In 2017, the yearly anthology Best American Comics published the works of five creators with mental disabilities. This unprecedented initiative demonstrates the continuously growing interest of the comics’ world for art pieces commonly described as ‘outsider’. Whether in Europe or in North America, this pattern is particularly obvious in the case of alternative creators and editors. In 1990, Henry Darger's huge compositions depicting an imaginary war between the little Vivian Girls and cruel men in uniforms were already reproduced in Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman's Raw (Mouly and Spiegelman, Reference Mouly and Spiegelman1990).

This magazine is often regarded as the inaugural act of the alternative comics movement. Alternative comics stand out for their desire not to adopt the standard forms of mainstream publications and to open up new fields of potentials. The reinvention of topics, stylistic approaches, storytelling schemes or relations between texts and images are coupled with a strong curiosity for other forms of graphic narratives. Moreover, there is a significant tendency to incorporate works associated with other artistic domains into the comics’ field (Dejasse, Reference Dejasse2012). French cartoonist and publisher Jean-Christophe Menu observes the existence of a ‘corpus hors-champ’ which also includes creators who have done comics even ‘without knowing it’ (Menu, Reference Menu2011). The ongoing redefinition of boundaries implies the rewriting of comics history. Thus, the wordless woodcut novel The Idea by Frans Masereel, the collage sequence A Week of Kindness by Max Ernst or the unlikely battles on long rolls of paper by Henry Darger all tend to be retrospectively annexed.

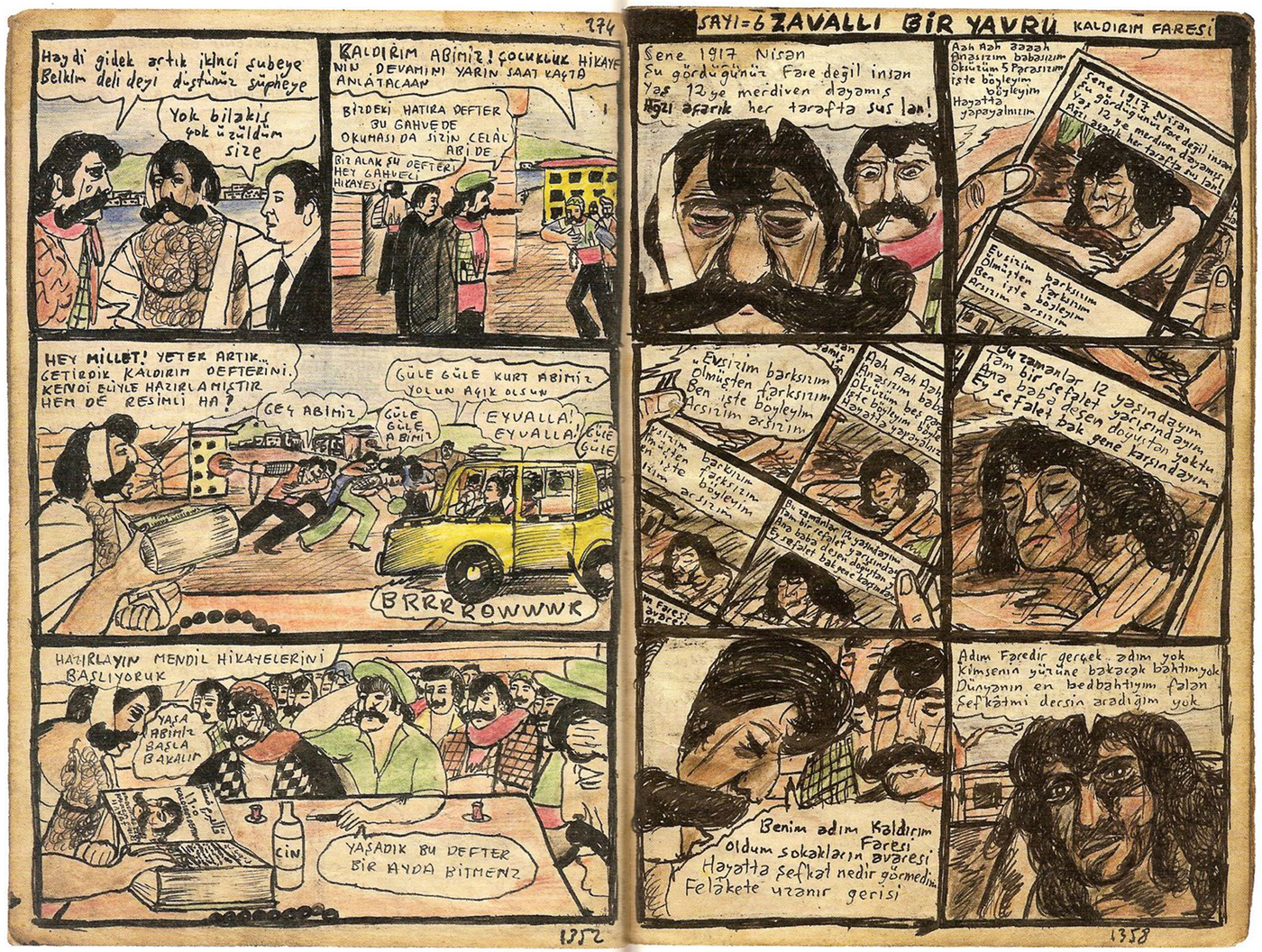

However, there are still plenty of works waiting to be discovered in the ‘corpus hors-champ’. Although it uses all the typical devices of comics – dialogues kept in speech balloons, sequences of framed images, even the comic book format –, Kaldırım Destanı – Kaldırımlar Kurdunun hayatı (Pavement Myth – The Life of the Pavement's Wolf) (Fig. 1) by Turkish self-taught creator Masist Gül (1947–2003) only draw little attention from comics artists, editors and critics. As in the case of Henry Darger, his drawings were completely unknown during his lifetime – only a few close friends saw them – and would probably have remained so without the sharp eye of another artist (Vazquez, Reference Vazquez2009). Banu Cennetoğlu discovered these just after Gül's dead and exhibited all of them in BAS, an exhibition space she was running in Istanbul. She also published a facsimile of the six handmade comic books forming Kaldırım Destanı (Gül, Reference Gül2006).

Fig. 1. Masist Gül, Kaldirim Destani – Kaldirimlar Kurdunun Hayati © BAM.

Using felt-tip markers, Gül roughly executed drawings that are characterised by a naive-expressionist albeit powerful and visionary graphic style. These 300 pages tell a never-ending lament covering 68 years with texts using rhymes. It contains numerous ultra-violent fighting scenes that are reminiscent of the artist's day job: Gül was indeed a bodybuilder who acted as big moustache villain in some 300 movies, from local blockbusters to obscure low budget films. Like many alternative comics, Kaldırım Destanı contains a lot of autobiographical elements. According to those that were close to him, the series of terrible hardships described here is a transposition of Gül's own life; a life of domestic violence, loneliness, alcoholism, mental breakdown and bitter love disappointment. As I have argued elsewhere, within the alternative movement, the cartoonists often spill over in other creative fields as they consider comics as part of their comprehensive artistic project (Dejasse, Reference Dejasse2010). Similarly, Masist Gül made paintings, poetries or collage that often include photographic self-portraits; an incredible production of texts and images where comics form the artistic core.

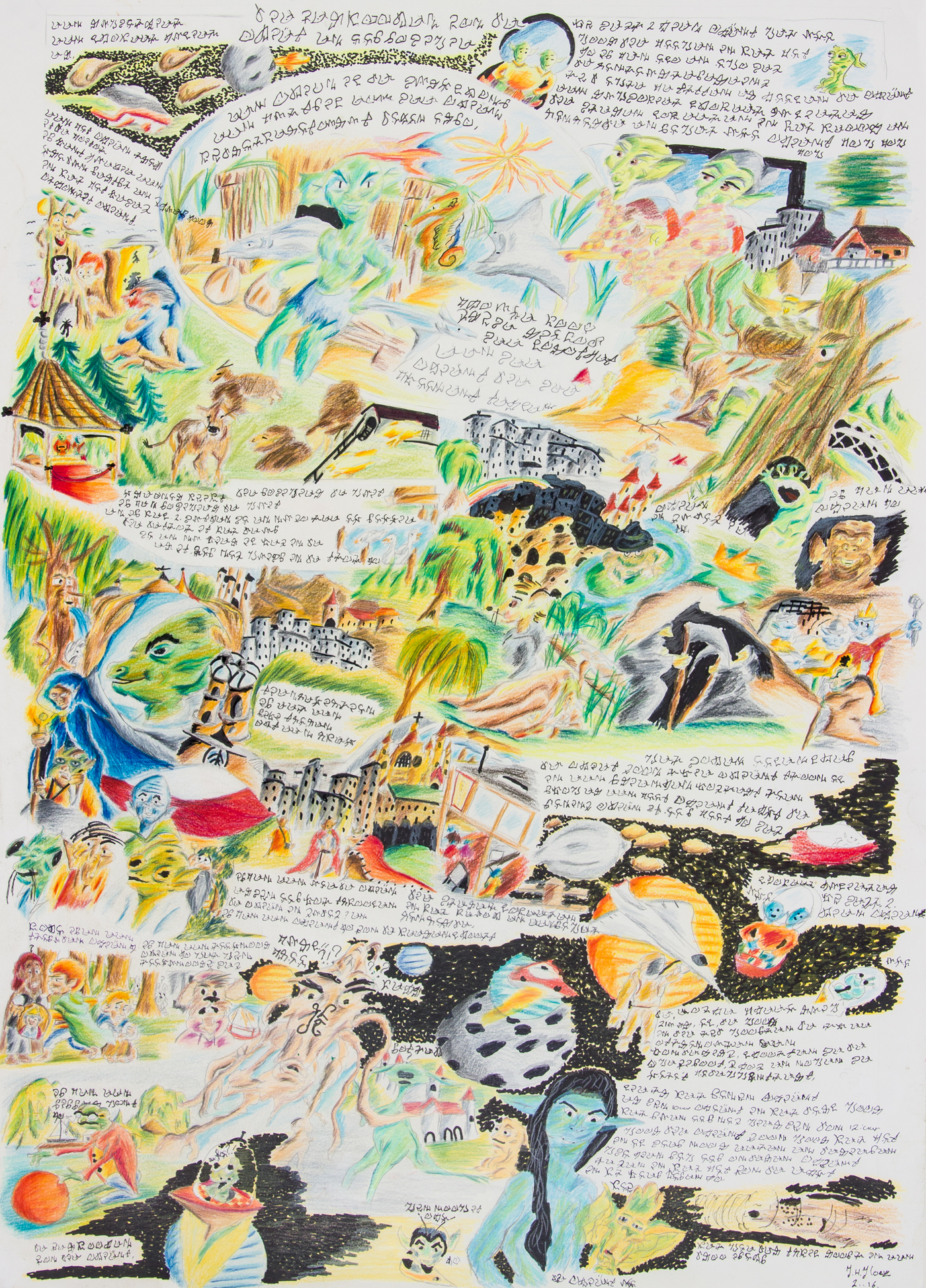

The same holds true in the case of Jacqueline Loeve (b. 1968): the content of her autonomous images incorporate subjects and topics that had already been seen in her comics. Since 1999, she is a member of Herenplaats, a pioneering studio for people with mental disabilities in Rotterdam (Dotulong and Houdijk, Reference Dotulong and Houdijk2016). She has also a part-time job in an educational farm where she cares for the animals. Her drawings depict extra-terrestrial beings, spaceships and planets covered with lush vegetation. She particularly did a remarkable series of large-scale colourful pages drawn with pencils, using an almost psychedelic colour palette: orange, apple green and lemon yellow. Rather that developing a storyline, she juxtaposes slices of life. By showing the aliens going on holiday, visiting a megapolis or having a trip in forest, her comics resemble a travel guide of her idiosyncratic universe. The text is written in Dutch or in an extra-terrestrial language: while the latter is unreadable, the construction of the words and their arrangement clearly seems to follow a certain logic. The panels are not divided into frames but interpenetrate each other, the layout break up to the extent that the reading process has to be modified. To read it properly, you have to turn the page in every direction. If Jacqueline Loeve clearly states that she is making comics, she breaks with the usual patterns and reinvents its plastic-narrative devices (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Jacqueline Loeve, untitled © Herenplaats.

Outsider art works were made below the cultural radar. Therefore, the usual dichotomy between high and low art is ineffective: outsider artists are not afraid of reusing the codes of comics as they are far from an idea that has deeply permeate 20th century art: ‘telling a story is taboo’.