INTRODUCTION

As Afghanistan falls into Taliban rule and many thousands of people are fleeing for safety, the Biden administration has put the United States Department of Homeland Security in charge of efforts to resettle people who worked for the U.S. military or other U.S. organizations.Footnote 1 Ensuring that the most deserving, those who worked on behalf of the U.S., are rescued is a highly fraught and complex task. Applicants for immigration benefits will face “extensive vetting,” including questions about their occupations over the past decades of U.S. occupation and, prior to that, Taliban rule.Footnote 2 The U.S. will be vigilant about trying to prevent Taliban sympathizers from entry. Meanwhile, those once employed by the U.S. who remain in Afghanistan face terrifying threats. It is becoming very clear that having taken a job with the “wrong side” during decades of armed conflict can carry enormous consequences, both for those who remain at home and those who attempt to enter countries of refuge.

In a period of U.S. policy-making characterized by hostility to noncitizens, few categories of people seeking immigration benefits have been targeted as explicitly and firmly by law as those who affiliated with violent groups in their home countries. The U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) restricts immigration benefits to those associated with a terrorist group, as well as anyone who committed war crimes, genocide, or other crimes labeled with “moral turpitude” (I.N.A. 212(A)(3)). The broad scope of these restrictions and their contemporary application means that there is an ever-widening net into which hopeful immigrants originating from war zones may be entangled before being excluded. There is also a growing bureaucracy dedicated to finding immigrants already in the U.S. who may have committed human rights abuses abroad, and a multinational enforcement regime designed to crack down on those who are imagined to be escaping accountability in their countries of origin by seeking safe haven within the borders of liberal democratic states (Reference Rowen and HamlinRowen & Hamlin, 2018; Hamlin & Rowen, 2020).

Despite these powerful legal prohibitions, denying or revoking immigration benefits to individuals who are affiliated with human rights violations, particularly terrorism, is not a simple process. These decisions involve highly nuanced judgment calls about culpability and freedom of action during episodes of mass violence. Far from being an obscure area of law, such judgments are increasingly commonplace in the American immigration landscape. And yet, this kind of nuance is not present in policy debates or public opinion research about immigration. This omission presents an opportunity to expand our understanding of how the public views such morally fraught questions of immigration law, particularly as the U.S. considers its obligations to individuals fleeing violence from the end of US occupation.

To this end, our research question focuses on what the American public thinks about the deservingness of applicants for refugee status who are affiliated with organizations that have committed human rights abuses abroad. We ask whether and how public opinion takes a different view of low-ranking affiliates of such an organization, compared with individuals who had higher-ranking roles. In their decisions and in their reasoning, do most Americans support the extremely broad net cast by “No Safe Haven” policies? Or do they think about applicants' deservingness differently depending on the particulars of an individual case?

These are important questions in light of the growing acknowledgement that nonstate actors, including NGOs and the general public, can play an important role in influencing policies toward human rights (Reference BracicBracic, 2016; Reference Bracic and MurdieBracic & Murdie, 2020; Reference McEntire, Leiby and KrainMcEntire et al., 2015). Given the rapid growth of restrictive immigration policies, policymakers in receiving states may assume that the public prefers these strict policies. However, we have surprisingly little information about what the American public actually thinks of providing immigration benefits to individuals fleeing violence but who were also somehow connected to violence in their home countries. Our study therefore provides opportunities to think about the practical political space for less restrictive immigration policy options, using a study that probes respondents about the ways in which law is implemented.

To introduce our empirical puzzle, we provide background on the policies and case law that casts a wide net of exclusion over individuals affiliated with human rights abuses, and specifically terrorism, abroad. We then explain how criminal law logics on culpability, particularly international criminal law logics, as well as social psychology studies on moral blameworthiness, complicate simplistic understandings of deservingness in the immigration context. Next, we place our empirical concerns in the context of prior public opinion research, which has mostly focused on a different set of questions about which groups deserve immigration benefits. Finally, we present results from a public opinion study of a nationally representative sample of Americans, taken before the fall of Afghanistan to Taliban rule yet illustrating pressing questions for current policy. Our study embedded a survey experiment in the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) to assess attitudes toward immigration benefits for applicants who worked in different positions in a Taliban prison camp, as well as open-ended questions to examine the underlying logics people invoked to explain their decisions.

We find that even in this particularly fraught case (providing immigration benefits to individuals who worked for a group known to harbor terrorists that harmed Americans), much of the American public identifies complexities associated with immigration decision-making. A majority of respondents did not want to immediately deny immigration benefits to a low-level Taliban worker who otherwise met refugee visa requirements; instead, they preferred to either grant the visa or remained undecided, often seeking further information about the case. Looking at respondents' explanations, we find two distinct clusters of reasons that we classify as either circumstantial–focused on the particularities of the case–or categorical–focused on general attributes of the applicant. Circumstantial explanations were more commonly associated with low-level workers. Further, many people using circumstantial reasoning saw a distinction between the jobs potential immigrants have done in their pasts and what they actually believe, underscoring the fraught dynamics of armed conflict in which people may be swept up in violence they do not support.

The increasing convergence of criminal law and immigration law usually disadvantages immigrants. However, in this instance, we find that public concerns about culpability for wrongdoing commonly associated with a criminal justice framework, which cares about actions and intentions as well as roles and responsibilities, can lead to a more generous attitude toward immigrants affiliated with human rights violations than current policies allow. These findings highlight the challenge of determining which immigrants from war-torn countries should be offered immigration benefits, complexities that law and policy related to denying safe haven should better consider.

Implementing “No Safe Haven”

Current law and policy leave little room to consider why a person may have worked for a terrorist organization, or what role they played. Instead, the idea that human rights violators and international criminals should not receive immigration benefits in the liberal democracies of the Global North has developed into a massive international policy regime aimed at both preventing the entry of suspected human rights violators into popular immigrant destinations, and identifying and removing those who manage to enter (Hamlin & Rowen, 2020).Footnote 3 Domestic immigration law declares that applicants for asylum in the United States are ineligible if they have participated in the persecution of others or if they have engaged in terrorist activity.

While immigration lawyers and advocates have been decrying the rigidity of both the persecutor bar and the terrorism bar for many years, these restrictions have only gotten stricter over time. The persecutor bar dates back to the aftermath of the Second World War, and was originally designed by Congress to prevent people who had participated in Nazi atrocities from gaining safe haven in the United States. The Supreme Court further clarified the scope of this bar in the case of Federenko v. U.S. (449 U.S. 490, 1981), which focused on the fact that the defendant was captured by Nazis and forced to work in a concentration camp. The Supreme Court ruled that being part of the Nazi organization, even against his will, and omitting that fact, is a material misrepresentation which disqualified him from U.S. immigration benefits. Further, a 2020 decision by Attorney General Barr clarified that the evidentiary burden is not on the government to show that an applicant has persecuted others. Rather, Barr ruled that if the Department of Homeland Security claims that the persecutor bar applies, the applicant must prove “by a preponderance of the evidence” that it does not apply to them or be excluded.Footnote 4

In addition to the persecutor bar, a more recent development in American immigration law is the terrorism bar, developed in the 1990s, but greatly expanded in the aftermath of 9/11. Section 219 of the INA now stipulates that any foreign organization that the U.S. State Department Bureau of Counterterrorism deems to have threatened the national security of the United States will be classified as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO). Any person who is a member of, or who has provided “material support” to a FTO is ineligible for immigration benefits. Much like with the persecutor bar, the scope of the terrorism bar is very broad. Material support has been defined in the law as any effort that sustains or maintains a terrorist organization, even in the most minimal way. For example, in 2018, the Board of Immigration Appeals concluded that a woman who had been forced to cook and clean for a Salvadoran guerilla group had provided material support and was therefore ineligible for immigration benefits.Footnote 5

In theory, the Secretaries of the Department of State or Homeland Security, in consultation with the Attorney General, can authorize a “situational” waiver for an applicant who provided material support to an FTO. This is a process that exists through either statutory exception or executive exemption.Footnote 6 However, recent research suggests that the standard for a “material support” exception or exemption is now more restrictive than even the 2001 Patriot Act contemplated (Reference LeeLee, 2019, p. 382). In practice, the threshold requirements for the statutory exception are nearly impossible to meet, and there is no clear procedure for the executive exemption (Reference LeeLee, 2019, p. 380). In Fiscal Year 2014, the only year for which previous research found publicly available data, 40,000 people applied for a waiver, and only 19 were granted (Reference LeeLee, 2019, p. 386). It appears that both the statutory exception and executive branch exemption exist primarily on paper. And, for the specific case used in this study, there is no statutory exception for supporting a designated terrorist organization such as the Taliban.

As these bars to migration have expanded and crystallized, so have U.S. efforts to identify people to whom the bars might apply. Over the past two decades, the Department of Homeland Security has borrowed from both domestic and international criminal law to develop a detailed set of screening questions to determine whether an applicant for immigration benefits might be excludable under the persecutor or terrorism bars. Both the I-589 form (for internal asylum applicants) and the I-590 form (for overseas refugees) contain detailed questions about the applicant's past residencies, work experience, and involvement in organizations. Part B of the I-589 asks if the applicant or any of their family members have “ever been in or been associated with any organizations or groups” in the applicant's home country, including seemingly innocuous and even appealing groups such as student groups or human rights groups, as well as more controversial groups such as military or paramilitary, civil patrol or guerilla organization. Despite the restrictive application of the rules, there is a space to explain the level of involvement, leadership roles, and length of time involved. Other application questions involve acts beyond membership in particular organizations, asking whether the applicant, spouse, or children ever ordered, incited, or otherwise participated in causing harm or suffering to someone else on account of their membership in a protected group. This question mirrors definitions of international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanities, and war crimes, and illustrates how screening practices complement enforcement practices to exclude or remove perpetrators of these crimes (Reference Rowen and HamlinRowen & Hamlin, 2018).

Rather than ban individuals based on where they are from, these questions aim to identify what the applicants may have done. At the same time, these questions are broad, casting a wide net over individuals who were even loosely affiliated with organizations engaged in violence. We do not know how many otherwise-eligible applicants for immigration benefits are screened out each year based on U.S. government assessments about their past actions and affiliations. However, we do know that this method of immigration restriction is expanding rapidly. Individuals affiliated with human rights violations abroad face growing and often insurmountable barriers to accessing or retaining US immigration benefits, with little room to consider their particular roles or responsibilities in the violations.

Dilemmas of deservingness in immigration law

Under No Safe Haven policies, individuals connected with violence abroad may not be directly blamed for specific acts of violence. However, as with other restrictionist immigration policies, the US government has decided they are not deserving of benefits because of their proximity to violence. These policy developments implicate numerous socio-legal literatures, including the converging logics of criminal law and immigration law, as well as law and psychology studies about attributions of blame for legal transgressions. Both sets of literatures provide initial insights into public opinion about whether someone affiliated with human rights abuses deserves immigration benefits, a question that has yet to be studied.

Domestic crimmigration

A growing body of domestically-focused scholarship highlights how criminal law logics have come to dominate the enforcement of immigration law, reinforcing restrictive policies based on categorical assessments of immigrants as either criminals or potential criminals (Reference StumpfStumpf, 2006, Reference Hernández and CuauhtémocGarcía Hernández, 2018). One of the key features of this phenomenon that scholars have called “crimmigration” is the focus of enforcement efforts on immigrants who are cast as having violated domestic criminal laws while inside the United States. There is less scholarly attention paid toward the growing restriction of individuals who may have violated domestic or international laws while in their home countries, a subject that also implicates international criminal law.

During the twenty-first century, the U.S. immigration bureaucracy has made it a priority to remove so-called “criminal aliens,” or noncitizens who have been convicted of a crime in the United States. By expanding the number of crimes which make noncitizens eligible for deportation, the U.S. has used criminal law to widen the scope of its immigration enforcement (Reference Beckett and EvansBeckett & Evans, 2015). Notably, both sides of the American political spectrum have participated in the increased visibility of the “criminal alien”: conservatives have tried to paint most noncitizens with the criminal brush, while liberals have at times advocated for deserving immigrants such as DREAMers by contrasting them with lawbreakers imagined as less deserving (Reference Abrego and Negrón-GonzalesAbrego & Negrón-Gonzales, 2020; Reference LaubyLauby, 2016; Reference ToshTosh, 2019).

The strategic use of criminal frames for immigrants reflects a broader societal tendency to blame marginalized groups for domestic social and political ills, coupled with categorical assessments that have little to do with their substantive claims for immigration benefits. Labeling individuals as immigrants and/or criminals and making them targets of punitive attitudes can serve to sharpen the moral and social distinction between those who are more or less “deserving” of either public condemnation or support (Reference GansGans, 1995, p. 7; see also Reference Reiter and CoutinReiter & Coutin, 2017). As far back as the 1990s, immigrants were framed as potential criminals with a particular concern for “system abuse” and “fraud” in gaining benefits (Reference Pratt and ValverdePratt & Valverde, 2002, p. 144). In earlier eras, immigration restrictions were explicitly racist and predicated on biological notions of purity (Reference TichenorTichenor, 2002); current regulations are tied more closely to national stereotypes and culture (Reference Massey and PrenMassey & Pren, 2012; Reference MullenMullen, 2001; Reference Pratt and ValverdePratt & Valverde, 2002). People seeking immigration benefits who are presented as “morally corrupt” and “criminals” overshadow images of the deserving refugee and victim of human rights violations (Reference Pratt and ValverdePratt & Valverde, 2002, p. 146).

While crimmigration theories typically focus on the social construction of immigrants as domestic or even transnational criminals, concerns about foreign human rights violations implicate international criminal law, with its own logics about culpability (Reference Rowen and HamlinRowen & Hamlin, 2018). International criminal law builds from domestic criminal law principles of personal responsibility, legality (specifically nullum crimen sine lege, nullum poena sine lege or “no crime without law, and no punishment without law”), and fair labelling, which contribute to the general logic that people deserve outcomes consistent with their individual acts and intentions (Reference RobinsonRobinson, 2008). Yet, international criminal courts try to distinguish between individuals based on their roles and responsibilities, not only their acts and intentions. This approach reflects the distinct factual context of mass atrocity where distinguishing perpetrators, victims, and bystanders is challenging, if not impossible (Reference DrumblDrumbl, 2007; Reference MartinezMartinez, 2007).

Beyond practicality, there are ethical and moral reasons to focus on roles and responsibilities in mass violence and avoid assigning blame to low-level offenders, particularly when blame is based on categorical assessments. Domestic criminal law seeks to punish individuals who are deviant; however, during mass violence, not participating can be deviant (Reference DrumblDrumbl, 2007). Low-level perpetrators are under both social and institutional pressure to follow superior orders to commit acts that may be considered violations of international law (Reference van EliesSliedregt, 2007; Reference SmeulersSmeulers, 2019). Prosecuting leaders ensures that courts do not ascribe criminal liability for heinous acts that an organization's members did not intend or foresee, and avoids collective guilt for entire groups based on categories such as ethnicity or nationality (Reference van BethSchaak, 2008; Reference RobinsonRobinson, 2008; Reference RobinsonRobinson, 2017).

While it is clear that punishing perpetrators of international crimes is distinct from withholding immigration benefits, both involve beliefs about blameworthiness and deservingness during mass violence. The tensions between international and domestic criminal law suggest that the convergence of criminal law and immigration law may lead to “guilt by association,” an ever-widening net into which applicants from countries experience violence may find themselves trapped and unable to access immigration benefits.

Evaluating blameworthiness and deservingness

Despite a robust literature on psychological processes related to blameworthiness and deservingness in the criminal law context, there is less research on how those beliefs map on to the immigration context. In criminal law, fact-finders focus on whether a person is blameworthy for a particular act and deserves punishment, and are supposed to consider character only in limited circumstances.Footnote 7 In immigration law, there is a specific mandate to consider character; “good moral character” is part of an applicant's eligibility for benefits.Footnote 8 Character and acts may be distinct, but judgments about one often inform judgments about the other, particularly when the issue at hand is blameworthiness for wrongdoing.

Research at the intersections of law and psychology point out that notions of blameworthiness and deservingness are intuition based, stemming from one's experience rather than being “studied reason based” (Reference SolanSolan, 2003, p. 1003). In deciding whether someone is more or less blameworthy, motivated reasoning reflects an emotional reaction to an event, which may be shaped by proximity to it and/or identification with the victims or perpetrators (Reference SolanSolan, 2003, p. 1025). In particular, blaming in the criminal law context involves attributions of other people and their intentions, with particular regard to whether the person poses a threat to society (Reference NadlerNadler, 2012, p. 1). Empirical research on how mock jurors determine guilt or innocence, for example, reveals that peoples' explanations often focus on concerns about the person's character, which is closely tied to beliefs about their motives, rather than (or in addition to) their particular actions (Reference AlickeAlicke, 1992; Reference Nadler and McDonnellNadler & McDonnell, 2012). Interpretations of motives shape attributions of blameworthiness and, by extension, criminal culpability.

Attributions of blame and deservingness in the criminal context provide initial insights into attributions that may occur in the immigration context, and the challenges that can arise without due process protections designed to disaggregate beliefs about who a person is (i.e., character), what they did (i.e., act), and why (i.e., motive). Reference SoodSood (2013, 312) suggests that individuals use a “motivated justice” model in which they focus on information they deem relevant to deciding wrongdoing within a given legal rule. This finding underscores the potential collateral psychological effects of legal rules that cast a wide net. Another important mechanism underlying attributions of blame has to do with causation, as individuals consider factors such as intentions and foresight (Reference Lagnado and GerstenbergLagnado & Gerstenberg, 2017, p. 587; Reference SolanSolan, 2003). Reference AlickeAlicke (2000) suggests that attributions of blame relate to beliefs about whether the accused had control over the situation. Similarly, people may decide a person or group is not blameworthy because they did not have control over a situation's outcome (Reference Alicke, Buckingham, Zell and DavisAlicke et al., 2008; Reference Nadler and McDonnellNadler & McDonnell, 2012, p. 39).

Notably, criminal law tries to minimize the effects of these psychological processes to guide judgments based on the acts with which defendants have been charged. Criminal law seeks to avoid judgments about blameworthiness for a particular act solely on a particular person's morality, or “the kind of person one is” (Reference LeonardLeonard, 2001, p. 452). Fact-finders are supposed to pay attention to the circumstances related to the act, and avoid categorical condemnation of certain “kinds of people.” One challenge in criminal law is to make sure that fact-finders do not conflate information about motive or the accused's mental state with information about the accused's character, as assessments about motives and mental state are often necessary for assessments of criminal culpability (Reference Nadler and McDonnellNadler & McDonnell, 2012).Footnote 9 In other words, fact-finders are supposed to avoid inferences that rest on the strength or weakness of moral character, even when making inferences about motive and the accused's mental state.

Procedural protections to limit a fact-finder's consideration of character and enhance focus on a person's acts and motives are nonexistent in immigration law, where assessments of character are part of the fact finder's determination of eligibility. In particular, when applicants go through the process of refugee status determination, the decision-maker first makes a finding of credibility and, relatedly, character, before moving to the question of fit with the legal definition of a refugee.Footnote 10 However, even if they are deemed credible, individuals may be subject to exclusion by “No Safe Haven” policies' that lump together people who are affiliated with violence abroad.

Unlike juries, the public do not literally judge these applications for immigration benefits. Still, governments respond to whether their actions are implicitly or explicitly supported by the public (Reference BracicBracic, 2016). We have little understanding of whether, in cases of judgment about immigration benefits for those affiliated with human rights abuses abroad, the public focuses on factors such as individual roles and responsibilities, other individuating circumstances, or similarly fuses beliefs about character, motives, and actions based on group affiliation.

Understanding deservingness through public opinion research

Public opinion research is critical to understanding whether restrictionist immigration policies such as “No Safe Haven” have popular support, or whether such support is merely assumed by policy-makers. Our question helps illuminate whether individual applicants are perceived according to the specific circumstances and actions that are legally relevant to their particular case, or evaluated on group membership or affiliations. This is a complement to prior research, which has focused on understanding why people oppose or support immigration writ large (Reference Hainmueller and HopkinsHainmueller & Hopkins, 2015), often treating immigrants as an undifferentiated aggregate category (Blinder, 2015).

When studies have differentiated between types of migrants, they have usually drawn categorical distinctions based on economic status or identity-based factors rather than examining individuals' roles or behaviors. For example, opposition to immigration can be rooted in perceptions of immigrants as competitors in the labor market (Reference Espenshade and HempsteadEspenshade & Hemshade, 1996, Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and WongCitrin et al., 1997, Reference Scheve and SlaughterScheve & Slaughter, 2001), or as a fiscal burden on the state (Reference Facchini and MaydaFacchini & Mayda, 2009; Reference Gerber, Huber, Biggers and HendryGerber et al., 2017). Public opinion consistently prefers immigrants with more formal education or higher status job skills, a categorical assessment of their economic value (Reference Hainmueller and HiscoxHainmueller & Hiscox, 2010; Reference Turper, Iyengar, Aarts and van GervenTurper et al., 2015).

Other prominent strands of research attribute anti-immigration attitudes to prejudice or “cultural threat,” which also focuses on categorical assessments of migrants. In such views, majority-group citizens are more likely to oppose immigration when they associate it with differences along racial, ethnic, religious, or linguistic lines (e.g. Reference FordFord, 2011; Reference Hainmueller and HopkinsHainmueller & Hopkins, 2015; Reference Heath and RichardsHeath & Richards, 2020; Reference QuillianQuillian, 1995). Ethnicity and religion can be linked to security-related threats as well (Reference Hellwig and SinnoHellwig & Sinno, 2017), including in the post-9/11 US context (Reference Haner, Sloan, Cullen, Graham, Jonson, Kulig and AydınHaner et al., 2021). Taken together, these works reinforce the argument that public opinion distinguishes among immigrants primarily on the bases of economic status and group identities (Reference EssesEsses, 2021; Reference Hainmueller and HopkinsHainmueller & Hopkins, 2015).

Recently, public opinion research has been more attentive to the subgroup of immigrants categorized as refugees (e.g. Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and HangartnerBansak et al., 2016, Steele & Abdelaaty, 2019, Reference Abdelaaty and SteeleAbdelaaty & Steele, 2020). Under both international law and the domestic laws of receiving states, people who are eligible for refugee status are fleeing persecution and can therefore be associated with vulnerability, crisis, and security risk. Studies focused on refugees have found that, in both the U.S. and Europe, public support is greater for people who are characterized as refugees (viewed as politically motivated) as opposed to migrants, who are viewed as economically motivated (Reference Hainmueller and HopkinsHainmueller & Hopkins 2015; Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and HangartnerBansak et al., 2016; Reference Verkuyten, Mepham and KrosVerkuyten et al., 2018; Reference Hager and VeitHager & Veit, 2019; Reference Rasmussen and PoushterRasmussen & Poushter, 2019; Reference HamlinHamlin, 2021). This difference holds even when both groups are portrayed in survey experiments as equally vulnerable, because of the conceptual link between deservingness and political victimization, not economic necessity (Reference HamlinHamlin, 2021, Reference de D.Coninck, 2020).

However, in explaining attitudes toward this subset of migrants, most scholarship has remained focused on the same categorical factors that emerged in the prior literature on general immigration, with little attention to the distinct legal and normative issues associated with asylum and refugee law. In a striking mismatch with legal or policy-based thinking, public support shifts based on asylum applicants' characteristics that are legally irrelevant to refugee status, such as demographics (gender, age), economic value (previous occupation), and other characteristics (religion, language fluency) that might trigger “cultural threats” (Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and HangartnerBansak et al., 2016; Reference Esses, Hamilton and GaucherEsses et al., 2017). As with other migrant categories, potential refugees who are viewed as more economically valuable and less culturally threatening are more likely to gain public approval. In the US case, for example, public support increases for hypothetical applicants who are Christian and fluent in English, and who had previous employment as a doctor or teacher; in contrast, public support decreased for applicants who were Muslim, spoke little or no English, and had worked as farmers (Reference Adida, Lo and PlatasAdida et al., 2019). Cross-national studies find that similar factors are associated with attitudes toward both immigrants and refugees, whether it is attitude-holders' prejudice and feelings of threat (Reference NassarNassar, 2020) or refugees' origins and economic status (Reference de D.Coninck, 2020).

There are some exceptions to these general findings about who is seen as deserving of refugee status. For example, features of individual cases that increase vulnerability seem to create additional sense of deservingness: Europeans are more likely to support admitting asylum applicants who have experienced torture, lost family members, or suffer from PTSD (Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and HangartnerBansak et al., 2016). Other work shows that individuals' narratives matter: exposure to refugees' personal narratives created greater support for Somali refugees in Kenya (Reference Audette, Horowitz and MichelitchAudette et al., 2020). Individuating information can work in both directions, however: elites' messages about the costs and benefits of acceptance also swayed Turkish public support for Syrian refugees, for better or worse (Reference Getmansky, Sınmazdemir and ZeitzoffGetmansky et al., 2018).

Despite these recent salutary developments in experimental research, the literature remains overwhelmingly focused on immigrants' characteristics rather than their individual circumstances. As a result, we know very little about whether members of the public care about the distinctions that are legally relevant to determining the validity of an individual asylum claim. The questions that emerge in this study remain largely unexamined: how might members of the public respond to the particulars of an individual application for legal status that triggers No Safe Haven laws and policies? Do their choices about who to admit–and their reasoning about those choices–support existing restrictionist immigration law and policy? Do people's reasoning reflect logics behind domestic and international criminal law that focus on acts, intentions, roles, and responsibilities? Or, are they simply making decisions on the basis of the same factors that shape attitudes toward immigrants in the aggregate, without regard for the legal framework related to No Safe Haven?

Data and methods

To assess American public opinion about individuals who have been affiliated with human rights violations abroad, we embedded a survey experiment in a module of the 2018 CCES. The CCES was a survey of 60,000 U.S. resident adults, each of whom was interviewed in a pre-election wave and then again in a postelection wave. The survey was conducted by YouGov using a “matched random sample methodology” to create a representative sample using nonprobability sampling methods (Reference Schaffner, Ansolabehere and LuksSchaffner et al., 2019). This methodology involves drawing a random sample from the broader population and then matching each individual from this “target sample” with one or more individuals from YouGov's existing pool of volunteer respondents. Thus, the resulting sample mirrors the random sample on a “large set of variables that are available in consumer and voter databases.” (Reference Schaffner, Ansolabehere and LuksSchaffner et al., 2019, p. 11).

The CCES' cooperative structure involves allocating subsets of respondents to groups of researchers' custom-designed questionnaires or “modules.” All 60,000 CCES respondents answered a common core of questions on the pre and postelection waves, and then were subdivided in groups of 1000 to participate in different researchers' modules. The sample size in our study is thus limited to 1000 respondents–those who participated in the module in which our questions of interest were placed.Footnote 11 Demographic data on this sample, as well as subsets relevant to our analysis, is available in the Appendix (Table A1).

Survey experiment

Our survey contributes to the growing use of experimentation to understand human rights issues by examining the conditions under which the American public approves or disapproves of overturning a successful application for asylum (see Reference BracicBracic, 2016; Reference Bracic and MurdieBracic & Murdie, 2020). The survey experiment presented respondents with a hypothetical applicant for refugee resettlement to the US from Afghanistan. This applicant met all of the legal requirements for refugee status, but then was revealed to have worked at a Taliban prison camp.

We chose a Taliban prison camp based on assumptions that suggest harsh judgments of refugee applicants who are affiliated with this group. First, though this survey was conducted prior to the extensive media coverage of the 2021 US withdrawal, we assume that most respondents have heard of the Taliban given the group's association with 9/11, as well as the longstanding war in Afghanistan and media coverage of it. There is little question that this organization has engaged in human rights violations both as insurgents and while in power in Afghanistan.Footnote 12 The Pakistan-based wing of the group is on the US terrorism watchlist, while the Afghan group is not.Footnote 13 However, for immigration purposes, the Taliban is considered a terrorist organization.Footnote 14 As a result, anyone affiliated with this group would fall into the wide net cast by “No Safe Haven” policies, and would not be allowed immigration benefits. Because the Taliban is widely known and reviled in the United States, we assume that respondents' openness to immigrants affiliated with this group, in particular, will be lower than with other insurgent or terrorist groups around the world. If respondents favor an applicant affiliated with the Taliban, they may be even more willing to support applicants affiliated with less well-known organizations.

The experimental manipulation varies the hypothetical applicant's role in the Taliban among three possible options: camp leader, prison guard, or dishwasher. These three roles represent distinct and decreasing levels of responsibility or culpability for Taliban human rights violations. Thus, the experiment allows us to test whether American' perceptions of deservingness change with these varying roles. Notably, however, all three roles meet the legal standard for the “material support” bar since all of them “promote, sustain, or maintain” a terrorist organization.Footnote 15 In other words, without a waiver that appears unlikely if not impossible to receive, none of these applicants would be granted immigration benefits.

The full text of the question is as follows, with experimentally varied text in bold:

“An Afghani applicant initially meets all of the criteria for a refugee visa. Upon further inspection, the applicant is found to have worked in a Taliban run-prison camp as a dishwasher/guard/camp leader. Do you agree or disagree that this applicant should be denied a visa?”

Respondents were randomly assigned to each of the three versions of the applicant's prison camp role. Because the assignment was truly random and thus independent in each case, the respondents were not divided perfectly evenly across conditions. In total, 351 respondents received the dishwasher, 318 received the guard treatment, and 331 received the leader treatment. Responses were collected on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strong agreement to strong disagreement.

Open-ended response

Immediately after answering the experimental question, respondents were asked an open-ended question as a follow-up or “retrospective probe” (Reference Zaller and FeldmanZaller & Feldman, 1992) into their thinking about their answer. The follow-up asked respondents to explain why they made their choice on the previous question: “In at least two sentences, please explain why you believe that this individual should or should not be denied a visa.” This approach enabled us to further explore how the public conceptualizes deservingness in each of the three experimentally-manipulated role conditions, rather than merely testing the effect of the role treatment on visa denial decisions.

Of the 1000 respondents who participated in the survey experiment, 704 (70.4%) gave an intelligible answer to this question (although many responses were shorter than the requested two sentences). Most of the remaining respondents did not write anything at all. A few wrote responses that could not be interpreted as expressing a reason for their prior answer, and so were not coded. The respondents were only slightly different politically and demographically from nonrespondents. In particular, open-ended respondents were more likely to be college-educated (39.8% were college-educated, compared to 36.2% in the full sample), and Democratic (49.5% either identified with or leaned toward the Democratic party, vs. 46.1% overall).Footnote 16

The open-ended responses were coded and analyzed with a grounded theory approach that draws from theoretically informed questions, data collection, and interpretation, comparing new data with concepts under development to elucidate emergent themes (Reference CharmazCharmaz, 2006; Reference Glaser and StraussGlaser & Strauss, 1967). Drawing from newer approaches that move away from a purely inductive approach to grounded theory research, our goal was to develop insights about the “situational fit between observed facts” and predictions about them (Reference Timmermans and TavoryTimmermans & Tavory, 2012, p. 171). While we were not working with explicit hypotheses about the contents of these responses, we did develop the questions with expectations that the experimental treatment would change people's reasoning as well as their decisions. For example, we were attuned to whether the international criminal law approach toward attributing blame on leaders but not followers might be reflected in the responses.

In our presentation of findings, we incorporate the open-ended responses into the analysis of the survey experiment, showing how reasons cited in the open-ended response varied across the three treatment groups, and how reasons cited correlated with decisions about the visa denial. This latter correlational analysis does not allow us to make causal claims, but it suggests the types of reasoning that are associated with the decision to grant or deny the visa within each of the three experimental conditions. With systematic analysis of the open-ended responses, we are able to provide distinct insights into how people think about deservingness in this morally fraught context.

Findings: Who deserves immigration benefits?

Our findings support the claim that, contrary to existing law and public policy, the American public takes into consideration the role a person played in a terrorist organization when determining whether they deserve immigration benefits. Furthermore, through analysis of open-ended responses, we find that role impacts reasoning as well, and that reasoning about deservingness clusters into two groups: either categorical or circumstantial assessments of the refugee applicants. In the latter group, respondents showed interest in why a person may have worked for the Taliban. These perspectives about deservingness and blameworthiness reflect concerns about the reasons behind a person's actions, and were associated with greater willingness to grant immigrant benefits.

Americans are more willing to admit a low-level worker

We begin with the main effects of the experiment on the visa decision. The results show that a substantively important share of the American public will make distinctions, even among those who have worked for an avowed enemy of the United States. Willingness to grant the visa was significantly greater, both statistically and substantively, when the applicant was a dishwasher as opposed to a guard or leader. The treatment shifted visa denial from a clear majority position in the guard and leader condition (supported by 68% and 70%, respectively) to a minority position in the dishwasher condition (40% support for denial). By our estimates, then, 30% of the American public supported visa denial for a Taliban leader but not for a dishwasher. In keeping with international criminal law logics focused on roles and responsibilities, respondents showed more willingness to deny immigration benefits to those in a position of greater responsibility within the Taliban. Moreover, in contrast to immigration policies that bar all applicants who provided even minimal material support to a terrorist organization, 60% of respondents were at least willing to consider granting the visa to the dishwasher, and approximately 30% did likewise even for the guard or leader.

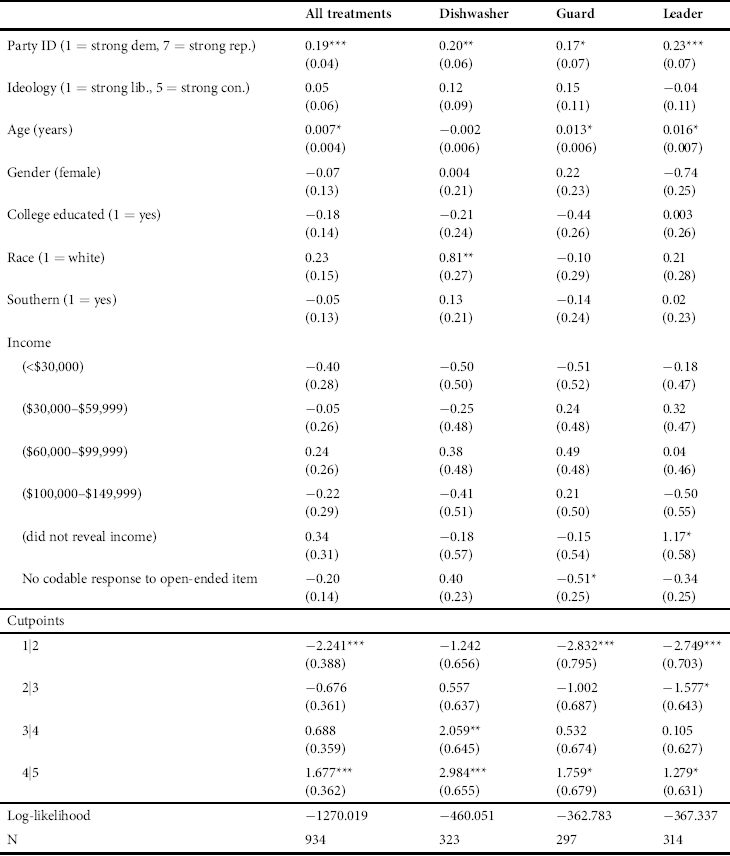

Table 1 shows the responses to the visa denial question in each of the three conditions, with the mean response below. In the dishwasher condition, the (weighted) mean response was near the center of the scale (mean = 3.31), neither agreeing nor disagreeing with the denial of the visa. In contrast, the mean response was in favor of denying the visa in both the guard (mean = 4.03) and leader (mean = 4.05) conditions. The difference between the dishwasher and each of the other two conditions was statistically significant at conventional levels, while the difference between the guard and leader condition was not. (A Kruskal Wallis test indicated differences across the conditions ![]() p < 0.001; pairwise post hoc Dunn tests indicated differences between dishwasher-guard (p < 0.001) and dishwasher-leader (p < 0.001), but not guard-leader (p = 0.36).)

p < 0.001; pairwise post hoc Dunn tests indicated differences between dishwasher-guard (p < 0.001) and dishwasher-leader (p < 0.001), but not guard-leader (p = 0.36).)

Table 1. Weighted mean and distribution of responses to visa denial question, by experimental treatment

Note: Cells are weighted proportions or weighted means with SE in parentheses.

Although this treatment effect is sizable, we should not overstate the generosity of the American public. Support for granting the visa remains a minority view even toward the dishwasher (26%), with 33% choosing the uncertain midpoint on the scale (“neither agree nor disagree”). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the guard and leader conditions. It seems that international criminal law logics about the responsibility of leaders as opposed to subordinates did not figure into decision-making at this level, or perhaps respondents saw no difference between guards' and leaders' level of responsibility.

While our focus is on the overall responses and the experimental effects, we also examined what types of people were more likely to support granting the visa by estimating ordinal logistic regression models of this decision, with political and demographic characteristics as independent variables. (Full results available in Appendix, Table A2.) Partisanship emerged as the main predictor, with Republicans more likely to deny the visa both in total and across each experimental condition. We also can observe the magnitude of partisan differences by simply taking the weighted proportion of Democratic and Republican respondents who are neutral or favorable toward granting the visa. Overall, 47% of Democrats and 23% of Republicans are neutral or favorable toward the visa; these proportions rise to 72% and 37%, respectively, in the dishwasher condition.

Other demographic variables had little or no independent estimated impact in a pooled model across all conditions, although older people were more likely to deny the visa. Further, unlike partisanship, demographic predictors were less consistent. For example, in the dishwasher condition, age drops out while race emerges as a significant predictor, with white people more likely to deny the visa than people of color were.

Categorical or circumstantial assessments

Next, we turn to the reasons people give for their decisions in the open-ended follow-up item. Even if they reflect motivated reasoning to explain the visa decision, these responses provide unique insights into how concepts related to moral blameworthiness map onto evaluations of deservingness in the immigration context. Our analysis reveals two distinct clusters of reasons. One cluster, which we label Circumstantial, displayed concern about the reasons why someone worked for the Taliban, while the other cluster, which we label Categorical, reflected evaluations of the Taliban itself without regard for individual circumstances.

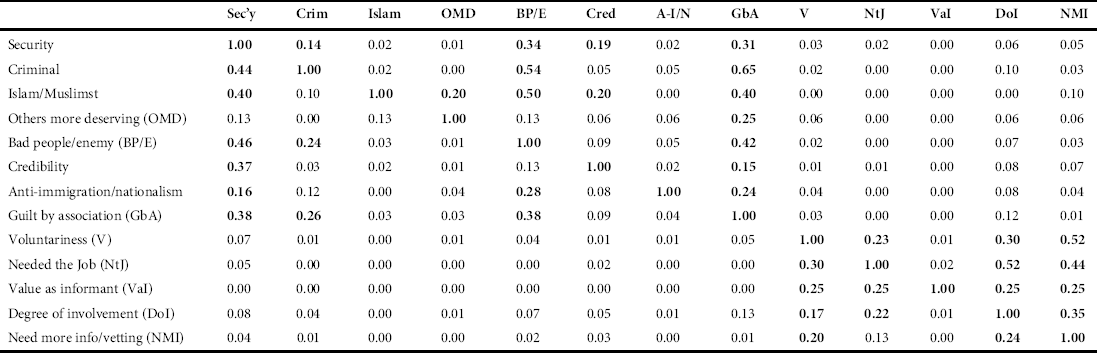

As noted, our coding strategy for this analysis was based in grounded theory, inductively generating codes and examining the situational fit with our theoretical framework about how notions of roles, responsibilities, motives, and actions might inform assessments of deservingness. The codes themselves as well as the relationships among them emerged from the respondents. Further, distinctions that initially seemed important were dissolved or eliminated if they did not reflect distinctions that commonly arose in respondents' language. Codes with fewer than four respondents were discarded from the analysis. Likewise, the final coding scheme merged Need More Information with Need Further Vetting because respondents did not draw the distinction we imagined between their own need to understand the individual case better and the perceived need for a more extensive vetting of potential refugees in US policy. Appendix Table A3 provides a listing of codes with the proportion of respondents in each, in descending order of frequency. The table also includes an example of a typical comment for each code.

Several codes, including some of the most common, seem to reflect negative categorical assessments of the visa applicant. Such responses characterized applicants as risks to US Security, as Criminal, or simply as Bad People or as Enemies of the US. These characterizations were often accompanied by language suggesting Guilt by Association, as applicants were considered unworthy of benefits because of their membership in the Taliban, regardless of their individual role or beliefs. These sorts of comments occurred in all three of the experimental conditions, as the following examples illustrate:

“Should be denied because he worked for the enemy” (guard condition).

“The Taliban is an avowed enemy of the US. Why should we admit our enemies?” (leader condition).

“Anyone associated with the Taliban should not be allowed here no matter what their position with the group” (dishwasher condition).

Another set of negatively-valenced responses occurred less frequently, but often enough to be noted. These responses invoked group-based attitudes based on religious or national identity, and were coded as references to Islam/Muslims, or as Anti-Immigration or Nationalist sentiment.

In contrast, another set of responses showed concern with individuals' circumstances or factors, rather than simply their membership in the Taliban or in broader identity categories. These responses, coded in categories such as Degree of Involvement, Voluntary/Involuntary, Needed to Work, Need More Information, mentioned both actions and intentions. These responses focused on whether the individual applicant was culpable for Taliban crimes, and whether they personally supported the Taliban's aims.

Individual open-ended responses often included more than one coded theme; these multifaceted responses provide information about which themes tend to go together within the same person's reasoning. To construct these relationships as a network, we identify co-occurrences within individual responses for every possible pair of codes. We then aggregate these co-occurrences, so that for every possible pair of codes, we know the proportion of responses in which those two codes appeared together. We created a network matrix (see Appendix, Table A3) of these proportions of co-occurrence. Finally, we represent the matrix of co-occurrences graphically in Figure 1, where connection between two codes means that the two concepts appeared together in the same responses. Specifically, for any pair of codes A and B, a tie from A to be means that at least 15% of responses that included code A also included code B. The thickness of the arrow increases as this percentage increases, and larger circles indicate more common responses.

FIGURE 1 Co-occurrences of themes within individuals' reasoning for visa decision. Nodes represent themes from open–ended responses (CCES 2018). F or any two nodes “A” and “B,” arrow from A to B indicates 15% or more of responses mentioning theme A also mention theme B. Size of circle is proportional to theme frequency; arrow thickness is proportional to frequency co-occurrence

Figure 1 shows the emergence of two clusters of codes that are fully distinct, and substantively meaningful. A small proportion of individuals' responses included a theme from both clusters, but no cross-cluster themes appeared frequently enough to qualify as a network tie under the criterion described above. The cluster that we label Circumstantial shows mutual links among concepts of voluntariness, levels of involvement, and possible need for work. Respondents invoking one of these concepts often invoked another, as well as wishing for more information about the particular case (Need More Information). Taken together, this cluster shows respondents taking some care to weigh the individual case before them. These respondents are asserting that, in order to make their decision to grant or deny a visa, they need to consider more than a mere association with the Taliban. They often say they want more information about what this person actually did and, more importantly, why they did it.

In contrast, the cluster we label Categorical shows that respondents who suggested that the refugee applicant was a bad person or part of an enemy organization also tended to invoke other notions of criminality, security risks, and guilt by association. This family of responses also included anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant or nationalist responses, although these responses were less frequent and less central to the cluster. Responses in this cluster reflect characterological or categorical assessments, in which participation in the Taliban or even broader categories of identity (as a Muslim and/or immigrant) are sufficient to deny immigration benefits.

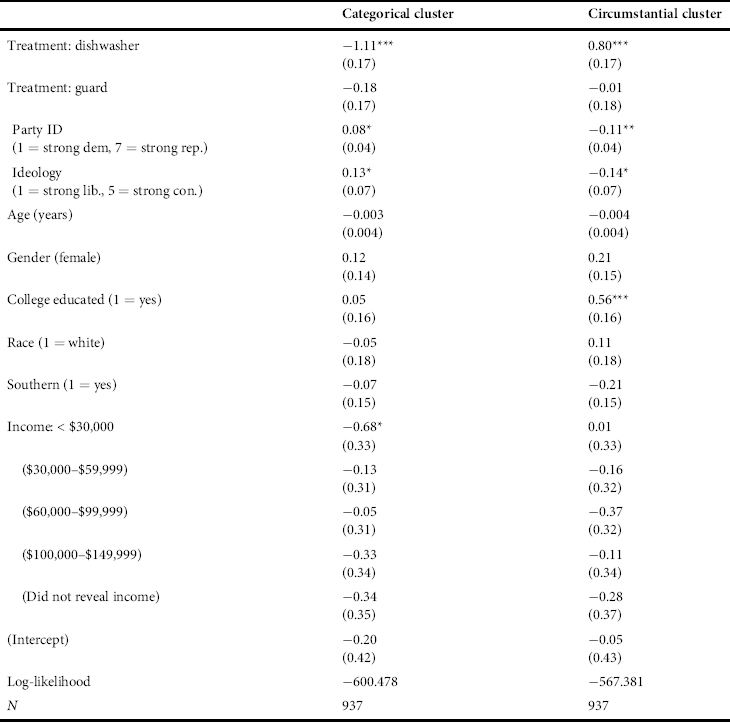

Across all three experimental treatments, the Categorical cluster included 41.6% of all respondents (and 58.8% of those who responded to the open-ended item), while the Circumstantial cluster included 34.0% of all respondents and 49.7% of those who responded to the open-ended item (all calculated with weighted proportions). To explore the correlates of cluster membership, we estimated logistic regression models predicting cluster membership based on demographic and political characteristics. As Table 2 shows, Democrats, self-reported liberals, and people with college degrees were more likely to give Circumstantial responses, while self-reported liberals and low-income earners were less likely to give Categorical responses. (See also Appendix, Table A1, A4, A5 for basic demographic data on each cluster.)

Table 2. Determinants of respondents' reasoning for visa denial

Note: Dependent variable in each model is binary variable indicating presence of a (categorical or circumstantial) theme in open-ended item responses. Cells contain estimated coefficients from logistic regression, with SE below in parentheses. Statistical significance indicated by asterisks (*** = p < 0.001; ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05). Reference categories as follows: “leader” for treatments, people of color for race (binary); $150,000 and up for income.

Circumstances matter less for leaders

Were these different sets of reasons linked to the experimental manipulation of roles and responsibilities? Further analysis suggests that they were: the experimental treatment affected not just the visa decision but also the types of rationales that respondents invoked to justify their decisions. Most simply, we can find that in the dishwasher condition, 26% of respondents had a categorical theme in their open-ended answer while 46% included a circumstantial theme. By contrast, in the guard and leader condition, the proportions were essentially reversed, with more categorical responses (49% guard, 53% leader) and fewer circumstantial (24% and 30%, respectively).

Further analysis confirms the statistically and substantively significant impact of experimental treatments on the respondents' reasoning. Referring back to Table 2, the logistic regression models include estimates of the impact of the dishwasher and guard treatment, relative to a baseline in the leader condition. The dishwasher treatment decreased the likelihood of a Categorical Cluster response and increased the likelihood of Circumstantial Cluster responses relative to this baseline, while the guard treatment had no statistically significant impact on responding in either cluster. Because these are logistic regression coefficients, we calculate the effect size by exponentiating our coefficients to convert from log-odds to odds ratios.Footnote 17 These calculations reveal that the dishwasher treatment reduced the odds of giving a Categorical Cluster response by 67% (odds ratio = 0.33), while more than doubling the odds of a Circumstantial Cluster response (odds ratio = 2.23). By comparison, a one-point shift on the Party Identification scale (i.e., from pure Independent to leaning Republican) was associated with an 8% increase in the odds of a Categorical response and an 11% decrease in the odds of a Circumstantial response.

To examine the relationship between treatments and specific response themes, we turn to Figure 2, which shows the proportion of respondents citing a given reason within each experimental condition. For example, the first panel of the Circumstantial Cluster section shows that close to 30% of respondents in the dishwasher treatment gave a response coded as Need More Information or Vetting, compared to less than 20% of those in the guard and leader conditions.Footnote 18

FIGURE 2 Taliban prison role experiment open–ended responses by treatment. Each panel shows proportion of full sample whose open–ended response included the given theme by treatment condition.

The dishwasher condition increased the frequency of responses from the Circumstantial Cluster. These include references to individual roles (Degree of Involvement) and also to motivation (Needed the Job), and to the ambiguity of the case (Need More Information). The guard and leader conditions, on the other hand, increased the proportion of several Categorical Cluster responses, particularly Security, Guilt by Association, and Credibility (particularly in the guard condition). Again, at the level of individual themes, categorical assessments were more common if the person being assessed had a role with more responsibility.

The lack of a relationship between the experimental treatments and the voluntariness code is surprising. We might have expected people to think more about voluntariness when asked about the dishwasher than the leader, for example. Leadership is presumably voluntary and even sought after, while a dishwasher might be envisioned as participating against their will. However, the oddity of this result dissolves when we examine the interaction between decisions and reasoning. As discussed in greater detail below, invoking voluntariness was associated with excusing the applicants' actions (and therefore favoring immigration benefits) in the dishwasher condition but not for the guard or leader.

We also note that across all three conditions, it was unusual to find explicit anti-immigrant, nationalist, or anti-Muslim rhetoric, which is surprising given the noted extent of stereotyping and negative categorical judgments of Muslim immigrants and Muslim-Americans (Reference LajevardiLajevardi, 2020; Reference Sides and GrossSides & Gross, 2013). Of course, these attitudes may underlie responses to both the closed-ended and open-ended question for some individuals without being explicitly mentioned.

Which circumstances matter? Respondents care about why a person worked for the Taliban

So far, we have made the case that applicants' role in the Taliban affected decisions about deservingness, and the reasons people give for those decisions. Next, we investigate the relationship between the visa decision and the reasons given. This analysis shows how different considerations, particularly concerns about motive or mental state, are linked to overall assessments of deservingness, although our data here do not allow us to make causal inferences. Figure 3 shows the distribution (mean and interquartile range) of responses to the visa denial question, within subgroups of respondents whose open-ended responses included each particular coded category. In this figure, categories are arranged in descending order beginning with the open-ended categories associated most strongly with denying the visa. Thus, the first panel shows that, among those who gave a response referring to Islam or Muslims, the mean response leaned strongly toward denying the visa, but with more variation in the dishwasher condition than the others.

FIGURE 3 Opinion on visa denial: differences by role experiment treatment. Panels show mean and distribution (interquartile range) of responses to closed—ended visa denial question, by treatment condition, for respondents whose open–ended response included the given theme.

As Figure 3 shows, people who gave Categorical responses were the most likely to have denied the visa. Beginning with Islam/Muslim and ending with Anti-Immigration/Nationalism, the response categories in this cluster are the ones with the highest average level of visa denial. Meanwhile, the codes from the Circumstantial Cluster show the most support for granting the visa, especially in the dishwasher condition. Responses focused on Degree of Involvement, Need More Information, and Voluntary/Involuntary were associated with granting the visa in the dishwasher condition more than in the guard or leader condition. In this cluster, only Needed to Work and the seldom-seen Value as Informant responses were associated with an equally favorable response toward the applicant in all three conditions. Finally, note that open-ended responses in the Circumstantial Cluster often were longer and more complex, receiving multiple codes. For example, the comment “Circumstances - forced labor? A member of the Taliban to survive? Careful vetting is necessary but my instinct would be to deny any member of the Taliban a visa” was coded with Voluntary/Involuntary, Needed to Work, and Need More Information.

We conclude the analysis by looking more closely at these circumstantial responses. Close reading of these responses reveals that evaluations of deservingness reflect concerns about intentions, particularly the motive for joining the group. First, a number of respondents open to granting the visa brought up the possibility of direct coercion. Relatedly, others suggested that the applicant might have had no other options, needing a way to support their family, for example. Among these respondents, such doubts often led to a desire for more information about the individual case, aimed at exploring the circumstances and determining whether the applicant had participated willingly and “enthusiastically.” As the following examples demonstrate, this focus on why the person participated emerged in all three experimental conditions (although in different frequencies, as seen above).

“Again depends. Forced to work as a guard or enthusiastically participated? No black and white answers because no black and white issues.” (guard)

“There needs to investigation on how they got there (into the job). Was it willingly or because of duress. What other options were available to then?” (dishwasher)

“I'm really not sure; things are often not this cut and dry. This person may have possibly worked at this camp in order to keep their family alive or some other unknown hypothetical reason. Does that lessen the seriousness of what they did?” (leader)

“Was it “just a job,” coerced employment? Deeper and diligent investigation is necessary. Sometimes people do things to survive in hopes to live long enough, protect their families, until an escape route opens up.” (guard)

Another answer along these lines provides additional clues into the reasoning, which has to do with whether or not the applicant believed in the organization's goals:

“Serving as a guard doesn't necessarily mean they hold the same beliefs. It may mean they were just trying to support their family in a difficult situation.” (guard)

All of these quotes illustrate concerns about judging people by their intentions as well as actions. They are not concerned about whether they worked with a terrorist organization, but why they did. As such, they illustrate that not only roles and responsibilities, but also acts as well as intentions, matter. Though our immigration laws and policies bar people who materially contributed to a terrorist organization regardless of the reason, and individuals in the US can be criminally prosecuted for doing so (18 U.S.C SS 2339A), these respondents suggest that being forced to work with a terrorist organization is not the same as doing so without coercion. Further, the quotes suggest that these respondents tried to distinguish what these applicants may have done from moral judgments about who they are, much as fact-finders in criminal cases are supposed to do.

These opinions reveal a more nuanced account of how criminal law logics mediate perspectives on deservingness of immigration benefits. These concerns go beyond international criminal law's focus on roles and responsibilities. For these respondents, what drives a person to do an action matters in the evaluation of whether and individual should or should not receive a refugee visa.

Conclusions: A more nuanced approach to no safe haven

Our findings illustrate that, unlike current policy, U.S. public opinion is open to an approach to immigration benefits that considers the actions and intentions of individuals affiliated with human rights abuses abroad, alongside their roles and responsibilities. These considerations, well developed in domestic and international criminal law, are largely absent from US immigration law. Rather, U.S. immigration law labels a wide range of organizations as terrorist groups, and any form of affiliation with them is a categorical bar to entry. Likewise, the law does not distinguish between two individuals who are members of the same terrorist organization but play strikingly different roles.

Despite this blanket legal hostility, our study suggests that a sizeable portion of the US public, albeit with some partisan differences, sees distinctions between roles, even in the most hostile and well-known organizations such as the Taliban. A majority of our representative sample did not choose to deny the visa of a low-ranking Taliban member, and these opinions included more than a third of Republicans in our sample. Though we did find differences among Republicans and Democrats, these opinions crossed party lines. Further, about a third of the sample—and about half of those who responded to the open-ended question—discussed their choice in ways that complicate simplistic, categorical understandings of blameworthiness. These findings have implications not only for immigration law and policy, but also sociolegal theory and empirical research on how individuals determine blameworthiness and deservingness, and on the convergence of immigration and criminal law regimes.

First, these findings complicate the growing literature on crimmigration by showing how criminal law logics mediate perspectives on restrictionist immigration policies, rather than simply reinforcing them. We find that beliefs about deservingness are closely related to interpretations of culpability, which reflect concerns about an applicant's actions and intentions behind those actions. Determining actions and intentions of immigrants peripherally associated with human rights violations is inherently challenging, and our data show that a majority of our respondents appreciate this difficulty in the case of a low-level Taliban member. A third of our respondents–and almost half of those who answered our follow-up probe–used reasoning associated with a reluctance to ascribe wholly negative categorical assessments to individuals who worked for the Taliban based. For a low-ranking Taliban member, this reluctance rose to almost half of all respondents, suggesting a role-dependent belief that motivations for joining the Taliban at that level may have more to do with coercive individual circumstances and less to do with beliefs or character.

The findings of this study underscore the complicated moral and ethical foundation of immigration law, which is by its very nature designed to place people into distinct categories even when their circumstances are complex. Although No Safe Haven policies reflect the convergence of criminal law and immigration law regimes, the underlying logics of domestic criminal law that say individuals' beliefs and intentions matter in assessments of criminal culpability. Such logics contradict efforts to generalize large swaths of immigrants associated with criminal acts, particularly those affiliated with a well-known organization engaged in human rights violations. Much as the field of criminology has called into question the stability of distinctions between “criminal” and “noncriminal,” those who attempt to migrate are frequently placed into binary categories such as legal/illegal or migrant/refugee that serve as a shorthand for moral distinctions between those who are deserving and undeserving of compassion (Reference HamlinHamlin, 2021; Reference TicktinTicktin, 2016). Our results support concerns that banning all who provide material support to terrorist organizations can overlook the varied ways they may provide support and reasons for doing so (Reference KarpKarp, 2009; Reference LeeLee, 2019).

Our findings thus provide additional insights into the well-documented convergence of immigration law and criminal law at the domestic level by adding an international dimension. Since scholars point to the salience of domestic crime in everyday politics and society and its effects on punitive attitudes, one might expect similar perspectives on individuals associated with international crime or terrorism. Certainly, previous studies have shown that negative perceptions of immigrants are often tied to rhetoric, rather than facts, about immigrant violence, particularly the racialized rhetoric of terrorist groups. However, our findings suggest that the American public does not universally judge individuals affiliated with terrorist groups as automatically undeserving of immigration benefits, in direct contrast to current laws and policies. The open-ended responses reveal some understanding of the challenges associated with surviving in an armed conflict, and varying levels of responsibility in human rights violations. These results map on to international criminal law approaches to culpability for mass violence, which are more focused on roles and responsibilities, and domestic criminal law logics that focus on actions and intentions.

We recognize that open-ended text responses on a survey are only one way to get at people's reasoning, and have limitations. In-depth interviews or focus groups with members of the public might enable us to get much richer and more nuanced understandings of people's thought processes and knowledge base. In addition, nonresponse to open-ended items may raise questions about the representativeness of those who do respond. Fortunately for the generalizability of our results, we find only minor partisan and demographic differences between respondents and nonrespondents on this item, as previously noted.

In summary, it is notable that a majority of a representative sample of Americans did not immediately decide to deny a visa to a low-ranking Taliban member, and that many of these respondents explicitly expressed a desire for contextual information to more fully assess the hypothetical applicant's degree of association with violence. These tendencies exist across partisan lines, although they are more common among Democrats. Even with these partisan differences, our results show that public opinion does not mimic the policy trend toward blanket restrictionism in US immigration politics. Instead, a significant portion seem to prefer careful analysis to assess whether potential immigrants should be assumed to share the values of the groups with which they were associated. Even in the hardest of cases–those who worked for an enemy of the state–much of the American public is capable of holding nuanced perspectives on what makes people deserving.

As Afghanistan falls back into Taliban control, and many Afghans are seeking refuge in wealthy liberal democracies, questions of deservingness and blameworthiness, of proximity to violence and affiliation with terrorist groups, have never been more relevant to immigration policy-making.Footnote 19 Our findings point to the need for a better-defined immigration policy that accounts for the variety of ways that people engage in violence during armed conflict. In addition to the dubious ways in which immigrants' method of border crossing and immigrants' behaviors after crossing have been criminalized, we expand this frame to argue that immigrants' behaviors before leaving their country of origin, particularly where there are human rights violations, are also complex and not easily categorized as victim or perpetrator.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Michael Kenwick for his thoughtful comments at the American Political Science Association Meeting, Meredith Loken and the Conflict, Violence, and Security Working Group at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and David Mednicoff and the Migration Working Group at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. We also want to thank Tatishe Nteta and the CCES team that helped facilitate the survey, Alphoncina Lyamula and Imtashal Tariq for their research assistance, Malcolm Blinder and Meredith Rolfe for their help with coding, and Christopher Klimmek for his incisive comments.

Funding information

University of Massachusetts Healy Endowment

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was generously supported by the University of Massachusetts Faculty Research/Healey Endowment grant.

APPENDIX

Table A1 Respondent characteristics, overall and by open-ended response type

Note: Cells contain unweighted proportions of sample or sample subset with a given characteristic, except for the first row, which contains mean age. Partisan categories include independents who lean toward a party. N for the last two columns sum to more than 704 because some respondents’ open-ended answer included a theme from both clusters.

Table A2 Demographic and political predictors of visa denial

Note: Cells contain coefficients estimated by ordinal logistic regression. Standard errors below in parentheses. Statistical significance indicated by asterisks (*** = p < 0.001; ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05).

Table A3 Co-appearances of response categories within individual response (data for Figure 1)

Note: Cells are proportions of respondents whose responses were coded in the row category that were also coded in the column category. Boldface indicates values (0.15 or greater) that were taken to indicate a link between categories.

Table A4 Open-ended response themes

Note: Numeric cells include weighted proportions of respondents giving open-ended response themes, within each experimental condition and overall (data for Figure 2). Cells in right-most column include prototypical examples of open-ended responses in the given response category. (Note that some open-ended responses were coded as containing more than one theme.)

Table A5 Mean response to visa denial question, by experimental treatment and open-ended response category (Data for Figure 3)

Note: Cells are means on a scale from 1 to 5, where higher values represent support for visa denial. Standard errors are below in parentheses. Categories are listed alphabetically.