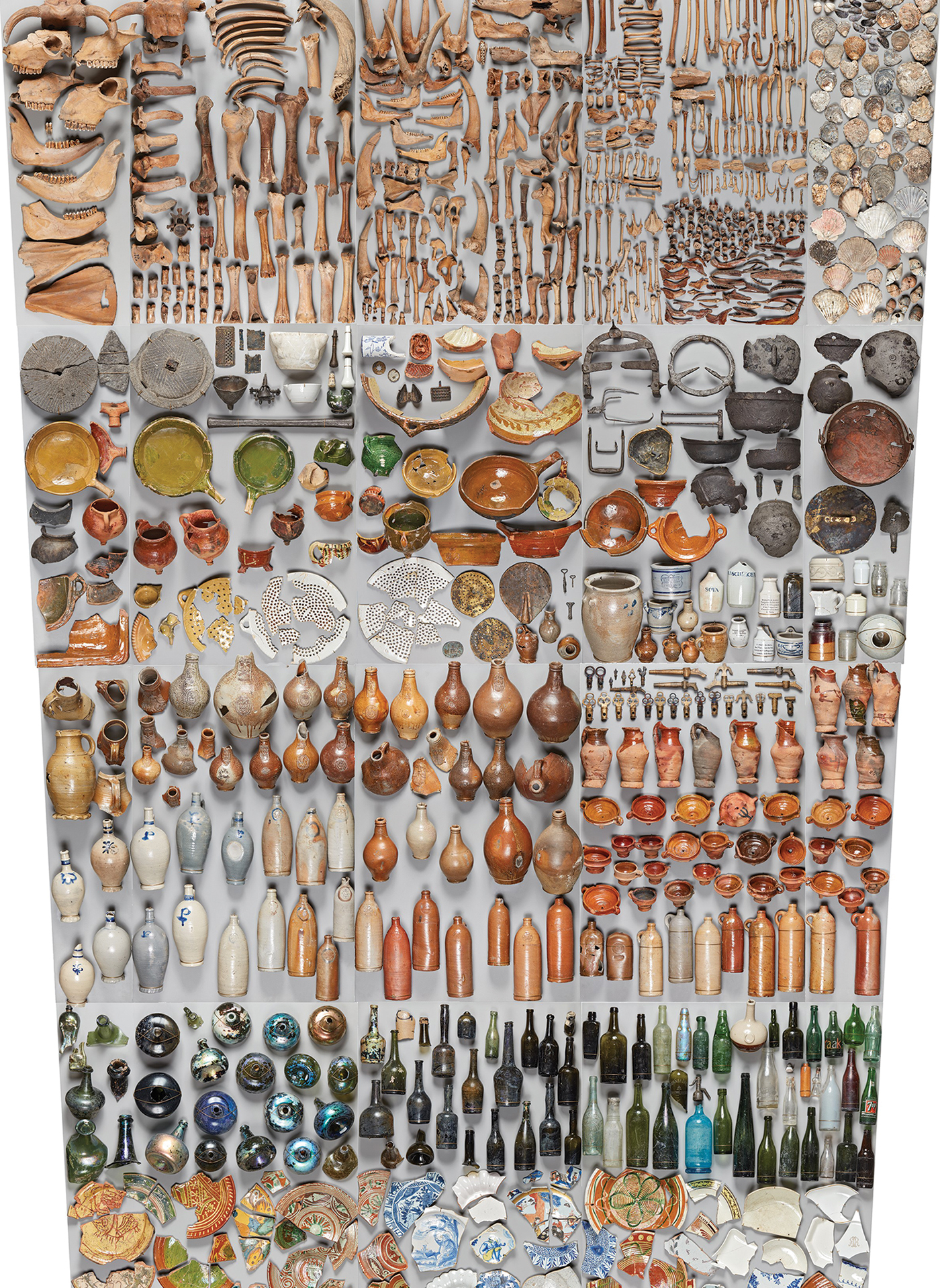

Frontispiece 1. Some of the 700 000 finds recovered by archaeologists between 2003 and 2012 during the construction of the Amsterdam North/South metro line. Construction of the stations at Damrak and Rokin involved excavation of the bed of the Amstel River, revealing an astonishing quantity and range of material culture, which included Neolithic stone axes and Bronze Age spearheads. Most of the material, however, relates to the development of the city of Amsterdam and is of late medieval and modern date, with objects ranging from ceramics to mobile phones. The finds from the investigations are on display at Rokin Station and can also be explored online at https://belowthesurface.amsterdam and via the 13 000 photographs in the catalogue Stuff by city archaeologists Jerzy Gawronski and Peter Kranendonk. Photographs by Harold Strak.

Frontispiece 2. A fresco depicting the mythological story of Leda and Zeus (in the form of a swan) is revealed during recent excavations at Pompeii. The wall painting was discovered in November 2018 in a wealthy domus in Regio V. The excavations form part of the €8.5-million, two-year ‘Great Pompeii Project’ designed to stabilise and conserve the site. After working through deposits associated with the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century excavations, which yielded numerous fragmented Roman-period finds discarded at that time, archaeologists have begun work on previously undisturbed eruption layers from AD 79. The project is the largest undertaken in the unexcavated area of Pompeii for over 50 years. Photograph by Cesare Abbate/ANSA.

Pompeii resurgent

![]() 2018 was a good year for Pompeii. After several years of bad news stories about collapsing structures and the closure of parts of the city to the public, the last 12 months have witnessed a stream of positive press coverage. Particularly high-profile stories included the discovery of an unfortunate Pompeian, asphyxiated and then pinned down under a large stone thrown during the eruption, and a charcoal graffito that has reopened debate about the exact date of the city's demise—late August or October/November? But news of other discoveries and developments in and around the city has come thick and fast. Some of that work has resulted from attempts to combat illicit excavations in the vicinity of Pompeii. Investigations north of the city at a site disturbed by looters, for example, have identified the stable block of a suburban villa, including evidence for three horses, plus saddles and harnesses, carefully recovered using the ‘Fiorelli process’ (pouring plaster into the cavities left in the volcanic deposits by the decomposition of organic materials).

2018 was a good year for Pompeii. After several years of bad news stories about collapsing structures and the closure of parts of the city to the public, the last 12 months have witnessed a stream of positive press coverage. Particularly high-profile stories included the discovery of an unfortunate Pompeian, asphyxiated and then pinned down under a large stone thrown during the eruption, and a charcoal graffito that has reopened debate about the exact date of the city's demise—late August or October/November? But news of other discoveries and developments in and around the city has come thick and fast. Some of that work has resulted from attempts to combat illicit excavations in the vicinity of Pompeii. Investigations north of the city at a site disturbed by looters, for example, have identified the stable block of a suburban villa, including evidence for three horses, plus saddles and harnesses, carefully recovered using the ‘Fiorelli process’ (pouring plaster into the cavities left in the volcanic deposits by the decomposition of organic materials).

Meanwhile, within the city, a series of buildings have reopened to the public following restoration, including the House of the Ceii, the House of Julia Felix, the House of the Large Fountain, the House of the Anchor and the Temple of Isis. Most recently, last month, the Schola Armaturarum was also reopened for guided visits. The schola, probably the headquarters of a military association, has had an eventful history. Buried by the eruption of AD 79, it was excavated in 1915–1916, only to be badly damaged by Allied bombs in 1943. Rapidly reconstructed, parts of the building then collapsed in 2010, focusing international attention on the scale of the challenge of protecting Pompeii. The collapse revealed the multiplicity of issues threatening the city's fabric including inadequate drainage, inappropriate materials used during earlier reconstruction work and the weight of unexcavated ground pressing against the buildings. In January 2019, Pompeii's Director General, Massimo Osanna, declared the (ongoing) restoration and reopening of the schola as ‘a symbol of redemption’ and a sign of hope for the future of the site as a whole. Indeed, related work, as part of the Great Pompeii Project, to deal with issues of drainage and slope stabilisation along the excavation fronts, represents the largest-scale archaeological intervention at the site in half a century. This has involved excavating through the debris of earlier excavations (including the recovery of many broken artefacts presumably discarded as incomplete by the original excavators) down to previously undisturbed layers. The latter have yielded a wealth of discoveries, including new wall paintings (see Frontispiece 2), which can now be expertly excavated, conserved and researched using the latest technology. Pompeii is once again back in the news for all the right reasons.

The story of Pompeii's demise has always overshadowed that of its origins. Understandably, the city's destruction has mesmerised archaeologists and the public alike, but the desire to preserve the Roman structures has also made it difficult to get down to the earlier layers of activity beneath. Where this has been achieved, however, the story of early Pompeii sheds light on the cultural complexity of the Italian peninsula, and the wider Mediterranean, during the mid first millennium BC. A new temporary exhibition, ‘Pompeii and the Etruscans’, installed in the city's Large Palaestra, focuses on precisely this period. The displays include finds from across Campania and set the foundation of Pompeii, c. 600 BC, in this regional context, emphasising links with contemporaneous Greek and Etruscan settlements. The latter, in particular, are illustrated through the display of weapons and Etruscan ritual vessels from recent excavations at the Fondo Iozzino sanctuary, near Pompeii's port. Firmly fixed in the popular imagination as a Roman city and largely defined by its destruction, this new exhibition characterises the first Pompeii as an ‘Etruscan city in a multi-ethnic Campania’.

Roma Universalis

![]() At the time of the foundation of Pompeii, the settlement called Rome on the banks of the Tiber was still only a modest place, little different from a dozen others across central Italy. Eight centuries later, c. AD 200, under the rule of the Severan emperors, the city controlled a huge empire stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia. ‘Roma Universalis: the Empire and the Dynasty from Africa’ is a new temporary exhibition that tells the story of the Severans and the Severan Age (c. AD 193–235). It begins, in the Colosseum, with a gallery of marble portraits of these emperors and their relatives: Septimius Severus, Julia Domna, Caracalla et al. (Figure 1). Having introduced the protagonists, attention turns to thematic displays documenting the developments of the period, including reforms of the army and of coinage, religious change and the increasingly hands-on state management of Rome's food supply (it was during this period that some 50 million empty Spanish oil amphorae were systematically dumped next to the Tiber to create the 35m-high artificial hill known as Monte Testaccio). But despite all of those innovations, these were turbulent times. The first Severan emperor, Septimius Severus, had fought his way to power in a civil war and fully recognised the importance of the legions for his personal position, for internal control of the empire and for its external security. Tellingly, new fortresses were constructed not only on distant frontiers such as at Singara (Sinjar) in Iraq, but also at the centre of the empire, a few kilometres south of Rome.

At the time of the foundation of Pompeii, the settlement called Rome on the banks of the Tiber was still only a modest place, little different from a dozen others across central Italy. Eight centuries later, c. AD 200, under the rule of the Severan emperors, the city controlled a huge empire stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia. ‘Roma Universalis: the Empire and the Dynasty from Africa’ is a new temporary exhibition that tells the story of the Severans and the Severan Age (c. AD 193–235). It begins, in the Colosseum, with a gallery of marble portraits of these emperors and their relatives: Septimius Severus, Julia Domna, Caracalla et al. (Figure 1). Having introduced the protagonists, attention turns to thematic displays documenting the developments of the period, including reforms of the army and of coinage, religious change and the increasingly hands-on state management of Rome's food supply (it was during this period that some 50 million empty Spanish oil amphorae were systematically dumped next to the Tiber to create the 35m-high artificial hill known as Monte Testaccio). But despite all of those innovations, these were turbulent times. The first Severan emperor, Septimius Severus, had fought his way to power in a civil war and fully recognised the importance of the legions for his personal position, for internal control of the empire and for its external security. Tellingly, new fortresses were constructed not only on distant frontiers such as at Singara (Sinjar) in Iraq, but also at the centre of the empire, a few kilometres south of Rome.

At the city of Rome itself, Septimius Severus and his successors instigated an extensive programme of construction resulting in an architectural legacy still visible today. ‘Roma Universalis’ innovatively leads the visitor out from the Colosseum displays into the Forum and up onto the Palatine Hill to explore monuments built or renovated by the Severan emperors. This route includes ‘old favourites’, such as the Arch of Septimius Severus, as well as recently excavated and newly accessible areas. The latter includes sections of the Temple of Peace and the remains of the monumental marble opus sectile floor of its cult chamber. Also newly accessible are the so-called Baths of Elagabalus. Although this bathing complex, in fact, is much later than the reign of the eccentric young Severan emperor Elagabalus, the recent excavations have revealed a long history of activity on this site stretching back to Archaic times. For the purposes of the exhibition, however, the Severan connection takes precedence. This focuses on a courtyard building of the early third century AD and a haul of broken sculptural pieces of Severan date, recovered from much later deposits at the site, which hint at a previously unexpected public function for this building. The marble portraits form a key part of the exhibition and are temporarily on display in the ‘Temple of Romulus’, complementing those in the Colosseum. All of these portraits of the Severan dynasty are impressive pieces of art, expertly and beautifully displayed, but largely to be appreciated in terms of a traditional connoisseurship. There is no hint, for example, that such marble busts were once painted. This is particularly striking as the ‘whiteness’ of displays of classical sculpture has been increasingly criticised, and several recent exhibitions and displays have sought to address issues of colour in the past and its legacy in the present. Given the subject matter of the exhibition—an African dynasty—some acknowledgement of colour would have been welcome.

‘Roma Universalis’ examines the Severan period on its own terms, without the weight of knowledge of the military and economic chaos that was to follow. In this view, the four decades of the Severan age represent something of a renaissance: military conquests, economic stability and the flourishing of culture and religion. The defining event of this period, for the exhibition at least, came on 11 July AD 212 when the emperor Caracalla issued an edict granting Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. “In this way”, declares the introduction to the exhibition guide, “the age of the Severans fulfilled the universalist and cosmopolitan premises with which Augustus had founded the Empire two centuries earlier”. This is the universalism that lends the exhibition its name, but as a theme it raises questions. First, changes in legal status rarely translate into clear archaeological horizons; how might this new political community be seen in terms of material culture, other than via the scrap of papyrus, dated to AD 215, which provides some of the Edict's legal wording? The exhibition's promotional video (https://youtu.be/AMRyAUu3Yxo; also displayed on a small screen tucked away next to the gift shop) relates how the extension of citizenship meant that people across the empire shared the same legal status; it is illustrated by video clips hinting at ethnic and cultural diversity today, perhaps in Rome, perhaps in North Africa or the Eastern Mediterranean. This empire of new citizens, it implies, did not involve cultural homogenisation (‘Romanisation’), but rather cosmopolitanism—a single community incorporating great ethnic, cultural and religious differences. The exhibition itself, however, does not develop this theme of diversity in any depth. By and large, the objects on display and the places that the Forum/Palatine route links together are concerned with the imperial family, with elite culture more generally and the monumental centre of empire. This is a shared elite culture rather than cosmopolitan diversity. There are some hints of ‘otherness’, some non-Romans, principally in the form of defeated Parthians on the Arch of Septimius Severus. What is largely missing, however, are the new citizens of this universal empire—the 50 million or so non-elite inhabitants of the Roman world. Walking around the Colosseum and Forum, one gains an impression of greater diversity among the modern-day visitors than in the empire on display (although with 7.4 million tourists from around the world passing through the Colosseum turnstiles in 2018, perhaps that is to be expected).

Figure 1. Marble bust of Septimius Severus on display at the Colosseum, ‘Roma Universalis’ exhibition. Photograph by C. Pescatori.

Another question about this universalism concerns its worth. For centuries, citizenship had been used to afford privilege to a select group. The extension of citizenship to all free men (i.e. not women, slaves or those from beyond the imperial frontiers) therefore abolished a fundamental legal distinction. But those new rights were tempered by other developments, including the growing emphasis on social rank, increasingly polarised between high (honestiores) and low (humiliores) status, which would come to dominate the late antique world. Citizenship was not worth what it once was.

A final question concerns the significance of this Roman universalism today. In positioning Caracalla's Edict as the fulfilment of Augustus’ vision of empire, the exhibition can be seen as the logical follow-up to the ‘Augusto’ exhibition, which marked the bi-millennium of that emperor's death in AD 14. Both exhibitions represent something of a revival of fortunes for figures and regimes once considered absolutist or corrupt, and which have been used actively to advance political agendas. As if to make the point, ‘Roma Universalis’ features several plaster models originally created for display at the ‘Mostra Augustea della Romanità’ of 1937–1938, including one of the Arch of Septimius Severus (Figure 2). Divorced from the highly charged political context of their creation, these are simply illustrative models. But they also serve as a reminder of the ways in which archaeology, and the Roman past in particular, has been mobilised for political ends before. ‘Roma Universalis’ hints at its own political potential—for example, human rights and multiculturalism—but it does not tackle this head on. Given the heightened political tensions of our own troubled times, and the ghosts of European archaeology's earlier political entanglements, perhaps any more overt treatment might have been seen as ‘too political’. And yet there is also a danger in not being explicit about the intended message of an exhibition showcasing the ‘achievements’ of a transcontinental empire headed by an authoritarian leader, backed by the military.

‘Roma Universalis’ continues until 25 August 2019 and is accompanied by two publications, both beautifully designed: a short bilingual guide and, as traditional for Italian exhibitions, a more heavyweight scholarly tome.Footnote 1 The latter features contributions that significantly expand the exhibition's coverage, particularly in relation to the situation outside Rome. The newly opened areas of the Forum and the Palatine, so neatly integrated into the exhibition, are intended to remain permanently accessible.

Figure 2. Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum (model), exhibited at the ‘Mostra Augustea della Romanità' (1937–1938). Patinated alabaster gypsum; 1.14 × 1.44 × 0.84m; scale 1:20. Museo della Civiltà Romana (inv. MCR 468), Rome. Photograph by Z. Colantoni.

In this issue

![]() The current issue, as ever, features a variety of archaeological research, ranging in time from the Late Pleistocene to the twentieth century, and around the globe from the High Arctic to Australia. One emergent theme concerns the lengths to which past humans have gone to acquire raw materials. Pargeter and Hampson examine evidence from rockshelters in Lesotho for the preferential selection of quartz for tool production. The availability of a range of other lithic materials suggests quartz—unpredictable to work but possessing other unusual properties—was actively sought out. It was, however, locally available, and other human societies have had to look much farther afield for just the right stone. It has long been known, for example, that Stonehenge's bluestones were sourced from the Preseli Hills, over 200km away in south-west Wales. Mike Parker Pearson and colleagues reported on the excavation of one of these megalith quarry sites in Antiquity 89.Footnote 2 In this issue, they present the results of their investigations of another quarry site, Carn Goedog, including new dates linking the extraction of stone pillars to the first stage of the construction of Stonehenge c. 3000 BC.

The current issue, as ever, features a variety of archaeological research, ranging in time from the Late Pleistocene to the twentieth century, and around the globe from the High Arctic to Australia. One emergent theme concerns the lengths to which past humans have gone to acquire raw materials. Pargeter and Hampson examine evidence from rockshelters in Lesotho for the preferential selection of quartz for tool production. The availability of a range of other lithic materials suggests quartz—unpredictable to work but possessing other unusual properties—was actively sought out. It was, however, locally available, and other human societies have had to look much farther afield for just the right stone. It has long been known, for example, that Stonehenge's bluestones were sourced from the Preseli Hills, over 200km away in south-west Wales. Mike Parker Pearson and colleagues reported on the excavation of one of these megalith quarry sites in Antiquity 89.Footnote 2 In this issue, they present the results of their investigations of another quarry site, Carn Goedog, including new dates linking the extraction of stone pillars to the first stage of the construction of Stonehenge c. 3000 BC.

Two other articles document the search for raw materials on scales even more epic. In 1841, the whaling ship Connecticut set out from the east coast of North America on a two-year whale hunt that took the vessel halfway around the world. Paterson et al. discuss newly identified inscriptions in the Dampier Archipelago off the north-west coast of Australia, made by the ship's crew on rock surfaces already richly marked with motifs by indigenous Australians. But perhaps the most astonishing example featured here of the lengths to which past humans have gone in search of the right material for the job takes us to the Arctic island of Zhokhov. Here, Pitulko et al. report on the provenancing of obsidian objects dating to 8000 BP. The source of the obsidian is traced to Lake Krasnoe, approximately 1500km away across the Siberian Plain, leading the authors to consider the technologies, such as the dog-sled, that facilitated this ‘super-long-distance Mesolithic exchange network’.

Another group of articles emerges around the use of radiocarbon dating to modify chronological frameworks based on material cultural styles. Zazzo et al. present a suite of new dates for monumental funerary complexes of deer stones and khirgisuurs in Mongolia. The authors use their new high-precision chronology to assess different models of Late Bronze Age socioeconomic organisation and the scale of human and animal resources that these monuments represent. Meanwhile, Duffy et al. also use radiocarbon dating of Bronze Age burials in Hungary to question the idea of regional depopulation in the mid second millennium BC; our archaeological fascination with tells, they argue, has led us to overlook the role of ‘flat’ sites. Farther south, in Croatia, Zavodny et al. also make use of a new set of radiocarbon dates of burials in order to evaluate a traditional ceramics-based chronology; their revised dating indicates much greater variability in the selection of grave goods, directing the authors to an alternative narrative of the emergence of the Iapodian culture. Another article dealing with radiocarbon—and how its results relate to other forms of dating—returns us to the thorny question of the date of the Bronze Age eruption of Thera, a topic explored in previous issues of Antiquity.Footnote 3 McAneney and Baillie move the story in a new direction. For some time, radiocarbon dates have pointed to the seventeenth century BC for the eruption and, especially, to a volcanic event c. 1627 BC. But through a revision of the Greenland ice-core chronology back to c. 2000 BC, the authors identify a more probable explanation for the 1627 BC event—a volcanic eruption 9000km away in Alaska. If correct, one of the most familiar of radiocarbon dates may not, after all, represent the Theran eruption, reopening the question of exactly when the catastrophic event really took place.

We also feature a number of other articles, including two that deal with modern perceptions of the Vikings. In 2017, the publication of an article announcing the genomic identification of a female Viking warrior instigated one of the biggest archaeology news stories of the year; the ensuing debate raised a host of questions, not only about the nature of archaeological interpretation but also broader issues of identities, past and present, and the role of the public, press and social media. The authors of that article elaborate on their original short publication with a fuller account of the archaeological evidence and their analysis; they also step back to reflect on the wider controversies that their identification provoked. Meanwhile, the recent redesign of the Viking gallery at the National Museum in Copenhagen has been the subject of controversy. Reviewing the new displays, Søren Sindbæk explores what they say about the challenges faced by museums generally and about the representations of the Vikings in particular. We also have articles on Egyptian animal mummies (Atherton-Woolham et al.), hydraulic technology on the periphery of the Hellenistic world (Vranić), newly discovered bronze Dong Son drums from Timor-Leste (Oliveira et al.) and a unique archaeobotanical assemblage from Abbasid-period Jerusalem (Amichay et al.).

Our final article, by Grzegorz Kiarszys, focuses on the archaeology of the recent past, with an analysis of nuclear warhead storage sites in Poland. As a child I grew up not so far from a U.S. air force base in southern England; if the Cold War had got hot, we would have been some of the first to (briefly) know about it. But while our young minds pondered the when of Armageddon, no one gave any thought to the question of the where; specifically, where, from behind the Iron Curtain, the Soviet missiles may have come; frankly, that knowledge would have offered little comfort. The answer, however, we now know, lies in the forests of western Poland. Kiarszys draws together declassified intelligence and remotely sensed imagery to investigate three of the weapon storage sites and to fill in the history of the ‘silent’ 23 years between 1969 and 1992. He ends with a plea for the recognition and protection of these sites as a form of shared heritage that speaks to contemporary identities across Eastern Europe and beyond. But lest anyone thought that the ‘Cold War as heritage’ meant we could stop worrying and learn to love the bomb, with impeccable timing, President Putin announced his 2019 New Year's gift to the Russian nation: a new intercontinental, hypersonic nuclear missile system. Assuming that, like its Cold War predecessors, the new Avangard system is never used, and we all live to tell the tale, might we be discussing it as archaeological heritage 50 years hence?

Antiquity updates

Over the past year, the Antiquity reviews section and Project Gallery have been in the capable hands of Dan Lawrence. Alas, the recent award of a large European grant—combined with the limited number of hours in a day—means that Dan needs to step away from Antiquity to focus on setting up his new project. We wish him well with his new venture. You can find Dan's final New Book Chronicle at the end of this issue. Meanwhile, we are delighted to introduce our new Reviews Editor, Claire Nesbitt. Claire has worked on a variety of periods, regions and topics, from Mesolithic Scotland to Byzantine churches in Turkey, all of which will put her in good stead to deal with the range of books received for review. The existing contact addresses remain unchanged; Claire can be contacted via email at reviews@antiquity.ac.uk, and books for review should continue to be sent to the same Durham postal address as before. Like Dan, Claire will also cover the Project Gallery remit, where a couple of changes are also afoot. From 2019, the Project Gallery will be accepting articles up to 1500 words in length and, to bring them into line with our research articles, these will now be handled via the ScholarOne submissions system (https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/aqy); finally, Project Gallery contributions will also be subject to external peer review. With these changes, we hope to provide a better experience for both our authors and readers.

In signing off, the annual reminder that Antiquity will be attending several conferences during the year, including SAA in Albuquerque in April, EAA in Bern during September and TAG in London just before Christmas. We will also be supporting a number of smaller conferences, workshops and meetings with various student prizes and bespoke free-to-access article collections. If you are organising an event in 2019, do get in touch via assistant@antiquity.ac.uk and let us know about it!