Pregnancy is a time of dynamic physical, emotional and social change. Mental health difficulties are prevalent in pregnancy, with anxiety-related problems being particularly common, affecting approximately 15% of women.Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1 Anxiety-related difficulties include a range of presentations, encompassing obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social anxiety and panic disorder. These problems are often accompanied by pregnancy-related anxiety.Reference Nath, Lewis, Bick, Demilew and Howard2 The disorders may exist prior to conception, but for many women the experience of clinical anxiety is new in pregnancy.Reference Fairbrother, Janssen, Antony, Tucker and Young3 Women with prior mental health difficulties, additional social stressors and a history of loss may be more likely to experience poor mental health in pregnancy, and this can be compounded by stressful events that occur within the pregnancy, including pregnancy complications.Reference Charrois, Mughal, Arshad, Wajid, Bright and Giallo4,Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante5 Persistent anxiety is not only distressing and disabling for women, but can potentially affect the pregnancy, birth and developing child.Reference Ding, Wu, Xu, Zhu, Jia and Zhang6 Large cohort studies have highlighted subsequent effects of antenatal anxiety on offspring during childhoodReference O'Donnell, Glover, Barker and O'Connor7 which may be related to both genetic and environmental factors, including the intrauterine environment.Reference Ahmadzadeh, Schoeler, Han, Pingault, Creswell and McAdams8 A number of studies have also found antenatal anxiety to be associated with more challenging experiences of postnatal parenting and parental stress.Reference Thiel, Iffland, Drozd, Haga, Martini and Weidner9,Reference Huizink, Menting, Moor, Verhage, Kunseler and Schuengel10 Therefore, the need to treat anxiety effectively in pregnancy to alleviate the impact on women and offspring is of clear importance.

Women have a strong preference for psychological therapies in pregnancy, possibly owing to concerns about teratogenic effects of medications.Reference Arch11 Cognitive–behavioural approaches for anxiety-related problems have a substantial evidence base,Reference Norton and Price12 but their use in pregnancy is much less researched. Studies have emphasised the need to adapt treatments to the perinatal context, with women valuing therapist knowledge and flexibility in delivery of sessions.Reference O'Mahen, Fedock, Henshaw, Himle, Forman and Flynn13 However, high drop-out rates are often observed in perinatal treatment studies,Reference Orhon, Soykan and Ulukol14 which may be due to a range of factors, including financial and logistical barriers, the increasing physical impacts of pregnancy, non-tailored care, stigma and lack of trust in professionals. Pregnant women often have many other competing demands to manage, such as medical appointments, other caregiving responsibilities and paid employment.Reference Smith, Lawrence, Sadler and Easter15

Time-intensive treatments deliver the treatment protocol over a shorter period (typically 1–2 weeks) in longer and more frequent sessions, and have been found to be effective in the treatment of OCD, PTSD, social anxiety and panic disorder.Reference Remmerswaal, Lans, Seldenrijk, Hoogendoorn, van Balkom and Batelaan16 This form of delivery has been found to be effective and acceptable for women with postpartum OCDReference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson17 and may be a good fit given the time frame of pregnancy. An effective treatment dose earlier on could alleviate distress in the remainder of the pregnancy and thereby potentially improve a range of outcomes. Therapy delivered in fewer, longer sessions may be easier to manage around other demands and so lead to better adherence and engagement. One key component of therapy for anxiety problems is in vivo exposure to feared stimuli (for example to traumatic memories, unwanted sensations, feared situations) to facilitate new learning, which is an important element of treatment efficacy.Reference Maguire, Clark and Wootton18 However, therapist reluctance to conduct exposure has been documented in non-perinatal studies,Reference Meyer, Kelly and Deacon19 and in surveys pregnancy is cited as a common reason for withholding or delaying treatment.Reference Meyer, Farrell, Kemp, Blakey and Deacon20,Reference Hendrix, Sier, Baas and van Pampus21 In one study, almost half of surveyed therapists reported having heard that treatment of PTSD in pregnancy was harmful and over 30% reported reluctance to treat pregnant women.Reference Hendrix, Sier, Baas and van Pampus21 Therapist beliefs about upsetting or unbalancing the patient or harming the fetus can be activated, leading to therapist avoidance of this exposure. Concern is founded on the notion that exposure treatments may elevate anxiety and this may confer a risk to the developing fetus, given the known burden of chronic prenatal stress and anxiety.Reference O'Donnell, Glover, Barker and O'Connor7 However, this approach disregards the fact that women are already experiencing high levels of anxiety at the start of therapy and the evidence that anxiety reduces with exposure interventions.Reference Arch, Dimidjian and Chessick22 The common exclusion of pregnant women from cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) trials has compounded this issue. Given the high prevalence of anxiety-related problems in pregnancy and the existence of effective treatments, it is important to explore the perspectives of women and therapists. This study aimed to understand the views of women and treating therapists on the experiences of providing and receiving cognitive–behavioural treatment including exposure in pregnancy. It also aimed to understand whether time-intensive treatment was a helpful and acceptable adaptation.

Method

Study design

Participants were women and therapists who had been part of a feasibility randomised controlled trial testing two forms of delivery of CBT for anxiety problems in pregnancy, delivered in a primary care setting.Reference Challacombe, Potts, Carter, Lawrence, Husbands and Howard23 Women with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (OCD, PTSD, social anxiety or panic disorder) received predominantly online time-intensive or standard weekly CBT. The majority of treatment took place in pregnancy, with a follow-up at 1 month postpartum. Time-intensive CBT involved undertaking an initial 8–10 h of therapy in the first 2 weeks of treatment, with subsequent antenatal sessions at monthly intervals, whereas weekly CBT comprised 1 h per week throughout pregnancy. Thus, 8–11 h of antenatal contact time was planned in both arms, with an additional 1 h postpartum follow-up. A limited number of additional CBT sessions were allowed if women required further contact postpartum. All women who had taken part were invited to complete a final research assessment at approximately 3 months postpartum and invited to participate in a semi-structured interview as part of this.

Women gave written informed consent to take part in the research and interview at the outset of the trial. Recruitment took place between 1 September 2019 and 24 September 2021 (Fig. 1). Six out of eight possible therapists were approached to take part – one of the eight had left the service and one was conducting this qualitative analysis (F.L.C.). All therapists were experienced in working with perinatal women prior to the trial, with between 3 and 25 years of post-qualification clinical experience of CBT and all were female.

Fig. 1 Flow of participants through the study. IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; exc, excluding; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; ITT, intention to treat.

Our qualitative approach was underpinned by an interpretivist ideology that aimed to understand experiences of therapy from the perspectives of those who will provide and receive it. Participant interviews were conducted by two female Masters level graduate students not otherwise involved in the trial (K.S. and S.J.) who had undertaken qualitative methods training as part of their Masters degrees. At the outset of participant interviews, the interviewer was masked to group participation (but was unmasked as the participants discussed their experiences, including the intensive or weekly format). Interviews took place online over Microsoft Teams and were recorded for transcription. Interviews were not returned to participants. Interviewees were aware that the interviewers were undertaking the project as part of the process evaluation of the ADEPT trialReference Challacombe, Tinch-Taylor, Sabin, Potts, Lawrence and Howard24 and were aware of the background of the researchers. Data were analysed by K.S. and F.L.C., who is an active clinician and researcher in the field of perinatal anxiety and chief investigator of the trial. Regular discussion on data collection and analysis took place with V.L., who is an expert in qualitative methods and member of the research team. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guideline was used to support the transparent reporting of the research.Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig25

Ethical considerations

A multicentre, parallel-group feasibility randomised controlled trial of standard (weekly) versus intensive exposure-based CBT (1:1) was conducted. A full protocol was published consistent with the SPIRIT guidance.Reference Challacombe, Potts, Carter, Lawrence, Husbands and Howard23 The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by London-Surrey Borders research Ethics Committee (19/LO/0622).

Interviews

The topic guides for the mother interviews were developed from the literature, discussions with experts by experience and clinicians working in this field. Possible additional prompts and observations were noted by F.L.C. and K.S. as the trial continued. Owing to the timing of the trial, questions were added about online therapy and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of the mother interviews was to explore the experiences of women and to identify any benefits and/or harms from the intervention or participation in the study (see the Supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.585 for topic guides). The topic guide for the therapist interviews was developed with the research team. Data collection and analysis overlapped, allowing us to review when we had achieved information powerReference Malterud, Siersma and Guassora26 and collected sufficiently rich and diverse data to answer our research question.

Data analysis

We conducted reflexive thematic analysis using inductive codes to develop conceptual themes, using NVivo version 12 for Windows qualitative analysis software (QSR International) to help organise the data. The six phases outlined by Braun & Clarke were followed.Reference Braun and Clarke27 Transcripts were first checked against interview recordings for accuracy. Analysis began with re-reading of transcripts and listening to audio files for immersion. Two of the researchers (K.S. and F.L.C.) read the first three participant transcripts repeatedly to immerse themselves in the data; they then independently developed initial codes and provisional themes and discussed with a third researcher (V.L.) to examine different interpretations of the data and enhance reflexivity. Reflexive thematic analysis values researcher subjectivity while recognising the importance of critically reflecting on the knowledge that is produced. Involving others in the analysis helped the lead author to understand how her personal experiences of pregnancy, motherhood, therapy and perinatal mental health research, and role as principal investigator of the study, might have influenced expectations, assumptions and interpretations. This process was repeated after 10 interviews had been coded. Therapist data were coded by F.L.C. and discussed with V.L., informing provisional themes that overlapped with the patient data. The provisional themes were discussed in the research team and the perspectives of both groups of participants were amalgamated to develop rich and nuanced overarching themes. Remaining data were coded into themes and subthemes relating to participant and therapist experiences and attitudes towards treatment.

Patient and public involvement

Women who had experienced perinatal mood and anxiety disorders were involved in the design of the study, and a lived experience group was established to advise on the progress and results of the study, including feedback on qualitative results. This group advised that the mother interview topic guide was suitable and at the results stage advised that that it was particularly important to take the practicalities of intensive therapy into account for women. A person with lived experience was also part of the data monitoring committee.

Results

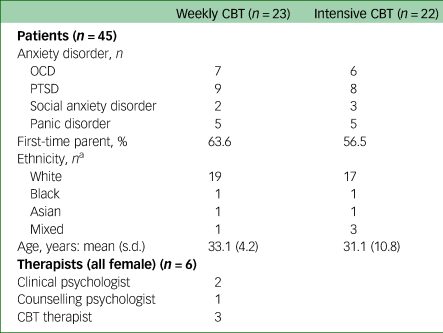

In total, 45 women who had participated in the ADEPT trial (of a total possible 59 randomised) were interviewed, including one woman who had dropped out of treatment. Two women did not have time for the interview but provided quantitative data for the research assessment; the remaining women were not available for follow-up. Six (of a possible eight) therapists who had conducted the vast majority of intervention in the trial were interviewed about their experiences. All therapists had delivered both weekly and time-intensive treatments (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of participants

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

a. One person declined to give their ethnicity.

Qualitative themes and subthemes

Themes were generated using data from both women and therapists. Themes and subthemes are summarised in Table 2 and discussed in detail below. Participants’ names are replaced with pseudonyms, and disorder and mode of therapy (WCBT, weekly CBT; INT, intensive CBT) are shown.

Table 2 Themes and subthemes of the qualitative analysis

Theme 1: Acquiring tools to navigate the perinatal period

An overarching theme of using therapy as a means to navigate the perinatal period was described. Women spoke of the use of tools and techniques to help with their anxiety, with some mentioning specific examples such as reducing excessive internet-based reassurance-seeking or using stimulus discrimination in PTSD. The normalising of anxiety or intrusive thoughts, allowing women to understand their experiences, was mentioned by several as helpful. For those with panic disorder, understanding that sensations were not dangerous was important. Women across disorder groupings mentioned mapping out the problem (formulation) as helpful to understanding and changing their thoughts and behaviours. Women liked the individual and flexible approach to their difficulties:

‘I definitely did think it was a positive experience for me in terms of addressing my anxiety and she gave me some techniques when I'm experiencing particularly, like, physical symptoms to bring myself back into the moment. And that was really helpful. And she taught me some really good techniques to help me deal with my anxiety.’ (Mary: PTSD-WCBT)

Some women described limitations in terms of improvements in some aspects of mental health, highlighting that not all aspects were addressed by the therapy. Many also recognised that therapy was the beginning of an ongoing process and the need to keep actively applying the tools to continue to make progress. Therapists also reflected on the improvements seen in many of their patients.

Better equipped for birth and parenthood

Several women reported feeling more confident with the birth process and in asking for assistance if they needed, as well as feeling calmer in general. Women had spoken about reducing the impact of their anxiety on parenting as a motivation for seeking treatment and several mentioned benefits overall to their sense of anxiety and confidence as a parent, and that they had become more relaxed. Some described specific strategies learned in therapy that they were applying to parenting:

‘I do tend to worry about how good a mother I am. But it has helped me to have strategies, and, instead of worrying about it, to spend more time engaging with her.’ (Rona: Panic-INT)

Therapy as a means to improve relationships

Many women mentioned a positive effect of therapy on relationships with partners, either by being involved in the sessions and gaining more understanding of the problem themselves or when women started to apply what they had learned in treatment, for example by partners being less involved in reassurance-seeking or, indirectly, by the mother being calmer in general:

‘I think it had a positive effect on my closest relationships, because in pregnancy, especially with lockdown as well, they were the people that had to deal with my intrusive thoughts when I shared them, and my worries every day.’ (Ruby: OCD-INT)

Therapists reflected on the importance of considering partner involvement as the women progressed through therapy.

Theme 2: Motivated yet constrained by pregnancy

Pregnancy context as integral to therapy

Therapists and women reflected on ways that the time frame and context of pregnancy were interwoven with the therapy. Women felt pregnancy was a good time for them to have had the therapy to help them prepare for birth and parenthood:

‘to have someone with you as it happens and to say “I've got a scan next week. How do I prepare for this?”, you know, and to have someone giving you those kind of real-life live tools and tricks made all the difference, like, rather than having it before you get pregnant or whatever and then trying to apply it in a time where, you know, a lot's going on. So, for me it was really, really helpful having it at that point.’ (Jemima: PTSD-WCBT)

Some women who had had intensive CBT, particularly those with PTSD, commented that this was a particularly good time to work on things and make rapid progress, in order to enjoy the pregnancy more.

Women spoke about the importance of committing to the therapy, making the most of it and trying to prioritise it at this time. For some, this was recognised more retrospectively. Therapists noted the importance of starting therapeutic work as early as possible in the pregnancy, particularly in the case of trauma work. If additional physical problems arose as pregnancy progressed then this made delivery of treatment more difficult as women were potentially increasingly anxious and preoccupied with those, with less capacity to challenge their anxiety, and some had additional maternity appointments to negotiate. Normalisation of experiences was a very helpful tool for therapists and they recognised a need for ongoing reflection on what was normal or excessive in the context of pregnancy:

‘It's really important to understand how their pregnancy's affecting their anxiety and to really think about how their anxiety is affecting their pregnancy as well because, you know, in my experience to date and through the trial people's anxiety was much higher than it was outside of their pregnancy.’ (Therapist 2)

Overcoming physical and social barriers

Many women mentioned tiredness during pregnancy as affecting the sessions or homework to some extent, particularly as the pregnancy progressed. Having intensive sessions was particularly tiring for some, but others felt that these came at the right time before they became tired later in pregnancy. Some, but not all, of the women felt that being pregnant may have made them more emotionally labile, affecting both their anxiety and the therapy. Therapists frequently noted that their patients were very busy, and fitting therapy and homework around paid employment was difficult. This was mirrored by comments from women in both intensive and weekly therapy, with intensive therapy placing more demands on women regarding homework tasks. Some thought the intensive therapy was easier to fit in because it was short term, but some from this group and many in the weekly group felt that weekly sessions were more practical to fit around work demands:

‘I did struggle with the amount of homework I had to do. I think because I was working full-time as well, yeah, I struggled a little bit with that, so I'd say that was probably the one thing that I would like to have done differently.’ (Amal: PTSD-WCBT)

Furthermore, therapists noted that women experiencing additional issues may have found it harder to engage with the treatment:

‘You know people are struggling with symptoms and stuff like physical symptoms. I think that you need to be a bit more flexible and unfortunately services aren't always very flexible.’ (Therapist 2)

Therapists pointed out that stability of circumstances is a necessary condition to use therapy and noted their impression that those mothers who were also dealing with social problems such as insecure housing did less well. Therapists commented that this was often intersectional, with more women from minority ethnic backgrounds experiencing these problems. They emphasised the importance of flexibility in service provision and cancellation policies to allow women time to trust and engage, of particular importance for groups experiencing marginalisation.

Theme 3: Having the confidence to face fears and tolerate uncertainty

Therapeutic relationship as the foundation for exposure

Therapists endorsed the use of exposure techniques with pregnant patients and noted the importance of explaining the rationale clearly and being confident with patients in this part of the therapy. Pregnant women were described as being both more motivated and more cautious than non-perinatal patients, and they were mindful of any theoretical impact on the baby, which was sometimes discussed in treatment:

‘being really clear on what the work involves and being really confident in how some of the work involves exposure and increasing your anxiety and how that's safe is really important in this population…’ (Therapist 2)

Women themselves repeatedly emphasised the importance of the therapeutic relationship in helping them approach their fears during exposure exercises, and the subsequent value of having done this:

‘I feel braver and I feel like I can tolerate the discomfort of “Oh God, is this going to be okay?” more because of having done it with support…’ (Tania: Panic-WCBT)

‘I really hated that [exposure] with a fiery passion, but I did it and I think it was really useful…’ (Sarah: PTSD-WCBT)

Therapists modified exposure according to what the patients could physically and emotionally manage and noted a view that conducting exposure exercises very late in pregnancy (i.e. after 35 weeks) was not advisable, owing to the uncertainty surrounding how many sessions remained before birth and the need to focus and prepare for this event.

Sitting with uncertainty

All therapists noted that the work of supporting exposure sometimes brought up internal therapist beliefs and doubts about harm to the baby. They did not feel that this changed what they did in treatment but it was something they had to tolerate in the work and this was important given that is also what is being asked of the patients. Sometimes the fears were ‘contagious’ to therapists, who then questioned their judgements, particularly where pregnancy complications arose such as gestational diabetes:

‘Sometimes, you know, we can never guarantee you a pregnancy goes to full term, we can never guarantee there won't be complications and I think sitting with that can be really unhelpful, hard, sorry, can be really, yeah, difficult, I think, for us…’ (Therapist 4)

Theme 4: Momentum with the need for flexibility

Momentum of intensive CBT

There was clear feedback from the perspectives of both women and therapists that intensive CBT engendered a fast pace of change and high momentum. Several women spoke of the benefits of intensive sessions, with things moving quickly and efficiently forward without the need for long recaps. Longer sessions allowed for coverage of a lot of material that was picked up quickly in the following session. They spoke of making quick progress owing to the amount of therapist contact. Some noted that their motivation and commitment were higher as a result of having frequent sessions. Feeling better in a shorter amount of time was also very reinforcing, and some women felt that this had allowed them to enjoy their pregnancy more by having completed the treatment earlier. By contrast some women in the weekly arm took longer to get going and notice improvements, for example noting that one missed session meant a long time before seeing the therapist again:

‘it's definitely at the forefront of your mind and to make the most of the time that you've got with the therapist. I think the intensity lends itself to really committing to using the strategies, I would say.’ (Ruby: OCD-INT)

Therapists noted a quicker response in intensive CBT and several reported a strong therapeutic alliance due to the large amount of time spent together in the first weeks. Treatment was particularly effective if women had been able to prioritise the therapy and had blocked time out for it. But women and therapists also noted that for some, more time was needed for homework tasks such as reading, carrying out experiments and emotional processing of the material between sessions. In addition to noting the challenges for patients, therapists noted the challenges of fitting sessions in their diaries and that services would need to have flexibility to offer this as a standard treatment option:

‘I think challenges logistically fitting it in, like, that was the – you know, both from my diary and their diary trying to just actually fit in sessions [was] quite tricky.’ (Therapist 3)

Therapists reflected that for women who were more difficult to engage or were dealing with other issues, having a burst of sessions and an initial ‘therapeutic dose’ may have been very useful:

‘She was able to enjoy the rest of her pregnancy a lot more, so in that way it was really beneficial. Whereas if we hadn't done that, it would have taken, yeah, 10 weeks. And that, yeah, that would have meant more time feeling distressed.’ (Therapist 1)

Being responsive to the individual situation

Therapists noted that in the intensive arm they had to be focused and were less able to respond to concerns as they arose, whereas women who received weekly treatment often reported this as a benefit of this approach:

‘It was actually helpful, so it's like obviously I was, I had a bit of a difficult pregnancy, so I was like worrying, every week there were obstacles coming up, so I knew I could talk about it in my session, that I had my session coming up.’ (Claire: PTSD-W)

Although most patients maintained the gains made during pregnancy in both treatment arms and did not need further postnatal sessions, some did require them, either because of further incidents that occurred, such as a traumatic birth, or if the original problem was related to perinatal loss or bereavement. Therapists highlighted the need for clinical flexibility in these circumstances, which are not uncommon in the perinatal period.

Theme 5: Being removed from the face-to-face world

Flexibility and barriers of online working

Women had mixed feedback regarding online therapy – many felt that it was more practical around work and the physical demands of attending (any sort of) therapy. However, for trust and engagement it was helpful to meet the therapist at least once in the treatment where that had been possible. Some but not all felt that the therapeutic alliance was stronger having met face to face:

‘we got on well together and things, but I do think it's probably just one step harder doing it through a screen. Having said that, I think any negatives are outweighed by the benefit of not having to go anywhere, like just being able to do a two-hour session rather than adding in travel time.’ (Fionn: PTSD-INT)

This was directly mirrored by the experience of therapists, who felt that the online sessions allowed some to access the service who would not otherwise have engaged:

‘And I think if I'd been seeing some of those women in person, they just wouldn't have come, like they would have cancelled, they just wouldn't have come to the session. But actually seeing them remotely meant that they could come even if it was really difficult to get out that day.’ (Therapist 2)

Similarly, online exposure exercises worked well for some women, but others felt that this aspect was more compromised and that more active work had or would have taken place in face-to-face meetings. This may have been mediated by the impact on the therapeutic alliance, or that more spontaneity occurred in face-to-face sessions.

Limitations to social connection

The online delivery of the therapy was driven by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Women spoke of missing out on social connection and family support during the pandemic, which made their anxiety and their pregnancies more difficult. Therapists and women noted that being unable to connect directly with others meant that normalising information was not available and that loneliness and isolation in the postnatal period was an additional problem they had to face.

Several therapists noted that for some women, particularly those with OCD, the pandemic made the problem more difficult to treat as it reinforced avoidance and made conducting exposure exercises very difficult:

‘With OCD, it was a bit tougher to get them to maybe do exposure and because they felt validated with the with the COVID concerns…’ (Therapist 1)

Discussion

This study is the first to explore in detail the parallel experiences of women and therapists of undertaking exposure-based CBT for anxiety problems during pregnancy. We found that women were positive about undertaking CBT during pregnancy and were motivated, often wanting to improve their anxiety and develop tools to reduce any potential impact on their baby. Generally, women reported benefits from having treatment on their mental health and on their functioning more broadly, as well as on relationships.

Previous research has identified the importance of tailored treatments in the perinatal period and of the treating therapists having specialist knowledge.Reference Lever Taylor, Kandiah, Johnson, Howard and Morant28 Our findings support this and demonstrate the particular importance of perinatal expertise in delivering exposure-based treatments confidently with pregnant women. Knowledge and understanding of what is normal in the perinatal period is crucial for therapists to be able to contextualise their patients’ experience, as well as knowledge of the impact of pregnancy complications and the pregnancy history on patients’ needs. Expertise and skills in anxiety treatments is also of obvious importance, with the ability to model a tolerance of uncertainty being key for therapists to deliver effective treatment.Reference Meyer, Kelly and Deacon19

Our findings indicate that the context of pregnancy was of also of importance to how treatments were conducted. Cognitive–behavioural approaches are very active and the logistical challenges of finding time and emotional capacity to undertake treatment is an important consideration. Good attendance and completion of homework are related to better outcomes in CBT for anxiety problems.Reference Glenn, Golinelli, Rose, Roy-Byrne, Stein and Sullivan29 The frequent sessions of intensive CBT can put pressure on time and energy for homework, and additional social stressors are likely to have a further impact on resources to complete between-session tasks:Reference Smith, Lawrence, Sadler and Easter15 both of these factors were highlighted by therapists in this study. Therapist expectations of homework for perinatal women may therefore need to be modified, given the large demands on women's time and capacity.Reference Millett, Taylor, Howard, Bick, Stanley and Johnson30 Pregnancy can be eventful and ideally the therapeutic context will be responsive to this.Reference Millett, Taylor, Howard, Bick, Stanley and Johnson30 The need for flexibility in service provision and cancellation policies was an important finding from our results.

This analysis indicated that intensively delivered therapy can be demanding for women and therapists, but our study also highlighted that for most women the momentum of this approach meant that they experienced a quick benefit, which was important in the limited time frame of pregnancy. Therefore, this seemed to be an acceptable approach to treatment delivery. It is possible that having a briefer treatment that is effective early in pregnancy could be particularly useful for those who are managing significant external pressures or subsequent pregnancy complications that may make adherence to a longer programme more difficult.

Although online treatments for mental health problems can be effective, there may be unique considerations for perinatal women.Reference Komariah, Amirah, Faisal, Prayogo, Maulana and Platini31 Our findings indicated clear pros and cons to online delivery of therapy, with women and therapists offsetting accessibility against engagement. Women highlighted the benefit of having at least some face-to-face contact, perhaps suggesting an ‘ideal’ model of hybrid work. This seems important given the key role of loneliness in maintaining perinatal mental health difficulties.Reference Adlington, Vasquez, Pearce, Wilson, Nowland and Taylor32

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was that we were able to include the perspectives of a relatively large number of women and their therapists. However, not all women who participated in the trial gave feedback on their experiences, which may have led to less representation of more negative experiences. Other limitations were that themes were not checked with participants and the sample overall lacked ethnic diversity. The therapy took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected women's mental health and necessitated online or hybrid therapy and is important context for this particular study. However, similar indications of acceptability and efficacy were found in a pre-pandemic face-to-face trial of intensive therapy for postpartum women with OCD.Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson17 Furthermore, many talking therapies services are continuing to provide online and hybrid delivery, which may be particularly popular with perinatal women, and so results may align well with current (post-pandemic) clinical practice.

Further research and service implications

Given that the exposure-based treatments were generally considered acceptable and useful by the pregnant women in our study, the effectiveness of these therapies should continue to be rigorously tested in definitive trials across a number of settings. Therapist perinatal expertise and service flexibility must be ensured to enable the successful delivery of CBT in pregnancy.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.585.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available on request from the corresponding author (F.L.C.). The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the families and therapists who participated in this research and Professor Louise Howard for her support.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: F.L.C., V.L., B.C.; data curation: K.S., S.J., F.L.C., L.P., R.T.-T.; formal analysis: F.L.C., K.S., V.L.; funding acquisition: F.L.C.; investigation: F.L.C., K.S., S.J.; methodology: V.L.; project administration: F.L.C., K.S.; writing – original draft: F.L.C.; and writing – review & editing: all authors. F.L.C. is the guarantor for the study. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (HEE/NIHR ICA Programme Clinical Lectureship to F.L.C.: ICA-CL-2017-03-013). This study is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The NIHR were not involved in the design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the study, or the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.