaposed FL classroom anxiety (FLCA) with FL enjoyment (FLE) with the aim of understanding to what extent they were related to each other, and whether they were linked to similar learner-internal and learner-external variables.Footnote 1 The initial study and follow-up research of these two emotions provided plenty of evidence of complex dynamic interactions with a wide range of psychological, attitudinal, motivational, sociobiographical, and linguistic variables shaped by the classroom context, the school, and even the larger societal context (for overviews see Dewaele, Chen et al., Reference Dewaele, Chen, Padilla and Lake2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Derakhshan and Zhang2021). One crucial insight was just how messy and changeable the relationship between enjoyment and anxiety can be. The absence of one does not automatically imply the presence of the other and vice versa. Researchers soon pointed out that learners may experience other emotions such as FL boredom (FLB; Li et al., Reference Li, Dewaele and Hu2020; Pawlak et al., Reference Pawlak, Zawodniak and Kruk2020). The latest research in the field has started to include FLE, FLCA, and FLB in a single research design to find out how these three emotions jointly predict FL achievement and to what extent the three learner emotions are linked to the same or different learner-internal and learner-external variables (Li & Han, Reference Li and Han2022; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022).

This research is led by the belief that a better understanding of the complex emotions of FL learners can lead to improved pedagogical practices which in turn will boost performance and progress of FL learners. The current study follows this avenue of research and uses structural equation modeling, which allows researchers to explore complex relationships between different latent variables in one single model.

Literature review

The literature review is organized as follows: We start by sketching the current theoretical and epistemological foundation of the present study, dynamic system theory, which shaped our research questions, and report on a number of studies that adopted this framework. The next section defines the three emotions under investigation in the present study and presents the few studies that have included these emotions in a single research design. Next, we turn to studies that have linked teacher-related variables to learner emotions. This is followed by a section on the studies that investigated learner emotions and attitude/motivation after which we introduce a final section on the relationship between learner emotions and academic achievement. The literature review concludes with a theoretical justification for including FLE, FLCA, and FLB in a single research design.

The field of emotions in FL learning and teaching has been strongly affected by an influential paradigm shift in the last decade, namely complex dynamic systems theory (MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Henry, Dörnyei, MacIntyre and Henry2015). The default assumption of researchers working in this paradigm is that emotions that seem stable on a relatively long timescale (weeks, months, years) may in fact be fluctuating more strongly on shorter timescales (seconds, minutes, days) and that not all learners follow the average patterns for the group (Elahi Shirvan et al., Reference Elahi Shirvan, Taherian and Yazdanmehr2020, Reference Elahi Shirvan, Taherian and Yazdanmehr2021; Li, Reference Li2021). The second assumption is that dependent and independent variables are constantly interacting, shaped by the context and by variables lurking in the background. In other words, learner-internal variables interact with contextual variables resulting in unique patterns that change over time. A simple illustration of this phenomenon is the classroom observation of Denisa, a Romanian EFL participant in Dewaele and Pavelescu (Reference Dewaele and Pavelescu2021), who reported low FLCA, high FLE and who usually participated actively in class, except on the day the regular teacher was absent and a substitute teacher took the class. She reported later disliking the teacher, not enjoying the class, and preferring to remain silent throughout the class. What this suggests is that while how learners feel about their FL classes is partly determined by relatively longer-term dispositions linked to attitudes, motivation, and recent classroom experiences; by teacher behaviors; and by local, transient, and unpredictable factors that can lead to spikes or drops in FLE, FLCA, and FLB (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022a, Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022b).

FL Emotions: Definitions and interactions

The concept of foreign language enjoyment (FLE) as presented in Dewaele and MacIntyre (Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) draws on the theories of positive psychology, and more specifically on the work of Csíkszentmihályi (Reference Csíkszentmihályi1990). Dewaele and MacIntyre (Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, MacIntyre, Gregersen and Mercer2016) defined FLE as “a complex emotion, capturing interacting dimensions of challenge and perceived ability that reflect the human drive for success in the face of difficult tasks … enjoyment occurs when people not only meet their needs, but exceed them to accomplish something new or even unexpected” (pp. 216–17). In other words, enjoyment goes deeper than mere pleasure and it is less ephemeral. This definition situates FLE on a valence dimension, ranging from mid-way (low to mild enjoyment) to the top, positive end of the scale where FLE becomes an experience of flow. It is worth pointing out that the authors did not add any information about the separate dimension of arousal/activation. They assumed that FLE could emerge in medium-arousal activities such as silent reading or writing, as well as in high-arousal situations such as debates in the classroom or public speech.

The second emotion to be included in Dewaele and MacIntyre’s (Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) design was foreign language classroom anxiety (FLCA) that was defined by Horwitz et al. (Reference Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope1986) as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (p. 128). MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017) pointed out that FLCA is both an internal state and a social construct. In other words, it combines learner-internal and learner-external elements resulting in complex “internal psychological processes, cognition and emotional states along with the demands of the situation and the presence of other people” (p. 28). Horwitz (Reference Horwitz, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017) argued that FLCA has characteristics of both traits and states: FLCA does not exist at birth but it can slowly emerge and strengthen among learners who tend to be anxious in the FL class, it can coalesce into statelike FLCA that rears its head every time the FL has to be used. Reflecting on the causes of FLCA, Horwitz (Reference Horwitz, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017) pointed to the fact that FL learners can experience a profound feeling of discomfort because they lack the proficiency to present themselves authentically, something they typically have no problem doing in their first language. Indeed, “presenting yourself to the world through an imperfectly controlled new language is inherently anxiety-provoking for some people” (p. 44). High levels of FLCA can be manifested by physical symptoms (sweating, quicker heart rate, dry mouth) that can leave learners paralyzed and silent, disrupt concentration, which limits absorption of new information (MacIntyre & Gregersen, Reference MacIntyre and Gregersen2012).

The third classroom emotion to have attracted increasing attention recently is FL boredom (FLB). In most cases, boredom is an unpleasant psychological and emotional state that combines feelings of “dissatisfaction, disappointment, annoyance, inattention, lack of motivation to pursue previously set goals and impaired vitality” (Kruk & Zawodniak, Reference Kruk, Zawodniak, Szymański, Zawodniak, Łobodziec and Smoluk2018, p. 177). Li et al. (Reference Li, Dewaele and Hu2020) defined FLB as “a negative emotion with extremely low degree of activation/arousal that arises from ongoing activities … [that] are typically over-challenging or under-challenging” (p. 12).Footnote 2

As emotions are hypothesized to interact in an academic setting, the current research interest is not only to examine the three emotion variables of FLE, FLCA, and FLB in isolation but also to examine the relationships between these variables. As such, studies examining the relationships and interaction between emotion variables in the FL class become increasingly popular. In the study introducing FLE to the applied linguistics lexicon, Dewaele and MacIntyre (Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) compared and contrasted FLE and FLCA. They found a statistically significant negative correlation between the two emotion variables, which has since been confirmed in a recent meta-analysis of k = 47 studies (r = –.32; Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2022). Li and Han (Reference Li and Han2022) was the first study (published in Chinese) to include FLE, FLCA, and FLB in a single research design. The authors found significant negative correlations between Chinese EFL students’ FLE and FLCA, between FLE and FLB, and a significant positive correlation between FLCA and FLB. Broadly similar patterns emerged in Li and Wei (Reference Li and Wei2022) with a significant negative correlation between FLE and FLB and a significant positive correlation between FLCA and FLB. However, no correlation was found between FLE and FLCA. As such, we include the following hypothesis in our study:

Hypothesis 1: There are statistically significant correlational effects between the emotion variables of FLE, FLCA, and FLB.

FL emotions and teacher-related variables

Teacher behaviors as predictors of learner emotions in the classroom have been extensively studied in general educational settings and mathematics learning, with teacher behavior such as enthusiasm, understandability, support, comprehensibility, and pace linked to positively to positive academic emotions such as joy and negatively to negative emotions such as anxiety and boredom (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Goetz, Morger and Ranellucci2014; Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Lüdtke, Nett, Keller and Lipnevich2013; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Cui and Chiu2018). In the specific domain of FL learning, teacher behavior has also been found to predict FLE, FLCA, and FLB.

The first study to focus on the effect of teacher characteristics on FLE was Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018). The authors found that the pupils from two secondary schools in London with the highest level of FLE reported more positive attitudes toward the FL and the FL teacher. More specifically, pupils liked teachers who used the FL frequently in class, who were unpredictable, and who gave students the opportunity to speak up. A follow-up study by Dewaele and Dewaele (Reference Dewaele and Dewaele2020) on a subsample of pupils in the same database who had two different teachers for the same FL revealed that FLE was significantly higher with the main teacher than with the second teacher and that scores for attitude toward the teacher, teacher’s frequency of use of the FL in class, and unpredictability were significantly higher for the former. The pattern was confirmed in Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019) who found that teachers’ characteristics predicted twice the amount of variance in FLE than in FLCA among Spanish EFL learners. The teacher’s friendliness and skill emerged as the strongest predictors of FLE. A broadly similar pattern emerged among Chinese undergraduate EFL learners in Jiang and Dewaele (Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019). Attitudes toward the teacher, teacher’s joking, and friendliness—but not teachers’ un/predictability were strong predictors of FLE. This was backed up by students’ narratives that mentioned the teacher more frequently when discussing FLE compared to FLCA, confirming previous research on an international sample of FL learners (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, Sato and Loewen2019). Jiang (Reference Jiang2020) pursued this path using the focused essay technique with Chinese EFL students. She found that FLE was positively related with teacher friendliness, patience, kindness, happiness, and regular use of humor. Similarly, Elahi Shirvan et al. (Reference Elahi Shirvan, Taherian and Yazdanmehr2020) found that the teacher was the typical cause of spikes in FLE among individual learners by giving positive feedback, using humor and creating a pleasant and supportive classroom atmosphere. Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022a), in a study n = 360 FL learners of English, German, French, and Spanish in a Kuwaiti university, investigated the changing effect of teachers’ frequency of using the FL in class, predictability and frequency of joking on FLE, FLCA and attitudes/motivation. Mixed-effects regression analyses on FLE revealed significant main effects of all three teacher behaviors (R2 = 26.2%). A post-hoc analyses on the significant interaction effect of time and frequency of joking revealed that students whose teacher joked infrequently reported the sharpest drop in FLE over the semester. The unexpected finding of a positive relationship between FLE and teacher predictability was attributed to the specific cultural-religious profile of the learners.

In turn, FLCA has also been linked to a range of learner-external variables such as the emotional atmosphere in the FL classroom (Effiong, Reference Effiong2016); the strictness, the younger age, and the lower use of the FL by the teacher (Dewaele, Franco Magdalena et al., Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019); the target language and its perception in the school community (De Smet et al., Reference De Smet, Mettewie, Galand, Hiligsmann and Van Mensel2018); and the modality of teaching (online or “in person”; Li & Dewaele, Reference Li and Dewaele2021; Resnik & Dewaele, Reference Resnik and Dewaele2021; Resnik et al., Reference Resnik, Dewaele and Knechtelsdorfer2022). Although it should be noted that several studies have compared and contrasted the effects of teacher-behaviors on both FLCA and FLE and found that teacher-related variables were more closely associated with FLE than with FLCA (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019; Dewaele, Franco Magdalena et al., Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018).

Similarly, teacher-related variables have been linked to FLB. Li (Reference Li2021) found that different control–value appraisals predicted FLB uniquely or interactively and that different types of appraisals occurred simultaneously and interacted in predicting FLB. Intrinsic value appraisal turned out to be a much stronger predictor of FLB than control and extrinsic value appraisals. Learners who felt competent (high control) and valued their English classes (reflecting higher engagement) tended to feel less bored. This finding was confirmed by interviews with students. Analysis of the qualitative data revealed a curvilinear relationship between control appraisal and FLB: “[E]xtremely high and low control were both antecedents of boredom. In other words, students got bored when they felt overwhelmingly challenged or underchallenged in English learning” (p. 329). Analysis of the qualitative data also showed that intrinsic value protected learners in boredom-inducing situations. Li (Reference Li2021) concludes that to avoid FLB in their classrooms, teachers should design tasks at the appropriate level of difficulty to boost learners’ sense of confidence, competence, and control, while emphasizing the intrinsic value of the activity. Creating a positive emotional classroom atmosphere is also a prerequisite for more FLE, less FLCA, and an alleviation of FLB. The importance of the teacher was further highlighted in Dewaele and Li (Reference Dewaele and Li2021) where mediation analysis showed that teacher enthusiasm strongly affected the learning engagement of Chinese EFL learners. It had both a direct and an indirect effect on both FLE and FLB, which were linked to teacher enthusiasm, positively for FLE, and negatively for FLB. Moreover, FLE and FLB were found to mediate the effect of participants’ perceived teacher enthusiasm on their own engagement (positive for FLE and negative for FLB).

As such, we therefore propose the following hypotheses to explore the relationship between the FL emotions and teacher-related variables:

Hypothesis 2: Teacher FL use will have a direct effect on FLE, FLCA, and FLB.

Hypothesis 3: Teacher unpredictability will have a direct effect on FLE, FLCA, and FLB.

FL emotions and attitude/motivation

Classroom emotions has been found to affect a learner’s attitude and motivation to study science (Sinatra et al., Reference Sinatra, Broughton, Lombardi, Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia2014), physical education (Simonton & Garn, Reference Simonton and Garn2019), medicine and nursing studies (Artino et al., Reference Artino, Holmboe and Durning2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Na, Kim, Kim, Park and Choi2021), and mathematics (Goldin, Reference Goldin, Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia2014). It is therefore not unexpected that emotions in the FL classroom has been found to affect attitudinal and motivational variables. Previous research has found positive relationships between FLE and attitude toward the FL (De Smet et al., Reference De Smet, Mettewie, Galand, Hiligsmann and Van Mensel2018; Dewaele and Dewaele, Reference Dewaele and Dewaele2017; Dewaele, Özdemir et al., Reference Dewaele, Özdemir, Karci, Uysal, Özdemir and Balta2022; Jiang and Dewaele, Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019) as well as motivation to learn (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dai and Wang2020). In contrast, FLCA has been negatively associated with the attitude toward the FL (Dewaele & Proietti Ergün, Reference Dewaele and Proietti Ergün2020) and a general motivation to learn the target language (Liu & Cheng, Reference Liu and Cheng2014; Liu & Huang, Reference Liu and Huang2011; Neisi & Yamini, Reference Neisi and Yamini2009). Although research regarding motivation and FLB has received less attention, most probably due to the relative recency of the variable, some initial recent findings have reported a negative relationship between FLB and motivation to learn the FL (Kruk, Reference Kruk2016, Reference Kruk2022; Pawlak et al., Reference Pawlak, Zawodniak and Kruk2021). As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: FLE, FLCA, and FLB will have a direct effect on the attitude of the FL learner toward the FL.

FL emotions and academic achievement

As the overarching goal of FL learning is undoubtedly the acquisition of the target language, the question has to be asked whether FL emotions can affect the actual learning of a language? Previous research has utilized proxy variables to capture FL learning as an outcome variable, with academic achievement in the form of grades or exam scores, or self-perceived levels of proficiency or competency being used in the majority of studies (see Teimouri et al., Reference Teimouri, Goetze and Plonsky2019). All three emotion variables of FLE, FLCA, and FLB have been linked directly, and indirectly, to real and perceived achievement in the FL class.

Several studies reported significant positive relationships between FLE and both actual and perceived FL proficiency measures (Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2020a; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018; Dewaele & Proietti Ergün, Reference Dewaele and Proietti Ergün2020; Li, Reference Li2020; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022; Piechurska-Kuciel, Reference Piechurska-Kuciel, Gabryś-Barker, Gałajda, Wojtaszek and Zakrajewski2017; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Gao and Wang2019; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Dai and Wang2020). A meta-analysis of studies that linked FLE and academic achievement in the FL revealed moderate positive correlations between FLE and academic achievement (r = .30, k = 28, N = 8,883), and between FLE and self-perceived achievement (r = .27, k = 9, N = 4,810; Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2022). In other words, learners with higher levels FLE are more likely to have higher levels of academic achievement as well as a greater perception of their own abilities.

In turn, FLCA has been found to negatively affect learners’ performance and can be “highly detrimental to the learning process” (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017, p. 150). Meta-analytic studies have revealed comparable negative correlations between FLCA and a range of measures of academic FL performance (r = –.39; k = 59; N = 12585; Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2020b). Similarly to FLCA, FLB has been linked to lower levels of academic achievement, as well as lower levels of perceived achievement (Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022; Li et al., Reference Li, Huang and Li2021; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Pekrun, Marsh and Loderer2020). Thus, learners with higher levels FLCA and FLB, are less likely to have greater levels of academic achievement.

Although studies examining the relationship between FLE, FLCA, and FLB, and academic achievement individually are relatively popular, studies examining all three emotions in a single design are less so. Li and Han (Reference Li and Han2022) were the first to examine the relationship between FLE, FLCA, and FLB, and real and perceived achievement. FLE was found to have independent positive predictive effects on actual English test scores and perceived learning achievement, while FLB and FLCA had negative predictive effects. However, a regression analysis revealed that FLCA was the only significant predictor for test scores, whereas FLE and FLB predicted perceived achievement. In addition, Li and Wei (Reference Li and Wei2022) examined the effect over time of FLE, FLCA, and FLB on the EFL achievement of n = 954 junior secondary learners in rural China. Structural equation modeling results showed that the three emotions that learners experienced at Time 1 predicted their English achievement at Time 2 but that FLE was the strongest and most enduring predictor (in contrast to the result of Li and Han [2022]), with FLCA being a negative predictor at Time 2 and Time 3, while the negative effect of FLB faded completely over time.

As such, contrasting results have emerged in studies in which all three emotion variables are included in a single study design and are hypothesized to affect learning outcomes—as opposed to the research consensus when these emotion variables are hypothesized to affect learning in isolation. We therefore include the following research questions and hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5: FLE, FLCA, and FLB will have a direct effect on the academic achievement of the FL learner.

Hypothesis 6: The attitude toward the FL will have a direct effect on the academic achievement of the FL learner.

Choice of the learner emotions

The decision to include FLE, FLCA, and FLB in the research design is based on theoretical considerations (Dewaele & Li, Reference Dewaele and Li2021; Li, Reference Li2021; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022). The Control-Value Theory (CVT) of achievement emotions (Pekrun, Reference Pekrun2006) has provided applied linguists with a solid theoretical basis for research into learners’ emotions. Pekrun and Stephens (Reference Pekrun and Stephens2010) suggested that achievement emotions can be organized along three dimensions: (1) object focus (the activity vs. the outcome), (2) valence (positive vs. negative), and (3) activation (deactivation vs. activation). FLE, FLCA, and FLB occupy unique positions on these three dimensions. FLE and FLB are activity-related achievement emotions that arise from ongoing activities but stand at opposite ends of the valence and activation dimensions: FLE is a positive activating emotion, while FLB is a negative deactivating emotion. FLCA, however, is an outcome-related achievement emotion evoked by past outcomes of FL learning activities and is a negative, activating emotion (Pekrun & Perry, Reference Pekrun, Perry, Pekrun and Linnenbrink–Garcia2014). In other words, the inclusion of these three emotions in the research design allows a unique three-dimensional perspective on their causes and effects.

In summary, considering the literature review, we formulated the following research questions:

-

RQ 1. What are the relationships between FLE, FLCA, and FLB?

-

RQ 2. What is the effect of teacher FL use on FLE, FLCA, and FLB?

-

RQ 3. What is the effect of teacher unpredictability on FLE, FLCA, and FLB?

-

RQ 4. What is the effect of FLE, FLCA, and FLB on attitude of the FL learner toward the FL?

-

RQ 5. What is the effect of FLE, FLCA, and FLB on academic achievement of the FL learner?

-

RQ 6. What is the effect of attitude toward the FL on academic achievement of the FL learner?

We hypothesize that FLE, FLCA, and FLB are independent dimensions that they are linked with each other to various degrees. We also hypothesize that FL learners’ attitude toward the FL, teacher unpredictability and frequency of FL use in the classroom are linked to FLE, FLCA, and FLB. These three FL emotions are hypothesized, in turn, to predict achievement in the FL directly and indirectly.

Method

Participants

Data were collected through snowball sampling, which is a form of nonprobability sampling (Ness Evans & Rooney, Reference Ness Evans and Rooney2013). An open-access anonymous online questionnaire was used. Calls for participation were sent through emails to colleagues, students, and friends all over the world, asking them to forward the link to their own colleagues and students. The call for participation was also put on social media platforms used by FL teachers. The questionnaire was anonymous. The research design and questionnaire obtained approval from the ethics committee in the first author’s research institution. Participants’ consent was obtained at the start of the survey that was posted online using Google Docs.

A total of 332 FL learners filled out the questionnaire completely. The average age of the sample was 25.46 (SD = 12.08), with the majority learning an FL in a university course (n = 235), followed by a secondary school class (n = 97). The sample contained 252 female participants and 73 male participants. The gender imbalance in the data was not unexpected as it has often been observed in previous FL learning research (see Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014). The sample was highly diverse in terms of nationality, multilingualism, and target FL. The majority of participants were British nationals (n = 95), followed by Chinese (n = 47) and Italians (n = 27). The average number of languages in each participant’s linguistic repertoire was 3.14 (SD = 1.25). English was the most reported target FL (n = 116), followed by French (n = 85), and Spanish (n = 44).

Instruments

The following instruments were used to measure variables in this exploratory study:

Short-form foreign language classroom anxiety scale (ω = .884; α = .893)

An eight-item measure designed by MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre1992) that examines FL anxiety in the FL classroom with items such as “I get nervous and confused when I am speaking in my language class.” The measure is unidimensional with all items loading on a single FLCA latent variable. Items were measured on a five-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Short-form foreign language enjoyment scale (ω = .895; α = .875)

The nine-item scale was designed by Botes et al. (Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2021) and is a shortened version of the original 21-item scale (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014). The underlying factor structure of the scale contains one higher-order FLE factor and three lower-order factors, namely personal enjoyment (three items, e.g., “I enjoy my FL class”), social enjoyment (three items, e.g., “There is a good atmosphere in my FL classroom”), and teacher appreciation (3 items, e.g., “My FL teacher is encouraging”). Items were measured on a five-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Foreign Language Classroom Boredom Scale (ω = .944; α = .943)

An eight-item scale aimed at examining FL boredom within a FL classroom setting, with items such as “My mind begins to wander in FL class” and “It is difficult for me to concentrate in the FL class” (Li et al., Reference Li, Dewaele and Hu2020). It should be noted that the eight-item measure is originally a subscale of the greater 32-item Foreign Language Boredom Scale (ibid.). However, as the emotion variables in this exploratory study are contextualized as specific to FL learning class, the decision was made to only utilize the FL classroom boredom subscale and not the scale in its entirety. Items were measured on a five-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

FL attitude

Attitude toward the target FL was measured by a single item asking the participants: “What is your attitude toward your FL?.” Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “very unfavorable” to “very favorable.”

FL academic achievement

Achievement was measured through a single item asking FL learners to provide the last mark received for a test/exam in their FL class in percentage.

Teacher FL use

The frequency of FL use by the teacher in the FL classroom was measured through a single item asking participants: “How often does your teacher use the FL in class?” The item was measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “hardly ever” to “all the time.”

FL teacher predictability

The predictability of the FL teacher was measured through one single question: “How predictable are your FL teacher’s classes?” Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “very unpredictable” to “very predictable.”

Data analysis

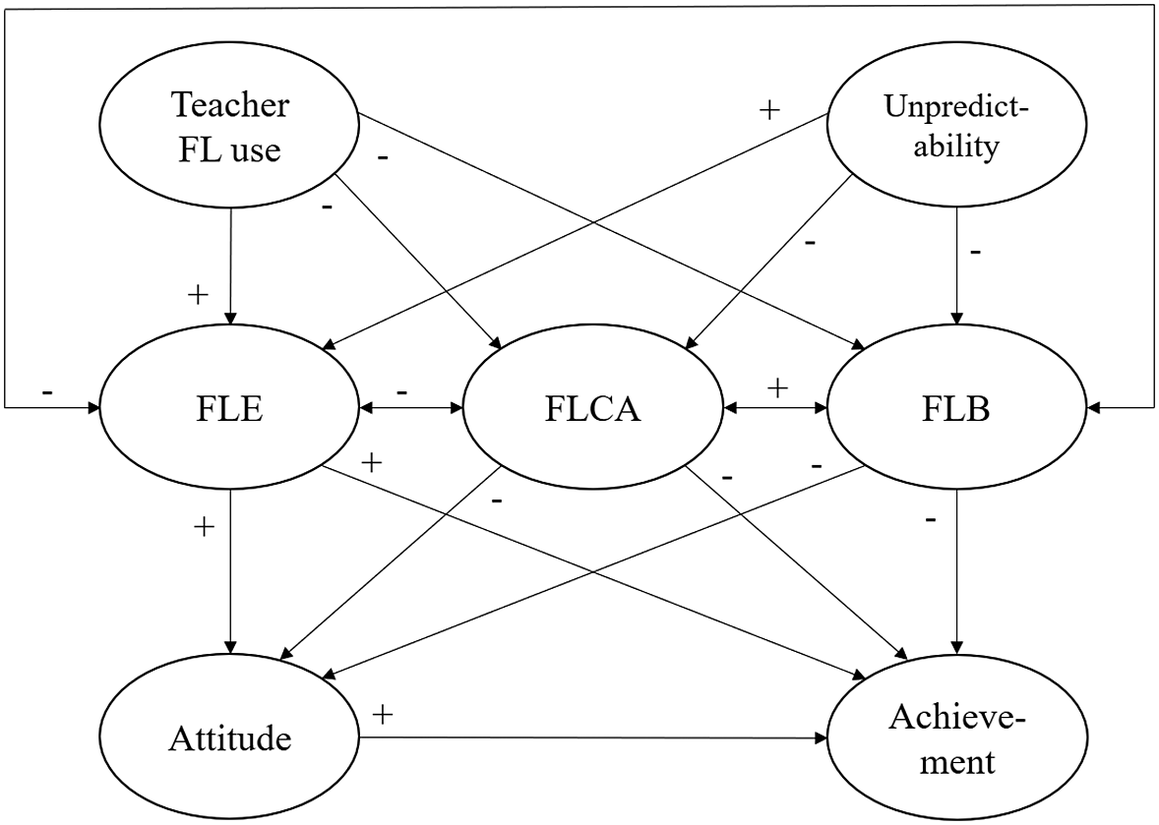

Descriptive statistics and correlations between all variables were calculated in SPSS 25.0. An exploratory SEM was tested in JASP (version 0.11.1; JASP Team, 2020), utilizing Lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012). The exploratory SEM was developed based on the prevailing literature and hypotheses (see Figure 1). SEM was chosen as the method to examine the data above the use of multiple regression or simple correlations, as the method allowed for the latent modeling of variables with measurement error taken into account (Ullman & Bentler, Reference Ullman and Bentler2012). As such, the three emotion variables specifically could be explored in terms of the greater nomological network of teacher and outcome variables (Figure 1), with unbiased estimates and as such providing a clearer picture of the relationships between variables (ibid.). Furthermore, SEM provides indicators for model fit and modification indices, which are invaluable in confirming the exploratory research questions of this study.

Figure 1. Proposed structural equation model.

It should be noted that as four variables were measured by only a single item (FL attitude, FL achievement, teacher FL use, teacher predictability), these variables had to be specified as latent in the model by constraining factor loadings and error variances (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Reference Fuchs and Diamantopoulos2009). The use of single indicator variables has often been avoided in past SEM research, as “the use of single-item measures in academic research is often considered a fatal error in the review process” (Wanous et al., Reference Wanous, Reichers and Hudy1997, p. 247). However, single-item measures can be a valid, psychometrically sound alternative to multiitem measures (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Reference Fuchs and Diamantopoulos2009; Petrescu, Reference Petrescu2013). Accordingly, several benefits can be provided by single-item measures such as flexibility, brevity, providing a global score, and the possibility of measuring a greater number of variables without overburdening the participant (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Reference Fuchs and Diamantopoulos2009). As the current study examines seven distinct variables, three of which were measured through multiitem psychometrically validated measures (FLE, FLCA, and FLB), the decision was made to measure the remaining four items through single-item measures. We are fully cognizant of the possible drawbacks of single-item measures, however the decision allowed for a greater number of variables to be included in the exploratory study and as such widen the nomological network under investigation.

The model was tested utilizing maximum likelihood estimation with robust error. Model fit was primarily analyzed through the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Cutoff recommendations set by Kenny (Reference Kenny2020) were used to determine fit, with the RMSEA and SRMR indicating close fit if less than the rule-of-thumb value of .08. In turn, CFI and TLI indicate close fit when greater than .90. In addition, the chi-square (χ2) and chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) were also considered in the estimation of fit. A nonsignificant chi-square and a chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio of < 2.0 were used to indicate close fit (Byrne, Reference Byrne1998).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients

Descriptive statistics for all variables included in the model can be found in Table 1. In addition, a Pearson correlation coefficient matrix of all variables is displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2. Correlation coefficient matrix

*** p < .001; **p < .01.

Structural equation modeling

The model achieved close fit as indicated by the RMSEA (.068) and SRMR (.057), which were both below the cutoff of .08 (Kenny, Reference Kenny2020). In addition, the CFI (.933) and TLI (.921) were both above the minimum limit of .90 (ibid.), further indicating close fit. In contrast, the chi-square was significant (χ2 (217) = 549.99; p < .001), with a χ2/df ratio (2.52) of >2.0, implying poor fit (Byrne, Reference Byrne1998). However, the chi-square has been found to be particularly sensitive to sample size and large correlations between factors, which may result in Type 1 errors (Kenny, Reference Kenny2020). As such, the bulk of fit indices indicated close fit and the model is therefore accepted as an adequate representation of the data.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, a number of hypothesized paths in the model were statistically insignificant (see Table 3 for overview of hypotheses). This is not an unexpected result given the exploratory nature of this study. However, support was found for the first hypothesis of the study as there were statistically significant symmetrical effects between all emotion variables. FLE was found to be negatively correlated with both FLCA (r = –.303; p < .001) and FLB (r = –.500; p < .001). In addition, FLCA and FLB shared a statistically significant positive correlation (r = .451; p < .001). The emotion variables of FLE, FLCA, and FLB are therefore interdependent in the FL classroom.

Figure 2. Structural equation modeling result.

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Table 3. Hypotheses overview

The second hypothesis was partially substantiated in the structural equation model. Teacher FL use had a significant positive effect on FLE (β = .133; p < .01). However, no statistically significant effect was found between teacher FL use and the two negative emotion variables of FLCA and FLB (p > .05). The use of the target FL in the FL classroom therefore only seems to impact the positive emotion of enjoyment and has no effect on either anxiety or boredom in the FL learning context.

The third hypothesis of teacher un/predictability influencing the three emotion variables was also partially substantiated. Teacher unpredictability had a significant positive effect on FLE (β = .119; p < .05) and a significant negative effect on FLB (β = .199; p < .01). No statistically significant effect was found between teacher unpredictability and FLCA (p > .05). As such, the results of both the first and second hypotheses seem to indicate that teacher-related variables may be more related to positive emotion (e.g., FLE) than to negative emotion (e.g., FLCA).

Similarly, partial evidence was found to support the fourth hypothesis. The two variables of FLE and FLB both predicted the attitude of the FL learners, with no statistically significant relationship found between FLCA and FL attitude. FLE positively influenced the FL learner’s attitude toward their target FL (β = .134; p < .01), while FLB negatively influenced FL learner’s target FL attitude (β = –.268; p < .01).

In contrast to the findings of the fourth hypothesis, the only statistically significant path found between the emotion variables and academic achievement was in the impact of FLCA on academic achievement (β = –.145; p < .01). Neither FLE nor FLB had a statistically significant effect on academic achievement in the FL. The fifth hypothesis was therefore only partially supported. Lastly, the results indicated support for the sixth hypothesis that FL attitude positively influence academic achievement (β = .141; p < .01).

Overall, the proposed model was found to closely fit the data and support was found for the majority of hypothesized relationships. The model indicated a complex nomological network, with the three emotions of FLE, FLCA, and FLB, each having unique associations with the teacher-related variables and the outcome variables of FL attitude and academic achievement.

Discussion

The aim of the present article was to throw a wide net to link three FL learner emotions with a number of learner-internal and learner-external variables to explore how they are connected to each other. In doing so, we wanted to present a wide panoramic view of the range of activating and deactivating positive and negative FL learner emotions, their sources, and their effects. SEM allowed us to uncover the multiple relations between the variables in our dataset. Our first hypothesis was confirmed as we did find significant correlations between the three emotions: FL learners who enjoyed themselves were less anxious and less bored than those who reported lower levels of FLE. Also, more anxious FL learners suffered more from boredom, which could be linked to a lack of control and lower engagement causing these negative emotions (Li, Reference Li2021). This finding confirms and extends the findings about the moderate negative relationship between FLE and FLCA first reported in Dewaele & MacIntyre (Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) and confirmed in ulterior studies on different FL populations (Jiang & Dewaele, Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019; Li & Han, Reference Li and Han2022)—although not in Li and Wei (Reference Li and Wei2022). It could be interpreted in two ways: One could either argue that high FLE helps learners neutralize the negative effects of FLCA or, alternatively, that high FLCA chips away at the FLE, possibly because of the distracting and tiring effects of anxiety. The negative relationship between FLE and FLB makes perfect sense: A bored student is by definition not much engaged in the classroom activities and cursing how slowly the clock ticks (Li, Reference Li2021; Li & Dewaele, Reference Li and Dewaele2021; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022; Li et al. Reference Li, Huang and Li2021).

The second research hypothesis focused on the role of teacher’s frequency of use of the FL in shaping learners’ emotions. We hypothesized that frequent FL use would boost FLE and reduce FLCA and FLB. While the first part of that hypothesis was confirmed, namely frequent use of the FL by the teacher had a significant positive effect on FLE, confirming previous research (Dewaele & Dewaele, Reference Dewaele and Dewaele2017; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018; Dewaele, Franco Magdalena et al. Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019; Jiang & Dewaele, Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019), the second and third part of the hypothesis were rejected as no statistically significant link was found between frequency of teacher FL use and FLCA and FLB. In other words, learners’ FLCA and FLB were not neutralized by increased use of the FL by the teacher. The third hypothesis focused on the effect of teacher unpredictability on FLE, FLCA, and FLB. Teacher unpredictability was found to affect two out of the three learner emotions, which partly confirmed our hypothesis. FL learners reported significantly higher levels of FLE and lower levels of FLB with teachers who did not stick to the same routines in their class and varied in the way they taught the class. This finding confirms earlier studies on Western learners (Dewaele & Dewaele, Reference Dewaele and Dewaele2017; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018, Dewaele, Franco Magdalena et al. Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019), partly contradicts the study on Chinese learners where little effect was found (Jiang & Dewaele, Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019; Li et al., Reference Lei, Cui and Chiu2018), and completely contradicts the finding of the study on Arabic learners where the opposite pattern emerged, namely more predictability of the teacher being linked to higher enjoyment (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022a). Teacher unpredictability had no effect on FLCA, which confirms previous research (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, Sato and Loewen2019; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022a).

The relationship between attitude of the FL learner toward the FL, FLE, FLCA, and FLB constituted the fourth hypothesis. The hypothesis that classroom emotions would predict attitudes toward the FL was partly confirmed. Students who enjoyed themselves and were not bored in the FL class had a much positive attitude toward the FL. FLCA had no effect, which again confirms previous research on FLE and FLCA (Dewaele & Dewaele, Reference Dewaele and Dewaele2017; Dewaele et al. Reference Dewaele, Franco Magdalena and Saito2019; Li & Dewaele, Reference Li and Dewaele2021), but it contradicts the finding that attitude toward the FL was negatively linked to FLCA in Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018) and Jiang and Dewaele (Reference Jiang and Dewaele2019). As Botes et al. (Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2020a) emphasized, we cannot exclude the possibility that the causal relationship between emotions and attitudes could also go the other way: Learners with a more positive attitude toward the FL are more likely to feel happy and excited in the FL class, which may, in turn, strengthen their positive attitude toward the language and the culture.

The fifth and sixth hypotheses delved into the relationships between FLE, FLCA, FLB, attitude toward the FL and achievement. Partial support emerged for the fifth hypothesis as it turned out that only FLCA had a (negative) effect on academic achievement. This effect is well documented (Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2020b; Dewaele & Proietti Ergün, Reference Dewaele and Proietti Ergün2020; Dewaele & Li, Reference Dewaele and Li2022; Li & Han, Reference Li and Han2022; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022), however, most studies also reported a (typically slightly weaker) positive effect of FLE on achievement (Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2020a, Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2022; Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018; Li, Reference Li2020; Piechurska-Kuciel, Reference Piechurska-Kuciel, Gabryś-Barker, Gałajda, Wojtaszek and Zakrajewski2017; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Gao and Wang2019) except in Dewaele and Alfawzan (Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018) and in Li and Wei (Reference Li and Wei2022) where FLE was “the strongest and most enduring predictor” of FL achievement (p. 1) while the negative effect of FLB weakened over time. The finding in Li and Han (Reference Li and Han2022) that FLE and FLB predicted perceived achievement rather than actual achievement suggests a partial mismatch between the vision that learners have of their own performance and their actual performance. The sixth hypothesis about a positive link between attitude toward the FL and FL achievement was confirmed, echoing previous research (Dewaele & Proietti Ergün, Reference Dewaele and Proietti Ergün2020), where the effect was found to be stronger for the weaker FL (Italian) than for the stronger FL (English). This confirms that increased interest in the FL and in the culture can boost learners’ effort to perform well (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Witney, Saito and Dewaele2018, 2019).

The present study is not without limitations. Firstly, the sample included a wide variety of participants from across the world. Context-specific effects could therefore not be demonstrated, such as the impact of culture, age, and target FL. Secondly, several variables were measured utilizing a single item. Although the use of single-item variables in SEM is an accepted practice (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Reference Fuchs and Diamantopoulos2009), a model with multiple indicators does provide greater psychometric confidence. We do believe that the inclusion of all variables did provide a more panoramic view of complex interactions between multiple variables that have not all been brought together in previous research designs. Lastly, we acknowledge that other independent variables that were not included in the current study for reasons of economy may also contribute to the relationships we observed. It is very likely that frequency of teacher joking, teacher enthusiasm, and classroom environment triggered a process of positive emotional contagion which boosted learners’ positive emotions and engagement, and subsequent achievement (cf. Dewaele & Li, Reference Dewaele and Li2021; Dewaele et al. Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022a, Reference Dewaele, Saito and Halimi2022b; Li & Wei, Reference Li and Wei2022). One way to find out what these variables are would be through an alternative emic, qualitative approach. Semistructured interviews with FL learners could throw light on what goes on in their head when their teacher is unpredictable again in class or asks them something in the FL that they do not quite understand, what they feel about the FL and the culture, or how they manage to impose order in their mind and focus when doing FL tests or exams. An alternative approach is the use of diary studies to understand how and why learners’ emotions fluctuation. Additionally, writing about their emotions may encourage learners to reflect on them, which could enable them to regulate them more effectively (Zawodniak et al., Reference Zawodniak, Kruk and Pawlak2021). Finally, it is very likely that the shape and texture of FLE, FLCA, and FLB was affected by co-occurring feelings and emotions such as hope, optimism, shame, and guilt (Dewaele & Pavelescu, Reference Dewaele and Pavelescu2021).

It is not self-evident whether specific pedagogical implications can be drawn from this exploratory work. The network of relationships identified in the present study cannot be translated into specific actions teachers can take to boost students’ FL achievement. Only intervention studies can test the effect of specific teaching strategies, which would be great opportunity for further research. Yet, a number of rather broad recommendations can be drawn from the findings. A degree of unpredictability in the FL class, combined with abundant use of the FL seem to boost FLE and lower FLB without affecting FLCA. Awakening students’ interest in the FL and culture and thus shaping their attitude toward the FL can have both direct and indirect beneficial effects on their achievement. Attempts to alleviate FLCA in testing and examinations may have a positive effect on results. In short, creating a rich, exciting, positive emotional classroom atmosphere will shape FL learner emotions in ways that will allow them to grow and thrive (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, MacIntyre, Gregersen and Mercer2016; Elahi Shirvan et al., Reference Elahi Shirvan, Taherian and Yazdanmehr2021; Li, Reference Li2021).

Conclusion

We started the introduction with a reference to J. K. Rowling’s fictional character Ron Weasley who could not quite believe that a person could experience many different emotions simultaneously without their head exploding. We linked this to the field of FL learner emotions where the emotional range was larger than a teaspoon because researchers had been investigating FLCA for several decades, but where the emotional range only increased with the appearance of other emotions, such as boredom, shame, curiosity, pride, or hope. By including FLB in the current research design, a deactivating emotion—in addition to FLE and FLCA, which are positive and negative activating emotions—we extended the range of emotions in terms of valence and activation. With the further inclusion of a number of learner-internal and learner-external variables, the present study stretches the range by exploring relationships between three FL learner emotions, their sources, and their effects. The findings suggest that FLE, FLCA, and FLB are interconnected and are differentially shaped by a learner-internal variable (attitude toward the FL) and by teacher behaviors such as frequency of use of the FL in class and unpredictability, which in turn determines learners’ achievement.

To conclude, researchers, like the characters in the Harry Potter books, need to stretch the epistemological and methodological boundaries to gain knowledge and wisdom. It does not require magic, although FL learners in a state of flow may think their teacher possesses magical powers.

Funding information

Supported by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) (PRIDE/15/10921377).