Volume 222 - Issue 4 - April 2023

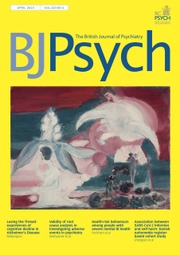

Else Blankenhorn, Self Portrait with Emperor Wilhelm II. as a Swan

1908–1919 | Oil on gray cardboard | 27.5 x 35.3 cm | Inv.No. 4300

© Prinzhorn Collection, Heidelberg University Hospital

As a private patient of the renowned Swiss Bellevue Sanatorium, Else Blankenhorn (1873–1920) was extremely privileged. Born in Karlsruhe, the daughter of a professor of viticulture, she made music, composed, photographed, wrote, translated, knitted, and embroidered before she also began to draw and paint at the institution in 1908. She developed an expressive visual language with simplified forms, energetic brushwork, and strong colour contrasts. Many of her pictorial motifs are symbolically charged and difficult to decipher. Blankenhorn believed she was married to Kaiser Wilhelm II, her “husband in spirit”. As Empress Else, she produced bank bills in fantastic sums to finance the resurrection of buried couples. In a self-portrait in oil, she depicted herself with the emperor, recognizable by his characteristic moustache, in a floral landscape. Plants often serve as sexual symbolic motifs for the artist. A defoliating corncob fruit hovers phallically above the kneeling woman. The approaching emperor spreads his arms longingly - in the form of white wings. Is it the swan knight “Lohengrin”, who rescued the duke's daughter Elsa in the Wagner opera of the same name? Blankenhorn, who had lost her singing voice after a nervous crisis, would have liked to become a singer and probably identified with this operatic figure. In her pictorial world, she lives with Kaiser Wilhelm II who is a swan knight. However, a sexual rapprochement is not depicted - the figures remain pure and white and are embedded in the landscape green. Only the spherical motif, which swells diagonally from the lower left to the upper right, suggests a sexual dynamic growing from the female to the male figure. At the upper right edge of the picture the emperor is enveloped by a red aureole. Is it a symbol of ripening grapes? Or the still unplucked apple of sin?

Blankenhorn distinguished the actual reality from a “spiritual reality”. She asked her psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger: “Do you consider thoughts to be the foundation or life? For me it is the thoughts, because I have no other life than getting up and going to bed. Thought life is real, after all.”

The Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg showed a retrospective of this artist from Sept. 15, 2022 to Jan. 22, 2023.

Text by Ingrid von Begue, Curator of the Prinzhorn Collection.

We are always looking for interesting and visually appealing images for the cover of the Journal andwould welcome suggestions or pictures,which should be sent to Dr Allan Beveridge, British Journal of Psychiatry, 21 Prescot Street, London, E1 8BB, UK or bjp@rcpsych.ac.uk.

Highlights of this issue

Highlights of this issue

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. A15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Editorial

Losing the thread: experiences of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 December 2022, pp. 151-152

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Analysis

Validity of root cause analysis in investigating adverse events in psychiatry

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 February 2023, pp. 153-156

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Invited commentary

A response to the terms in Shah et al's ‘Neurodevelopmental disorders and neurodiversity: definition of terms from Scotland's National Autism Implementation Team’

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 157-159

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Paper

Health-risk behaviours among people with severe mental ill health: understanding modifiable risk in the Closing the Gap Health Study

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 January 2023, pp. 160-166

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and self-harm: Danish nationwide register-based cohort study

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 January 2023, pp. 167-174

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Correspondence

RE: Proposed Assisted Dying Bill: implications for mental healthcare and psychiatrists

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 175

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Authors’ reply. RE: Proposed Assisted Dying Bill: implications for mental healthcare and psychiatrists

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 175-176

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

RE: Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychiatric mother and baby units: quasi-experimental study

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 176-177

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

RE: Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychiatric mother and baby units: quasi-experimental study

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 177

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Author's reply. RE: Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychiatric mother and baby units: quasi-experimental study

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 178

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Book Review

A Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking and Radical Enlightenment By Bruce E. Levine. AK Press. 2022. £17.00 (pb). 270 pp. ISBN 9781849354608

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 179

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Antisocial Personality: Theory, Research, Treatment By Richard Howard and Conor Duggan Cambridge University Press. 2022. £29.99 (pb). 220 pp. ISBN 9781911623984

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 179-180

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Kaleidoscope

Kaleidoscope

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 182-183

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Extra

Reflections on Franz Gall and phrenology – Psychiatry in history

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 174

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

BAD – Poem

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. 184

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Front Cover (OFC, IFC) and matter

BJP volume 222 issue 4 Cover and Front matter

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. f1-f3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Back Cover (IBC, OBC) and matter

BJP volume 222 issue 4 Cover and Back matter

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, p. b1

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation