The Ministry of Justice defines self-harm as ‘any act where a prisoner deliberately harms themselves irrespective of the method, intent, or severity of any injury’.1 Both self-harm and suicide are more common among prisoners compared with the general population.Reference Hawton, Linsell, Adeniji, Sariaslan and Fazel2–Reference Fazel, Benning and Danesh5 In the 12 months to September 2021, there were 52 726 recorded incidents of self-harm in English and Welsh prisons.6

Self-harm causes significant distress among prisoners, their families and prison staff, and has significant costs to the National Health Service and prison services.Reference Favril, Laenen, Vandeviver and Audenaert7–Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9 People who self-harm are at increased risk of physical and mental morbidity, premature mortality and suicide.Reference Herbert, Gilbert, Cottrell and Li10,Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Steeg11 The effective prevention and management of self-harm is an important aspect of national suicide prevention strategies and the Prison Service Competency and Qualities Framework.12,13

Experiences, perceptions and attitudes of clinical staff regarding self-harm

Self-harm is a common presentation to clinical services.Reference Clements, Turnbull, Hawton, Geulayov, Waters and Ness14 Although many healthcare professionals support people who self-harm, negative staff responses have been described across settings, including emergency departments, general medical and psychiatric environments.Reference Friedman, Newton, Coggan, Hooley, Patel and Rickard15–Reference Thompson, Powis and Carradice21 These reactions include feelings of irritation, anger and antipathy.Reference Saunders, Hawton, Fortune and Farrell22,Reference Patterson, Whittington and Bogg23 Healthcare staff may also hold more hostile attitudes toward people who self-harm compared with other patients,Reference Saunders, Hawton, Fortune and Farrell22 and lack confidence in supporting them, reporting feeling helpless and ill equipped.Reference Friedman, Newton, Coggan, Hooley, Patel and Rickard15,Reference Patterson, Whittington and Bogg23,Reference Smith24 These attitudes and feelings can arise from poor understanding, work stress, stigma, being personally emotionally affected from witnessing self-harm and psychological defence mechanisms.Reference Saunders, Hawton, Fortune and Farrell22,Reference Rayner, Allen and Johnson25

Negative staff attitudes toward self-harm can result in their hostility toward, and distancing from patients, poor empathy and stigmatisation.Reference Pompili, Girardi, Ruberto, Kotzalidis and Tatarelli26 This can affect quality of care, increase a person's risk of future self-harm and deter them from treatment and/or engagement with clinical services.Reference Pompili, Girardi, Ruberto, Kotzalidis and Tatarelli26–Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30 Conversely, demonstrating respect and kindness can diminish feelings of shame and instil hope,Reference Wiklander, Samuelsson and Asberg28 and potentially reduce self-harm.Reference Rayner, Allen and Johnson25

Aims and context of this research

Prisoners who self-harm interact with both healthcare and prison staff. Understanding the experiences, perceptions and attitudes of these staff is important in understanding the care delivered, and any facilitators or barriers to reducing self-harm in prison. Prison staff's experiences of managing self-harm may also provide insights into its effect on their well-being.

We aimed to systematically review the research literature to answer the question, ‘What are the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of prison staff regarding adult prisoners who self-harm?’. To the best of our knowledge, no prior review of this literature has been published.

Method

We sought to collate all relevant studies of prison staff's experiences of, and perceptions or attitudes toward, self-harm in prisons for adults. Since this study is a systematic review of previously published research, ethical approval was not necessary. The protocol for this review is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; identifier CRD42020190618).

Search strategy

Electronic databases (EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO and CINAHL) were searched on 24 April 2020 for relevant international literature. The search was restricted to articles published since the year 2000, to determine current, rather than historical, attitudes, perceptions and experiences of prison staff relating to self-harm. Search terms were agreed between authors and ‘exploded’ or searched as MESH terms, to identify further relevant terminology (Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.70). Grey literature was additionally consulted on 18 May 2020, including reviewing the first 100 outputs from Google and Google Scholar, searching the Open Grey database, and reviewing relevant organisations websites such as The Howard League, Ministry of Justice, Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody, and Prison Reform Trust (Supplementary Appendix 2). Reference lists of relevant studies were hand searched.

Criteria for inclusion were as follows: participants were staff of any role or grade, working within prisons for adults, whose experiences of, perceptions of, or attitudes toward, self-harm were assessed with any quantitative or qualitative method. The Ministry of Justice definition of self-harm was used.1 All studies must have been published in the English language. All publication types were considered except for expert opinion papers, systematic reviews and editorials. Studies conducted exclusively in juvenile correctional settings and young offender institutes (YOIs) were excluded unless they provided data specific to staff's experiences with adult prisoners. This is because age is an influencing factor in determining staff attitudes toward self-harm,Reference Cleaver, Meerabeau and Maras31 and staff working in YOIs often manage both adolescents and adults. Studies conducted in secure mental health facilities or community settings were additionally excluded.

Study selection and quality assessment

Following the deletion of duplicates and non-English texts, all articles were independently screened for eligibility by two authors (T.H. and K.K.). Any disagreements regarding the exclusion of articles were resolved by consulting a third reviewer (L.R.), who made the final decision. The quality of each study was also independently assessed by two authors, using the following standardised quality appraisal tools: the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist for qualitative studies (T.H. and Z.B.);32 the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Observational, Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies (T.H. and L.R.)33 and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for mixed-methods study designs (T.H. and K.G.).Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman and Cargo34 Overall quality ratings of good, moderate or poor were assigned to each study. Any disagreements regarding quality ratings were resolved by discussion to achieve consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis: qualitative data

A standardised template was designed to collect relevant data from eligible studies. Relevant qualitative data from all studies were imported verbatim into NVivo 12 for Windows software (QSR International, Ltd., Australia; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home), and independently analysed by two authors (T.H. and Z.B.).35 A thematic synthesis was performed with inductive methods, whereby codes were derived directly from the data.Reference Thomas and Harden36 Each line of text was read, interpreted and coded according to its content and meaning. All codes were then compared between authors and analysed for similarities and differences. The codes were subsequently amalgamated into hierarchical themes, and new codes were created to group initial codes together. Final broad themes were agreed by both authors and interrogated by a third author (K.G.).

The small number of quantitative studies and the heterogeneity of methodology used between studies precluded the use of meta-analysis. Instead, a narrative synthesis of quantitative data was conducted following the framework described by Petticrew and Roberts.Reference Petticrew, Roberts, Petticrew and Roberts37 Studies reporting quantitative data were initially categorised by types of outcome measure and the specific aspects of staff's experiences or perceptions of, or attitudes towards, self-harm being examined. Within-study analysis was conducted by describing the main findings from each study and significant methodological aspects. Cross-study synthesis was subsequently performed by summarising the overall results and similarities or differences between studies, and taking account of variations in research design.

Results

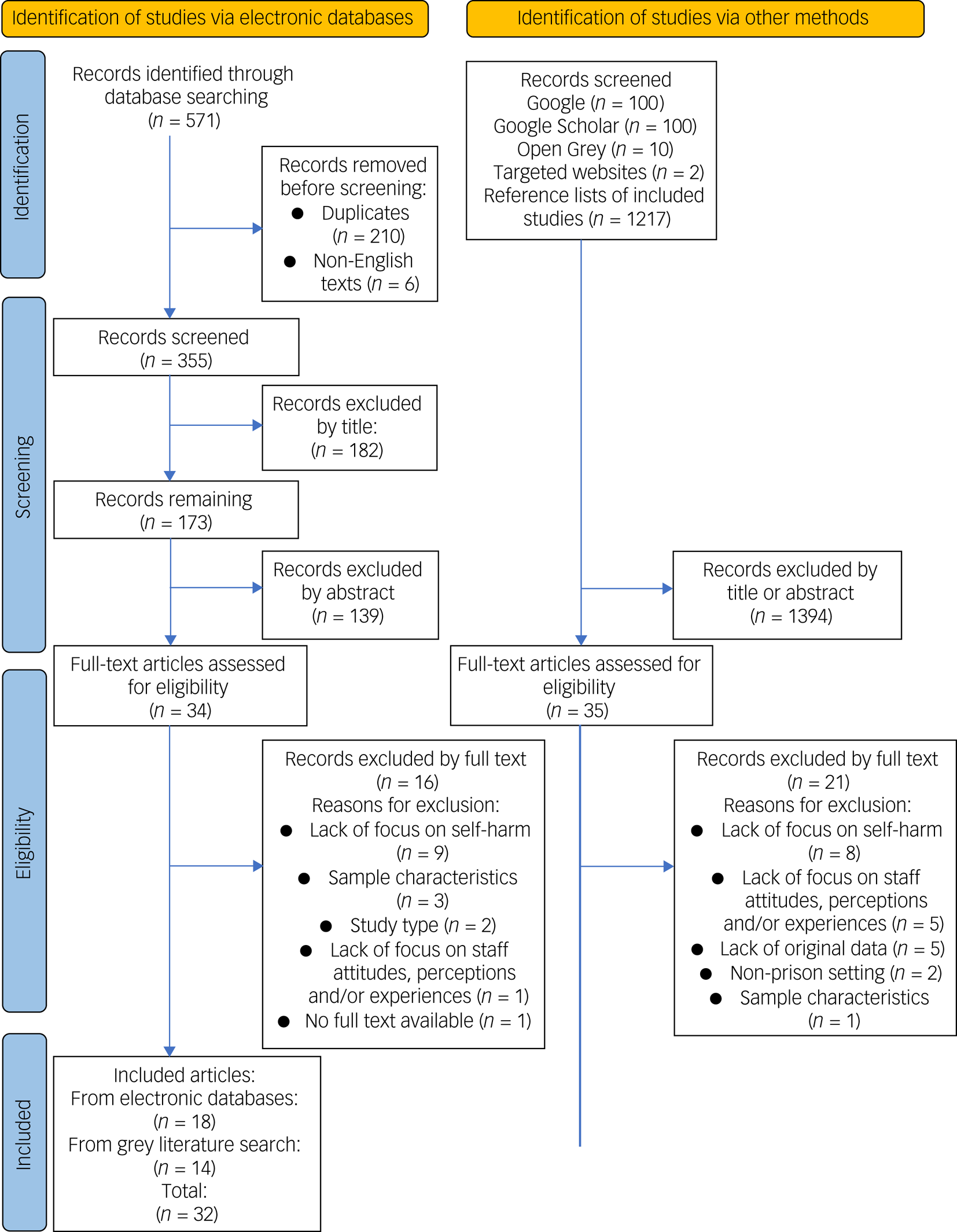

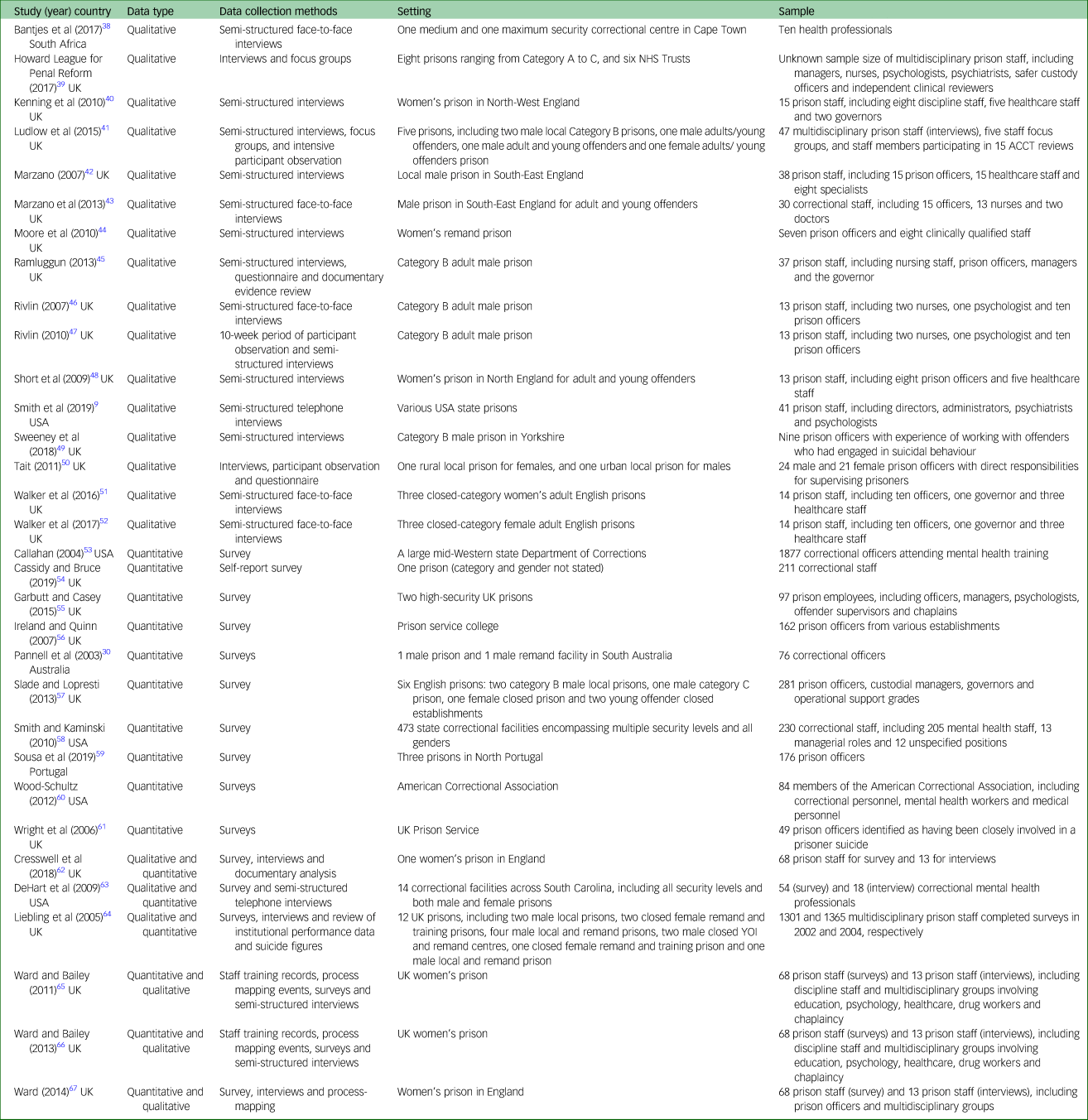

A total of 571 articles were identified from electronic databases and 1429 articles were retrieved from other sources (n = 2000) (Fig. 1). Following removal of duplicates and non-English texts, 1784 articles were screened by title and abstract. The full texts of 69 articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 32 met criteria for inclusion in the review (Table 1). Reasons for the exclusion of articles are detailed in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1 Summary characteristics of included studies

NHS, National Health Service; ACCT, Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork processes; YOI, young offender institute.

Studies included in the review

Of the 32 studies included, most were conducted in the UK (n = 24). Other countries represented included South Africa (n = 1), the USA (n = 5), Australia (n = 1) and Portugal (n = 1). Seventeen studies collected qualitative data, nine collected quantitative data, and six used mixed methods. Although most studies (n = 21) utilised mixed samples of professional groups working in prisons, seven focused exclusively on prison officers and two included only health professionals. In two studies, ‘prison staff’ were referred to without specifying which group/s this included.Reference Cassidy and Bruce54,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 The total number of participants across all studies, accounting for duplicate samples, equalled 6389 prison staff, although one study did not report sample size.39

Qualitative data synthesis

Twenty two papers containing qualitative data were included in the review. Four broad themes and 12 subthemes emerged from the analysis.

Theme 1: prison staff's experience of preventing and managing self-harm

Subtheme 1.1: high frequency and variety of self-harm in prisons

Witnessing a high frequency of self-harm was reported by prison staff in seven studies, described as occurring ‘all the time’ and ‘every time’ staff complete shifts.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Marzano42–Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63

‘I would say frequently, so every time I have a session at the prisons, there is at least one person that exhibits such behaviour or ideation’ (Officer).Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38

Staff witnessed numerous types of self-harm, with cutting being the most mentioned.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Marzano42–Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63

Subtheme 1.2: staff's perceived capacity and ability to manage self-harm

Despite the high frequency of self-harm witnessed, prison staff frequently expressed low confidence in understanding, preventing and managing self-harm.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49 This resulted in them feeling ‘helpless’ and ‘useless’, particularly if the self-harm was repetitive.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41–Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

‘There was nothing, I mean, you could do for him, I mean, make(s) you feel sort of useless’ (Healthcare staff).Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43

To improve their confidence and skills, many prison staff highlighted a need for more self-harm training,Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel51,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward and Bailey65,Reference Ward67 although some emphasised learning ‘on the job’.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

‘The [prison officer's] frustrations are they don't get it [self-harm], and I think if you help and guide them and help them get it, or at least help them understand why that is, it becomes less anxiety provoking for them and for the women then as well’ (Unspecified staff role).Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel51

Various occupational factors hindered staff's perceived abilities to care for self-harm. Inconsistent and insufficient staffing was felt to interrupt consistency of care and limit the identification and management of relevant risk factors. Staffing problems also reduced opportunities for multidisciplinary input for prisoners who self-harm, and decreased the time available for staff–prisoner engagement.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

‘Staffing is the main issue for it all. Suicide rates would come down if there was more staff … ’ (Officer).Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49

Staff described various challenges caring for people who self-harm in prisons, which were portrayed as ‘anti-therapeutic’ and ‘punitive’ settings.Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Staff frequently reported tensions between their ‘security’ and ‘care’ responsibilities, and the prison ‘regime’ was positioned as taking priority over healthcare.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Tait50,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 In contrast, in one establishment with low rates of self-harm, staff felt that their roles of ‘carer’ and ‘security officer’ were well integrated.Reference Rivlin46,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47 A prison culture was sometimes reported whereby staff felt shamed from outwardly expressing concern for prisoners who self-harm,Reference Marzano42,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 although this was less apparent among female staff.Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

‘There is (.) stigma attached to being a, ehm, a care bear, they call them in here – in the Prison Service – officers who care too much … ’ (Officer).Reference Marzano42

Staff generally felt more confident and able to manage self-harm when working in multidisciplinary teams. This allowed them to draw on broad skills and knowledge, resolve prisoners’ issues more quickly and achieve greater consistency of care.39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Cassidy and Bruce54 However, staffing and communication difficulties sometimes prevented effective teamwork, in addition to conflicting team perspectives and complex team structures.Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63

Subtheme 1.3: emotional effects of self-harm on prison staff

Numerous reactions to self-harm were described by prison staff, varying from frustration and feeling attacked to feeling ‘sad’ and ‘touched’.Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Tait50,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Many staff reported stress, anxiety, ‘burnout’ and ‘exhaustion’, which negatively affected their attitudes and care toward prisoners.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 Some staff felt ‘traumatised’ from witnessing self-harm and developed features of post-traumatic stress disorder,39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Ward67 and others reported that they became clinically depressed and self-harmed themselves.Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49

‘They [prison staff] used to phone me up at home in floods of tears because they kept hearing a prison chewing through her skin, and that's all they could hear’ (Governor).Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52

Many staff were fearful of being blamed or punished for prisoners’ self-harm, especially in Coroner's court.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67

‘ … Nobody wants to get entirely involved in such a situation. Just in case that person try and hang themselves. Nobody wants to be taken to the coroner's inquest … ’ (Healthcare staff).Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43

Various coping strategies for dealing with the emotional effects of self-harm were described. Some staff viewed self-harm pragmatically as ‘part of the job’.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52 Perceiving suicide as a rational ‘choice’ or ‘determined effort’ was suggested to allay feelings of guilt and responsibility.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63 Other coping strategies included using humour,Reference Marzano42,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49 taking ‘time out’ following incidents,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52 seeking support from colleagues39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63 and maintaining a good work–life balance.Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52 Some staff described maladaptive coping methods, such as alcohol intake and avoidance behaviour.Reference Marzano42,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Tait50,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52

Staff frequently reported needing more practical and emotional support from managers, including greater positive recognition for effectively dealing with self-harm and less emphasis on ‘the failures’.39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Tait50,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Several support mechanisms were described including post-incident debriefs and access to formal medical support, but many staff avoided engaging with formal support systems.39,Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52 This was because of concerns about preserving their masculinity, confidentiality and avoiding being touched by stigma, as well as perceptions that accessing support represents weakness or poor coping.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Ward67 Staff also felt that opportunities for support following self-harm incidents were limited by pressures to maintain their duties and ‘keep the regime going’.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ward67

‘The whole ethos in this prison seems to be IT'S HAPPENED. GET OVER IT. CARRY ON because we've got to, we've got to let them out for feeding or, or exercise, or something’ (Officer).Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43

Theme 2: attitudes and perceptions of prison staff regarding self-harm

Subtheme 2.1: perceived risk factors for self-harm

Mental disorder was reported as a risk factor for self-harm by prison staff across 12 studies.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40–Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62–Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67 Substance misuse was most commonly mentioned,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 although some staff referred to psychosis, schizophrenia, depression and personality disorder.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48 Mental disorder was frequently associated with repeated self-harm,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Marzano42,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Ward67 and seen as being more legitimate or ‘genuine’ relative to other risk factors.Reference Marzano42,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62 When self-harm was associated with mental disorder, prison officers often felt incapable of adequately supporting the prisoner.Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38,Reference Marzano42,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48

‘You'll find for the prolific self-harmers that they've got mental issues … ’ (Officer).Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48

Negative childhood experiences and/or past abuse were highlighted as risk factors for self-harm by prison officers and healthcare staff.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Marzano42,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48 Staff across several studies recognised stressors within prison environments including boredom, isolation, loneliness, bullying and borrowing between prisoners,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38–Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward and Bailey66,Reference Ward67 which some officers viewed as self-inflicted, illegitimate reasons for self-harm.Reference Marzano42

‘It's like, you are doing that [self-harm] because you are, you are moaning about your situation. But you put yourself in that situation … Take responsibility. Take responsibility for your actions, and just deal with it. Deal with your time’ (Officer).Reference Marzano42

Arrival into prison was described as a particularly vulnerable period,39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67 along with status change from remand to convicted and receiving very short or long custodial sentences.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42 Other recognised risk factors included aggression, receiving bad news, bereavement, domestic, family and financial stressors, low self-worth and recent negative experiences.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference Ward67

Subtheme 2.2: perceived reasons for self-harm

The most frequently reported reason for self-harm by multiple staff roles was to ‘manipulate’ others.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Bantjes, Swartz and Niewoudt38–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62–Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67 Prison staff listed benefits that ‘manipulative’ self-harm aimed to achieve, including more relaxed prison regimes; access to goods, medications, care or services; transfer to hospital and escape from other inmates.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 In contrast, some staff felt that self-harm was an expression of needs and/or a ‘cry for help’.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Marzano42,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67 Other commonly perceived functions of self-harm included ‘attention-seeking’,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67 emotional expression and relieving tension,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40–Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 and a coping mechanism for difficult experiences.Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40–Reference Marzano42,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67

‘ … Cutting yourself and seeing the blood oozing out is a much more visual representation of a relief of tension than talking to somebody’ (Healthcare staff).Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40

Some staff described ‘copycat’ self-harm where inmates replicated that of others, Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 and reported prisoners being encouraged to harm themselves by peers and ‘less-seasoned staff’.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Other described functions of self-harm included providing empowerment or control,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Ward67 giving enjoyment including sexual pleasure,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Marzano42,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 and punishing oneself.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ward67

Subtheme 2.3: relationships between self-harm and suicide

Non-fatal self-harm was often seen as distinct from and unrelated to suicide.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44 Prison staff acknowledged that self-harm could result in death, but felt this was a result of ‘determined misadventure’ or going ‘too far’ and not a ‘genuine suicide attempt’.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Some prison staff believed that suicide was unpreventable, stating that ‘if someone's determined to kill themselves, they'll always find a way’.Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 It was frequently suggested that prisoners who intend to die use more lethal self-harm methods and conceal their intentions and distress more than those with non-suicidal motives.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44

‘He set fire to himself in the exercise yard, he'd hung himself, he'd scratched his wrists, but he's more of a nuisance than an active suicide risk, but on this occasion, he went too far’ (Unspecified prison staff).Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

Theme 3: factors affecting staff attitudes toward self-harm

Subtheme 3.1: effects of repetitive self-harm

Repeated self-harm was viewed most negatively by prison staff, and often regarded as being fundamentally different from isolated incidents.Reference Marzano42–Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Repetitive self-harm was described as ‘draining’ staff patience, optimism and resources, and was associated with critical comments, perceived ‘attention-seeking’ and staff frustration.Reference Marzano42,Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Although some staff identified that ‘ongoing’ interactions with prisoners who repeatedly self-harm made them feel closer to them, many officers and healthcare staff reported that this was desensitising and reduced their empathy.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45

‘So when he does it, any gesture, it's very hard to go oh, my god, it's really so so wrong and (.) poor thing kind of [ … ] when you sort of, for the seventh time gone taken him to hospital, treated the wound, and (.) I think it just set this relation can go a bit stale’ (Healthcare staff).Reference Marzano42

Subtheme 3.2: effects of gender

Male staff more frequently recommended maintaining emotional distance from prisoners, whereas females emphasised relationship building.Reference Ward67

Male prisoners were thought to self-harm more severely and discreetly, generally afforded less sympathy and deemed to have less ‘genuine’, ‘serious’ or ‘complex’ issues relative to females.Reference Marzano42,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63 Prison staff occasionally portrayed self-harm as childish and emasculating, commenting that it was ‘such a young female kind of thing to do’.Reference Marzano42,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

Subtheme 3.3: effects of job role

Healthcare staff generally reported a greater understanding of self-harm compared with prison officers. They more often identified situational risk factors within prison environments,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48 commented on the effects of childhood trauma and abuse,Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9 and recognised self-harm as a coping mechanism for emotional distress.Reference Marzano42 They also generally reported feeling more able to prevent self-harm.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41 Compared with prison officers, healthcare staff less frequently delineated perceived ‘genuine’ and ‘non-genuine’ self-harm,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48 and less often directly described self-harm as ‘manipulative’ or being enacted to punish staff.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45

Compared with prison officers and healthcare staff, staff in specialist roles, such as governor, chaplaincy and suicide prevention coordinator, demonstrated more concern for the management of repetitive self-harm, more frequently emphasised its underlying causes and more frequently conceptualised people who self-harm as victims.Reference Marzano42

One study found no variation in levels of expressed emotion toward self-harm between staff roles.Reference Moore, Andargachew and Taylor44

Theme 4: the effects of prison staff's experiences, perceptions and attitudes on self-harm management and prisoner interactions

Subtheme 4.1: labelling and dichotomising self-harm

Prison staff frequently dichotomised self-harm as being either ‘genuine/real’ or ‘non-genuine’ based upon their perceived functions of the behaviour. ‘Manipulation’ and ‘attention-seeking’ were typically labelled as ‘non-genuine’ illegitimate reasons for self-injury,Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 and less severe ‘superficial’ self-harm injuries were more likely to be perceived as ‘non-genuine’.Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48

‘They are just attention seekers, they are taking away from the real problem, people who have real problems … ’ (Officer).Reference Marzano42

Self-harm that was labelled ‘non-genuine’ or ‘manipulative’ was often regarded as less deserving of care and intervention, and some prison staff reported resisting opening ACCTs (Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork processes used in England and Wales to assess and manage self-harm risk) on these prisoners.Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Staff also described ‘manipulative’ and ‘non-genuine’ self-harm as requiring more punitive management, such as isolation, boundary setting and reduced staff attention.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 This contrasted to staff descriptions of optimal self-harm management, which generally involved building strong staff–prisoner relationships, getting to know individual prisoners and an emphasis on communication, rapport building and trust.Reference Smith, Power, Usher, Sitren and Slade9,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel51,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64,Reference Ward67

‘The ones that I feel genuinely do have real problems and a genuine self-harm issue. I don't mind spending time with people who genuinely need help. I can't be doing with timewasters … ’ (Officer).Reference Kenning, Cooper, Short, Shaw, Abel and Chew-Graham40

Staff in one study recognised that patients whose self-harm is ‘non-genuine’ may also be struggling and require support.Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48

Subtheme 4.2: staff protecting themselves from the effects of prisoner self-harm

Staff commonly reported ‘building up tolerance’, and becoming ‘desensitised’ or ‘hardened’ to self-harm following repeated exposure.39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41–Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 They additionally described maintaining emotional distance and becoming emotionally ‘switch[ed] off from prisoners’.39,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward67 These were generally construed as effective defence mechanisms to limit the emotional effects of self-harm and reduce burnout among prison staff. However, they were also thought to be associated with poorer risk identification and management, and intolerance, anger and cynicism toward prisoners.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42

‘ … It would not affect me one way or another who or how many die through self-harm’ (Healthcare staff).Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

Fear of being blamed for prisoners’ self-harm promoted defensive practices among prison staff. Staff described avoiding involvement in self-harm incidents, such as by avoiding night shifts and/or contact with prisoners who frequently self-harm.Reference Marzano42,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Tait50 Staff also reported refraining from using personal discretion and adopting risk-averse practice to protect themselves.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano, Adler and Ciclitira43,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 There were tensions described between healthcare and prison staff, whereby prison officers were reluctant to accept responsibility for caring for people who self-harm, particularly repetitive self-harm, and attributed this role to healthcare professionals,Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 whereas healthcare staff felt that officers should assume greater ownership.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ramluggun45

‘They could stop self-harming becoming medicalised, by giving some sort of responsibility back to your discipline officers. All decisions seemed to be made by healthcare, which should really not be the case’ (Nurse).Reference Ramluggun45

Subtheme 4.3: staff adherence to self-harm policies and procedures

To reduce intense workload and circumvent a lack of resources, staff described deviating from recognised self-harm policies and procedures. For example, although some staff reported having low thresholds to commence ACCT procedures and following them by the letter,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel52 others were discouraged by their colleagues from opening ACCTs,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62 resisted doing so and/or waited for others to accept this responsibility.Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41 This was because of the perceived strain on staff time of completing multiple paperwork, which was felt to subtract from meaningful engagement with prisoners.39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Walker, Shaw, Hamilton, Turpin, Reid and Abel51,Reference Ward67 Similarly, some staff recognised the importance of individualising self-harm management, whereas others treated self-harm processes as ‘tick-box’ tools.39,Reference Ludlow, Schmidt, Akoensi, Liebling, Giacomantonio and Sutherland41,Reference Marzano42,Reference Sweeney, Clarbour and Oliver49,Reference Ward67 Prison officer attitudes and trust/distrust of specialist staff roles influenced the availability and effectiveness of multidisciplinary support for prisoners at risk of self-harm; for example, affecting the extent of specialist input during risk assessment and case reviews.Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

Quantitative data synthesis

Ten studies used quantitative methods alone,Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Callahan53–Reference Wright, Borrill, Teers and Cassidy61 and six mixed methods.Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62–Reference Ward67 All 16 studies used surveys to obtain quantitative data relevant to this review.

Trauma Symptom Inventory

Two studies used the Trauma Symptom Inventory,Reference Briere, Elliot, Harris and Cotman68 tool to examine self-reported post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among UK prison staff.Reference Cassidy and Bruce54,Reference Wright, Borrill, Teers and Cassidy61 Cassidy and Bruce found that 31.8% of prison staff closely involved in prisoner suicide in the past year reported clinical-level symptoms of PTSD.Reference Cassidy and Bruce54 Furthermore, Wright et al discovered PTSD symptoms reported by 36.7% of prison officers, and that experience of prisoner suicide predicted such symptoms.Reference Wright, Borrill, Teers and Cassidy61

Attitudes towards Prisoners who Self-Harm Scale

Two UK studies administered the Attitudes towards Prisoners who Self-Harm Scale (APSH) to prison staff, one in two high security prisons and one to prison officers attending prison service college training.Reference Garbutt and Casey55,Reference Ireland and Quinn56 This self-report scale measures attitudes relating to self-harm.Reference Garbutt and Casey55 In both studies, staff achieved similar mean scores, both indicating generally positive attitudes, but some negative attitudes present.Reference Garbutt and Casey55,Reference Ireland and Quinn56 Among prison officers attending Prison Service College, positive attitudes toward the treatment of prisoners, as measured by the General Attitudes towards Prisoners Scale (ATP), significantly predicted more favourable attitudes toward self-harm.Reference Ireland and Quinn56 Female staff scored statistically significantly higher on the APSH than males in the same study, indicating more positive attitudes.Reference Ireland and Quinn56 Staff's perceptions of prisoner's behavioural characteristics significantly influenced attitudes toward self-harm, with less positive attitudes toward ‘disruptive’ compared with ‘well-behaved’ prisoners.Reference Ireland and Quinn56

Another study administered the APSH and ATP to 176 prison officers in three Portuguese prisons.Reference Sousa, Gonçalves, Cruz and de Castro Rodrigues59 High proportions of prison staff believed that self-harm served ‘attention-seeking’ and ‘manipulative’ purposes and that prisoners who self-harm will not commit suicide. The majority of prison officers recognised self-harm as a coping mechanism. Perceptions of self-harm being ‘manipulative’ were more common among female officers, whereas male officers were significantly more likely to relate prisoner's self-harm to previous experiences of abuse. There was a significant positive correlation between prison officer's abilities to understand prisoners’ feelings and their understanding of self-harm. Officers that endorsed the strict discipline of prisoners were more likely to believe that prisoners who self-harm should be harshly treated and/or ignored, although this view was not shared by the majority.

Studies using statistical methods to analyse prison staff's attitudes, perceptions or experiences of self-harm

Five studies used quantitative methods to analyse factors affecting prison staff's experiences or perceptions of, or attitudes toward, self-harm.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30,Reference Callahan53,Reference Slade and Lopresti57,Reference Wood-Schultz60,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64

Slade and Lopresti utilised linear regression to examine factors associated with staff–prisoner relationships and staff resilience among 281 multidisciplinary UK prison staff and 169 community controls.Reference Slade and Lopresti57 They found that 61.2% of staff witnessed self-harm serious enough to warrant medical attention on ten or more occasions, which was associated with significantly less friendliness, understanding and support between staff and prisoners. More accepting attitudes toward suicide were predictive of better staff–prisoner relationships, along with staff members’ use of ‘surface acting’ and ‘deep acting’ emotional labour. Surface acting refers to the suppression of true feelings and/or presenting emotions that are different from those being felt, e.g. faking sadness and empathy. Deep acting, on the other hand, involves attempting to feel emotions that are deemed most appropriate, such as attempting to experience genuine empathy, rather than superficially faking this. Greater staff resilience was predicted by greater experience of prisoner suicide, advanced suicide prevention training, working in male prisons with low suicide and high self-harm rates, and greater deep acting and less surface acting of emotions. Staff in women's prisons perceived suicide as more preventable, displayed less condemning attitudes and reported less ‘faking of emotions’ compared with staff in men's prisons.

Wood-Schultz examined the effects of personal attitudes on the quality of suicide prevention responses by 84 prison officers, mental health and medical staff from the American Correctional Association.Reference Wood-Schultz60 Positive attitudes toward prisoners were significantly associated with increased quality of suicide prevention responses among all staff, whereas attitudes toward death and suicide were not predictors.

A study of 76 correctional officers in Australia presented staff with vignettes depicting self-harm and asked them to rate causes and functions of the behaviour.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30 Officers frequently linked self-harm to poor coping, depression and drug misuse. Other highly reported functions of self-harm by officers included ‘crying for help’, attention-seeking and releasing emotions, whereas suicidal functions were least frequently recognised. In contrast with evidence from qualitative studies,Reference Marzano42–Reference Ramluggun45,Reference Short, Cooper, Shaw, Kenning, Abel and Chew-Graham48,Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 the severity and repetitiveness of self-harm did not significantly alter staff perceptions of its cause and function; however, low severity non-repetitive self-harm was linked by staff to prisoner distress, and higher severity self-harm was more often perceived as suicidal.Reference Pannell, Howells and Day30

A study of 1877 security staff in the USA investigated staff experiences and views of mental illness and healthcare in prisons, using clinical vignettes and self-administered surveys.Reference Callahan53 Male and minority ethnic staff were significantly more likely to view prisoners, depicted in clinical vignettes, as at risk of self-harm. Prisoners were also more likely to be deemed at risk of self-harm if officers perceived their problems as caused by mental illness, chemical imbalance or genetics instead of ‘bad character’.

Staff and prisoner surveys and interviews, and participant observation, were used in UK prisons to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of a programme to reduce self-harm and suicide.Reference Liebling, Tait, Durie, Stiles and Harvey64 Multiple staff across several prisons reported finding self-harm management ‘extremely stressful’, and many strongly agreed that further training and support were required. Improved quality of life of prison staff was significantly associated with greater effectiveness of suicide prevention and suicide prevention effectiveness correlated highly with strong communication, good work culture, appropriate staff roles and responsibilities, and positive working relationships with managers. In prisons where many staff perceived self-harm as manipulative and threatening their authority, higher levels of prisoner distress existed.

Studies reporting descriptive statistics

Six studies reported the proportion of prison staff describing particular experiences, perceptions and attitudes relating to self-harm.Reference Smith and Kaminski58,Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63,Reference Ward and Bailey65–Reference Ward67

Four papers used data collected from the same sample of 68 multidisciplinary prison staff in the UK, using questionnaires.Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Ward and Bailey65–Reference Ward67 The most commonly perceived reasons for prisoner self-harm included emotional expression, exerting control and gaining attention;Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Ward67 75% of prison staff thought that self-harm served to ‘manipulate’ others.Reference Cresswell, Karimova and Ward62,Reference Ward67 Mixed views were expressed regarding staff's perceived knowledge of self-harm, with this being presented as both a strength and a challenge;Reference Ward and Bailey65–Reference Ward67 43% of prison staff reported needing more self-harm training, and lack of time was reported by 70% of staff as limiting optimal care.Reference Ward and Bailey65–Reference Ward67

In a survey of 54 mental health professionals across 14 secure facilities in the USA, 91% of those working in prison viewed self-harm as a means to seek special treatment or transfer of location,Reference DeHart, Smith and Kaminski63 85% of staff viewed self-harm as a stress-coping mechanism, and a minority attributed self-harm to suicidal motives or severe mental disorder. Only 4% of mental health professionals could not recall a self-harm incident in the previous 6 months.

In a survey of 230 mental health professionals across 473 USA correctional facilities,Reference Smith and Kaminski58 98% of staff knew a prisoner who self-harms in prison. The most witnessed method was scratching/cutting with objects, which generated the most concern among staff.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment found that seven studies were good quality, 15 were moderate quality and ten were poor quality (Supplementary Appendix 4). Common study limitations included small sample sizes, non-random sampling, use of non-validated self-report measures and lack of information regarding the delivery and structure of staff interviews. All studies were cross-sectional in design, which prevented assessment of changes in staff experiences, perceptions and attitudes over time, and the ability to make causal inferences on identified associations.

Interrater reliability scores for the quality assessment of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies in this review were 87.5%, 90% and 83.3%, respectively, which increased to 100% following consensus between independent reviewers.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 32 papers from five countries that provided data to answer the research question, ‘What are the experiences, perceptions and attitudes of prison staff regarding adult prisoners who self-harm?’. Both qualitative and quantitative data showed that prison staff report frequent exposure to many types of self-harm, and have a broad range of both positive and negative attitudes and perceptions regarding this. Perceptions that self-harm is ‘manipulative’, ‘non-genuine’ or ‘attention-seeking’ were associated with descriptions of poorer quality care and hostile behaviour toward prisoners in several qualitative studies, particularly for repetitive self-harm. Similarly, quantitative data revealed associations between prison staff's attitudes and perceptions, and the quality of their suicide prevention responses, self-harm management strategies, staff–prisoner relationships and levels of prisoner distress. Staff demonstrating positive attitudes and good understanding of self-harm described greater empathy and supportive management of prisoners. Several staff in qualitative studies reported experiencing intense emotions and distress from self-harm incidents, and found it difficult to manage self-harm within prisons; these emotions influenced their reported interactions with prisoners and capacity to care. The effects of self-harm on prison staff were similarly recognised in quantitative data, where multiple prison staff expressed symptoms of PTSD.

Many of the attitudes and experiences described by prison staff have been demonstrated in other settings, e.g. among hospital workers. These include strong emotional reactions to self-harm, positive and negative staff attitudes and behaviours, feelings of uncertainty and inadequacy, and a perceived lack of time and resources to effectively care for self-harm.Reference O'Connor and Glover69 A specific challenge of self-harm management in prisons is the reported tensions between balancing security, justice and punishment with compassionate healthcare, which creates confusion and conflict among prison staff. This tension of ‘care versus custody’ is well-recognised in the forensic literature.Reference Mills, Kendall, Mills and Kendall70

It is important to consider how prison staff's perceptions and attitudes are perceived by prisoners. In prior research, prisoners who self-harm have described prison staff as ‘approachable’, helpful and providing strong emotional support.Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference Ward and Bailey65,Reference Ward and Bailey66 They have also highlighted the beneficial effects of positive relationships and conversations with prison staff to alleviate distress.Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference Ward and Bailey65,Reference Ward and Bailey66 In contrast, some studies have reported prisoner views that they are not adequately listened to or cared for following self-harm, and that prison staff lack understanding of this.Reference Marzano42,Reference Rivlin, Shuker and Sullivan47,Reference Ward and Bailey65,Reference Ward and Bailey66 Prisoners who self-harm have also reported fears of being labelled ‘attention seekers’, and beliefs that less dangerous self-harm receives less concern and support from staff.Reference Ward and Bailey65 Perceptions of inadequate care and hostility from prison staff have been reported by prisoners to increase their risks of self-harm.Reference Marzano42,Reference Ciclitira and Adler71 Prison staff's descriptions of intense workloads and lack of resources are echoed in prisoner reports of finding prison staff ‘too busy’ and not ‘geared up’ for managing self-harm.Reference Marzano42

It is notable that prison staff described feelings and emotions that might mirror those experienced by prisoners who self-harm, such as feeling ‘helpless’ and ‘frustrated’. Prison officers often requested mental health training, which might include helping them to understand their own reactions to self-harm, in turn potentially improving emotional well-being.

Many of the risk factors and reasons for self-harm identified by prison staff in this review are corroborated by previous research.Reference Power, Brown and Usher72–Reference Favril, Yu, Hawton and Fazel74 Several of these risk factors are unique to prisons, such as isolation and boredom from excess time in cells and bullying and violence between prisoners. Prison staff's descriptions of inmates ‘copying’ self-harm are supported by ‘clustering’ of self-harm incidents in prisons across time and location.Reference Hawton, Linsell, Adeniji, Sariaslan and Fazel2 It is therefore suggested that self-harm management strategies extend beyond individuals, to other prisoners in the locality.Reference Hawton, Linsell, Adeniji, Sariaslan and Fazel2,Reference Pope75

Prison staff frequently underestimated the association between self-harm and suicide, as self-harm strongly predicts subsequent suicide, both in prison and following release.Reference Humber, Webb, Piper, Appleby and Shaw76,Reference Fazel, Cartwright, Norman-Nott and Hawton77 Furthermore, perceived ‘manipulative’ reasons for self-harm among prisoners can co-exist with suicidal intent and lethal behaviour,Reference Dear, Thomson and Hills78 which is out of keeping with staff views that ‘manipulative’ self-harm requires less intervention. These misconceptions, particularly around the risk of subsequent suicide, demonstrate an important training need.

This review highlights the significant demands on prison staff that routinely face high rates and numerous types of prisoner self-harm. Staff often perceived themselves to lack training and skills to prevent and manage self-harm, and fear blame and feel unsupported by the prison system. According to the job demand–control–support modelReference Karasek and Theorell79 and job demands–resources model,Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli80 this imbalance between high demands and perceived lack of control, support and resources can create a predisposition to occupational stress. Furthermore, witnessing self-harm and suicide can be traumatising in itself.Reference Bell, Hopkin and Forrester81 This could partly explain the high rates of occupational stress and mental illness within the prison workforce.Reference Kinman, Clements and Hart82,Reference Finney, Stergiopoulos, Hensel, Bonato and Dewa83 In the studies reviewed, many prison staff described coping by becoming emotionally distanced from prisoners and desensitised to self-harm; this might suggest compassion fatigue, whereby a person's ability to provide empathetic care declines following exposure to traumatic events.Reference Sinclair, Raffin-Bouchal, Venturato, Mijovic-Kondejewski and Smith-MacDonald84 Improving prison officer support would likely not only improve staff well-being and retention, but also indirectly improve care for prisoners.

Implications for clinical practice and service improvement

Reducing self-harm in prisons requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the individual needs of prisoners, the attitudes and perceptions of prison staff, and the prison environment. In accord with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, all prison staff in contact with people who self-harm should receive appropriate training.85 This training should identify and challenge any negative attitudes and perceptions, and support staff in developing more positive attitudes through education and reflection. Caring attitudes and empathy should be reinforced through positive recognition, whereas labelling self-harm as ‘non-genuine’ and punitively treating prisoners risks their safety and should be actively discouraged. Many prison staff in this review felt that current training was insufficient, suggesting a need to involve staff in co-designing training and identifying their learning needs. Ensuring recognition of the strong association between self-harm and subsequent prisoner suicide should be an important aspect of staff training.

Prison services should also ensure effective policies for tackling bullying, boredom, isolation and substance misuse, all of which were identified to precipitate self-harm. Having sufficient resources, including adequate staffing and access to specialist mental health teams, is vital to prisoner safety. Risk management systems, such as ACCT processes, can improve the quality of care delivered to prisoners who self-harm;Reference Humber, Hayes, Senior, Fahy and Shaw86 however, staff engagement with these processes varied in the present review, highlighting the roles of clinical governance and audit to monitor their effectiveness and address barriers to effective implementation.

Prison services should work collaboratively with staff to design and implement support structures that are accessible and acceptable to the workforce, and that are actively prescribed. Stress management and coping skills training for dealing with the emotional effects of self-harm could improve staff well-being and compassion. Good working relationships and role clarity are protective for prison officer well-being.Reference Kinman, Clements and Hart82

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and mixed-methods synthesis focussing on the experiences, perceptions and attitudes of prison staff working with prisoners who self-harm. The review included a large sample of many staff roles within prisons, and identified several facilitators and barriers to self-harm management and prevention, with clear implications for research and policy. Furthermore, the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative data allowed a detailed understanding of the extent and nature of the review findings.

Limitations of this review include the high level of heterogeneity between studies, which precluded meta-analysis. The frequent use of self-report measures and non-validated questionnaires to measure staff's attitudes and perceptions meant that several studies were of low quality. The generalisability of the review findings is limited by the exclusion of non-English language articles and underrepresentation of studies conducted outside of the UK. Excluding studies conducted in YOIs was important to ensure that staff attitudes, perceptions and experiences regarding self-harm related to adult, rather than adolescent, prisoners; however, this means that some information regarding young adults who self-harm may have been excluded from the review. All included studies were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has significantly affected self-harm within prisons, as well as prison environments, staffing levels and staff well-being.6,Reference Hewson, Green, Shepherd, Hard and Shaw87–Reference Johnson, Gutridge, Parkes, Roy and Plugge89

Future research

Reviewing the perspective of prisoners would be useful to allow a detailed understanding of how staff attitudes are perceived, and might affect self-harm. Future research is also needed to unpick potential associations between rates of self-harm in prisons and the attitudes, perceptions and well-being of prison staff. The overall quality of research in this area would be strengthened by larger sample sizes and validated measures for assessing prison staff attitudes and beliefs about self-harm. Longitudinal studies are also needed to assess how staff attitudes and behaviours are developed over time. Future research should additionally investigate the effects of COVID-19 on self-harm in prisons. Data from England and Wales indicate that rates of self-harm have increased for female prisoners but decreased for male prisoners during the pandemic.6

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.70

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Olivia Schaff, Clinical Librarian at Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, for their support conducting electronic database searches.

Author contributions

All authors meet all four ICMJE criteria for authorship and reviewed the final manuscript. T.H. conceptualised and designed the systematic review, developed the search strategy, screened articles, conducted data extraction and analysis, conducted quality appraisals of included studies, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. K.G. conceptualised and designed the systematic review, conducted and supervised data analysis, conducted quality appraisal of included studies, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Z.B. conducted data extraction and analysis, conducted quality appraisals of included studies, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. K.K. developed the search strategy, screened articles, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. L.R. conceptualised and designed the systematic review, screened articles, conducted quality appraisals of included studies, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.