The moment when guest workers departed Turkey was one of great rupture – not only for the guest workers themselves but also for the families they left behind. In all corners of Turkey’s vast landscape, from major cities and the Anatolian countryside, the news of West Germany’s urgent need for laborers had spread. Seeking to escape unemployment, gain wealth, or simply have an adventure, hundreds of thousands of young men and women flocked to the West German government’s recruitment offices. The largest one was in Istanbul, where 200,000 prospective workers applied each week.Footnote 1 Weary and hopeful, they filled out extensive paperwork, underwent humiliating medical examinations, and waited seemingly interminably for the result. Would they be accepted? Or would they be rejected on the grounds that they were too young, old, sickly, or disabled? Especially for those from rural Anatolia, the stakes of rejection were high. Having “scrambled together” thousands of lira, or even sold their fields and animals to afford the two-day car or bus ride to Istanbul, they feared returning empty-handed, to be greeted with disdain, disappointment, and a loss of prestige. “Not passing would have been a catastrophe for us,” one guest worker explained years later. “Those who did not pass cried like children.” They considered it a “matter of honor” and “did not have the courage to return to their villages.”Footnote 2

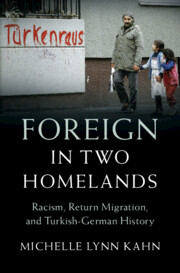

For those who survived the arduous recruitment process, then came the scene of departure, full of tearful goodbyes at Istanbul’s Sirkeci Train Station (Figure 1.1). Friends, parents, aunts, uncles, spouses, and children all crowded together, reaching over the wooden gates for one last hug and kiss. “We’ll miss you! Send us a color photo from Germany!” they shouted.Footnote 3 Only those from Istanbul enjoyed the luxury of being present on the platform. Others, from all throughout the vast country, had already said their goodbyes. As the train door shut, they strained their necks to look upward at the windows, catching a final glimpse before the departure. Some embarking on the journey waved excitedly back, while others stared wistfully into the distance, wondering if they would soon regret their decision. The stay in Germany was only supposed to last two years, but neither the guest workers nor their loved ones knew when they would be reunited. They hoped that the happy day would come soon.

Figure 1.1 With mixed emotions, family members watch guest workers depart for Germany at Istanbul’s Sirkeci Train Station, 1964.

Migration, as this chapter shows, was not only an individual experience but also a familial and communal one. Guest workers’ departure fundamentally disrupted the lives of the family members, neighbors, and friends they left behind. Economically, it drained village economies of able-bodied young men and women, leading to gendered and generational shifts in the division of labor that created new burdens and opportunities. It was the social destabilization, however, that left the most lasting mark on Turkish attitudes toward the guest worker program. Although parents and spouses often encouraged guest workers to travel abroad, tensions emerged due to conflicts between expectations and reality: whether guest workers were sending enough money home, writing enough letters to their loved ones, or – crucially – returning frequently enough (or at all). As time passed, and as emotional distance grew to match physical distance, the perceived abandonment of the family came to represent the abandonment of the nation.

Not all families shared the same experiences, of course, and the perception of abandoned families changed over time. During the formal recruitment years of 1961 to 1973, most guest workers traveled to West Germany alone, leaving husbands, wives, children, and parents behind. Guest workers’ spouses and children did not begin migrating in large numbers until after the 1973 recruitment stop, strategically navigating West Germany’s lax (though complex) policy of family reunification.Footnote 4 But even during the 1970s, not all families reunified. Some who reunified did not reunify entirely, and others moved back and forth between the two countries as “suitcase children” (Kofferkinder) in a seemingly perpetual state of transience.

Despite efforts to overcome the physical distance, fears of abandonment were inescapable on both sides. Struggling with homesickness and living in isolated factory dormitories, guest workers developed multiple strategies to avoid isolation and maintain contact with home. But letters, phone calls, and even cassette recordings of their voices were not enough, and families struggled to adapt to the absence of a husband, wife, parent, child, or breadwinner. Rumors reverberated in the echo chamber of village chatter, newspapers, films, and folklore. Bombarded with horror stories about male guest workers lavishing themselves in West Germany’s sexually promiscuous culture, wives grew increasingly concerned about their husbands’ whereabouts. They worried that guest workers were running off with blonde German women, and fears of adultery spread. Children left behind in villages with grandparents or shuttled between the two countries became viewed as orphaned and uprooted victims of parental neglect, while those born in Germany, or whose parents brought them there amid the family reunifications of the 1970s, were seen as caught between two cultures, unable to speak the Turkish language, and dressing and behaving like Germans. These concerns, despite emerging within families and local communities in Turkey, spread throughout both countries and became frequent themes in news reports, novels, and films.

In West Germany, guest workers’ family relations and sexualities were crucial to their racialization. Guest workers’ arrival in the 1960s and early 1970s coincided with West Germany’s sexual revolution, a time when concerns about promiscuity, immorality, and the breakup of the family pervaded German public discourse. As Lauren Stokes has shown, Germans condemned the “Mediterranean family,” “Southern family,” and “foreign family” as a backward and oppressive institution that allegedly clashed with West Germany’s self-definition as a liberal democracy.Footnote 5 Guest workers’ sex with German women also dominated headlines, perpetuating stereotypes of violence, patriarchy, and the transgression of national and racial borders. When Turks became the largest ethnic minority in the late 1970s, feminists in the nascent German women’s movement increasingly applied these racializing tropes to the “Turkish family” or “Muslim family” as a litmus test for their inability to integrate.Footnote 6 In both countries, therefore, concerns about the family became enduring tropes in the migrants’ sense of dual estrangement.

Coping with Homesickness

Of all the hardships guest workers faced in Germany, from the backbreaking work in factories and mines to the everyday discrimination by Germans, homesickness and fears of abandonment were among the harshest. Would their parents, husbands, and wives cry every night missing them? Would their young children be able to recognize them upon their return? How would they stay connected to their families at home, and to their homeland as a whole? Where would they get news from Turkey? How could they start new lives without abandoning – or feeling abandoned by – home? To quell these anxieties, guest workers developed numerous strategies – from sending letters, postcards, and photographs, to making friends with other Turks who functioned as surrogate families and support systems, to decorating their bedrooms with Turkish half-moon flags and other nationalist symbols. All worked to ease, but never cure, the pangs of homesickness, and to compress, but never fully close, the growing emotional distance.

These anxieties began even before guest workers set foot in Germany, on the initial train ride.Footnote 7 Not only did the trains lack food, water, and adequate seating (with one West German transportation planner admitting that they were “unacceptable from a humanitarian perspective”), but the idle time also forced guest workers to process their emotions.Footnote 8 The Turkish singer Ferdi Tayfur captured these emotions in his renowned 1977 arabesque ballad “Almanya Treni” (Germany Train). As his train leaves the platform, the singer is overwhelmed with sweet memories of time spent at home with his lover, from whom he will now be separated by thousands of miles. “Do not cry, do not hurt, my rose,” he comforts her, imploring her to remain faithful. “Germany is very far,” he sings. “Do not abandon me. Do not leave me in Germany without a letter.”Footnote 9

One former guest worker, Filiz, explained that the reactions of the women on her train varied based on marital and maternal status. While the younger, single women delighted in imagining the exciting life that awaited them abroad, the wives and mothers of the group appeared “mournful.” One woman “wailed and wept” because she had left her three children behind.Footnote 10 Displays of sadness were so common that one departing woman, Cemile, felt excluded from the collective experience. Assuming that she would cry upon her departure, her brother-in-law had given her a pill that would supposedly subdue her tears. In reality, as she remarked years later, she was not sad at all, because departing her village “freed” her from her despised mother-in-law, who had “oppressed and bullied” her. To bond with her fellow passengers, she performed the expected emotion of sadness by smearing spit into her eye and pretending to cry.Footnote 11

These reactions reflect the wide variance in guest workers’ relationships to their families. A 1964 study reported that 56 percent of all Turkish workers in Germany were married, while a Turkish State Planning Organization report ten years later showed that the number had climbed to 80 percent.Footnote 12 This increase reflected the West German government’s evolving recruitment strategy, which first centered on cities with higher numbers of single young adults but later expanded to rural regions with higher marriage rates.Footnote 13 While some married migrants appreciated the liberation from overbearing in-laws or abusive spouses, they were overall more likely to mourn the distance from their families, especially if they had young children. Single men and women, on the other hand, missed their parents, siblings, and lovers, but tended to be more willing to embrace Germany as an exciting opportunity. For rural women, as sociologist Nermin Abadan-Unat has explained, migration resulted in a “pseudo-emancipation,” offering them the chance to escape gender constraints and develop new power over family spending and decision-making.Footnote 14

But no matter how excited, sorrowful, or bittersweet they felt, homesickness and fears of abandonment loomed large, and employers, organizations, and the West German and Turkish governments sought to ease the difficult transition to life abroad. In 1963, the Workers’ Welfare Organization (Arbeiterwohlfahrt, AWO) in Cologne established a Center for Turkish Workers, nicknamed the “Turkish library,” which featured daily Turkish newspapers and books sent by the Turkish Ministry of Culture. While enjoying Turkish coffee or tea, guest workers could chat about gossip from home, watch Turkish films, and play table tennis in the basement recreation room. Reflecting the importance of the center to the Turkish government, Ambassador Mehmet Baydur presented the workers with a gift emblematic of national pride: a bust of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. Appreciating the comfort and community, one guest worker who attended the opening called Cologne his “second homeland.”Footnote 15 Yet the Center was exceptional, as cultural venues in most cities and smaller towns were slim to none.

Employers, too, sometimes created spaces to accommodate Turkish workers. The focus was on their Muslim faith, which West Germans considered the most significant marker of cultural difference. Management at the Sterkrade coalmine in Oberhausen, which in the early 1960s employed primarily Turkish workers, boasted that their dining halls never served pork and that their facility featured a prayer room with a rug facing Mecca.Footnote 16 Others came up with creative solutions. The Hanover branch of the German Federal Railways turned two empty train cars into makeshift prayer rooms, which guest workers affectionately called “mobile mosques” or “mosques on wheels.”Footnote 17 As in the case of cultural centers, however, the provision of prayer rooms was a rarity. A 1971 study revealed that only 8 percent of firms with predominantly Turkish workers in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia offered prayer rooms.Footnote 18

Absent designated spaces, guest workers created their own. Local train stations, so characteristic of guest workers’ transient experiences, soon became among their most frequent meeting points. The eleventh platform of the Central Train Station in Munich, where most guest workers had first arrived in Germany, held special nostalgia, with Mahir, one of the earliest Turks to come to Germany, calling it the “gate to the homeland” (Tor zur Heimat).Footnote 19 On their days off each Sunday and on Christian holidays, dozens of usually male Turkish workers congregated in the station’s halls, reading newspapers aloud, catching up on Turkish politics, and sharing advice on how to solve conflicts with German employers (Figure 1.2).Footnote 20 These gatherings, however, made Germans uneasy. Repeating unfounded tropes of Turkish men’s criminality, one German newspaper asked in 1972: “The guest workers in the Munich Central Train Station – are they really so dangerous or do they only look like it?”Footnote 21 With few exceptions, however, guest workers were not engaging in crime and would have preferred to meet elsewhere. But, at a time before the proliferation of Turkish coffee houses opened by guest workers seeking self-sufficiency, train stations were a last resort. Back then, Mahir explained, “We had no other places.”Footnote 22

Figure 1.2 Guest workers read the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet at a train station in Hanover, 1974.

In the private sphere, as Jennifer Miller and Sarah Thomsen Vierra have illuminated, no space was as central to guest workers’ lives as their factory dormitories.Footnote 23 Before the 1973 recruitment stop and rise in family migration, housing guest workers collectively in dormitories was not only an efficient and cost-effective way for firms to keep workers close to their jobs but also a means of social control. These dormitories accommodated mostly Turkish workers but were also home to guest workers from other countries that had signed labor recruitment agreements with the Federal Republic. With all guest workers residing in the same location, factory personnel could monitor their whereabouts and ensure that their focus was, in fact, their work. The carefully crafted dynamics of the dormitories ensured that social interactions typically occurred along gender and national lines. Men and women lived in separate buildings, and workers of the same nationality shared rooms. Those seeking to interact with local Germans or other guest workers of the opposite gender generally had to venture outside their residences. Segregating guest workers in these dormitories had the lasting effect of impeding their social interactions with Germans from the very beginning, serving as evidence of the West German government’s failure to make efforts to integrate them even though Turks were often blamed for failing to integrate.

The ability to forge friendships in factory dormitories depended not only on gender and nationality but also on the cleavages and prejudices of class, rural versus urban origin, and religiosity. Many guest workers of urban origin – especially those who came from middle-class families in Istanbul and other major cities on the geographically western side of Turkey – considered themselves “modern,” “cosmopolitan,” and “European” and found more commonality with Germans than they did the pejoratively named “village Turks” (Dorftürken) from Anatolia.Footnote 24 Muazzez, who worked at the Blaupunkt factory in Hildesheim, summarized these prejudices and the name-calling among the women in her dormitory: the “modern” women were “prostitutes,” and the “traditional,” “religious” women were “stupid bumpkins.”Footnote 25 Photographs from Polaroid cameras – one of the first purchases guest workers made to document their new lives in West Germany – portray these divides. In some photographs, smiling guest workers drink beer, play cards, watch television, listen to music, and sit on bunk beds – all segregated by gender.Footnote 26 One photograph shows cliques of urban-looking women dressed in accordance with the fashion magazines to which they would have had access in Turkish cities, wearing colorful tank tops, miniskirts, and tight jeans.Footnote 27 Another photograph, however, shows several women wearing headscarves and the long skirts typical of the countryside as they sit on the floor, cleaning their shoes and cracking nuts – activities that the German archive housing these photographs tellingly refers to as “village traditions.”Footnote 28

Beyond everyday social interaction, friendships forged in factory dormitories also served as crucial support networks, or surrogate families, which sustained them in times of crisis or uncertainty. Halil, who worked at a cotton mill in Neuhof along with 230 other Turkish men, explained how his friends supported each other both emotionally and financially. They stood in line to visit sick colleagues in the hospital and even pooled their paychecks when one of them urgently needed to travel to Turkey to care for a sick family member. Even in less dire circumstances, such as when a colleague wanted to purchase a house in Turkey or invest in a Turkish company, they handed him some cash and wished him the best of luck.Footnote 29 By the late 1960s, guest workers institutionalized informal meetings between friends and colleagues into cultural, religious, economic, and political immigrant associations.Footnote 30 And by the 1970s, male guest workers in particular began assuming leadership positions in trade unions.

The downside to the formation of new communities along gender, national, and rural–urban lines was that they often spun into a downward spiral of collective commiseration. Necan, a guest worker at the Siemens factory in Berlin, recalled that she and her roommates tended to discuss only Turkey – or, more specifically, only Istanbul, as many urbanites considered their home city representative of the entire country. “We had no other topic,” she explained. “What else could we have talked about? Economics or politics? The entire topic was our homeland.”Footnote 31 The situation was similar for Nuriye, who left her husband behind in 1965 to work at a factory in Bielefeld. “It was terrible being alone in this foreign country,” she recalled. “At the beginning we sat together every evening, listened to Turkish music, and cried.”Footnote 32

With socializing a powerful yet inadequate antidote, guest workers also quelled their homesickness through material objects, decorating their bedroom walls with items that reminded them of home (Figure 1.3).Footnote 33 These objects were often symbols of nationalism, such as Turkish flags, portraits of political figures (including a popular wall tapestry of Atatürk, in full military garb, standing next to the Turkish flag), images of scenic Turkish landscapes and maps, and even magazine covers depicting famous Turkish wrestlers.Footnote 34 Workers from Turkish cities, where cameras were available for purchase, also adorned their walls with photographs of family members or even pets left behind.Footnote 35 Not all decorations, however, were connected to Turkey. Some male workers hung up photographs of scantily clad women cut out from magazines.Footnote 36

Figure 1.3 Ömer displays his bedroom decorations at his factory dormitory in Hanau, 1966. Among them are the Turkish flag, a portrait of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and scenic images of Turkey – all reminders of home.

Of course, staring wistfully at nationalistic decorations on walls and chatting about the homeland with new Turkish friends were no substitute for communication with loved ones at home. Over the years, guest workers developed multiple strategies for keeping in touch with their families. Not only did they fulfill their financial obligations by sending their families substantial portions of their paychecks, but they also regularly sent (and received) letters, postcards, and even cassette recordings of their voices. Yet communication between the two countries was hindered not only by slow postal systems and letters getting lost in the mail but also by guest workers’ and their families’ varying socioeconomic statuses, literacy rates, and rural versus urban origins. The necessity of relying on other guest workers, or other neighbors in villages, as translators or intermediaries made communication between the two countries not only an individual or intrafamilial but also a communal experience. Even if they did not have relatives working in Germany, friends and neighbors in Turkey, too, heard stories – both real and fabricated – about the migrants’ lives and the riches they had earned. These stories shaped perceptions of guest workers in the homeland and tended to encourage future migration.

Sending money home was the most important factor driving guest workers’ individual decisions to migrate, as well as the Turkish government’s decision to send workers abroad. They did so through remittance payments: one-time cash transfers from their bank accounts in West Germany to their relatives’ accounts in Turkey. Guest workers’ families prized remittances not only for the lump sum itself but also for the substantially higher value of the West German Deutschmark compared to the Turkish lira. In 1961, at the start of the guest worker recruitment, the Deutschmark was worth triple the lira and, ten years later, quadruple.Footnote 37 “I get four liras for one mark,” Hasan explained. “If I send 200 marks home, then the family gets 800 liras for it,” he said, adding that he lived frugally and sent his parents in Istanbul 100–150 DM monthly.Footnote 38

Although guest workers were certainly not living luxuriously, the notion that they had “pockets full of Deutschmarks” shaped Turkish perceptions of them. Family members’ expectations of receiving remittances were no secret. Özgür, the father of a guest worker, repeatedly sent letters from the Turkish coal-mining town Zonguldak to his German daughter-in-law, Charlotte, in Cologne, inquiring about his son’s finances behind his back. “It has been three years since Metin went to Germany,” he wrote in 1964. “Since then, those who went to Germany from Turkey have made big money. How much money does Metin have in the bank now?”Footnote 39 When Charlotte complained about Metin’s excessive spending habits, Özgür suggested that the couple move back to Zonguldak and live with him. Grossly exaggerating the exchange rate, he noted that Deutschmarks were worth twenty-five to thirty lira. “You would not need to pay rent, a kilogram of water costs six lira, and vegetables and fruits are inexpensive.”Footnote 40

As the case of Özgür, Metin, and Charlotte reveals, the other most important forms of communication between the two countries were letters, postcards, and packages. Like the migrants themselves, correspondence from parents, spouses, and children journeyed from Turkey to Germany – but, unlike the guest workers’ three-day train ride, could often take weeks, if not months, to arrive. After waiting seemingly interminably for a response, receiving a letter was such a cause for excitement that guest workers regularly photographed themselves sitting in their dormitory rooms reading mail. In one photograph, Filiz lies on her bed with a pen and paper in hand, likely responding to one of the many postcards she received from her friends and family in Istanbul, which tended to feature landscapes of the city’s most beloved tourist sites, such as the Bosphorus Bridge, the Emirgan Forest, and the neighborhood of Eminönü.Footnote 41 In another, a male guest worker sits at a small side table covered in an embroidered tablecloth (presumably brought from the home country) and opens a letter, while one of his roommates stands beside him, eager to hear any news from home.Footnote 42

In their handwritten letters home, guest workers described their living situations – the good and the bad – and expressed somber emotions of longing and homesickness. In the winter of 1966, a young married couple named Hatice and Zoltan wrote to Zoltan’s parents, airing their grievances. Although they lived on their own rather than in a factory dormitory, their apartment was cramped and cold, and long work hours and minimal contact with locals left them struggling to learn German.Footnote 43 “Despite having seen you four months ago, I miss you now more than ever before,” Zoltan confessed. “I am homesick.”Footnote 44 The couple’s letters also reveal that guest workers’ family members often sent packages in the mail. Hatice asked his parents to send him some wool gloves, long underwear, and cotton briefs from Çift Kaplan, a popular store headquartered in Istanbul. “It is quite cold here,” Hatice wrote, and “things made of cotton are expensive here,” alluding to Turkey’s postwar role as a major exporter of cotton.Footnote 45 Yet packages also carried symbolic meaning. Relics of their homeland, the objects sent in packages were physically touched by Turkish textile workers, purchased at favorite Turkish stores, and packed by their loved ones.

The ability to send letters, however, depended on rural–urban origin, socioeconomic status, and education level. Communicating in writing was the privilege of a few, largely confined to individuals from urban centers or the highest echelons of rural societies. Having grown up and been educated in Istanbul, Hatice and Zoltan wrote well, with the exception of minor grammatical errors. By contrast, guest workers of rural origin left fewer letters in the archives because they and their family members were more likely to be illiterate. When reading letters or newspapers in factory dormitories, guest workers from rural regions regularly relied on social networks, asking their urban counterparts to read and write their letters. Literate neighbors and friends in villages – typically men – performed this act of translation at home.Footnote 46 The communal experience of letter writing meant that knowledge of guest workers’ lives in Germany spread broadly throughout home communities, even among those who did not have relatives abroad.

Telephone communication, too, reflected both Turkey’s rural–urban divide and the communal experience of circulating knowledge about guest workers. In the formal recruitment years of the 1960s and early 1970s, telephone connections were not yet installed in most rural regions of Turkey. But even in large cities, not everyone owned a telephone, and even for those who did, expensive international fees made phone calls to West Germany a rarity, often reserved for special occasions such as birthdays.Footnote 47 Owning a telephone thus imbued a family with not only social status but also a newfound responsibility to serve as an intermediary between guest workers in Germany and their families at home. Fatma, whose family came from a small village near Trabzon, recalled this frequent experience in the 1980s: “Individuals from neighboring villages – or the relatives of those in Germany – would call us and say, ‘We would like to talk to so and so. Is he there?’ And then we set the phone down, ran over, and shouted, ‘Telephone for you!’ and they came over to our house and spoke on the phone, of course.”Footnote 48

To bypass the complications of telephone calls, guest workers and their loved ones at home developed another strategy: sending audio recordings of their voices.Footnote 49 The mechanism was the creative repurposing of battery-operated cassette players, a new technology that guest workers frequently purchased in Germany to listen to Turkish music. The process was complex. After recording their voice messages on a blank tape, the senders located fellow guest workers who were planning to travel home to a neighboring city or village and who would be willing to transport the cassette player, along with some extra blank tapes, to the recipients. After listening to the voice message, the recipients would then record their own responses on the blank tapes and send the cassette player back to Germany through the same or another liaison. As with letters and telephone calls, social networks were crucial to carrying out this process. The Sunday meetings at the train stations, for example, were spaces where cassette players exchanged hands.

Not all guest workers, however, conveyed truthful accounts. Instead, they sometimes performed emotions that they believed were expected of them. Filiz and her long-term best friend Necan admitted that they had staged the happy photographs they had sent to Filiz’s parents in Istanbul. Upon first glance, the photographs show exciting lives filled with music, parties, and window shopping through the streets of West Berlin.Footnote 50 Although they truly enjoyed these experiences, the two women deliberately downplayed their malaise and exhaustion from hard work. To avoid worrying Filiz’s parents, they dressed up in fancy clothing, made their room look nicer than it was – “We even purchased flowers!” – and smiled extra widely.Footnote 51 The staging of these photographs calls into question the veracity of the stories guest workers told to loved ones at home. Other guest workers, too, may have fabricated or exaggerated their quality of life, as well as the wealth they acquired in Germany, to offer reassuring accounts of their happiness and success.

Despite possible fabrications, those in the home country – whether family members, neighbors, friends, or community members – generally took guest workers’ stories at face value and saw within them a glimmer of hope for themselves to forge a better life.Footnote 52 These stories thus served as a pull factor that convinced others to work in Germany via chain migration.Footnote 53 One guest worker named Osman, for example, attributed his migration decision to his uncle, who wrote letters from Germany boasting that “he was full of meat and vegetables every day.”Footnote 54 Osman’s uncle then “invited” him to come to Germany by securing a work permit for him not through the formal channel of the governmental recruitment program, but rather through his employer – a common practice at the time for circumventing the bureaucracy, the seemingly interminable waiting period, and humiliating medical examinations at the official recruitment offices.

Above all, the best antidote to homesickness was the ability to have one’s family in Germany (Figure 1.4). By 1968, already 58 percent of married male guest workers of all nationalities had brought their wives to Germany, typically within one year of their departure. By 1971, over half of the guest workers had brought at least one of their children to Germany. These numbers increased markedly throughout the 1970s upon the surge in family migration, and by 1980 over 90 percent of guest workers moved out of their factory dormitories and into their own apartments.Footnote 55 But eliminating physical distance did not mean that emotional distance disappeared. No amount of money, letters, postcards, or voice recordings could substitute for the absence of a loved one, and even the happiest of reunions after years apart were often tinged with remorse.

Figure 1.4 Members of the Dağdeviren family, who were able to migrate through West Germany’s family reunification policy, smile from their apartment window in Munich, 1969.

Adulterous Husbands and Scorned Wives

Although guest workers generally endeavored to maintain close communication with Turkey, long distances and a slow postal system left many families worrying about the workers’ fates. Nightmare scenarios played out in their heads, fueled by rumors and stereotypes about the unscrupulous behaviors to which guest workers might adapt in a West German society that villagers often imagined as promiscuous and immoral. Sexually charged, gendered, and racialized, these rumors were grounded in true, yet isolated, cases of male workers cheating on their wives with busty, blonde German women – or worse, abandoning their wives and children entirely. These rumors were not confined to men. The imagined sexual proclivities of female guest workers, who were living in Germany alone and were no longer bound to the watchful eye of traditional family structures, became the focus of concern as well. By the mid-1970s, the trope of the sexually promiscuous – or worse, adulterous – guest worker had reached urban milieus and had crystallized into music, film, literature, and other forms of popular culture. By transgressing both family and nation and fueling feelings of abandonment, sex between Turks and Germans was one of the earliest indications that Turks had purportedly “Germanized” and lost their Turkish identity

Even before guest worker migration to Germany, Turkish villagers already associated migration with the vices of urban life. From the 1930s to the 1950s, millions of villagers migrated as seasonal workers to Turkish cities, particularly to Istanbul’s notorious shantytowns (gecekondu), and returned with shocking tales of corruption and sexual depravity.Footnote 56 The perceived immorality of cities threatened the stability of rural gender relations and family life, which were already in flux. Since the 1923 founding of the Turkish Republic under Atatürk, Turkish policymakers had embarked upon a mission to secularize, “modernize,” and “civilize” the countryside, in part by promoting greater autonomy for rural women, whom urbanites viewed as submissive victims of Islamic law.Footnote 57 While these reforms succeeded in improving women’s legal position in relation to their husbands (particularly regarding divorce), customary family structures remained largely in place.Footnote 58 Once women reached adulthood and marriage, they typically wore headscarves, long skirts, and long-sleeved shirts – a far cry from the miniskirts, spaghetti straps, and high heels popular in both German and Turkish cities at the time. Premarital sex, adultery, and promiscuity were serious taboos, and rumors about deviance often spread like wildfire.

More so than internal migration from the Turkish countryside to cities, migration abroad to West Germany posed a special threat to gender and sexual norms. Despite Germany’s own rural–urban divides, Turkish villagers imagined the country (and Western Europe as a whole) as a monolithic urban space – made more fearsome due to religious differences. Villagers feared that guest workers would eat pork, worship in Christian churches, have extramarital sex, and turn into gâvur, the derogatory Turkish word for non-Muslims, which implied that one was an infidel or traitor to the faith.Footnote 59 These concerns were decidedly gendered. Men might eagerly indulge in the seedy yet tantalizing offerings of the underbelly of German cities, such as bars, brothels, prostitution, and late-night hookups.Footnote 60 Women wandering alone and unprotected in German cities might provoke unwanted sexual attention. “As soon as you get off the train, German men will kiss you!” one woman was warned.Footnote 61 “Thank God!” she recalled years later, “No one kissed us, and no one tried to make a pass at us.” So, too, were these discourses overwhelmingly heteronormative. Sources testifying to homosexuality among guest workers in the early 1960s, particularly those produced by guest workers themselves or those in their home country, are comparably scant – reflective largely of the stigmatization and silences surrounding homosexuality at the time.Footnote 62

Although villagers’ concerns predated guest worker migration, they were amplified amid vast transformations in gender and sexuality within West Germany itself. Germany’s loss in 1945 represented a national emasculation, whereby German men – prized for their strength and vigor during the Third Reich – experienced a collective crisis of masculinity.Footnote 63 Moreover, in 1961, the same year that Turkish guest workers first began arriving in Germany, the contraceptive pill burst onto German markets, giving women newfound control over their bodies and reproductive choices and ushering in the sexual revolution, second-wave feminism, and gay liberation movements.Footnote 64 Despite this transformation of sexuality in the public sphere, the 1950s conservative emphasis on the stability of the family did not disappear, and many Germans, particularly the aging postwar generation, associated promiscuity and pornography with the moral corruption of youth and, by proxy, of the nation.Footnote 65 Contestations over gender and sexuality impacted Germans’ and Turks’ attitudes about each other, becoming a litmus test for cultural compatibility. By the late 1970s, as Rita Chin has shown, white mainstream West German feminists committed to the emancipatory potential of sexuality inadvertently fueled racism by decrying Turkish and Muslim gender relations as “backward,” “patriarchal,” and incompatible with a post-fascist and Cold War society that defined itself as liberal, democratic, and free.Footnote 66 Moreover, German women’s decisions to have sex with Turkish men rather than (or in addition to) German men enflamed preexisting tensions about “race-mixing” (Rassenschande) and contributed to German men’s crisis of masculinity.Footnote 67

Sex across borders had a racialized component (Figure 1.5). German women’s blonde hair and blue eyes were repeatedly mentioned in Turkish newspapers, folklore, and films from the 1960s through the 1980s, while Germans reiterated Orientalist tropes by racializing migrants from the Mediterranean and the Middle East as “dark-skinned” and “exotic.” Even in the 1980s, West German feminists invoked this racialized view as they struggled to wrap their heads around what they perceived as the curious phenomenon of sex across borders. “Why do Arab men love blonde women and German men love black women? Is it the exoticism, the dark skin, the erotic voice, the swaying gait, or are they simply more charming, natural, sensual, more of a man, more of a woman? Is it the other language, the simultaneously different emotions or caresses that hide within them?” Perhaps, they wondered, the “search for the unknown” was a projection of one’s inner psychological struggles – “an attempt to break through one’s own cultural limitations or imaginative horizon, to intellectually and emotionally conquer something new for oneself?”Footnote 68

Figure 1.5 Male guest workers walk past a blonde German woman with a short skirt upon their arrival in Dortmund, 1964.

Beyond the transnational discourses, concerns about sex were central to guest workers’ everyday lives. Alongside homesickness and isolation, male guest workers often complained about sexual malaise, with one man calling himself “psychologically ill” due to the lack of physical and emotional intimacy.Footnote 69 Another young guest worker was so starved for sex that he admitted having to restrain himself from touching a German woman on a streetcar, confessing that she was so “beautiful” and “free” and “smell[ed] so good.”Footnote 70 Married guest workers were further constrained by their vows, as well as Turkish law, which expressly forbid adultery. Not until the rise of family reunification in the 1970s, when guest workers increasingly brought their spouses to Germany, could they have sex within marriage on a regular basis. If a guest worker alone in Germany wished to have sex with their spouse, they would have to wait until they traveled back to Turkey on vacation, which usually took place just once per year. In 1975, a Turkish midwife in the small village of Çalapverdi explained that the ability to have sex only during their summer vacations drastically impacted birthrates in guest workers’ home villages: while the village typically had only one or two births per months, about thirty women expected babies during the month of March, which was precisely nine months after vacationing guest workers returned to the village in July.Footnote 71

For single guest workers, the lack of sexual gratification owed in many respects to employers’ restrictions on their private lives. As dormitory personnel restricted visitors, especially overnight guests, guest workers seeking satisfaction needed to leave their dormitories.Footnote 72 Female guest workers recalled that their male counterparts often waited outside their dormitories, hoping to take them out on dates.Footnote 73 Frequently, groups of male guest workers also went out on the town to meet German women at bars. Certainly, not all guest workers were interested in German women. Searching for love, a thirty-three-year-old car mechanic who had been living in West Berlin for three years placed a personal advertisement in Anadolu Gazetesi, a newspaper produced by the Turkish government for guest workers: “I have not warmed up to German girls. I prefer Turkish girls,” he wrote, describing himself as 1.7 meters tall, 72 kilograms, with auburn hair, hazel eyes, and even his own apartment (a rarity for a guest worker at the time).Footnote 74 But to his dismay, his dating pool, so to speak, was limited, as male guest workers far outnumbered female guest workers.

Largely due to the racialization of Turks, male guest workers’ attempts to meet German women, either for one-time sexual encounters or long-term romance, often proved frustrating. One guest worker insisted that German women “run after the Italians and Spaniards, and even the Greeks, but … say that they are afraid of us Turks” and “do not want anything to do with us.”Footnote 75 The popular Turkish folkloric singer Ankaralı Turgut captured this frustration in his hit song “Alman Kızları” (German Girls), in which the narrator fantasizes about young German women with “blonde hair” who go out to bars to “chase love” with “handsome young men.” “Turks cannot live without you German girls,” he admits, but laments that they “do not like migrants because they are Turkish.”Footnote 76

German women’s distaste for Turkish men stemmed partly from the sensationalist media coverage of guest workers’ criminality and sexual violence.Footnote 77 As early as the 1960s, German media warned against the wildly tempting “Mediterranean temperament” of dark-skinned, dark-haired men – a racialized category that included not only Turkish but also Italian, Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, and Moroccan guest workers – which allegedly made them prone to violating defenseless German women.Footnote 78 A Hamburg news report on a Turkish guest worker who had strangled his German wife included a remark from a male neighbor, who boasted, “If Helga were mine, she would still be alive.”Footnote 79 Concerns about Turkish men as hypermasculine, virile, and dangerous also regurgitated centuries-long Orientalist tropes about polygamous orgies in the harems of the Ottoman Empire. The same newspaper denounced a Turkish man for entering a local bar with eight headscarf-clad belly dancers and threatening the German owner. Although the real threat was the owner – who had drunk “at least thirty whiskeys” and pulled out a pistol from behind the bar – the newspaper blamed “the Mohammedan,” or “the man from the Orient.”Footnote 80

When a German woman did accept a guest worker’s invitation for a night out on the town, the awkwardness of the first date was often compounded by racist prejudices and logistical issues. Osman Gürlük recounted a horrible series of dates he had with a seventeen-year-old German girl soon after arriving in Dortmund to work as a railroad constructor.Footnote 81 Osman was nervous for the date even before he arrived, since he had no car and “German girls are not interested in men without cars.” But the real problems started as soon as they arrived at the movie theater for their first date, when the girl began disparaging his minimal German language skills. After a few dates, when the girl invited him home, her parents made it clear that “they did not want a Turk.” Unable to have sex at her parents’ house because the girl worried that she would moan too loudly, they were left with limited options. Osman did not have the privacy of a car, and sneaking her into his factory dormitory would have been too risky, since the dormitory personnel were always keeping watch – not to mention that he slept in a bunkbed with multiple other guest workers in the room. After searching around the city for a dark alley, the couple finally had sex – but the relationship ended soon thereafter.

Confirming the fears that circulated throughout Turkish villages, male guest workers sometimes did in fact resort to brothels. The Italian author and literary scholar Gino Chiellino, who lived in Germany and studied migrants’ experiences, expressed guest workers’ mixed feelings about cheating on their wives with prostitutes in a poem aptly titled “Loyalty.”Footnote 82 Yearning sexually for his wife thousands of kilometers away, the poem’s narrator visits a prostitute. He justifies this “dangerous breaking of the vow” by envisioning his wife cheating on him as well. Surely, he wonders, his wife must also feel “horny” (geil), as men in the village gaze at her licentiously during his absence. Having sex with random German women, however, could also lead to troubling encounters. Rumors circulated about unscrupulous German women who got guest workers drunk and stole their money. In one retelling of this tragic fate, a Turkish guest worker picked up a German woman at a bar and took her to a hotel. When he awoke with a hangover despite only drinking two glasses of schnapps, all his money was missing. “We made fun of him,” one of his colleagues recalled. “He was furious at the German girl, and he told us they were all trash.”Footnote 83

Amid the Cold War context, as Jennifer Miller has revealed, male Turkish guest workers also crossed the border into East Germany to meet, have sex with, and even marry East German women.Footnote 84 These intimate relationships across the inter-German border represented a paradox: while West Germans viewed Turks as “eastern,” East Germans viewed them as representatives of the “West.” One Turkish man recalled that East German women dancing in nightclubs viewed Turks as sexually virile and were easily tantalized by the gifts they brought from West Berlin. These relationships, however, brought Turks under state surveillance, as the East German secret police (Stasi) suspected that they were Western spies attempting to subvert the state.Footnote 85

Popular culture in both West Germany and Turkey captured anxieties about sex across borders. In German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s acclaimed 1974 film Angst essen Seele auf (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul), a German widow is ostracized, and even called a “whore” by her grown children, for falling in love with a dashing young Moroccan guest worker. The Turkish film Almanyalı Yarim (My German Lover), released the same year, tells a similarly tragic story of a Turkish guest worker and a wealthy blonde German woman named Maria (portrayed by a Turkish actress), who infuriates her father – a former German military officer during World War II – by moving to Turkey, converting to Islam, and changing her name to the Turkish “Meral.” Like Fassbinder’s, this film uses the trope of female victimization to critique anti-Turkish racism in Germany and – through the father’s portrayal as an unrepentant Nazi – exposes the persistence of racialized thinking well after the fall of Nazism.

Though exaggerated in films, German women did face prejudices for engaging in relationships, and marriages, with Turkish men. In 1972, the Association for German Women Married to Foreigners (Interessengemeinschaft der mit Ausländern verheirateten Frauen, IAF) was formed to fight against their social and legal discrimination. Although the organization was originally founded by educated women married to foreign students, it expanded to include women married to guest workers. On an everyday level, the organization provided a forum for German women to raise consciousness, share their stories, and feel solidarity.Footnote 86 Within ten years, the IAF grew its membership to 28,000, became affiliated with the United Nations and the European Economic Community, and established partnerships with cities throughout the world. Yet the IAF, like many white feminist organizations at the time, was not immune from criticism for inadvertently perpetuating racism. Men affiliated with the IAF complained that the women were seeking to transform their “exotic” husbands into “regular German” men, and when the IAF finally began rallying on behalf of migrant women, their emphasis on migrant women’s victimization at the hands of their excessively patriarchal husbands reinforced racialized stereotypes about the dangerous male foreigners.Footnote 87

The West German government, too, worried about binational relationships. Some foreigners, especially following the 1973 moratorium on guest worker recruitment, engaged in fake marriages (Scheinehen) with German women to secure work and residency permits. In the late 1970s, the West German government threatened to deport a man who had divorced his Turkish wife, married a German woman to secure residency status, divorced the German wife, and married another Turkish woman.Footnote 88 Following Turkey’s September 12, 1980, military coup, fake marriages became entangled with concerns about fake asylum seekers (Scheinasylanten). The state government of West Berlin, for example, blamed the surprising tripling of Turkish-German marriages on the asylum crisis, which officials in turn attributed to underground fake marriage syndicates. Officials were particularly alarmed by an outlying case in which an eighteen-year-old Turkish man married an eighty-two-year-old German woman.Footnote 89

In Turkey, reactions to sex and marriage across borders were likewise complex. Some Turkish parents were delighted to know that their sons had found love abroad. Such was the case with Charlotte and Metin, whose father, Özgür, regularly inquired about his finances. When Metin wrote to his parents in Zonguldak informing them of his intention to marry Charlotte, Özgür gave the couple his enthusiastic blessing in a letter addressed directly to Charlotte.Footnote 90 “Our son is single,” Özgür wrote. “We would like [him] to marry a good German girl,” and “You bring our son much happiness.” Özgür implored the couple to “get engaged in Germany, but marry in TURKEY,” writing in capital letters for emphasis. By signing the letter with “best wishes from us, your parents,” he welcomed Charlotte into the family even before the couple’s engagement.Footnote 91

Unlike West German news outlets, Turkish newspapers of the 1960s often portrayed binational marriages positively, using them to espouse nationalist narratives in which “young and beautiful” German girls cherished their Muslim Turkish husbands.Footnote 92 Yet within Turkish media discourse, wives’ conversion to Islam was crucial.Footnote 93 During the 1960s, Milliyet published countless two-sentence reports often headlined “A German Woman Has Become a Muslim” that specified the woman’s age, maiden name, and new surname.Footnote 94 Entire columns were devoted to especially intriguing cases. In 1964, a German woman was allegedly thrown out of the Catholic Church for her decision to marry her Muslim boyfriend, and the couple encountered difficulty finding a mosque and imam willing to perform their engagement ceremony until she converted to Islam and expressed her excitement for reading a German translation of the Koran.Footnote 95 By enthusiastically embracing Islam, German women could defy national boundaries and say with pride: “Now I, too, am a Turk.”Footnote 96 The possibility that German women might be included in the Turkish national community, at least as implied in the Turkish urban press of the 1960s, stood in stark contrast to Germans’ overwhelmingly racist hostility toward Turkish-German marriages.

The reception of sex across borders differed entirely, however, when it involved the adulterous affairs of guest workers who were already married. Adultery was by far the most pernicious threat involving guest workers’ sexuality and, while overwhelmingly fabricated, rumors circulated widely. A woman from Bolu who later joined her husband in Hanover summarized the wives’ “anxious and uneasy feelings” upon their husbands’ departure: “We heard rumors that Turkish men would marry other wives here, without being divorced.”Footnote 97 To a certain extent, these rumors were true. Lamenting his sexual frustration in the factory dormitory, one man estimated (likely an exaggeration) that 60 percent of his fellow guest workers cheated on their wives.Footnote 98 Frequent reports in Turkish newspapers in the 1960s supported these fears: a Munich judge had “permitted a harem” by allowing a guest worker to legally marry a German woman without divorcing the Turkish wife that he left behind; another migrant had married a German woman and left his four children at home.Footnote 99 In such cases, many abandoned wives in the countryside lived as “married widows,” perpetually mourning the loss of their husbands and enduring ostracization.Footnote 100

In rare situations, adulterous male guest workers brought their new German wives back to their Turkish villages, even though Turkey had criminalized polygamy fifty years prior. A West German magazine reported on the disturbing case of Ali Yalçın who had returned to his Turkish wife and children with his new “blonde wife,” Erika, in tow.Footnote 101 Immediately upon arriving, Erika laid down in their marital bed and demanded that Ali’s Turkish wife serve her breakfast. The drama lasted only several days, however, until Erika realized that Ali had blatantly lied to her about the village’s amenities. Furious that the village had neither electricity nor a hair salon, Erika stormed out of the house and traveled back to Germany, leaving Ali with a broken heart.

In at least one case, adultery occurred across the Iron Curtain. In 1980, a Turkish guest worker living in West Berlin appealed directly to West German Prime Minister Willy Brandt for help in a tricky situation. Two years before, he had divorced his wife in Turkey and – with the permission of East German authorities – married an East German woman. The marriage ceremony, which took place in Turkey, went smoothly, until the man reentered West German borders with his East German wife. Suspecting him of being an East German spy, the West German police came knocking on his door, searched through his bag, and interrogated him. Fearing imprisonment, the man spent a year hiding at a friend’s house in Duisburg and was planning to relocate to a new hideout in Frankfurt. Whether or not the man was one of the Stasi’s up to 189,000 “unofficial collaborators” (inoffizielle Mitarbeiter) is unknown, for the archival trail ends there. The staffer responsible for opening the prime minister’s mail apparently rerouted it to the headquarters of the Workers’ Welfare Organization in Cologne, where it sat in a box for decades before being donated to Germany’s migration museum.Footnote 102

Though usually directed at men, Turkish anxieties about adultery were also staged on women’s bodies.Footnote 103 One female guest worker from Kastamonu was warned that she might “forget” her husband. “You’ll have a man on every finger of your hand,” her husband’s uncle told her, and “you’ll divorce your husband.” She later interpreted these concerns as rooted in her fellow villagers’ “stupid” fear that women would cheat on their husbands if they worked outside the home. “I went [to Germany] nonetheless and proved them wrong,” she boasted.Footnote 104 Concerns also abounded about the infidelity of guest workers’ wives who remained in Turkey. One male villager warned that “rather than having sex in Germany,” a guest worker must “respect his wife and think about her pleasure,” otherwise “the time will come when she sleeps with another man.”Footnote 105 Such cases, while generally less common, did exist. In 1966, Cumhuriyet reported that the mother of a guest worker had stalked her daughter-in-law and caught her “red-handed” cohabitating with another man. After being found guilty of adultery – a crime under Turkish law until 1996 – the young woman violently attacked her mother-in-law outside of Istanbul’s Criminal Court.Footnote 106

Suspicious of their wives’ infidelity, male guest workers often placed them under the watchful eye of relatives. This practice was far more common in Turkish villages, where migration’s destabilizing effect on family structures was especially pronounced. In the village of Boğazlıyan, 56 percent of wives left behind lived alone with their children, whereas 29 percent lived with members of their husbands’ families.Footnote 107 The mother-in-law of one twenty-one-year-old woman slept by her side every night during her husband’s absence and, in another case, a fourteen-year-old brother-in-law kept watch.Footnote 108 While guest workers justified this supervision as crucial to “protecting” their wives against the dangers of living alone and the unwanted advances of other men, many women felt that their freedom was being constrained. Fatma, whose father departed for Germany in 1972, explained that her mother was forced to spend a year living with her “very hierarchal” in-laws, where she feared contradicting their authority and was “not allowed” to eat at their table. Estranged from her own parents due to their disapproval of her “poorer” husband, Fatma’s mother’s only solace was the comfort of female friends, several of whom were in similar situations.Footnote 109

However unfounded, the hot topic of guest workers’ adultery circulated throughout Turkish popular culture during the 1970s – from folkloric village songs to novels and films produced in cities. In one popular song, “Almanya Dönüşü” (Return from Germany), a wife is furious when her husband appears at her doorstep after having cheated on her with a blonde German “slut.”Footnote 110 To make matters worse, he had broken his promise to send her money: “Where are those bundles of money you used to dream about? Where is that multi-storied home? Where are those cars?” Likewise, in the iconic Black Sea region folksong “Almanya Acı Vatan” (Germany, Bitter Homeland), a wife condemns her husband for remarrying in Germany, failing to return after five years, and not sending a single letter. “What good is this money?” the singer asks. “Your family with five children, all of them miss you … You have made your home worse. Worse thanks to you.”Footnote 111 This ballad became so ingrained in Turkish culture that director Şerif Gören chose Almanya Acı Vatan as the title of his 1979 feature film, whose poster depicts a mustachioed guest worker surrounded by two beautiful blonde women drinking beer.Footnote 112

These themes appear in other Turkish films of the time.Footnote 113 In Türkân Şoray’s 1972 film Dönüş (The Return), a woman named Gülcan learns to read and write for the sole purpose of sending her husband letters, but he never responds, and a prominent elderly villager sexually assaults her. When her husband finally returns, he brings a German wife and baby, whom Gülcan must care for after he dies in an accident.Footnote 114 Released just two years later, Orhan Elmas’s 1974 film El Kapısı (Foreign Door) centers on a female guest worker named Elvan who takes off her headscarf, wears sleeveless dresses, sings in a nightclub, and engages in sex work. After rumors circulate in her home village, her husband travels to Munich and fatally stabs her to protect his honor. The portrayal of both Gülcan and Elvan as victims of their husbands further reflects the importance of Turkey’s rural–urban divide: produced in cities, the films’ critique of gender relations in the countryside substantially overlaps with West Germans’ stereotypes about Turkish “village culture” that were instrumentalized to foster racism and tropes of cultural incompatibility.

The widespread reach of these tragic songs and films likely influenced Gülten Dayıoğlu’s 1975 book of short stories Geride Kalanlar (Those Who Stayed Behind). The cover art, which depicts five somber village women, sets the tone visually. In the book’s opening vignette, a thirty-year-old woman travels to a city to visit a doctor but has difficulties articulating why she feels unwell. When the doctor asks whether she is married, she responds with an ambiguous “Eh.” She has a husband, she says, but she has not seen him for seven years. Although she is comforted by the knowledge that German women have little fondness for “men with black hair, black eyes, and black mustaches,” she has heard rumors that her husband has remarried and conceived a son with a woman with “blonde hair” and “sky-blue eyes.” At first denying the accusation, the husband spreads rumors that she is “crazy,” making her question her own sanity.Footnote 115

Although some adulterous husbands returned to Turkey after steamy affairs abroad, the subject largely remained an unknown, or a deliberately repressed, taboo within families. Even fifty years after the incident, Yaşar hesitated to answer questions about his adultery, while his neighbors eagerly gossiped about the scandal.Footnote 116 Nowhere are the enduring emotional scars clearer, however, than in Marcus Attila Vetter’s 2006 autobiographical documentary film Mein Vater, der Türke (My Father, the Turk), which traces Vetter’s journey from Germany to a small Anatolian village to meet his biological father, who had abandoned his German mother upon hearing of the pregnancy.Footnote 117 When Vetter meets his long-lost family, including his half-siblings and his father’s Turkish wife, a tearful reunion ensues. The documentary won Europe-wide acclaim and the award for best long-form documentary at the 2007 San Francisco International Film Festival. The festival’s website puts it best: Vetter’s story, representative of so many other guest worker families, shows “how one man’s actions changed the course of an entire family” and unearths “more than thirty years of pent-up feelings and questions.”Footnote 118

Children as Victims and Threats

The other core component of the breakup and abandonment of the family was the situation of guest worker children (Gastarbeiterkinder), whom Turks and Germans alike viewed as both victims and threats. The perception of guest worker children as a threat was particularly pronounced in Germany, fueling racist tropes that emphasized Turks’ inability to “integrate” into German society. The opposite threat, however, prevailed in Turkey: excessive integration. Turks in the homeland denigrated guest worker children, even more so than their parents, for having undergone a process of Germanization whereby they adopted German mannerisms and fashions, had premarital sex, lost their Muslim faith, and – most egregiously – spoke German better than Turkish. The very possibility that Turks, and particularly Turkish children, could become culturally German was vital: not only did it contradict German discourses about migrants’ failed integration, but it also exposed the fluidity of Germany’s rigid blood-based identity.

The experiences of guest workers’ children varied greatly and changed over time – so much so that it is impossible to speak about a singular “second generation.” Especially amid the family migration of the 1970s, many children were born or raised primarily in Germany (Figure 1.6). Yet the overwhelming emphasis on children on German soil obscures the reality that many children remained in Turkey and never set foot in Germany, while up to 700,000 others – colloquially called “suitcase children” (Kofferkinder) – regularly traveled back and forth. Reflecting the broader destabilization of family life, children left behind in Turkey lived with a single parent (usually their mothers) or, in cases when both parents worked abroad, with grandparents and other relatives. The perception that these children were victims or “orphans” who suffered because of their parents’ abandonment or repeated uprooting fed into exclusionary tropes in both countries that blamed guest workers for the breakup of family life. Yet victimization tropes did not reflect the reality of all children left behind, as many found advantages, and even power, in their situations.Footnote 119

Figure 1.6 Turkish children outside a West German elementary school in Duisburg-Hamborn.

In Turkey, children left behind were often victimized as “orphans” who were emotionally distressed and poorly raised. This depiction was especially true in cases of absent fathers in villages, who typically, due to gendered social conventions, were the primary breadwinners, had been granted more extensive education than their wives, and handled disciplinary matters within the family. One teacher in a Turkish village worried about the fifty “half-orphans” in his classroom being raised by mothers and grandmothers who could “not even write their own names.” These children, many of whom apparently also lacked discipline and diligence, “pay for the economic survival of their families with their own futures.”Footnote 120 While this denigration of female caretakers reinforced gendered tropes about male supremacy in the household, it also reflected many mothers’ real struggles during their husbands’ absences. In Nermin Abadan-Unat’s 1976 study of 373 wives left behind in the province of Boğazlıyan, nearly half reported that they assumed greater responsibility for tasks otherwise completed by men, such as shopping for major purchases, borrowing money, and collecting debts, and one quarter expressed difficulties “establishing authority and discipline.”Footnote 121

For many children left behind, being separated from their parents was a painful experience. When she was just in the fifth grade, Alev Demir wrote a series of poems capturing this sense of estrangement. In a poem called “Yearning,” she lamented: “I am distant from my mother and father. I do not know what to do because I am alone. I cannot laugh. I cannot cry. I do not like yearning.”Footnote 122 Similarly powerful is Murat Çobanoğlu’s popular 1970s folksong “Oğulun Babaya Mektubu” (A Son’s Letter to His Father), in which a teenage son condemns his “cruel” father for breaking his promise to “return quickly” and having become “attached” to Germany. Eleven years have passed, and the family’s situation has become “terrible”: their house is “in ruins,” they cannot afford to eat warm food, and their neighbors have “stigmatized” and “turned against” them. Although the son has assumed his father’s caretaker role, he will soon leave for military service and will be unable to provide for the family. In a subsequent song, the father admits to crying upon reading the letter and, again, promises that he will return – but he never does.Footnote 123

Some children, however, recalled the shift in family relations fondly. Yusuf K. from the village of Buldan described the absence of “fatherly authority” as a “nice time.” His mother was not as “strict or authoritarian,” and she let him play outside for hours without a curfew. Whereas he found it difficult to bond emotionally with his father, “I could tell my mother all my desires without being embarrassed.”Footnote 124 In cases of the extended absence of mothers and fathers, some children felt even more comfortable with their surrogate parents. “I considered my grandmother my actual mother,” Ebru T. explained, noting that, despite her parents visiting her village of Eskişehir only once per year, she did not miss them. When her parents finally brought her to Germany at age eight, she found it difficult to relate to them. To her, they were “foreign people” who barely existed.Footnote 125 Reiterating the notion of parents becoming “foreign,” another child happily recalled that her grandparents “treated me like a queen” and “gave me everything I wanted,” and that she was “ambivalent” about her parents.Footnote 126 Saddened by this estrangement, some parents regretted their decisions to leave their children behind, with one admitting that she was not a “good mother.”Footnote 127

But not all children left behind stayed in Turkey permanently. Especially central to transnational tropes of victimization were the “suitcase children,” a term that evoked their never-ending transience, requiring them to keep their suitcases both literally and metaphorically packed. In the decades since, the situation of the suitcase children has been called one of Turkish-German migration history’s “most difficult and painful” taboos, riddled with “unspoken trauma” in which parents violated their children’s basic trust and fostered lifelong misconceptions that they were worthless and unlovable. The prominent Turkish-German politician Cem Özdemir, who grew up in Germany, even recalled years later that he had suffered a recurring childhood “nightmare” that he, too, would be abandoned by his parents and sent back to Turkey.Footnote 128

Despite the subsequent repression of suitcase children’s psychological trauma, the phenomenon was no secret at the time. Rather, the plight of suitcase children was a regular theme in both Turkish and German discourses about migrants. An animated short film produced in 1983 as part of a pedagogical West German cassette series aimed toward Turkish guest worker families depicts a young boy named Ali who travels to Munich to reunite with his parents after living with his grandparents in the village of Gülbahar.Footnote 129 Symbolic of Ali’s physical and psychological burden, he stands with a suitcase grasped tightly in his hand, an enormous bindle slung behind his shoulder, and another bag jammed in the crook of his elbow. After jumping into his mother’s arms upon his arrival, his enthusiasm for Germany soon deteriorates. Homesick for his village, he misses his best friends (who, in a commentary on guest workers’ rural origins, are a rooster and a donkey) and spends his free time watching Turkish movies. Within a month, the situation turns brighter as he begins to integrate into German society, learn German, make friends, and dream of becoming an engineer. Yet the happy tale sours again when his father sends him back to Turkey. In the ominous closing scene, Ali – sitting at a desk with a notepad, protractor, and abacus – realizes that “there are, of course, no engineering schools in the village.” The film enjoyed a positive reception in Germany, as its didactic message helped Turkish and German children develop intercultural sympathy based on their shared struggles with making new friends.Footnote 130 The film also offered room for other interpretations by emphasizing the victimization of Turkish children at the hands of their parents, and by implying the superiority of life in West Germany’s urban and “modern” milieu.

A similar narrative, though with a different conclusion, appears in Turkish author Gülten Dayıoğlu’s 1980 novel Yurdumu Özledim (I Miss My Homeland). When a young boy named Atil learns that his parents will take him to Munich, his teacher hands him a Turkish flag and photograph of Atatürk and pontificates about Atil’s need to retain his national pride: “You are the child of an exalted and noble country with a glorious past that has lasted many thousands of years. You must be proud that you are a Turk and you may not feel inferior. Beware of disgracing your land and your people … Never forget that you are a Turk!”Footnote 131 Influenced by his teacher’s advice, Atil approaches life in Germany critically. Feeling like “a bird in a cage,” he rants that he would “rather eat dry bread and walk around in dirty clothes at home” than stay in Germany any longer. To Atil’s delight, his outburst helps his parents recognize their own homesickness, and the family returns to Turkey, with the novel ending happily.

Although the fictional stories of Ali and Atil portray their rural origins as central to their culture shock, many suitcase children came from cities and had a higher socioeconomic status. Born in Ankara in 1972, Bengü spent the first year of her life in Munich with her parents, both guest workers, who despite having white-collar jobs in Turkey opted to work in German factories for higher wages. Because they worked long hours, they placed Bengü under the daily care of a “German grandma” (Deutsche Oma) – an experience shared by many other guest worker children – until they discovered her husband’s borderline alcoholism.Footnote 132 Absent suitable childcare, they sent one-year-old Bengü back to Ankara to live with her grandparents. Over the next years, they sent her back and forth – at age two to Germany, at age five to Turkey, where she stayed until completing high school. During this time, her parents sent her regular letters and postcards and, like many other guest workers, recorded their voice messages on cassette tapes. Bengü’s younger sister, who lived with their parents in Germany, sent her colorful drawings. In one drawing, which aptly reflects the emotional experience of family separation, a house stands between Bengü on one side and her parents and sister on the other. After twelve years apart, Bengü ultimately chose to reunite with her parents and sister and studied English at a German university.

Murad, another suitcase child, experienced a similar situation. Born in 1973 in the West German city of Witten, he was sent to Istanbul to stay with his grandparents due to insufficient childcare. After just six months, his parents missed him so much that they brought him back to Germany. Eight years later, they sent him back to Istanbul so that he could become accustomed to Turkish schools in anticipation of the family’s planned remigration. Like so many other guest workers, however, they just “played with the idea of going back” and “never fully committed.”Footnote 133 Waiting for a return migration that never materialized, Murad thus spent his teenage years separated from his parents and younger sister until, like Bengü, he returned to Germany for university. Decades later, at age forty, Murad expressed pride in his identity as a suitcase child and emphatically rejected the notion that he was a “victim.” Instead, his experiences made him a “special kid” and “improved [his] personality” by exposing him to multiple perspectives. Murad did, however, experience long-term conflicts within his family. His relationship with his younger sister remained strained and distant throughout his life, as they did not grow up together and had vastly different childhoods. And his mother, the true “victim,” in his words, remained racked with guilt her entire life, missing the lost years she could have spent with her son.

As the transience of the suitcase children reveals, the categories of “children left behind” and “children born or raised in Germany” were not mutually exclusive. Common to their experiences, however, was the feeling that they were caught between two cultures, questioning their own identities. These concerns, though ubiquitous in sources on Turkish-German migration history, are particularly well expressed in a 1980 volume of Turkish children’s poems and short stories titled Täglich eine Reise von der Türkei nach Deutschland (Everyday a Journey from Turkey to Germany), whose German editors sought to give voice to youths “without a homeland.” One boy described the title’s meaning as a public–private spatial dichotomy: “When I leave my parents’ house in the morning, I leave Turkey. I then go to my job or to my friends and am in Germany. In the evenings, I return to my parents’ house and am back in Turkey.” More common than the spatial dichotomy, however, was the opposition of cultural and national identities. In one poem, a boy named Mehmet wrote, “I stand between two cultures / the Turkish and the German / I swing back and forth / and thus live in two worlds.”Footnote 134 This constant “swinging” fostered internal confusion. As another boy, Türkan, questioned: “Some say: ‘You are a German.’ Others say: ‘You are a German Turk.’ … My Turkish friends call me a German! … But what am I really?”Footnote 135 Reprinted verbatim in the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, the children’s writings conjured broader German sympathy for their plight.Footnote 136

Yet, overwhelmingly, Germans viewed Turkish children less as victims of confused identities and more as threats. They condemned their “illiteracy in two languages” as a burden on the education system that not only diminished the quality of German students’ education but also, according to more explicitly racializing rhetoric, portended Germany’s genetic and intellectual decline.Footnote 137 These concerns coincided with Germans’ reckoning with the broader transformation of urban space with the rise of family migration. As migrant families moved out of factory dormitories and into apartments, Germans fled to “nicer” parts of the city and decried the emergence of “Turkish ghettos” (like the iconic “Little Istanbul” in West Berlin’s Kreuzberg district) that seemingly testified to Turks’ unwillingness to integrate.Footnote 138 These “parallel societies,” as Germans often called them, were envisioned as particular sites of criminality and unrest, in which rowdy Turkish teenagers skipped class, loitered at parks, sold drugs, sexually assaulted German girls, and shouted insults like “German pig!” at elderly women.Footnote 139

Fears of Turkish children were exacerbated by migrants’ higher birthrates, with Turkish women derided as having their “wombs always full.”Footnote 140 German birthrates, by contrast, had declined due to the release of the birth control pill in 1961, the legalization of abortion in 1973, and the growing number of women working outside the home. This imbalance stoked existential fears, widely reported in the media and repeatedly discussed among policymakers, that Turks would numerically overtake Germans within a matter of decades.Footnote 141 Especially infuriating was guest workers’ alleged abuse of the social welfare system’s child allowance (Kindergeld), whereby residents received a monthly lump sum per child even if the child did not live in Germany. One newspaper reported on the case of a Turkish guest worker in Heidelberg who apparently had twenty-three children between his two wives in Turkey and earned an impressive 1,440 Deutschmarks in child allowances monthly, which far exceeded the amount of his salary.Footnote 142 As criticism of “welfare migrants” mounted, West Germany reformed its Kindergeld policy in 1974, offering less money for children who lived outside the European Economic Community.Footnote 143