Psychomotor agitation, defined as excessive motor and verbal activity associated with a feeling of inner tension, according to the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5, 1 is commonly associated with a number of different psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Reference Alderfer and Allen2,Reference Hankin, Bronstone and Koran3 Agitation may escalate at times, even to the point of necessitating physical restraint or seclusion. Reference Marder4 In busy emergency departments, the speed of treatment onset is generally considered the most important criterion when selecting anti-agitation medication. Reference Alderfer and Allen2

There are currently several treatments and formulations available for treating agitation in patients with psychiatric illnesses. Reference Nordstrom and Allen5 Although oral loxapine is an established treatment for schizophrenia, the intramuscular formulation has been used in some countries to treat agitation. Reference Bourdinaud and Pochard6 The intramuscular loxapine formulation was previously approved and marketed but is no longer available in the USA. However, an inhaled formulation of loxapine (Adasuve®, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Mountain View, California, USA) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration is available for the treatment of agitation in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. 7,8

The effects of the inhaled formulation of loxapine on agitation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder have been investigated in two Phase III clinical trials (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00628589, NCT00721955). Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 Notable results from the two studies include statistically significant reductions in the primary outcome measure, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component (PANSS-EC) score, v. placebo at 2 h post administration. These statistically significant reductions (P<0.0001) were observed in PANSS-EC scores 10 min post administration, the earliest assessment time point in both studies. This is substantially earlier than the observed onset of the pharmacological effects for the oral or intramuscular loxapine formulations (<30 min). Reference Citrome11 Furthermore, statistically significant changes in the Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I) score (P<0.0001) demonstrated clinically relevant improvements, with more patients in the loxapine-treated groups classified as much improved and very much improved compared with the placebo group. Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 Citrome examined the effect size in these two studies over time. Reference Citrome11

PANSS-EC (also known as PEC) represents a simple clinical scale used to assess agitation level in patients. Reference Montoya, Valladares, Lizan, San, Escobar and Paz12 PANSS-EC is part of the PANSS scale, a more comprehensive measure that includes an additional four components: negative, positive, disorganised (cognitive) and depression anxiety. Reference Emsley, Rabinowitz and Torreman13 The PANSS-EC scale is used in clinical trials and comprises five items associated with agitation: poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness and excitement. The PANSS-EC score is the sum of these five items. The PANSS-EC score has not been used regularly in clinical settings, but it has become the accepted assessment for agitation in recent pivotal clinical trials for recently approved agitation treatments. Reference Leucht, Kane, Kissling, Hamann, Etschel and Engel14 Recently, the validity and ability of the PANSS-EC scale to detect changes in agitated patients has been demonstrated, together with a strong linear correlation with scales such as CGI Severity. Reference Montoya, Valladares, Lizan, San, Escobar and Paz12

Analyses of the different assessment scales to validate their usage in assessing agitation has indicated that a 38% reduction in PANSS-EC score correlates to a CGI-I rating of much improved. Reference Montoya, Valladares, Lizan, San, Escobar and Paz12 Thus, a 40% reduction in PANSS-EC score has been considered a clinically relevant reduction in similar studies of antipsychotics. Reference Pratts, Citrome, Grant, Leso and Opler15,Reference Citrome16

Defining a responder as a patient with achievement of a specified (clinically meaningful) reduction in PANSS-EC score, and examining the percentage of patients achieving this reduction, can provide a clinical standard for PANSS-EC reduction in the treatment of agitation and facilitate the comparison of efficacy between different antipsychotics.

We performed a post hoc analysis of the results from the two Phase III clinical studies Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 to determine the percentage of patients achieving a clinical response, defined as a reduction of ≥40% in PANSS-EC score. We also examined the individual items of the PANSS-EC (poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness and excitement) to assess how each responded to treatment and contributed to the total (PANSS-EC) over time.

Method

Study design

The analyses presented here comprise data from two previously described Phase III trials of inhaled loxapine (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00628589, NCT00721955). Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 These studies demonstrated the safety, efficacy and tolerability of 5 and 10 mg doses of inhaled loxapine for the treatment of acute agitation in patients with schizophrenia Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9 or bipolar I disorder. Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 The doses used in these studies were selected based on previous clinical research showing that doses ≤10 mg were well tolerated and demonstrated superiority to placebo in reducing agitation. Reference Cassella, Fishman and Spyker17,Reference Spyker, Munzar and Cassella18

The Phase III clinical trials of inhaled loxapine were multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group and repeat-dose (up to three doses if required) trials conducted in the USA. The studies were designed and performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation E6 Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki and US Food and Drug Administration and European Union guidelines. Independent institutional review boards approved the studies, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Description of patients

Eligible patients were males and females aged 18–65 years, otherwise in generally good health, diagnosed with either schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder based on DSM-IV-TR criteria 19 by a research-trained psychiatrist. The patients were clinically agitated at baseline according to PANSS-EC score. Eligible patients had a PANSS-EC score ≥14, with at least one of the five items rated ≥4.

The PANSS-EC is scored by summing the ratings of the five items associated with agitation (poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness and excitement), rated on a scale from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). Total scores thus range from 5 to 35, Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler20,Reference Kay21 and scores ≥20 correspond to clinically severe agitation. Reference Montoya, Valladares, Lizan, San, Escobar and Paz12

Randomisation, treatment and assessments

Patients were randomised 1:1:1 to inhaled loxapine 5 mg, inhaled loxapine 10 mg or placebo. Assessments were performed at baseline and at 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min and 2, 4 and 24 h following the initial dose. If required, a second dose was allowed following completion of the 2-h assessment, and a third dose was allowed at or after 4 h following dose 2. Lorazepam rescue was permitted at any time after dose 2.

Drug administration

Inhaled loxapine was delivered via the Staccato® system (Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Mountain View, California, USA), described in detail elsewhere. Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Dinh, Myers, Noymer and Cassella22 Briefly, it is a hand-held drug device that facilitates rapid systemic delivery of loxapine via inhalation of a thermally generated aerosol with intravenous-like kinetics and a median time to maximum concentration of 2 min. Reference Dinh, Myers, Noymer and Cassella22 Oral inhalation through the device triggers the controlled rapid heating of a thin film of excipient-free loxapine to form a pure-drug vapour.

Clinical end-points

The original primary end-point of the studies included in this analysis was change from baseline in PANSS-EC score 2 h post dose (5 or 10 mg) compared with placebo. Secondary end-points were change from baseline in PANSS-EC score at each assessment time point up to 2 h, change from baseline in PANSS-EC score stratified by median baseline PANSS-EC score and increase in the CGI-I responder analysis.

The current post hoc analysis of the PANSS-EC scores evaluated the change from baseline for each individual PANSS-EC subscale item (poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness and excitement) and the percentage of PANSS-EC responders (patients achieving ≥40% improvement over baseline scores, defined as Response-40) at each assessment time point.

Statistical analysis

The efficacy population included all patients who received any study drug and had both a baseline assessment and at least one post-dose efficacy assessment. Statistical testing of the post hoc end-points used a two-way non-parametric analysis of covariance by ranks (within strata). PANSS-EC responder analysis comparisons between the treatment and placebo groups were calculated by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test (pairwise) using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Forest plots and confidence intervals were calculated using StatsDirect version 2.8.0 (StatsDirect, Cheshire, UK).

The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve a response was calculated to help place the response results into clinical context. NNT was calculated as 1/(% response rate for treated − % response rate for control).

Results

Patient disposition

In the schizophrenia study, 344 patients received at least one dose of study drug, of whom 338 completed the study. Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9 In the bipolar I disorder study, 314 patients received at least one dose of study drug and 312 patients completed the study. Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 Patient baseline characteristics for both studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Patient baseline characteristics

| Patients with schizophrenia | Patients with bipolar I disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Placebo n=115 | 5 mg n=116 | 10 mg n=113 | Placebo n=105 | 5 mg n=104 | 10 mg n=105 |

| Mean (s.d.) age, years | 48.3 (9.5) | 43.2 (10.2) | 42.1 (9.8) | 40.6 (9.8) | 41.2 (9.6) | 40.5 (9.8) |

| Mean (s.d.) time since diagnosis, years | 18.8 (10.3) | 16.5 (10.8) | 18.2 (10.0) | 12.0 (10.1) | 12.8 (8.9) | 11.7 (9.1) |

| Mean (s.d.) duration of current agitation episode, days | 6.9 (9.2) | 6.1 (7.5) | 7.6 (11.5) | 14.2 (21.5) | 16.0 (32.4) | 9.7 (10.2) |

| Mean (s.d.) number of previous hospitalisations | 9.6 (9.0) | 9.2 (12.2) | 9.7 (11.3) | 5.9 (6.6) | 5.5 (6.6) | 5.0 (6.4) |

| Male, % | 70 | 77 | 75 | 53 | 45 | 51 |

| Smokers, % | 78 | 81 | 86 | 74 | 76 | 73 |

| Mean (s.d.) baseline score on items of the PANSS-EC scale a | ||||||

| Poor impulse control | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.8) |

| Tension | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.6) |

| Hostility | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.2 (0.9) |

| Uncooperativeness | 3.0 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.7 (1.0) |

| Excitement | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) |

PANSS-EC, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component.

a Each of the five individual items is rated on a scale of 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme).

PANSS-EC responders

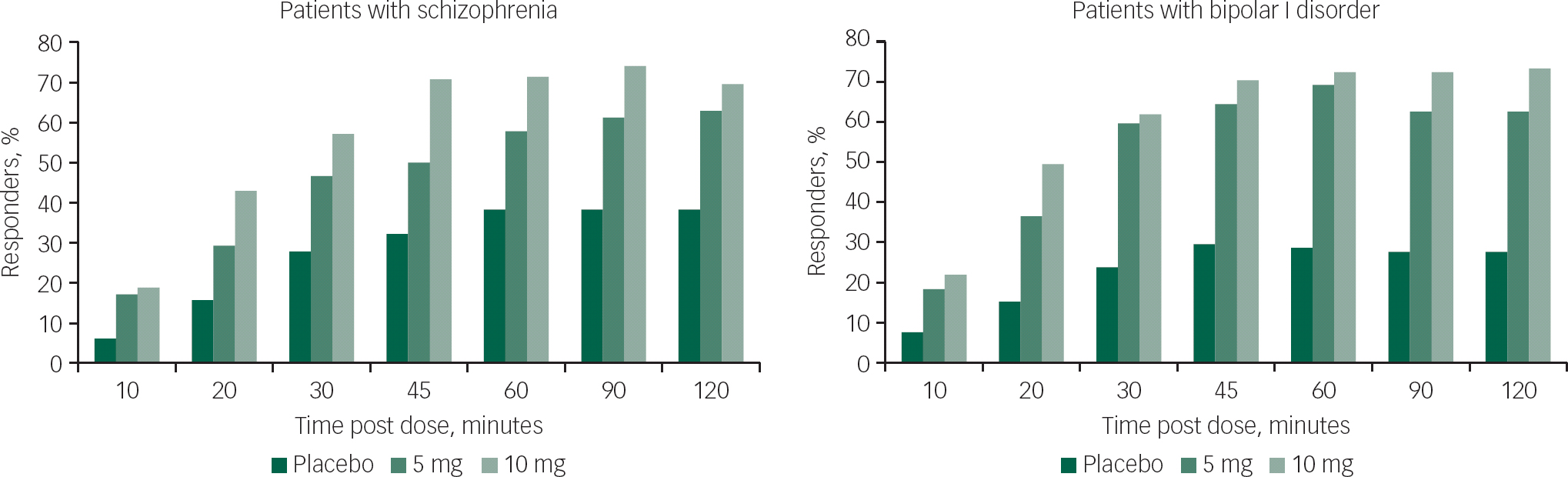

A reduction in agitation of ≥40% in PANSS-EC score (Response-40) was observed in ~20% of patients with schizophrenia and those with bipolar I disorder at 10 min post loxapine dose (Fig. 1). This reduction was observed in patients receiving both the 5 and 10 mg doses. The percentage of patients achieving Response-40 increased with time, reaching a peak of ~70% in the 10-mg dose group for both the schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder groups.

Fig. 1 PANSS-EC response over time: patients with ≥40% PANSS-EC score reduction. PANSS-EC, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component.

The percentages of PANSS-EC responders in the two loxapine dose groups (5 and 10 mg) were statistically significantly higher than placebo at the 10 min time point (P=0.0056 and P=0.0012 for the schizophrenia study; P=0.0059 and P=0.0017 for the bipolar I disorder study). Statistical significance v. placebo was maintained through all time points through 2 h for both the 5 and 10 mg doses in both studies (Fig. 1).

Figure 2 shows the odds ratio (OR) at the 2 h time point for 5 and 10 mg to placebo for each study for the CGI, PANSS-EC and each subscale. PANSS-EC OR shows a similar and slighter stronger response compared with CGI OR. The three individual items’ (impulse control, tension and excitement) ORs show a similar response pattern, and all five items are statistically significant (P<0.05) as indicated by the OR confidence interval (CI) exclusion of 1.0.

Fig. 2 Odds ratio (OR) forest plot for responders at 2 h: CGI responders, total PANSS-EC scores and individual PANSS-EC subscale scores. BD, bipolar I disorder; CI, confidence interval; CGI, Clinical Global Impression scale; OR, odds ratio; SC, schizophrenia; PANSS-EC, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component. All ORs are statistically significant (95% CI excludes 1.0).

The NNT for the PANSS-EC at the 2 h time point for the 5 and 10 mg treatment v. placebo was 4.05 and 3.16 for the schizophrenia study and 2.87 and 2.19 for the bipolar I disorder study.

PANSS-EC items

In both studies, there were statistically significant reductions in all five PANSS-EC items for the 5 and 10 mg doses v. placebo at 2 h post dose (Fig. 3). Overall, score reductions in all PANSS-EC items across the two studies were between 1 and 2 units from baseline for both doses over the first 2 h post dose. Both the 5 and 10 mg dose groups reduced statistically significantly (P<0.05) for all PANSS-EC item scores v. placebo at each time point through 2 h (Fig. 3), with the exception of the uncooperativeness subscale, where P=0.0853 for the 5 mg dose at 10 min in the schizophrenia study.

Fig. 3 Changes from baseline in individual PANSS-EC item scores at 2 h post dose (bar graph) and changes in individual PANSS-EC item scores over time (line graphs). PANSS-EC, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component. In the individual PANSS-EC item analyses, all time points from 10 min to 2 h for both doses were statistically significant (P<0.05), except for the uncooperative item (P=0.0853 for the 5 mg dose at 10 min in the schizophrenia study).

Discussion

The present post hoc analysis demonstrates that a statistically significantly greater percentage of patients achieved ≥40% reduction in agitation assessed by PANSS-EC score at 2 h following administration of inhaled loxapine at both the 5 and 10 mg doses, compared with those who received placebo. This result was observed in both the schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder populations studied.

The percentage of patients who achieved ≥40% reduction in PANSS-EC score in the loxapine-treated groups was statistically significantly greater v. placebo as early as the 10-minute post-dose assessment, confirming the rapid onset of effect seen in the original clinical trials. Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10

Analysis of the individual items of the PANSS-EC scale show statistically significant reductions in scores for each of the five items v. placebo as early as 10 min post dose and at the 2 h time point for both the 5 and 10 mg doses of loxapine and in both studies. Thus, it can be concluded that each of the five PANSS-EC items contributed to the reduction in the PANSS-EC score observed with inhaled loxapine treatment. The total PANSS-EC score may represent a larger effect size than any individual subscale.

Comparison with similar studies on agitation management where 40% reduction in PANSS-EC score was used as an outcome Reference Pratts, Citrome, Grant, Leso and Opler15,Reference Citrome16 revealed that although the inclusion criteria varied among the studies, patients’ baseline and demographic characteristics were similar: mean PANSS-EC scores ranged from 17.3 to 19.0 and the average score range per item was 3.5–3.8 for aripiprazole, olanzapine and inhaled loxapine. Reference Citrome16 In a similar study of quetiapine, Reference Pratts, Citrome, Grant, Leso and Opler15 50% of patients achieved ≥40% reduction in PANSS-EC score at 2 h post dose. Although a direct comparison cannot be made with the results of this analysis due to the differences in inclusion criteria and the number of patients analysed, a greater proportion of patients (70%) achieved ≥40% reduction in PANSS-EC score at 2 h post dose with inhaled loxapine, confirming treatment efficacy.

Limitations

The post hoc analysis of the PANSS-EC results described here has several limitations. One limitation is that the treatment was performed in a controlled healthcare setting, which may not necessarily be representative of the clinical setting where this treatment will be used. Another limitation is that patient groups provided informed consent and were screened to meet eligibility criteria; hence, patients who were too agitated to give consent were excluded. This would not be the case for the patient population who would receive treatment for agitation in a clinical setting. In addition, the application of a 40% reduction in PANSS-EC score was performed post hoc, and the clinical relevance of the 40% reduction is unclear. Nonetheless, the ≥40% reduction in PANSS-EC score at 2 h post dose was chosen to be consistent with other antipsychotic studies for similar patient groups and was based on its correlation observed with other measuring scales. 7,8,Reference Montoya, Valladares, Lizan, San, Escobar and Paz12

The analysis of the Phase III clinical trials of inhaled loxapine demonstrates a rapid onset of action (within 10 min of administration) across all items of the PANSS-EC, confirming the results in the original Phase III studies, Reference Lesem, Tran-Johnson, Riesenberg, Feifel, Allen and Fishman9,Reference Kwentus, Riesenberg, Marandi, Manning, Allen and Fishman10 and highlights the effectiveness of inhaled loxapine on all components of agitation included in the PANSS-EC scale.

Funding

This study was funded by Alexza Pharmaceuticals. Medical writing support was funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Paul Littlebury, PhD, of Excel Scientific Solutions, Horsham, UK.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.