Introduction

Suicide leads to roughly 800 000 deaths every year and is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15–29 in the world (World Health Organization, 2018). Suicidal behaviours, including suicidal thought, suicide plan and suicide attempt, are prevalent in adolescents and have been reported as the strongest predictor of future suicide attempts or suicide death (Park et al., Reference Park, Ryu, Han, Kwon, Kim, Kang, Yoon, Cheon and Shin2010; Vera et al., Reference Vera, Reyes-Rabanillo, Huertas, Juarbe, Perez-Pedrogo, Huertas and Pena2011; Zhang and Zhou, Reference Zhang and Zhou2011; Hamza et al., Reference Hamza, Stewart and Willoughby2012; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012; Runeson et al., Reference Runeson, Haglund, Lichtenstein and Tidemalm2016). The overall prevalence of suicidal thought during the past year among adolescents in 32 low- and middle-income countries was 16.2% (Britt et al., Reference Britt, Geneviève, Mariane and Elgar2016). In the US Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 13.6% of adolescent students ever made a specific plan to attempt suicide during the past 12 months (Kann et al., Reference Kann, McManus, Harris, Shanklin, Flint, Queen, Lowry, Chyen, Whittle, Thornton, Lim, Bradford, Yamakawa, Leon, Brener and Ethier2018). The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempt in youth was about 3.2–15.6% (Brausch and Gutierrez, Reference Brausch and Gutierrez2010; Taliaferro et al., Reference Taliaferro, Muehlenkamp, Borowsky, McMorris and Kugler2012; Zetterqvist et al., Reference Zetterqvist, Lundh and Svedin2013; Price and Khubchandani, Reference Price and Khubchandani2016).

Suicidal behaviours are multifactorial. Many studies have demonstrated that mental health problems, substance use, genetic and biological factors, poor physical health or physical disability, and family–environmental factors are associated with increased risk of suicidal behaviours in adolescents (Gould et al., Reference Gould, Greenberg, Velting and Shaffer2003; Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Goldstein and Brent2006; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen, Liu, Wang and Jia2017b). It is well known that depression increases risk of suicidal behaviours (Torpy et al., Reference Torpy, Lynm and Glass2005; Liu, Reference Liu2006; Nanayakkara et al., Reference Nanayakkara, Misch, Chang and Henry2013). Impulsivity, a psychological diathesis towards rapid and unplanned reactions to stimulation regardless of the outcome, is another well-known psychological risk factor of suicidal behaviours (Dougherty and Dm, Reference Dougherty and Dm2009; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012). Interparental conflicts, poor economic status and family suicidal history are major family risk factors of suicidal behaviours in adolescents (McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013; Lopez-Castroman et al., Reference Lopez-Castroman, Guillaume, Olie, Jaussent, Baca-Garcia and Courtet2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen, Liu, Wang and Jia2017b).

Exposure to suicidal behaviours (ESB) has been identified as a potential risk factor of adolescent suicidal behaviours. However, findings are not consistent across previous studies. Some studies reported a positive association between ESB and adolescent suicidal behaviours (Nanayakkara et al., Reference Nanayakkara, Misch, Chang and Henry2013; Abrutyn and Mueller, Reference Abrutyn and Mueller2014; Song et al., Reference Song, Kwon and Kim2015) but some studies did not (Watkins and Gutierrez, Reference Watkins and Gutierrez2005; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Stewart, Ho, Rao and Lam2005), and even negative associations were reported (Mercy et al., Reference Mercy, Kresnow, O'Carroll, Lee, Powell, Potter, Swann, Frankowski and Bayer2001). Inconsistent findings are possibly due to differences in measures used to assess ESB, study methods and/or target populations. For example, some studies defined ESB as exposure to either suicide death or attempt (Mercy et al., Reference Mercy, Kresnow, O'Carroll, Lee, Powell, Potter, Swann, Frankowski and Bayer2001; Jegannathan and Kullgren, Reference Jegannathan and Kullgren2011; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013). Suicidal behaviours have been considered a spectrum from suicidal thought, plan, attempt to death, although there are overlaps between different suicidal behaviours (Turecki and Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016). Hence, exposure to suicide death and attempt may have different effects on adolescent suicidal behaviours and it may be plausible to examine the two types of exposure separately.

Different exposure sources of suicide attempt or death may have various effects on suicidal behaviours. According to a recent literature review (Stack and Niederkrotenthaler, Reference Stack and Niederkrotenthaler2017), more than 150 studies on suicidal exposure in the media have been published. However, the associations between suicidal exposure in the media and its imitation effects on suicidality in previous studies are mixed. Studies on exposure to other individuals’ (family, friends or acquaintances) suicidal behaviours in the real life are limited, especially in adolescents.

Studies have indicated that family history of suicidal behaviours is an important risk factor for adolescent suicide (McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013; Lopez-Castroman et al., Reference Lopez-Castroman, Guillaume, Olie, Jaussent, Baca-Garcia and Courtet2015). Although the mechanism is not clear, suicide bereavement, family–environmental factors, genetic factors may play important roles (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen2002; Tidemalm et al., Reference Tidemalm, Runeson, Waern, Frisell, Carlstrom, Lichtenstein and Langstrom2011; Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Stone and Hankin2018). One recent literature review (Maple et al., Reference Maple, Cerel, Sanford, Msw and Jordan2016) concluded that suicidal risk increased among adolescents beyond exposure from family numbers (i.e. friends, schoolmates or acquaintances) possibly due to imitation (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Rees, Posick and Zimmerman2016). However, previous studies of suicide exposure did not distinguish between the effects of exposure to a family member's suicidal behaviours and exposure to friends’/close acquaintance’ suicidal behaviours (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Stewart, Ho, Rao and Lam2005; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013), and did not examine the effects of ESB in both relatives and friends/close acquaintances (Nanayakkara et al., Reference Nanayakkara, Misch, Chang and Henry2013; Abrutyn and Mueller, Reference Abrutyn and Mueller2014; Song et al., Reference Song, Kwon and Kim2015).

Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies have been specifically conducted to examine the effects of ESB on suicidal behaviours in Chinese adolescents. In the current study of a large sample of Chinese students, we aimed to examine the associations between ESB of relatives or friends/close acquaintances and suicidal behaviours in adolescents. Our hypotheses were (1) either ESA or ESD was associated with increased risks of suicidal behaviours in adolescents, (2) ESB of relatives and friends/close acquaintances might have different impacts on adolescent suicidal behaviours, and (3) adolescents who were exposed to suicidal behaviours of both relatives and friends/close acquaintances were at higher risks of suicidal behaviours than those who were exposed to suicidal behaviours of relatives or friends/close acquaintances alone.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Shandong Adolescent Behavior and Health Cohort (SABHC) is a 3-year ongoing longitudinal study of adolescent behaviours and health in Shandong, China. In November 2015, the baseline survey of SABHC was conducted in five middle and three high schools from three counties of Shandong Province, China. Shandong, a typical province in social and economic status, is located in the east coast of China and the lower reaches of the Yellow River and has a total population of 97.89 million (Shandong Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2015). Based on the geographic location, social economic status, potential representativeness of adolescent students in the region, prior study collaboration and feasibility to conduct the study, we first selected Zoucheng, Yanggu and Lijin county, which are located in the south, west and northeast of Shandong, respectively. With consideration of representatives of the schools and convenience, we then selected five middle schools and three high schools from the three counties. With consideration of the sample size and the feasibility for at least 2 years of follow-up, we finally selected all seventh-graders and tenth-graders and half of 8–9th graders and 11th-graders from each target school using classes as sampling units. All students in the selected classes were invited to participate in the survey. Detailed sampling and procedure have been published elsewhere (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang, Bo, Zhang, Qi, Liu and Jia2017; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen, Bo, Fan and Jia2017a, Reference Liu, Chen, Liu, Wang and Jia2017b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen, Bo, Chen, Li, Lv, Jia and Liu2018).

A self-administered Adolescent Health Questionnaire (AHQ) (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao, Jia and Buysse2008; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao and Jia2015) was used to assess suicidal behaviours in the last year, history of ESB, mental health and family environment. During regular school hours, trained master-level public health workers administered the AHQ to all students in the sampled classes from each school at the same time. Before filling out the questionnaire, participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, the survey was anonymous and they were asked to answer questions following instructions. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Shandong University School of Public Health and target schools.

Measures

Suicidal behaviours

Following Silverman et al. (Reference Silverman, Berman, Sanddal, O'Carroll and Joiner2007), suicidal thought, plan and attempt during the past year were assessed by ‘Have you ever seriously thought about suicide in the last year?’, ‘Have you ever made a specific plan to suicide in the last year?’ and ‘Have you ever tried to suicide in the last year?’ respectively. All of the questions had a ‘yes/no’ answer. If a respondent answered ‘yes’ on the question, he or she was considered to have the behaviour. Cronbach's α was 0.66 with the current sample.

Exposure to suicide attempt or death

ESA was assessed by two questions: (1) ‘Has someone in your family (including parents, grandparents, siblings and other relatives) ever attempted suicide but survived?’, (2) ‘Has a friend or close acquaintance ever attempted suicide but survived?’. ESD was assessed by two similar questions: (1) ‘Has someone in your family (including parents, grandparents, siblings and other relatives) died by suicide?’, (2) ‘Has a friend or close acquaintance died by suicide?’. Participants were asked to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each question. Based on the answers, participants were divided into four groups: non-exposure (NE), exposure to relatives’ suicidal behaviours only (ERO), exposure to friends’/close acquaintances’ suicidal behaviours only (EFO) and exposure to both relatives’ and friends’/close acquaintances’ suicidal behaviours (ERF).

Study covariates

Adolescent and family demographical factors, which are potentially associated with suicidal behaviours and/or suicidal exposure, were selected for analyses as covariates (Torpy et al., Reference Torpy, Lynm and Glass2005; Dougherty and Dm, Reference Dougherty and Dm2009; Feigelman and Gorman, Reference Feigelman and Gorman2011; Jegannathan and Kullgren, Reference Jegannathan and Kullgren2011; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012). Adolescent factors included sex, age, self-perceived physical health (good, fair or poor), depression and impulsivity.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) was used to measure depressive symptoms during the past week. The CES-D consists of 20 questions. Each question is answered on a four-point scale: 0 = <1 day; 1 = 1–2 days; 2 = 3–4 days; 3 = 5–7 days. The total score ranges from 0 to 60. The higher the score, the higher the levels of depression. Cronbach's α was 0.88 with the current sample.

The Eysenck Junior I7 impulsiveness scale (Eysenck et al., Reference Eysenck, Easting and Pearson1984) was used to assess impulsivity regarding the ability to plan, postpone or think before acting. The scale is composed of 19 items with a modified response format that ‘1 = never or rarely’, ‘2 = sometimes’, ‘3 = often’, to ‘4 = always’. Cronbach's α was 0.92 with the current sample.

Family socioeconomic status was assessed by father's education (primary school, middle school, high school, college or above), perceived family economic status (good, fair, poor) as compared with other families in the community and parental marital status (married, divorced or widowed). School was also included as a covariate to adjust for potential confounding effects of schools that participants were attending.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to describe adolescent and family demographics. The χ 2 tests for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables were performed to examine differences in adolescents and family demographical factors between suicidal and non-suicidal adolescents. Differences in the prevalence of suicidal behaviours in the past year among four groups of participants exposed to different suicidal behaviours were examined by χ 2 tests. Fisher's exact tests were carried out when more than 20% of the cells demonstrated the expected frequency of less than five. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the associations between ESA or ESD and suicidal behaviours, respectively, adjusting for covariates (sex, age, school, self-reported physical health, depression, impulsiveness, father education, parental marital status and family economic status). All tests were two-tailed and the p < 0.05 was used for statistical significance threshold. All statistical analyses were performed by IBM SPSS20.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 12 301 students were sampled for the baseline survey, and 11 836 (96.2%) students returned questionnaires. Five participants returned their questionnaire without answers and were excluded from the analysis, leaving 11 831 for the analyses. Mean age was 14.97 ± 1.46 years, and 50.9% were boys. See Table 1 for participant and family characteristics by suicidal behaviours in detail.

Table 1. Sample characteristics between non-suicidal and suicidal adolescents

Prevalence of exposure to suicidal behaviors

As shown in Table 2, of the 11 831 participants, 9.4% (n = 1119) reported having exposed to suicide attempt, including 1.2% (n = 144) having exposed to suicide attempt of relatives only, 7.3% (n = 867) having exposed to suicide attempt of friends/close acquaintances only and 0.9% (n = 108) having both relatives and friends/close acquaintances who had attempted suicide. A total of 6.6% (n = 783) participants reported having exposed to suicide death, including 1.5% (n = 173) having exposed to relatives’ death by suicide, 4.2% (n = 497) having exposed to friends/close acquaintances’ death by suicide and 0.9% (n = 113) having exposed to both relatives’ and friends/close acquaintances’ death by suicide.

Table 2. Prevalence of exposure to suicide behaviours in Chinese adolescents

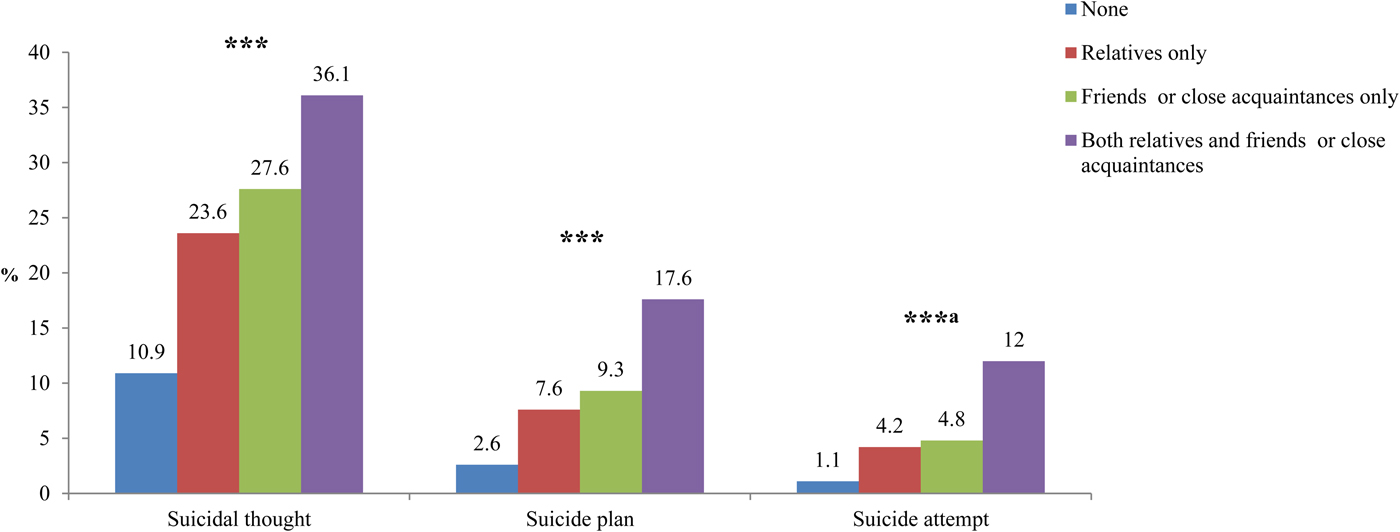

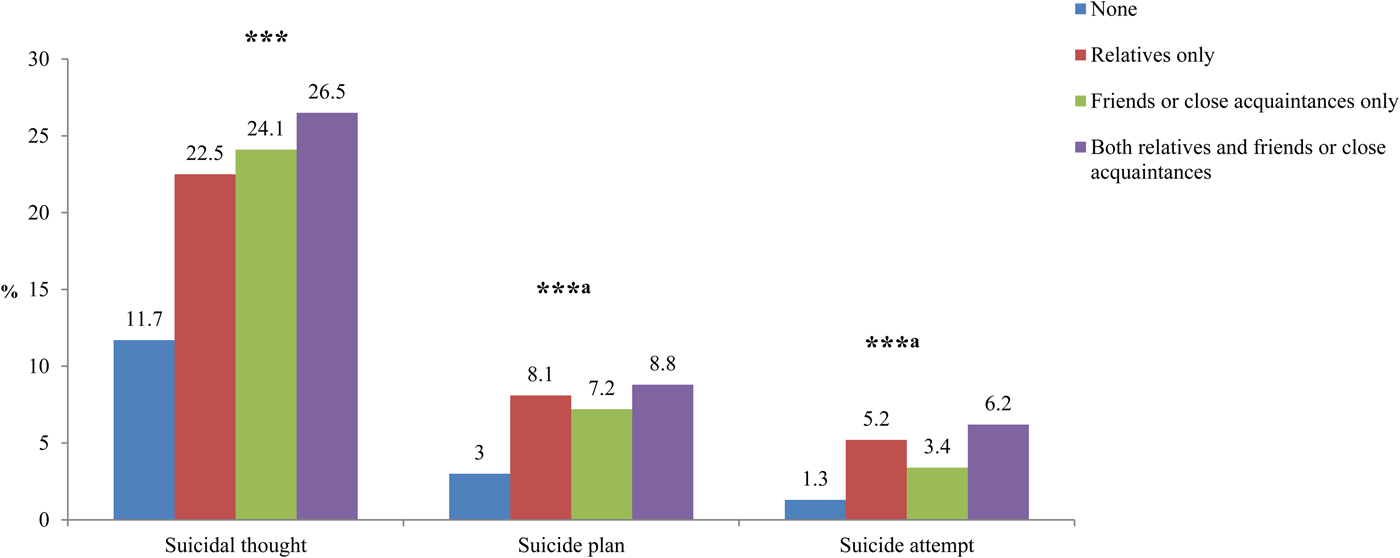

Prevalence of suicidal behaviours by ESA/ESD

The last-year prevalence rates of suicidal thought, plan and attempt were 12.5, 3.3 and 1.5%, respectively. For ESA, the prevalence rates of suicidal thought, plan and attempt during the past year were highest in ERF group (36.1, 17.6 and 12.0%, respectively), followed by EFO group (27.6, 9.3 and 4.8%, respectively) and ERO group (23.6, 7.6 and 4.2%, respectively), being lowest in NE group (10.9, 2.6 and 1.1%, respectively). There were significant differences in the prevalence of suicidal behaviours across the four groups (all p < 0.0001). Details can be seen in Fig. 1. In terms of ESD, similar trend in the prevalence of suicidal thought was observed: being highest in ERF group (26.5%), followed by EFO group (24.1%) and ERO group (22.5%), and NE group (11.7%). For suicide plan and attempt, the prevalence rates were higher in ERO group (8.1 and 5.2%) than in EFO group (7.2 and 3.4%). See Fig. 2 for details.

Fig. 1. Suicidal behaviours among Chinese adolescents exposed to suicide attempt. Note. aFisher's exact test; Note *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 2. Suicidal behaviours among Chinese adolescents exposed to suicide death. Note. aFisher's exact test; Note *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

ESA or ESD and suicidal behaviours

Tables 3 and 4 show the associations of ESA or ESD with suicidal behaviours, separately. Univariate logistic regressions indicated that ESA or ESD in relatives or friends/close acquaintances were all significantly associated with elevated risks of suicidal behaviours, respectively. After controlling for all studied adolescent and family covariates, ESA and ESD were still associated with elevated risks of suicidal thought (ESA: OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.66–2.31; ESD: OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.31–1.94), plan (ESA: OR = 2.37, 95% CI = 1.84–3.05; ESD: OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.18–2.23) and attempt (ESA: OR = 2.73, 95% CI = 1.92–3.89; ESD: OR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.18–2.82), respectively. In terms of ESA, EFO and ERF groups had significant higher risks of suicidal thought (ERF: OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.28–1.64; EFO: OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.64–2.36), plan (ERF: OR = 3.72, 95% CI = 2.04–6.78; EFO: OR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.74–3.01) and attempt (ERF: OR = 4.83, 95% CI = 2.30–10.17; EFO: OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.73–3.81), respectively. In terms of ESD, all three groups had higher risks of suicidal thought (ERF: OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.04–2.76; ERO: OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.05–2.41; EFO: OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.23–2.01), EFO group had a higher risk of suicide plan (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.07–2.32), and ERO group had a higher risk of suicide attempt (OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.39–6.34). Other odds ratios were no longer significant.

Table 3. Relationships between suicidal behaviours and exposure to suicide attempt by multiple logistic regression analyses

Adjusted ORs were adjusted for all other variables in the table and school.

a Any exposure included exposure to relatives or exposure to friends/close acquaintances.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

Table 4. Relationships between suicidal behaviours and exposure to suicide death by multiple logistic regression analyses

Adjusted ORs were adjusted for all other variables in the table and school.

a Any exposure included exposure to relatives or exposure to friends/close acquaintances.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the associations between ESA or ESD and suicidal behaviours, and the differences in the risks of suicidal behaviours in adolescents who were exposed to suicidal behaviours in family members and friends/close acquaintances. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the associations, especially in Chinese adolescents. Our major findings are (1) more than 10% of adolescents had been exposed to friends/close acquaintances’ or relatives’ suicidal behaviours, (2) ESA and ESD were both associated with adolescent suicidal behaviours, (3) adolescents who were exposed to suicide attempt of both relatives and friends/close acquaintances were at higher risks for suicidal behaviours than those exposed to suicide attempt of either relatives or friends/close acquaintances alone, (4) compared with relatives’ suicide attempt, friends/close acquaintances’ suicide attempt was more likely to be associated with adolescent suicidal behaviours.

ESA/ESD and adolescent suicidal behaviours

In the current study, ESA and ESD were both related to adolescent suicidal behaviours. The precise mechanisms are unknown, but there are potential theoretical interpretations on how exposure to suicide behaviours affects adolescent SB.

First, exposed adolescents suffered from more mental health problems than their unexposed peers because of experiencing greater pain and stress after a family member or a peer's suicidal behaviours (Brent et al., Reference Brent, Moritz, Bridge, Perper and Canobbio1996; Cerel et al., Reference Cerel, van de Venne, Moore, Maple, Flaherty and Brown2015; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Cerel and Bryan2017). However, in our multivariate logistic regressions, the associations between ESA or ESD and adolescent suicidal behaviours were still significant after controlling for depression and impulsiveness. This means the associations observed in the study cannot be explained only by mental health problems caused by suicidal behaviours in family members or friends. Other studies also found depression or impulsiveness was not distinguished between exposed group and unexposed group (Feigelman and Gorman, Reference Feigelman and Gorman2011; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013), and there was no interaction between suicidal exposure and depression (Nanayakkara et al., Reference Nanayakkara, Misch, Chang and Henry2013).

Second, elevated risks of suicidal behaviours in exposed adolescents may be due to the contagion/imitation of suicidal behaviours in adolescents (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Glaeser and Norberg2000; Gould, Reference Gould2010; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Corcoran, Keeley, Perry and Arensman2013). Namely, the knowledge of suicidal behaviours of others could provide adolescents facing difficulty with approach to problems, and they learn from suicidal behaviours to deal with the life or emotional problems. The psychological and behavioural development is still ongoing during adolescence, and it is not surprising that other's suicidal behaviours will adversely affect adolescents’ thinking and behaviour. This may explain why adolescents exposed to other individuals’ suicide attempts are at higher risks than those exposed to suicide death.

Third, family aggregation and/or genetic factors may explain high risks of suicidal behaviours in adolescents who were exposed to suicidal behaviours in family members. Other factors such as shared environment (Tidemalm et al., Reference Tidemalm, Runeson, Waern, Frisell, Carlstrom, Lichtenstein and Langstrom2011; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012; Haw et al., Reference Haw, Hawton, Niedzwiedz and Platt2013), bereavement (Pitman et al., Reference Pitman, Osborn, Rantell and King2016; Erlangsen et al., Reference Erlangsen, Runeson, Bolton, Wilcox, Forman, Krogh, Shear, Nordentoft and Conwell2017), assortative mating or relating (Joiner, Reference Joiner2003; Agerbo, Reference Agerbo2005; Liviatan et al., Reference Liviatan, Trope and Liberman2008) may also play important roles in the link between ESB and risk of adolescent suicidal behaviours. Further research is warranted to examine the biological and psychosocial mechanisms.

Exposure sources and adolescent suicidal behaviours

In this study, we found that different sources of exposure had different effects on adolescent suicidal behaviours. In terms of ESA, those exposed from friends or close acquaintances had significantly elevated risks of suicidal behaviours, but there was no significance between exposure to relatives’ suicide attempt and adolescent suicidal behaviours. This finding suggests that adolescent suicidal behaviours may be more likely to be influenced by peers’ suicidal behaviours. This finding is consistent with previous studies that the influence of friends surpassed that of family on adolescent mental and behavioural health (Crosnoe, Reference Crosnoe2000; Abrutyn and Mueller, Reference Abrutyn and Mueller2014). For example, in a study of US high school students, the authors found that recent attempt by friends was one of the strongest predictors of future suicide attempt and failed to find a significant impact of the suicide attempt in family members (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Rohde and Seeley1994). Together with other studies, it may be concluded that shared environment or imitation effect in peer model may be more dominant than genetic factors (Hazell, Reference Hazell1993; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen2002) in family model in adolescent suicidal behaviours when exposed to suicide attempt.

It should be noted that previous studies did not find consistent associations between ESB in the media and subsequent suicidality in adolescents (Amitai and Apter, Reference Amitai and Apter2012; Daine et al., Reference Daine, Hawton, Singaravelu, Stewart, Simkin and Montgomery2013; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Fu, Caine and Yip2014). In fact, some studies did not support the imitation effect of suicidal behaviours in the media (Stack, Reference Stack2005; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Metcalfe and Gunnell2011; Fu and Chan, Reference Fu and Chan2013). In the current study, we found that ESB in the real life was associated with significantly increased risk of suicidality in adolescents. This may suggest that compared with suicidal exposure in media (e.g. newspaper, television and internet), exposure in real life may contribute to higher risk of suicidal behaviours than media exposure among adolescents. These adolescents who have been exposed to other individuals’ suicidal behaviours in the real life should be given more attention and professional help to prevent adolescent suicidal behaviours.

Study limitations

The following limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, all the data used in the study were measured by self-report, which might lead to recall bias. Second, this is a cross-sectional study, and we did not collect data on the timing of suicidal exposure, which made it difficult to determine the causal relationship between ESB and suicidal behaviours. Our ongoing longitudinal data collection and analyses will help clarify the causal relationship. Third, this study did not distinguish between friends and close acquaintances and between family members and non-family relatives, and it could be a subject of future research. Fourth, although this sample is large, it is not randomly selected for feasibility to conduct the study. It is unknown whether these findings from the sample can be generalised to adolescents in other regions.

Conclusions

Although lots of studies have been conducted in the suicidal exposure in the media, little attention has been paid to the suicidal exposure in the immediate social networks such as family and peers. The current study indicated that suicidal behaviours of family or friends/close acquaintances significantly increased the risks of adolescent suicidal behaviours, and their effects on adolescent suicidal behaviours were different. Psychosocial intervention and mental health education for adolescents exposed to suicidal behaviours in the real life and social media like Blue Whale challenge may have important public health implications to prevent self-harm and suicide in youth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CDC and Education Bureau staffs of Lijin, Yanggu and Zoucheng and all teachers of participating schools for their help with data collection, and all students for their voluntarily participating in the study.

Financial support

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81573233), and Shandong University School of Public Health Third Level Discipline Infrastructure Project Fund (grant number 2017-08).

Conflict of interest

None.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact Dr Cun-Xian Jia at jiacunxian@sdu.edu.cn for data supporting the findings of the study.