Introduction

South-east Asian biodiversity has declined dramatically as a result of habitat loss and degradation and overhunting (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Batters, Belant, Bennett, Brunner and Burton2012; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Sreekar, Brodie, Brook, Luskin and O'kelly2016). Within South-east Asia, deciduous dipterocarp forests are of particular concern as they are the most threatened of all tropical forest types (Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Lipkin, Sullivan, Benowitz, Pau and Keppel2012; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova and Tyukavina2013). Currently, only about 156,000 km2 of deciduous dipterocarp forest remain in mainland South-east Asia (Wohlfart et al., Reference Wohlfart, Wegmann and Leimgruber2014). However, these forests are crucial for a wide range of globally threatened species (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Chundawat, Nichols and Kumar2004a; Steinmetz, Reference Steinmetz2004; McShea et al., Reference McShea, Koy, Clements, Johnson, Vongkhamheng and Aung2005, Reference McShea, Davies and Bhumpakphan2011; Gray, Reference Gray2012).

Deciduous dipterocarp forests are also highly seasonal habitats, experiencing 5–6 months of drought per year (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Newton, DeFries, Ravilious, May and Blyth2006). In such dry tropical habitats, water and food resource availability may be limiting factors for the distributions, movements and home ranges of many species during the dry season (Aung et al., Reference Aung, McShea, Htung, Than, Soe, Monfort and Wemmer2001; Redfern et al., Reference Redfern, Grant, Biggs and Getz2003), and waterholes are likely to be a substantial component of water surface availability, providing important water resources and foraging habitat for many species (Keo, Reference Keo2008; Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Attum, Robinson and Sandoka2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Buckingham and Dolman2010; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012). Utilization of waterholes by wildlife is also likely to be higher during the dry season (Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Attum, Robinson and Sandoka2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012). Levels of crucial water availability in South-east Asian deciduous dipterocarp forests are likely to be further impacted by predicted decreases in precipitation and increases in temperature associated with global climate change (Dai, Reference Dai2013; Trenberth et al., Reference Trenberth, Dai, Van Der Schrier, Jones, Barichivich, Briffa and Sheffield2014).

The deciduous dipterocarp forests of eastern Cambodia may be particularly vulnerable (Yusuf & Herminia, Reference Yusuf and Francisco2010; Climate Investment Funds, 2014). The Eastern Plains Landscape, a protected area complex covering c. 14,000 km2 in eastern Cambodia and southern Viet Nam, supports one of the largest extents of deciduous dipterocarp forests remaining in South-east Asia. This landscape is home to several globally threatened species of mammals and birds (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Ou, Huy, Pin and Maxwell2012a; O'Kelly et al., Reference O'Kelly, Evans, Stokes, Clements, Dara and Gately2012; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Ko, Norin and Phearun2013b) including the Asian elephant Elephas maximus, banteng Bos javanicus, Eld's deer Rucervus eldii, leopard Panthera pardus, and globally threatened waterbirds such as the giant ibis Thaumatibis gigantea, white-shouldered ibis Pseudibis davisoni and green peafowl Pavo muticus. During the dry season water availability is mainly limited to perennial rivers and waterholes, which are an essential part of the forest and are used by several of these threatened large species (Keo, Reference Keo2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012; Gray et al., Reference Gray, McShea, Koehncke, Sovanna and Wright2015b). However, little is known about the relationship between wildlife and waterholes in South-east Asian deciduous dipterocarp forests with the exception of two studies on the giant and white-shouldered ibises (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Buckingham and Dolman2010, Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012). Although these studies suggested waterholes are important for these two species, it is largely unknown how they impact the other threatened species in this landscape and, for example, how the morphological characteristics of the waterholes affect usage.

We focused on waterhole usage by six dry forest specialists of high conservation concern that utilize waterholes for foraging and/or drinking, including four birds, the giant ibis (categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List; Birdlife International, 2017), green peafowl (Endangered), lesser adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus (Vulnerable) and Asian woolly-necked stork Ciconia episcopus (Vulnerable), and two large herbivorous mammals, banteng (Endangered) and Eld's deer (Endangered) (McShea et al., Reference McShea, Koy, Clements, Johnson, Vongkhamheng and Aung2005; Keo, Reference Keo2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012; Gray et al., Reference Gray, McShea, Koehncke, Sovanna and Wright2015b). We hypothesized that (1) water availability in a given waterhole and (2) waterhole characteristics (e.g. size, surrounding vegetation, and availability of adjacent waterholes) will be associated with different levels of use by these target species (especially the giant ibis, lesser adjutant and Asian woolly-necked stork, which feed in the waterholes), and (3) increased human activity at or near waterholes will probably reduce use.

Study area

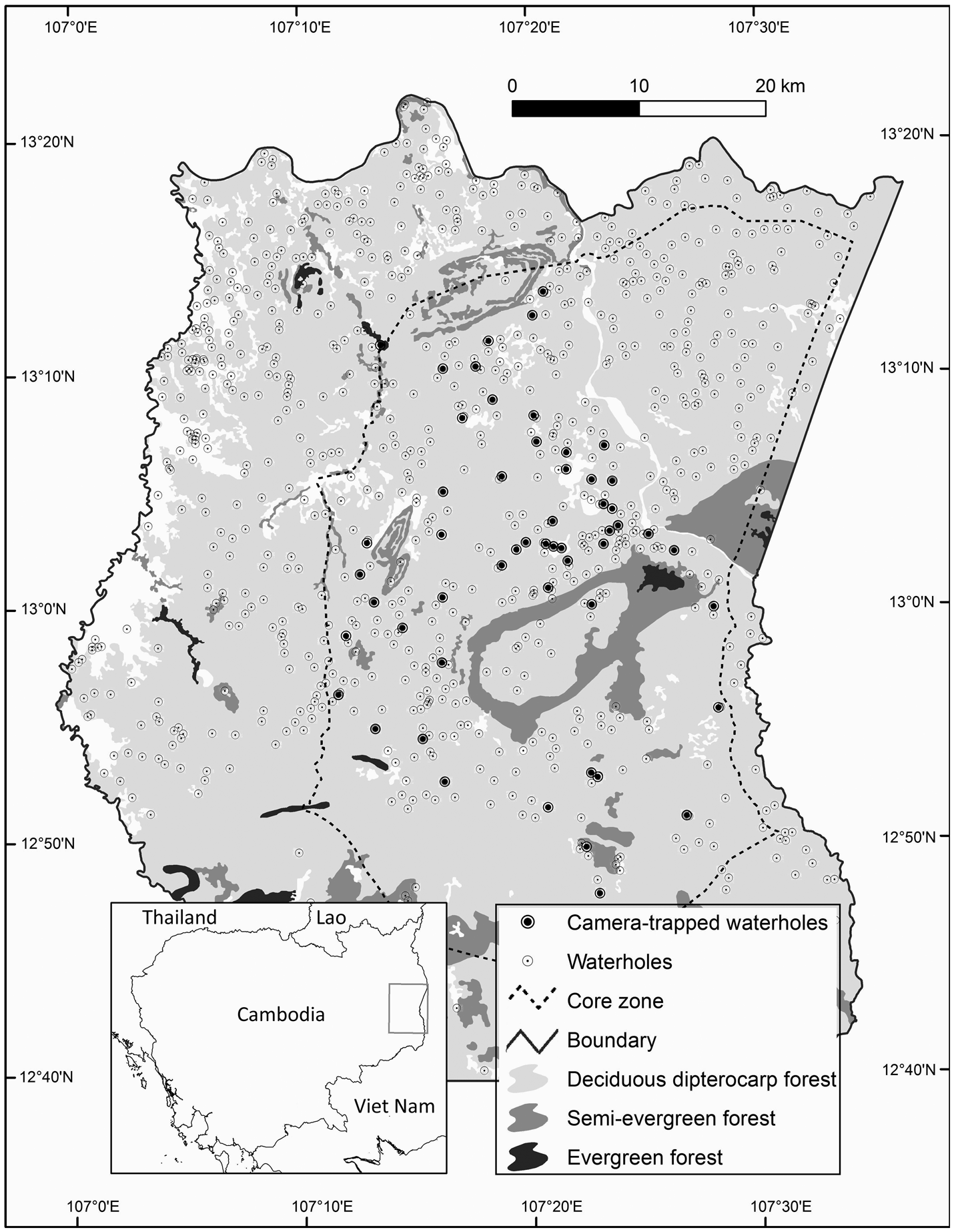

The study was conducted in the core zone of the 3,729 km2 Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary, formerly known as the Mondulkiri Protected Forest (Fig. 1). The core zone of the sanctuary (1,292 km2), previously designated as a Special Ecosystem Zone under a draft Forestry Administration management plan, is also recognized as a possible site for tiger reintroduction (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Crouthers, Ramesh, Vattakaven, Borah and Pasha2017). This is the least disturbed area of the Sanctuary and supports the highest densities of large ungulates in Cambodia (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Phan, Pin and Prum2012b). Vegetation of the Sanctuary is predominantly deciduous dipterocarp forests dominated by Dipterocarpaceae, including Shorea siamensis, Shorea obtusa, Dipterocarpus tuberculatus, Dipterocarpus obtusifolius and Dipterocarpus intricatus (McShea et al., Reference McShea, Davies and Bhumpakphan2011; Pin et al., Reference Pin, Phan, Prum and Gray2013). Srepok also supports the largest population of banteng in Cambodia (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Prum, Pin and Phan2012c) and is a priority site for leopard Panthera pardus in Indochina (Gray & Prum, Reference Gray, Phan, Pin, Gray and Prum2012; Rostro-García et al., Reference Rostro-García, Kamler, Ash, Clements, Gibson and Lynam2016). The area is influenced by two distinctive seasons, wet (May–October) and dry (November–April), with a mean total annual rainfall of 1,500–1,800 mm (Bruce, Reference Bruce, Sunderland, Sayer and Hoang2013). During the dry season the area experiences frequent forest fires that create an open understory and reduce canopy cover (McShea et al., Reference McShea, Davies and Bhumpakphan2011; Ratnam et al., Reference Ratnam, Tomlinson, Rasquinha and Sankaran2016).

Fig. 1 Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary, Cambodia, showing waterholes and the 54 waterholes that were camera-trapped during the dry season of December 2015–June 2016.

Methods

Waterhole selection and camera-trapping

The coordinates of waterholes used in this study were provided by the Eastern Plains Landscape Project, GIS & Remote Sensing Department, WWF-Cambodia (WWF-Cambodia, 2015, unpubl. data). Fifty-four waterholes were randomly selected from an estimated 350 waterholes in the core zone of the sanctuary using Hawth's Analysis Tools (Beyer, Reference Beyer2004) for ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, Redlands, USA). Camera traps (infrared, remote-trip digital camera units Reconyx PC900 HyperFire Professional IR, RECONYX, Holmen, USA) were placed at waterholes during the dry season of December 2015–June 2016 (Fig. 1). Camera traps (one per waterhole) recorded date and time automatically on all photographs, were not baited, and were set to operate 24 h per day with a 1-minute delay between photographs. To maximize encounters of species, camera traps were placed 2–15 m from the water's edge in an area with the highest diversity of wildlife footprints (camera traps were moved to follow the recession of the water level as the dry season progressed). Depending upon topography and location, camera traps were either placed on trees or poles at a suitable location at a height of 50–100 cm, to increase the chance of encountering large ungulates. Maximum trigger distance was checked to make sure cameras could detect animals from a distance of c. 20 m, and all cameras were set to medium sensitivity to minimize false captures associated with moving vegetation.

Data collection

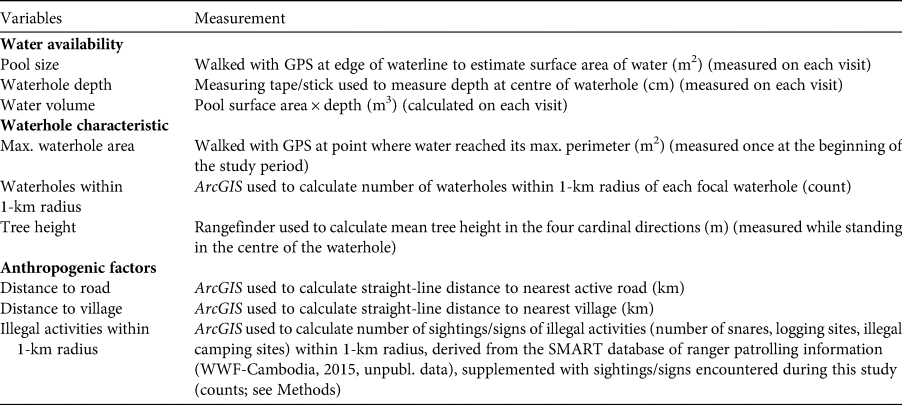

Camera-trapped waterholes were visited every 2 weeks, in a total of 9 visits for the study period. We collected three parameters related to water availability (water depth, pool size, and water volume), three related to physical characteristics of the waterhole and the surrounding landscape (maximum waterhole area, number of waterholes within a 1-km radius, and height of nearest trees adjacent to the target waterhole) and three parameters related to potential human impacts (distance to nearest village, distance to nearest active road/trail, and number of illegal activities within a 1-km radius); see Table 1 for a description of how these parameters were measured and how often.

Table 1 Variables, and method of measurement, used to describe 54 waterholes in the Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary (Fig. 1) during the dry season of December 2015–June 2016.

Data analysis

Consecutive photographs of the same species taken at an interval of at least 30 minutes, or non-consecutive photographs of the same species at the same station, were defined as notionally independent photographs (O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, Kinnaird and Wibisono2003). Camera-trap photo management and the creation of the database of encountered species was conducted using camtrap R (Niedballa et al., Reference Niedballa, Sollmann, Courtiol and Wilting2016) in R 3.3 (R Core Team, 2016).

We used these photos as an index of the frequency of waterhole use by the target species (but not as an indicator of movement or behaviour at waterholes). Counts of these notionally independent photographs (i.e. one photograph equalling one count regardless of the number of individuals photographed) of focal species were modelled as response variables, with water availability, waterhole characteristics and human disturbance variables as predictor variables. All continuous variables were centred and scaled using scale in R. We used trap-nights of each camera trap as an offset in fitting the models (Kotze et al., Reference Kotze, O'Hara and Lehvävirta2012).

R package glmmADMB (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Skaug, Ancheta, Ianelli, Magnusson and Maunder2012) was used to fit Poisson or negative binomial models in a generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) framework for banteng, Eld's deer, giant ibis, lesser adjutant and Asian woolly-necked stork. Because of the large number of zero counts in the green peafowl dataset, we used pscl (Achim et al., Reference Achim, Christian and Simon2008) to fit zero-inflated regression models, allowing us to model the excess zeros and the count values independently (Zuur & Ieno, Reference Zuur and Ieno2016).

Prior to analysis we checked the data for outliers, overdispersion and correlations among predictor variables (Zuur et al., Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009; Zuur & Ieno, Reference Zuur and Ieno2016). Variables with correlations > 0.5 were not included in the same model. There were no strong correlations among predictor variables except between water volume and pool size (r = 0.93). We fitted predictor variables into models to determine the effect of each on the species count data; we also tested additive models of a combination of selected predictor variables. In addition, we tested models that included both waterhole characteristics and human disturbance variables.

Model selection was based on AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and AIC weights (Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2003). However, when there was uncertainty based on these criteria, we employed model averaging to compute average estimates of beta coefficients of candidate models. We conducted model averaging of the most supported candidate models where ΔAIC ≤ 2.00. We used MuMIn (Barton, Reference Barton2018) for model averaging.

Results

A total of 49 waterholes of the 54 camera-trapped dried out by April 2016. However, eight refilled with water following rains during the first week of May 2016. Camera traps operated on average 138 trap-nights per waterhole (range 44–182 trap-nights). A total of 6,444 trap-nights captured > 4,700 notionally independent photographs of at least 29 species (Supplementary Table 1). Among the target species, lesser adjutant and banteng were the most frequently encountered (Supplementary Table 1). Camera traps captured the six target species utilizing waterholes in several ways, but there appeared to be general patterns of use. Banteng and Eld's deer were recorded drinking and grazing at waterholes, lesser adjutant and Asian woolly-necked stork foraged in the deeper areas of the pools, and giant ibis and green peafowl foraged in dry and/or saturated substrates at the edges of the waterholes (Plate 1).

Plate 1 Photographs of (a) banteng Bos javanicus, (b) Eld's deer Rucervus eldii, (c) giant ibis Thaumatibis gigantea, (d) green peafowl Pavo muticus, (e) lesser adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus and (f) Asian woolly-necked stork Ciconia episcopus drinking and/or foraging at waterholes during the dry season of December 2015–June 2016.

Models (both GLMMs and zero-inflated regression models) that had AIC weights ≥ 0.01, as well as all null models, describing the relationship between counts of notionally independent photos of target species utilizing waterholes and predictor variables are shown in Table 2 (all models are shown in Supplementary Table 2). The most supported model had an AIC weight > 0.85 for Eld's deer and green peafowl, two top candidate models (ΔAIC ≤ 2.00 and w i > 0.85) were selected for banteng and Asian woolly-necked stork, three top candidate models (ΔAIC ≤ 2.00 and w i = 0.81) were selected for lesser adjutant. Four top candidate models (ΔAIC ≤ 2.00 and w i = 0.91) were selected for giant ibis (Table 2).

Table 2 Summary of all GLMMs and zero-inflated regression models that had AIC weights ≥ 0.01, used to explain the number of notionally independent photographs of six target species at 54 waterholes. For definitions of predictor variables see Table 1.

1Number of parameters.

2Akaike Information Criterion.

3AIC weights.

4 GLMMs.

5 Zero-inflated regression models.

*Quadratic polynomial of water depth.

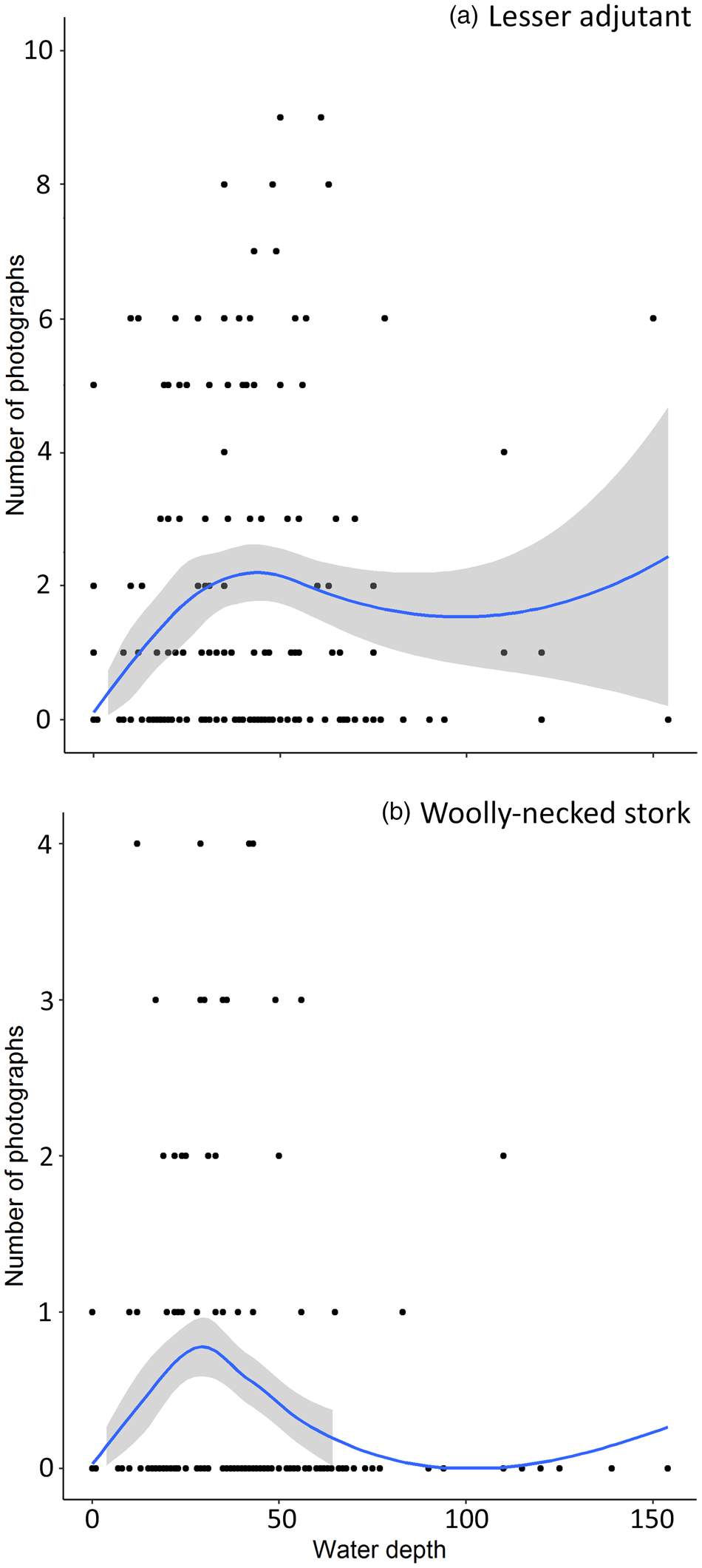

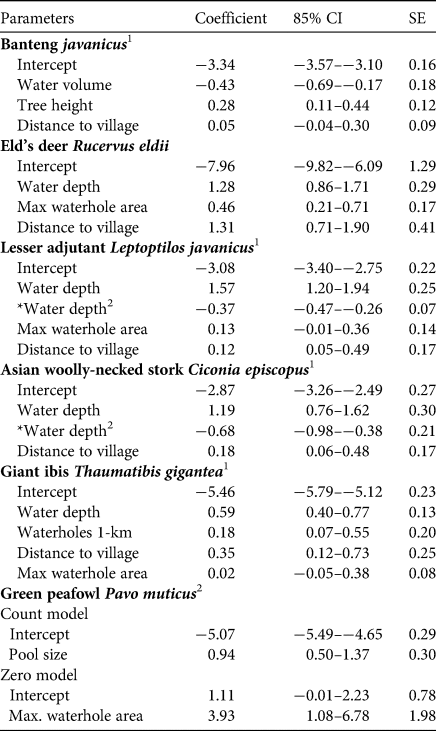

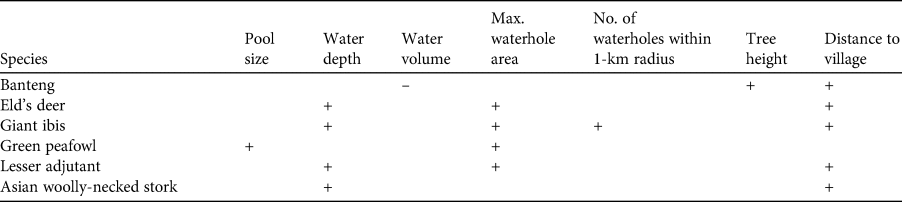

Estimated beta coefficients from the top models and model averaging across the most supported candidate models for banteng, Eld's deer, lesser adjutant, Asian woolly-necked stork, giant ibis and green peafowl are shown in Table 3. The direction of the impacts of waterhole characteristics on the utilization by the target species are shown in Table 4. Overall, deeper and/or larger waterholes were preferred by all species except banteng. However, lesser adjutant and Asian woolly-necked stork had a curvilinear relationship with water depth, reflecting a preference up to a threshold depth of 30–40 cm and then declining usage at greater depth (Fig. 2). Banteng showed a negative relationship with water volume and preferred waterholes surrounded by tall trees. The Critically Endangered giant ibis was the only species that was also associated with the abundance of neighbouring waterholes. All species except green peafowl were more likely to occur at waterholes further from villages.

Fig. 2 Curvilinear relationship of notionally independent photographs of (a) lesser adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus and (b) Asian woolly-necked stork Ciconia episcopus with waterhole depth (measured at the centre of each waterhole). The curve was fitted using loess smoothing.

Table 3 Estimated coefficients, 85% CI and SE for regression models predicting the number of notionally independent photos of six target species at 54 waterholes. For definitions of variables see Supplementary Table 1.

1 GLMM averaging.

2 Zero-inflated function models.

*Quadratic polynomial of water depth.

Table 4 Summary of the relationships (positive, negative, or no effect) between measured predictor variables and the number of notionally independent photos of six target species at waterholes. Distance to roads and number of illegal activities detected around waterholes did not show an effect.

Discussion

We provide the first detailed study of the variables influencing utilization of waterholes by wildlife in a dry dipterocarp forest. As predicted, our results suggested that water availability (water depth and pool size) played a major role in the utilization of waterholes by six globally threatened target species. In addition, waterhole characteristics and associated landscape characteristics including maximum waterhole area, proximity to other waterholes in the surrounding landscape, height of trees adjacent to waterholes, and human disturbance, particularly distance to the nearest village, also influenced waterhole use by these species (Table 4).

Importance of waterholes for large herbivores

Deeper waterholes retained water for longer than shallower ones, and the deeper waterholes probably provide critical drinking water for ungulates. Most large herbivores need to access drinking water to complement forage consumption during the dry season when food and water are scarce (Western, Reference Western1975; Manser & Brotherton, Reference Manser and Brotherton1995; Gedir et al., Reference Gedir, Cain, Krausman, Allen, Duff and Morgart2016). In addition, some will forage as well as drink at waterholes (Valeix et al., Reference Valeix, Fritz, Matsika, Matsvimbo and Madzikanda2008), and our photographs appear to support this (Plate 1). Thus, the availability of water probably influences movement and home ranges during the dry season, although our data was unable to address movement of individual animals (Aung et al., Reference Aung, McShea, Htung, Than, Soe, Monfort and Wemmer2001; Redfern et al., Reference Redfern, Grant, Biggs and Getz2003; Smit et al., Reference Smit, Grant and Devereux2007). Our results show a positive relationship between maximum waterhole area and depth for Eld's deer, but a negative relationship between water volume and use of waterholes by banteng. The reason for the latter is unclear but banteng were recorded at 78% (42) of the 54 waterholes, suggesting they were widely distributed in the study area compared to Eld's deer, which were recorded at only six waterholes. Tree height adjacent to waterholes also had a positive effect on utilization of waterholes by banteng. Tall deciduous dipterocarp trees may provide understory vegetation that is particularly suitable for wild cattle during the dry season (Steinmetz, Reference Steinmetz2004; Gray, Reference Gray2012). Although large herbivores play an essential role as the primary prey for large carnivores (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Kumar, Link and Hines2004b; Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Henschel, O'brien, Hofmeyr, Balme and Kerley2006, Reference Hayward, Jędrzejewski and Jedrzejewska2012, Reference Hayward, Lyngdoh and Habib2014; Wolf & Ripple, Reference Wolf and Ripple2016), little is known about the role these herbivores have in maintaining and structuring these Asian savannah ecosystems (Ratnam et al., Reference Ratnam, Tomlinson, Rasquinha and Sankaran2016). Nevertheless, the role of waterholes in sustaining large herbivores is likely to be vital in the deciduous dipterocarp forests of the region. Natural salt licks are also a key resource for large mammals (Matsubayashi et al., Reference Matsubayashi, Lagan, Majalap, Tangah, Sukor and Kitayama2007; Lameed & Jenyo-Oni, Reference Lameed, Jenyo-Oni and Lameed2012; Matsuda et al., Reference Matsuda, Ancrenaz, Akiyama, Tuuga, Majalap and Bernard2015) but the extent to which ungulates in Cambodian deciduous dipterocarp forests obtain minerals from waterholes is unclear and merits further research.

Importance of waterholes for large birds

Three of the four bird species studied, giant ibis, lesser adjutant and Asian woolly-necked stork, preferred deeper waterholes, whereas green peafowl had a preference for larger pool areas (Tables 3 & 4). Numerous studies have demonstrated that water depth influences foraging habitat of waterbirds (e.g. Colwell & Taft, Reference Colwell and Taft2000; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Cai, Li and Chen2010). In particular, fluctuation in water depth determines the accessibility of foraging habitat, which in turn provides a greater diversity of foraging habitats, thus supporting a greater diversity of waterbirds (Collazo et al., Reference Collazo, O'harra and Kelly2002; Stapanian & Waite, Reference Stapanian and Waite2003). Additionally, the density of waterholes within a 1-km radius around waterholes positively influenced utilization by giant ibis (Table 4). Giant ibis is a dry forest specialist, has the smallest global range of our target species and is restricted to deciduous dipterocarp forests (BirdLife International, 2017). The model for this species contained the most waterhole variables, suggesting a strong and specific association with waterholes during the dry season. Giant ibis is the only waterbird in our study that nests in deciduous dipterocarp forest during the wet season and this could be a factor in explaining its strong association with waterholes. However, wet season monitoring would be needed to assess any year-round dependence on waterholes. Waterhole utilization by green peafowl was related to pool size and waterhole size. Keo (Reference Keo2008), noted that as water levels fluctuate, pool size may play a major role in providing foraging habitat for large birds as well as grazers, particularly when resources are scarce during the dry season.

Waterhole size

Waterhole size (i.e. maximum area) positively influenced waterhole utilization by giant ibis, lesser adjutant, green peafowl and Eld's deer (Tables 3 & 4). Camera-trap photos (Plate 1) show these species foraging in a relatively wide area beyond the open water of the waterholes. Some species do not regularly drink from waterholes but will opportunistically forage at waterholes if available. We suggest larger waterholes may offer more foraging habitat, and also contain important microhabitats, including short grass, as well as both dry and saturated substrates. Furthermore, these microhabitats may provide primary food resources, including frogs, crabs and crickets, especially for giant ibis (Keo, Reference Keo2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake and Dolman2013a). As such, large waterholes are likely to be particularly significant for conservation in Cambodian deciduous dipterocarp forests; declines in large herbivore numbers, which probably play an important role in keeping waterhole areas open, could have significant knock-on effects on other biodiversity, including foraging waterbirds.

Anthropogenic factors

As predicted, most of the target species were more likely to frequent waterholes located further from human activity, in this case, villages (Table 4), possibly related to food availability as waterholes closer to villages are more likely to be harvested for fish (including eels) and frogs by local people (Keo, Reference Keo2008). This is supported by earlier studies that suggested the giant ibis foraged at waterholes further from human settlements because of the species’ sensitivity to disturbance (Keo, Reference Keo2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Collar, Lake, Vorsak and Dolman2012). However, further research is needed to determine whether the cause is human depletion of forage availability, persecution or other direct disturbance. The distribution and habitat use of banteng are also thought to be significantly affected by human disturbance (Pedrono et al., Reference Pedrono, Tuan, Chouteau and Vallejo2009; Gray & Phan, Reference Gray and Phan2011; Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Hedges, Pudyatmoko, Gray and Timmins2016). Eld's deer, however, is known to occur in areas with relatively high levels of human disturbance locally (e.g. Ang Trapeang Thmor, Cambodia, and Savannakhet Eld's deer sanctuary, Laos; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Brook, McShea, Mahood, Ranjitsingh and Miyunt2015a). However, both sites are small and have been the target of conservation outreach focused on Eld's deer. We suggest that these areas may be exceptional and that, more widely across the species’ range, Eld's deer will have been extirpated from many locations close to villages. The species’ small fragmented population in Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary is predominantly concentrated in the inner core of the protected area, perhaps a result of past hunting across most of the landscape (Loucks et al., Reference Loucks, Mascia, Maxwell, Huy, Duong and Chea2009). Our data did not show any relationship between green peafowl and distance to villages, but other studies have reported that green peafowl prefer to forage in areas further from human settlements (Brickle, Reference Brickle2002; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Zhang, Xie, Huang and Wen2008; Sukumal et al., Reference Sukumal, McGowan and Savini2015). It is possible that green peafowl in our study area were less affected by human disturbance compared to neighbouring Viet Nam, and less affected by resource competition at waterholes than other target species. However, peafowl are probably impacted by hunting, including egg harvesting, and capture for the pet trade (Goes, Reference Goes2009).

Management implications

Dogs and cattle were recorded at 24 of the 54 camera-trapped waterholes, accompanying people collecting water and fishing, and utilized the same resources used by our target species. Resource competition between local people and wildlife may therefore be of concern. Illegal hunting also poses a significant threat to these globally threatened species: we found illegal hunting gear (including snares) at waterholes. Snaring continues to be a major threat in South-east Asia's protected areas (O'Kelly, Reference O'Kelly2013; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Sreekar, Brodie, Brook, Luskin and O'kelly2016; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Hughes, Laurance, Long, Lynam and O'Kelly2018). The number of illegal activities detected around waterholes did not feature in any of the most supported models for any of our study species, but accurately recording levels of illegal activity within protected areas is difficult and it is likely that data from the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting System Tool, as used in our study, is biased in a number of unpredictable ways (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Solomon and Blank2009). In addition, there was an inadequate number of rangers (only 40–50 rangers working in the protected area of > 3,700 km2) and patrolling was probably not conducted at all the waterholes. However, our study provides baseline data for conservation and protected area management in this sanctuary.

Understanding the utilization of waterholes by globally threatened species is critical for wildlife conservation and protected area management given that the deciduous dipterocarp forests of eastern Cambodia are predicted to be impacted by anthropogenic climate change (Yusuf & Herminia, Reference Yusuf and Francisco2010). Modelling the impacts of drought on ungulate populations suggested that water stress could have negative impacts on sedentary and grazer species (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Chauvenet, McRae and Pettorelli2012), and maintaining sufficient water resources is a guideline for protected area management in such dry habitats (Bolduc & Afton, Reference Bolduc and Afton2004). Manipulation of waterholes, and rehabilitation of other water sources to retain rainwater, to improve habitat for wildlife during the dry period, are management tools that should be investigated for Cambodian deciduous dipterocarp forests (Kumar & Sahi, Reference Kumar and Sahi2009; Gray et al., Reference Gray, McShea, Koehncke, Sovanna and Wright2015b). However, prior to any large-scale manipulation, modification of waterholes should be in the form of a small- to medium-scale experiment, to test our theories about the benefits of manipulation. Provision of artificial waterholes can also mitigate negative human–wildlife interactions by preventing wildlife moving out of protected areas and exploiting water resources within villages or settlements (Dave, Reference Dave2010). Although deepening and enlarging of selected natural waterholes in suitable locations (such as those further from villages) could significantly enhance remaining dry forest habitat (Gray et al., Reference Gray, McShea, Koehncke, Sovanna and Wright2015b), this would have to be accompanied by additional law enforcement, as hunting remains the biggest driver of population declines of large mammals throughout Indochina (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Sreekar, Brodie, Brook, Luskin and O'kelly2016).

Acknowledgements

This research project was conducted as part of a master's degree that was financially supported by a WWF-EFN, Russell E. Train Fellowship, The Rufford Foundation, and USAID and Humanscale through WWF-Cambodia. We thank USAID and IDEA WILD for the provision of research equipment, including camera traps, WWF-Cambodia and Mondulkiri Provincial Department of Environment for logistical and fieldwork support, the Eastern Plains Landscape Project, WWF-Cambodia, which coordinated with Provincial Department of Environment, and the Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary manager for providing supporting documentation. Our research was conducted in the Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary with permission granted by the Mondulkiri Provincial Department of Environment under a MoU between the Ministry of Environment and WWF-Cambodia.

Author contributions

Project development: CP assisted by DN, TG, TS, RC and GG; data collection and analysis: CP with the assistance of DN; writing: CP assisted by DN, TG, TS, RC and GG.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Our research was carried out following the legal standards of Cambodia's Natural Protected Area law, and under the permission of the Ministry of Environment, Provincial Department of Environment, and with the necessary approvals from King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi.