CHD is diagnosed in approximately 1% of births in the United States of America; a substantial and increasing proportion of these diagnoses is made prenatally. Reference Quartermain, Pasquali and Hill1,Reference Bakker, Bergman and Krikov2 Physicians may assume that prenatal diagnosis is beneficial, allowing parents additional emotional processing and decision making about continuing pregnancy and intended delivery location. Reference Hilton-Kamm, Sklansky and Chang3–Reference Franklin, Burch, Manning, Sleeman, Gould and Archer8 Prenatal diagnosis does lead to improved parental understanding of CHD at the time of Neonatal ICU (NICU) discharge. Reference Williams, Shaw and Kleinman9 However, studies have demonstrated that receiving a prenatal diagnosis of CHD, on average, elicits greater parental psychological stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms at hospital discharge and for months after birth when compared with receiving a postnatal diagnosis. Reference Stapleton, Dondorp, Schroder-Back and de Wert10–Reference Skreden, Skari and Malt20 Researchers have called for longitudinal studies of parents to begin to understand this phenomenon. Reference Fonseca, Nazare and Canavarro14,Reference Carlsson, Marttala, Wadensten, Bergman and Mattsson21–Reference Donofrio, Moon-Grady and Hornberger26 Prior qualitative studies have begun to investigate the experience of mothers after receiving a prenatal diagnosis; Reference Carlsson, Marttala, Wadensten, Bergman and Mattsson21,Reference Lalor, Begley and Galavan27–Reference Carlsson, Starke and Mattsson35 this study extends that knowledge by tracking parents’ experience over time from prenatal diagnosis until after birth.

The first publication from this study focused on the prenatal parental experience after CHD diagnosis, especially sources of stress, and identified uncertainty as a pervasive theme, regarding both concrete questions about scheduling, logistics or next steps, and long-term unknown variables. Reference Harris, Brelsford, Kavanaugh-McHugh and Clayton36 In order to identify interventions to improve parental support, we sought to understand how the parental experience, especially emotional processing and coping mechanisms, evolves over time from prenatal diagnosis through the postpartum period. This study sheds light on what may be occurring when parents talk about having hope, as distinct from denial, wishes, or naïve optimism, in order to help clinicians to respond to and provide support for families more effectively.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a single-centre, longitudinal, qualitative study of pregnant mothers and their partners or support persons seen in Fetal Cardiology Clinic at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital for probable complex CHD. Reference Harris, Brelsford, Kavanaugh-McHugh and Clayton36 Patients were enrolled prior to the pregnant mother’s first consultation appointment. With the consent of the fetal cardiologists and the parents, in-clinic prenatal counseling was observed at the initial prenatal visit and one follow-up visit.

One investigator (KWH) conducted audio-recorded semi-structured interviews with each participant at three time points, one after each observed prenatal visit and one postnatally. Written consent was obtained from all patients at enrollment, and verbal permission prior to each interview. The average interview length was 27 minutes. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Patients were enrolled from May to August, 2019; 31 families were approached, 5 families declined enrollment; the participation rate was 84%. Five families were excluded following normal echocardiograms. Of the 37 individuals from 21 families who enrolled and were eligible, 10 were lost to follow-up prior to being interviewed. Active patients included 27 individuals from 17 families; 62 interviews were conducted from May, 2019 to January 2020 (see Fig 1). The median timing for prenatal interviews was 13 days after a fetal cardiology clinic visit, and for postnatal interviews, 30 days after birth.

Figure 1. Study cohort flowchart, including initial enrollment and participation in semistructured phone interviews over time.

A semi-structured interview guide with 13 primary questions explored patients’ overall experience, anticipation of the future, factors influencing their experience, and feelings of empowerment (see Appendix). This paper reports responses to questions about emotional processing, coping, and support. Nearly all interviews were conducted on the phone with individual patients; one interview was conducted in-person and with both a mother and father present, per their request.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were analysed using NVivo 12 (QSR International). An iterative process was used to code and analyse data using an applied thematic analysis approach, following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guidelines for qualitative studies. Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey37 One author (KWH) developed an initial structural and content codebook including code definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and illustrative examples. Reference MacQueen, McLellan, Kay and Milstein38 Two authors (KWH and KMB) systematically refined the codebook through an iterative process of application, discussion, and revision. KWH was the primary coder for all transcripts. KMB and CMHA each independently reviewed one-fifth of transcripts at fixed intervals to maintain >80% interrater reliability. Discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Post hoc, themes were compared across time (prenatal and postnatal interviews) and diagnosis (higher and lower risk of mortality).

Participant quotes are identified first by family number (1–21), then by participant role (M = mother, F = father, O = any other support person), time point of interview (1–3; 1 and 2 occurred prenatally and 3 occurred postnatally), and finally by risk of mortality (H = higher, L = lower). Thus, 5.F.2.H indicates a quote from a father of family number 5 during the second interview with a higher risk of mortality diagnosis.

Results

Patient characteristics

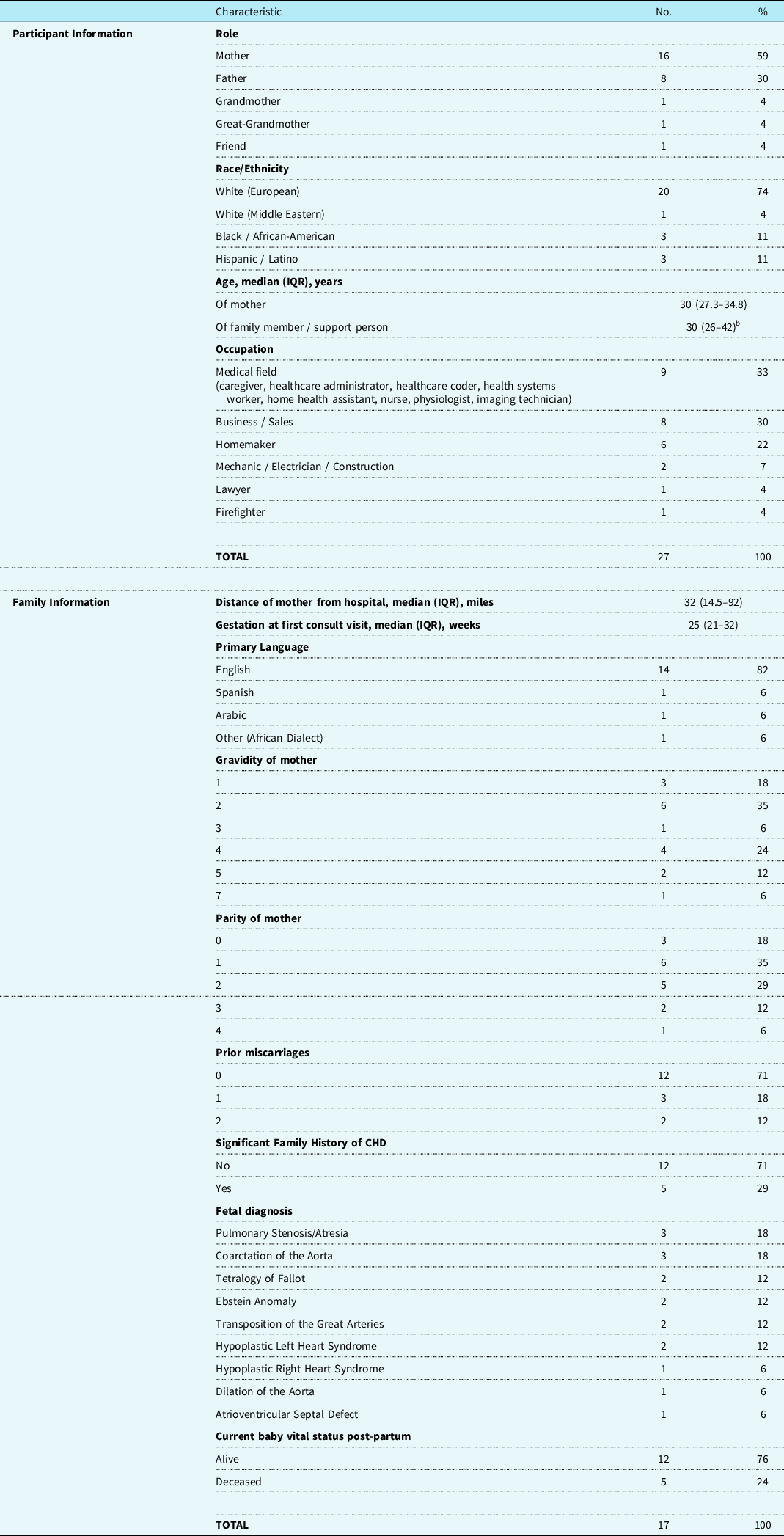

Patients represented a range of demographic characteristics (Table 1). Most interviewees were mothers (16 [59%]) or fathers (8 [30%]). The majority self-identified as White (21 [78%]). The primary language spoken was English (14 [82%]); only one family utilised a language interpreter. Most mothers had other live children (14 [82%]) and no known family history of CHD (12 [71%]). Initial diagnoses included a variety of cardiac anomalies, which varied in risk of mortality (Table 2). Reference Allan and Huggon39

Table 1. Demographic characteristics a

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

a Table originally printed in Harris KW, Brelsford KM, Kavanaugh-McHugh A, Clayton EW. Uncertainty of Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2020.

b Three missing data points, as ages of two fathers and one great-grandmother unknown.

Table 2. Diagnoses included in this study grouped by mortality risk.

a Allan LD, Huggon IC. Counselling following a diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Prenatal diagnosis. 2004;24(13):1136–1142.

* Baby died after birth.

Considerations and approaches prior to delivery

Accepting the diagnosis

Ultimately, all patients demonstrated understanding of the medical aspects of their child’s diagnosis and prognosis. While many shared their desire for a different reality, saying for example, “I wish my baby was [fine]” (8.M.1.L) or “I wish I knew when I was in the first trimester” (6.M.1.H), no one expressed or implied denial. Furthermore, they sought truth from providers, not false hope. One said, “I don't need the sugarcoating. I just need to know how we think it’s going to go, and then I can be pleasantly surprised if it goes well” (10.F.2.H).

Families with diagnoses consistent with lower mortality risk said, “we’ve kind of accepted [it]” (8.M.1.L), and “however she comes into the world, we will love her.” (9.O.1.L). Families in the higher mortality risk group agreed, “we do know that there’s a 20% chance that he may not make it, but…what will be, will be” (1.O.2.H); and “after I came to the realisation that it was true… [we] had to accept it” (18.F.1.H).

Sense of control

When asked how much control they had, at least one from each family, of both higher and lower-mortality risk groups, discussed lack of control over their baby’s health: “It’s…out of my control. It’s…up to doctors and [my baby]” (18.M.1.H); “I wish I had more control over that stuff” (21.M.1.H); “There’s nothing I could do that would change or influence the outcome” (3.M.1.L).

Parents identified a few things they could control, such as “emotions” (11.M.1.L), “thoughts and attitude” and “self-care” (12.M.2.L), “gathering information” (5.F.2.H), and making personal medical decisions (20.M.1.H; 9.M.1.L). One explained, “the control we have is to stay involved and do the things we’re supposed to do” (8.F.1.L) because “I have no control over… how the baby’s going to be, but…[only] how we’re going to react, and what we’re going to do moving forward” (8.F.2.L).

Preparation and resources

The majority of patients felt well-prepared for their child’s birth saying they received “everything… needed to be prepared” (1.O.3.H), “I was as prepared as I could be” (10.F.3.H), and “as ready as I [could] be” (21.M.2.H). They “were so grateful… [to know they] were going to have a heart baby” (12.M.3.L), saying “to know up front is a lot better” (9.M.1.L) and they would “rather be prepared” (3.M.1.L). They appreciated “knowing the possibilities” (8.14.3.L) so “when something does happen, I can say, ‘okay, I was told about this’” (2.M.1.L).

Patients learned from repeated counseling by fetal cardiologists who “coached us… for several months before the birthing” (1.O.3.H). One mother said, “At the time, “I [didn't] understand why they have to explain it over and over, but now that I look back… I’m glad they did because I understand it a lot more” (1.M.3.H). Others felt “overwhelmed after the first appointment,” (3.M.2.L) as “the first time you hear it… you’re not catching everything that could happen… but I got more in depth [information] this [second] time” (8.M.2.L).

Around two-thirds of patients who had received a diagnosis with a lower mortality risk sought out information online. They felt like it was “helpful” (3.M.2.L) to “know there are other people that you could talk [to]” (9.M.3.L) and “to see encouraging stories” (12.M.1.L). One said, “the Facebook group… has made me feel like way better… just knowing that there’s other families there” (11.M.3.L). In contrast, around two-thirds of patients facing higher-mortality risk “stay[ed] away from the Internet” (13.M.3.H). These respondents trusted the information they received from providers, saying, “You guys are going to tell me everything that I need to know… there’s no telling what you might find on the internet” (1.O.3.H), and “I’m not going to be able to get on the internet and pick out the answers… I rely on [doctors] to have information” (10.F.2.H). “I’m going to listen to what the doctors say… because I feel like I’m handling it so well. I don't want to upset that balance” (5.M.1.H).

The role of hope

Regardless of the mortality risk of the diagnosis, families could simultaneously communicate possible death and hope for a positive outcome. While they were realistic about the future and their lack of control over many aspects of it, many families also “hope[d] for the best” outcome, whether probable or miraculous. “Even the doctor doesn't know if she’ll make it… I’m hoping for good” (6.M.1.H).

Beside waiting for the future when the medical team would intervene, many parents believed, “nothing will help at this time other than God” (7.F.1.L). One mother explained she was “trusting” in “my doctors and in God” (4.M.1.L). A father agreed: “Divine spirit and… medical background, that could definitely help…” (5.F.1.H). His wife said, “I’m just leaning on hope and faith at this point” (5.M.1.H), and later, “Even though things have gotten worse… if I get my healing miracle, I’ll get one, if not, I’ll deal with that when it comes” (5.M.2.H).

Emotional processing and coping

When asked how they are preparing for the future, nearly every participant in the lower-mortality risk group discussed childcare logistics, compared with only half of those in the higher-mortality risk group. Parents were planning for the “baby shower” (9.O.1.L) and “getting the nursery ready” (4.M.1.L), as well as maternity leave, “child care” (11.F.1.L), and the upcoming “added daycare cost” (8.F.1.L). One was grateful that “my in-laws are going to…be here and help out with our [older] daughter” (2.M.2.L). None of these families mentioned a possible bad outcome.

In contrast, three-quarters of families in the higher mortality risk group discussed their emotional preparation for a possible bad outcome when asked how they were preparing for the future. One said, “He’s going to be really sick” (1.O.1.H); “He’s either going to have multiple surgeries or a transplant… the sad part about [transplant] is that another baby has to die in order to give him a heart” (1.O.2.H). Others agreed, “It’s going to be hard… as the baby gets here” (20.O.1.H). “It’s going to be hectic” (10.M.2.H), “harder” (21.F.1.H) and “difficult… he’ll be in the ICU” (5.F.2.H). One said, “I can't have surgery for him and then lose him at five months, that’ll kill me. I’d rather them just let him pass away on his own, right after birth than me lose him that late” (5.M.2.H).

The majority of patients in the higher mortality risk group also described dealing with life prenatally in discreet, manageable increments: “Take it day by day, and then as the time comes closer, you have to take it hour by hour, and don't worry about tomorrow because today has enough worries” (21.M.3.H). Others discussed their commitment to “trying to be positive” (10.M.2.H) and “surround[ing] themselves [with] people that are not negative” (13.M.3.H) “to keep me positive…I refuse to mourn a baby still alive” (5.M.1.H). Some named distraction as an important coping mechanism – they tried to “stay busy” (10.M.1.H; 18.F.1.H), “to distract” themselves (13.M.3.H) “with other things, like work” (13.F.3.H), and to “not… think about it” (6.M.1.H; 21.F.1.H).

Considerations and approaches after the child was born

Postnatally, as details about the diagnosis and prognosis crystalised, families found that their role evolved and the support they sought from providers often changed.

Communication

In contrast to their excellent prenatal preparation, many patients, regardless of their child’s condition, discussed how communication in the hospital after birth could be improved. One mother expressed confusion over the discharge plan, “Where are we going? What are we doing? Who do we talk to?” (8.M.3.L). She also “wish[ed] they would have done something” to improve communication among teams (8.M.3.L). Others desired dedicated time with a smaller group of providers, “not the entire rounds” (11.F.3.L). One said, “The only thing I would want changed was how the doctors addressed parents during rounds… Several times I had no idea what was going on… I often had questions that didn't get answered” (20.M.3.H). Others agreed, “the terminology can become a little confusing” (10.F.3.H), “a lot of [it] I did not understand” (11.F.3.L).

Alternatively, when parents were familiar with the language and culture of the hospital, they seemed to feel more comfortable. Two mothers had prior children with CHD. One noted that having “previous knowledge…makes this experience better” because of clearer “expectations” about the upcoming steps and possibilities (21.M.2.H). While it was still “emotional” to be with her baby in the NICU, “the talks with the doctors and stuff, that wasn't as scary the second time around” (21.M.3.H).

Regardless, parents felt reassured by the team spirit of providers who reportedly say “I’m on your side, we’re going to do this together” (21.M.3.H). They also valued providers’ creating physical and emotional space to feel supported (20.M.3.H) and to process new information.

Evolving role of parents – assuming control

After birth, some families assumed a new role on the team. Whereas prenatally, they felt their role was to “standby, pray, and wait” (1.M.2.H), to trust in providers and to prepare for the uncertain future, postpartum, they often became more actively involved in decision making, such as by consenting for procedures. Before giving birth, one mother said “I don't know if I want that control” over “the decision on surgical intervention…I think I would feel guilty no matter what my decision was” (5.M.2.H). After birth, her posture changed. She advised future parents to be assertive, emphasising “not to feel like their opinion and their voice doesn't matter… speak up” and “if a doctor says what you have to do, ask why … If you don't know [what you want] … say you don't know, and you need time” (5.M.3.H). She explained, "I felt everything was really rushed… I didn't know what I had control over" (5.M.3.H). When asked specifically about their sense of control, others also expressed a desire to gain more control postpartum, when “it’s easier for me to wrap my mind around what we need to do” (3.M.3.L). One said, “This is my baby, I have to ask these questions, like, ‘why do we have to do this?’ … he was able to come off of [the nasogastric tube] a lot quicker because I asked that question” (21.M.3.H). As their role becomes more active, parents may require different communication and support from providers.

Discussion

In this study, we found when families received a prenatal diagnosis for a child, they appreciated transparent, thorough information from providers. They understood the diagnosis and prognosis, and subsequently developed realistic worries and fears. Reference Harris, Brelsford, Kavanaugh-McHugh and Clayton36 To be sure, parents in this study longed for a healthy baby, but they communicated their understanding of the probability of that outcome through their word choice. For example, these parents consistently used the word “wish” to refer to a clearly impossible desire, such as to change an event that had occurred in the past, like the formation of their child’s heart, a delay in their knowledge of the malformation, or even their child’s death having occurred postpartum.

Yet, at the same time, families hoped for the best possible outcome for their child, and they seemed to cope with their new reality by focusing on that positive possibility, even if the probability of its occurring was minuscule. Physicians may misperceive hope as naïve optimism, potentially a negative adaptation, or as evidence of misunderstanding, for example, by asking questions about the distant future for a child with a poor prognosis. However, prior literature has demonstrated that parents can be hopeful while not optimistic that their child will recover, Reference Sisk and Malone40 and even maintain hope for survival while understanding that their child will die. Reference Kaye, Kiefer and Blazin41 In this study, parents communicated acceptance around the high mortality risk, while often simultaneously relying on doctors and God, medicine, and faith as they “hope[d] for the best” – a “healing miracle” that may not come. This model of harmonious integration of prognostic awareness and hope has also been described in palliative care adult literature as an alternative to the historical understanding that hope can be unfounded or realistic, but not both at the same time. Reference Curtis, Engelberg and Young42

Through their hope, parents may actually demonstrate that they are informed and understand what is at stake death and suffering. As one father explained, “I am hopeful to have a fairly independent and capable child that would have a moderately long life expectancy,” and at the same time, “I don't want my kid to suffer for five years and then die” (10.F.1.H). Put differently, these parents develop “critical hope,” which Dale Jacobs explains is “hope that allows us to imagine what is possible” and combines “a vision of the future toward which we can work with ‘the scientific analysis of reality.’” Reference Jacobs43 Thus, Jacobs explains, critical hoping is distinct from wishing and from “naïve optimism,” in that “we cannot just wish for something to happen, but must instead think reflexively about the situation and how we can assert our agency.” Reference Jacobs43

Thus, parents’ focus on positivity as a coping mechanism is a manifestation of “critical hope.” They understand the uncertainties and realities of their situation and acknowledge their lack of control over their child’s health. They assert the limited control they do have by granting trust to the medical team, by refusing “to mourn a baby still alive” (5.M.1.H), and instead, by focusing on positivity and their day-to-day lives. Parents may believe these actions will help them realise the best possible unfolding of events in the future. Families in this study, especially those who received diagnoses with a high risk of mortality, demonstrated their comprehension of the uncertainty of that envisioned future by also emotionally preparing for a possible bad outcome. Many did not engage in social media because they wanted to avoid despair or unfounded optimism in response to another parent’s story that may be not factual or may not apply to their own unique situation. Instead, they relied on information provided to them by medical providers so they could be “realistic.” These families truly valued thorough, honest information from providers and did not feel it took away their hope.

Acknowledging the presence of conflicting emotions within hope, optimism, wish, and realism may help to identify interventions to better support positive parental adaptation. Certainly, some families use these terms in different ways, misunderstand the prognosis, and hold naïve optimism about the future. Future interventions may focus on helping providers to understand individual parents’ evolving conceptualisation of these key concepts in relation to their understanding of their child’s diagnosis. Ultimately, teasing out the meaning behind individuals’ communicated hopes may enhance effective communication.

In prior analysis of this data, we found that the experience of parents prenatally was defined by uncertainty around both concrete questions and long-term unknowns. Receiving answers to concrete questions about appointments, logistics, and future steps helped parents gain some sense of control. Reference Harris, Brelsford, Kavanaugh-McHugh and Clayton36 Our findings in this study support that earlier observation. Through their coping strategies, families sought out a sense of agency. Some, especially those who received a diagnosis with a lower risk of mortality, felt empowered by seeking out information online and advice from other parents. As has been described previously of parents of children with developmental disabilities, Reference Solomon, Pistrang and Barker44 families in our study likely achieved a sense of agency by reducing their sense of uncertainty. We found here that parents’ coping strategies evolved prenatally to postnatally: parents moved from feeling helpless to more in control as the prenatal diagnoses became clearer. When parents met their child face-to-face after birth, and prognostic uncertainty diminished, their sense of and desire for control often expanded. They felt more comfortable questioning providers and actively participating in generating care plans. Providers’ communication may need to change as well, both to help parents to cope adaptively with postnatal events and to encourage more effective participation in decision making in their child’s care.

Considerations and limitations

The purpose of this study was to describe families’ experiences from prenatal diagnosis until after birth. Future studies conducted at multiple institutions with a greater diversity of families can further inform knowledge on this important topic. Most mothers interviewed in this study had already had a successful pregnancy. The experience of women who do not have prior children may be different, with distinctive coping mechanisms. Future research should investigate how these attributes affect emotional processing.

Additionally, interviewees in this study may have perceived the interviewer (KWH) as part of the medical team despite measures to mitigate this possibility, which could have influenced participant responses. Even if they understood her role as a researcher, engaging in the study interviews may have served as a coping mechanism for patients, which could itself be studied as an intervention in the future. Reference Re, Dean and Menahem45

Conclusion

This study suggests that parents’ journey following a prenatal diagnosis of CHD is psychologically complex, affected in important ways by the child’s prognosis, by the inevitable waiting, and by the child’s ultimate birth. Prior to delivery, parents typically seek to maintain hope as they work to understand their child’s diagnosis. However, their coping styles and approaches to information gathering appear to vary depending on the severity of their child’s prognosis. Expectant parents whose child has a higher risk of mortality seem to demonstrate “critical hope” by focusing on positivity and their day-to-day life as a coping mechanism. They also tend to rely more exclusively on clinician-provided information, as opposed to that found on the internet. Regardless of prognosis, parents’ sense of control often expands following delivery, leading them to seek more active engagement in clinical decision making. Understanding the trajectories of parental emotional processing and coping after prenatal diagnosis of CHD, including influencing factors like prognosis severity, may help clinicians meet families’ needs more effectively.

Table 3. Thematic analysis summary of illustrative quotes

a Participant quotes are identified first by family number (1–21), then by participant role (M = mother, F = father, O = any other support person), then by time point of interview (1–3), and finally by risk of mortality (H = higher, L = lower). Thus, 5.F.2.H indicates a quote from a father of family number 5 during the second interview with a higher risk of mortality diagnosis.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951122002505

Acknowledgements

We thank the families and physicians who voluntarily enrolled in this study to afford the opportunity to learn about the deeply personal challenges in navigating the uncertainties surrounding a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Physicians did not receive compensation; other patients did receive a gift card as described in the Methods section. We thank the staff from the Fetal Cardiology Clinic at Vanderbilt for their assistance with study logistics.

Financial support

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R38HL143619 and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002243. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.