INTRODUCTION

In 2014, Brazilian politics was shaken up by the lava jato (LJ) operation, a law-centered anticorruption initiative. LJ unveiled a large corruption scheme in Brazil's national oil company, Petrobras, which involved directors, political party officials, and large construction companies. LJ was both disruptive and contentious. To some, it started a new chapter in Brazil, with greater respect for the rule of law and a collective state of mind concerned with ending impunity and building integrity in politics and business (Reference Bullock and StephensonBullock & Stephenson, 2020). To others, it undermined democracy and the rule of law, paving the way for an autocratic leader—Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2019; Reference Bello, Capela and KellerBello et al., 2020; Reference Carvalho and PalmaCarvalho & Palma, 2020; Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a; Reference EvansEvans, 2018; Reference MészárosMészáros, 2020).

This article illuminates those discussions by looking at LJ as a site of legal consciousness production. Empirically, it focuses on conversations involving LJ prosecutors on Facebook from 2017 to 2019. Considering this body of data, the article addresses the question: “When prosecutors and the people talked about LJ, what did they talk about?” My findings support skeptical views of LJ. The exchanges between LJ prosecutors and Facebook users coproduced a cultural schema averse to the rule of law. Anticorruption work was glorified, construed as messianic or patriotic, not as an institutional endeavor based on, and subject to, rules. Society was called to participate in a fight against corruption that became a crusade against institutions, with systematic attacks on Congress and the Supreme Court (STF). This schema supported people's mobilization both online and offline, and it possibly legitimized Bolsonaro's autocratic moves.

These findings have implications for both legal consciousness and anticorruption research. Regarding legal consciousness scholarship, I add to a promising line of inquiry designed to capture the interactive processes through which shared cultural schemata on law are produced and deployed, which scholars are conceptualizing as “relational legal consciousness” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019). In this vein, I argue for the analytical incorporation of social media platforms into the social space where the rule of law is re- or deconstructed and for posts/comments as valid data sources in legal consciousness studies. I also argue for integrating issues of identity, mobilization, and hegemony; and for greater nuance in legal consciousness studies of resistance (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey, 1998, Reference Ewick and Silbey2003). Regarding anticorruption scholarship, I call for works that take culture more seriously and focus on how consciousness and ideology contribute to the production—or destruction—of integrity in political institutions and elsewhere.

The article has five parts. Section 2 gives an overview of LJ. Section 3 situates the article theoretically. Section 4 describes the data and analytical procedures. Section 5 presents the findings. Section 6 discusses the findings and lays out conclusions.

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF, AND A NEW LOOK AT LJ

LJ started as an ordinary money-laundering investigation. The federal police arrested Brazilian financier Alberto Youssef and two associates. (They sited their activities next to a car wash, hence the operation's nickname.) Brazilian police officers knew Youssef. More than a decade before LJ, he was caught sending money abroad for politicians and businessmen in another high-profile case struck down by higher courts, the Banestado scandal. This time, the police found suspicious ties between Youssef and a former Petrobras director, Paulo Roberto Costa. Youssef's email indicated that he had purchased a SUV vehicle as a gift for Costa. Costa was arrested, revealing a bigger corruption scheme at Petrobras including frauds in Petrobras contracts that benefited a cartel of construction companies, which, in turn, paid bribes and kickbacks to Petrobras officials, politicians, and political parties. Costa received his SUV from those payments (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a; Reference MoroMoro, 2018).

The discovery of the Petrobras scheme changed LJ's scope and significance. The CEOs of the largest Brazilian construction companies were dragged into the operation, most notably Odebrecht, a conglomerate that had expanded aggressively worldwide. Many CEOs were arrested and accused of corruption, money laundering, and criminal activity.Footnote 1 Equally remarkable were LJ's effects on politics. Key politicians and party officials were indicted, and all subsequent major political events became entangled with the operation. In 2014 Dilma Rousseff—the sitting president and Workers' Party (PT) affiliate—was narrowly reelected. The electoral process was highly polarized, corruption being central in the debates and campaign. In 2015, Rousseff faced mass protests—again, largely over corruption—and in 2016 she was impeached. In 2017, former president Lula da Silva—an icon in the Brazilian left and PT—was convicted of corruption and money laundering under LJ. In 2018, Lula was arrested and barred from running for the presidency, a contest he was leading. With Lula off the ballot, the winner was Bolsonaro, a former army captain and far-right politician who favored military dictatorship and made outrageous remarks against women, Black people, and LGBTQ people (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a).

LJ had consequences beyond Brazil. Politicians from African, Central American, and South American countries were implicated.Footnote 2 It also fell under US jurisdiction, leading to plea agreements between Brazilian companies like Odebrecht and Petrobras and US authorities involving billions of dollars in bribes.Footnote 3 Eventually, LJ became known as the largest corruption scheme of all time,Footnote 4 much larger than Watergate.

For most of its lifetime, LJ and those behind it were revered by media outlets, academics, and organizations in Brazil and abroad. Sergio Moro—the judge who presided over the main LJ cases—and the prosecutorial task force led by the young federal prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol were treated as champions against corruption and in promoting the rule of law, receiving many awards and honors (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a). Yet over time, its methods, outcomes, and legacy became more controversial. Moro and the prosecutors were accused of undue interference in Brazilian politics and of bias against the left and the PT (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2019; Reference Bello, Capela and KellerBello et al., 2020; Reference EvansEvans, 2018; Reference MészárosMészáros, 2020). Two events threw fuel on this bonfire. In 2018, after the elections, Moro became Bolsonaro's Justice Minister.Footnote 5 In 2019 the news outlet Intercept Brasil published a series of leaked messages between Moro and the LJ prosecutors in what was dubbed the vaza jato scandal.Footnote 6 These messages—and others that came laterFootnote 7—exposed controversial practices by Moro and task force members, including in the lawsuits against Lula.

About a year after Bolsonaro's election, LJ lost momentum and is reportedly dead.Footnote 8 As soon as he took office, Bolsonaro appointed a new chief federal prosecutor, Augusto Aras. Aras deemed prosecutorial task forces like LJ inefficient and proposed to create an anticorruption unit, linked to his office, to carry out investigations. Bolsonaro also attacked the independence of agencies crucial to LJ's success, including the national financial intelligence unit COAF. In April 2020, Moro resigned from Bolsonaro's cabinet, alleging that the president was interfering with the federal police to protect his sons from investigation. In February 2021, the LJ task force was officially dissolved, ironically, on the same day Arthur Lira, who had been implicated in LJ, was elected Speaker of the House—with support from Bolsonaro.

While the intentions and partisanship of LJ agents merit scrutiny, the operation presents other features that have received less scholarly attention. LJ was not a civil society campaign based on naming and shaming; nor was it a bureaucratic undertaking based on active transparency and technology. It was an operation by lawyers in the name of the law through fundamentally legal means. At the same time, LJ had a distinctive public profile. As the legal agents behind the operation recognize, it was strategically designed as a multi-phased undertaking.Footnote 9 Repeatedly, investigators conducted phases of searches, seizures, and arrest orders. These operations, which had catchy nicknames, kept the public's attention and made the case evolve like a TV series—if not a Brazilian soap opera (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a).

In addition, the findings on LJ received extensive publicity. The Public Prosecutor's Office launched a website detailing its work on the operation and providing case documents. After each LJ phase, prosecutors and investigators held press conferences to explain the measures being taken and how they fitted into the operation. Simultaneously, Moro released court documents to the media, feeding the Brazilian populace with a massive amount of information, such as affidavits, bank statements, and videotaped depositions (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a). A public conversation about law, justice, corruption, and politics was launched, and given the ubiquitous presence of smartphones in Brazil,Footnote 10 it spilled over to social media, where it reached virtually all Brazilians.Footnote 11 LJ prosecutors actively participated in this process, using—and thus popularizing—the hashtag #lavajato to disseminate materials and statements on the investigation.Footnote 12

Considering LJ as a high salience process in which agents of the law established intense communication with the Brazilian public, we can envision promising research approaches to examine the operation. In this article, I draw from cultural studies of corruption and, particularly, from recent developments in legal consciousness scholarship, to devise one such approach.

FROM ANTICORRUPTION TO RELATIONAL LEGAL CONSCIOUSNESS: THE THEORETICAL REALMS AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF THIS STUDY

Over the last few decades, academic works on corruption have proliferated. Many earlier studies treated corruption as a “Third-World” affair, reflecting assumptions from modernization theory that corruption (or lack thereof) correlated to stages of political underdevelopment (Reference HuntingtonHuntington, 1968; Reference KlitgaardKlitgaard, 1988; Reference NyeNye, 1967). Studies also typically deployed a rational choice framework to estimate the causes and consequences of corruption. The causes were often understood as a principal–agent problem. Corrupt individuals were seen as agents tasked with acting for the public good but who also engaged in rent seeking (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 1982; Reference KlitgaardKlitgaard, 1988; Reference Rose-AckermanRose-Ackerman, 1978). Scholars thus focused on the incentive structures that could lead agents to behave in this way (Reference Rose-AckermanRose-Ackerman, 1978, Reference Rose-Ackerman1999).

This rational choice framework remained influential as an anticorruption industry was established in the international development domain, gathering international organizations, consultants, think tanks, academics, and policy entrepreneurs to design policy solutions that would make countries and businesses more resilient to corruption (Reference SampsonSampson, 2010). These solutions also drew from assumptions that changes in incentive structures, often pursued through reforms in laws and law enforcement organizations, could change individual and collective behavior. With the rise of this anticorruption industry, the scope of corruption and anticorruption studies was also transformed. Corruption became defined as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” and empirically equated to bribery (Reference DavisDavis, 2019; Reference WedelWedel, 2012). The studies focused on government organizations and public officials rather than businesses and other non-state actors (Reference HoughHough, 2013; Reference SampsonSampson, 2010; Reference WedelWedel, 2012).

Anthropologists, sociologists, and other social scientists came later and remained relatively marginal in corruption studies and the anticorruption industry. However, these scholars challenged the reigning rational choice approach, for example, by analyzing culture. The deconstructive potential of cultural studies of corruption and anticorruption was twofold. First, scholars demonstrated that the mainstream definition of corruption was not universally shared. In certain countries and communities, bribery was not only pervasive, but also culturally accepted and socially expected (Reference HastyHasty, 2005; Reference Lomnitz and DaltonLomnitz, 1971; Reference WedelWedel, 1986; Reference YangYang, 1989). Second, scholars demonstrated that oftentimes, measures globally promoted as solutions to corruption made no sense where they were being implemented and sometimes made countries worse off than before (Reference KennyKenny, 2017; Reference Mungiu-PippidiMungiu-Pippidi, 2006; Reference Sampson, de Sousa, Larmour and HindessSampson, 2008).

Though these studies exposed the clashes between anticorruption efforts and local cultural contexts, the role of anticorruption initiatives and agents as producers of culture received far less attention. Initiatives and agents often generate frames and symbols that may influence how ordinary people perceive and respond to corruption, politics, and institutions. Corruption scholars are beginning to unpack these processes by focusing on political behavior. Studies in this vein, in countries from Indonesia to Costa Rica to Nigeria (Reference Cheeseman and PeifferCheeseman & Peiffer, 2020a; Reference Cheeseman and PeifferCheeseman & Peiffer, 2020b; Reference Corbacho, Gingerich, Oliveros and Ruiz-VegaCorbacho et al., 2016; Reference Köbis, Troost, Brandt and SoraperraKöbis et al., 2019; Reference PeifferPeiffer, 2018), have demonstrated that systematic exposure to anticorruption messages may result in apathy rather than activism—people feel that their polities and communities are so engulfed in the problem that nothing can be done. Sometimes, individuals even engage in corrupt behaviors such as paying bribes.

Analysts have not completely ignored the role of LJ in cultural (re)production. Reference Bullock and StephensonBullock and Stephenson (2020) posit that LJ “signifies an attitude or state of mind—one that refuses to accept the impunity of the wealthy as an immutable fact of life.” They consider that “at its best, (this) ‘Lava Jato Spirit’—the belief that systemic corruption is not inevitable and need not to be tolerated—represents a potentially transformative cultural shift in Brazil.” Given LJ's legalistic character, this proposition feeds long-standing hopes that law and lawyers could modernize society, promoting liberal values like respect for the rule of law (Reference GarthGarth, 2014; Reference GordonGordon, 2010; Reference Halliday, Karpik and FeeleyHalliday et al., 2007, Reference Halliday, Karpik and Feeley2012; Reference Tyler and DarleyTyler & Darley, 2000). Of course, this is disputed. Other authors who examine the discourses advanced by media outlets and LJ legal officers during the operation argue that the messages were of different kinds, construing corruption as a left-wing problem (Reference Bello, Capela and KellerBello et al., 2020; Reference DamgaardDamgaard, 2019) or supporting illiberal ideas that became central to Bolsonaro's rise and rule (Reference Carvalho and PalmaCarvalho & Palma, 2020; Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a).

These studies have clear limitations, nonetheless. They focus on frames that circulate and are transmitted to the public but not on these frames' production. Moreover, when looking at frames' transmission, they focus on elite agents (LJ legal officers and mainstream media), ignoring how transmission resonates with the public. This is a sizeable gap, as much of LJ's life involved interactions between legal agents and ordinary people, thanks to the formers' emphasis on publicity and social media. What exchanges happened in this shared space? What changes and continuities in cultural schemata did those exchanges promote? What do emerging schemata support—more integrity in politics and business and an enhanced rule of law, or something less positive? What does this all reveal about not just LJ and corruption control, but also how people have come to shape—and be shaped by—legality in the digital age?

Here is where recent developments in legal consciousness scholarship become useful. Legal consciousness scholars drew from the cultural or interpretive turn in the social sciences to revolutionize law and society studies. Central to this was an emphasis on “a Weberian conception of social action … including analyses of the meaning and interpretive communication of social transactions” (Reference SilbeySilbey, 2005 p. 326). Scholars looked at what law represented to people—that is, what meaning(s) people gave to law in their daily lives and what using or not using law signified to them. Those scholars' ambition was to theorize about the cultural foundations of law's hegemony.Footnote 13 They asked how ordinary people (re)produce cultural schemata that, in turn, support the enduring structure of the rule of law (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey, 1998). A vast sea of studies followed covering many issues, including women being sexually harassed on the streets (Reference NielsenNielsen, 2000) and at work (Reference Blackstone, Uggen and McLaughlinBlackstone et al., 2009; Reference MarshallMarshall, 2017), women and minorities facing job discrimination (Reference Albiston, Fleury-Steiner and NielsenAlbiston, 2006; Reference Hirsh and LyonsHirsh & Lyons, 2010), poor people seeking welfare rights (Reference CowanCowan, 2004; Reference MerryMerry, 1990; Reference SaratSarat, 1990), undocumented immigrants deciding whether to file claims (Reference AbregoAbrego, 2011), sex workers dealing with abuses (Reference BoittinBoittin, 2013), and family members of brain-injured patients facing decisions about life (Reference Halliday, Kitzinger and KitzingerHalliday et al., 2015). Many of these studies highlight the role of social forces like gender, race, and class in shaping how subjects experience and make sense of law and legal recourse while facing harassment and discrimination, building bridges with critical race theory and legal feminism. A few chart instances where movements and minorities use informal venues outside courts to seek justice (Reference RaeRae, 2019), including the internet (Reference Gash and HardingGash & Harding, 2018).

Reference SilbeySilbey (2005) criticized legal consciousness scholars for (1) tracking variations in people's thoughts and attitudes while ignoring their underlying material conditions and (2) abandoning the ambition to use these thoughts and attitudes as windows to theorize about how law's hegemony is sustained. Silbey claimed that legal consciousness scholarship had “lost the social” and that maybe the concept should be abandoned. Legal consciousness scholarship continued to grow, nonetheless. Some scholars continued to investigate the cultural foundations of law's hegemony; others noticed that the concept had already proven useful to other critical endeavors.

Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel (2019) identified three schools of legal consciousness research, that is, three ways in which legal consciousness scholars shed critical light on the law–society interplay. Silbey's study of how ordinary people support law's power fits a hegemony school, but the concept also supported a mobilization school, which focuses on how understandings of rights may support transformative action by marginalized groups, and an identity school, which focuses on how “legal consciousness and identity emerge from and shape one another” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019 pp. 337–38). In addition, Chua and Engel notice the emergence of relational legal consciousness as a promising pathway for researchers to follow. This recognizes that the meanings people give to law in their daily lives develop amid social interactions and that both the meanings and the interactions can be coproduced. Authors consider that this coproduction can happen to different degrees and, indeed, speak of a relational legal consciousness continuum. At one end of the continuum are studies that “regard the individual mind as the locus of legal consciousness” deeming “other persons or social forces independent variables in relation to individual worldviews, perceptions, and decisions” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019 p. 346). In the middle are studies that “retain the individual as the appropriate object of study but treat other individuals as cocreators of consciousness rather than mere external variables” (347). At the other end are studies that “reject the individual as the unit of analysis and (view) legal consciousness as a fully collaborative phenomenon” in which “individual subjectivity (fades) completely into relationships” (347–348).

These research avenues (Table 1) seem very suitable for studies on social media platforms, where parties interact and become cocreators of legal consciousness. These studies are, furthermore, absolutely needed. As the Cambridge Analytica scandal tragically revealed, there is growing integration between social media and everyday life. Social media platforms store and disseminate frames and templates with which people make sense of life events and processes. The topic, however, is remarkably absent from scholarship. Considering the communication between the LJ legal agents and the public on Facebook, this article fills in that gap and expands relational legal consciousness research on both ontological and methodological fronts. Ontologically, I demonstrate that the rise of social media platforms has radically altered the space in which social interactions occur and the law–society interplay unfolds. For example, these platforms offer a chance for unprecedented encounters between law agents and ordinary people where the meanings of law can be (re)negotiated with effects in real life. Unless the use of social media de-escalates severely in society, this will be of absolute importance to keep track of. Methodologically, I demonstrate that posts/comments are valuable data sources on how sociolegal transactions take shape and evolve. Most legal consciousness research—including relational research—is qualitative, using in-depth interviews. Recent works have argued for the need to broaden this spectrum. Reference St-PierreSt-Pierre (2019) suggests using legal documents as entry points to study elite lawyers' legal consciousness, claiming that they are “repositories of meanings that elite lawyers presume, construct, distort, diffuse, and systematize both within and beyond the realm of the legal profession” (Reference St-PierreSt-Pierre, 2019 p. 333). She adds that such powerful actors can be “unreachable or reluctant” to be interviewed; hence their documents are a valid substitute for qualitative interviews or observations. Moreover, documents can “provide a more precise understanding of lawyers' success in constructing technical legal meanings and in framing issues” (Reference St-PierreSt-Pierre, 2019 p. 334). With research that takes social media seriously as a site of relational legal consciousness production, a similar expansion in data sources is in order. Scholars must incorporate textual posts, comments, videos, memes, emojis, and similar repositories of meanings typical of social media urgently, this work being an initial step in such direction.

Table 1. Research avenues on relational legal consciousness (based on Chua & Engel, Reference Chua and Engel2019)

DATA AND METHODS

Research for this article started in early 2019 with attempts to collect data on posts/comments about LJ on Facebook. I chose Facebook because its use is more widespread in Brazil than Twitter, whose user base tends to be more elite, and on Facebook—contrary to WhatsApp—posts/comments are largely public. Facebook posts/comments do not, of course, perfectly represent the entire social media landscape, and caution is necessary when extrapolating findings from research in that platform. There is, nonetheless, a growing integration among platforms, so that content from Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram can be shared through WhatsApp and vice versa, and it takes only a few users to do this for the content to go viral across platforms. Focusing on Facebook posts/comments posed some obstacles to my data collection. Because of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Facebook was closing access to data on its posts and users by third-party applications. Using a social media-monitoring tool and web-scraping techniques,Footnote 14 I nevertheless located and extracted initial data for all the posts on public Facebook pages that included the words lava and jato. The data included the posts' URLs and dates, content excerpts, and information on their performance: how many times they had been liked, shared, or reacted to,Footnote 15 and how much engagement they had generated.Footnote 16

Though it would have been ideal to study LJ's social media trajectory since 2014, my monitoring tool could only go back through the last 2 years of Facebook page feeds. My dataset thus contained only entries for fall 2017–fall 2019. However, 2017–2019 was sufficiently eventful for my dataset to be analytically interesting. This timeframe involves Lula's arrest and conviction, the Brazilian presidential elections won by Bolsonaro, Moro's appointment to Bolsonaro's cabinet, and the vaza jato scandal. Throughout these events, many conversations happened on social media, as they did on Brazilian street corners.

My initial dataset had over 220,000 posts. With research assistants, I reviewed and cleaned it up. We removed entries referring to LJ in Peru,Footnote 17 some duplicated entries, and entries with no comments. This left us with about 75,000 posts. We then extracted the comments for these posts using exportcomments.com. At this stage, I focused on the top 1% of posts (750 posts), considering metrics of engagement. Because some posts were being deleted—there is some “mortality” in social media data entries—I ended up with data for 756 posts. My final dataset contained full information on these posts—their URLs, dates, content (textual or otherwise; videos and images were manually downloaded and stored for analysis), pages of origin, number of likes/reactions, and engagement scores. It also contained their respective comments, summing up almost 3 million chunks of text, memes, and images. Graph 1 provides the frequency distribution of these posts/comments and their relevant background events.

GRAPH 1 Frequency distribution for the highest-engaging posts with the terms lava and jato and the comments on these posts (Oct 2017–Oct 2019). Relevant events in this timeframe: (1) Lula's arrest; (2) Bolsonaro's election, Moro's appointment to cabinet, supreme court discussion on pardon decree issued by former president Temer—Who replaced Rousseff and ruled from 2016–2018 (more information below); (3) first few months of Moro in Bolsonaro's cabinet, Lula's second conviction, Temer's brief arrest in LJ, supreme court discussion on whether some LJ cases should be tried by electoral courts, controversies over the handling of funds recovered by LJ prosecutors; (4) Vaza jato scandal

In this research, I was more interested in the production of legal consciousness driven by, or with participation of, legal agents—that is, legal consciousness produced through the (virtual) interaction between these agents and the public at large. Hence, my analysis emphasized posts by LJ prosecutors Deltan Dallagnol (n = 53) and Carlos Lima (n = 1). These totaled 54 posts and 122,335 comments. Graph 2 provides the frequency distribution of these posts/comments and their relevant background events.

GRAPH 2 Frequency distribution for the high-engaging posts by Dallagnol and Lima and the comments on these posts (Oct 2017–Oct 2019). Relevant events/topics driving discussions in this timeframe: (1) Bolsonaro's election, Moro's appointment to the cabinet, and supreme court discussion on pardon decree issued by former president Temer—Who replaced Rousseff and ruled from 2016 to 2018 (more information below); (2) Temer's brief arrest in LJ, supreme court discussion on whether some LJ cases should be tried by electoral courts; (3) Vaza jato scandal

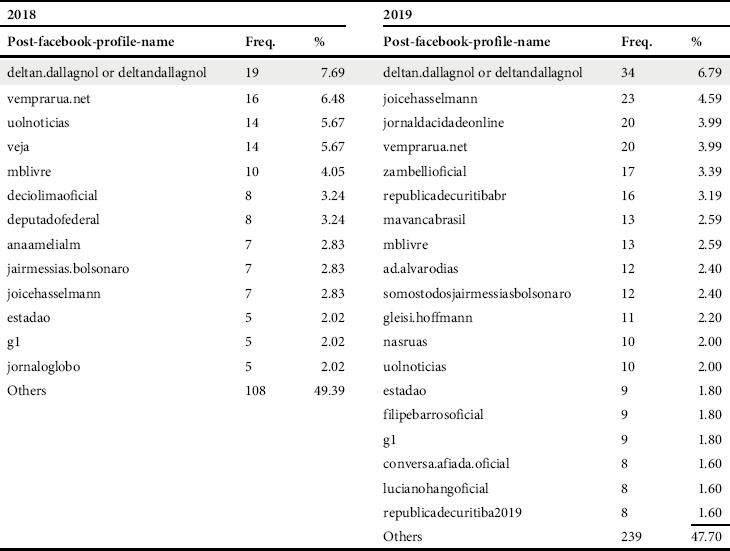

My emphasis on prosecutors and Dallagnol's outstanding presence in my sample—making this an almost “one-man” study—raise important theoretical and methodological questions. Facebook conversations on LJ certainly happened beyond the prosecutors' and Dallagnol's pages, where competing narratives about the operation could be crafted. In my 756-post dataset, 181 pages were represented, including some by high-profile PT figures (e.g., Gleisi Hoffmann, the chair of PT, and Lula da Silva) and other critics of the operation (e.g., Conversa Afiada, a news website by journalist Paulo Henrique Amorim). However, these pages had far less reach and engagement than Dallagnol's. Dallagnol's page was the most influential on this matter in the data (Graph 3) in both 2018 and 2019 (Table 2). Lula and other PT members hold far more marginal positions in these rankings.

GRAPH 3 Top 10% (18 out 181) of the Facebook pages with the most-engaging posts on lava Jato from Oct 2017 to Oct 2019. Dallagnol also used a page with the ID deltandallagnol; computing both IDs, his score in this graph adds to 53

Table 2. Pages most represented in the top-756 Facebook posts with the terms “lava” and “jato” from Jan 2018 to Oct 2019

The decision to examine the prosecutors' and Dallagnol's posts is, therefore, justified by their relevance and the fact that these agents are generally driving the conversation around the operation in the Brazilian social media landscape in my data. Moreover, the posts by LJ prosecutors and Dallagnol represent a unique space where citizens and law agents could interact and give meaning to corruption, anticorruption, and the rule of law. Examining what happens in this space is vital. What did the prosecutors say, and what responses did they get? How do posts/comments come together to form coproduced schemata, what were such schemata about, and what effects could they have on support to the rule of law, online and offline? Answering these questions lets us test whether LJ helped to produce a culture of integrity and respect for the law—and, if not, to understand what it did to Brazilian legal/political culture.

Within the social sciences, there has been a substantial growth in qualitative and mixed-methods studies using social media data. Reference SnelsonSnelson (2016) shows that content analysis is the most common approach. Content analysis can be qualitative, quantitative, or both. Quantitative/qualitative approaches can be deployed in parallel or sequentially, depending on the study objectives. This paper combines both forms of content analysis. On the quantitative front, two steps were taken with support from big data experts—for the whole dataset and month by month. First, frequencies for the most-used words in the comments to posts by Dallagnol and Lima were calculated. Second, networks of words were mapped, which show what words are more connected to one another. The analysis was then deepened with qualitative reading and coding of posts/comments, considering comments that had at least one like and, therefore, some visibility and resonance. This was triangulated with academic and media sources on LJ to contextualize the analyses better.

Research using Facebook posts/comments also raises ethical and legal concerns (Reference Mancosu and VegettiMancosu & Vegetti, 2020; Reference SalganikSalganik, 2019; Reference ZimmerZimmer, 2010). Although what people post/comment on public Facebook pages is accessible to anyone (in contrast to, e.g., private messages or groups), they have not given consent for researchers to use such posts/comments. In Zimmer's words, “just because personal information is made available in some fashion on a social network, does not mean it is fair game for capture and release to all” (2010: 323)—and because social media data are massive, getting consent from those involved is impossible. Moreover, accessing such data can conflict with Facebook's terms of service, which became more stringent after the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Reference Mancosu and VegettiMancosu and Vegetti (2020) argue that accessing and downloading posts/comments from public pages is legally safe and generally tolerated by Facebook, although sometimes the company pushes back against academics. In addition, research using posts/comments clearly is of public and scientific interest. The ethical concerns, nonetheless, remain. A central problem is that authors of the posts/comments are identifiable—readers can visit the posts, compare transcripts with the content of the comments, and determine who those authors are, which could cause them harm (e.g., reputational damage or offline prosecution). Authors recommend taking measures to reduce the risk of user reidentification. In quantitative analyses, this is easier to accomplish, as findings can be reported in aggregate. But researchers “may wish to quote a user's post to provide qualitative evidence, making it possible for third parties to search the user directly on the platform” (Reference Mancosu and VegettiMancosu & Vegetti, 2020 p. 3). In addition, journals may encourage or require that data be shared for reproducibility (Reference Mancosu and VegettiMancosu & Vegetti, 2020), which can put users' identities at risk.Footnote 18 In this article, I use three measures to reduce the risk of reidentification. First, I report on my quantitative analysis in aggregate. Second, while in my qualitative analysis I refer to, and sometimes transcribe, comments, these transcripts are anonymized. Third, when providing context for these comments, I only make general references to the posts, making it more difficult for readers to find them on Dallagnol's feed.Footnote 19

COPRODUCED MEANINGS FOR AGENTS OF THE LAW AND THE FIGHT AGAINST CORRUPTION: ALL THE GLORY TO LJ LEGAL OFFICERS

The frequency of the most-used words in the comments (Graph 4) shows that, through the interactions examined in this article, Facebook users glorified LJ legal officers. Most terms with salience in the dataset celebrate the operation, such as “congratulations (parabéns),” “isupportlavajato (euapoioalavajato),” “support (apoio),” and “strength (força).” The meaning of other terms is at first less certain, but they also have celebratory connotations. For example, users often commended legal agents for the “work” (trabalho) they did in LJ, while “Brazil” (Brasil) and “country” (país) often appear when users are praising legal agents for their patriotism and efforts to change the country. As an illustration, Dallagnol once encouraged his audience to support political candidates who favored anticorruption reforms. One comment statedFootnote 20:

Congratulations Dr. Deltan for your wonderful work, for your efforts and example as a good Brazilian, putting your competence and your patriotism to the benefit of Brazil. … It is Brazilians like you that we need to really change the country. And we will get there, the good Brazilians are the majority.

GRAPH 4 Frequency of most-used words in comments to the Facebook posts by Deltan Dallagnol (n = 53) and Carlos Lima (n = 1) in the top-756 posts with the terms “lava” and “jato” from Oct 2017 to Oct 2019

On another post, Dallagnol rejected the use of his image by political candidates. A user commented:

Today I listened to your always-enlightening words on (radio station). Thank you for your wonderful work, which you undertake with great professionalism and love to our country. Brazil needs many Deltans

![]() .

.

No other term offers evidence of this glorification better than “God (Deus).” This term appears frequently in the sample and, in late 2018, becomes the most frequent term in the comments. Sometimes “God” represents anticorruption efforts as a battle between good and evil. Dallagnol wrote a post claiming that vaza jato had been politically motivated. A user commented:

Deltan, the evil never wins over the good, you will know the truth and the truth will set you free, LJ is not a simple operation, it is liberation from the hands of a criminal organization, which brings hope back to people who had lost trust in the justice, congratulations to all prosecutors, judges, and may God be with you.

On another post, he rejected accusations of abusing his power raised in the vaza jato context. A user wrote:

Brazil is with you. Christ's Church is supporting you with our prayers. God is with you, just like with David who defeated Goliath.

In this context, LJ legal officers are often depicted as God's envoys. On a post where Dallagnol celebrated LJ's success, a user commented:

Congratulations Deltan! you are ANGELS sent by GOD to save us! You are VERY courageous! Protecting people who deserve and others who Do not DESERVE! I keep looking for words to express how much you are BEING our HEROES! … We are in this together! WE LOVE BRAZIL! We will WIN! God is in command!

On another, where Dallagnol was lamenting that LJ was seemingly ending, a user wrote:

We are with you Deltan, we see how much you and your family are sacrificing, and the hardships and restrictions due to your engagement … so know, an entire nation respects and has esteem for you, you are a man of God, a gift from heaven to us!!!!

Much more commonly, however, “God” is used to communicate a wish that God will provide the LJ legal team with strength, protection,Footnote 21 and even reward for their actions. A few examples follow:

Admirable this prosecutor. Determined, brave and competent, just like minister Moro. They are fighting for Brazil, so we can have a country that is respected, disciplined, and prosperous. Congratulations to these tireless Brazilians, God bless them![]() (post where Dallagnol reported on his participation in a public event).

(post where Dallagnol reported on his participation in a public event).

…Be strong, warrior, know that what you did until now certainly will result in betterment for the most oppressed. And God certainly will give you the deserved reward for your effort and dedication to this cause. (same post above).

Congratulations on the professionalism, courage, and persistence in doing your work with dignity!! May God give you force to never desist because we, good Brazilians, are with you Sir!! ![]() (post where Dallagnol was rejecting accusations of bias raised in the vaza jato context).

(post where Dallagnol was rejecting accusations of bias raised in the vaza jato context).

Dallagnol's online activities also feed this glorification of LJ officials. For example, on social media platforms, Dallagnol describes himself as a “disciple of Jesus.”Footnote 22 When the STF was deciding a habeas corpus petition filed by Lula seeking to avoid being imprisoned, he tweetedFootnote 23 that he would be “fasting, praying, and rooting for the country.” On the posts in my dataset, he often appealed to a rhetoric that likened LJ agents to missionariesFootnote 24 or martyrs.Footnote 25

Three observations can be made about these findings. First, they build an image of LJ as a messianic and patriotic endeavor of extraordinary humans or even divine entities, not as an institutional accomplishment. Second, this image gets mobilized to shield the operation from its critics. If anticorruption is a battle between good and evil and the judge and the prosecutor are “angels,” their conduct cannot be doubted. Indeed, once the vaza jato scandal broke out, Dallagnol posted copiously in defense of his conduct in the operation. Some Facebook users reproached him and Moro, writing:

Game over, partner ![]() . Did you understand or do you want me to draw it

. Did you understand or do you want me to draw it ![]() .

.

#Morogate … Nobody is above the law. Neither are you. In a serious country, these audios would lead to the resignation of Moro, the fall of that government and the call for new elections.

But these were outnumbered by others who commented:

There is no need for explanations. We are all with you. You are our hope of a better Brazil. Be strong!!!

Deltan Dallagnol we trust you!!!!! We trust Dr. Sérgio Moro!!!!!!!!! We trust LJ!!!!!! Keep up your work in the benefit of this Country!!!!!!!!

Deltan Dallagnol be strong! The good people are beside you! Brazil needs you to remain firm and strong in this real struggle of light against darkness! May God bless you all and your families.

Last, this cultural construction of LJ legal officers as supernatural individuals or divine entities did not remain restricted to the online world. From street protestsFootnote 26 and magazine covers (Reference Solano, Casara and PucheoSolano, 2018) to carnival paradesFootnote 27 and the fashion industry,Footnote 28 these officers—especially Moro—were portrayed as heroic and/or sacrosanct. Perhaps it was no coincidence that Bolsonaro chose the campaign symbols (the “myth,” ready to fight crime and corruption) and motto (Brazil above everything, God above all) he did. LJ did not create Bolsonaro, but it seemingly laid the cultural foundations that allowed Bolsonarismo to thrive.

COPRODUCED MEANINGS ON THE PEOPLE AND THE FIGHT AGAINST CORRUPTION: THE MAKING OF AN ACTIVE SOCIETY

The exchanges examined in this article also supported the coproduction of meanings on the role and place of society in the fight against corruption. Comments with the word people, which have a high frequency in the data, are at the heart of this and convey two different messages. Sometimes, they refer to a passive, powerless entity, victimized by corruption but unable to react. For example, on a post where Dallagnol encouraged his audience to support political candidates that favored anticorruption reforms, users commented:

I hope that in 2018 the people learn how to vote: this is what I hope.

We are with you guys, I wanted to know how to bring people to reason after all that happened. There are still many people who do not wake up and remain in ignorance (same post).

However, in comments to this post there was also a shared sentiment, which later grows, that these same “people” should act and become a vector of change. Users wrote:

It is the Brazilian people who must fight against corruption. If people do not fight for their own good and are waiting for a superhero to come fight for them, they will wait forever. Because Brazil's fault lies in this situation of ours, so wake up. (same post).

Brazil still has a fix, it just depends on us taking action, yes, it must now be the power emanating from the patriotic Brazilian people!!! Thank you Mr. DALTON DALGNOL and all your fantastic team that is changing the country's history!! Always together with you for Brazil from my ![]() . (same post).

. (same post).

Again, Dallagnol consciously encouraged this activation of society to fight corruption. This first appears in the dataset in a 2018 post in which he asks whether LJ will change the country. His answer:

LJ breaks the impunity of the powerful and this is a sure step to law's empire, but … LJ alone will not change the country … systemic corruption is like apples rotting in a barrel … if you want to solve the problem you need to change the conditions … that make the apples rot.

He concluded, “We must change the political and business environment that currently favor corruption” and promised a series of videos to start “a conversation on what changes are needed and how we, as society, can get involved to interrupt the vicious cycle of Brazilian corruption.”

On many occasions thereafter, Dallagnol's posts called the people to engage. The way he did so, however, deserves careful consideration. In his study about the “political grammar” advanced by LJ legal officers from 2014 to 2018, which was heavily based on press interviews by Dallagnol, Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva (2020a) found that, while these agents initially credited the success of the operation to existing laws and institutions, they later came to see such laws and institutions as obstacles to anticorruption. They demanded the reform of institutions and pitted the people they claimed to represent against those who opposed the changes they wanted (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020a p. S106).

In data analyzed in this article, this is also the context in which society gets activated. Many of Dallagnol's posts targeted Congress—which he argued should be changed for the anticorruption cause to prosper—and invited some form of popular activism. In a post, Dallagnol recorded a video in which he argued that “people feel impotent, incapable” but could “make a leap by voting in candidates committed to (his) reformist agenda.” In another, he celebrated that “at least 10 big names involved in LJ lost (the 2018 elections)… ten Senators (with an anticorruption platform) were elected … and non-partisan movements elected many candidates.” A late 2018 news article argued that politicians who had been defeated in congressional elections were planning to lobby for laws to protect them from investigations. Dallagnol posted a video mentioning the article and argued: “Brazil is changing,” but “we need to defend LJ against attacks being staged in Congress” and “we will need to continue to count on your help.”

In 2019, Dallagnol started a campaign against secret voting in the congressional elections for the Speaker of the Senate, knowing that this would reduce the likelihood of a victory by Senator Renan Calheiros, whom he saw as a LJ adversary. After a heated debate on the Senate floor, secret voting was upheld, but the popular pressure was so intense that senators voluntarily opened their votes, showing the ballots to cameras or posting them on social media. Calheiros was defeated and Dallagnol wrote a post stating, “The sensitiveness of Senators regarding open voting shows the importance and the power of social mobilization.” He added: “The defeat of Renan Calheiros … also represents the rejection, by society … of somebody investigated for corruption in LJ.”

The STF became the most direct antagonist in Dallagnol's Facebook activity. Eleven of his 53 posts analyzed herein focus on the court or some of its justices. Once again, the posts both targeted the court and justices and invited popular activism. For example, in late 2018, Dallagnol posted a video about an upcoming STF deliberation that he considered “a matter of life and death for LJ” (Justices were to rule whether corruption cases involving the electoral use of slush funds should be tried by electoral courts, not the federal criminal courts trying LJ cases). He said that “two justices have already indicated that they will (accept this), which is very concerning.” He then concluded: “Let us hope that the Supreme Court will, once again, be along with LJ, along with society, in this important decision.” In 2019, when the STF was about to rule in this case, Dallagnol recorded and posted a video with the following script:

We are here close to the Supreme Court (turns the smartphone to film the STF building). The Court, in that building over there, will decide an issue on March 13 … that can void several lawsuits and affect LJ … (the decisions) can end LJ.

Yet as readers must have noticed in Graph 4, it was the STF's decision on the 2017 presidential pardon decree issued by then-president Michel Temer that best reflected those clashes.Footnote 29 A case against this pardon was brought in 2017 by the chief federal prosecutor, and Justice Roberto Barroso granted a preliminary injunction to suspend the president's decree. In late 2018, the Court began to review the case.Footnote 30 In 3 days—and in his usual alarmist tone—Dallagnol posted five times about the issue. One day, he wrote:

URGENT: There is (an) intense lobby before the Supreme Court this Wednesday to validate the presidential pardon given by Temer in 2017, which reduced by 80% the sentence of corrupts, whatever the jail time in the sentence was … This pardon transforms LJ's work and punishment for corruption into a joke. As we had anticipated, this is going to be a difficult holiday time for LJ, which continues to need your help—and by a lot. Take a stance. Share this!

Another day, he posted a link to a transmission of the STF session where this matter was to be decided,Footnote 31 adding:

Watch live, now, to the trial by the Supreme Court of Temer's presidential pardon, which can end LJ and ruin the effort that society made over the last years against corruption.

The engagement generated by these posts stands out in the data. Indultonao and indultonão (no to pardon) became the most-used words in the whole sample of comments analyzed in this article, after lava and jato (which inevitably appeared at the top).

“Out with the Supreme Court!” active citizens or crusaders against institutions?

Dallagnol's activation of society to join LJ in the fight against corruption is controversial. Many see it as a contribution to healthy civic participation in national life and politics and an enhancement of “vertical accountability”; others see it as foreign to prosecutorial work and as a problematic intrusion of law into politics. Some of the latter pointed out that the Brazilian constitution forbids prosecutors from engaging in partisan politics, and Brazilian electoral law punishes public authorities who “abuse their powers” to benefit specific candidacies. Dallagnol's actions could potentially have breached these and other legal rules. Indeed, in September 2020, Dallagnol was sanctioned by the National Council of Public Prosecution (CNMP) for interfering in the Speaker of the Senate election, though this did not affect his career as he benefited from statutes of limitation.Footnote 32 His STF criticisms faced similar backlash.Footnote 33 In August 2018, Dallagnol gave a radio interview in which he stated: “The same three Supreme Court justices who always take everything away from Curitiba (Sergio Moro's jurisdiction) and who send it to electoral courts and who always grant habeas corpus petitions, they are always forming a clique that sends a very strong message of leniency in favor of corruption.” The chief STF justice filed a complaint against him for these statements; this time—and for the first time—Dallagnol was effectively disciplined.Footnote 34 In July 2020, Dallagnol faced another complaint, initiated by the CNMP's comptroller,Footnote 35 for a tweet calling a STF decision “casuistic.”Footnote 36

In this article, the lawfulness, motivation, and politics of people's activation are less important. What matters is the culture of (il)legality it fosters or helps to reinforce. A close look at the comments on Dallagnol's posts reveals the terms of this culture. In response to Dallagnol's push for civic activism against corruption, some comments are consistent with democratic institutional oversight. For instance, amid Dallagnol's campaign against Temer's pardon decree and his call for people to “take a stance” and “share” his post, a user commented:

It is not enough to just share. Society needs to organize and, if these tricks come to fruition, go out into the streets en masse and DEMAND those who have committed crimes to pay for them. NO PARDON!

However, most of the comments in the sample have a different, less uplifting tone. On a post where Dallagnol criticized an STF decision, users suggested that a popular upheaval should be staged to overthrow the court:

Start with the insubordinations and you will have support from 100% of the population, get organized and stop respecting these decisions dammit!!! The Supreme Court has already lost legitimacy in Democracy for many years, and nobody does anything, are you waiting for barbarisms to happen? You are thousands of judges, prosecutors, attorneys and judges in lower and appellate courts against just 11 robed Supreme Court Justices, ![]() . this just does not add up! STF is acting like David and you guys like Goliath!!! This needs to change urgently!!

. this just does not add up! STF is acting like David and you guys like Goliath!!! This needs to change urgently!!

And:

I wanted Brazilians to show the same spirit they showed in the World Cup (when massive protests happened) and invade Brasília (Brazil's capital, where the STF is headquartered), I wanted to see if 200,000 people gathered in front of the STF if they would continue with this mess.

In posts in which Dallagnol commented on the STF trials of Temer's pardon decree, this mood deepened in the data. Users wrote:

The people must go to the streets against this pardon and against the STF.

The STF has become the biggest enemy of Brazil #SftShame.

A call for an investigation into the STF justices also appeared in the comments. According to a user:

Brazil urgently needs an Operation Clean Robe.Footnote 37

Others suggested an even more heterodox solution: military intervention and shutting down the STF:

Ah my friend … I can share it, but the only ones who can do anything, and now they can more than ever, are the Generals, intervening on the STF.

#STFNationalshame #NoToPardon #interventionintheSTF #Absurd #WeAreAllLavaJato #outwiththeSTF #pardonNo #lulaIncarcerated.

In early 2019, these dispositions were at the top of the comments' repertoire (Graph 5), with high frequencies registered for slogans and hashtags such as foratoffoli “out with Toffoli (the Chief STF Justice)” and forastf (“out with the STF”).

GRAPH 5 Frequency of most-used words in comments to the Facebook by Deltan Dallagnol (n = 53) and Carlos Lima (n = 1) in the top-756 posts with the terms “lava” and “jato” for a month in early 2019

Users then wrote:

Congress needs to URGENTLY put on, an impeachment process against the STF. (post where Dallagnol warned about the potential effects of a STF decision on LJ cases).

We Brazilians will have to go on the streets asking for impeachment of at least half of the STF Justices. On Facebook nothing gets resolved! (same post).

About a year after Lula's arrest, groups demonstrated in support of LJ in major Brazilian cities. The sentiment behind this event was articulated in the data in comments such as:

All on the streets on April 7. Follow the calls. Share. Invite friends. The force emanates from the people. #Lavajatostays #stfleaves (post where Dallagnol celebrated LJ's success).

Guys, I'm angry too, but on Sunday I'm on the streets, let us show our strength … #outwiththeSTF (post where Dallagnol lamented a STF decision for its potential effects on LJ cases).

And:

LJ is the hope of the Brazilian people. We are very proud of you! Thank you forever! #WeAreAllLavaJato #ISupportLavaJato #outwithGilmarMendes (an STF Justice) #outwithAlexandreDeMoraes (an STF Justice) #STFNationalShame (post where Dallagnol stated the importance of societal support to LJ's ultimate success).

These attacks on institutions resemble those later undertaken by the Brazilian far-right president Jair BolsonaroFootnote 38 and others.Footnote 39 In the United States, this had tragic developments when, on January 6, 2021, a far-right mob invaded the Capitol to impede the certification of electoral results and left a few people dead, following the calls by the former Republican president Donald J. Trump to “stop the cheat.”Footnote 40

The data in this article reveal that, if LJ legal officers did not create these dispositions, they may well have nurtured them in the Brazilian populace since mid-2018, if not before.Footnote 41 Messages leaked in the vaza jato scandal and operation spoofing indicate that Dallagnol and the task force often worked in conjunction with movements to name and shame congresspeople and STF justices.Footnote 42 In 2018 Dallagnol wrote to his peers that they:

should encourage the movements to shift their attention to Justice Alexandre de Moraes. If it sticks without being associated with our faces it's better; it could backfire if we put the STF against the wall. I posted about Moraes today, and whatever you want to post, go ahead, but I think the strategy of using the movements will be better, if it works.Footnote 43

By 2019, the affinities between Bolsonarismo and lava jatismo were harder to deny. In the agenda and iconography of the April 7, 2019 event cited above, support for LJ and for Bolsonaro, and hostility toward Congress and the STF, were impossible to disentangle.Footnote 44 In June 2019, following the vaza jato scandal, other protests occurred and were described by a news outlet as being “in support to Moro and against Congress and the STF.”Footnote 45

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

LJ has been, and will likely remain, a popular topic in corruption/anticorruption and law and society studies. This is not without reason. The operation used unorthodox means and had far-reaching consequences for economics and politics in Brazil and beyond. While LJ may fade and die, its story will not end anytime soon. Following vaza jato and operation spoofing, Brazilians have been inundated with new data on the operation daily, and many other data sources still await scholarly excavation for a more definitive account of LJ. In the meantime, the methods and legacy of LJ remain controversial.

This article focused on the exchanges between LJ prosecutors and people on Facebook from 2017–2019. These exchanges represented what the prosecutors considered a pillar of the operation (transparency). Using press conferences and public appearances on Facebook and Twitter posts, prosecutors sought to involve the people in every step of their work. Drawing from cultural analyses of corruption/anticorruption and recent developments in legal consciousness scholarship (relational legal consciousness), this article asked: What did these interactions amount to? Did they help nurture a virtuous, civic “spirit” that is about ending the “impunity of the wealthy” (Reference Bullock and StephensonBullock & Stephenson, 2020)? Or did they produce something different and perhaps more bitter?

The findings clearly support the more pessimistic view of LJ. In the interactions I studied, LJ was construed not as an institutional accomplishment, but as a divine or supernatural endeavor. The people were called to fight corruption, which turned not into a healthy engagement in public affairs and national life but into a crusade against institutions with fierce attacks on Congress and the STF. As such, LJ supported the coproduction of a cultural schema that not only was averse to the rule of law but may also have served as a foundation for Bolsonarismo.

This study has implications for both legal consciousness and anticorruption research. First, my findings invite research that takes seriously the role of social media platforms in altering and expanding the space in which sociolegal relationships unfold and meaning is given to law and, accordingly, that considers posts, comments, and the like as valid data sources. Social media have become a central feature of contemporary life, and scholars and thinkers are constantly trying to chart their impact on our individual behavior and societal arrangements. In this process, the role of social media platforms in the production of our cultural fabric is hard to deny. Nor can we deny that, in our everyday transactions, we—the digitally included—both download and upload elements from that cultural fabric or cloud to give meaning to what we think and do.Footnote 46 At the Senate's trial of Trump's second impeachment, his lawyer called the proceedings “constitutional cancel culture,” thereby downloading a (sociolegal) vocabulary from that cloud.Footnote 47 The #metoo movement can be seen as an example of sexual abuse victims uploading their grievances onto the cloud while re-creating the terms by which these grievances can be remedied (Reference Gash and HardingGash & Harding, 2018).

All this infinitely expands the possibilities for legal consciousness production and the social construction of legality, but not without risk. If legal consciousness research began as a critique of the cultural schemata that support the rule of law, it was because scholars had in mind the degeneration of modern societies into headless tyrannies (Reference ArendtArendt, 1972 p. 178; Reference Silbey and FeenanSilbey, 2013). Yet, as Silbey noted in her “After Legal Consciousness” essay:

In 2005, we continue to live in Weberian cages, but the metaphoric iron has become silicon and electromagnetic waves, the cage itself quite purposively against Weber's prediction re-enchanted. Tyranny now seems to flow through the silicon and electromagnetic connections between our incited fears/desires and the apparatuses that promise to protect us from reality while satisfying us with its image. (Reference SilbeySilbey, 2005 p. 358).

In this context, scholars must ask: How do processes of legal consciousness production happen in the digital age? To what extent are these processes shaped by technology and algorithms and subject not only to filter bubbles and echo chambers (Reference SunsteinSunstein, 2007), but also to platform business models that knowingly induce division and radicalization?Footnote 48 How do certain actors (the powerless and the powerful) take advantage of these new structural circumstances—and how may this vary based on their agendas, resources (e.g., to promote posts and pay for bots), and attributes? Are identities and frames first produced online and then deployed offline, or the opposite? How can the rule of law be strengthened and improved—or attacked and destroyed—through new forms of online and offline interaction if the two can be thought of separately at all? Unfortunately, due to methodological and ethical limitations, this paper could not attain some of these pieces of our new social. For example, one could posit that people who follow prosecutors and Dallagnol on Facebook are more likely to be commenting on their postsFootnote 49 and could share predispositions averse to the rule of law, which would explain the outcomes I observe. Because it is impossible to extract data from users—and it would be unethical to do so—drawing definitive conclusions on this matter was more difficult. Yet, the possibility that a lawyer carrying out an anticorruption operation in the name of the law could crowd in such an audience sounded no less disturbing as an interpretation of my findings.

Due to these methodological and ethical limitations, my study only partially captures the coproduction of meanings I set out to analyze. Using Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel's (2019) typology, one can say this article speaks mostly to a specific subset of relational legal consciousness research—the one concerned with the cultural schemata emerging from relationships and interactions (Table 1, “hegemony” column) in a sociolegal space radically altered by social media platforms. It remains unknown whether such schemata represent more of an aggregation of pre-existing dispositions among Dallagnol and his followers and interlocutors, or whether their respective identities and attitudes toward the rule of law were, indeed, transformed throughout—and, if so, how this happened and what caused these transformations among some, but perhaps not others. Future research can address these questions, for example, by following interactions in real time, interviewing their participants, and documenting changes in their profiles (what they used to post about, what they come to post). This article is only taking the first steps in an emerging, multilane avenue of sociolegal inquiry that must be explored further and in new, complementary directions. It is unquestionable, anyway, that Facebook both facilitated and potentiated those transactions—whatever they may have been, helped to amalgamate their resulting schemata, and gave them a place in the larger cultural space (Reference FoucaultFoucault, 1972) shared by many, if not all Brazilians living through the LJ rollercoaster.

These limitations aside, my findings suggest the need for research on relational legal consciousness to treat the issues of identity, mobilization, and hegemony identified by Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel (2019) in a more integrated fashion.Footnote 50 Indeed, along with the production of a cultural schema, my study indicates that identities emerged or were solidified, such as the divine judge/prosecutor and the active citizen fighting against corruption, which, in turn, did not remain restricted to digital life, but supported people's mobilization on the streets and in public debates, with attacks on Congress and the STF. The challenge to law's hegemony my research documents runs along all those three domains.

Yet this challenge also happens in new, provocative ways. Ewick and Silbey's paradigmatic work (1998, 2003) identified a form of challenge (in their words, “resistance”) that was ultimately reconcilable with the rule of law. Those who produced or drew from an against-the-law schema in their study did not reject law; they just felt that law was insensitive to their circumstances. Ever since, others have pointed to instances in which subjects understand law as a corrupt order that they are not willing to support and engage with (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020b; Reference FritsvoldFritsvold, 2009; Reference Halliday and MorganHalliday & Morgan, 2013; Reference HertoghHertogh, 2018). This article shows the importance of meticulously looking at these pockets of legal detraction, particularly at a time when the rule-of-law consensus is being threatened by rising autocrats. What are the similarities and differences in law's detraction among radical environmentalists (Reference FritsvoldFritsvold, 2009; Reference Halliday and MorganHalliday & Morgan, 2013), anti-torture activists (Reference de Sa e Silvade Sa e Silva, 2020b), and the far-right mobs that invaded the US Capitol or rallied against the Brazilian STF? What explains law's rejection in their respective cultural worlds, and what alternatives to the rule of law—desirable or not—might they support? Who builds on this hostility to the rule of law, and who fosters it—and why? Which means, digital and otherwise, are being used in these processes?

Finally, my study suggests that scholars should pay greater heed to the ways in which consciousness and ideology can become constitutive of anticorruption initiatives. Perhaps due to their policy orientation, most anticorruption studies seem to adopt an instrumental rather than a constitutive perspective (Reference Engel, Bryant and SaratEngel, 1998; Reference Sarat, Kearn, Sarat and KearnsSarat & Kearn, 1993). Culture appears in these studies as either a dependent variable (something that needs to be changed) or an obstacle to an external and benign—or at least well-intentioned—intervention. My findings indicate that culture is a social construct that is being coproduced through the interventions and, as such, that some anticorruption crusaders may be the authors as much as they are the victims of their failures.