Around the year 1880, mainly following the research work of the anthropologist Cesare Lombroso, the relationship between madness and artistic expression has started to investigate in Italy. These were the years in which psychiatric science was emerging through the consolidation of a network of provincial mental asylums, the creation of specialised journals, the constitution of the Italian Society of Psychiatry in 1873 and the organisation of many congresses in the field of psychiatry (Babini et al., Reference Babini, Cotti, Muniz and Tagliavini1982).

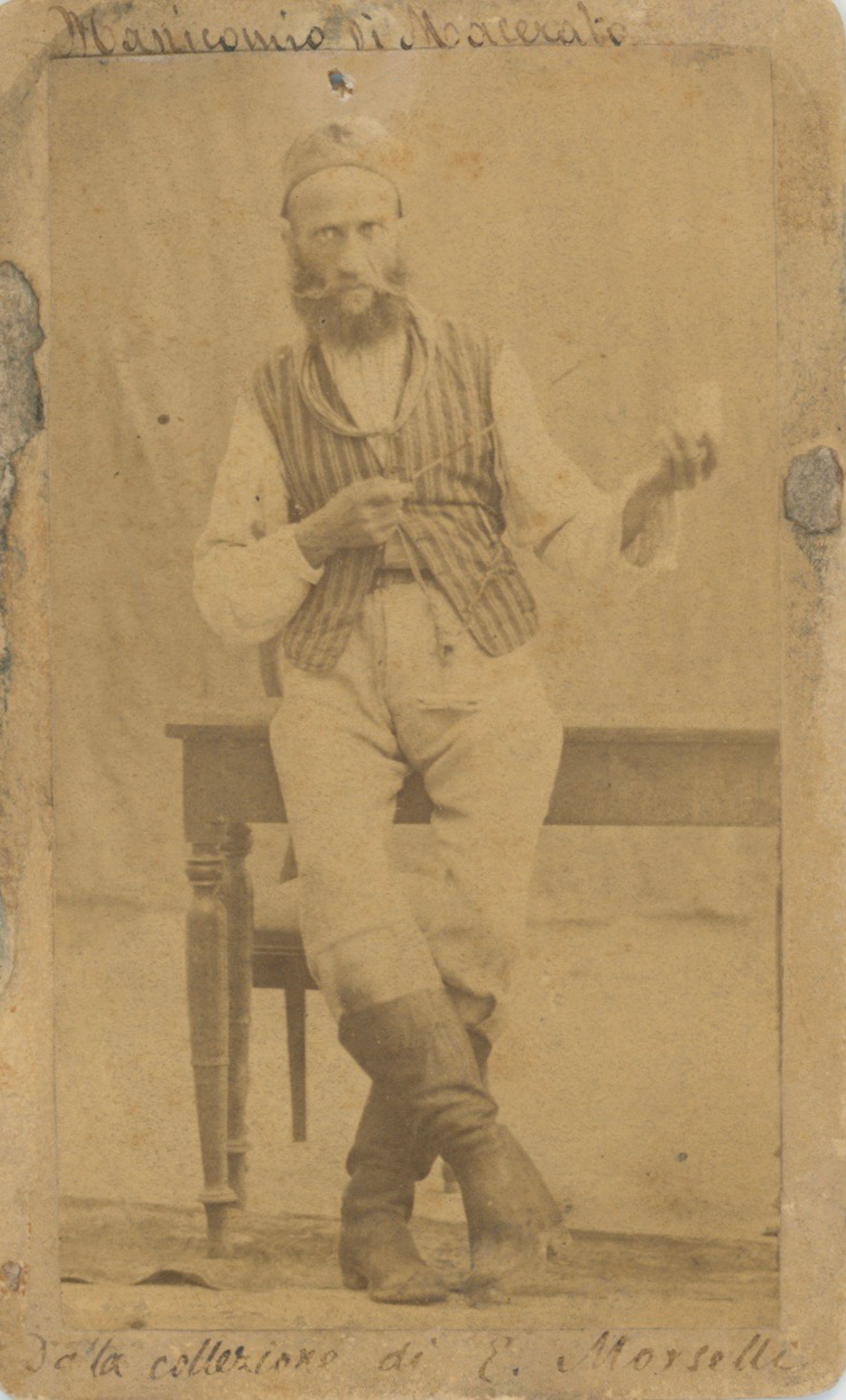

In 1880 in Reggio Emilia, during one of such congresses, the exhibition of psychiatry inaugurated. For the first time, directors of Italian psychiatric institutions publicly showcased the art works created by their patients. On that occasion, Cesare Lombroso and Maxime Du Camp analysed the creative works of ‘95 patients with artistic tendencies’ and published an article considered to be the first Italian review that dealt with the subject of artistic expression in psychiatry written with a clinical diagnostic perspective (Lombroso and Du Camp, Reference Lombroso and Du Camp1880). Enrico Morselli, the director of the Santa Croce mental asylum in Macerata, also attended the exhibition in Reggio Emilia and exhibited a small sculpture made by his patient Antonio Tolomei, a cabinetmaker, admitted to the institute since 1873 (Pettinari, Reference Pettinari2018). Given his reputation as a promoter of ergotherapy, Morselli encouraged Tolomei to dedicate himself to his carvings, providing him with tools. Through the years, Morselli analysed Tolomei's creations and eventually published an article on his observations and analysis of Tolomei's productions (Morselli, Reference Morselli1881). Starting around 1877 and up until the year of his death in 1903 in the asylum, Tolomei spent his days making numerous sculptures. Morselli's eventual successors at Santa Croce, Gianditimo Angelucci and Arnaldo Pieraccini, continued in his footsteps in supporting Tolomei's creative need of artistic expression.

Among the surprising works created by Tolomei, preserved in the special ‘hall of artistic works’ in the asylum, the most remarkable creation was the ‘table that turns by itself and speaks’, a table named by Tolomei in several autobiographical notes and reported in an notable publication of 1894.

Dated around 1888, the large circular polylobulated table, unfortunately lost, rests on three feet carved with three angels. The table was entirely conceived and built by Tolomei who embellished it with a mechanism of iron levers enabling the figurines to rotate while the architectural elements remained fixed. The ideational complexity of this artefact is truly astonishing since each sculpture of the table, both in its individuality and in relation to the other elements, has a precise symbolic narrative meaning, implying an overall intricate planning by its creator. In particular the device positioned at the centre of the table depicts a woman bringing the ‘colonnades of Spain’ or coins to a priest portrayed in a confessional. The reference is to an episode involving Tolomei unjustly accused of robbery prior to his internment. The representation of the sculptor's moment of internment at Santa Croce is represented on the opposite side of the table. In the centre of the table, around a metal boiler, statuettes of four brigands carved with small hammers in their hands are positioned. The activation of the mechanism of levers and inclined planes enable the hammers to move up and down and strike the boiler to produce a noise: according to Tolomei, this sound was ‘the warning to call for revolt’. Each sculpture of the table is therefore rich in real or imaginary narrative references to the author's life or to the age in which he lived.

Through sculpting Tolomei was able to create significant concrete works which would become the vehicle of expression of his ideas; these productions would preserve the memory of a past life and a present life at risk of dispersion, in a context of depersonalising confinement.

Some of Tolomei's works were photographed and studied in 1894 by Gianditimo Angelucci and Arnaldo Pieraccini. The two psychiatrists dedicated a publication to the artistic works created by the mental asylum patients of Macerata, increasing the Italian studies on the subject of psychiatry (Angelucci and Pieraccini, Reference Angelucci and Pieraccini1894). This pamphlet, so far little considered in the field, shows how in a small but important provincial psychiatric institution, the debate on the theme of ‘art and madness’ was very much alive and involved some of the most important Italian psychiatrists of the time. Furthermore, Antonio Tolomei's legacy reached beyond national borders. In 1919 a photograph of the table made its way into the hands of the German art historian and psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn, and is still preserved to this today in the archives at the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg.

About the author

Giulia Pettinari is an art historian, curator and freelance researcher specialised in the field of Italian Outsider Art. She is an experienced creative studio instructor and the co-founder of McZee, a cultural association based in Macerata. Her last publication is Intorno a un tavolo. Antonio Tolomei e altre storie del manicomio Santa Croce di Macerata (Affinità Elettive Edizioni, 2018).

Carole Tansella, Section Editor