Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a debilitating and disabling mental illness that is complicated by its psychiatric comorbidities (e.g. major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder and generalised anxiety disorder) and significant functional impairment.Reference Brakoulias, Starcevic, Belloch, Brown, Ferrao and Fontenelle1 Clinical guidelines recommend cognitive–behavioural therapy, exposure and response prevention and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as first-line treatments for OCD.Reference Koran, Hanna, Hollander, Nestadt and Simpson2,Reference Pallanti, Hollander, Bienstock, Koran, Leckman and Marazziti3 However, symptom improvement from these treatments may take weeks to months, and up to 40–60% of patients are treatment-resistant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.Reference Koran, Hanna, Hollander, Nestadt and Simpson2,Reference Pallanti, Hollander, Bienstock, Koran, Leckman and Marazziti3 Given the existing limitations of first-line treatments for OCD, a primary preventative approach that targets the modifiable risk factors of mental illness must also be considered.

Mechanisms implicated in diet and OCD

Advances in developing novel therapies for OCD have been limited by an imprecise understanding of its specific pathophysiology. However, high levels of oxidative stress, cortisol, inflammation, gut microbial dysfunction and genetic mutations related to mitochondrial dysfunction have been suggested as potential mechanisms relevant to OCD pathology.Reference Maia, Oliveira, Lajnef, Mallet, Tamouza and Leboyer4–Reference Turna, Grosman Kaplan, Anglin, Patterson, Soreni and Bercik6

Many of these proposed mechanisms may be modified by dietary quality or dietary intake. Vitamins and polyphenols in plant-based foods, as well as extra virgin olive oil and omega-3 in fish, have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects.Reference Godos, Currenti, Angelino, Mena, Castellano and Caraci7 Conversely, calorie-dense foods, hydrogenated fats and added sugars are linked with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.Reference Godos, Currenti, Angelino, Mena, Castellano and Caraci7 Foods with high fibre, prebiotics and probiotics may modulate gut microbiota, whereas Mediterranean and other plant-rich diets have been linked with increased microbiota diversity.Reference Godos, Currenti, Angelino, Mena, Castellano and Caraci7 With respect to mitochondrial dysfunction, preclinical evidence suggests that high-fat diets may be associated with abnormal biogenesis of mitochondria, which is linked with greater free radical production.Reference Marx, Lane, Hockey, Aslam, Berk and Walder8

Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies have found that improving dietary quality results in significant reductions in depressive symptoms, especially when interventions are delivered by health professionals.Reference Firth, Marx, Dash, Carney, Teasdale and Solmi9,Reference Lassale, Batty, Baghdadli, Jacka, Sánchez-Villegas and Kivimäki10 However, it must be noted that most of these studies used samples with non-clinical depression and significant heterogeneity was encountered in subgroup analyses.Reference Firth, Marx, Dash, Carney, Teasdale and Solmi9,Reference Lassale, Batty, Baghdadli, Jacka, Sánchez-Villegas and Kivimäki10 Given considerations such as these, recommendations for modifying diet as part of managing mental illness have begun receiving international recognition in several national health policy documents and psychiatric clinical guidelines.Reference Firth, Solmi, Wootton, Vancampfort, Schuch and Hoare11

Diet and OCD

Dietary and nutritional concerns in OCD may be additionally important given the increased risk of chronic disease in patients with OCD. Increased risk of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, which are substantially influenced by dietary habits, have been reported in individuals with OCD.Reference Isomura, Brander, Chang, Kuja-Halkola, Rück and Hellner12 Furthermore, an Italian cross-sectional study of 104 patients with OCD found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher than the general population, with its risk increasing with prolonged antipsychotic use.Reference Albert, Aguglia, Chiarle, Bogetto and Maina13 At the physiological level, a study comparing 104 patients with severe OCD symptoms and 101 patients admitted to a psychiatric unit (with predominantly psychotic and mood disorders) found that the patients with OCD had significantly higher levels of blood cholesterol and creatinine, despite being on lower doses of antipsychotics.Reference Drummond, Boschen, Cullimore, Khan-Hameed, White and Ion14 Although it is well-established that individuals with depression, bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders often have poor dietary quality, no published study to date has investigated the overall dietary quality of individuals with OCD.Reference Marx, Lane, Hockey, Aslam, Berk and Walder8,Reference Teasdale, Ward, Samaras, Firth, Stubbs and Tripodi15

Studies have reported that the serum levels of certain micronutrients, such as serum vitamin B12, zinc, iron and magnesium, are lower in people with OCD compared with healthy controls, although the relationship with folic acid or folate with OCD has been less conclusive.Reference Atmaca, Tezcan, Kuloglu, Kirtas and Ustundag16–Reference Yazici, Percinel Yazici and Ustundag20 Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that zinc and magnesium may have a significant and negative correlation with depressive symptoms in women, but not men, although clinical samples are also required.Reference Maserejian, Hall and McKinlay21–Reference Thi Thu Nguyen, Miyagi, Tsujiguchi, Kambayashi, Hara and Nakamura23 Lastly, a small (n = 11) RCT found augmenting fluoxetine (20 mg/day) with zinc sulphate (440 mg/day) achieved significant decreases in Yale Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores after 8 weeks.Reference Sayyah, Olapour, Saeedabad, Yazdan Parast and Malayeri24 Although this emerging research is promising, larger sample sizes with more robust study designs are needed to elucidate the importance of these micronutrients in OCD.

As little is known about the overall dietary quality and macro and micronutrient intake in patients with OCD, the present study evaluated the nutrient intake and dietary quality in adults with OCD by using a standardised dietary quality assessment. Regression analyses were employed to determine whether the severity of OCD symptoms correlated with dietary quality and nutrient intake. Given the emerging data suggesting that patients with OCD have impaired markers of physical health, we hypothesised that nutrient intake and dietary quality would be worse in patients with OCD compared with the general population. Additionally, consistent with evidence in studies of depression symptoms,Reference Maserejian, Hall and McKinlay21–Reference Thi Thu Nguyen, Miyagi, Tsujiguchi, Kambayashi, Hara and Nakamura23 we hypothesised that there would be a negative relationship between OCD severity and zinc and magnesium intake in women, but not men.

Method

Study overview, design and procedure

Baseline data were drawn from participants with DSM-5-diagnosed OCD in two separate studies, and were used to investigate the relationship between OCD severity, nutrient intake and dietary quality. The first study (n = 98) was a phase 3, multicentre, 24-week, randomised, double blind placebo-controlled trial studying the effects of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) augmentation (2–4 g/day) compared with placebo in the treatment of OCD.25 Participants were recruited between 2016 and 2020 at The Melbourne Clinic, Melbourne (University of Melbourne); Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane (University of Queensland); and NICM Health Research Institute, Westmead (Western Sydney University). Eligibility criteria included being aged 18–75 years, capacity to consent to the study and follow its procedures, primary DSM-5 diagnosis of OCD and a score of 16–31 on the Y-BOCS. Participants were excluded if they had bipolar disorder, a psychotic disorder, a primary diagnosis of obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorder, severe depression, alcohol/substance misuse, treatment refractory OCD, were currently engaging in intensive psychological therapies for OCD or were taking medications with known or suspected negative interactions with NAC (e.g. activated charcoal, nitroglycerine, chloroquine). Other exclusion criteria included allergy to any component of the investigational product, serious and/or unstable medical conditions, recent gastrointestinal ulcers, pregnancy and lactation, participation in any other interventional study and cessation of primary OCD medication. Participants were also required to remain on the same dose of psychotropic medication/s for their OCD throughout the study period.

The second study (n = 28) was a 20-week, open-label pilot study that assessed the effectiveness and safety of a nutraceutical formulation for patients with treatment-resistant DSM-5-diagnosed OCD.Reference Sarris, Byrne, Oliver, Cribb, Blair-West and Castle26 Participants were recruited at the same sites as the first study described above, between 2017 and 2020. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18–75 years, capacity as well as desire to consent to the study and follow its procedures, a primary DSM-5 diagnosis of moderate-to-extreme OCD (Y-BOCS ≥ 16), inadequate responses to at least three trials of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and at least one augmentation strategy as well as engagement in adequate OCD-specific cognitive–behavioural therapy. Participants were excluded if they had bipolar disorder, a psychotic disorder, a primary diagnosis of obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders, severe depression, alcohol/substance misuse, suicidal ideation (defined as Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (SIGH-D) item score ≥3), serious and/or unstable medical conditions or allergies to the nutraceuticals studied (NAC, L-theanine, zinc, selenium, magnesium and pyridoxal-5’-phosphate).

Participants in both studies were recruited via invitation letters to former attendees of an OCD in-patient programme at The Melbourne Clinic, clinician referrals at all three recruitment sites, as well as radio and social media advertisements. Those who were interested in the study completed a brief phone screening assessment with a trained research assistant to assess study suitability; baseline screening appointments were subsequently scheduled for those who were eligible. Following written informed consent, participants were assessed by a trained research assistant at baseline, using the measures outlined below. Both studies used the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 to confirm OCD diagnoses. The Y-BOCS and SIGH-D were also administered at baseline. These data were used in the current subanalysis. Participants were asked to complete the Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies version 3.2 at home. However, of the 126 participants, a large proportion (n = 41) did not complete the survey, as it was not a compulsory component of the trial.

Measures

Y-BOCS

The Y-BOCS consists of the Yale Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale-Severity Scale (Y-BOCS-SS) and the Yale Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale-Symptom Checklist.Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Delgado and Heninger27,Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill28 The Y-BOCS-SS was the primary outcome measure in both parent trials.

The Y-BOCS-SS is a ten-item clinician-administered instrument that rates the severity of obsessive and compulsive symptoms (e.g. time spent on obsessions) on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (none or minimal severity) to 4 (greatest severity).Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill28 The sum of these ten items allows an individual's OCD to be categorised as either subclinical (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–23), severe (24–31) or extreme (32–40). The Y-BOCS-SS demonstrates good psychometric properties and is considered to be the gold standard in assessing OCD symptom severity.Reference Grabill, Merlo, Duke, Harford, Keeley and Geffken29

DQES version 3.2

The DQES version 3.2 is an online self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) developed by the Cancer Council Victoria, Australia. It was developed and validated to assess dietary and nutritional intake in Australian adults.Reference Bassett, English, Fahey, Forbes, Gurrin and Simpson30 The DQES version 3.2 consists of 142 food and beverage items and provides estimates of 98 nutrient indices, including macronutrients, micronutrients, glycaemic index, fibre and alcohol.Reference Zhang and Downie31

Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults – 2013

The Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults – 2013 (HEIFA-2013) is a gender-specific index for dietary quality that assesses adherence to serving size recommendations outlined in the 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines.Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32 The index consists of 11 components, nine of which are scored from zero to ten (i.e. discretionary foods, vegetables, fruits, grains, meat and its alternatives, dairy and its alternatives, saturated fat, sodium, added sugar) and two of which are scored from zero to five (i.e. water and alcohol intake).Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32 Higher scores reflect intake of a certain food group that more closely matches the recommended serving size, with the highest possible total score being 100.Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32 The HEIFA-2013 has been tested for criterion validity and internal consistency and has been used numerous times in adult populations.Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32,Reference Hlaing-Hlaing, Pezdirc, Tavener, James and Hure33 In this study, nutrient intakes as measured by the DQES version 3.2 were used to score each participant's dietary quality.

Other measures

Other measures included the Dimensional Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (DOCS), 17-item SIGH-D, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Sheehan Disability Scale, Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGIS) and World Health Organization-Quality of Life-BREF. Blood pressure and body mass index measurements were also taken at baseline.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The first trial received ethical clearance through the Human Research Ethics Committees (HREC) of The Melbourne Clinic Research Ethics Committee (HREC number 279), The University of Queensland Medical Research Ethics Committee (HREC number 2016001720) and Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC number H12181). The second trial received ethical clearance through The Melbourne Clinic Research Ethics Committee (HREC number 290), The University of Queensland Medical Research Ethics Committee (HREC number 2018000339) and Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC number H12331). All components of both parent trials were carried out in line with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and were preregistered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (identifiers ACTRN12616000847415 and ACTRN12617001140347, respectively). Written and informed consent was provided by a signature to the consent form after a trained research assistant explained the study to the participant.

Statistical analyses

Sociodemographic characteristics were compared between the groups that completed and did not complete the DQES version 3.2, using Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. For certain mental health scales (e.g. DOCS, BAI), participants occasionally missed items when completing the questionnaire. Missed items were imputed with predictive mean matching (R package ‘mice’).34 Under 5% of items were imputed.

The relationship between OCD severity, dietary quality and nutrient intake was assessed with linear regression. Model 1 assessed whether greater OCD severity was related to a greater intake of a given nutrient, adjusting for gender, age and energy intake. Sensitivity analyses were also performed with depression (using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) and treatment resistance included as covariates to determine whether OCD severity was associated with nutrient intakes after accounting for depression symptoms and other covariates (Supplementary Material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1039). Assumptions of linear regression were checked via residual versus fitted plots.

The HEIFA-2013 scores were calculated with Microsoft Excel 365 for Windows, and all other statistical analyses were conducted on IBM SPSS Statistics 27 for Windows and R version 4.0.4 for Windows. Statistical significance was regarded as P < 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics and psychological features

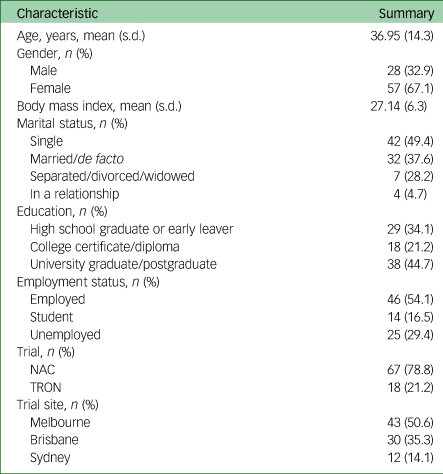

Of the 126 participants across both parent studies, 85 completed the DQES version 3.2 and were hence included in this substudy. Sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants who did not complete the DQES version 3.2 reported significantly higher total Y-BOCS (meanno-DQES = 24.53 v. meanDQES = 22.73, P = 0.025) and CGIS (meanno-DQES = 4.39 v. meanDQES = 4.13, P = 0.034) scores than those who completed the DQES. However, there were no statistically significant differences for any of the other sociodemographic characteristics and psychological features assessed, such as gender, age and educational status. Of the 85 participants, the mean age was 36.95 years (s.d. = 14.3), 67.1% were women, and the mean body mass index was 26.94 (s.d. = 6.3).

Table 1 Participant characteristics

NAC, N-acetylcysteine; TRON, Treatment of Refractory Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with Nutraceuticals.

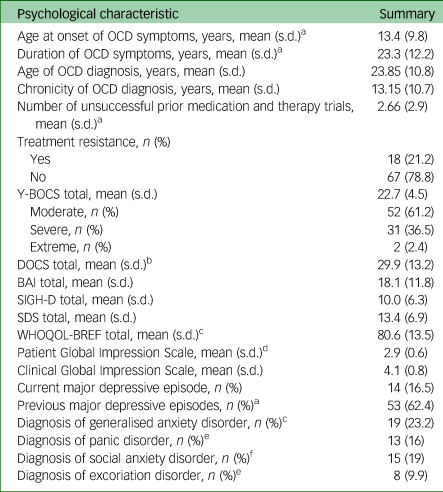

Table 2 reports the main psychological features of the 85 participants. The mean age of OCD symptom onset was 13.4 years, with the mean age of OCD diagnosis being 23.8 years. Participants on average reported OCD symptoms for 23.3 years and having a diagnosis of OCD for an average of 13.1 years. Participants had on average 2.6 unsuccessful medication and therapy trials, and 21.2% of all participants were treatment-resistant.

Table 2 Participant psychological features

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; Y-BOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale; DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive–Compulsive Scale; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; SIGH-D, Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF.

a. n = 2 missing.

b. n = 8 missing.

c. n = 3 missing.

d. n = 1 missing.

e. n = 4 missing.

f. n = 6 missing.

From the Y-BOCS scores, over half (61.2%) reported moderate OCD symptoms, 36.5% reported severe OCD symptoms, whereas 2.4% reported extreme OCD symptoms. The mean DOCS score (29.9) was above the minimum that is suggestive of a diagnosis of OCD.Reference Shohag, Ullah, Qusar, Rahman and Hasnat18–Reference Yazici, Percinel Yazici and Ustundag20 The mean BAI score (18.1) suggests that participants were moderately anxious on average, with 22.4% and 14.1% of the sample reporting a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder, respectively. Over half (62.4%) of the sample reported a previous major depressive episode, with 16.5% experiencing current clinical depression.

Participant dietary intake and quality

Table 3 shows the mean macronutrient and micronutrient dietary intakes in this sample by total and gender, as well as the HEIFA-2013 dietary quality scores as summed by the individual food products in the DQES version 3.2. Estimates for the daily recommended intake in those aged 31–50 years are also outlined where possible, as per Australian guidelines.Reference National Health35,36 The mean energy intake was 8297 kJ/day (s.d. = 2628.1). Men consumed 9439.47 kJ/day (s.d. = 2697.85), which is greater than the recommended 8700 kJ average energy intake level that is commonly displayed on Australian nutrition information panels.Reference Bracci, Keogh, Milte and Murphy37 Most participants (90.6%) ate the recommended daily serves of unsaturated fat (four serves for men, two serves for women). However, most participants (60%) consumed >10% of saturated fat as part of their total daily energy intake (mean 12.6%). Both men and women consumed more magnesium than the upper limit suggested (350 mg/day), although exceeding this value has not been shown to produce adverse effects.Reference Grabill, Merlo, Duke, Harford, Keeley and Geffken29 The mean sodium intake was 2172.13 mg (s.d. = 805.5); however, men consumed 2556.05 mg/day (s.d. = 920.82), which is above the recommended maximum of 2300 mg/day.Reference National Health35 The mean HEIFA-2013 score for dietary quality was 59.9 (s.d. = 13.7).

Table 3 Participant dietary intake and quality with Australian recommended intake levels

HEIFA-2013, Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults – 2013.

a. Recommended daily intake unless otherwise stated.

b. Linoleic acid; recommended daily intakes are taken from the Nutrient Reference Values for Australian and New Zealand.

c. Adequate intake.

Associations between dietary intake/quality and total Y-BOCS score

Table 4 shows the associations between total Y-BOCS score, nutrient intake and dietary quality, using adjusted regression analyses. There was some weak (albeit non-significant) evidence suggesting that a greater Y-BOCS score was associated with a lower intake of alcohol (β = −0.58 g/day, 95% CI −1.26 to 0.10, P = 0.09), caffeine (β = −12.99 mg/day, 95% CI −26.07 to 0.09, P = 0.051) and magnesium (β = −5.46, 95% CI −11.42 to 0.50, P = 0.07) after accounting for gender, age and total energy intake. There was no clear evidence that OCD severity was associated with the intakes of any of the other assessed nutrients. Furthermore, the total Y-BOCS score was not associated with dietary quality scores (β = 0.06, 95% CI −0.58 to 0.70, P = 0.85).

Table 4 Associations between total Y-BOCS score and dietary intake/quality

Y-BOCS, Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; HEIFA-2013, Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults – 2013.

a. Adjusted for gender, age and energy intake

b. Per unit increase in total Y-BOCS score.

There was also some weak albeit non-significant evidence demonstrating that the relationship between OCD severity and magnesium intake varied with gender (interaction estimate of 13.74 mg/day, 95% CI −2.55 to 30.0, P = 0.097). In men, greater OCD severity was associated with greater magnesium intake (interaction estimate of 7.32 mg/day, 95% CI −6.85 to 21.50, P = 0.298), whereas in women, greater OCD severity was associated with lower magnesium intake (interaction estimate of −6.15 mg/day, 95% CI −15.45 to 3.15, P = 0.191), although non-significantly in each case. There was no evidence that the relationship between OCD severity and zinc intake differed by gender (interaction estimate of 0.19 mg/day, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.56, P = 0.317).

No substantive changes were seen in sensitivity analyses that included depression diagnosis as a covariate (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1039). In a further sensitivity analysis, including age, gender, total energy intake and treatment resistance as covariates, we found a statistically significant inverse association between OCD severity and caffeine (β = −15.50, 95% CI −28.88 to −2.11, P = 0.024), as well as an inverse association between OCD severity and magnesium (β = −6.63, 95% CI −12.72 to −0.53, P = 0.034). We additionally assessed whether OCD chronicity (years since diagnosis) was associated with nutrient intakes by using a further regression model, adjusted for age, gender, total energy intake and total Y-BOCS score. However, there was no evidence that OCD chronicity was associated with intakes of any nutrient (all P > 0.05; results not shown).

Discussion

This study assessed dietary quality and nutrient intake in a sample of adults with OCD. Macronutrient intake in this sample largely aligned with Australian dietary guidelines, whereas dietary quality scores were higher than in previous studies of healthy samples. There was no significant association nutrient intake and dietary quality variables with OCD severity when adjusted for age, gender and total energy intake. However, in a sensitivity analysis which additionally included OCD treatment resistance as a covariate, OCD severity was inversely associated with caffeine (P = 0.024) and magnesium (P = 0.034) intake.

Average daily intake levels of macronutrients and micronutrients were largely in line with the 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines, except for sodium and energy intake in men. Counter to our hypothesis, compared with a randomly sampled Australian population that were surveyed with a similar version of the DQES (3.0 and 3.1), the adult OCD sample in the present study had lower average daily intakes of total energy and macronutrients (but reported a higher consumption of alcohol; 7.93 g/day in this sample compared with 3.6 g/day in the other sample).Reference Fulton, Baldock, Coates, Williams, Howe and Haren38

In previous research evaluating dietary intake in individuals with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, mean total energy and carbohydrate intake levels were higher in most of these samples, along with their respective control groups, than the OCD sample in the present study.Reference Jahrami, Saif, AlHaddad, MeA-I, Hammad and Ali39–Reference Strassnig, Brar and Ganguli41 Our OCD sample reported higher levels of monounsaturated fat intake than studies evaluating individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.Reference Jahrami, Saif, AlHaddad, MeA-I, Hammad and Ali39,Reference Bly, Taylor, Dalack, Pop-Busui, Burghardt and Evans42 These findings may be explained by the predominance of women in our sample, who have lower caloric intakes than men. However, it is difficult to draw direct conclusions when evaluating these studies, given the different measures of dietary intake and study locations.

The mean dietary quality in this sample was 59.9 (s.d. = 13.7) out of a total maximum score of 100. This finding was unexpectedly high, given that three other studies using the HEIFA-2013 in non-clinical samples reported mean dietary quality scores of between 45.5 and 53.84.Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32,Reference Grech, Sui, Siu, Zheng, Allman-Farinelli and Rangan43,Reference Roy, Rangan, Hebden, Yu Louie, Tang and Kay44 There are a few potential reasons why the mean dietary quality in this sample may have been higher than in previous studies. Roy et al used a weighted food record, which is a more accurate measure of dietary intake.Reference Roy, Rangan, Hebden, Yu Louie, Tang and Kay44 Conversely, FFQs have been found to overreport intakes of healthy food and underreport intakes of unhealthy foods, meaning that the methods used in the present study may have overestimated the HEIFA-2013 score.Reference Johansson, Hallmans, Wikman, Biessy, Riboli and Kaaks45 Second, the age ranges of two of the studies were exclusively young adults and university students, respectively, and thus are limited in comparability.Reference Roy, Hebden, Rangan and Allman-Farinelli32,Reference Roy, Rangan, Hebden, Yu Louie, Tang and Kay44 Finally, there may be a genuine difference between patients with OCD and healthy controls, given the lower energy, protein and carbohydrate intakes compared with the two healthy control groups described earlier. It may be hypothesised that the large diagnostic comorbidity between OCD, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (because of the trait commonality of perfectionism and cognitive rigidity in these disorders) may contribute to these findings.Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Fernández-Aranda, Raich, Alonso, Krug and Jaurrieta46 However, we did not have sufficient data to examine this, and further research is required to explore this hypothesis.

We did not find a statistically significant correlation between total energy and macronutrient intake with OCD severity in this study, and therefore our hypothesis that OCD severity is associated with a higher macronutrient intake was not supported. One potential reason for the null findings could be related to selection bias. Participants with more severe OCD were relatively less likely to complete the DQES, and these participants might additionally have had poorer dietary intake. It is noteworthy that our positive albeit non-significant associations between total energy and macronutrient intake with OCD severity broadly aligns with a large population-scale analysis that found that people with more severe mental illness (i.e. major depressive disorder, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) reported higher caloric and macronutrient intake compared with healthy controls.Reference Firth, Stubbs, Teasdale, Ward, Veronese and Shivappa47 Therefore, further research in this area is warranted, given our findings were inconclusive.

Regression modelling identified an inverse association between OCD severity and caffeine consumption, when adjusting for age, gender, total energy intake and treatment resistance. Although this result is preliminary and has not been adjusted for multiple tests, this result is consistent with emerging data from two short-term RCTs (5 weeks, n = 24, dextroamphetamine versus caffeine; 8 weeks, n = 62, caffeine versus placebo) that reported significant reductions in OCD symptoms when caffeine was augmented in adults with treatment-resistant OCD.Reference Koran, Aboujaoude and Gamel48,Reference Shams, Soufi, Zahiroddin and Shekarriz-Foumani49 Additionally, in our recently completed open-label Treatment of Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with Nutraceuticals (TRON) trial, we found that treatment response to a nutraceutical combination was substantially higher in participants with high levels of caffeine intake relative to those with low caffeine intake in a treatment resistant OCD sample.Reference Sarris, Byrne, Oliver, Cribb, Blair-West and Castle26 It has been hypothesised that caffeine's modulation of tryptophan, serotonin and noradrenaline production via adenosine A1 and A2 receptor antagonism is also implicated in the pathophysiology of OCD.Reference Shams, Soufi, Zahiroddin and Shekarriz-Foumani49 However, larger samples and longer-term follow-up trials are required to determine whether a dose–response relationship exists.

In the regression models that included covariates for age, gender, total energy intake and OCD treatment resistance, an inverse association between magnesium intake and OCD severity was also noted. However, one other case–control study found no correlation between total Y-BOCS score and serum magnesium in a sample of 48 adults with OCD.Reference Shohag, Ullah, Qusar, Rahman and Hasnat18 However, comparisons with this study are limited by different study locations, gender ratios and methods of measuring magnesium levels. Given glutamate dysfunction has been implicated in the neurobiology of OCD and magnesium is linked with glutaminergic signal modulation, further trials elucidating this relationship in large clinical samples are warranted.Reference Maia, Oliveira, Lajnef, Mallet, Tamouza and Leboyer4,Reference Botturi, Ciappolino, Delvecchio, Boscutti, Viscardi and Brambilla50

Linear regression modelling also demonstrated tentative evidence that the relationship between OCD severity and magnesium intake may vary with gender, with inverse associations in women and positive associations in men (albeit non-significantly). These findings are noteworthy, given that two large population-based studies found significant, inverse associations between depressive symptoms and dietary magnesium intake in women, but not men.Reference Sun, Wang, Li and Zhang22,Reference Thi Thu Nguyen, Miyagi, Tsujiguchi, Kambayashi, Hara and Nakamura23 Larger samples of OCD cohorts with matched control groups are needed to elucidate these preliminary findings further.

Our findings are in partial agreement with the small body of literature looking at micronutrients and trace elements in relation to OCD. We found no significant associations between OCD severity and calcium, vitamin D, iron, zinc and folate intake, which largely aligns with previous case–control studies comparing these micronutrients with individuals with OCD.Reference Shohag, Ullah, Qusar, Rahman and Hasnat18–Reference Yazici, Percinel Yazici and Ustundag20 However, a study using a small sample of 23 adult patients with OCD found a significant negative relationship between serum folate and total Y-BOCS scores.Reference Atmaca, Tezcan, Kuloglu, Kirtas and Ustundag16 In contrast with our findings, another case–control study found a negative correlation between total Y-BOCS scores and serum vitamin B12 and vitamin D in 52 children and adolescents with OCD.Reference Esnafoğlu and Yaman17 Given that these studies predominantly used serum level measurements of these micronutrients and were conducted in different study locations as well as contexts, comparability may be limited.

This study has many strengths. It is the first to describe in detail the dietary quality and nutrient intake in an adult sample with OCD. We were also able to compare dietary quality and nutrient intake to OCD severity, controlling for multiple confounding variables. Lastly, we were able to collect data from participants across multiple study sites. However, this study is not without its limitations. We used a cross-sectional data-set, which does not longitudinally assess dietary quality in relationship to OCD symptoms nor does it allow an assessment of causation. This study also lacks a control group with an identical FFQ to make proper comparisons using quantitative methods, as we were unable to locate data with the same questionnaire. The DQES version 3.2 also relies on recalling what foods were eaten in the past, which is subject to measurement bias and is likely to have underestimated nutrient intakes and overestimated the dietary quality scores. It is also unclear what role the presence of OCD might have on reporting of dietary intake. Finally, our sample size was modest, and we did not have enough participants across all obsessive–compulsive-related disorders to account for these potential confounders. Future research should be longitudinal in nature, use a larger sample size as well as weighted food records as a more accurate measure of nutrient intake, and employ a control group to make between-group comparisons.

In conclusion, the nutrient intake in our sample of patients with OCD largely aligned with recommended Australian dietary guidelines. Dietary quality was comparable with healthy samples, but limitations must be noted. Although OCD severity was inversely associated with caffeine and magnesium intake in one sensitivity analysis accounting for OCD treatment resistance, our findings largely showed that OCD severity had a minimal effect on nutrient intake and dietary quality. Future studies using a larger sample size and a control group will help better elucidate the relationship between nutrient intake and dietary quality in patients with OCD.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1039

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.S., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Graham Giles of the Cancer Epidemiology Division, Cancer Council Victoria, for permission to use the Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies (version 3.2).

Author contributions

T.P.N., L.C., G.O. and J.S. were involved in drafting the first iteration of the manuscript. T.P.N. and L.C. analysed the data. All other authors participated in the editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

T.P.N. was supported by a Western Sydney University Summer Research Scholarship. J.S. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Clinical Research Fellowship (number APP1125000). O.M.D. is supported by an R.D. Wright NHMRC Biomedical Career Development Fellowship (number 1145634). M.B. is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (number 1156072). C.E. is supported by an endowment from the Jacka Foundation of Natural Therapies. NHMRC APP1104460.

Declaration of interest

M.B. has received Grant/Research Support from the National Institutes of Health, Cooperative Research Centre, Simons Autism Foundation, Cancer Council of Victoria, Stanley Medical Research Foundation, Medical Benefits Fund, National Health and Medical Research Council, Medical Research Futures Fund, Beyond Blue, Rotary Health, A2 milk company, Meat and Livestock Board, Woolworths, Avant and the Harry Windsor Foundation; has been a speaker for Abbot, AstraZeneca, Janssen and Janssen, Lundbeck and Merck; and served as a consultant to Allergan, AstraZeneca, Bioadvantex, Bionomics, Collaborative Medicinal Development, Janssen and Janssen, Lundbeck Merck, Pfizer and Servier – all unrelated to this work. O.M.D. is a R.D. Wright Biomedical NHMRC Career Development Fellow (APP1145634) and has received grant support from the Brain and Behavior Foundation, Simons Autism Foundation, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Deakin University, Lilly, NHMRC and ASBDD/Servier. She has also received in kind support from BioMedica Nutracuticals, NutritionCare and Bioceuticals. All other authors declare no competing interests.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.