Differential risk effects of season of birth have been reported for several diseases, raising the possibility that early environmental exposure in utero and during infancy may influence the risk in adulthood. Seasonal trends of birth have been established for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children (Sorensen et al, 2001a), early-onset non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (Reference Langagergaard, Norgard and MellernkjaerLangagergaard et al, 2003), breast cancer (Reference Kristoffersen and HartveitKristoffersen & Hartveit, 2000), testicular cancer (Reference Prener and CarstensenPrener & Carstensen, 1990), Crohn's disease (Reference Sorensen, Pedersen and NorgardSorensen et al, 2001b ), coronary heart disease (Reference Lawlor, Davey Smith and MitchellLawlor et al, 2004) and brain tumours (Reference Brenner, Linet and ShapiroBrenner et al, 2004). In their reviews, Castrogiovanni et al (Reference Castrogiovanni, Iapichino and Pacchierotti1998) and Torrey et al (Reference Torrey, Miller and Rawlings2000) found that more patients with schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy and narcolepsy are born in December and January, whereas affective disorders, alcohol dependence, autism, dyslexia, and multiple sclerosis are reported more frequently in those born during spring and summer months. Month of birth has also been linked to human longevity (Reference Doblhammer and VaupelDoblhammer & Vaupel, 2001). However, few studies have investigated the effect of month of birth on suicide rates. Huntington (Reference Huntington1938) reported that the distribution of birth month for those who died by suicide was different from those who did not. Pokorny (Reference Pokorny1960) found an overrepresentation of suicide cases in which the person was born in the month of July. Kettl et al (Reference Kettl, Collins and Sredy1997) reported variations in season of birth for suicide among Alaskan natives, with more suicide deaths in those born in the summer. Chotai & Asberg (Reference Chotai and Asberg1999) reported that people born in winter in Sweden were significantly more likely than those with other birth seasons to have used hanging as a suicide method. Using 12-year suicide data from Cheshire, UK, an increased risk of violent suicide, particularly hanging, among people born in the summer was found by Salib (Reference Salib2002), quite the opposite of the Swedish study. However, the above studies share some major methodological limitations, including small sample size, lack of controls and the use of inappropriate statistical methods.

This study examines the association between suicide and season of birth using routinely collected suicide data over a 22-year period in England and Wales. The size of the database used in this study provides a powerful opportunity to assess this issue, with nearly 27 000 suicides from over 11 million births, and greatly exceeds the size of all previous studies.

Our hypotheses were that the risk of suicide would vary according to month of birth and that this association would remain after adjusting for the effects of the total number of births per month in the population. We also predicted that this differential in risk of suicide by month of birth would be present when looking at suicides by gender and method of suicide (violent and non-violent).

METHOD

Our study was an observational one using routinely collected data. Counts of suicides (ICD–9 codes E950–959; World Health Organization, 1977) and undetermined injury deaths (ICD–9 codes E980–989), reported in England and Wales between 1979 and 2001 and separated by gender, were obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Total monthly births for the period 1955–1966 for people who reached age 16 years and above in the period 1979–2001 were also obtained from the ONS. The nationally collected database was accepted as reliable and as complete as would be possible.

The term ‘suicide’ used in this study includes all cases of suicide (ICD–9 codes E950–959) and undetermined injury deaths (ICD–9 codes E980–989) combined in order to reduce misclassification biases.

Sample selection

National suicide data in England and Wales between 1979 and 2001 recorded 124 661 suicides: 86 566 (69%) verdicts of suicide and 38 095 (31%) open verdicts. A total of 26 915 suicides completed between 1979 and 2001 by people born between 1955 and 1966 were selected for our analyses. Data on month and year of birth and death, method of suicide and gender were available. The number of births of people who did not die by suicide during the study period (control group) was obtained by subtracting monthly births of the suicide sample from monthly population births between 1955 and 1966. There were 11 035 365 births of people who reached at least 16 years of age in England and Wales in this period.

Data analysis

The total number of suicides of people born in the period 1955–1966 was aggregated according to month of birth into monthly counts. Monthly frequencies of births and suicides were adjusted to 31-day months. The number of births of the suicide group in each month was divided by the number of total births in England and Wales for the same period to obtain birth rates for the suicide group. For reasons of confidentiality the database only included information on gender, method, months and years of birth and death, thus we calculated the age at death as completed months.

In the analyses, ‘violent’ methods of suicide included hanging, drowning, falling from height, shooting, burning, asphyxia and wounding; poison by solids or liquids and poison by gas were regarded as ‘nonviolent’ methods.

Statistical method

Previous studies have used chi-squared tests to analyse seasonality data. However, since these tests cannot detect complex cyclical trends efficiently (Reference EdwardsEdwards, 1961; Reference Bradbury and MillerBradbury & Miller, 1985; Reference Yip, Chao and ChiuYip et al, 2000), and suicide is a rare event among the general population, we fitted generalised linear models (GLMs) with Poisson and negative binomial responses and logarithmic links. Overdispersion was formally assessed using a likelihood ratio test comparing Poisson and negative binomial models, taking into consideration the problems of testing at boundary values (Reference Cameron and TrivediCameron & Trivedi, 1998). Trends by year of birth were adjusted using cubic splines with three effective degrees of freedom; this functional form was deemed complex enough to model these trends by minimising Akaike's information criterion (AIC). Seasonal variation was modelled using at most three harmonic components in order to have enough flexibility to detect asymmetrical seasonal variations which would be lost if only one symmetrical 12-month cycle had been fitted. The seasonal components used had 12-month, 6-month and 4-month periods: the first accounts for symmetrical yearly cycles, and the last two were included in order to allow the detection of asymmetrical yearly patterns. The models considered also included interaction terms between year of birth, gender and method of suicide with the seasonal components in order to allow for possible differences in their shape. The final models presented were selected by minimising AIC and, as in all stepwise-type model selection procedures, correlation among the parameter estimates may produce misleading results – for instance, entered variables can be proxies for others. The final models have a large number of parameters, and some of the effects that appear to be significant when comparing the parameter estimates to their standard errors may be spurious. The analyses of deviance tables for each of the final models are shown in the Appendices presented as a data supplement to the online version of this paper. All calculations were carried out using R version 2.0.0 (R Development Core Team, 2004) in a Windows environment. The negative binomial GLMs were fitted using the MASS library (Reference Venables and RipleyVenables & Ripley, 1998).

RESULTS

There were 26 915 incidents of suicide in England and Wales by people over 16 years of age born between 1955 and 1966 during the 22-year data collection period 1979–2001; of these, 21 103 (78.4%) were men and 5812 (21.6%) were women. Table 1 shows the number of suicides between 1979 and 2001 by year of birth and the mean age at death by gender. It includes 29 cases with no month of birth available, for which age at death was calculated as number of completed years; these cases were excluded from the analysis of seasonal patterns. After adjusting for seasonal trends, there was no significant difference in the age distribution by gender.

Table 1 Age distribution by birth year and gender of people who died by suicide 1979–2001

| Birth year | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean age (years) | n | Mean age (years) | |

| 1955 | 1630 | 35.3 | 523 | 35.2 |

| 1956 | 1695 | 34.6 | 500 | 33.9 |

| 1957 | 1710 | 33.6 | 561 | 33.3 |

| 1958 | 1640 | 33.0 | 477 | 32.6 |

| 1959 | 1729 | 31.9 | 535 | 31.5 |

| 1960 | 1686 | 31.1 | 505 | 31.0 |

| 1961 | 1824 | 30.4 | 460 | 29.8 |

| 1962 | 1819 | 29.5 | 530 | 29.5 |

| 1963 | 1916 | 28.9 | 476 | 29.0 |

| 1964 | 1968 | 28.5 | 436 | 28.6 |

| 1965 | 1805 | 27.7 | 423 | 27.3 |

| 1966 | 1681 | 27.2 | 386 | 26.5 |

| Total | 21 103 | 30.9 | 5812 | 30.9 |

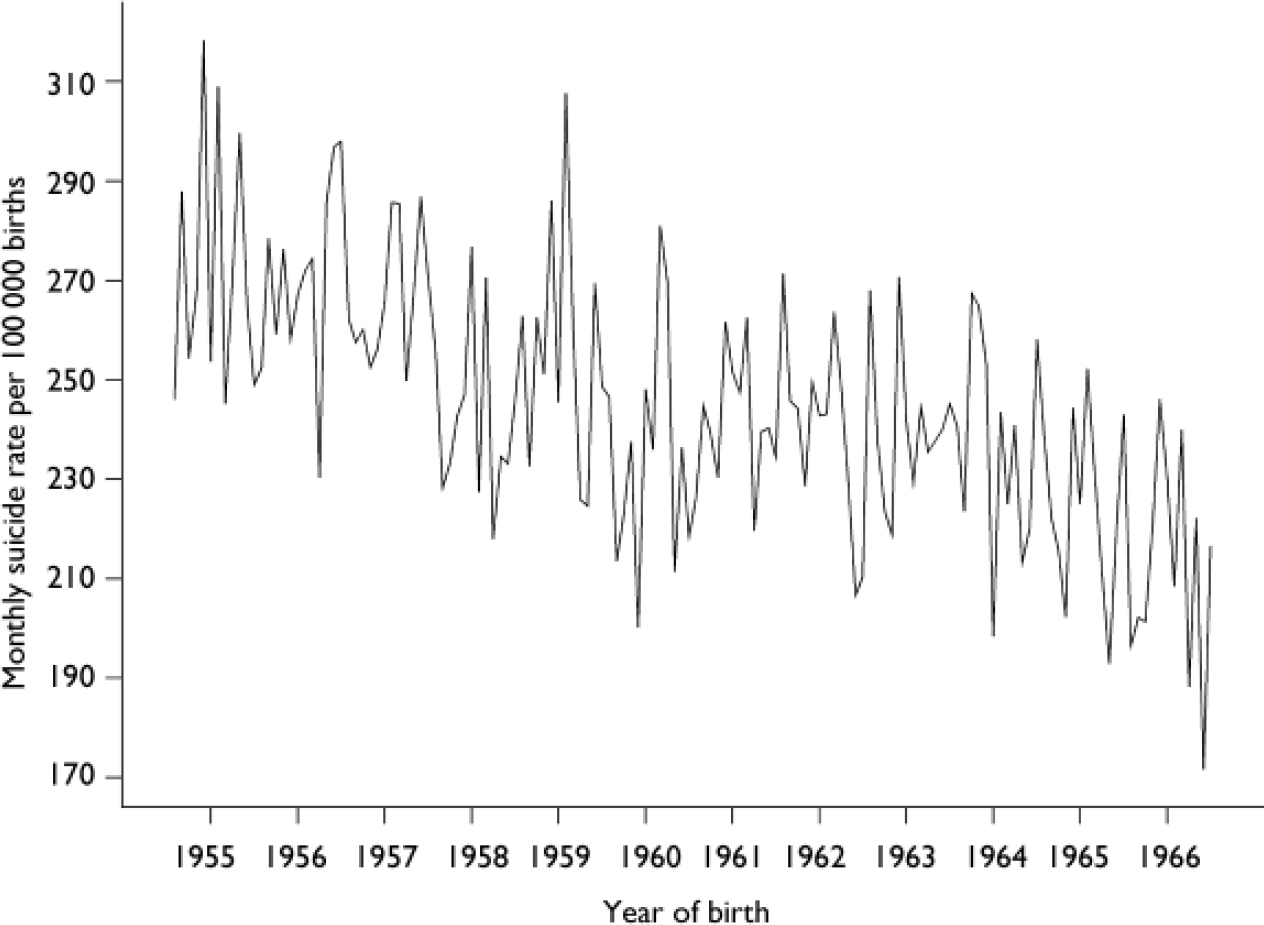

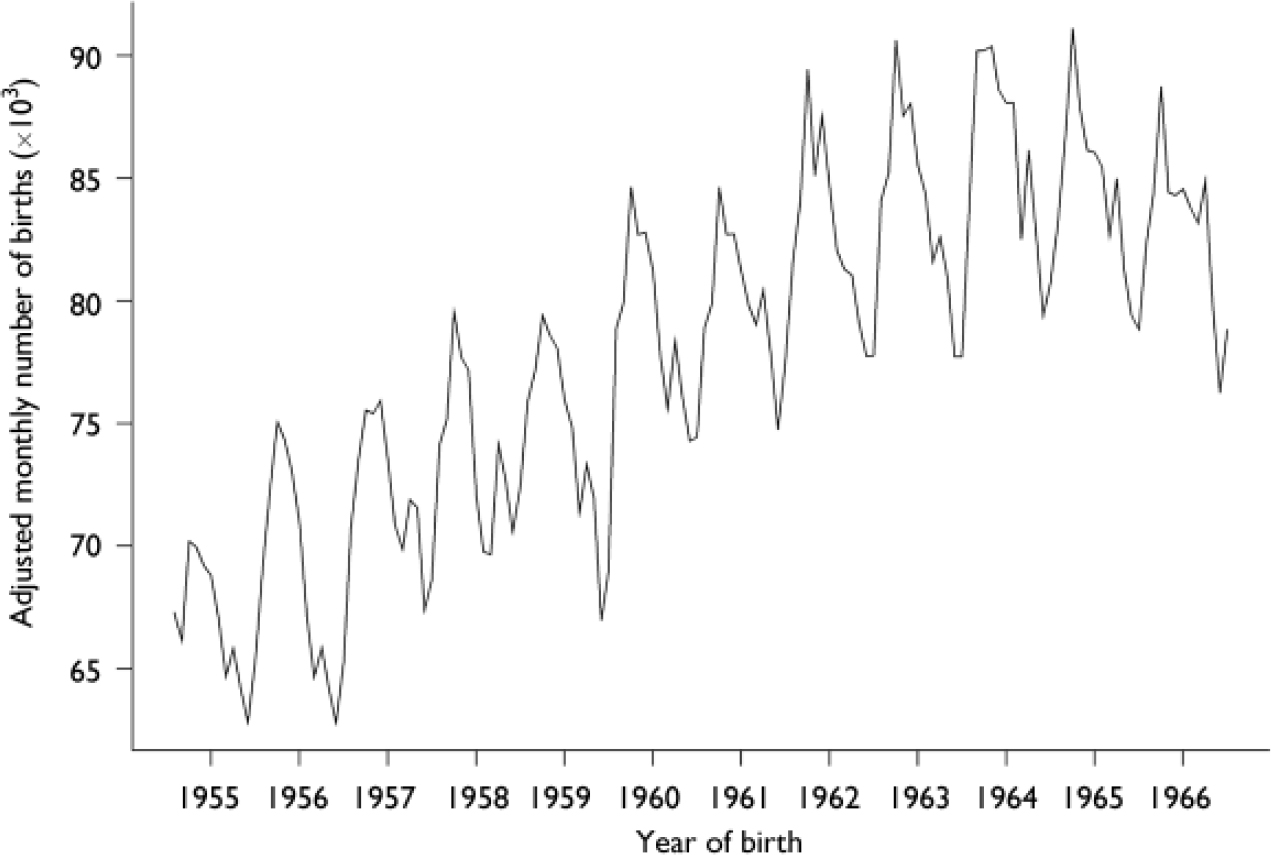

Figure 1 shows the monthly suicide rates for people aged over 16 years born between 1955 and 1966 who died by suicide between 1979 and 2001. Figure 2 shows the adjusted monthly number of births for people who did not die by suicide who were born between 1955 and 1966: this is the control population. There is a steady increase in the number of births up to 1962, followed by a period of slower growth. The beginning of the series exhibits the so-called European seasonal pattern (Reference ParkesParkes, 1976) in the distribution of monthly number of births, with a large majority occurring in the spring with a subsidiary peak in September; the latter part of the series shows the start of the shift to the American pattern, with a pronounced peak in September. The transition to this seasonal pattern was complete in England and Wales by the late 1970s. The two series are not stationary and have distinct, albeit different, seasonal patterns with annual peaks and troughs in the monthly birth rates.

Fig. 1 Monthly suicide rate of people born between 1955 and 1966 who died by suicide between 1979 and 2001.

Fig. 2 Adjusted monthly number of births between 1955 and 1966 for people who did not die by suicide between 1979 and 2001.

Analysis of all suicides

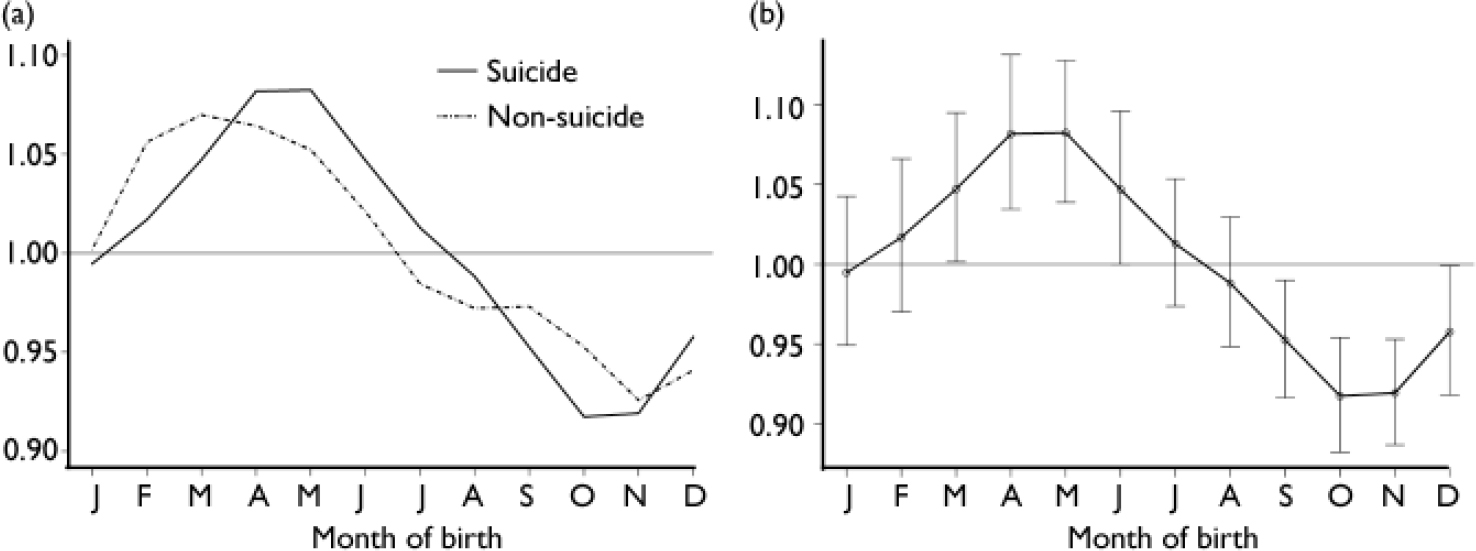

Mean age at suicide was 30.3 years; there was no significant difference in the age distributions by gender. Generalised linear models for negative binomial responses with a logarithmic link function were fitted since there was significant (P < 0.001) overdispersion in the Poisson models. A forward stepwise approach was followed adding seasonal components with 12-month, 6-month and 4-month periods, as well as interactions among them, the secular trend, and the factor indicating whether or not the person had died by suicide. The final negative binomial model for all suicides (see Appendix 1 in the data supplement to the online version of this paper) has 14 parameters and models the numbers of births resulting in suicide and nonsuicide. Its most significant terms were the difference in frequencies between suicide and non-suicide cases, the trend of year of birth, the 12-month and 6-month harmonic terms (P < 0.00001) and the 4-month harmonic terms (P < 0.003). The interaction terms corresponding to the difference between suicide and non-suicide cases and the 12-month and 6-month seasonal components were also significant (P=0.013, 0.037). The last two terms account for the different shapes in the (symmetrical and asymmetrical) seasonal patterns corresponding to suicide (peak in early summer) and non-suicide (peak in spring) frequencies. The trend by year of birth was significantly different in the suicide and non-suicide groups, as indicated by the interaction terms (P < 0.00001), and the seasonal component with period 12-month changed significantly with year of birth (P < 0.0001), reflecting the start of the change to the American pattern in the monthly numbers of births. Figure 3(a) shows the detrended monthly seasonal components for suicide and non-suicide cases as a fraction of their means. The significant excess of suicides in early summer births and the deficit in autumn are evident. Figure 3(b) shows the detrended monthly seasonal components as a fraction of their mean for suicides with upper and lower bounds of 95% confidence intervals. Adjusting for the year of birth, the model predicts that the average increase in risk of suicide between the trough (October) and the peak (May) of the seasonal component is 17.9% (95% CI 13.0–21.8).

Fig. 3 Mean detrended seasonal components for suicide and non-suicide cases (a) and for suicide cases with confidence intervals of prediction (b).

Analysis by gender

Since overdispersion was significant in the Poisson regressions, we fitted negative binomial GLMs. The final model was obtained using the same model selection strategy as above and included 33 parameters (see Appendix 2 in the data supplement to the online version of this paper). The term corresponding to the difference between suicide and non-suicide frequencies had the following significant interactions:

-

(a) a 4-way interaction with gender, year of birth trend and the 4-month seasonal component (P=0.027);

-

(b) two 3-way interactions: with gender and year of birth trend (P < 0.001), and with gender and the 4-month seasonal component (P=0.016);

-

(c) interactions with both gender and year of birth trend (P < 0.001 in both cases).

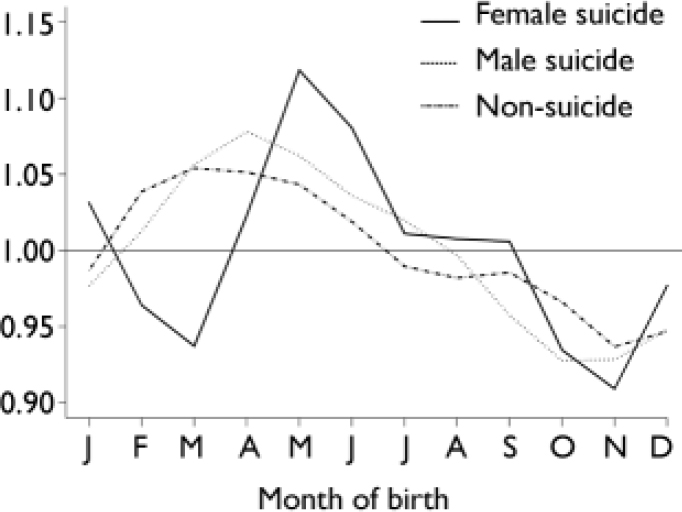

The strongest main effects were those of the suicide and non-suicide contrast, gender, year of birth trend, and the 12-month and 6-month seasonal components (P < 0.001 in all cases). These interactions establish the different patterns by gender in the asymmetrical cycles determined by month of birth for the suicide cases once the effect of year of birth is adjusted for. Figure 4 shows the detrended seasonal components by gender for male and female suicide and non-suicide cases as a fraction of their means. This model supports the hypothesis of different seasonal phenomena by month of birth for both men and women who die by suicide. Monthly births of men who died by suicide showed a roughly symmetrical pattern, with one trough in autumn and one peak in late spring; for women who died by suicide the seasonal pattern was definitely asymmetrical, with troughs in late winter and early autumn, and a main peak in midsummer taking place slightly later than the peak for men, and a secondary, significant peak in early winter. The average increase of risk between the autumn trough and the summer peak of the detrended seasonal components was 29.6% (95% CI 8.0–50.7) for women and 13.7% (95% CI 5.2–22.2) for men, thus reflecting both the larger number of men dying by suicide and the stronger effect of seasonal variation of month of birth on women completing suicide. The higher birth rates in the spring and early summer for people who die by suicide suggest that some weather variables may be important, and there appears to be a positive deviation from the detrended monthly births of the suicide group coinciding with the annual increase in temperature and sunshine hours during the same months. This was not evident in those who were born during the same period but did not die by suicide.

Fig. 4 Mean detrended seasonal components by gender.

Analysis by method of suicide and gender

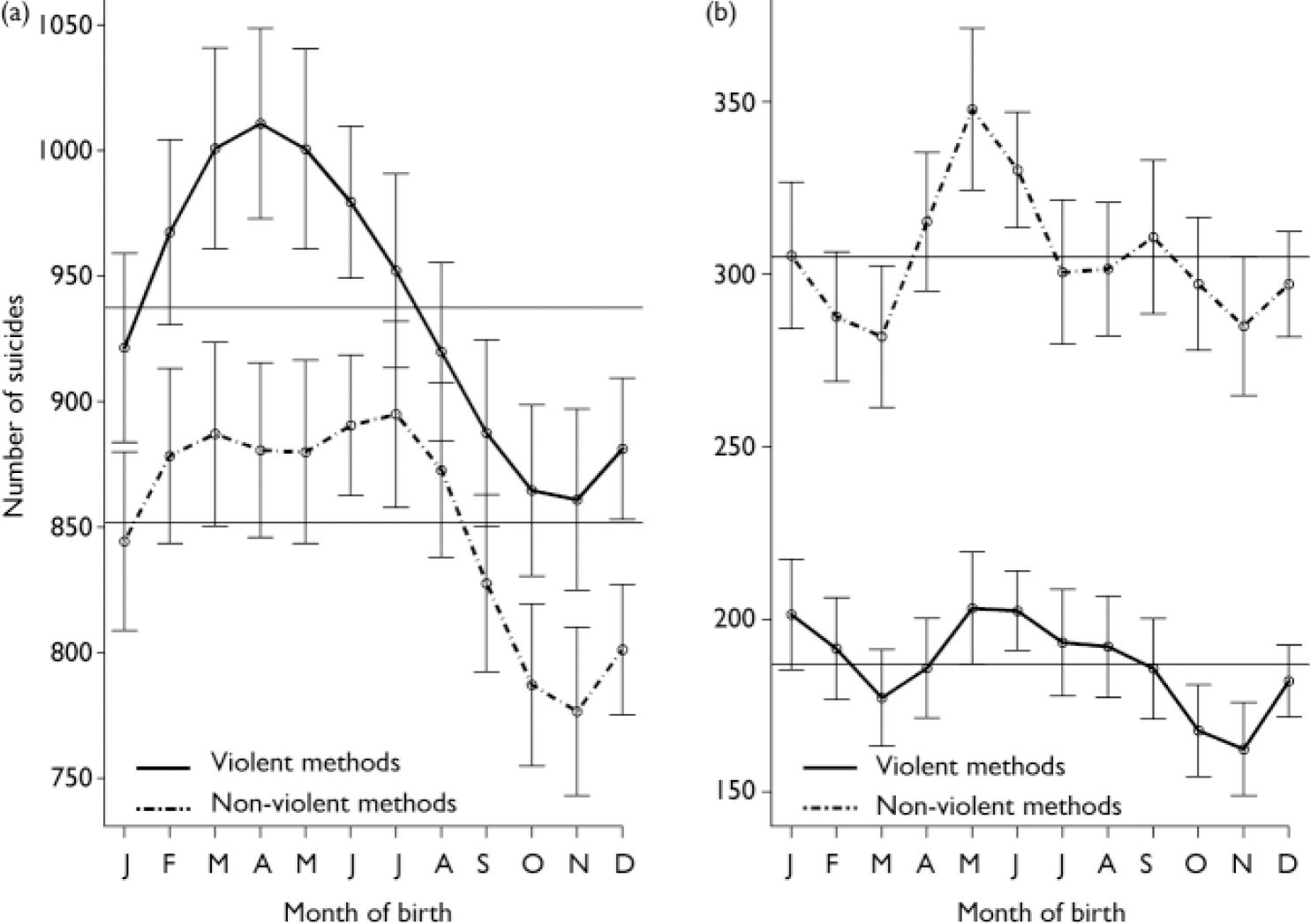

Table 2 shows the frequencies of suicides categorised by method of suicide, gender and month of birth; it excludes 29 cases for which month of birth was not known. Men's suicides involved violent methods significantly more frequently than women's (52.4% v. 38%, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the mean ages at suicide by gender. Since overdispersion was not significant, we fitted Poisson GLMs to explain the variation of suicide counts by month of birth (using the same seasonal components and model selection strategy as in the previous sections), gender, method of suicide (violent and non-violent) and their interactions. In this analysis we considered only the 26 886 suicides with known month of birth. The optimal model has 17 parameters (see Appendix 3 in the data supplement to the online version of this paper) and its predicted detrended values are shown in Fig. 5. It includes significant terms for an overall 12-month cycle of month of birth (P < 0.0001) and significant terms for differences by gender and method and their interaction (P < 0.0001 in all cases). There is also a significant interaction term between gender and a 4-month cycle by month of birth (P=0.011), which establishes the differences in the shape of the seasonal components in cases of female suicide in a way similar to the one described in Fig. 4, and a 3-way interaction among gender, method and a 6-month seasonal term (P=0.028), corresponding to significant differences in the seasonal patterns of month of birth by method in suicides by women. For suicides by men, the monthly birth rate peaks were in spring for violent methods and in summer for non-violent methods; the troughs for both methods occurred in autumn. For suicides by women, the peaks were in late spring and the troughs were in autumn for both methods.

Fig. 5 Predicted detrended values by method in (a) men and (b) women.

Table 2 Frequencies of suicides by month of birth, method of suicide and gender of people born between 1955 and 1966 who died by suicide 1979–2001

| Month of birth | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Deaths by violent methods, n | ||||||||||||

| Male | 919 | 857 | 1041 | 930 | 1044 | 890 | 963 | 953 | 842 | 858 | 859 | 890 |

| Female | 213 | 178 | 173 | 190 | 198 | 202 | 198 | 177 | 171 | 166 | 159 | 179 |

| Deaths by on-violent methods, n | ||||||||||||

| Male | 855 | 782 | 898 | 847 | 925 | 849 | 909 | 880 | 782 | 803 | 709 | 800 |

| Female | 314 | 257 | 281 | 303 | 337 | 313 | 292 | 312 | 305 | 308 | 283 | 292 |

DISCUSSION

Limitations of the study

One of the main problems associated with using routinely collected data, no matter how reliable and complete, is misclassification of data. Also, it must be emphasised that it is impossible to rule out entirely the effect of random fluctuations in birth rates of people who die by suicide, or other influences that might explain the findings. Other limitations of this study include the following.

-

(a) The collected suicide data came from England and Wales, and may not be representative of populations from other countries in the northern hemisphere.

-

(b) There was no information regarding country of birth in the suicide cases that might have confounded the findings; e.g. individuals born in the southern hemisphere who died by suicide in England and Wales might be expected to have seasonal patterns by month of birth similar to those discussed here, but with a 6-month shift.

-

(c) Records of weather parameters such as daily sunshine hours and temperature were unavailable for the birth months of the suicide group.

-

(d) Age-prevalence effect was not adjusted for during the analysis.

-

(e) Data did not include people who were born between 1955 and 1966 but died by suicide after 2001, or those who might do so thereafter.

Interpretation of the findings

The effect of season of birth on suicide can be interpreted, on lines similar to those used by Bradbury & Miller (Reference Bradbury and Miller1985), as a tendency for individuals who later die by suicide to be born during certain months or seasons of the year, in numbers disproportionate to those from the population at large. Given the multifaceted aetiology of suicide it is important to study the phenomenon of seasonality of birth in those who die in this way as this may help to give directions to future research. The large size of the database used in this study, which greatly exceeds that of all previous studies of this subject, enhances its power and its inferential value. The database allows us to establish the presence of significant seasonal patterns, adjusting in comparison with a large control population. The interaction terms of our models correspond to joint variation of two or more variables and allow us to establish the differences of seasonal patterns of month of birth between suicide cases and the control population, adjusting for year of birth; suicide cases and the control population by gender, adjusting for year of birth; and suicide method and gender in suicide cases.

Our results support the hypotheses that there is a seasonal effect in the monthly birth rates of people who kill themselves and that there is a disproportionate excess of such people born between late spring and midsummer compared with the other months. This applied to suicide as a whole and regardless of the methods used, contrary to the findings of previous studies (Reference Chotai and AsbergChotai & Asberg, 1999; Reference SalibSalib, 2002). Our findings are consistent with the reported higher birth rates in spring and early summer of people with affective disorders and alcoholism (Reference Castrogiovanni, Iapichino and PacchierottiCastrogiovanni et al, 1998), whose deaths by suicide represent about 10% of total expected annual suicides in England and Wales, according to the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (Department of Health, 1999). However, the study findings, and without taking into account other risk factors, do not appear in keeping with the fact that people with schizophrenia, who represent about 5% of total annual suicides in Britain (Department of Health, 1999), have a well-recognised winter birth association (Reference Bradbury and MillerBradbury & Miller, 1985; Reference Castrogiovanni, Iapichino and PacchierottiCastrogiovanni et al, 1998; Reference Mortensen, Pedersen and WestergaardMortensen et al, 1999). It may be plausible to assume that the small increase in birth rates of some suicide cases noted in December and January (see Fig. 3), particularly in female cases (see Fig. 4), might be related to the suicide of people with schizophrenia born in winter. Perhaps this could be explored in future research of this area.

Biological assumption of suicidal behaviour

Lester (Reference Lester1995) and Asberg (Reference Asberg1997) reported low levels in cerebrospinal fluid and urine of monoamine metabolites 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), homovanillic acid (HVA) and methyl-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) in suicidal behaviour, impulsivity and depression. Low levels of 5-HIAA in cerebrospinal fluid have been reported in people exhibiting violent suicidal behaviour, such as hanging, stabbing, using firearms or jumping from heights, and impulsivity (Reference AsbergAsberg, 1997; Reference Mann and MaloneMann & Malone, 1997), as well as in patients with an increased risk of a future suicide or suicide attempt (Reference Nordstrom, Samuelsson and AsbergNordstrom et al, 1994). Low levels of 5-HIAA have also been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed patients with high-lethality or well-planned suicide attempts, compared with other suicide attempts (Reference Nordstrom, Samuelsson and AsbergNordstrom et al, 1994). Chotai & Asberg (Reference Chotai and Asberg1999) reported some significant season-of-birth variations in 5-HIAA and HVA levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of a sample of drug-free patients, adjusted for gender, age, height and diagnostic category. Persons born during the winter and spring months, February to April, had significantly lower values of 5-HIAA. The values of HVA as well as the ratios of HVA/5HIAA and HVA/MHPG were significantly higher for those born during the winter months October to January compared with others. However, winter variations in serotonin reported by Chotai et al (Reference Chotai, Salander and Jacobsson1999) are inconsistent with the findings of this study, essentially the opposite of the Swedish findings.

The biological assumption is possible because factors that may influence the brain growth process after a few months of gestation could affect the sensorimotor, cognitive, affective and behavioural development. It has been suggested that annual rhythm in peripheral and central serotonergic turnover, as well as in l-tryptophan and cortisol, which are observed in normal and depressed people, are related to annual rhythm in suicide (Reference Maes, De Meyer and ThompsonMaes et al, 1994; Reference Petridou, Papadopulos and FrangakisPetridou et al, 2002). Seasonal biological rhythm, as in serotonergic activity, may be synchronised by seasonal variations in weather conditions (Reference Maes, De Meyer and ThompsonMaes et al, 1994; Reference Salib and GraySalib & Gray, 1997). A positive relationship between relative risk of suicide during the peak month of suicide incidence and the same-month average sunshine duration has been reported by Petridou et al (Reference Petridou, Papadopulos and Frangakis2002). Melatonin, the secretion of which is suppressed by sunshine, does not appear to have been investigated as a possible contributory factor in relation to suicide.

Seasonality of suicide, whether in relation to the birth or the death of those who kill themselves and the apparent correlation with some weather parameters (Reference Maes, De Meyer and ThompsonMaes et al, 1994; Reference Salib and GraySalib & Gray, 1997; Reference SalibSalib, 2002), is a striking epidemiological characteristic of this phenomenon, which ought to be explored further as it could have some preventive implications. The high degree of sensitivity of the central nervous system to environmental exposures in utero and during infancy (Reference Brenner, Linet and ShapiroBrenner et al, 2004) and the long latency from initiation to clinical onset of many neurological diseases (Reference Torrey, Miller and RawlingsTorrey et al, 2000) and several psychiatric disorders (Reference Castrogiovanni, Iapichino and PacchierottiCastrogiovanni et al, 1998) – including suicidal behaviour, as our study has shown – may raise the possibility that seasonally varying exposures acting very early in life might influence the risk in adulthood. The list of candidate exposures includes not only infections, many of which vary seasonally, but also maternal diet, environmental toxins, photoperiod, temperature, weather and hormonal milieu (Reference Brenner, Linet and ShapiroBrenner et al, 2004).

The ‘month of birth’ factor in suicide can be interpreted in terms of the foetal origins hypothesis (Reference BarkerBarker, 1998) and the maternal–foetal origins hypothesis (Reference O'Keane and ScottO'Keane & Scott, 2005). The foetal origins origins hypothesis suggests that exposure of the foetus to an adverse environment in utero leads to permanent programming of tissue functions and subsequent risk of diseases. One system implicated in the putative altered programming in utero is the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Reference O'Keane and ScottO'Keane & Scott, 2005).

On the basis of the foetal origins hypothesis, it may be plausible to suggest that the ‘month of birth’ factor in suicide may reflect the timing of an errant early neural migration or differentiation process due to one or more of these exposures, resulting in subtle histochemical abnormalities underlying the individual's constitutional vulnerability and affective predisposition. This could act as a latent risk factor that might enhance other suicide risk factors in some predisposed individuals. This assumption gives some hope that developmental approaches might improve our understanding of the psychopathology of depression and suicidal behaviour and could offer new strategies for treatment and prevention.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ There is a 17% increased risk of suicide for people born in the spring and early summer compared with those born in autumn: this risk increase is larger in women (29.6%) than in men (13.7%).

-

▪ The size of the database used in this study provides a powerful opportunity to assess the birth birth–death association in suicide, with nearly 27 000 suicides – far more than in all previous studies.

-

▪ Biological assumption of suicidal behaviour could have implications for our understanding of the psychopathology of suicide and eventually could offer new strategies for treatment and prevention.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ It is impossible to rule out entirely the effect of chance fluctuations or other influences that might explain the findings.

-

▪ Misclassification might have occurred in routinely collected data.

-

▪ The collected suicide data came from England and Wales and may not be representative of the populations of other countries in the northern hemisphere.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emma, Mark and Michael Salib, Jean Moxey and Judith Eden, Judith Eden, Peasley Peasley Cross Hospital, Sheila Cawley, Bernie Hayes, Kate Spencer and Emma Jones, Hollins Park Hospital, for their help in preparing this paper. Our thanks also to the Office for National Statistics for supplying the mortality data.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.