Some display a marked degree of dullness or stupor; others sharpness and cunning more allied to the tricks of monkeys than the acts of reasonable men.Footnote 1

When John Campbell published his reminiscences of thirty years’ experience as a prison medical officer in 1884, his comments on the traits of prisoners, quoted here, encapsulated the change in attitude towards prisoners that dominated penal policy in the late nineteenth century. Prisoners, once perceived as redeemable, were now regarded as unreformable, incorrigible, and of poor mental and physical stock. From the late 1850s onwards, fuelled by accusations that prisons were not deterring repeat offenders and that crime was increasing and becoming more brutal, British and Irish legislatures and publics expressed increased disquiet about the effectiveness of their prison systems. The flagship convict prisons, Mountjoy and Pentonville, lost their ‘model status’, and their significance as emblems of rehabilitation diminished, while the aims of spiritual reformists were dismissed as naïve and ineffectual.Footnote 2 Prison policy shifted away from disciplinary regimes emphasising reform towards the rigorous enforcement of expressly punitive regimes, including the separate system of confinement. This involved all prison officers, but placed prison medical officers in a particularly challenging position. As they strove to recreate themselves as experts in prison medicine and to enhance their professional status, they were also implicated in imposing new and severe systems of discipline, which proved detrimental to the physical and mental health of many prisoners, and ‘debasing to the mental faculties’.Footnote 3

The hardening of attitudes towards prisoners was evident in two influential commissions of inquiry into convict and local prison systems. The 1863 Royal Commission established to Enquire into the Operation of Transportation and Penal Servitude in Convict Prisons in Britain and Ireland and the 1863 House of Lords Select Committee on Prison Discipline in England (Lord Carnarvon’s Committee) collated detailed evidence from prison governors, medical officers, chaplains and inspectors, and made wide-reaching recommendations for changes in penal policy. The Carnarvon Committee was particularly important; its recommendations shaped legislation, including the 1865 English Prison Act, while the outlook of the witnesses exemplified the tone of late nineteenth-century penal policy and the direction of subsequent legislation. Under new rules introduced from the 1860s onwards, separate confinement remained intrinsic to the English prison system, but became more penal with greater emphasis on the uniform enforcement of hard labour and strict adherence to meagre dietary scales.Footnote 4 To incentivise good behaviour, a version of the mark or ‘stage’ system, which had been a feature of convict prison discipline in Ireland from the 1850s, was introduced to English convict and local prisons allowing for ‘the possibility of [prisoners’] promotion to a less arduous stage by obedience and docility’.Footnote 5 Following the death of Joshua Jebb, Chairman of the Directorate of Convict Prisons, in 1863, Sir Walter Crofton, former Director of the Irish Convict Prisons (1854–62), worked with the Home Office on the 1865 Prison Act, developing a version of the progressive system for English prisons.Footnote 6 There was support for a similarly punitive penal policy in Ireland, although it was not always implemented in the form of legislative changes. The 1865 English Prison Act, for example, was not extended to Irish local prisons. However, from the 1860s, a shift towards a more penal approach characterised the work of the Inspectors General of Prisons, Dr John Lentaigne and J. Corry Connellan, and their successors.Footnote 7

Alarming statistics on recidivism fuelled the growing dissatisfaction with reformist penal policy and advocates of rehabilitation. Increasingly, prison administrators became preoccupied with halting the growth of the prison population and deterring reoffending.Footnote 8 The Habitual Criminals Acts of 1869, shaped by Crofton, introduced harsher sentencing for repeat offenders and extended police supervision of released prisoners in England and Ireland.

There was also a push from senior government and prison officials, notably Sir Edmund Du Cane, Chairman of the Directorate of Convict Prisons, and Crofton, for greater levels of centralisation and uniformity in implementing penal policy and regulations, and this underpinned the reconfiguration of administrative structures and the drive for nationalisation.Footnote 9 The 1877 Prison Acts centralised the English and Irish prison systems, further eroding the autonomy of local bodies, including the Justices of the Peace and Grand Juries responsible for managing local prisons.Footnote 10 In England nationalisation resulted in the establishment of the Prison Commission under Du Cane. Holding the post of chair until 1895, his term was associated with the implementation of strict prison policies and harsh prison conditions, an approach extensively criticised during Gladstone’s 1895 Departmental Committee on Prisons. In Ireland, the 1877 Act created the General Prisons Board, initially chaired by Crofton, who was succeeded in October 1878 by Charles F. Bourke, one of two Inspectors General of Prisons. Bourke’s brother, Richard Southwell Bourke (Lord Naas), was Chief Secretary for Ireland from July 1866 to September 1868, and an influential voice in shaping penal policy.Footnote 11 Among other aims, nationalisation was intended to rationalise prison estates and produce significant economies, and soon after its introduction, several local prisons were closed and staff dispensed with.Footnote 12

Increasingly prison medical officers became more fully occupied in providing medical attention to prisoners and more directly involved in imposing prison discipline. Prison rules outlining the roles of prison surgeons, developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, were tightened in the 1860s and 1870s, as legislation and prison regulations expanded the duties and responsibilities of prison medical officers. As discussed in Chapter 2, the first sets of regulations charged doctors with regularly visiting prisoners and convicts, especially those placed in separate confinement, to watch out for the adverse effects of the regime. The 1865 English Prison Act, directives from the Home Office and the Chief Secretary’s Office, and published rules and regulations for individual prisons, required doctors to attend prisons at least twice a week and to examine each prisoner during these visits.Footnote 13 At Mountjoy Convict Prison, a single full-time resident medical officer, Dr James W. Young, was appointed in 1867 to replace two non-resident medical officers, the high-profile Dr Robert McDonnell at the main prison and Dr Awly Banon at Mountjoy Female Prison.Footnote 14 The status of some appointees became more prestigious. Dr David Nicolson, who worked as Medical Officer at Woking, Portland, Millbank and Portsmouth Prisons before moving to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in 1876, became a leading authority on prison medicine and criminal psychology.Footnote 15 Although there was no direct equivalent to Nicolson in Ireland in terms of his professional profile, after his departure from Mountjoy, McDonnell served on the 1884 Royal Commission on Prisons in Ireland, while Dr Hercules MacDonnell, Medical Officer at Dundalk Prison, published on penal policy and, as discussed below, was a vocal critic of the 1877 General Prisons (Ireland) Act.

More generally, by the second half of the century, prison medical officers were emerging as a discrete professional group, notably in convict prisons, where ‘they had common professional interests, served a common authority, participated in a recognizable career structure, and evolved for themselves a distinct professional ethos’.Footnote 16 Many, like John Campbell and Robert McDonnell, had transferred to prison service following careers in the army and navy, but increasing numbers devoted their entire professional careers, particularly in the convict service, to prison medicine.Footnote 17 In line with an increased emphasis in dealing with mental disorder as an aspect of their workload, a small number moved between employment in criminal lunatic or public asylums and prisons. A prison appointment provided a reliable salary and in some cases accommodation, for some in the locales where they had been raised.Footnote 18 Dr William Ralph Milner, the son of a local surgeon, who qualified in 1838, was employed as apothecary to Wakefield Dispensary before being appointed resident surgeon to the convict department of Wakefield Prison in 1847 at a salary of £200.Footnote 19 The surgeons and doctors employed by local prisons in Ireland had typically served as town dispensary doctors; in 1852 the physician to County Donegal Gaol, Dr Robert Little, had been employed as doctor to the Letterkenny Dispensary, while Dr Thomas Dillon, the magistrate for County Mayo, was the physician for the County Gaol, surgeon to the County Infirmary and former surgeon to Westport Dispensary.Footnote 20

The career of Dr William Augustus Guy, an authority on prison medicine and prison diet, has been summarised in detail by Anne Hardy, who explains that, unlike many of his contemporaries, he came to the prison service with a set of deeply embedded views and principles. He was an established sanitarian, who had served as Professor of Forensic Medicine and then Dean at King’s College London, before taking up the post of Superintending Medical Officer at Millbank Prison between 1859 and 1865.Footnote 21 Guy was responsible for introducing a new dietary to English prisons in 1864, directed at reducing food allowances, and held ‘unyielding views on the discipline required to achieve social justice’, forged by his loathing of idleness and waste.Footnote 22 According to Hardy, the contrast with Dr Robert Gover, who succeeded Guy at Millbank and served as Medical Inspector of Local Prisons and Superintending Medical Officer of Convict Prisons after 1877, was stark.Footnote 23 Commencing as assistant surgeon at Portsmouth in 1857, and then resident surgeon under Guy at Millbank, Gover spent his entire career in the prison service, and was noted for his pragmatic and humane approach.Footnote 24 According to ex-convict Henry Harcourt, who provided detailed evidence to the 1878 Penal Servitude Commission, including details of prison medical officers’ cruelties, ‘a more humane and better man does not exist than Dr Gover’.Footnote 25 Nonetheless, Gover advocated the use of the treadwheel, not least as a guard against shirking, and was vigorous, as shown in Chapter 5, in his efforts to root out the feigning of mental disorder. Dr Patrick O’Keefe, Medical Officer at Spike Island and Mountjoy Convict Prisons from the 1870s, was less popular among prisoners. Prior to his appointment, Inspector Murray had expressed a preference for ‘an Irishman, and one if possible who has had some experience in the practical working of a Poor Law rural district’.Footnote 26 Citing the positive results derived from the employment of Dr James Young, Resident Medical Officer at the Mountjoy Convict Prison, Murray cautioned against a ‘naval or military practitioner’.

These gentlemen … rarely if ever possess that faculty of individualization which should distinguish the medical officer of a convict prison, and they are not habituated to exhibit, whether through feeling or from assumption, the soothing, interested manner which acts so powerfully upon the temperament of the great body of Irish Convicts, whether male or female.Footnote 27

While Young was praised for his kindness, O’Keefe was criticised by Convict E.F. for ‘inhuman cruelty’ in keeping ‘poor maniacs in perpetual cells until reason had become undermined from hunger, flogging, and deprivation of the air of heaven’.Footnote 28

Prison medical officers varied in terms of their commitment to prison work, evidenced by the frequent complaints about their neglect of paperwork, poor record keeping and failure to attend the prison regularly or to absent themselves, noted by magistrates and prison administrators. At Spike Island, Dr Jeremiah Kelly was severely reprimanded by Crofton following the death of a convict who was treated by a hospital attendant in Kelly’s absence. On further investigation, Crofton discovered that Kelly was in the habit of leaving the prison for several hours during the night.Footnote 29 In turn, prison surgeons grumbled about their expanding workloads and inadequate recompense. F.A. Bulley, surgeon to Reading Gaol, complained in 1853 that his quadrupled workload following the introduction of the separate system had not been matched by a salary increase. Caring for 187 prisoners and 22 officers, he received only £80 per annum compared with the surgeon at York who had a similar number of prisoners but was paid £300. In response to Bulley’s request, the magistrates argued that he devolved too much work to his assistant to warrant a salary increase, noted that there were complaints about his tardiness and failure to complete registers and reports, and threatened him with dismissal.Footnote 30 In 1882, the salaries of Irish prison doctors ranged widely from £60 for medical officers at smaller local prison like Castlebar, County Mayo, to £200 for the medical officer at Cork Male and Female prisons, while Young, who served Mountjoy Male and Female Prisons, had a salary of £360.Footnote 31

In the years after nationalisation, new and detailed schedules of responsibilities for prison medical doctors were developed, although positions at local prisons remained part-time and non-residential.Footnote 32 By mid-century epidemic diseases had largely vanished from prisons, but the space this created in terms of prison medical officers’ workloads was amply filled with cases of mental breakdown. Increasingly, doctors were also required to implement and support the prison’s disciplinary practices, to make judgements on the amount of food prisoners required, and determine whether prisoners were mentally and physically fit for labour and punishment.Footnote 33 Dr Quinton claimed in his autobiography outlining his career as a prison medical officer that by the late nineteenth century detailed medical examinations were made on reception and great care taken in assessing prisoners’ ability to undergo hard labour; this, Quinton suggested, represented a sea change and commitment that many long-serving prison surgeons were not willing to accommodate.Footnote 34 Prison regulations also charged prison staff with guarding against the unnecessary infliction of cruelty on physically and mentally ‘weak’ prisoners and with maintaining the health of prisoners within the testing prison environment. Joe Sim contends that the constraints these regulations placed on prison medical officers, often referred to as ‘dual loyalty’, hampered the ability of prison medicine to work either independently or benevolently. It produced tensions between doctors’ status as employees of the prison system and their roles in monitoring and approving the disciplinary aspects of the prison regime, and the obligation to care and lobby for the health of their prisoner patients.Footnote 35 Martin J. Wiener has also highlighted the ‘disciplinary face of Victorian public medicine’, arguing that there was an affinity between Victorian punishment and medicine.Footnote 36 In this chapter, we consider the repercussions of these regulations for medical officers’ management of the mental health of their charges, and ask whether and how deeply medical officers were implicated in the imposition of disciplinary regimes that resulted in or exacerbated mental breakdown. Our research demonstrates significant variation in the ways individual prison medical officers working in England and Ireland implemented discipline and responded to mental breakdown among prisoners, a topic examined in detail in the second section of this chapter.

Simultaneously, medical and psychiatric opinion on the nature and cause of criminality became more penal in the late nineteenth century, as faith in the potential for reform began to evaporate. Penologists and social commentators were disheartened by failed efforts to reform and rehabilitate, and they were, like prison administrators, alarmed about the high level of reconviction. By the late nineteenth century, seeking explanations for past failures and new ‘remedies’, penologists and psychiatrists researched and published on scientific criminology and the relationship between crime, degeneracy and mental unfitness. Rejecting the theories of Caesar Lombroso and other continental criminologists on the ‘born criminal’, they emphasised the ways in which criminology in the British Isles varied in approach.Footnote 37 Criminologists and psychiatrists in England and Ireland did not, as Forsythe has shown, ‘begin to search around for human apes or tribal types for they did not apply a rigid theoretical framework to their descriptions’.Footnote 38 Rather, as Campbell’s comments at the opening of this chapter demonstrate, they imperfectly absorbed a version of positivist science and evolutionary theories as they became disillusioned with reform. By the 1880s they, along with other social commentators, began to argue that criminality and mental capacities were ‘relative constitutional fixedness’.Footnote 39

This chapter also assesses the implications of the altered medical and penal landscape for the mental condition of prisoners in local and convict prisons in late nineteenth-century England and Ireland. While McConville has acknowledged that concerns about the relationship between disciplinary regimes and mental distress in local prisons influenced penal policy, there has been limited analysis of the implications of the refashioning of prison discipline on the minds of prisoners.Footnote 40 Wiener has argued that after the debates on the relationship between the separate system of confinement and mental breakdown in the 1830s and 1840s, interest in and commentary on the issue dissipated until the 1870s.Footnote 41 Yet disquieting rates of mental disorder continued to be reported in local and convict prisons and were discussed in various official inquiries examining prisons and penal policy as discipline was strictly enforced after the 1860s.

This chapter examines the changing role of the prison medical officer and considers whether the constraints of dual loyalty, alongside overwhelming workloads in environments ill-suited to medical and psychiatric care, overpowered the potential of medical officers to pursue regimes mindful of prisoners’ wellbeing, instead becoming ‘integral to the control and disciplinary apparatus of the modern prison’.Footnote 42 The first section examines the debates around the implementation of changes to penal policy in the late nineteenth century, with a particular focus on the contributions of influential prison medical officers as well as senior prison officials and reformers. It investigates whether those charged by the state with responsibility for prisons and for the minds of prisoners were troubled by the gap between the stated aim of penal policy – that the ‘ordinary condition’ of prisoners did not allow gratuitous suffering or danger to life and health – and the reality of the institutions they managed. It also considers whether, as penal policy evolved, there was debate and conflict among prison administrators regarding their responsibilities for prisoners’ mental wellbeing.

The second section of the chapter focuses on medical expertise and knowledge production, and assesses the responses of English and Irish prison doctors to the positivist turn in the field of criminal justice and the specific problem of the habitual criminal in terms of their day-to-day practices. Assessments of English criminology by Neil Davie, Stephen Watson and others have focused on debates on the theories of the criminal mind, and the feeble-minded, and how they could be traced, observed and defined.Footnote 43 Our sources, which, alongside official reports, include the archives of individual prisons, underline the challenges presented to medical officers by the ‘lunatic criminal’, in a context shaped increasingly by anxiety about the rise in recidivism, high prison populations and failure to reform. Medical officers became ever more assertive in identifying themselves as experts in prison medicine, and, as Chapters 4 and 5 also explore, in understanding and dealing with mental illness in prison. As Hardy has pointed out, this was challenging work. ‘I am completely at the mercy of these men,’ Brixton Prison’s Medical Officer noted in 1882, alluding to the lack of cell accommodation for ‘troublesome mental cases’.Footnote 44 Most prison medical officers received little formal or practical training in psychiatry and few had experience of working in lunatic asylums.Footnote 45 Yet, as the second section of this chapter demonstrates, prison medical officers formulated a specific taxonomy and classification of mental illness related to lunatics who were also criminals. Local and convict prisons became sites of knowledge production, as prison medical officers developed distinct medical categorisations, which embedded prisoners’ criminality and ‘criminal natures’ in their mental conditions and states. We draw on prison medical officers’ descriptions and correspondence about their prisoner patients, and on what became an extensive medical journal literature, which oftentimes dealt deftly and dismissively with continental criminal anthropology, before moving on to the practicalities of management, and to individual cases and examples to explore the everyday management of mental health in prison.

I The Hardening of Penal Policy and Practices

Diet, Labour and the Separate System of Confinement

The two major parliamentary commissions of 1863, reviewing prison regimes in local and convict prisons, encapsulated the shift in tone and approach to late nineteenth-century penal policy. Throughout the 1850s the rigour of the separate system as implemented in convict prisons had been toned down under Jebb’s chairmanship of the Directors of Convict Prisons, and prisoners’ mental and physical health was reported to have improved under this modified regime.Footnote 46 Some early adaptations of the separate system had aroused criticism, not least an experiment at Reading Gaol, implemented by Chaplain Field and aimed at enhancing prisoners’ reading and comprehension skills. It was fiercely criticised by the Visiting Justices and Prison Inspectors, and in 1854 penal labour was reasserted at the gaol.Footnote 47

In 1857 and 1864 amendments to the Penal Servitude Acts sought to reinforce the disciplinary regimes in convict prisons. With the death of Jebb in 1863, an influential barrier to the assertion of punitive and deterrent disciplinary ethos in convict prisons was removed.Footnote 48 More stringent implementation of the separate system of confinement was advocated, with the 1863 Royal Commission on Transportation and Penal Servitude concluding that penal servitude was not ‘sufficiently’ dreaded. Witnesses noted, for example, that the average convict spent less than nine months in separate confinement and insisted that the period of separation be implemented fully and ameliorated only when there was a threat of physical or mental injury to convicts.Footnote 49 The Commission recommended reversing many of the modifications introduced in the 1850s and advocated for the introduction of separation for able-bodied convicts at the public works prisons at Chatham, Portsmouth, Portland and Gibraltar, and Dartmoor and Woking Invalid Prisons.Footnote 50 The system of granting marks or credit for good conduct adopted in Irish and English convict prisons was criticised as was the practice of granting convicts marks for diligence in Irish prison schools.Footnote 51 The Commissioners noted differences in the administration of penal servitude legislation in England and Ireland, and commended the ‘formidable’ rendering of the separate system under Crofton’s system in Ireland. In addition to the operation of intermediate prisons, and the supervision of holders of tickets of leave, in terms of the implementation of the separate system during the probationary stage at Mountjoy, they specifically praised the lower, meat-free diet provided during the first four months in separation and limiting work to oakum picking in the first three months.Footnote 52 These rigorous elements of the separate system, they argued, increased the ‘wholesome effect’ on the minds of prisoners.Footnote 53 The Commission sought greater severity in sentencing penal servitude convicts, the introduction of the ‘progressive’ or ‘mark system’ in English prisons, and tighter implementation of the separate system. Colonel Edmund Henderson, who succeeded Jebb as Chairman of the Directorate of Convict Prisons in 1863, implemented many of these recommendations; the provision of ‘extra diets’ was prohibited except on medical grounds, hammocks in separate cells were substituted with plank beds, and convicts were to spend the full nine months in separation except in cases of serious injury to mental or physical health.Footnote 54

Lord Carnarvon’s 1863 Select Committee was particularly important in shaping policy in local and borough county prisons. Witnesses were quizzed on the high levels of recidivism among prisoners, poorly trained staff and substantial variations in the implementation of regulations. Prison inspectors and other medical and lay experts on penology identified local prisons as particularly problematic, repeatedly criticising them for failing to impose rigorous and uniform systems of discipline, though it was acknowledged that sentences in local prisons were too short for the full application of the separate system. They were also accused of overfeeding prisoners and lax supervision of ticket-of-leave prisoners.Footnote 55 When published, the recommendations of the Carnarvon Committee reinforced the social function of prison while its reformative aim was downplayed.Footnote 56 The ‘moral reformation of character’, Carnarvon insisted, was ‘greatly assisted by a preliminary course of stringent punishment’.Footnote 57 While retaining the separate system as the basis for penal discipline in local prisons, Carnarvon sought to configure specific elements of the regime, notably prison labour, diet and the environment of the cell, to heighten the punitive experience.Footnote 58

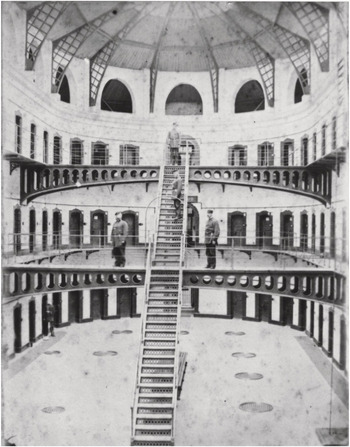

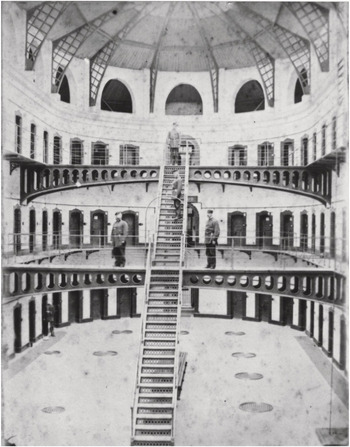

Carnavon’s recommendations set the tone for debate on local prisons across England and Ireland, and specifically shaped the English Prison Act of 1865.Footnote 59 In Ireland, Corry Connellan, Inspector General for Prisons, advocated in 1863 for the introduction of many of the committee’s recommendations to local prisons. He helped draft a Prisons (Ireland) Bill in 1866, which, if implemented, would have consolidated legislation relating to prisons in Ireland and introduced elements of the 1865 English Prison Act.Footnote 60 The Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Naas, was an influential proponent of the bill, but, while reaching a second reading in the House of Lords, it fell foul of the extremely busy parliamentary sessions in 1866 and 1867 and did not pass into legislation. Nonetheless, the separate system was scheduled for implementation in local prisons as provision expanded in the 1860s, including the opening in 1863 of a new east wing with over 100 cells for separate confinement at Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin (Figure 3.1).

The remit of the Carnarvon Committee was wide-ranging, and specific aspects of penal discipline, notably what constituted hard labour, prison diet and the conditions and implementation of separate confinement, were forensically examined. The effectiveness of these aspects of prison discipline was debated during subsequent inquiries into English and Irish penal policy over the next three decades, including the 1878 Commission on the Penal Servitude Acts (the Kimberley Commission), and the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons, which reviewed the implementation of prison legislation in local and convict prisons. Primarily concerned with balancing the punitive and reformative aims of imprisonment, prison officials, penologists and a small number of ex-prisoners debated the deleterious impact of the new disciplinary regimes on prisoners’ physical and mental health in their evidence to these inquiries. In addition, as the duties of prison medical officers were reconfigured and bolstered, some medical officers highlighted the challenges of aligning their roles and responsibilities in safeguarding the mental health of prisoners with the increasingly penal approach of the prison environment.

The push for uniform and rigid application of prison discipline across the prison estate in the 1860s and 1870s was partly a response to high-profile reports, including those of physiologist and social reformer, Dr Edward Smith, that highlighted the uneven implementation of prison discipline.Footnote 61 In the late 1850s Smith had surveyed the effects of prison discipline on prisoners’ health in English county gaols, and his analysis of the dietary requirements of prisoners on hard labour were submitted to the Carnarvon Committee and published in the final report.Footnote 62 His work, reported in the Lancet in 1858, revealed uneven enforcement of hard labour across the English prison estate, and in some instances he found ‘no labour at all’.Footnote 63 Smith observed disparities in the types of labour designated as hard labour; in one prison, ‘oakum-picking was no labour … and hard labour in another’.Footnote 64 He also claimed women were placed at the crank and treadwheel in some prisons, although George Laval Chesterton, Governor at Cold Bath Fields Prison in Clerkenwell, had complained that women, who ‘could not expect the same chivalrous sympathy accorded to their more morally upright sisters’, did not work at the treadwheel.Footnote 65 Considering the implementation of the separate system in local prisons, Smith reported strict enforcement of all elements in some prisons, including prisoners being compelled to wear masks when moved around the prison, while elsewhere ‘hundreds of prisoners sit together in the room picking oakum’.Footnote 66 He also drew attention to the varied punishments inflicted on prisoners, noting unequal application of corporeal punishments including whipping by officers using the ‘cat’.Footnote 67 In his evidence to the Carnarvon Committee, Smith sought absolute uniformity of prison punishments, and claimed prisoners were idle for long periods of each day. He suggested they perform not less than 7½ or 8 hours of work a day when serving hard labour sentences, and a minimum of 10 hours a day for other prisoners.Footnote 68

The imprint of Smith’s findings can be identified throughout the report and recommendations of the Carnarvon Committee, which rejected oakum picking, and forms of industrial occupation, originally intended to improve prisoners’ minds as well as punish them, as ‘light’ or ‘immediate’ labour, and only accepted punitive work at the treadwheel and crank as ‘hard labour’ proper (Figure 3.2). Shot drill was permitted when local authorities needed to supplement the treadwheel and crank.Footnote 69 In designating these three forms of work as ‘hard labour’, they explicitly rejected the positive impact of industrial labour on prisoners’ minds as ‘much less penal, irksome, and fatiguing’ in favour of punitive hard labour intended to make prisoners’ experiences more unbearable.Footnote 70 In Ireland, Connellan advocated Carnarvon’s recommendations, lamenting the lack of ‘punitive labour’ in local prisons, which, he argued had been imperfectly replaced by industrial labour, a change he dismissed as futile. With the publication of the Report of the Carnarvon Committee, he sought its reintroduction to county prisons, and suggested the separate system be extended to prison hospitals to prevent communication among patients.Footnote 71

Figure 3.2 Middlesex House of Correction: male prisoners on treadmill. Wood engraving by W.B. Gardner, 1874, after M. Fitzgerald

Several witnesses to the Carnarvon Committee were troubled by some of the proposals. Dr John George Perry, Inspector of Prisons for the Southern and Western Districts and the Medical Inspector of Prisons in England and Wales, emphasised the dangers of the treadwheel to prisoners’ health. He sought its abolition ‘on account of the inequality of its operation’, ‘its injurious effect upon the health of many of the prisoners’, and ‘when unproductive, a waste of labour which might be better bestowed’.Footnote 72 Major William Fulford, Governor at Stafford Prison, however, suggested to the committee that he already had the powers to impose a deterrent and severe regime, which in his view should combine hard labour with a low diet and use of the whip:

If I had the means of giving every man who is sentenced to hard labour in Stafford prison the full amount of discipline I am empowered to do by Act of Parliament, for two years, no man alive could bear it: it would kill the strongest man in England.Footnote 73

Other witnesses referred specifically to the ‘irritating’ impact of the crank and treadwheel on the minds of prisoners, with some prisoners finding unproductive work ‘disheartening’, ‘depressing’ and leading them to despair.Footnote 74

Nonetheless, work at the treadwheel was selected as the preferred form of hard labour and prison officials sought its implementation across local prisons. In Ireland, there was variation in the form of hard labour depending on conditions at individual gaols, and the treadwheel was not systematically introduced. However, by 1880, it was implemented at Castlebar, Clonmel, Richmond, and Galway and Cork Male Prisons. At other local prisons, male inmates picked rope junk or oakum, worked at shot drill, which, according to Priestley, was virtually ignored in English local prisons, or broke stones.Footnote 75 In prisons with a sizeable female population, such as Belfast, Kilmainham, Cork and Grangegorman, women usually worked at picking rope or oakum.Footnote 76 After nationalisation those confined at Mountjoy Male Prison were employed at mat making and picking coir in cells, while convicts in Mountjoy Female Prison made bedding and clothing, and did the laundry for other prisons and institutions.Footnote 77 By 1882, however, Frederick Richard Falkiner, Recorder of Dublin, criticised the continued use of the treadwheel and shot drill in some prisons, as well as ‘the almost valueless oakum and hair picking, and the mat making’ in others.Footnote 78 Alongside the deferral of legislative reforms, for him the persistence of such prison labour was evidence of the deterioration of the Irish system, once praised as ‘the best solution of the convict problem, and a model for imitation in Europe and America’.Footnote 79

Most parliamentary commissions on prisons were preoccupied with the relationship between prison diet, punishment and discipline, and several witnesses highlighted the potentially negative effects of reduced diet on the minds of prisoners. Jebb stressed the importance of a ‘good diet’, which Reverend W.L. Clay had dismissed as ‘belly bribes’ for prisoners serving long sentences at Pentonville Prison in his evidence to Carnarvon’s Committee, arguing it counteracted the ‘depressing influences of separate confinement’.Footnote 80 An advocate of separate confinement, Jebb insisted the separate cell had a ‘very corrective effect upon the mind of a prisoner’.Footnote 81 As early as 1849, as discussed in Chapter 2, Jebb had, however, become concerned that a severely reduced diet could damage the mental as well as physical health of convicts.Footnote 82 Dietary modifications to reduce costs at Wakefield Prison, he claimed, were a false economy given that ‘imprisonment injudiciously prolonged after unequivocal symptoms of failing health had appeared or an insufficiency of diet’, rendered the convicts mentally and physically depressed and unfit for transportation, and was thus a long-term drain on prison resources.Footnote 83 Two years earlier, William Milner, Medical Officer at Wakefield Prison, had become concerned about the ‘unmanageable’ delusions among prisoners in separate confinement, and in response had increased dietary allowances and periods of exercise, modifications that appeared to have benefited the prisoners.Footnote 84

The importance of a ‘sufficient’ diet was stressed by Inspector Perry, who commented on the restorative and medicinal use of diet by prison surgeons not only to ‘treat disease but to prevent it’. He sought extra dietary allowances to restore the constitutions of enfeebled and physically debilitated prisoners, especially vagrants.Footnote 85 Nonetheless, there were those who advocated for sparser dietary scales, including Fulford at Stafford, on the grounds that prisoners on shorter sentences were not required to perform hard labour.Footnote 86 Concerns about prisoners becoming too enfeebled and physically incapacitated to work on release, the threat of epidemic disease outbreaks in prisons, and maintaining prisoners’ capacity to perform labour, prompted the Carnarvon Committee to defer any proposals for a national, uniform dietary scale for local prisons, and concluded that prison diet was not to be used as an instrument of punishment.Footnote 87

The quality and quantity of prison diet in Ireland was also scrutinised in the 1860s. As in England, diet in local prisons was sparser than in convict prisons; nonetheless, these dietary scales had been criticised for their generosity when compared to the diets of the average agricultural labourer, workhouse dietaries and the sparser diets implemented in English local prisons. A lower dietary scale was introduced in 1849, and further reductions implemented in 1854 for prisoners aged fifteen years and under, to align prison and workhouse diets for that age group.Footnote 88 Cautioning against further reductions, in 1863 the Irish lawyer and politician Edward Gibson insisted that once a fair, ‘sufficiently penal’ diet had been agreed, diet should be ‘regarded as a medical question’. ‘The system of starving crime into surrender’, Gibson argued, if it went below the limit necessary for health, would prompt expensive hospital admissions, with prisoners liable to become burdens on the rates once released. Consequently, the ‘superiority’ of prison food ‘must again be asserted’.Footnote 89 The 1863 Commission on Transportation and Penal Servitude recommended that the practice of not providing meat during the first months in separation in Irish prisons be extended to English convict prisons, and, while they did not advocate for the reduction of diet for convicts working in association in public works prisons, they suggested some experimentation ‘to ascertain whether any reduction can safely be made’.Footnote 90

From 1863 the disciplinary regime applied to penal servitude convicts in separation became more punitive, and by 1878 the Kimberley Commission concluded that the sentence was ‘generally an object of dread to the criminal population’.Footnote 91 Dietary privileges, including those allowed at Mountjoy Convict Prison, were abolished and the reduced diet for convicts during the first three months of their sentences was enforced.Footnote 92 These changes prompted concern from penologists, including Crofton, who defended the relatively generous dietary scales for convicts against criticism from the Board of Superintendence of Dublin City Prisons on the grounds that convicts were required to preform hard labour.Footnote 93 In 1863, Reverend Charles Bernard Gibson, Chaplain at Spike Island, also warned against reducing convict diets further, but he reasoned that depriving convicts of employment during their first months in ‘solitary cells’ was more damaging as it deprived ‘the mind of its proper food’.Footnote 94 Responding to these concerns, a medical committee, comprising the eminent physician Dr William Stokes, Dr John Hill, the Poor Law Medical Inspector, and Dr William M. Burke, Medical Superintendent at the General Register Office, were appointed to inquire into dietary scales in Irish county and borough gaols.Footnote 95 On their recommendation, in 1868 prison governors were ordered to improve the quality of the food.Footnote 96 In their final published report, the commissioners highlighted the tensions inherent in the role of the prison surgeons. It was, they noted, inconsistent ‘with the character and the objects of medical science, that the Surgeon should be compelled to watch for the time when the punishment can be no longer endured, and so virtually to become, in his own capacity, an assistant to the execution of a sentence’.Footnote 97

The nationalisation of both prison systems under the 1877 Prison Acts reopened the debate on prison diet. The Acts enabled prison boards to further enforce the punitive and disciplinary regimes in both convict and local prisons. Rationalisation, frugality and disciplinary rigour preoccupied Du Cane and Charles Bourke, and Du Cane established a scientific committee on prison diet, which reported in February 1878.Footnote 98 Comprising Henry Briscoe, Inspector of English Prisons, Dr Robert Gover, Medical Officer at Millbank Prison, and C. Hitchman Braddon, Medical Officer at Salford Hundred County Prison, it was charged with considering whether changes to prison discipline brought in under the 1877 Act necessitated new dietary scales, especially in cases when the period prisoners spent at hard labour was reduced. The committee members framed imprisonment as a ‘physiological rest’ when the ‘struggle for survival is suspended’, with prisoners guaranteed food and other necessities. Considering the psychology of prisoners, they contended that ‘Tranquility of mind and freedom from anxiety are leading characteristics of his [the prisoner’s] life. From the moment that the prison gates close behind him, the tendency, in most cases, is to lessened waste of tissue; he lives, in fact, less rapidly than before.’Footnote 99 Labour exacted on inmates in local prisons, they argued, was not ‘excessive’, while ‘wholesome’ work, whether mental or physical, was not normally lethal. ‘Worry’, however, was more dangerous, as it was a ‘rust, which eats into the blade and destroys it’, although prisoners, ‘as a rule’ were free from it.Footnote 100 The committee’s published report repeatedly referenced the ‘mental peace’ and tranquillity of life in prison, which was characterised as a protected and insulated existence, with prisoners free from the emotional strife that can ‘exhaust the vital energies’ in everyday life. The prisoner ‘rarely experiences domestic grief or disappointment; and, as a general rule, he has no pride capable of receiving a wound’.Footnote 101 While briefly acknowledging that ‘the restraints of discipline’ and the loss of liberty could be irksome and a ‘severe trial’, and ‘that what appears to us to be peace and order may to the inmates be often indistinguishable from gloom and monotony’, the overall tone of the report minimised the difficulties of prison life.Footnote 102 Deviating from the 1868 recommendations of the medical committee on Irish dietary scales, Du Cane’s committee did not highlight any potential tension in the role of the prison medical officers and instead reiterated the importance of the judgement of the prison doctor in deciding whether prisoners should be allocated extra allowances of food.Footnote 103 The committee recommended that prison medical officers retain discretionary power to approve extras, and, while noting that diet should not be diminished where health was damaged, they cautioned against prison doctors allocating too liberal a diet.Footnote 104

A modified version of English prison diet, scheduled for Irish prisons under the 1877 Prison Act, was delayed owing to disagreement among the Irish medical profession on its suitability. However, a second medical commission, established by the Irish General Prisons Board in 1880, concluded the new scales were ‘sufficiently liberal’. As with the English commission, they agreed prison doctors should be permitted to make minor alterations for ‘diseased’ prisoners, but disapproved ‘of any interference with the dietary scales as laid down for healthy prisoners’.Footnote 105 They also introduced amendments to the convict prison diets at Spike Island and Mountjoy Male and Female Prisons.Footnote 106 The 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons claimed that changes to prison diet contributed to increased expenditure.Footnote 107 Nonetheless, the Commission recommended enhanced dietary allowances for specific classes of prisoners owing to the inferior bodily condition of Irish prisoners, whose previous habits, poor quality of foodstuff and their ‘generally low physical condition of health render them more susceptible to the effects of prison discipline’.Footnote 108 Despite earlier attempts by the General Prisons Board to halt such practices, the Commission noted that medical officers frequently prescribed improved diets as a prophylactic against illness among ‘juvenile offenders, nursing mothers, and aged prisoners … although as a matter of fact such prisoners are in excellent health’.Footnote 109

While debates on prison diet and the implementation of hard labour dominated discussions of penal discipline in the late nineteenth century, other aspects of prison discipline, which affected prisoners’ mental and physical health, were critically reviewed, including hammock-style bedding, which had been used in separate cells since the implementation of the separate system. Following Carnarvon’s recommendations, hammocks, believed to be too comfortable, a ‘self-indulgence’, were replaced with plank beds usually without any mattress, for inmates serving the first stage of sentence.Footnote 110 Inspector Perry, however, warned against their widespread use, as they caused repeated sleepless nights and impaired mental and physical health.Footnote 111 In 1884 the leading Irish nationalist parliamentarian Charles Stewart Parnell, who viewed prison diet and the treadwheel as too severe a punishment, noting the ‘semi-starved’ aspect of the prisoners at Kilmainham Gaol, described the plank bed as a ‘punishment attended with physical torture’.Footnote 112 Society, Parnell argued, was not entitled ‘to enfeeble the bodies of prisoners in order to reform their minds, or with a view of maintaining discipline amongst them’.Footnote 113 Dr Hercules McDonnell, echoing Parnell in his objection to the plank beds, insisted ‘punishment should not include cruelty, nor should it impair health’. He argued against their use ‘in long term sentences … from a moral point of view. It engenders a mental state of resistence [sic] to authority, and renders the prisoner less amenable to discipline or the better influences which ought primarily to be cultivated.’Footnote 114

MacDonnell was one of many detractors of the revised disciplinary regimes of the 1860s and 1870s and the relentless drive to impose a uniform punitive system. Witnesses at Carnarvon and subsequent committees cited the potential damage the harsher disciplinary regimes could inflict on prisoners’ spirits, and ultimately their minds, and their implementation elicited further debate on the link between the separate system of confinement and incidences of mental disorder and distress in prisons. In their critiques, prison medical officers, chaplains and other prison officials explicitly connected mental disorder among prisoners and convicts to the new punitive prison regimes, and modified versions of the separate system were introduced to some local prisons in England and Ireland. Proponents of the new penal regimes, meanwhile, persistently argued that many prisoners entered prison predisposed to mental weakness and were constitutionally unable to withstand its rigour or benefit from it, rather than blaming the regime for prompting mental breakdown and insanity.

In 1863 a number of key prison administrators, including Inspector Perry, Herbert Voules, the Inspector for the Northern District, and Edward Shepherd, Governor at West Riding Prison, Wakefield, objected to various measures proposed for local prisons, citing the potential for damage to the minds of prisoners. Perry, for example, contended that prisoners found unproductive labour such as the treadwheel and the crank demoralising, degrading and irritating, having a ‘prejudicial effect on the temper of the men’ and ‘resulting in ‘insubordination produced by irritation and despair’.Footnote 115 Jebb, who acknowledged the ‘depressing influence’ of unproductive labour, also downplayed it, insisting that ‘some prisoners will resist anything that is disagreeable to them’.Footnote 116 Such commentary highlighted an enduring ambiguity: on the one hand, prison administrators commented on the harm inflicted on prisoners by prison discipline and environments, and, on the other hand, demonstrated a persistent faith in the overall efficacy of prison discipline and in the separate system. Voules agreed that ‘unproductive employment’, such as the treadwheel, led to the degradation and irritation of the minds of prisoners and that separation was a ‘severe punishment’ to prisoners.Footnote 117 Yet he insisted that the separate system was ‘the only safe foundation of prison discipline … it forces a man to reflect; it makes him feel that employment is a boon … and it separates him from [the] contaminating influence of other prisoners’.Footnote 118 In 1863, Jebb suggested the ‘depressing influences’ of separation were partly a consequence of the reduced amount of exercise required of convicts while working at a trade, but that ‘any deleterious effect’ on prisoners would be mitigated with sufficient fresh air and exercise.Footnote 119 Dr Clarke at Pentonville, however, noted that prolonged periods in separation produced a ‘debilitating effect upon men’, and in 1870 observed that the moral influence of solitary confinement was, ‘if not hurtful to the mind, at least negative for good’.Footnote 120 However, defending the separate system, Dr William Guy, Medical Superintendent of Millbank Prison, observed:

Our system of separate confinement does not appear to affect the mind injuriously. I do not mean to say that a prisoner who comes into prison upon the verge of unsoundness of mind, might not develop into full unsoundness in that time, partly because of the separation; but I am of opinion, also that a prisoner should expect that this may happen to him, and that the possibility of unsoundness must be taken into account as one of the results of his being in prison at all.Footnote 121

Irish prison staff showed similar disquiet and ambivalence. In 1862 Dr Maurice Corr, Medical Officer at Philipstown Prison, which housed a large number of invalids, noted the ‘great irritability and total destitution of self control’ among prisoners whose ‘mental disease’ was ‘generated and fostered in prison’, while Michael Cody, Roman Catholic chaplain at Mountjoy Male Prison, objected to subjecting prisoners to separate discipline for eight months.Footnote 122 Disagreeing with the Directors of Convict Prisons in 1869, at a time when the prison population at Mountjoy had declined by two-thirds, Cody argued ‘that to subject the prisoners to the separate discipline for eight months is calculated to injuriously affect them mentally as well as physically’ as the regime had ‘the effect of gradually causing depression of spirits, nervousness, eccentricity, and causing, what is most to be deplored, loss of that controlling power by which man governs his imagination, course of thought, and inferior appetite’.Footnote 123

Despite these concerns, and the disastrous experiences at Pentonville in the 1840s, in the late nineteenth century support for separate confinement remained entrenched among senior prison officials. Medical Inspector Dr Gover, commenting favorably on conditions in Millbank Prison in 1870, noted that among the 27 convicts certified as insane, 25 were sick on admission and two had histories of mental illness. Defending the disciplinary regime, he observed that ‘No case came under my observation, of which it could be said that the mental disease had been brought on by the discipline of the prison.’Footnote 124 In 1874 Millbank’s chaplain described separate confinement, ‘as the only chance’ of bringing prisoners under ‘moral or religious influence’, insisting the prison’s regime had no injurious mental or physical consequences. While acknowledging that strict implementation of separation for the whole sentence of penal servitude was harmful, he advocated in favour of minimum association among prisoners as ‘the most successful in its reformatory and deterring effects on the criminal’.Footnote 125

Despite Hercules McDonnell’s criticisms, there was greater acknowledgement during the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons of the dangers the separate system posed to prisoners’ minds. Captain John Barlow, Director of Irish Prisons, under questioning from Dr George Sigerson, conceded that ‘The cellular discipline of Mountjoy would I suppose tend to develop insanity.’Footnote 126 Sigerson claimed ‘the number of male convicts becoming insane at Mountjoy would exceed three times’ the number found in prisons that were not operating the separate system.Footnote 127 The final report criticised prison medical officers for failing to rigorously examine prisoners on reception to identify incipient diseases, especially symptoms of mental illness, and recommended reception wards be provided in prisons to allow for the close observation of prisoners on admission. With early identification such prisoners could be quickly removed to hospitals, or carefully observed, and so ‘prevent the infliction of punishment for breaches of discipline committed by prisoners suffering from nervous irritability, who really are more properly subjects for medical treatment than for punishment’.Footnote 128

‘A Servant of the Board’? Medical Officers and Prison Practices and Regimens

While the degree of uniformity originally sought by senior prison officials, including Du Cane, was never realised, cumulatively the legislative and policy changes of the 1860s and 1870s had a striking impact on prison life and prisoners. McConville has suggested that conditions in English local prisons were especially harsh with little support for the reformative objective of imprisonment. For inmates the prison environment became more taxing, rigorous, and in some instances brutal, especially in prisons that were overcrowded, insanitary and the physical infrastructure dilapidated.Footnote 129 Conditions in Irish local prisons were likewise severe, and, in terms of sanitation, often dangerous, though, as Beverly Smith has argued, it is unclear whether these conditions reflected a coherent penal policy or the General Prisons Board’s bad management.Footnote 130 Officers in some local prisons struggled to maintain discipline and order, and their efforts to implement prison regimes could be fierce and relentless, especially when managing irritable, destructive and violent prisoners, many of whom were described as mentally ill-equipped and unable to withstand prison discipline. There were also instances of neglect, cruelty and poor management by badly trained staff.

As noted above, the 1865 English Prison Act tightened regulations to ensure regular medical visitations to local prisons, while in the early 1860s individual boards of superintendence of county gaols in Ireland published bye-laws and detailed schedules of doctors’ duties and responsibilities. Overall in both settings, these expanded regulations required prison medical officers to attend prisons regularly, to examine every prisoner each week, and to visit daily sick prisoners on extra diet and those confined in punishment cells, recording treatments in journals and report books. They were also required to attend prison staff and their families, to supervise and train hospital warders, inspect the entire prison building on a regular basis, report structural faults in prison ventilation and drainage, and to assess the quality of bedding, clothing and food, and when necessary, implement public health measures to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.Footnote 131 They were also to investigate prisoner deaths. Finally, the regulations enforced doctors’ active involvement in the administration of prison discipline, requiring them to adjudicate on prisoners’ fitness for hard labour and punishments. The regulations specifically outlined prison medical officers’ duties in terms of safeguarding the minds of prisoners, and watching for signs of mental deterioration or other adverse health effects related to the disciplinary regime. Doctors were to report cases to the prison governor with directions for treatment, which usually included extra food and exercise. They were also permitted to consult medical advisors from outside the prison. These duties and regulations not only placed prison doctors under considerable pressure, they also involved them in the disciplinary aims of penal regimes, regardless of whether or not they endorsed these.

Many prison doctors in England and Ireland, like prison governors, transferred from military careers into the prison service and would have been used to a working environment that stressed discipline and order, though increasingly by the second half of the century they devoted their entire careers to prison medicine. They pressed regularly for improved conditions and salaries, framing these requests as being beneficial to the prisoners they cared for. In Ireland, the Association of Gaol Surgeons, with Dr Hercules MacDonnell as Honorary Secretary, was formed to lobby for the interests of the profession as the duties of prison medical officers were expanded under the 1877 Act without, they argued, appropriate remuneration.Footnote 132 In 1882, these duties, as originally laid out in the legislation, were partly amended, but the Association continued to pursue a campaign against the General Prisons Board, lasting several years. Acrimonious and bitter, it highlighted the hostility prison doctors felt towards the Board, which was accused of ‘insidious encroachment’, ‘illiberality’ and ‘attempted bullying’.Footnote 133 To improve relationships, the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons recommended the appointment of a Medical Inspector to the General Prisons Board, and a year later Dr Frederick McCabe, Local Government Inspector, commenced in post. Though complimentary about McCabe, the Medical Press and Circular claimed that he and the prison ‘medical department’ had been ‘subordinated’ by making the post holder ‘a servant of the Board’, compromising McCabe’s capacity to act and comment independently.Footnote 134

In much of their early correspondence with local prison governors, the General Prisons Board vigorously enforced new prison rules, demanding that prison officers, including surgeons, adhered to the new orders, prompting the resentment of prison medical officers.Footnote 135 Medical officers were frequently admonished for interfering with or ignoring the decisions of the Board, and exceeding their powers. In May 1880, following the death of prisoner J. Connors after an attempted suicide, the Board rebuked the Governor at Waterford Prison for exhibiting ‘a great want of judgment … in not requiring the prisoner to be visited frequently during the night after he had been placed in muffs & that it was considered he attempted suicide’.Footnote 136 The Board subsequently drafted a circular requiring that prisoners under mechanical restraint be visited at night and medical officers called on to regularly attend prisoners who attempted suicide.Footnote 137

The work of medical officers was complicated further by varied prison populations and conditions for inmates. While it is unlikely that the many prisoners serving short sentences spent prolonged periods in separation, its implementation remained the aim of prison officials.Footnote 138 As some English prisons were closed or amalgamated, others saw a rise in numbers and overcrowding in the late nineteenth century. Liverpool Borough Prison had a particularly large number of female committals, many ‘professedly prostitutes’.Footnote 139 On 20 September 1869, 1,097 male and female convicts were confined in 1,001 cells certified for separate confinement at Liverpool and two-thirds of the 12,785 admissions that year were recommittals.Footnote 140 The persistent problems of overcrowding and reoffending among female prisoners had first emerged in the 1850s.Footnote 141 By 1877, the prison’s Roman Catholic minister, Reverend James Nugent, an ardent temperance reformer, observed that among the 4,571 females under his charge in that year, only 648 had never before been in prison.Footnote 142 Some 1,310 were committed after being found drunk or accused of riotous conduct, and 1,555 for disorderly behaviour on the streets. Nugent, in his final report for the prison before his retirement, observed:

Drink is making terrible havoc upon the female population of this town; not only demoralizing the young, and leading them step by step into crime and the lowest depths of vice, but destroying the sacred character of family life, and changing wives and mothers into brutal savages.Footnote 143

Flagging up the close association between excessive drinking and mental breakdown, Nugent observed that ‘Not a week passes without some one being brought to the prison whom drink has maddened and robbed of all female decency, whose language and actions are so horrible that they seem no longer rational beings, but fiends.’Footnote 144 In 1898, Dr W.C. Sullivan and Dr Stewart Scholar, the latter Deputy Medical Officer at Liverpool Prison, reported on the link between alcoholism and suicidal impulses as revealed in 142 cases of persons charged with attempted suicide and remanded in Liverpool Prison. They argued that women’s ‘generative organs’, were ‘peculiarly susceptible to the alcoholic poison’, which produced ‘emotional alterations of the personality’ that could prompt suicidal tendencies.Footnote 145

In Ireland, the local prison population declined in the decades immediately after the Great Famine. In his evidence to the 1878 Commission on the Penal Servitude Acts, Reverend Lyons, Roman Catholic Chaplain at Spike Island, when pressed on whether he believed prison discipline acted as deterrent, was ambivalent and instead argued that during the Great Famine ‘The kind of people who were convicted were peasantry who had no notion of ever committing a crime.’Footnote 146 Nonetheless, there was anxiety about high rates of reoffending. The Inspectors General of Prisons in Ireland, concerned at the expansion of the local prison population, noted a 5.5 per cent increase in committals between 1862 and 1863, when they totalled 33,940, highlighting a rise in short sentences and a troubling growth in recommittals especially among women.Footnote 147 Frederick Falkiner observed in 1882 that among prisoners in custody for the January quarter of his court sittings, 76 per cent of the male prisoners had previous convictions; the average was five each while three had been imprisoned more than twenty times.Footnote 148 Among women the average number of previous convictions was seventeen.Footnote 149 Falkiner further noted that ‘with these unfortunates, men and women, the coming and going in this world is from the streets to the prison, from the prison to the streets, and back again with the certainty of recurrent tides – more contaminating and more contaminated with every flux and reflux’.Footnote 150

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, there was a ‘remarkable decrease’ in the size of the English and Irish prison populations.Footnote 151 Yet, while the overall figures supported claims that there was ‘a decline in the spirit of lawlessness’, the high rates of recommittals, especially for minor offences such as those related to alcohol, remained a cause of disquiet among prison officials.Footnote 152 At some prisons, not least Liverpool, the sheer size of the prison, combined with frequent overcrowding, the large numbers of prisoners on short sentences, and the high rates of recommittals, especially among women, prompted harsh responses from overburdened prison staff, including its medical officers working to rigorously implement new prison regulations.Footnote 153 In 1866, the Visiting Justices imposed work on the treadwheel or crank as first-class hard labour of the ‘most penal kind’ for able-bodied male adults, employing extra officers to enforce this. Other prisoners, including women, were set to oakum picking.Footnote 154 By 1868, prisoners were placed on the treadwheel for five hours during the first month of their sentence, and Liverpool’s Governor subsequently increased this to six hours a day, and then seven hours.Footnote 155 The treadwheel accommodated forty-five prisoners who were compelled to ascend 9,240 feet daily, and by 1876 a daily average of 148 male prisoners worked on it.Footnote 156

For prisoners, especially those serving their first sentences, hard labour was felt keenly, and authors of prison memoirs and some prison officials highlighted its mental as well as physical toll. In 1850, William Hepworth Dixon evoked the mental anxiety associated with hard labour, ‘the dull, soughing voice of the wheel, like the agony of drowning men – the dark shadows toiling and treading in a journey which knows no progress – force on the mind involuntary sensations of horror and disgust’.Footnote 157 Uninitiated prisoners dreaded the treadwheel and were said to find it ‘very irksome and severe’; in his evidence to the 1878 Kimberley Commission, Captain Henry Kenneth Wilson, Governor of Maidstone Gaol, described it as a ‘very unfair punishment’.Footnote 158 The Manchester Merchant, confined to Kirkdale Gaol in the late nineteenth century, ‘pitied the treadwheel men as they went out to their labour’; after a spell on it, it was not unknown for ‘big, strong fellows’ to be ‘led away crying’.Footnote 159 ‘One Who Has Tried It’, who served time in a local prison in England in the 1890s, referred to being in a ‘bath of perspiration’ and feeling ‘quite crushed’ when he returned to his cell after his first experience on it.Footnote 160 Governor Wilson, however, ‘noted that experienced prisoners preferred the wheel to picking oakum’, which was a dirty, slow job.Footnote 161 The rope was covered in tar and the strands were difficult to prise apart. Usually set as ‘task’ work, inexperienced prisoners fell behind, resulting in punishments, reduced diet or loss of marks, prompting intense feelings of mental anxiety.Footnote 162 Experienced prisoners shared ‘tricks’ to mitigate hard labour; one prisoner advised ‘One Who Has Tried It’ on how to ride the treadwheel, ‘to sway the body from right to left’ and allow the ‘rising wheel to assist the upward movement’, and explained he should use a nail, smuggled into the cell, for oakum picking.Footnote 163

Prisoners’ capacity to withstand hard labour was also related to their physical condition when committed, and in the late nineteenth century, prison staff and penologists commented on a marked deterioration in prisoners’ physical and mental states, with many ill-equipped to withstand the regime. The Liverpool Visiting Justices estimated that 10 to 15 per cent of prisoners were ‘unfit for hard labour of first class on account of bodily health’.Footnote 164 Considering the zeal at Liverpool for the new prison regime and for maximising the use of the treadwheel, this may have been a conservative assessment. Dr Francis Archer, Surgeon at Liverpool, who was responsible for assessing all prisoners, noted in 1869 that one-fifth of prisoners – 399 out of 2,023 – sentenced to hard labour on the treadwheel were unfit and excused from hard labour on medical grounds.Footnote 165 Acknowledging that hard labour at Liverpool was of a ‘more severe character’, Archer and Governor Jackson did not introduce the new dietary scales proposed by the Carnarvon Committee.Footnote 166

At Wakefield Prison, the ‘physical tests’ introduced by the Visiting Justices to assess the condition of prisoners demonstrated they ‘were now in feebler condition, bodily and mental, than had been the case some years back’.Footnote 167 In 1871, the prison surgeon reported prisoners’ health as ‘good’, noting only ‘one suicide, three pardons on medical grounds, and three cases of insanity’, who had been found insane after admission and removed to a lunatic asylum.Footnote 168 Three years later, there were two suicides, and twelve removals to the lunatic asylum, an increase from ‘an average of three for the previous seven years’.Footnote 169 At Liverpool, the prison surgeon reported ‘11 deaths from natural causes, and one case of suicide by hanging, and three pardons on medical grounds’ in 1876.Footnote 170 The General Prisons Board also commented on the impoverished state of Irish prisoners in the 1870s, noting their poor physical and mental conditions and linking them to bad harvests and the agrarian distress of 1879 and 1880.Footnote 171 In 1886 Dr Hercules MacDonnell noted that

our criminals suffer from periods of semi-starvation, prolonged fits of intoxication, bad housing, clothing, and many other hygienic defects, it can be readily understood why prison regime does not cause any appreciable deterioration. Cleanliness, regularity, and a sufficiency of food account for this.Footnote 172

Similar comments were made about ‘the deterioration of female criminals’ in the late nineteenth century, with Miss Pumfrey, Lady Superintendent at Winchester convict refuge, acknowledging in 1878 that most of her charges were habitual criminals ‘the residuum … of the criminal population’.Footnote 173 In Liverpool particular concern was expressed at the persistently high numbers of female admissions, well over half, 12,518 of the 21,602 admissions in 1884.Footnote 174 Efforts to rehabilitate ‘unhardened’, young female prisoners centred on releasing them into female refuges run by religious orders. At Liverpool Nugent, inspired by his campaign to protect young women against ‘vicious lives’, removed Roman Catholic women to a Magdalen Asylum run by the Good Shepherd religious order and to similar institutions in Canada.Footnote 175 Towards the end of their sentences, women were transferred to the convict refuges at Winchester and Goldenbridge, Dublin, run by Protestant and Roman Catholic religious orders.Footnote 176 While the refuges in England only held prisoners, a ‘principal point’ of the Goldenbridge institution was that convict women mixed with women who had never been sentenced, a system Du Cane doubted to be beneficial for the ‘free’ women.Footnote 177

Refuges were intended to imitate the workings of the intermediate prisons for men, with the women prepared for release through work.Footnote 178 In England female convicts were transferred to refuges nine months prior to discharge while in Ireland they were transferred for a sixteen-month period. The Sisters of Mercy, the order that managed Dublin’s Goldenbridge refuge, refused the admission of infirm convicts from Mountjoy on the grounds that physical illness added to the difficulties in reforming women, while the burden of accommodating sick, infirm prisoners added to expenses.Footnote 179 Such women, apparently small in number, were released on licence, which Barlow implied was preferable to languishing in a refuge too infirm to work.Footnote 180 Even with the establishment of female refuges, opportunities for reform and rehabilitation were limited, especially as most women served short prison terms.Footnote 181

Given the enfeebled condition of male and female prisoners, medical officers questioned the utility and impact of repeated punishments for misdemeanours and bad behaviour in terms of prisoners’ mental health. They queried whether repeated punishments were an effective means of forcing prisoners to amend behaviour, or of convincing them to accept imprisonment as an appropriate sanction for their crimes. Medical officers adjudicated on prisoners’ fitness to undergo punishments, including the implementation of bread and water diets, confinement in dark cells and inflicting corporeal punishment while also guarding against unnecessary cruelty. Prison visiting justices, governors, surgeons and chaplains were required to be alert to the ‘mind or body of prisoners[s] injuriously affected by discipline or treatment’, while at Liverpool the governor was to ‘see that all insane prisoners are removed from prison as speedily as the law allows’.Footnote 182 As the 1867 medical commission on diet in Irish prisons noted, however, the speed with which prison doctors and others intervened to protect the mental and physical health of prisoners was determined by rules that permitted them to do so only when injury or impairment had been inflicted.Footnote 183

In 1866, Dr Robert McDonnell at Mountjoy Male Prison, who would later describe himself as leaning ‘too much towards the side of humanity’, argued that prolonged punishments could have a ‘maddening effect’, the prisoner is ‘irritated by it; and if there is any tendency to mental disease, this irritation becomes highly injurious’.Footnote 184 Chaplain Cody, commenting on the decline in the number of punishments in 1869, noted: ‘to punish a man for petty infractions of rules, arising from human infirmity, inadvertence, strong provocation, or other extenuating cause, has an evil effect on the minds of the majority of the convicts. When the prisoner was treated like a man, and he conducted himself like a man; he was docile and manageable.’Footnote 185 Often prisoners who attempted suicide had been repeatedly punished for disruptive behaviour, including earlier suicide attempts. Patrick Byrne, a twenty-one-year-old prisoner who commenced his sentence of six months’ hard labour for larceny at Clonmel Prison on 2 June 1887, committed suicide one month later by hanging himself with a bed strap tied to one of the bars of his cell window. He had been placed on a punishment diet on five different occasions in June for talking to other prisoners. The coroner’s inquest found that he had been temporarily insane at the time of the attempt although the medical officer did not refer to any abberant behaviour in his report.Footnote 186 These difficult and disruptive prisoners refused to comply with prison discipline, and were repeatedly punished, sometimes over several years. While a minority of cases were transferred to asylums, for the most part they were suspected to be cases of malingering and carefully observed by the medical officers.Footnote 187

The difficulties faced by prison medical officers in managing disruptive and dangerous behaviour among prisoners, often related to mental illness, were highlighted in an inquest report into the death of a convict at Spike Island in 1870. The convict had died of ascites, and, according to the report of the Medical Press and Circular, the jury had expressed, ‘in the strongest terms, their “total disapproval of the frequent punishment he suffered in cells, on bread and water for several days in succession, during his imprisonment in Spike Island”’.Footnote 188 The unnamed convict had been transferred by McDonnell from Mountjoy Prison as unfit for cellular discipline, but not as an ‘invalid’ although he had been suspected of suffering from epilepsy. McDonnell had kept him in the prison infirmary for several months as the ‘only means of keeping him from the system which might have been injurious to him’.Footnote 189 Defending the actions of Dr Jeremiah Kelly at Spike, the Medical Press and Circular noted that Kelly had not received the ‘convict as a sick man, nor had he any reason to know that he was unfitted for the usual bread-and-water discipline of Spike Island’.Footnote 190 The article also reflected on the difficult position of Kelly and McDonnell in relation to the prison authorities when advocating for or protecting the health of their charges. Citing the example of McDonnell, described as ‘an inconveniently compassionate medical officer’, who, they argued, had been removed from his position at Mountjoy for the ‘fearless discharge of his duty’ in defending untried Fenian prisoners from excessive punishment, the article speculated that the same fate might befall Kelly had he countermanded orders to punish the convict. The jury’s censure of Kelly, ‘for undue severity of punishment’, provided, they argued, the opportunity for prison authorities ‘to shift their responsibility to Dr Kelly and expurgate themselves by throwing him overboard’.Footnote 191 The article sought enhanced protection for prison medical officers who, in discharging their duties and responsibilities in relation to prisoners, were liable to be ‘McDonnellized’ or made to ‘suffer for official sins’.Footnote 192

The new rules introduced after nationalisation heightened the anxieties of Irish prison medical officers who argued that the regulations further compromised their capacity to protect the ‘health of prisoners under their charge’.Footnote 193 In a submission to the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons, the Association of Gaol Surgeons highlighted the tension between surgeons’ responsibilities to their prisoner patients and ensuring the disciplinary function of prison sentences was not ‘unduly mitigated’.Footnote 194 They also emphasised the potential damage to professional reputations should they miss cases of malingering.Footnote 195 The Association’s Honorary Secretary, Dr Hercules MacDonnell, expanded on these points in his address to the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland in May 1885, which was also forwarded to the General Prisons Board and published in the Daily Express.Footnote 196 MacDonnell stressed that while ‘neither the diet nor surroundings should be such as to make imprisonment agreeable … punishment should not include cruelty, nor should it impair health’.Footnote 197 In his review of prison regimes in Belgium, Germany and Italy, published in 1886, he reiterated the point that ‘Punishment must be deterrent. Loss of personal liberty and deprivation of all usual enjoyments act under this head. Under no circumstances should this partake of the character of vengeance.’Footnote 198