Black Lives Matter (BLM) has been a visible and influential social movement since the acquittal of George Zimmerman in 2013 for his role in the death of Trayvon Martin, an African-American teenager. Since then, the movement has staged both small and large demonstrations around the United States and beyond, responding principally to the deaths of Black and African people at the hands of police (Williamson, Trump, and Einstein Reference Williamson, Trump and Einstein2018). BLM reached its zenith (so far) in 2020, when protests erupted after the murder of George Floyd, an African-American man, by a white Minneapolis police officer. The protests pushed an agenda that demanded institutional change (such as calls to “defund the police”), sought responsiveness from candidates pursuing election to public office, and exhibited a multiracial coalition in the streets (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2021, 198–99). Following these events, BLM was hailed as one of the largest and broadest social movements in American history (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel Reference Buchanan, Bui and Patel2020; Putnam, Chenoweth, and Pressman Reference Putnam, Chenoweth and Pressman2020). The size of the movement—along with the fact that it squarely confronts an issue that has been at the center of American politics for the nation’s entire history—makes it an urgent subject for scholarly research.

Individual activists who participate in BLM protests are a critical part of the movement, as they volunteer their time and spend their own money, as well as assume risks to their personal health, safety, and liberty (Cobbina et al. Reference Cobbina, LaCourse, Brooke and Chauduri2021). Research on BLM has begun to examine the role of individual activists in the movement. Studies have reported on the demographics of BLM protesters (Baskin-Sommers et al. Reference Baskin-Sommers, Simmons, Conley, Chang, Estrada, Collins and Pelham2021; Fisher Reference Fisher2019; Heaney Reference Heaney2018; Hope, Keels, and Durkee Reference Hope, Keels and Durkee2016; Milkman Reference Milkman2017), how plans for future participation are affected by the experience of repressive policing (Cobbina et al. Reference Cobbina, Chaudhuri, Rios and Conteh2019), and how social media use, social network ties, and other protest structures affect participation in the movement (Acheme and Cionea Reference Acheme and Cionea2022; Hong and Peoples Reference Hong and Peoples2020; Lake, Alson, and Kan Reference Lake, Alson and Kahn2021). While these prior studies are informative, they have been considerably limited in scope. For example, they have been based on surveys conducted only at a single BLM event (Cobbina et al. Reference Cobbina, LaCourse, Brooke and Chauduri2021; Fisher Reference Fisher2019; Heaney Reference Heaney2018), drawn on small samples (Cobbina et al. Reference Cobbina, Chaudhuri, Rios and Conteh2019; Hong and Peoples Reference Hong and Peoples2020), or focused on a narrow population such as college students (Hope, Keels, and Durkee Reference Hope, Keels and Durkee2016; Lake Reference Lake, Alson and Kahn2021), adolescents (Baskin-Sommers et al. Reference Baskin-Sommers, Simmons, Conley, Chang, Estrada, Collins and Pelham2021), high-profile activists (Milkman Reference Milkman2017), or Nigerian immigrants (Acheme and Cionea Reference Acheme and Cionea2022).

In order to appreciate the full impact of BLM and its place in the contemporary politics of the United States, it is necessary to know more about the activists who compose the movement. Who are these activists—beyond basic demographics related to age, gender, and race? What were their first steps into grassroots activism? How do BLM activists compare with those in other social movements? Where do they fit into broader political communities? Together these questions amount to asking: what is the nature of BLM’s niche?

Within the study of social movements, a niche is understood as a point in a multidimensional space that is composed of the characteristics of a movement’s members or supporters (Stern Reference Stern1999). While that space has a potentially infinite number of dimensions, scholars typically select a handful of dimensions (McPherson Reference McPherson1983, 520) that are theoretically relevant to understanding the movements in question, such as the political views of adherents or preferences over protest tactics. In seeking to discern the nature of BLM’s niche, this article has three primary objectives. First, it seeks to describe the niche with respect to dimensions that are important for understanding the movement. Second, it aims to infer whether BLM differs from other social movements in its environment with respect to these key aspects. Third, it discusses potential consequences for BLM resulting from the niche’s features.

This article argues that BLM attracts activists to join its cause from a diverse multimovement environment while simultaneously establishing a clear niche that differentiates it from other movements. This niche may be understood in terms of the identities, attitudes, and involvement of BLM activists. The claim that there is a clear niche does not imply that there is no overlap with other movements. Rather it implies that the characteristics of BLM activists are distinct enough that they constitute an identifiable group. These activists stand out from the crowd.

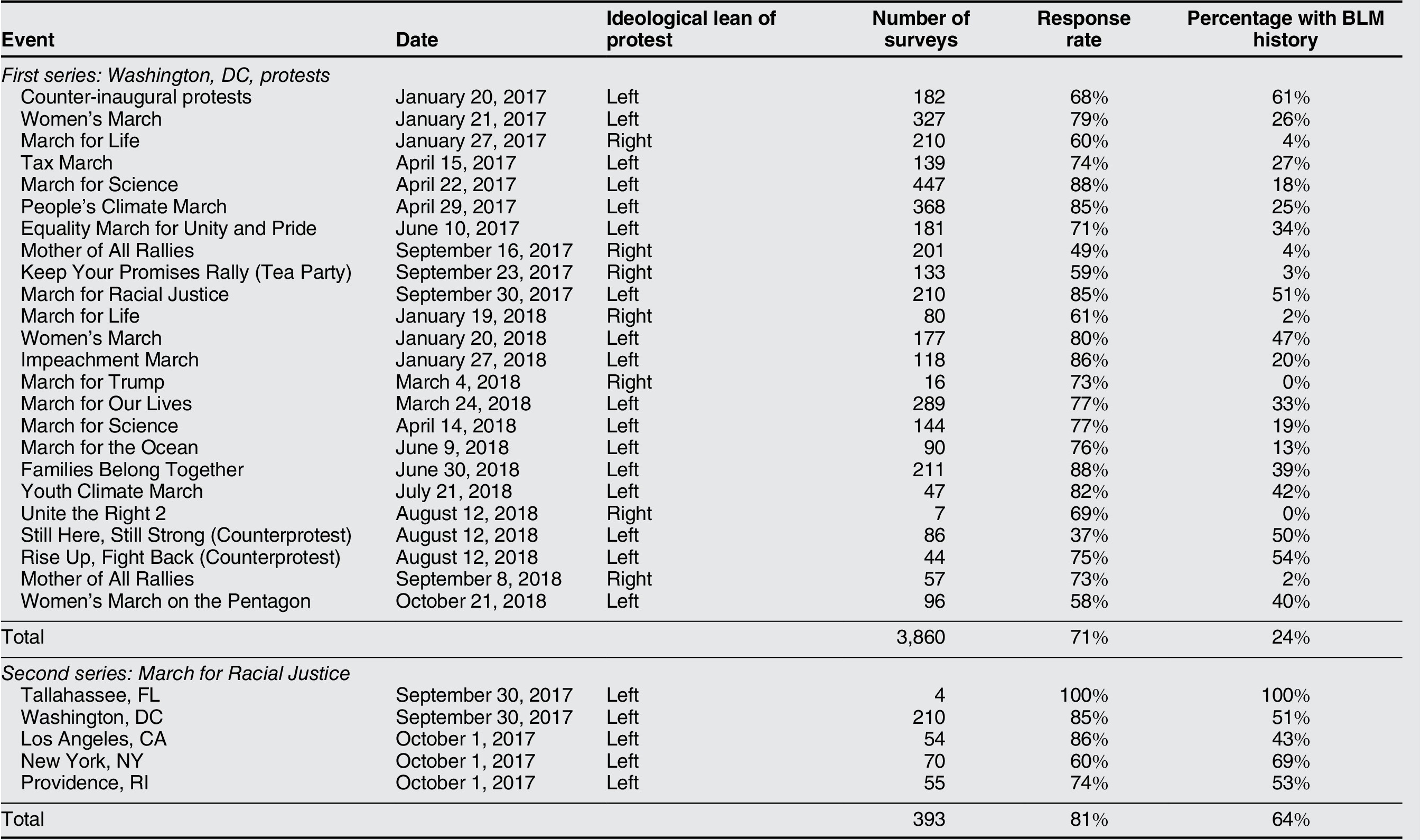

The evidence in this article is primarily based upon surveys of protest participants conducted at all (or almost all) nationally oriented demonstrations held in Washington, DC, during the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency (2017–18). A total of 3,860 surveys were collected from randomly selected participants at 24 events, with 937 of these respondents (about 24%) reporting involvement in BLM. The majority (17) of these events were left leaning due to the prevailing grassroots opposition to the Trump administration, though there were some (seven) right-leaning events included in the study. In order to create a comparison with nationally focused events, 393 surveys were conducted in five cities during the March for Racial Justice (September 30 and October 1, 2017), a series of events allied with BLM, with 253 respondents (approximately 64%) indicating involvement with BLM. This research design allows us to view BLM within a broad range of movements active at the national level, as well as with respect to racial justice activists outside the nation’s capital.

The survey data show that BLM often draws heavily upon allied progressive activism, especially other Black identity or civil rights causes and peace-antiwar movements. In comparison with typical activists in other social movements, BLM activists tend to lean further left–liberal ideologically but are not as strongly identified with political parties, are more likely to join political organizations, identify strongly as activists, and have closer ties with other activists.

With respect to attitudes and involvement, the study finds that BLM activists have a greater-than-average commitment to intersectional activism than do comparable activists in other movements, and use social media more regularly for political purposes. BLM activists tend to be less satisfied with how democracy is practiced in the United States and more likely to acknowledge justifications for using violence for political purposes than do their peers working on other causes. Activists who have participated in BLM are more likely than those in other movements to report having experienced especially high levels of anger in conjunction with politics. The evidence suggests that BLM is not especially prone to cleavages based on geography, allyship status, or activist background.

The article begins by discussing activists’ niches and their importance to the study of social movements. Second, a series of hypotheses is developed based on prior scholarship on social movements, Black politics, and the BLM movement, as well as visions of the movement articulated by its leaders. Third, a detailed explanation is given for the study’s procedures and data. Then the article proceeds with a series of analyses on activists’ backgrounds, demographics, identities, attitudes, and involvement, followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. The article concludes by highlighting what it reveals about the vital role of BLM in American democracy, particularly the potentially profound effects of BLM’s niche in politics that is intersectional, decentralized, and anti-institutional. It proposes future research on the niches of BLM and other social movements.

This study makes several significant scholarly contributions. First, it provides insight into the nature of a movement’s niche in a national political environment with many other contending social movements. While casual observers may be inclined to think of movements as independent and separate from one another, in fact they are closely connected (Heaney and Rojas Reference Heaney and Rojas2014; McAdam Reference McAdam and Traugott1995; Minkoff Reference Minkoff1997). The nature of contemporary mobilization makes it impossible for leaders to determine who can or cannot participate in a movement, but that does not mean that a movement cannot craft a recognizable following. Second, the survey results provide a more intricate description of BLM activists, beyond the extant knowledge that they tend to be disproportionately identified as racial or ethnic minorities, young, and lower income (Baskin-Sommers et al. Reference Baskin-Sommers, Simmons, Conley, Chang, Estrada, Collins and Pelham2021; Fisher Reference Fisher2019; Hope, Keels, and Durkee Reference Hope, Keels and Durkee2016). They have an ideological, partisan, and organizational profile that stands out from other movements. The nature of this profile is relevant to the place of BLM in American democracy, notably as a touchstone for political conflict and as an example to other movements. Third, the study provides a comprehensive view of BLM activists prior to the murder of George Floyd. Thus, it affords a baseline of comparison for recent research that has been especially attentive to the post-Floyd period (Acheme and Cionea Reference Acheme and Cionea2022; Baskin-Sommers et al. Reference Baskin-Sommers, Simmons, Conley, Chang, Estrada, Collins and Pelham2021; Cobbina et al. Reference Cobbina, LaCourse, Brooke and Chauduri2021; Gause and Arora Reference Gause and Arora2021).

The Meaning and Relevance of a Movement’s Niche

The concept of a niche is derived from biology but has been widely applied in the social sciences (see, inter alia, Aldrich Reference Aldrich1979; Hannan and Freeman Reference Hannan and Freeman1977; McPherson Reference McPherson1983). At the most basic level, a niche consists of a vector of characteristics (c1, c2, …, ck) that define the precise location of an entity in k-dimensional space. Niches may be distinct from one another or niches may overlap to some degree. Scholars have examined how social movements and their affiliated organizations create niches by sharing membership characteristics such as age, social status, use of protest tactics, issues, administrative capacity, and organizational missions (Levitsky Reference Levitsky2007; Olzak and Johnson Reference Olzak and Johnson2019; Stern Reference Stern1999). For example, two movements that draw on supporters from different age ranges may be thought of as having distinct niches. Whereas, organizations with supporters of similar ages may be thought of as having overlapping niches. Of course, niches need not only be defined on the basis of age but can be derived from other supporter characteristics that may be important to the movements.

Social movements in contemporary politics face challenges from overlapping niches because of the increasingly crowded nature of political environments (Browne Reference Browne1990). New movements are especially constrained by the fact that potential supporters have prior commitments to causes that they may have advocated for many years. A new movement thus crafts a niche either by drawing fresh participants to the political scene and/or by convincing established actors to redirect their energies toward the emerging cause.

Prior research on niches has been particularly concerned with the way that the degree of overlap among niches affects competition among social movements and social movement organizations (McPherson Reference McPherson1983). This overlap may change over time in ways that are consequential to a movement’s success (Stern Reference Stern1999). Olzak and Johnson (Reference Olzak and Johnson2019) demonstrate that when movement organizations share issue niches with other organizations, the resulting competition increases the likelihood that movement organizations will disband.

The sociologist Sandra Levitsky (Reference Levitsky2007) departs from the conventional approach to studying movement niches by making the case that movement niches are not only relevant to competition over members but also to the establishment of a movement’s collective identity. She argues that the emergence of niches helps to establish a sense of “we-ness” in a movement. In Levitsky’s account, the formation of niches aids actors in a movement in realizing and appreciating their place in the work of the movement. Importantly, Levitsky’s approach reveals how social movement actors reflect on the nature of their niche in order to inform the understanding of the movement’s collective identity, which changes over time.

Verta Taylor and Nancy Whittier (Reference Taylor, Whittier, Morris and Mueller1992, 105) explain that “collective identity is the shared definition of a group that derives from members’ common interests, experiences, and solidarity.” Some scholars of Black politics may be inclined to think of collective identity as akin to the notion of linked fate (Dawson Reference Dawson1994), but the two concepts are distinct. If activists have a sense of linked fate, that may indeed motivate them to hold a collective identity. But there are many other reasons for holding a collective identity that are unrelated to linked fate. These may include “action and interaction” among the participants in a movement (Fominaya Reference Fominaya, Snow, Soule, Kriesi and McCammon2018, 431), efforts by opponents to define a movement (Einwohner Reference Einwohner2002), and the endeavors of a movement’s leaders to project an image of worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment (Tilly Reference Tilly1993), sometimes referred to as “WUNC” or “WUNCness.”

Levitsky’s argument implies that the relevance of understanding a movement’s niche is that it helps the movement to grasp its own collective identity. To be clear, a collective identity and a niche are not the same thing. A collective identity is an imagined sense of what a movement is (Polletta and Jasper Reference Polletta and Jasper2001). A niche is closer to a raw description of its members. Yet the two are related because who actually turns up for a movement’s work has the potential to check—or influence—what a movement imagines itself to be. For example, if a movement espouses a collective identity of being multiracial—but its participants realize a niche that is limited in racial diversity—it may be implausible to sustain that multiracial identity. A movement’s leaders may be compelled to adjust their vision of their collective identity once they observe their realized niche. Or, they may strive to alter their realized niche in order to align with their imagined identity.

Hypotheses for Niche Realization

This section develops hypotheses for the realization of a niche by the BLM movement. These hypotheses are based on prior scholarly research relevant to social movements and Black politics. They are also inspired by observations made of BLM itself by scholars and BLM leaders. Thus, the study mixes deductive and inductive approaches to formulating hypotheses.

The analysis begins with a focus on two factors that its leaders intended to be central to its collective identity: intersectionality and decentralization. Then the analysis moves to factors that may be less within leaders’ control or may be less flattering aspects of collective identity: democratic satisfaction, justification of political violence, and emotions.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is the theory that when people are trapped in multiple axes of oppression, the disadvantages they experience are distinct from those they would have experienced had they been subject to only one dimension of oppression. Consider race, sex, and class as three pervasive axes of oppression (hooks Reference hooks1984). A person in the United States who is Black, female, and poor is likely to suffer from the combined effect of these dimensions. For example, a poor Black woman may be likely to experience a different kind of stigma when seeking state financial assistance than if she were Black only, female only, or poor only (Hancock Reference Hancock2007). Of course, the axes of oppression may extend beyond race, sex, and class to include language, disability, immigration status, sexuality, region of birth, religion, or other dimensions of difference (Dhamoon Reference Dhamoon2011). While it is possible to imagine that intersectionality could emerge from the combination of any two axes of oppression (e.g., sexuality and religion), some scholars maintain that intersectionality must be rooted specifically in the experiences of Black women, who are responsible for originating the concept (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2012).

The term “intersectionality” was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989) in conjunction with her analysis of antidiscrimination policy in the United States. However, the core ideas of intersectionality can be traced to feminist writings more than one hundred years prior (Tormos Reference Tormos2017). While intersectionality may seem to some to be a good example of idiosyncratic academic terminology, in fact, active discussion of this concept takes place jointly between activist and academic circles; it is as much an activist idea as it is an academic theory. Commonly known as intersectional activism (and by numerous related labels), many activists and scholars advocate for an approach to activism that seeks to address intersectional oppression in society and within the ranks of social movements (Roberts and Jesudason Reference Roberts and Jesudason2013; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007; Terriquez Reference Terriquez2015).

A commitment to intersectional activism is a central tenet of the BLM movement. BLM was cofounded by Alicia Garza, Patrice Cullors, and Opal Tometi—three Black women—who have sought to emphasize intersectionality and preserve a prominent role for Black women in the movement (Clark, Dantzler, and Nickels Reference Clark, Dantzler and Nickels2018; Clayton Reference Clayton2018; Lebron Reference Lebron2017, 67–96). This commitment has been embodied well by campaigns such as #SayHerName (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ray, Summers and Fraistat2017). If BLM is able to convey an intersectional message effectively to its supporters, then this idea is likely to be widely discussed in movement circles and internalized by participants (Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020). Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists are more likely to prioritize intersectional activism than are typical activists in other movements.

This hypothesis does not imply that other movements are not attentive to concerns about intersectionality. The Women’s March, for example, has been keen to stress the importance of intersectionality to its agenda and has mobilized activists who endorsed this view (Fisher, Dow, and Ray Reference Fisher, Dow and Ray2017; Heaney Reference Heaney2021). Rather, the hypothesis implies that support for intersectional activism is an unusually common view among BLM activists. As a consequence, it helps to make BLM activists distinctive within the broader activist community.

Decentralization

Activists and scholars have long debated about the best way to organize and lead social movements. In the public mind, individual leaders are often remembered as heroes who wrought social change. Names such as Susan B. Anthony (woman suffrage), Harriet Tubman (antislavery), Mahatma Gandhi (Indian independence), Martin Luther King, Jr. (civil rights), and Cesar Chavez (farmworkers) readily come to mind (Ganz Reference Ganz2009). However, some scholars have argued that leadership in social movements is more decentralized than it is often assumed to be (Morris and Staggenborg Reference Morris, Staggenborg, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004). Likewise, many activists have heralded the promise of decentralized movements to bring social change, with the Arab Spring sometimes cited as an exemplar of success (Howard and Hussain Reference Howard and Hussain2013). In the United States, the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011–12 was a highly visible experiment with extreme decentralization, though it was criticized by many for failing to convey a clear message that could facilitate policy change (Gitlin Reference Gitlin2012).

The founders of BLM took a strong position on this issue, asserting that BLM should emphasize decentralization. Rather than having central leaders, they describe BLM as a “leaderful” (not “leaderless”) movement; many people play the role of leaders at the grassroots (Cohen and Jackson Reference Cohen and Jackson2016). They claim to have taken this tack, in part, in response to criticisms of the civil rights movement as having been too centralized (Nummi, Jennings, and Feagin Reference Nummi, Jennings and Feagin2019). The movement has effected decentralization, in part, by building organizations as loose confederations of functional groups, each focusing on different tasks, such as elections, cultural work, and philanthropy (Woodly Reference Woodly2022, 150). Local BLM groups amplify decentralization by relying heavily on social media to organize events; in some cities, daily attention to Instagram may be necessary to follow upcoming actions (Heaney Reference Heaney2020). Online spaces too have become sites for BLM supporters to gather around topics such as #TrayvonMartin, #FergusonIsEverywhere, #ICantBreathe, and #TamirRice (Jackson, Bailey, and Foucault Welles Reference Jackson, Bailey and Welles2020). As a result, decentralization through social media has become an integral part of the movement’s collective identity (Ray et al. Reference Ray, Brown, Fraistat and Summers2017).

As there is a close association between social media and decentralization, it is possible to think about reliance on social media by grassroots activists as decentralized participation in the movement. Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists are more likely to use social media on a regular basis than are typical activists in other movements. Of course, this hypothesis is not suggesting that other movements are not decentralized or that their activists do not use social media. Rather, it proposes that BLM activists use social media tools more than is typical, making high decentralization a viable approach for the movement. These features help to mark the way that participation in the movement regularly takes place.

Democratic Satisfaction

The BLM movement focuses on issues that expose deep problems in the American political system and society. Continuing police violence against Black people reminds observers that American democracy does not serve these communities well (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek Reference Jefferson, Neuner and Pasek2021). Black communities have suffered long-standing marginalization and have consistently been denied their rightful protection by legal authorities and full participation in political institutions (Cohen Reference Cohen1999). This systemic racism is rooted in hundreds of years of slavery, segregation, and discrimination (Feagin Reference Feagin2006).

To examine these kinds of concerns about institutional structures and performance, political scientists have traditionally examined levels of diffuse support for the political system (Easton Reference Easton1975). They are usually operationalized as measures of democratic satisfaction (Linde and Ekman Reference Linde and Ekman2003). When activists are dissatisfied with the basic functioning of the democratic system, they may be prone to turn to protests that call for broad changes in the way that political institutions work (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2019, 44; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, 218). As Jennifer Oser and Marc Hooghe (Reference Oser and Hooghe2018) have documented, citizens are often inclined to turn toward noninstitutionalized participation, such as protest, especially when the denial of social rights is threatened.

The pervasive nature of systemic racism in the United States means that democratic satisfaction should be markedly low among people participating in BLM events. Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists are likely to express lower levels of satisfaction with the way that democracy works in the United States than are typical activists in other movements. As the relevant comparison group is other activists, the expectation is not that non-BLM activists are exactly thrilled with the way American politics works. Instead, it is that BLM activists, on average, are likely to object more fundamentally to the American political system. This expectation is in line with a long tradition of Black political thought that leans on radical rather than liberal approaches to confronting systemic problems (Dawson Reference Dawson2001).

Political Violence

Political philosophers have argued stridently that there can be no true moral justification for political violence (Frazer and Hutchings Reference Frazer and Hutchings2019). At the same time, people regularly turn to violence to advance their political ends. The United States was born of political violence during its war for independence against Great Britain. Politically motivated violence has continued throughout American history, with the January 6, 2021, attack on the United States Capitol by supporters of President Trump serving as a significant recent example. The Civil War of 1861–65 was the bloodiest case of political violence in the nation’s history, with violence both leading up to and following the war. Nathan Kalmoe (Reference Kalmoe2020) has documented extensively that Civil War violence was tethered to partisanship, which played a major role in motivating and justifying violence on the part of millions of people.

Ordinary people may access an array of justifications and motivations for turning to political violence. Given the complexity of the modern world, some people may see insurrections and riots as their only real hope for acting together to make a difference (Arendt Reference Arendt1969, 83; Ginges Reference Ginges2019). Support for violence is enhanced as the severity of grievances increases, as well as when opportunities to act efficaciously expand (Dyrstad and Hillesund Reference Dyrstad and Hillesund2020; Tilly Reference Tilly2003) or when state repression becomes heavier (White Reference White1989). People may see the need for violence in order to save their country or community from the enemies of democracy or otherwise evil people (Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2020). Political leaders may be instrumental in encouraging support for violence, especially when they articulate violent metaphors (Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2014). Likewise, participation in activism and encouragement from peer groups can lead people to take a violent posture (Becker Reference Becker2021; LaFree et al. Reference LaFree, Jensen, James and Safer-Lichtenstein2018).

In light of these findings from prior research, there are numerous reasons to expect that activists in BLM may be keen to offer justifications for political violence. Unabated violence by police against the Black community may be viewed as a form of repression and a violent response may seem to some to be the only way to get authorities to notice them and to respond. From this perspective, political violence may be essential for protecting the community from the state in what is regularly a matter of life or death. Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists are more likely to acknowledge justifications for political violence than are typical activists in other movements.

This hypothesis does not imply that every BLM activist is supportive of political violence. Activists may have good reasons to restrain themselves from endorsing violence, as there is extensive research indicating that political violence is more likely to backfire (by decreasing public support for the cause or its chances for success) than it is to advance a cause (Chenoweth and Stephan Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011; Feinberg, Willer, and Kovacheff Reference Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff2020; Wasow Reference Wasow2020). Further, the hypothesis is not meant to suggest that BLM activists are the only activists to justify violence, as there is a record of activists using violence for many causes, such as the antiabortion movement (Nice Reference Nice1988), the environmental movement (Beck Reference Beck2007), and the anti-Vietnam-War movement (Brick and Phelps Reference Brick and Phelps2015). Finally, it is necessary to clarify that this hypothesis is about activists being willing to see political violence as potentially justified; it is not about whether they have acted or plan to act violently.

Emotions

Emotions play an inextricable part in political life because they make people aware of the ways that events in the world affect their well-being and, thus, lead them to think differently about politics (Albertson and Gadarian Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015, 4). This awareness motivates people to take action (Brader Reference Brader2006, 50). Thus, it is not surprising that participants in activism tend to display stronger emotions than do ordinary people (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2019, 153). In turn, social movements depend heavily on emotions in order to attract participants, motivate them to act, and sustain their involvement. For example, movement leaders may select collective action frames with the goal of stoking people’s moral outrage about how government authorities are neglecting or mismanaging a social problem (Klandermans Reference Klandermans1997, 17).

Anger is an omnipresent emotion in politics. As a reflex emotion, it enables people to have a relatively quick response to events, creating a high potential for both regret and disruption (Jasper Reference Jasper2018, 4, 32). Because of its explosive capacity, social movement organizations usually aim to control the expression of anger. However, organizations may be able to benefit from their supporters’ anger if they can couple it with a clear sense of blame toward their political targets (Aytaç and Stokes Reference Aytaç and Stokes2019, 109).

Anger presents delicate issues for racial justice movements. As Davin Phoenix (Reference Phoenix2019) argues, Black citizens in the United States experience special risks when expressing anger publicly, so they may be advised to restrain their emotions. Despite this restraint, Black citizens are inclined to express anger on topics pertaining to race or the dysfunction of the overall political system (Phoenix Reference Phoenix2019, 66). Given that police killings of unarmed civilians are especially prone to generate anger, blame, and indignation, we can hypothesize that BLM activists are more likely to report feeling anger in conjunction with politics than are typical activists in other movements.

As is the case with the above hypotheses, this hypothesis is not meant to imply that activists in non-BLM movements do not experience anger. Anger is important to most social movements, with a case such as the Hare Krishna movement being the exception that proves the rule. Rather, it suggests that BLM focuses on events that are exceptionally likely to evoke anger, making it reasonable to expect that participating activists report high levels of anger. This anger is not necessarily due to the approach of BLM leaders, who may have incentives to keep anger at bay. Finally, it is relevant to note that this hypothesis (as well as the above hypotheses) pertains not only to Black participants in BLM, but to all BLM participants, who may be of any race or ethnicity.

Research Design

The primary data source for this article is a series of pen-and-paper field surveys collected at nationally advertised weekend protest events held in Washington, DC, in 2017 and 2018, which had an overall response rate of 71%. The goal of the research was to conduct surveys at all of the key protest events held in the nation’s capital during what was an extraordinary time of grassroots resistance (Meyer and Tarrow Reference Meyer and Tarrow2018). This approach does not yield a representative sample of all activists nationwide, only of those who came to protest in Washington. Still, this population of activists is important because of the symbolic significance of DC for the nation’s politics and as a traditional center for protest.

Events were identified by following mass media, social media, activist email listservs, and personal networking with prominent activists. It would be foolish to claim that all events were in fact the subject of surveys, as it is always possible that something was missed. However, extensive media searches did not detect additional major events, making it reasonable to claim that the research design at least included almost all of the targeted events. A list of surveyed events is provided in table 1.

Table 1 Events Included in the Study

Note: The March for Racial Justice in Washington, DC, on September 30, 2017, appears in both the first and the second series of protests.

The sample encompasses highly publicized events, such as the Women’s March and the March for Our Lives, as well as lesser-known events, such as the March for Trump and the March for Racial Justice (MFRJ). Three events had a specific racial justice agenda (MFRJ; Still Here, Still Strong; and Rise Up, Fight Back).

A supplemental series of surveys was conducted in 2017 at MFRJ-coordinated events in Washington, DC; Providence, Rhode Island; New York; Tallahassee; and Los Angeles. Surveys in these cities reflected geographic diversity to the greatest degree that was possible under the constraints of limited advanced information on where events would be held, as well as finite financial resources for administering surveys. MFRJ was not a BLM-affiliated event, strictly speaking. Nonetheless, it shared many of the goals of BLM, such as ending police violence and systemic racism. The overall response rate for these surveys was 81%. This series of surveys was aimed principally at the goal of reflecting the geographic diversity of the movement. It also provides insight into how well the first series of surveys represents activists located outside DC.

At each event, surveyors began by surrounding the perimeter of the crowd. They were instructed to look into the crowd, select an anchor for the purpose of counting, and then to invite participation by the fifth person to the right of the anchor. If the person declined to participate, then the surveyor was instructed make a tally of their nonresponse, thus allowing the response rate to be calculated as the number of respondents divided by all persons invited to participate (i.e., respondents plus nonrespondents). Surveyors were instructed to continue inviting every fifth person until three surveys were accepted, after which a new anchor was selected and the counting process repeated. Respondents were asked to self-administer the anonymous, six-page paper survey using a pen and clipboard. Surveyors occasionally administered surveys verbally for respondents with visual impairments. The survey questions that were used in this article are reported in the appendix.

This sample-selection approach adopted in this study has been used in numerous empirical studies over the past two decades (see, inter alia, Fisher Reference Fisher2019; Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Stanley, Berman and Neff2005; Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2019; Goss Reference Goss2006; Heaney Reference Heaney2018; Heaney and Rojas Reference Heaney and Rojas2014; Walgrave and Rucht Reference Walgrave and Rucht2010). A review of this literature and a detailed discussion of this methodology is contained in Fisher et al. (Reference Fisher, Andrews, Caren, Chenoweth, Heaney, Tommy Leung and Pressman2019). Prior research has shown that these types of field approximations of random samples can produce reliable measurements within protest crowds by enforcing the sampling of random participants and not only “approachable peers” (Walgrave and Verhulst Reference Walgrave and Verhulst2011; Walgrave, Wouters, and Ketelaars Reference Walgrave, Wouters and Ketelaars2016; Yuen et al. Reference Yuen, Tang, Francis and Cheng2022).

Additional validation is provided by a recent comparative analysis conducted by Barrie and Frey (Reference Barrie and Frey2021). They examined publicly available data from surveys of the 2017 Women’s March participants independently conducted by Fisher (Reference Fisher2019) and Heaney (Reference Heaney2018), which used similar (but not identical) sampling methods. Barrie and Frey (Reference Barrie and Frey2021, 12–13) found that the Fisher and Heaney surveys matched one another within two percentage points with respect to measures of gender, age, and ideology, despite their separate administration. Further, Barrie and Frey found that data mined from tweets at the march yielded results that correlated highly with the Fisher and Heaney findings. This analysis provides strong evidence of the reliability and validity of this sampling approach.

Results

Activists’ Backgrounds

Given that BLM first surfaced as a clearly autonomous movement in 2013, the question arises as to where its activists came from. Were they new to grassroots politics? Or did they have relevant prior experience? Appreciating their backgrounds aids in making sense of BLM’s niche. To this end, the survey asked respondents to identify the issue of the first protest that they ever participated in and the approximate year it took place. Only 3.4% of respondents identified BLM as the topic of their first rally. Even for people who would eventually be a part of BLM, only 15.0% of these started their activism at a BLM event. These simple, descriptive findings are important in establishing a key fact for BLM: the vast majority of its activists started their activism in some other movement. An ongoing challenge for BLM, then, is to attract experienced activists to its cause while maintaining a recognizable niche.

The movement origins of BLM activists are documented in figure 1. A category is created for each type of movement that had at least one hundred respondents in the surveys. These were Black Identity/Civil Rights (112 respondents), Peace/Antiwar (503 respondents), Environment (155 respondents), Women’s Rights/Pro-Choice (448 respondents), and Conservative/Pro-Life (296 respondents). There were small groups of activists from a variety of other movements, such as Labor, Occupy Wall Street, Global Justice, LGBTQIA+, and Pro-Immigration. These were combined into a residual category of Other Progressive (553 respondents).

Figure 1 Probability of Transition to Black Lives Matter by Issue of First Protest

Note: survey means are weighted based on survey nonresponse differences by race and sex. These adjustments change probability values by less than 1%. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Movement origins are ordered in figure 1 based on the probability that a person starting with a protest on that issue would transition to BLM by the time they took the survey. As might be expected, people whose first protest was related to Black identity or civil rights were most likely to transition to BLM, with 44.2% of these activists doing so, significantly more than activists in most other progressive movements (with the exception of peace-antiwar movements). Conservative and pro-life activists were least likely to transition to BLM, with only 5.9% doing so.

The results in figure 1 shed light on which movements prove to be more reliable or less reliable allies to BLM. The data reflect the obvious natural transition from Black identity and civil rights concerns to BLM. Perhaps less obvious is that peace and antiwar activists were BLM’s second strongest allies, with 36.4% of these activists making a transition to BLM. Peace and antiwar activists were significantly more likely to join BLM than were women’s rights and pro-choice activists, which was the progressive movement least likely to make the transition to BLM. This finding presents some tension with prior research claiming strong intersectional commitments by Women’s March activists (Fisher, Dow, and Ray Reference Fisher, Dow and Ray2017; Heaney Reference Heaney2021).

Demographics and Identities

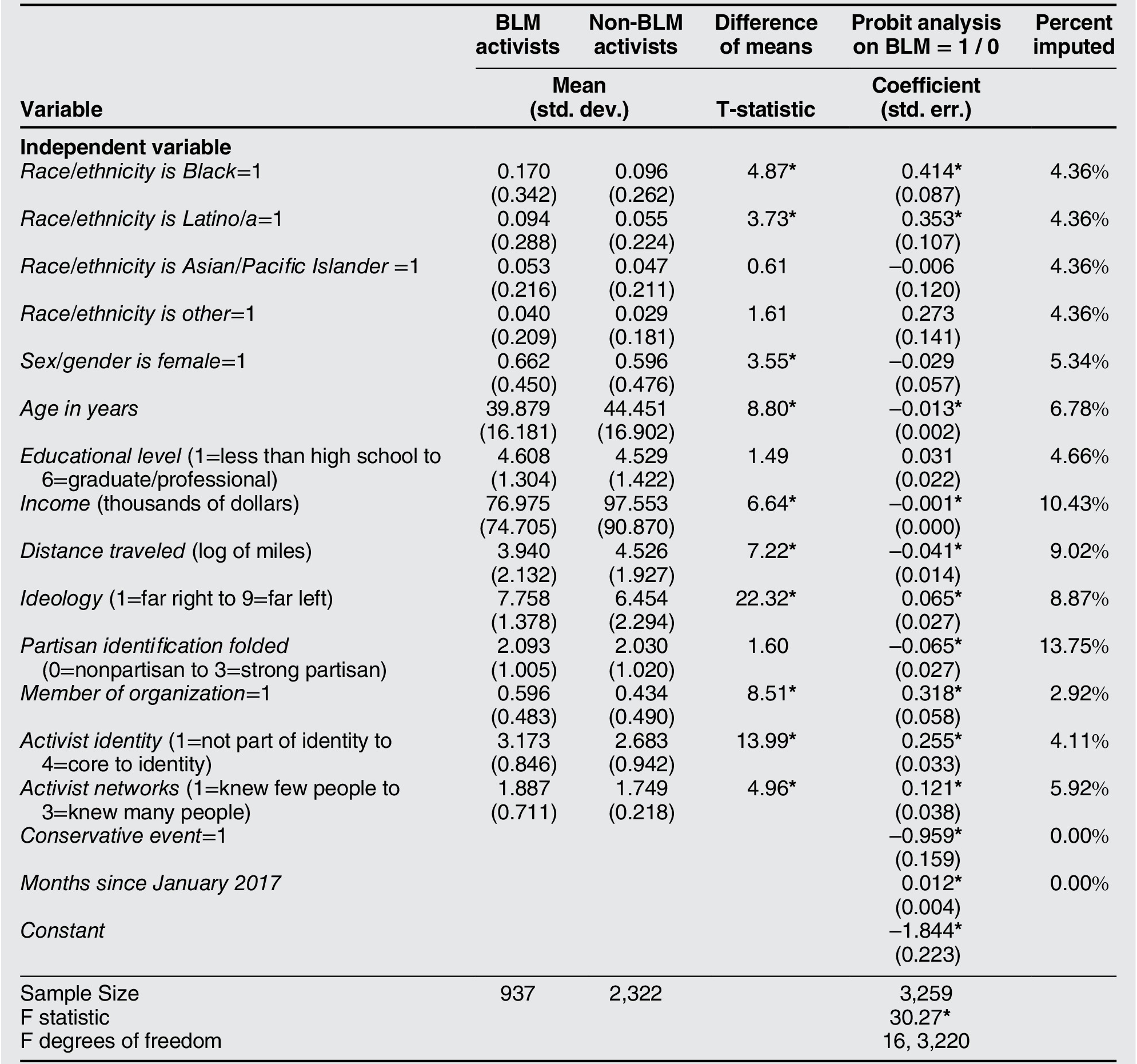

Before testing the five hypotheses stated above, this section compares BLM activists with those in other movements based on their demographics and identities. The variables examined in this section serve as control variables in the hypothesis-focused results reported in the next section.

Demographic comparisons are made on the basis of race/ethnicity, sex/gender, age, education level, and distanced traveled to DC. Identity comparisons include ideology, partisan identification, organizational membership, activist identity, and activist networks. First, simple bivariate comparisons are made between BLM and non-BLM activists. Second, multivariate comparisons are made between these same activists using a probit estimator in order to assess if differences are statistically significant, while holding other variables constant. For example, are gender differences significant after accounting for race? Characteristics of events where respondents were observed are included in this analysis, accounting for whether the respondent was observed at a conservative event and when the event took place in the protest cycle (i.e., months since Trump’s inauguration).

The analysis described here is based on standard errors that are clustered by event and surveys that are weighted based on nonresponse according to race/ethnicity and sex/gender. Missing values are imputed using complete-case imputation, which is an appropriate method when missingness is minimal, as is the case in this study (King et al. Reference King, Honaker, Joseph and Scheve2001; Little Reference Little1988).

Differences between BLM and non-BLM activists are reported in table 2. Considering first the simple comparison of BLM activists with non-BLM activists, 10 of the 14 variables examined have statistically significant differences between the groups. With respect to demographics, BLM activists are more likely than non-BLM activists to self-identify as Black or Latino/a, but there are no significant differences for activists self-identified as Asian or Other. BLM activists are significantly more likely to self-identify as female and report being about five years younger, on average, than the comparison group. The education levels reported by BLM activists are not significantly different from those of non-BLM activists. Both groups, on average, have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is greater than the average educational attainment of adults in the general population, only 32% of whom have reached this level (US Census Bureau 2019). BLM activists earn about $20,000 per year less on average than do non-BLM activists, which is a statistically significant difference. Non-BLM activists travel significantly greater distances to attend protests in DC than do BLM activists; about 40 miles farther, on average. Thus, BLM activists are significantly more likely to be residents of Washington, DC, or to live close to it.

Table 2 Demographics and Identities by Participation in Black Lives Matter

Note: *p ≤ 0.05. Missing values were imputed using complete-case imputation. Survey weights were applied to account for differences in nonresponse based on race/ethnicity and sex/gender. Standard errors were clustered by event when estimating significance levels.

With respect to identities, BLM activists identify significantly further to the left on the ideological spectrum than is the case for non-BLM activists. They are also significantly more likely to identify as a member of a political organization and as an activist. They report significantly closer networks with other activists, as indicated by their self-perception of the number of people they know at the event they were surveyed at.

The multivariate probit analysis suggests the need for two corrections to the bivariate analysis. First, sex/gender is not significant in the probit equation reported in table 2. This implies that differences in sex/gender from the bivariate analysis may be accounted for with other variables in the analysis. Second, partisan identification emerges as significant in the multivariate analysis (see also Drakulich and Denver Reference Drakulich and Denver2022), while it was not significant in the bivariate analysis. This result indicates that BLM activists’ partisan attachments are clearer once control variables are incorporated into the model. Other than that, there were no significant differences between the two approaches. The probit model includes a parameter for whether respondents were observed at conservative events, indicating that people surveyed at these events were significantly less likely to support BLM. It also includes a variable for the number of months since Trump’s inauguration. The significant positive coefficient on this variable shows that BLM activists were more likely to be at later events, suggesting that the movement grew over the period of the study.

As a robustness check (reported in online appendix A), the probit model was reestimated without survey weights or clustered standard errors. These results are nearly identical to those reported in table 2, with the only notable exception being the presence of a statistically significant coefficient on the Other race/ethnicity variable in the robustness check.

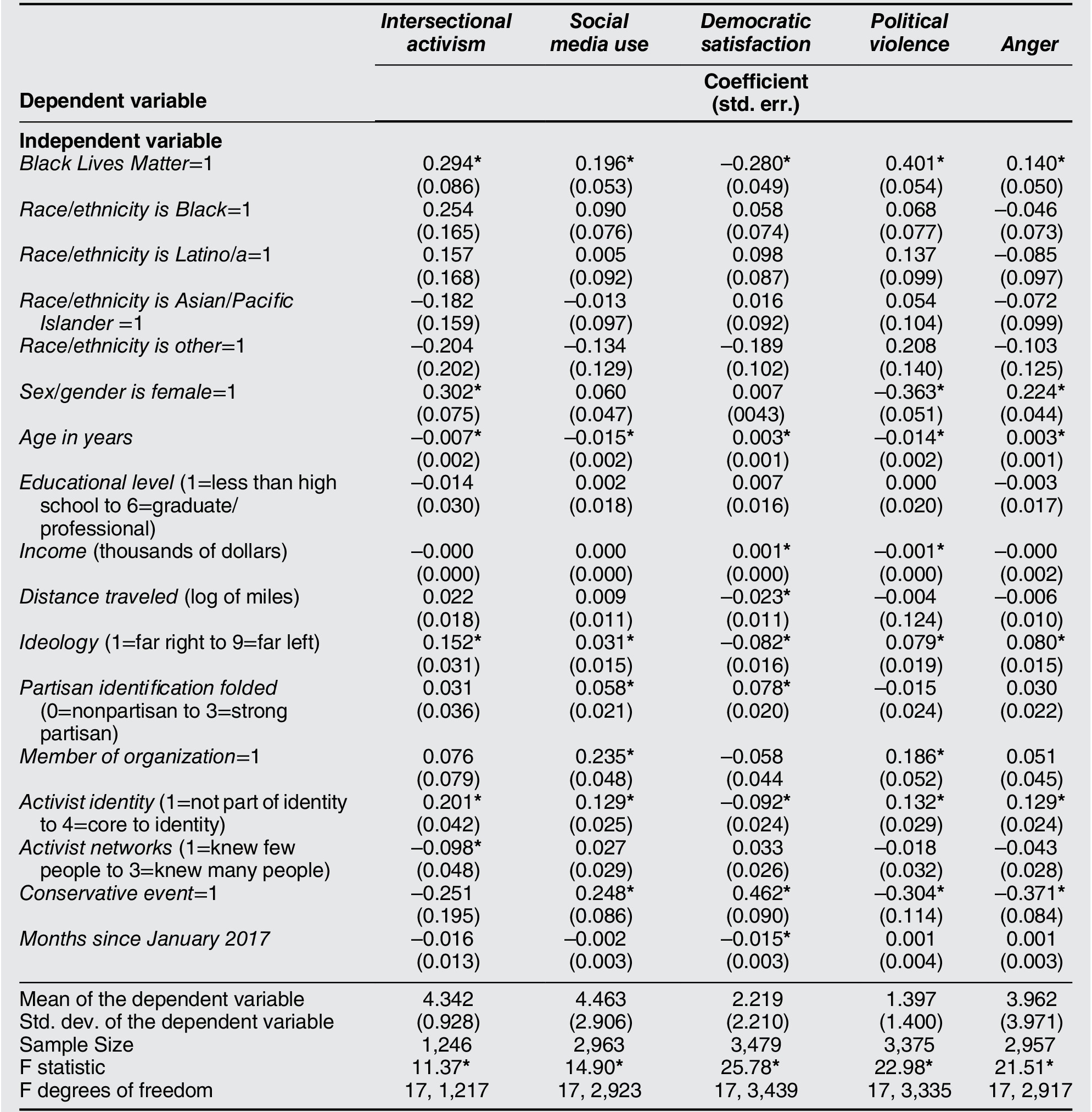

Attitudes and Involvement

The previous section describes the differences between people who reported showing up for BLM events and those who did not. Now the analysis turns to the hypothesized variations in activists’ attitudes and political involvement, holding the previously considered demographic and identity variables constant. Table 3 contains five equations, one for each of the five main hypotheses. Each equation was estimated using an ordered probit model. As was the case for the equations in table 2, the standard errors were clustered by event and weighted for nonresponse differences, with missing values estimated using complete-case imputation. Note that these models contain the same independent variables as in table 2, though these variables are only used for statistical control and are not interpreted. The coefficients on past BLM rally attendance are the focus of the hypothesis tests.

Table 3 Differences in Attitudes and Political Involvement among Washington, DC, Protesters

Note: *p ≤ 0.05. Coefficients were generated using an ordered probit estimator. Missing values of the independent variables were estimated using complete-case imputation. Surveys were weighted according to nonresponse based on race and sex. Standard errors were clustered based on event.

The results reported in table 3 indicate that BLM activists are significantly different from non-BLM activists in each of the five hypothesis tests. First, BLM activists are significantly more inclined to agree that social movements should practice intersectional activism than are activists not in BLM. As the marginals graph in figure 2a shows, this result was associated with BLM activists being more willing to say that intersectionality should be “equal to the highest priority” of the movement than are non-BLM activists. Thus, the evidence supports the view that BLM activists typically have deeper commitments to intersectional activism than does the average activist that is not involved in BLM, after accounting for key demographics, political affiliations, and event characteristics. It is important to note that the intersectionality survey question was only asked in 2018, meaning that only 1,246 valid observations were used for this analysis.

Figure 2 Marginal Graphs for Black Lives Matter Participation Regarding Attitudes and Political Involvement

Second, BLM activists claimed more frequent politics-related social media use than did non-BLM activists, controlling for other determinants of social media use. The marginals graph displayed in figure 2b places the differences between groups at the ends of the spectrum. BLM activists were more likely to say that they used social media seven days per week and less likely to say that they used it zero days per week. Yet the two groups are statistically indistinguishable in their inclination to use social media one to six days per week.

Third, BLM activists were significantly less likely to admit that they were satisfied with the way that democracy works in the United States than were non-BLM activists. Figure 2c reveals that neither set of activists differs much in their propensity to answer “very satisfied” (the highest option). However, BLM activists were significantly less likely to say that they were “fairly satisfied” (the second-highest option). Both groups are about equally likely to report that they are “not very satisfied” (the next-to-lowest option). But BLM activists are significantly more inclined to say that they were “not satisfied at all” (the lowest option). This evidence establishes that BLM activists were much more likely to hold especially critical views on how American democracy works (or does not work), after controlling for other key factors.

Fourth, BLM activists are more likely to see at least some justification for political violence than are activists who are not in BLM. It must be observed at the outset that the overwhelming majority of all activists held that there was never any justification for political violence. Still, there are marginal but statistically significant differences between BLM and non-BLM activists. As figure 2d indicates, the marginal propensity of non-BLM activists to answer that political violence is not at all justified was almost 80%, other things equal. However, the marginal propensity to agree with this view was only about 65% among BLM activists. The marginal propensity for BLM activists to find “a little” justification for political violence was approximately 20%, while it was closer to 15% for non-BLM activists. Likewise, the marginal inclination of non-BLM activists to believe that violence is justified “a moderate amount” was close to 5%, other things equal, while the inclination was closer to 10% among BLM activists. Both groups solidly rejected the position that political violence could be justified “a lot” or “a great deal.”

Fifth, BLM activists said that they had more intense emotions associated with politics than did non-BLM activists. Table 3 shows that BLM activists reported higher levels of anger, other things equal. Examination of figure 2e suggests that BLM activists are slightly more likely than non-BLM activists to feel anger “almost always” when thinking about politics, while they were slightly less likely to say that they felt it “often” or “sometimes.” These individual marginals may not be statistically significant, but the marginals combine to create a statistically significant result overall. Neither group had many respondents claiming that they felt anger “rarely” or “never.” Some feelings of anger with respect to politics were nearly universal among the respondents to these surveys of activists.

The distinctiveness of BLM activists can also be illustrated by considering BLM in comparison with four other movements: the women’s movement, climate movement, antiwar movement, and the Tea Party. Figure 3a–f is composed of predictions on each of the five dependent variables when all other variables are at their mean values. The bars in these figures represent 95% confidence intervals of the estimates. Figures 3a through 3e make it plain that BLM stands out from these comparison movements on all five dimensions. Figure 3f was constructed using multidimensional scaling on the sum of the distances between movements (with each dependent variable weighted equally), with the circles representing 95% confidence intervals around the point estimates. This graph shows that BLM and the Tea Party are separate from the pack with clear niches, while the women’s movement, climate movement, and antiwar movement overlap substantially with respect to their supporters.

Figure 3 Movement Niches Compared

As a robustness check, the analyses reported in table 3 were reestimated without sample weights or clustered standard errors. Additionally, the models were reestimated without the control variables to make sure that the significant coefficients on the BLM variables are not an artifact of the control variables. These results are reported in online appendix B. They reveal no significant differences in the BLM coefficients or the patterns in the marginals graphs as a result of these varied specifications.

Movement Cleavages?

The results presented in this article suggest the presence of a clear niche for BLM, as indicated by significant differences on a series of variables in comparison with activists in other movements. However, one factor that could undercut the clarity of the movement’s niche would be pervasive divisions within BLM. To investigate this possibility, three possible cleavages in the movement are considered: geography, allyship status, and activist background. Hypotheses regarding each of these issues are tested only for activists who reported participating in BLM.

A first possible cleavage is geographic differences in the movement, as the same movement may assume differing configurations depending on the location of the activism (Miller Reference Miller2000). Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists in Washington, DC, differ from BLM activists in other cities. The results of the analysis of data collected in five cities at the MFRJ are reported in table 4. Full models were estimated with all control variables, though only the focal coefficients are reported, to conserve space (with full results documented in online appendix C). They show that there are not significant differences between Washington, DC, and the other four cities with respect to three of the four dependent variables examined in table 3 (data on intersectional activism were not available for the MFRJ). The results do show that activists protesting in Washington, DC, have significantly higher satisfaction with the way that democracy works in the United States than is the case for activists protesting in other cities. This difference may be associated with the fact that many of these activists traveled to DC because they believed that this was a place where their voices would likely be heard. Considering the estimates of all four equations, the cleavage hypothesis is only somewhat supported in this analysis.

Table 4 Analysis of Potential Cleavages among Black Lives Matter Activists

Note: *p ≤ 0.05. † Data on intersectional activism were not available for the MFRJ. Coefficients were generated using an ordered probit estimator. Coefficients are only reported for the focus variable in each model. However, full models were estimated and are documented in the online appendixes. Missing values of the independent variables were estimated using complete-case imputation. Surveys were weighted according to nonresponse based on race and sex. Standard errors were clustered based on event.

A second possible cleavage is allyship status. Given that the movement focuses on Black interests, non-Black activists in the movement may be thought of as allies. An example of BLM allies and core activists working together is provided in figure 4, which depicts a multiracial crowd of activists responding to the racist Unite the Right 2 rally in 2018. Prior research has suggested that the views of a movement’s allies often differ from those of the movement’s core activists, and this can be distracting or unwelcome to activists in the movement (Brown and Ostrove Reference Brown and Ostrove2013; Eichstedt Reference Eichstedt2001; Lichterman Reference Lichterman1995). Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM allies differ from BLM’s core activists along the primary dimensions of its niche. As was the case for the first possible cleavage, results of this analysis are reported for the focus variable only in table 4, with the full results documented in online appendix D. These results do not show significant differences between allies and core activists. Thus, the cleavage hypothesis is not supported in this analysis.

Figure 4 Rise Up, Fight Back Antiracist Counterprotest in Washington, DC

Note: August 12, 2018. Photo by author.

A third possible cleavage is activist background. Early activism can have a considerable effect on a person’s lifetime activism (Corrigall-Brown Reference Corrigall-Brown2011). Thus, we can hypothesize that BLM activists who started out in BLM, civil rights, or other Black identity activism differ from those activists who started out in other issue areas. The abbreviated results reported in table 4 (with full results in online appendix E) do not support this cleavage hypothesis.

Overall, this analysis suggests that the BLM movement is not readily divided with respect to the five principal variables under consideration in this article, as higher democratic satisfaction among activists in Washington, DC, (compared with other cites) is the only significant cleavage. This evidence bolsters the argument that these five factors can be thought of as helping to define a clear niche for BLM.

Limitations

The analysis in this article is DC-centered, as it is weighted toward activists who live in or near DC. This selection was made because of the symbolism of DC and its prominence for protests. However, there are many activists who never come to DC. An effort was made to address this problem by examining participation in the MFRJ in five cities. While this analysis provides some insight into the nature of BLM outside DC, it is limited by the fact that it was conducted only in cities on the East and West coasts. More research is needed on the mobilization of BLM in the heartland of the United States and outside large urban areas.

The focus of this article is on BLM protesters. It asserts that protesters are an important group in BLM that is worthy of attention, as protest is a principal tactic used by the movement. At the same time, it would be a mistake to assume that BLM only consists of street protesters. Many activists undertake all (or most) of their involvement only in online spaces, for example (Jackson, Bailey, and Foucault Welles Reference Jackson, Bailey and Welles2020). Thus, the fact that this study comprised exclusively of protest participants is a limitation to be remedied by future research.

This article examines five key variables that reflect BLM’s niche. It also probes these variables for evidence of cleavages within the movement. However, there are many other variables that could be examined to help understand BLM’s niche and cleavages. For example, questions could be raised about strategies for changing public policy and whether they are better undertaken at the local, state, or national levels. Further research is needed on a wider range of BLM activists’ perspectives.

Finally, this article is limited to the 2017–18 period, which was during the Trump presidency but before the murder of George Floyd. It would be valuable to repeat this analysis (to the extent possible) using data gathered before Trump’s election and after Floyd’s death. Such research could reveal the dynamics of the movement as well as the effects of BLM on other movements.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this article makes the case that BLM has established a clear niche, despite drawing activists from a wide array of other movements. In critical respects, BLM’s niche has achieved the vision that its founders and leaders imagined. BLM created and sustained a movement that prioritizes intersectional activism and governs in an informal, decentralized fashion that relies heavily on social media. The findings of the research do not show significant internal divisions in these areas. In unifying behind intersectionality and decentralization, BLM has at least partly attained the goals of a Black identity movement steeped in local democracy and unshackled by misogyny that has long eluded Black freedom struggles on the left (Dawson Reference Dawson2013, 168–70).

BLM’s approach helps to keep the movement’s focus on police violence and gives ordinary people a meaningful say in the actions that its affiliated organizations take. It is remarkable that BLM has been able to do this, while many other social movements are distracted from long-term organizing by an internet-fueled milieu that prizes short-term mobilization (Han Reference Han2014). Over the last decade, BLM has thrived while its contemporaneous movements have quickly dissipated, such as Occupy Wall Street (economic inequality), the March for Our Lives (gun control), and the March for Science.

Beyond intersectional activism and decentralization, BLM’s realized niche may not have been formed as intentionally and may present challenges for BLM moving forward. BLM activists tend to be deeply suspicious of the way that democratic institutions function in the United States. While the long history of systemic racism gives BLM activists good reasons for these suspicions, the anti-institutional sentiment in the movement may pose challenges for reaching its goals. Outside pressure no doubt helps movements to advance their goals, but it is often used most effectively in conjunction with an inside strategy (Kollman Reference Kollman1998). BLM leaders would be well advised to consider whether this dimension of its realized niche is consistent with their visions for its collective identity.

BLM leaders might weigh two approaches to the anti-institutionalism prevalent among its rank-and-file activists. One approach would be to embrace the anti-institutionalism. This path would position BLM as a perpetual radical flank in the protection of Black lives (Haines Reference Haines1984). There is power in this posture. If BLM activists are always ready to mobilize and never willing to negotiate, then it presents an ongoing challenge to the status quo of race relations in America. But it also leaves an opening for other actors to enter the fray as the insiders. These ostensibly moderate actors may advance an agenda that does not align entirely with the BLM vision. Thus, a second approach for BLM would be to nurture a specialized cadre of its supporters to pursue reform from the inside. While this tack may yield results, it is also vulnerable to charges from BLM’s rank-and-file activists that these insiders are “sellouts.”

Another dimension of anti-institutionalism is nonpartisanship. BLM activists have weaker attachments to political parties than is typical—a result that obtains only after holding constant an array of control variables. However, no matter what model specification is adopted, BLM activists are not comparatively strong partisans. This relative detachment may be part of what has allowed BLM to continue mobilizing effectively through changing parties in government. Michael Heaney and Fabio Rojas (Reference Heaney and Rojas2015) have shown that the dominance of strong partisans in a movement may pose risks to the movement’s goals because their loyalties fluctuate with the electoral success of their allied party. From this perspective, the comparatively weak partisan attachments of BLM activists free the movement of that potential liability. Indeed, previous scholarship by Paul Frymer (Reference Frymer1999) and Michael Dawson (Reference Dawson2013) has argued forcefully that unreliable allies in the Democratic Party have historically posed thorny obstacles for Black identity movements. BLM’s realized niche may sidestep this problem, at least in part, by ignoring potential Democratic allies.

The greater-than-typical willingness of some BLM activists to acknowledge justifications for political violence is an uncomfortable facet of the movement’s niche. It is worth reiterating that the survey question on which this conclusion is based asked if respondents thought that violence could be justified, not whether they had engaged in or were planning violence. Still, some BLM protests have been connected with violent events, though never at the direction or encouragement of BLM leaders (Fernandez, Pérez-Peña, and Bromwich Reference Fernandez, Pérez-Peña and Bromwich2016; Mansoor Reference Mansoor2020). This violence has surfaced at the same time as far-right-led violence and threats of violence have become increasingly prevalent (New York Times Editorial Board 2022).

On the one hand, violence by or against BLM activists is not within the control of BLM leaders. When protests take place in a free and open society—especially one with vigorously protected rights to own and carry firearms—little can be done to stop people who are determined to commit acts of political violence. As a result, violence may be an inevitable component of BLM’s collective identity. On the other hand, rising political violence in the American polity gives BLM leaders a calling to advocate for peace within and beyond the movement. If BLM is associated with violence (rightly or wrongly), people will listen when BLM leaders speak out to stop violence.

The finding that BLM activists typically feel above-average levels of anger in conjunction with politics is also a sensitive finding for the movement. As Phoenix (Reference Phoenix2019) explains, Black citizens may be especially vulnerable to backlash when they are perceived as being angry. This is a point on which having non-Black allies in the movement may be helpful. As this research documents, non-Black allies in BLM do not report feeling statistically different levels of anger than do core Black activists. And while self-identification as Black is a strong predictor of BLM participation, it is also true that the majority of activists reporting BLM involvement in this study identified as non-Black (in fact, the majority identified as white). These findings align with analysis in the New York Times showing that the crowds protesting George Floyd’s murder in 2020 were overwhelmingly multiracial in nature, with large numbers of white people in attendance (Harmon and Tavernise Reference Harmon and Tavernise2020).

Under these conditions, anger may be compatible with BLM’s desired collective identity. Whites and other non-Black activists may provide symbolic cover for expressions of anger at BLM events. Such backing may allow BLM to use anger as a resource. If blame can be assigned to a particular target—such as a police officer, police department, city council, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or the president of the United States—then anger can be the impetus for the kind of moral outrage that allows a movement to mobilize and exert political influence.

Looking forward to potential future research, this study leaves open many questions about how the nature of its niche affects BLM’s politics. Does the clarity of its niche create a free space for movement discourse? Does this separation make it difficult for BLM to connect with potential allies? When and how, if at all, did BLM’s leaders attempt to recast BLM’s collective identity in response to its own realized niche? How did the niche change as support for BLM grew in 2020 and then receded in 2021? How did these dynamics compare with other social movements? Answering these questions would require moving beyond the cross-sectional approach employed in this article to a more explicitly dynamic research design.

BLM may serve as an exemplar for other racial and ethnic justice movements in the United States. It demonstrates that movements can thrive while promoting intersectional activism. They can work together effectively by adopting a leaderful approach that eschews central decision making and allows grassroots activists to help shape actions through social media. It suggests that noninstitutional preferences, support for political violence, and feelings of anger may be unavoidable in a movement, but they may also be managed. New movements, such as Stop Asian Hate (which surfaced in 2021) and Hmong Americans for Justice (founded in 2015), may be able to adapt the BLM model to the needs of their communities. This may be a viable strategy for such groups to achieve recognition when their needs are systematically ignored by public officials (Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011, 4).

American democracy needs BLM and more movements like it. This is not to say that BLM is perfect or that it cannot be improved. Rather, it is to recognize that BLM has created a democratic model of organizing that can be identified and sustained amid the noise that accompanies the internet age. It reveals a workable approach to representing identity groups in an era when the United States is increasingly becoming a multiracial democracy. Concomitantly, far-right organizing is ascendant and ever-more paranoid in its style, posing threats to the existence of a liberal political system (Parker and Bareto Reference Parker and Bareto2013). Through BLM, citizens of any race or ethnicity have opportunities to stand against racism and advocate for social justice. BLM is not a panacea, but it is an opening to help forge multiracial democracy in the streets and on the internet.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001281

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges helpful suggestions and assistance from Endre Borbáth, Chris Carman, Lisa Disch, Dana Fisher, Steve Garcia, Kristin Goss, Jennifer Hadden, Darren Halpin, Vince Hutchings, Swen Hutter, Lorien Jasny, Anna Kirkland, Ken Kollman, Philip Leifeld, Suzanne Luft, Dave McKeever, David Meyer, Rob Mickey, Michael Mrozinski, Chris Parker, Rick Price, Fabio Rojas, Dieter Rucht, Tom Scotto, Dara Strolovitch, Sid Tarrow, Mark Tranmer, Nick Valentino, and four anonymous reviewers. This research would have been impossible without support from many research assistants, surveyors, and anonymous survey respondents. Michael Mrozinski played an especially critical role in helping to manage the fieldwork for the project. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Contentious Interactions Workshop at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Germany, October 20–21, 2021. Funding for this research was provided by the National Institute for Civil Discourse, the University of Arizona Foundation, and the University of Michigan through the Institute for Research on Women and Gender (IRWG), the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP), the National Center for Institutional Diversity (NCID), and the Organizational Studies Program (OS).

Appendix: Survey Questions Used in the Statistical Analysis

-

1. Over the course of your entire lifetime, which policy-issue rallies have you attended? Please circle all that apply:

-

• Black Lives Matter;

-

• Pro-women’s rights;

-

• Stop climate change;

-

• Antiwar;

-

• Tea Party;

-

• [23 more options not listed here];

-

• Other;

-

• I have never attended any policy-issue rally.

-

-

2. Please describe the first policy-issue rally in which you ever participated and give the approximate year in which it took place. (Please write “none” if you have never participated in a policy-issue rally).

-

3. How important is it that [protest movements] center, represent, and empower the perspectives of members of disadvantaged groups within their ranks, such as women of color, LGBTQIA+ persons, and low-income persons? Please circle one:

-

• Equal to the highest priority for the movement;

-

• A high priority, but not the highest priority;

-

• A moderate priority;

-

• A low priority;

-

• Not a priority;

-

• Don’t know/No opinion.

-

-

4. On the whole, how satisfied are you with the way that democracy works in the United States?

-

• Very satisfied;

-

• Fairly satisfied;

-

• Not very satisfied;

-

• Not satisfied at all.

(From the American National Election Study.)

-

-

5. How much do you feel it is justified for people to use violence to pursue their political goals in this country?

-

• Not at all;

-

• A little;

-

• A moderate amount;

-

• A lot;

-

• A great deal.

(From the American National Election Study.)

-

-

6. These days, how often does politics make you feel angry? Please check one:

-

• Almost always;

-

• Often;

-

• Sometimes;

-

• Rarely;

-

• Never.

-

-

7. During a typical week, how many days do you use social media such as Twitter or Facebook to learn about politics?

-

• None;

-

• One day;

-

• Two days;

-

• Three days;

-

• Four days;

-

• Five days;

-

• Six days;

-

• Seven days.

(From the American National Election Study.)

-

-

8. What is your race/ethnicity? Please circle as many as apply:

-

• Native American/American Indian;

-

• White/Caucasian;

-

• Black/African American;

-

• Latino/Hispanic;

-

• Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander;

-

• Other.

-

-

9. What is your sex/gender?

-

10. How old are you?

-

11. Could you please tell us the highest level of formal education you have completed? Please circle only one:

-

• Less than high school diploma;

-

• High school diploma;

-

• Some college/associate’s degree or technical degree;

-

• College degree;

-

• Some graduate education;

-

• Graduate or professional degree.

-

-

12. Could you please tell us your level of annual income in [2016/2017]? Please circle only one:

-

• Less than $15,000;

-

• $15,001 to $25,000;

-

• $25,001 to $50,000;

-

• $50,001 to $75,000;

-

• $75,001 to $100,000;

-

• $100,001 to $125,000;

-

• $125,001 to $150,000;

-

• $150,000 to $350,000;

-

• More than $350,000.

-

-

13. What is the ZIP code of your primary residence? (If you don’t live in the US, please tell us in what city and country you live.)

-

14. Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as (please circle one):

-

• To the “left” of strong liberal;

-

• A strong liberal;

-

• A not-very-strong liberal;

-

• A moderate who leans liberal;

-

• A moderate;

-

• A moderate who leans conservative;

-

• A not-very-strong conservative;

-

• A strong conservative;

-

• To the “right” of strong conservative;

-

• Other (please specify).

-

-

15. Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a (please circle one):

-

• Strong Republican;

-

• Not-very-strong Republican;

-

• Independent who leans Republican;

-

• Independent;

-

• Independent who leans Democrat;

-

• Not-very-strong Democrat;

-

• Strong Democrat;

-

• Other (please specify).

-

-

16. Are you a member of any political organizations, social movement organizations, interest groups, or policy advocacy groups?

-

• Yes;

-

• No.

-

-

17. Some people think that being an “activist”—meaning someone who tries to improve the world by working on certain issues or causes—is a very important part of who they are, while other people do not think of themselves as activists. How important is being an “activist” to your personal identity? Please circle one:

-

• Core to my personal identity;

-

• Somewhat important to my personal identity;

-

• Not that important to my personal identity;

-

• Not a part of my personal identity;

-

• Don’t know.

-

-

18. Prior to coming to this rally this week, did you already personally know many people here, or are you largely meeting people for the first time? Please circle one:

-

• I knew many people here before arriving at this rally;

-

• I knew some people here, but only a few;

-

• I knew hardly anyone here before arriving at this rally.

-