Flavonoids in general and quercetin in particular have been associated with a decreased risk for CVD(Reference Erdman, Balentine and Arab1). Furthermore, there was a trend towards a reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus at higher quercetin intakes(Reference Knekt, Kumpulainen and Jarvinen2). In Western populations, the primary dietary sources of quercetin are tea, red wine, fruits and vegetables(Reference Linseisen, Radtke and Wolfram3, Reference Böhm, Boeing and Hempel4). Quercetin is one of the major flavonoids, ubiquitously distributed in (edible) plants, and one of the most potent antioxidants of plant origin(Reference Erdman, Balentine and Arab1). Numerous biological effects of quercetin, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic and vasodilatory actions, have been described in vitro (Reference Erdman, Balentine and Arab1). However, quercetin intervention trials in human subjects have so far shown inconclusive and even conflicting results(Reference Williamson and Manach5). Quercetin supplementation increased plasma antioxidant capacity, ex vivo resistance of LDL to oxidation and resistance of lymphocyte DNA to strand breakage, but decreased urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine concentrations(Reference Williamson and Manach5). Other human studies, however, failed to confirm effects on these biomarkers(Reference Williamson and Manach5). A recent meta-analysis of 133 controlled flavonoid trials(Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm6) suggested that there may be clinically relevant effects of some flavonoids or flavonoid-rich foods on CVD risk factors. Most of the trials, however, used flavonoid-rich products rather than isolated flavonoids. Thus, it remained unclear whether the observed effects could be attributed to the individual flavonoids. In addition, an optimal dose of specific flavonoids for cardiovascular protection could not be determined.

In respect of the CVD risk factors blood pressure, flow-mediated dilatation and blood lipids, the main focus of attention to date has been made on flavonoids from cocoa (for example, catechin, epicatechin) and soya(Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm6). Dark chocolate and cocoa appear to reduce flow-mediated dilatation acutely and reduce both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) after chronic intake(Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm6). Soya protein isolate significantly reduced DBP and LDL-cholesterol concentrations(Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm6–Reference Rimbach, Boesch-Saadatmandi and Frank8).

In a previous study, we had demonstrated that daily supplementation of normal-weight volunteers with 50, 100 or 150 mg quercetin dose-dependently increased plasma quercetin concentrations but did not significantly affect selected risk parameters for CVD in these healthy subjects(Reference Egert, Wolffram and Bosy-Westphal9), in whom a protective effect of quercetin was unlikely to occur. Thus, the aim of the present intervention study was to investigate the effects of quercetin supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors and biomarkers such as blood pressure, body composition, redox status, inflammation and blood lipids in overweight and obese subjects with a high-CVD risk phenotype. Another aim was to assess the safety of daily quercetin supplementation.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Participants were recruited from the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS) cohort(Reference Danielzik, Czerwinski-Mast and Langnase10) and the community of the city of Kiel, Germany, by notice-board postings, flyers and writing to families that are continuously followed up as a KOPS sub-cohort. From a total of 400 interested subjects, 172 subjects aged 25–65 years with a BMI 25–35 kg/m2 attended a screening which included physical assessments (height, body weight, blood pressure, pulse, waist and hip circumference), clinical assessments (liver function, serum lipids, glucose and uric acid, haematology, high-sensitivity (hs) C-reactive protein (CRP)), medical anamneses and dietary questionnaire.

Participants were included who had the following traits of the metabolic syndrome: (1) central obesity (waist circumference ≥ 94 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women); (2) serum concentration of TAG ≥ 1500 mg/l (1·7 mmol/l); and/or (3) serum concentration of hs-CRP ≥ 2·0 mg/l. Exclusion criteria were: smoking, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, liver, gastrointestinal or inflammatory diseases, a history of cardiovascular events, abnormal thyroid function, use of anti-obesity medications, dietary supplements, anti-inflammatory drugs, cancer, recent major surgery or illness, pregnancy or breast-feeding, alcohol abuse, participation in a weight-loss programme, necessity for a medically supervised diet or >5 kg weight loss within the 3 months before the study.

Ninety-six subjects (forty-two male, fifty-four female) were included into the study. Two subjects dropped out because they found the study protocol too demanding and one subject was excluded due to gastrointestinal symptoms. Only data from those ninety-three participants (forty-two male, fifty-one female) who completed the entire intervention study were included in the analysis and are subsequently reported.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of the Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Advice was given to the subjects to maintain their habitual diet, physical activity levels, lifestyle factors, and to maintain a stable body weight. Participants taking oral contraceptives (n 14; 27·5 % of women), or antihypertensive (n 15; 16·1 %) or lipid-lowering drugs (n 3; 4·3 %), were instructed to continue taking their medications.

Study design

The study was undertaken as a double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over trial with 6-week (42 d) treatment periods separated by a 5-week washout period. Subjects were instructed to take a total of six capsules per d, two capsules with each principal meal. Capsules were distributed with a surplus of 10 %. The hard gelatine capsules contained quercetin dihydrate (Voigt Global Distribution Inc., Lawrence, KS, USA), mannitol and the flow-regulating excipient silicium dioxide. The capsules were produced at the Institute of Pharmacy, Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany (Dr Peter Langguth). A quercetin dosage of 150 mg/d was selected to represent the 15-fold of the estimated daily quercetin intake in Germany of about 10 mg(Reference Linseisen, Radtke and Wolfram3, Reference Böhm, Boeing and Hempel4). Bioavailability of this quercetin dosage was examined in our previous study(Reference Egert, Wolffram and Bosy-Westphal9).

Subjects were assigned to placebo or quercetin groups by blocked randomisation procedure, separately for men and women. Capsules (quercetin or placebo) were handed out at days 0 and 21 of each treatment period and leftovers were collected at days 21 and 42. Compliance was monitored by determining quercetin plasma concentrations (see below), by capsule count at the end of the study and by instructing subjects to document capsule consumption, observed side-effects, deviations from their normal physical activity, or any other observations considered relevant in a study diary.

Subjects were instructed to keep 3 d food records at baseline and end of the treatment arms of the study. Each record represented the food intake of 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day. These dietary records were used to calculate the habitual dietary energy and nutrient intake.

Sample size was calculated based on expected changes in TNF-α. The power calculation revealed that ninety-four subjects had to complete the study to reach a 99 % power to detect a 0·5 pg/ml difference in TNF-α concentrations between the placebo and quercetin groups at P < 0·001(Reference Scales and Rubenfeld11).

Anthropometry, body composition, resting blood pressure and pulse rate

Body height was determined on a stadiometer to the nearest 0·5 cm during the first examination. All other parameters listed below were measured on days 0, 21 and 42 of each intervention period. On these days, participants were asked to visit the study unit in the early morning after an overnight fast.

For waist and hip measurements, participants were asked to roll down their undergarments. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0·5 cm midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest, while the subject was at minimal respiration. Hip circumference was measured at the height of the greater trochanters. Both measurements were performed in duplicate in an upright position.

Body composition (fat mass and fat-free mass) was determined by air-displacement plethysmography using the BOD POD Body Composition System (Life Measurements Instruments, Concord, CA, USA), which is composed of a plethysmograph, an electronic scale and a personal computer (BOD POD software, version 2.14). A detailed description of the measurement is given elsewhere(Reference Bosy-Westphal, Danielzik and Becker12). Body weight was determined to the nearest gram. Overweight (BMI ≥ 25–29·99 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2) were classified according to the WHO's criteria for adults(13).

Blood pressure measurements were obtained with a standard manual sphygmomanometer under standardised conditions according to the recommendations of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research(Reference Pickering, Hall and Appel14). Each participant sat quietly for 5–10 min, after which their arm was placed at heart level, and SBP and DBP were measured at least twice in 3–5 min intervals. If blood pressure measurements varied by ≥ 10 mmHg, an additional measurement was performed. The accumulated measurements were then averaged to determine overall SBP and DBP. Pulse pressure (or blood pressure amplitude) was calculated as the pressure difference between SBP and DBP. Resting pulse rate was measured by hand palpation at the radial artery. All measurements were performed by the same trained investigator.

Blood sampling

Fasting venous blood samples were taken at the first and last day of the treatment arms. All samples were taken between 07.00 and 08.30 hours after an overnight fast under standardised conditions. The subjects abstained 24 h from alcohol and were told not to engage in strenuous exercise on the day before blood sampling. The last two capsules were taken about 12 h before blood sampling. Blood was drawn into tubes containing EDTA, lithium heparin, or no additives (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Plasma and serum were obtained by centrifugation at 2000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Samples of plasma and serum were immediately frozen and stored in gas-tight cryovials at − 75°C until analysis. Clinical safety and haematological parameters (see below) were assayed from fresh samples within 3 h after venepuncture. All laboratory measurements were performed without knowledge of the treatment.

Clinical safety parameters and haematological measurements

Serum alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, cholesteryl esterase as well as serum concentrations of creatinine, K and Na were determined using enzymic methods with a Konelab 20i analyser (Kone, Espoo, Finland). Haematological parameters (leucocyte count, erythrocyte count, platelet count, Hb concentration, packed cell volume, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular haemoglobin and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration) were determined by using a CELL-DYN 3700 autoanalyser (Abbott Diagnostics Europe, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Serum lipid parameters, glucose and uric acid

Serum concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and TAG as well as glucose and uric acid were measured using the Konelab 20i analyser (Kone) with the manufacturer's assay kits, quality controls and reagents.

Plasma high-sensitivity TNF-α

Plasma concentrations of TNF-α were determined with the use of a high-sensitive ELISA (R&D Systems, Europe Ltd, Abingdon, Oxon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The limit of detection was 0·106 pg/ml (information supplied by the manufacturer of the kit).

Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Serum concentrations of CRP were measured using an automated high-sensitivity IMMULITE two-site chemiluminescent enzyme immunometric assay (Immulite System; Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA, USA). The limit of detection was 0·1 mg/l.

Plasma oxidised low-density lipoprotein

Circulating oxidised LDL was determined using a commercial ELISA kit (Immundiagonstik AG, Bensheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The limit of detection was 4·13 ng/ml.

Antioxidant capacity of plasma

The antioxidant capacity of plasma was determined with the oxygen radical absorbance capacity in a ninety-six-well plate according to a modified method of Cao et al. (Reference Cao, Alessio and Cutler15). 2,2′-Azobis(2-amidinopropan) was used to generate peroxyl radicals, trolox served as the control and sodium fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. In brief, 25 μl of blank, trolox standard or acetone-precipitated plasma sample were mixed with 250 μl sodium flourescein and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Subsequently, 25 μl 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropan) solution were added and fluorescence was detected at excitation wavelength 485 nm and emission wavelength 520 nm every 1 min for 50 min. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity values were calculated by the area under the curve.

Plasma flavonoids

Analyses of plasma concentrations of quercetin, its monomethylated derivative isorhamnetin (3′-O-methyl quercetin) and of kaempferol were performed by HPLC with fluorescence detection as described previously(Reference Bieger, Cermak and Blank16). All samples were treated enzymically with β-glucuronidase/sulfatase type H-2 (crude enzyme extract from Helix pomatia; Sigma-Aldrich AG, Taufkirchen, Germany) before the extraction of the flavonols. Authentic flavonols (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) were used as external standards.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package (version 15; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Distribution of data was analysed by checking histograms and normal plots of the data, and normality was tested by means of Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Baseline characteristics of the groups were compared by means of independent-sample t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests. Comparison of normally distributed data between groups was performed using the unpaired Student's t test and within a group using the paired Student's t test. Data that were not normally distributed were compared using the Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. Relationships between variables were evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficient. In all cases, a value for P ≤ 0·05 (two-sided) was taken to indicate a significant effect. Unless otherwise indicated, results are expressed as mean values and standard deviations. A test for carry-over effects according to Kenward & Jones(Reference Kenward and Jones17) was used. No carry-over effects between the two treatment periods could be observed.

Results

Baseline characteristics, compliance and dietary intake

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects at screening are presented in Table 1 for the group as a whole and for men and women separately. Due to selection criteria all subjects were overweight (45·2 %) or obese (54·8 %). We observed sex differences with respect to body height, body weight, waist circumference, waist:hip ratio, fasting serum concentrations of hs-CRP, HDL-cholesterol, TAG and uric acid (Table 1).

Table 1 Subject characteristics and blood parameters at screening

(Mean values and standard deviations)

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

*** Mean value was significantly different from that of women (P < 0·001; Mann–Whitney U test).

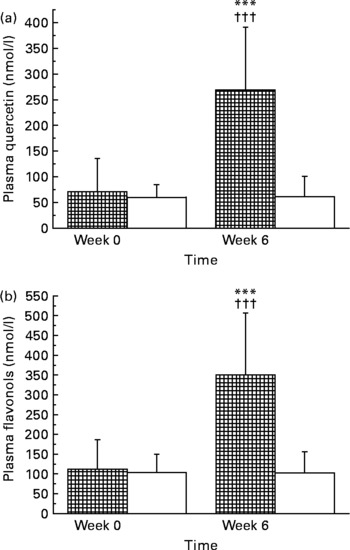

Compliance with treatment, determined by counting the returned capsules and evaluation of the daily records, was high: 97·9 and 98·1 % during quercetin and placebo consumption, respectively, and was not significantly different between the treatment groups and periods. Quercetin plasma concentrations were similar in both treatment groups at baseline and compliance with quercetin supplementation was confirmed by a marked increase in plasma quercetin concentrations by 349 % (P < 0·001) in subjects taking quercetin, but not placebo capsules (Fig. 1). We observed high inter-individual variation in plasma quercetin concentrations before (the range for all study subjects was 28·6–466·7 nmol/l) and after supplementation (placebo group range: 18·6–334·3 nmol/l; quercetin group range: 43·2–740·9 nmol/l). The 5-week washout period was sufficient to reduce plasma quercetin back to baseline values (data not shown). No significant sex differences in quercetin concentrations at baseline or after quercetin supplementation were observed.

Fig. 1 Plasma concentrations of quercetin (a) and total flavonols (b) in human subjects before and after 6-week supplementation with quercetin (150 mg/d; ![]() ) or placebo (□). Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. *** Mean value was significantly different from that at baseline (P < 0·001; intra-group comparison; Wilcoxon test). ††† Change during quercetin treatment was significantly different from that during placebo treatment (P < 0·001; inter-group comparison; Mann–Whitney U test). The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to quercetin or flavonol concentrations at baseline (Mann–Whitney U test). Total plasma flavonols were calculated according to: total flavonols (nmol/l) = quercetin (nmol/l) plus kaempferol (nmol/l) plus isorhamnetin (nmol/l). Note that the y axes show different concentration ranges.

) or placebo (□). Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. *** Mean value was significantly different from that at baseline (P < 0·001; intra-group comparison; Wilcoxon test). ††† Change during quercetin treatment was significantly different from that during placebo treatment (P < 0·001; inter-group comparison; Mann–Whitney U test). The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to quercetin or flavonol concentrations at baseline (Mann–Whitney U test). Total plasma flavonols were calculated according to: total flavonols (nmol/l) = quercetin (nmol/l) plus kaempferol (nmol/l) plus isorhamnetin (nmol/l). Note that the y axes show different concentration ranges.

Three-day dietary records were analysed in a randomised sample of fifty-two subjects and no significant differences between groups and within groups (comparing beginning and end of the treatment periods) in mean daily intakes of energy (10·0 MJ/d), protein (15·4 % energy intake), carbohydrates (43·4 % energy intake), fat (37·8 % energy intake), fatty acids, cholesterol, antioxidants (vitamin E, 1·3 mg/MJ; vitamin C, 11·8 mg/MJ) or dietary fibre (2·4 g/MJ) were observed.

Safety parameters

Biomarkers of liver and kidney function (alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, cholesteryl esterase, creatinine), haematology and serum electrolytes were all within normal ranges at all times and no differences were observed between the groups (data not shown).

Body weight, waist circumference and body composition

Quercetin supplementation did not significantly affect body weight, waist circumference, fat mass or fat-free mass (data not shown). However, in women, there was a small decrease in fat mass ( − 0·57 (sd 1·58) kg; P < 0·05) and an increase in fat-free mass (0·52 (sd 1·26) kg; P < 0·01) in the placebo group, but no between-group differences in changes of body composition were observed (data not shown).

Resting blood pressure, pulse rate, serum lipids, glucose and uric acid

In contrast to placebo, quercetin supplementation significantly decreased SBP by 2·6 (sd 9·1) mmHg (P < 0·01) in the entire study group, by 2·9 (sd 9·5) mmHg (P < 0·01) in the subgroup of (pre-)hypertensive subjects (defined as SBP ≥ 120 or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg(Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black18)) and by 3·7 (sd 7·4) mmHg (P < 0·001) in the subgroup of younger adults aged 25–50 years (Table 2). In the latter subgroup, the decrease from baseline was significantly different from the placebo group (P < 0·05) (Table 2).

Table 2 Resting systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse pressure and pulse rate in human subjects before and after 6-week supplementation with quercetin (150 mg/d) or placebo‡

(Mean values and standard deviations)

Mean value was significantly different from that at baseline: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001 (intra-group comparison; Wilcoxon test).

† Change during quercetin treatment was significantly different from that during placebo treatment (P < 0·05; Mann–Whitney U test).

‡ The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to blood pressure parameters and pulse rates at baseline (Mann–Whitney U test).

§ SBP < 120 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg.

∥ SBP ≥ 120 mmHg or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg.

Quercetin treatment significantly decreased pulse pressure in the total study group, in (pre-)hypertensive subjects and in the subgroup of younger adults (Table 2). Resting pulse rate did not significantly change during quercetin treatment (Table 2).

Quercetin supplementation did not significantly affect serum concentrations of total cholesterol, TAG, glucose or uric acid (Table 3). Serum concentrations of LDL-cholesterol were significantly decreased by both quercetin and placebo treatment, but were not significantly different between groups (Table 3). Compared with placebo, quercetin significantly decreased HDL-cholesterol concentrations (Table 3). The LDL:HDL-cholesterol and TAG:HDL-cholesterol ratios were not significantly changed by quercetin or placebo treatment (Table 3).

Table 3 Fasting serum lipids and lipoproteins, serum glucose and serum uric acid in human subjects before and after 6-week supplementation with quercetin (150 mg/d) or placebo‡

(Mean values and standard deviations)

Mean value was significantly different from that at baseline: * P < 0·05, *** P < 0·001 (intra-group comparison; Wilcoxon test or paired t test).

††† Change during quercetin treatment was significantly different from that during placebo treatment (P < 0·001; Mann–Whitney U test or t test).

‡ The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to any of the variables at baseline (independent-sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test).

High-sensitivity TNF-α, high-sensitivity C-reactive-protein, oxidised LDL and plasma antioxidant capacity

Quercetin and placebo treatment significantly decreased serum concentrations of hs-TNF-α from baseline by 0·25 (sd 0·73) pg/ml (P < 0·001) and by 0·08 (sd 0·87) pg/ml (P < 0·05), respectively. Changes from baseline were not significantly different between groups (Table 4). Neither quercetin nor placebo significantly altered serum concentrations of hs-CRP, as analysed for the total study group (Table 4) and separately for men and women (data not shown). However, in subjects with baseline hs-CRP concentrations ≥ 2 mg/l, quercetin as well as placebo treatment significantly decreased hs-CRP by 2·35 (sd 11·20) mg/l (P < 0·01) and by 1·35 (sd 3·49) mg/l (P < 0·01), respectively. These changes did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Table 4 Serum high-sensitivity TNF-α (hs-TNF-α), serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), plasma oxidised LDL and plasma antioxidant capacity (ORAC) in human subjects before and after 6-week supplementation with quercetin (150 mg/d) or placebo‡

(Mean values and standard deviations)

Mean value was significantly different from that at baseline: * P < 0·05, *** P < 0·001 (intra-group comparison; Wilcoxon test).

† Change during quercetin treatment was significantly different from that during placebo treatment (P < 0·05; Mann–Whitney U test).

‡ The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to any of the variables at baseline (Mann–Whitney U test).

Quercetin supplementation decreased serum concentrations of oxidised LDL by 170·8 (sd 328·5) ng/ml (P < 0·001). This change was significantly different (P < 0·05) from the decrease by 88·8 (sd 360·3) ng/ml (P < 0·05) during placebo treatment (Table 4). No significant associations were found between circulating oxidised LDL concentrations and serum LDL-cholesterol or between oxidised LDL concentrations and biomarkers of inflammation (data not shown). The plasma oxygen radical absorbance capacity was not significantly affected by quercetin or placebo treatment (Table 4).

Correlations of blood pressure parameters, oxidised LDL, high-sensitivity TNF-α and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with plasma quercetin concentrations

SBP, pulse pressure, plasma oxidised LDL concentrations, serum hs-TNF-α and serum hs-CRP concentrations were not significantly correlated with plasma concentrations of quercetin (data not shown).

Discussion

The aim of the present double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over intervention study was to investigate the effect of a 6-week supplementation with quercetin (150 mg/d) on individuals with a high-cardiometabolic risk phenotype on established CVD risk biomarkers. Our major finding was that quercetin supplementation significantly reduced SBP. This effect was most pronounced in subjects aged 25–50 years. In addition, quercetin caused a significant reduction in plasma concentrations of atherogenic oxidised LDL. In contrast, there were no effects of quercetin on biomarkers of inflammation and metabolism including body composition. We used a moderate supranutritional but non-pharmacological dose of quercetin, since these data should provide a rational basis for the development of functional foods.

Blood pressure

To the best of our knowledge, so far only two human studies have examined the effect of quercetin supplementation on arterial blood pressure(Reference Conquer, Maiani and Azzini19, Reference Edwards, Lyon and Litwin20). Conquer et al. (Reference Conquer, Maiani and Azzini19) reported no changes in SBP or DBP when healthy volunteers (mean age 42 years) with mean baseline blood pressure of 122/79 mmHg and a mean BMI of 26 kg/m2 were supplemented with a high (non-nutritional) dosage of 1000 mg quercetin/d for 8 weeks. In contrast, Edwards et al. (Reference Edwards, Lyon and Litwin20) recently found that 4-week supplementation with 730 mg quercetin/d significantly reduced SBP ( − 7 mmHg) and DBP ( − 5 mmHg) in subjects with stage 1 hypertension but not in those with prehypertension. However, a non-significant reduction in blood pressure was also observed in the placebo group and the authors did not report significant differences between the quercetin and placebo groups. It was concluded that a certain degree of hypertension might be required for quercetin to exert a blood pressure-lowering effect.

Our data further indicate that age is an important factor for blood pressure-lowering effects of quercetin. We hypothesise that improved endothelial function might be the underlying mechanism that may act especially in younger and middle-aged individuals. In this group higher blood pressures are mainly caused by an increase in peripheral vascular resistance generated by functional and structural narrowing of the resistance arteries and arterioles. As age advances, structural damage and disease in larger conduit arteries become more important determinants of blood pressure. As atherosclerotic modifications of the vasculature, resulting in arterial stiffening and loss of vascular function, aggravate with age(Reference Williams, Lindholm and Sever21), the potential to improve vascular function by nutrients declines.

Because endothelial dysfunction is critical in atherosclerosis and hypertension(Reference Landmesser, Hornig and Drexler22), improving endothelium-dependent vasodilation is one possible mechanism by which flavonoids may reduce cardiovascular risk(Reference Hooper, Kroon and Rimm6). The results of a recent placebo-controlled intervention study in healthy subjects (mean blood pressure of 123/78 mmHg) suggested that pure quercetin can improve endothelial function by modulating the circulating concentrations of vasoactive NO products and endothelin-1(Reference Loke, Hodgson and Proudfoot23). These effects may be explained by inhibition of NADPH oxidase and the activation of endothelial NO synthase. In fact, acute treatment with 200 mg quercetin increased endogenous NO (S-nitrosothiols, nitrite and nitrate) but reduced endothelin-1 production(Reference Loke, Hodgson and Proudfoot23).

In vitro studies about the vascular effects of quercetin showed that it may exert multiple actions on the NO-guanylyl cyclase pathway, endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor(s) and endothelin-1 and protect endothelial cells against apoptosis(Reference Perez-Vizcaino, Duarte and Andriantsitohaina24). In vivo, quercetin prevented endothelial dysfunction and reduced blood pressure, oxidative stress and end-organ damage in hypertensive animals(Reference Perez-Vizcaino, Duarte and Andriantsitohaina24). Quercetin may exert its effect on endothelial function specifically when endothelial function is impaired and blood pressure is elevated.

Lifestyle modification has been emphasised in prehypertensive and hypertensive individuals as an initial intervention to control blood pressure(Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black18). The quercetin-induced reduction of blood pressure in our subjects was similar to the effects of Na reduction, increased physical activity, alcohol reduction(Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black18) or fish oil supplementation(Reference Morris, Sacks and Rosner25).

A potential limitation in the interpretation of our quercetin effects on SBP is the fact that we only measured the office blood pressure in the resting state. Future studies should integrate 24 h ambulatory blood pressure measurements with a total number of readings between 50 and 100 to reveal valid additional data about the effects of quercetin on mean 24 h, daytime and night-time ambulatory blood pressure. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring will therefore give a better description about the effects of daily quercetin supplementation than one-off office measurements.

Atherogenic oxidised LDL

Quercetin protects against free radical damage via scavenging activity in vitro (Reference Erdman, Balentine and Arab1). In the light of a relatively low bioavailability and an intensive metabolic transformation of orally applied quercetin, however, a direct role of plasma quercetin as an in vivo antioxidant has been questioned(Reference Lotito and Frei26). Nevertheless, the present results showed that quercetin significantly reduced plasma concentrations of oxidised LDL. Conversion of LDL to oxidised LDL is considered to be a key event in atherogenesis(Reference Stocker and Keaney27). Concentrations of oxidised LDL are increased in patients with the metabolic syndrome(Reference Holvoet, Kritchevsky and Tracy28) and are associated with obesity, dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance(Reference Holvoet29). Increased oxidised LDL was predictive for future myocardial infarction(Reference Holvoet, Kritchevsky and Tracy28, Reference Holvoet29). Our finding is in line with Ruel et al. (Reference Ruel, Pomerleau and Couture30) who showed that flavonoid-rich cranberry juice containing quercetin significantly decreased oxidised LDL concentrations in overweight subjects. In a recent cell-culture study quercetin and some of its major in vivo metabolites (for example, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide) inhibited neutrophil-mediated LDL oxidation at physiological concentrations(Reference Loke, Proudfoot and McKinley31). The presence of quercetin glucuronides in human atherosclerotic lesions further suggests that quercetin may be available to prevent LDL oxidation in vivo (Reference Kawai, Nishikawa and Shiba32). These results together with data from the present study support that quercetin may act as an antioxidant in vivo.

Inflammation

Quercetin has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects. Nair et al. (Reference Nair, Mahajan and Reynolds33) showed that quercetin dose-dependently inhibited the gene expression and production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This effect was explained by modulation of the NF-κB signal transduction cascade. In obese Zucker rats, a high dose of quercetin (10 mg/kg body weight) improved the inflammatory status, as it decreased the production of TNF-α by the visceral adipose tissue, and increased the plasma concentrations of the anti-inflammatory adipocytokine adiponectin(Reference Rivera, Moron and Sanchez34). Since obese and type 2 diabetes Zucker rats and obese humans are characterised by adipose tissue overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and by decreased plasma concentrations of anti-inflammatory adipocytokines such as adiponectin(Reference Hotamisligil, Arner and Caro35–Reference Galisteo, Sanchez and Vera37), it is tempting to speculate that quercetin may affect serum levels of inflammatory cytokines.

In the present human study, quercetin had no anti-inflammatory effect in overweight or obese subjects with a high-CVD risk phenotype. Although we found a significant decrease of serum hs-TNF-α during quercetin supplementation and also a significant decrease in hs-CRP in subjects with elevated baseline hs-CRP concentrations ( ≥ 20 mg/l), both changes did not differ significantly between quercetin and placebo. These results are in line with the results in healthy normal-weight volunteers(Reference Egert, Wolffram and Bosy-Westphal9, Reference Boots, Wilms and Swennen38), where the lack of effect was probably due to the low cytokine and high antioxidant level at baseline, indicating that neither inflammation nor oxidative stress was present.

As the experimental studies including our previous findings in mice(Reference Boesch-Saadatmandi, Wolffram and Minihane39) showed anti-inflammatory effects at high plasma quercetin concentrations (>1 μm)(Reference Nair, Mahajan and Reynolds33, Reference Boots, Wilms and Swennen38) or at a high supranutritional quercetin dosage (for example, 10 mg/kg body weight in obese rats)(Reference Rivera, Moron and Sanchez34), we speculate that a quercetin dosage of 150 mg/d (1·6 mg/kg body weight) and the plasma quercetin concentrations of about 0·3 μm reached were too low to induce a significant anti-inflammatory effect.

Metabolism

Some flavonoids, particularly green-tea catechins such as epigallocatechin gallate, may affect energy metabolism. For example, in healthy normal-weight human subjects, consumption of green tea extracts has been shown to increase fatty acid oxidation and energy expenditure, particularly if combined with a metabolic stimulant such as caffeine(Reference Berube-Parent, Pelletier and Dore40–Reference Venables, Hulston and Cox42) and to reduce total and abdominal fat in subjects with visceral fat-type obesity(Reference Nagao, Komine and Soga43). However, in accordance with our previous study in healthy normal-weight subjects(Reference Egert, Wolffram and Bosy-Westphal9), we found no significant effects of quercetin on fat mass.

Quercetin has also been shown to have hypocholesterolaemic and hypotriacylglycerolaemic effects in animal studies(Reference Igarashi and Ohmuma44, Reference Yugarani, Tan and Teh45), but respective human studies conducted so far using quercetin supplements could not support these effects(Reference Egert, Wolffram and Bosy-Westphal9, Reference Conquer, Maiani and Azzini19, Reference Edwards, Lyon and Litwin20). However, there are two human studies that showed an improvement in lipoprotein profiles during supplementation with concentrated red grape juice(Reference Castilla, Echarri and Davalos46) and lyophilised grape powder(Reference Zern, Wood and Greene47), both rich in quercetin. In the present study, we found a small, but significant decrease in HDL-cholesterol during quercetin treatment. The decrease in HDL-cholesterol concentration, however, was not associated with an increase in the LDL:HDL-cholesterol or TAG:HDL-cholesterol ratios, respectively. Thus, we conclude, that the small decrease in HDL-cholesterol concentration during the quercetin supplementation might be of only limited, if any, physiological or clinical relevance.

The precise underlying molecular mechanism that may be responsible for the HDL-cholesterol-modulating effect by quercetin has not been elucidated up to now. Castilla et al. (Reference Castilla, Echarri and Davalos46) found that the increase in HDL-cholesterol concentration during flavonoid-rich grape juice consumption was paralleled by an increase in apo A1 concentrations. This indicates that flavonoids may affect hepatic apo A1 secretion in vivo, as described in a cell-culture study using HepG2 hepatocytes(Reference Theriault, Wang and Van Iderstine48).

Safety parameters

As with any intervention, potential risk also must be considered. Our data suggest that the daily supplementation of 150 mg quercetin aglycone by volunteers with a high-CVD risk phenotype for the duration of 6 weeks is safe.

In conclusion, the present study showed that dietary supplementation of the diet with 150 mg quercetin/d significantly reduced SBP and plasma oxidised LDL concentrations in overweight subjects with a high-CVD risk phenotype. Our findings provide further evidence that quercetin may provide protection against CVD. Further studies are needed to confirm the physiological and clinical relevance of these results.

Acknowledgements

We thank Petra Schulz and Angelika Thoss for excellent technical assistance.

The project was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 0313856A) within the project ‘Functional Foods for Vascular Health – from Nutraceuticals to Personalised Diets’. None of the authors has any personal or financial conflicts of interest in the publication of this paper.

M. J. M. and G. R. provided funding. S. E. and M. J. M. designed the study. S. E., A. B.-W., J. S., C. K. and U. S. recruited the subjects and performed the study. S. P.-D. performed the blinding procedure. J. F. produced the capsules. S. E., J. S., C. K., U. S., A. E. W., J. S. and S. W. participated in data collection and analysis. S. E. performed the statistical calculations. S. E. and M. J. M. wrote the manuscript. G. R., S. W. and J. F. contributed to the final discussion of the results. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.