Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Hammad et al. Reference Hammad, Laughren and Racoosin2006; Hetrick et al. Reference Hetrick, Mckenzie, Cox, Simmons and Merry2012; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Guski, Freund and Gotzsche2016) and observational studies (Barbui et al. Reference Barbui, Esposito and Cipriani2009) suggest that antidepressants may increase the suicide risk in youth, which justifies the decision of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue a black box warning. Contesting that controversial decision, some authors used ecological data to allegedly show that there was an increase in suicide risk after the introduction of the FDA warning in 2004 (e.g. Gibbons et al. Reference Gibbons, Brown, Hur, Marcus, Bhaumik, Erkens, Herings and Mann2007). However, that specific study in question and some other research were criticised for being severely flawed (Stone, Reference Stone2014) and surprisingly, there are no recent replications of these critical studies. In particular, to avoid biases owing to random fluctuations in suicide attempt rates during short-time intervals, long observation periods are necessary. Therefore, here we focus on antidepressant prescriptions and suicide attempt rates from 2004 to 2016 in adolescents aged 12–17 years.

Method

Our analysis is based on the public use data from the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) extracted from http://pdas.samhsa.gov. The NSDUH is a nationally representative survey among the civilian, non-instutionalised US population. Data were assessed by interviewers during in-person visits to households and non-institutional group quarters (detailed information online https://www.samhsa.gov/data/population-data-nsduh/reports). If participants screened positive on gate questions on depressed mood, they were asked nine specific symptoms of depression and were categorised as having past year major depression if they had at least five depression symptoms several days or longer in the past year (see, for example, Appendix F in the 2016 codebook). Participants were also asked if they took prescribed medication for their mood problems in the past year. No more details were given about the specific medication, but since prescriptions for mood problems are most likely antidepressants, we used this variable as a proxy for antidepressant medication. Participants who screened positive on the gate questions were also asked specific items on suicidality, from suicide ideation to suicide attempts. The item on suicide attempt was ‘Did you make a suicide attempt or try to kill yourself?’ No information on the specific timing of the suicide attempt was given. However, this suicide attempt variable seemed to be valid of actual past year suicide risk, since it correlated high and significant with the yearly suicide rates of the same age group, r = 0.75, 95% CI 0.33–0.92 (yearly suicide rates retrieved from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html). We cross-tabulated the relevant variables for each year, using the survey package in R and a validated R-code to account for the complex sampling design. Pearson correlations were used to quantify associations between variables. The R-code and the extracted data can be obtained upon request from the authors.

Results

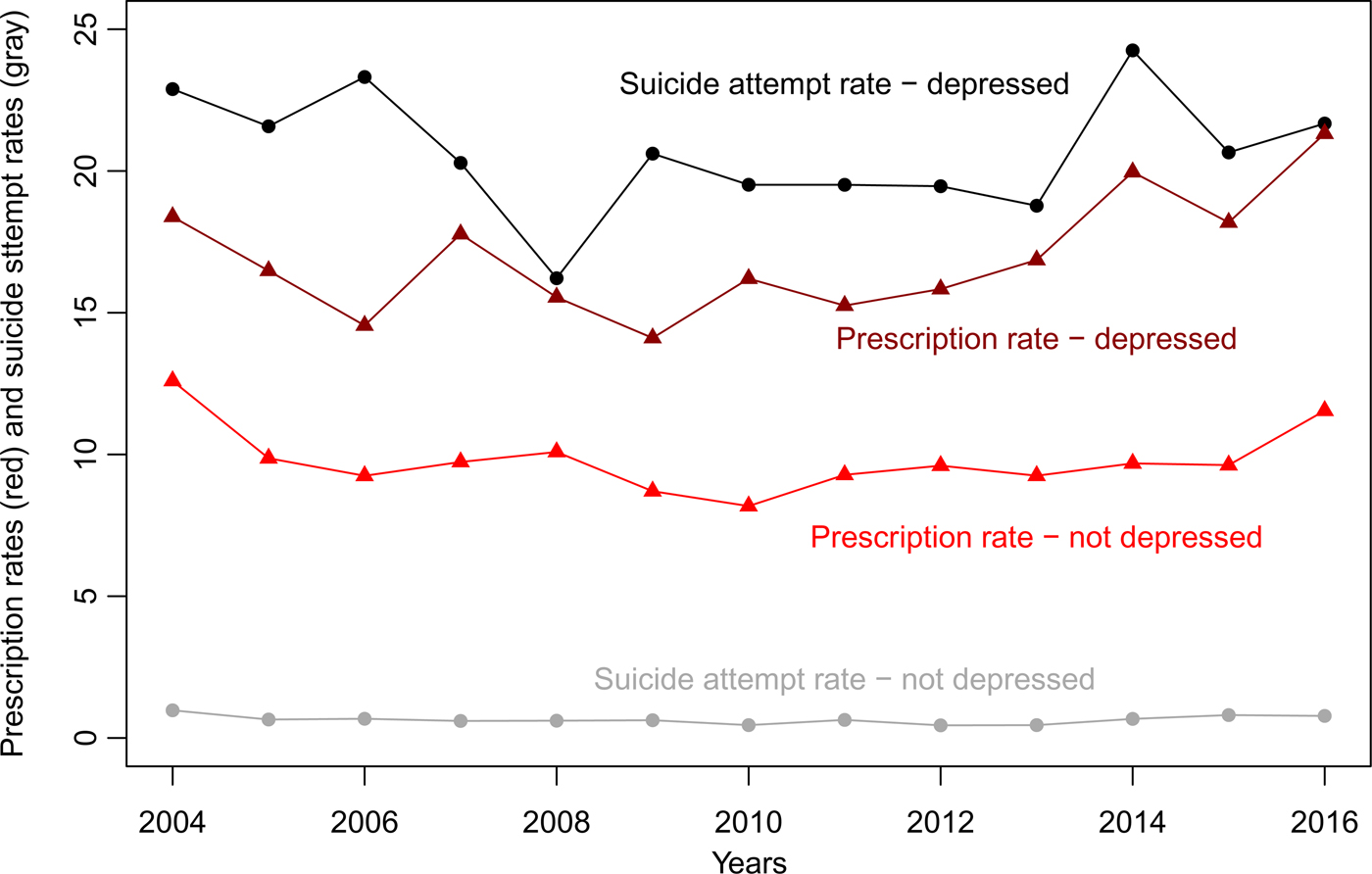

Figure 1 shows the rate of suicide attempts and self-reported prescriptions for mood disorders (most likely antidepressants) for persons with and without major depression (MD). Both prescription and suicide attempt rates decreased after the FDA warning in 2004 but increased in recent years. If antidepressants cause suicidality, then the reversal of the prescription trend should precede the reversal of the suicidality trend. This was confirmed with a Buishand U-Test that revealed a changepoint for antidepressants rates most likely at 2012 (U = 0.41, p = 0.05) and for suicide attempt rates most likely in 2013 (U = 0.45, p < 0.05). The correlation between suicide attempt rates and prescription rates was r = 0.83 (95% CI 0.51–0.95; p < 0.01) for all adolescents, r = 0.41 (−0.18–0.78; p = 0.16) for those with MD, and r = 0.76 (0.37–0.93; p < 0.01) for those without MD.

Fig. 1. Suicide attempt and antidepressant prescription rates in adolescents aged 12–17 years with and without major depression.

Discussion

Suicidality is a core feature of MD, and MD is commonly treated with antidepressants, hence producing at least in part a spurious correlation. However, persons without MD are rarely suicidal, therefore, in these youths, the strong correlation between suicide attempts and antidepressant prescriptions is hardly explained by indication alone. Also, antidepressant prescription rates increased before the suicide attempt rates, which accords to individual person data demonstrating that the suicide risk is highest after initiation of antidepressant pharmacotherapy (Bjorkenstam et al. Reference Bjorkenstam, Moller, Ringback, Salmi, Hallqvist and Ljung2013). This is an important finding because temporality is a necessary but not sufficient prerequisite for causality (Hill, Reference Hill1965). Additional research has revealed that the antidepressant-suicidality association is most likely dose-dependent (Courtet et al. Reference Courtet, Lopez-Castroman, Jaussent and Gorwood2014; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Swanson, Azrael, Pate and Sturmer2014), which is another key aspect of causality (Hill, Reference Hill1965).

Our study is limited because we could not determine the exact medication and the exact time of the suicide attempt. Moreover, all data relied on self-reports, which may bias estimates of both suicide attempts and antidepressant prescriptions. However, in line with the meta-analytic evidence from RCTs (Hammad et al. Reference Hammad, Laughren and Racoosin2006; Hetrick et al. Reference Hetrick, Mckenzie, Cox, Simmons and Merry2012; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Guski, Freund and Gotzsche2016), one interpretation of our findings is that antidepressants may cause suicidality in some adolescents.

Efforts to deliver mental health care for adolescents and young adults are of highest public health significance to reduce the suicide risk, but we want to caution against the indiscriminate use of antidepressant drugs, which may worsen the problem they are supposed to treat. Based on our findings we stress that the FDA's decision to issue a black box warning was justified and necessary.

Acknowledgements

Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this publication. We thank Anthony Damico for providing R-code to use the NSDUH data https://github.com/abresler/usgsd/blob/master/National%20Survey%20on%20Drug%20Use%20and%20Health/replicate%20samhsa%20puf.R

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Availability of data and materials

The R-code is available upon request from the authors. The data are available publicly (see Methods section for link).