Introduction

Childhood victimisation (including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, exposure to domestic violence, and bullying by peers) can have lifelong adverse effects, with an elevated risk of psychopathology in early adulthood, especially when multiple forms of victimisation (or poly-victimisation) are experienced (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alhamzawi, Alonso, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bromet, Chatterji, de Girolamo, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Florescu, Gal, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Lépine, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Tsang, Ustün, Vassilev, Viana and Williams2010; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, McElroy, Elklit, Shevlin and Christoffersen2020). Early adulthood is a critical developmental period to study as over 75% of adult mental health disorders have their onset by age 18 (Kim-Cohen et al., Reference Kim-Cohen, Caspi, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne and Poulton2003). Moreover, there is a high co-occurrence of psychopathology in early adulthood with nearly half of individuals with a mental disorder (comprising internalising, externalising and thought disorders) found to experience at least one additional mental disorder concurrently at age 21 (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Moffitt, Caspi, Magdol, Silva and Stanton1996) and by mid-life 85% have been shown to experience more than one type of mental disorder (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Ambler, Danese, Elliott, Hariri, Harrington, Hogan, Poulton, Ramrakha, Rasmussen, Reuben, Richmond-Rakerd, Sugden, Wertz, Williams and Moffitt2020). Therefore, it does not make sense to examine individual mental disorders. Furthermore, since victimisation exposure has been associated with nonspecific effects on multiple mental disorders (Daníelsdóttir et al., Reference Daníelsdóttir, Aspelund, Shen, Halldorsdottir, Jakobsdóttir, Song, Lu, Kuja-Halkola, Larsson, Fall, Magnusson, Fang, Bergstedt and Valdimarsdóttir2024; Meehan et al., Reference Meehan, Latham, Arseneault, Stahl, Fisher and Danese2020), its relationship with a general factor of psychopathology that captures the propensity to develop any type of mental disorder, also called ‘p’, is of interest (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev and Poulton2014; Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Moffitt, Arseneault, Danese, Fisher, Houts, Sheridan, Wertz and Caspi2018).

Although childhood victimisation significantly increases the risk for early-adulthood psychopathology, not all victimised children develop mental health difficulties in adulthood. For example, Meehan et al. (Reference Meehan, Latham, Arseneault, Stahl, Fisher and Danese2020) found that 39.6% of victimised children within a British longitudinal cohort did not meet diagnostic criteria for any psychiatric disorder by age 18 years. Identifying factors that can protect such victimised children from developing early-adulthood psychopathology may help inform the content of targeted preventive mental health interventions. Protective factors for psychopathology are likely to be identified at various system levels (individual-, family- and community-level) and interact with each other, which is why the most effective interventions often focus on targeting protective factors across these levels (Ungar et al., Reference Ungar, Ghazinour and Richter2013; Ungar and Theron, Reference Ungar and Theron2020). At the individual level in childhood, these factors may include cognitive abilities (e.g., relatively high intelligence quotient [IQ], strong executive functioning), self-regulation (e.g., internal locus of control, an easy-going temperament, cognitive flexibility, ego-control), adaptive coping skills, and prosocial behaviour, all of which may enable children to seek help following victimisation (Nelson-Le Gall, Reference Nelson-Le Gall1981) and respond adaptively to these stressful experiences (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen and Wadsworth2001), thus mitigating victimisation’s adverse effects on antisocial behaviour and adult mental disorders (Jaffee, Reference Jaffee2017; Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomás and Taylor2007; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). At the family and community levels, protective factors may provide a safe environment where the child can seek help and find support to compensate for victimisation (Ozer et al., Reference Ozer, Lavi, Douglas and Wolf2017). Family-level characteristics that have been shown to be protective against emotional and behavioural problems and mental disorders in children exposed to various forms of victimisation encompass warmth from the mother towards the child, parental monitoring, family cohesion, living in a nurturing home environment, and the quality of siblings’ relationships with one another (Bowes et al., Reference Bowes, Maughan, Caspi, Moffitt and Arseneault2010; Collishaw et al., Reference Collishaw, Pickles, Messer, Rutter, Shearer and Maughan2007; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). Additionally, community-level characteristics, such as social cohesion within the surrounding neighbourhood, have been shown to protect victimised children from developing psychotic experiences and other psychopathology (Crush et al., Reference Crush, Arseneault, Jaffee, Danese and Fisher2018a; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). Lastly, access to socially supportive relationships within the family (e.g., parents and siblings) and in the wider community (e.g., friends, teachers, neighbours) have also been found to exert a protective influence against a wide range of mental health difficulties among children exposed to violence and other forms of victimisation within and outside of the home (Collishaw et al., Reference Collishaw, Pickles, Messer, Rutter, Shearer and Maughan2007; Crush et al., Reference Crush, Arseneault, Moffitt, Danese, Caspi, Jaffee, Matthews and Fisher2018b; Jaffee, Reference Jaffee2017; Latham et al., Reference Latham, Arseneault, Alexandrescu, Baldoza, Carter, Moffitt, Newbury and Fisher2022).

However, our understanding of factors associated with lower levels of psychopathology in early adulthood is limited, primarily because previous studies have often focused on specific mental disorders (Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). This narrow focus can reduce the ability to identify associations resulting from unaddressed similarities between interrelated disorders (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Fisher, Danese and Moffitt2024). It is also based on studies focusing on psychopathologies that are present in childhood or early adolescence, whose results may not be generalisable to psychopathology in early adulthood (Crush et al., Reference Crush, Arseneault, Jaffee, Danese and Fisher2018a). Moreover, some research has focused on specific types of childhood victimisation that can either strengthen or weaken associations (Herrenkohl et al., Reference Herrenkohl, Tajima, Whitney and Huang2005) and this does not reflect real-world experiences where children are often exposed to more than one type of victimisation (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Finkelhor and Ormrod2010). Others have investigated childhood poly-victimisation through retrospective self-reports (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, MacMillan, Taillieu, Turner, Cheung, Sareen and Boyle2016), often capturing different groups of victimised children compared to those identified with prospective measures (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury and Danese2019).

To address these knowledge gaps, the present study utilises prospectively collected data from the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, a large, nationally representative cohort of children born in the UK. Potential protective factors were selected based on the existing literature, their ability to reflect three system levels within which children grow up (individual-, family-, community-level factors), as well as their availability within the E-Risk cohort, and their relevance for developing and targeting effective preventive interventions. Therefore, our aim was to investigate whether specific individual factors (IQ, executive functioning, approach temperament), family-related factors (maternal warmth, sibling warmth, atmosphere at home, maternal monitoring), community-related factors (neighbourhood social cohesion) and family- and community-related factors (presence of a supportive adult) were (i) associated with lower levels of general psychopathology at age 18 among poly-victimised children (i.e., were protective against poor mental health in this high-risk group) and (ii) also associated with fewer mental health difficulties in young adults regardless of whether they had or had not been poly-victimised (i.e., were more widely promotive of good mental health in the general population; Brumley and Jaffee, Reference Brumley and Jaffee2016).

Methods

Study cohort

Participants were members of the E-Risk Longitudinal Twin Study, which tracks the development of a nationally representative birth cohort of 2,232 twin children born in England and Wales in 1994–1995. Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere (Moffitt and E‐Risk Study Team, Reference Moffitt and E-Risk Study Team2002) and in Supplementary Text 1. Briefly, the E-Risk sample was constructed in 1999–2000 when 1,116 families (93% of those eligible and of whom 90.4% were White) with same-sex 5-year-old twins participated in home-visit assessments. This sample comprised 56% monozygotic and 44% dizygotic twin pairs; sex was evenly distributed within zygosity (49% male). Families were recruited to represent the UK population of families with newborns in the 1990s, on the basis of residential location throughout England and Wales and mother’s age.

Follow-up home-visits were conducted when children were aged 7, 10, 12 and 18 (participation rates were 98%, 96%, 96% and 93%, respectively). At age 18, a total of 2,066 participants were assessed. Average age at time of assessment was 18.4 years (standard deviation [SD] = 0.36); all interviews were conducted after the 18th birthday. There were no differences between those who did and did not take part at age 18 in terms of socioeconomic status (SES) assessed when the cohort was initially defined (χ2 = 0.86, p = .65), age-5 IQ scores (t = 0.98, p = .33), age-5 internalising or externalising behaviour problems (t = 0.40, p = .69 and t = 0.41, p = .68, respectively) or childhood poly-victimisation (z = 0.51, p = .61). The Joint South London and Maudsley and Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee approved each study phase. Parents gave informed consent and twins gave assent between 5 and 12 years and then informed consent at age 18. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (von Elm et al., Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007).

Measures

Childhood victimisation

Prospective measures of victimisation utilised in this cohort and the coding criteria are described elsewhere (Danese et al., Reference Danese, Moffitt, Arseneault, Bleiberg, Dinardo, Gandelman, Houts, Ambler, Fisher, Poulton and Caspi2017; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Caspi, Moffitt, Wertz, Gray, Newbury, Ambler, Zavos, Danese, Mill, Odgers, Pariante, Wong and Arseneault2015) and in Supplementary Text 2. In brief, lifetime exposure to several types of victimisation was assessed repeatedly when children were 5, 7, 10 and 12 years. Comprehensive dossiers were compiled for each child with cumulative information about: exposure to domestic violence between mother and partner; frequent bullying by peers; physical abuse by an adult; sexual abuse; emotional abuse and neglect; and physical neglect, between birth and age 12. Dossiers comprised reports from caregivers, recorded narratives of caregiver interviews, recorded debriefings with research workers who had coded any indications of abuse and neglect at any of the successive home visits, interviews with children about their bullying experiences, and information from clinicians whenever the study team made a child-protection referral. These were reviewed by two independent researchers and rated for the presence and severity (none/mild/severe) of each type of victimisation. For example, children in families in which no physical violence took place were coded as not having been exposed to domestic violence; children in families in which physical violence took place on one occasion were coded as having been exposed to mild domestic violence; and children in families in which physical violence took place on multiple occasions were coded as having been exposed to severe domestic violence. How the severity of each type of victimisation was defined is provided in Supplementary Text 2. Poly-victimisation was defined as experiencing two or more types of mild or severe victimisation before age 12 (N = 720, 35%) compared to one or none (N = 1,346, 65%).

For sensitivity analyses, we used victimisation measured retrospectively using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire when participants were aged 18 (Bernstein and Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998; Newbury et al., Reference Newbury, Arseneault, Moffitt, Caspi, Danese, Baldwin and Fisher2018) (Supplementary Text 2). Participants reported on their personal experiences of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect, for the period before they were aged 12. For comparability to the prospective measure of poly-victimisation, we added domestic violence and bullying by peers from the prospective report to the ‘self-reported victimisation’ variable. Retrospective poly-victimisation was defined as experiencing two or more types of moderate or severe victimisation before age 12 (N = 556, 27%) compared to none or mild victimisation (N = 1,510, 73%).

Early-adulthood psychopathology

We utilised a continuous latent factor of general psychopathology, also known as ‘p’, derived using a confirmatory factor analysis by fitting a bi-factor model to 11 symptom scales (post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, disordered eating, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, alcohol dependence, cannabis dependence, nicotine dependence, psychotic symptoms, and prodromal symptoms) obtained from data collected during private interviews with each twin at age 18 about psychopathology in the previous year (Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Moffitt, Arseneault, Danese, Fisher, Houts, Sheridan, Wertz and Caspi2018) (see Supplementary Text 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). For sensitivity analyses, we also utilised the three specific underlying dimensions of psychopathology (internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms, and thought disorder symptoms) derived from the bi-factor model (see Supplementary Text 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). All scores were scaled to a mean of 100 and SD of 15.

Putative protective factors

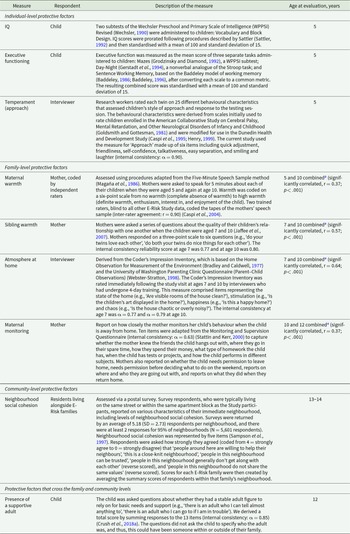

Table 1 provides information on the measures, sources, and age at which individual factors (IQ, executive functioning, approach temperament), family-related factors (maternal warmth, sibling warmth, atmosphere at home, maternal monitoring), community-related factors (neighbourhood social cohesion) and family- and community-related factors (presence of a supportive adult) were obtained.

Table 1. Description of the putative protective factors analysed in this study

E-Risk, Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study; IQ, intelligence quotient.

a Averaged to provide a single score. In the absence of one measure, the available score was utilised.

Confounders

The biological sex of the child was reported by mothers at birth. Family SES was measured via a composite of total household income, highest maternal/paternal education and highest maternal/paternal occupation when children were aged 5. These three indicators were highly correlated (r values ranged from 0.57 to 0.67, all p values < .05) and loaded significantly onto one latent factor (factor loadings = 0.80, 0.70 and 0.83 for income, education and occupation, respectively). This latent variable was then categorised into tertiles (i.e., low-, medium- and high-SES) (Trzesniewski et al., Reference Trzesniewski, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor and Maughan2006). In private interviews when the children were aged 12, mothers reported on family history of DSM disorders (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Wickramaratne, Adams, Wolk, Verdeli and Olfson2000), which was converted to a proportion (0–1.0) of family members with a history of psychiatric disorders (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Moffitt, Crump, Poulton, Rutter, Sears, Taylor and Caspi2008).

Statistical analyses

The premise and analysis plan for this project were preregistered at https://sites.duke.edu/moffittcaspiprojects/files/2023/12/Blangis_2023_Protective-factors-and-psychopathology.pdf. We conducted multiple linear regression analyses within STATA 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and accounted for the non-independence of our twin observations in all analyses using the Huber–White variance estimator (Rogers, Reference Rogers1993). First, we tested associations between the presence/absence of childhood poly-victimisation and levels of general psychopathology at age 18 in the whole sample to establish whether poly-victimised children had elevated psychopathology in early adulthood compared to their non-poly-victimised peers. Second, we investigated the associations between each putative protective factor and levels of general psychopathology at age 18 within the subsample of poly-victimised children to examine if any of these exerted a protective effect in this high-risk group. We utilised standardised beta coefficients to compare the relative impact of each factor on general psychopathology. Third, in the whole sample, we tested interactions between childhood poly-victimisation and the putative protective factors found to be significantly associated with lower levels of general psychopathology in step 2, and their associations with general psychopathology at age 18. This tested whether these factors were associated with reduced psychopathology only in poly-victimised children (significant interaction) or also in non-poly-victimised children (no interaction and evidence of a main association) and thus might be exerting a promotive effect in the whole sample. All these analyses were subsequently adjusted for biological sex, family SES, and family psychiatric history to take into account these potentially confounding factors. The precision of the estimated associations was determined using 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and those that did not include zero were considered to indicate statistical significance at p< .05.

Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses by repeating the first two steps, limiting the analyses to the factors found to be significantly associated with lower general psychopathology in the main analyses: (i) separately for each of the three domains of early-adulthood psychopathology (internalising, externalising and thought disorder symptom dimensions); (ii) using retrospective assessments of childhood maltreatment obtained at age 18 to define which children had experienced poly-victimisation; and (iii) defining poly-victimisation using only types of victimisation rated as severe. The latter two sensitivity analyses were conducted with general psychopathology as the outcome and then with the three specific domains of early-adulthood psychopathology as the outcomes. Analyses reported here were checked for reproducibility by an independent data-analyst, who recreated the code by working from the manuscript and applied it to a fresh dataset.

Results

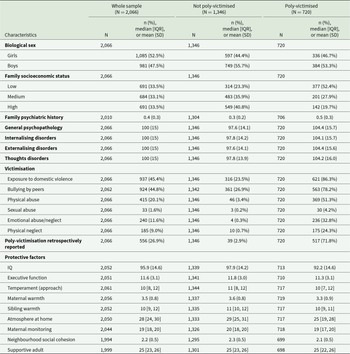

The characteristics of children included in the analysis (N = 2,066) are provided in Table 2, for the sample overall and separately for children who were and were not poly-victimised. Approximately a third (n = 720) of twin participants were prospectively defined as exposed to poly-victimisation (53.3% male). The most common forms of victimisation among poly-victimised children were exposure to domestic violence (86.3%; n = 621) and being bullied by peers (78.2%; n = 563). Among the prospectively defined poly-victimised children, 71.8% (n = 517) retrospectively reported having experienced poly-victimisation. Just over half of the prospectively defined poly-victimised children grew up in low SES families (52.4%), and on average they had a greater proportion of family members with a psychiatric history and slightly higher mean psychopathology scores than non-poly-victimised children (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of children in the whole sample and separately for children who were and were not poly-victimised

IQ, intelligence quotient; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Is poly-victimisation in childhood associated with early-adulthood psychopathology?

Poly-victimised children had greater levels of general psychopathology at age 18 (mean = 104.4; SD = 15.7) than non-poly-victimised children (mean = 97.6; SD = 14.1) (unadjusted β = 6.74; 95% CI 5.19, 8.30). The association was slightly attenuated but remained robust after adjusting for the child’s biological sex, family SES, and family history of mental health disorders (adjusted β = 4.80; 95% CI 3.13, 6.47).

Are individual-, family- or community-level factors associated with lower levels of general psychopathology among poly-victimised children?

Associations between each putative protective factor and general psychopathology at age 18 within the sub-group of poly-victimised children (N = 720) are presented in Table 3. Presence of a supportive adult was the only factor that demonstrated a robust association with lower levels of general psychopathology among poly-victimised children (adjusted β = −0.61; 95% CI −0.99, −0.23). Compared to the other factors, presence of a supportive adult had the strongest effect (standardised β = −0.15). Small protective effects were observed for a positive atmosphere at home (standardised β = −0.08), higher maternal monitoring (standardised β = −0.05), and greater neighbourhood social cohesion (standardised β = −0.06), but these associations were not statistically significant after accounting for potential confounders, and the relatively wide 95% CIs for social cohesion indicated this estimate was particularly imprecise. None of the individual factors were found to be protective in this poly-victimised group.

Table 3. Associations between individual-, family- and community-level factors and general psychopathology among poly-victimised children

CI, confidence interval; IQ, intelligence quotient.

All analyses account for the non-independence of twin observations.

The n varied from n = 685 to n = 719, due to different levels of completion of the measures.

Bold text indicates 95% CIs that do not include zero.

a Each factor was tested in separate linear regression models.

b Adjusted for biological sex, family socioeconomic status, and family history of psychiatric disorders.

Are these factors specific to poly-victimised children?

Within the whole sample (including those who were and were not exposed to poly-victimisation), the presence of a supportive adult was associated with lower levels of general psychopathology (unadjusted β = −0.54; 95% CI −0.82, −0.25) even following adjustment for potential confounders (adjusted β = −0.52; 95% CI −0.81, −0.24). The protective influence of this factor on psychopathology was not specific to poly-victimised children given that no significant interaction was observed between poly-victimisation and the presence of a supportive adult in the whole sample (unadjusted β interaction = −0.11; 95% CI −0.57, 0.35; and adjusted β interaction = −0.09; 95% CI −0.56, 0.38).

Sensitivity analyses

First, consistent patterns of associations were observed when dividing early-adulthood psychopathology into internalising, externalising and thought disorder symptom dimensions (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Second, similar results were observed when childhood victimisation was (partially) measured retrospectively at age 18 (Supplementary Tables S1, S3 and S4).

Third, when restricting exposure to two or more types of severe victimisation in childhood, associations of a similar magnitude were observed although these were non-significant (Supplementary Tables S1, S5 and S6).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated individual-, family- and community-level putative protective factors between childhood poly-victimisation and early-adulthood psychopathology. We found that the presence of a supportive adult at age 12 was significantly associated with lower levels of general psychopathology in early adulthood among poly-victimised children and also in young adults regardless of whether they had or had not been poly-victimised. Additionally, there was weak evidence from the adjusted standardised beta coefficients that a positive atmosphere at home, greater maternal monitoring, and higher neighbourhood social cohesion were associated with lower levels of general psychopathology in poly-victimised children, but the 95% CIs for these included zero and were therefore not statistically significantly. No individual factors were found to be associated with less early-adulthood general psychopathology. Sensitivity analyses investigating psychopathology split into its three main domains, childhood victimisation measured (partially) retrospectively at age 18, and when restricting to children exposed only to severe poly-victimisation, yielded associations of similar magnitudes. This suggests that the protective effects found may occur across the spectrum of mental health difficulties (rather than being specific to particular types of mental health difficulties) and largely hold regardless of whether prospective or retrospective reporting methods are utilised and the severity of victimisation experienced. It is important to note though that the associations for severe poly-victimisation were not statistically significant, which may have been due to the small size of this subgroup.

The main finding of this study was the robust promotive effects on mental health observed for the presence of a supportive adult. This finding aligns with previous research, suggesting that having at least one adult to whom children can turn is important in reducing the development of mental health difficulties, particularly for poly-victimised children (Jaffee, Reference Jaffee2017; Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomás and Taylor2007; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). Studies have suggested that social support may have a stress-buffering effect, particularly by influencing the child’s biological responses to toxic stress (e.g., victimisation), or a direct effect on mental health through the development of secure and trusting relationships (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Stevens, Purtscheller, Knapp, Fonagy, Evans-Lacko and Paul2021; Cohen and Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985; Jackson and Deye, Reference Jackson and Deye2015). The promotive effect of having a supportive adult was present regardless of poly-victimisation during childhood, consistent with existing literature (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Steel and DiLillo2013; McLewin and Muller, Reference McLewin and Muller2006). More research is therefore needed on the promotive effects on mental health of having a supportive adult in childhood among individuals within the general population who have not been exposed to specific risk factors.

Based on the effect sizes, we found small, but not statistically significant, protective effects for a positive atmosphere at home, greater maternal monitoring, and higher neighbourhood social cohesion factors. This is partially consistent with previous research that demonstrated how a caring and nurturing home environment can help a child who has experienced poly-victimisation to adjust, leading to improved mental health outcomes (Egeland et al., Reference Egeland, Carlson and Sroufe1993). Additionally, higher parental monitoring has been proposed to make a child feel looked after and supported (Ceballo et al., Reference Ceballo, Ramirez, Hearn and Maltese2003) and has been associated with lower levels of internalising and externalising problems (Kerr and Stattin, Reference Kerr and Stattin2000), including among those exposed to violence (Bacchini et al., Reference Bacchini, Concetta Miranda and Affuso2011), though findings related to antisocial behaviour are mixed (Wertz et al., Reference Wertz, Nottingham, Agnew-Blais, Matthews, Pariante, Moffitt and Arseneault2016). Furthermore, living in a socially cohesive neighbourhood may provide opportunities for children to turn to those outside of their home for support following victimisation and promote better mental health (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, Reference Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn2000). Future studies should explore the potentially protective effects of these factors among larger numbers of poly-victimised children.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, we utilised a nationally representative cohort study which allowed the collection of prospective measures of poly-victimisation, putative protective factors and mental health. Second, unlike other studies on this topic (Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019), we defined psychopathology as a general factor as well as three dimensions of mental health symptoms, allowing for greater generalisability of our findings. Third, poly-victimisation was assessed both prospectively and retrospectively, allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of the associations using different measures of poly-victimisation (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury and Danese2019). Fourth, we conducted several sensitivity analyses that provided some reassurance about the consistency of the findings.

Our study also has several limitations. First, we assessed poly-victimisation during childhood without precise timing of exposure. Studies have shown that the impact of childhood adversity on mental health varies according to sensitive periods (McLaughlin, Reference McLaughlin2016; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, McElroy, Elklit, Shevlin and Christoffersen2020). Knowing more about the temporality of each form of victimisation would also be beneficial for proposing targeted preventive interventions based on the age at which victimisation occurs. Second, we were not able to identify who the supportive adult was. Knowing whether the adult was a family member, someone from outside the family, from the neighbourhood or associated with the school, could provide valuable insights to inform preventive interventions, as the strength of the associations may differ depending on these factors. The promotive effect of the presence of a supportive adult may also vary according to the children’s state of mind, their perception of support, self-image, and social network (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Stevens, Purtscheller, Knapp, Fonagy, Evans-Lacko and Paul2021). A study that is able to adjust for these variables and provides a more quantitative measure of the children’s social network, such as the number of sources of support, would allow for a more precise evaluation of the effect of having a supportive adult (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Quigg, Bates, Jones, Ashworth, Gowland and Jones2022). Third, we assessed the role of maternal warmth and monitoring but did not evaluate these factors in relation to fathers. Including these aspects of parenting from fathers in future studies would provide more comprehensive information. Fourth, we constructed the retrospective measure of poly-victimisation by including domestic violence and peer bullying from the prospective reports, as they were missing from the retrospective measures. This adjustment could have inadvertently strengthened the associations, especially given the high prevalence of domestic violence and bullying in the prospective reports. In addition, we included mild victimisation in the definition of poly-victimisation in the prospective measure, but not in the retrospective measures of maltreatment. This may have weakened the associations found with the retrospective measures though prevalence rates were similar. Fifth, we were unable to examine interactions with biological sex and SES due to insufficient power. Future studies using larger samples should consider including these interactions. Sixth, we did not assess whether the children in this sample had received any interventions, such as therapy, or consider a wider range of potential confounding factors, such as genetics, that may have influenced the association between poly-victimisation and psychopathology. Seventh, protective factors may vary over time and place, for example, according to societal and political developments (Ungar et al., Reference Ungar, Theron and Höltge2023). Our participants were born in the mid-1990s and all assessments were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated psychological distress (Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Steinhoff, Bechtiger, Murray, Nivette, Hepp, Ribeaud and Eisner2022). Further research is needed to validate our findings in current contexts. Finally, our results are derived from a cohort of predominantly White twins and the results may differ in the singleton population or in other ethnic groups. Although our findings have limited generalisability to ethnic minority groups within the UK, the E-Risk study population is representative of UK families in terms of geographical and socioeconomic distribution (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Taylor, Moffitt and Plomin2000; Moffitt and E‐Risk Study Team, Reference Moffitt and E-Risk Study Team2002), the prevalences of different types of victimisation among poly-victimised twins were similar to those reported in a non-twin study (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Finkelhor and Ormrod2010), and no significant differences in mental health difficulties have been reported between twins and singletons (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Martin, Heath and Eaves1995).

Implications

Our findings have practical implications. First, the promotive effect observed for the presence of a supportive adult suggests that early interventions aimed at increasing the availability of supportive figures in a child’s life or their perceptions of existing support may protect against the development of psychopathology in early adulthood. Interventions could, for example, focus on improving the relationship between children and their caregivers, ensuring schools have dedicated counsellors, enhancing the role and recognition of natural mentors (i.e., supportive adults outside the immediate family; Hurd and Zimmerman, Reference Hurd and Zimmerman2014), and providing youth workers within offline and online communities. However, for such interventions to be effective, it will likely be important to provide children with the information and social skills required to access these potential sources of support and be able to build healthy interpersonal relationships (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Stevens, Purtscheller, Knapp, Fonagy, Evans-Lacko and Paul2021). This underscores the importance of implementing interventions at multiple levels because individual-, family- and community-level factors interact with each other (García-Carrión et al., Reference García-Carrión, Villarejo-Carballido and Villardón-Gallego2019; Ungar and Theron, Reference Ungar and Theron2020). Second, the protective factors examined in our study were not specific to the population of poly-victimised children. Our findings therefore lend support to universally implemented interventions. However, these interventions can be costly, and the resources required for implementation are limited. We therefore recommend prioritising poly-victimised children first, given their higher levels of psychopathology compared to non-poly-victimised children, and prioritising individually targeted interventions over collective interventions. Furthermore, these interventions need to be evaluated before widespread implementation, taking into account unintended negative consequences associated with these prevention programmes, such as stigmatisation or increased stress (Durlak and Wells, Reference Durlak and Wells1998).

Conclusion

Having at least one supportive adult was found to be associated with less psychopathology in early adulthood among both poly-victimised and non-poly-victimised children. Therefore, these findings suggest that mental health promotion strategies in youth should promote better availability and utilisation of supportive adults during childhood and be implemented universally. However, further research is needed with contemporary samples and in other contexts to replicate our findings. Moreover, future studies should investigate the effectiveness of interventions to prevent mental health difficulties that target poly-victimised children, given the higher burden of psychopathology that they experience in early adulthood.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796024000660.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset reported in the current article is not publicly available due to lack of informed consent and ethical approval for open access, but is available on request by qualified scientists. Requests require a concept paper describing the purpose of data access, ethical approval at the applicant’s institution, and provision for secure data access (for further details, see here: https://eriskstudy.com/data-access/). Supporting Stata code will become publicly available via F.B.’s GitHub account on publication: https://github.com/FloraBlangis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study mothers and fathers, the twins, and the twins’ teachers and neighbours for their participation. Our thanks to CACI, Inc., and to members of the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work and insights.

Financial support

The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Study is funded by grants from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) (grant numbers G1002190, MR/X010791/1). Additional support was provided by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number HD077482) and the Jacobs Foundation. HLF and RML were supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Centre for Society and Mental Health at King’s College London (grant number ES/S012567/1). For the purpose of Open Access, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC or King’s College London.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.