When the painter Paul Sandby nicknamed his friend Edward Rooker’s son, and his own pupil, Michael ‘Angelo’, his jest was well founded.1 Michael Angelo Rooker became a fine artist with a particular interest in architecture and spent much of his life painting larger-than-life commissions that adorned public interiors. In 1779, aged thirty-three, he joined George Colman the Elder’s company at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, as its scene painter. Rooker thus played a major role in the 1789 production Ut Pictura Poesis, or, The Enraged Musician, the afterpiece at the centre of this chapter. In what follows, I will introduce this drama in greater detail, before focusing on four key episodes: a satire on national identity in the first scene; the ‘interruption’ of the titular musician by cannons; the scene change that first reveals Rooker’s re-creation of William Hogarth’s famous image The Enraged Musician, and then populates it with performers; and the raucous finale, which realises that image in composed and choreographed action rather than in the frozen tableaux more familiar from the nineteenth-century stage. Taken together these passages pose valuable questions about the relationship between sound and sense that still resonate in the sound box of academic discourse. Above all, their realisation of The Enraged Musician in actual sound, rather than sight, gives the lie to what many interpreters of that image have claimed on behalf of Hogarth: that the rude vitality of indigenous street music will triumph over the unmanly artifice of elite foreign culture. But before getting to grips with Ut Pictura Poesis, I would like to begin with a drawing that Rooker executed some four years earlier: a fascinating self-portrait of the artist at work in his scene-painter’s loft at the Haymarket, reproduced as Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Michael Angelo Rooker, The Scene-Painter’s Loft at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, c. 1785. Pen and ink, grey wash, and watercolour, 37.6 × 30.3 cm. British Museum, London, no. 1861,0518.1138.

This image is characteristic of Rooker’s attention to perspective, while its structure is material: beams and ladders, foregrounding the mechanics of his craft. Objects such as the dog and the two-tier stepladder appear almost as if superimposed. Most curiously, Rooker has coloured the entire image with the exception of himself and his immediate equipment, drawing attention to the artifice in play. All that is colour (allowing the dog), he – he the real, not the depicted artist – sees before him. That which is uncoloured, he sees in imagination only: artist, tools, and canvas do not in reality form part of the scene, but stand outside it, in order to bring the image into being. In a drawing concerned with exactitudes of scale and proportion, the fiction of the artist at work is conspicuously unfinished, unreal.

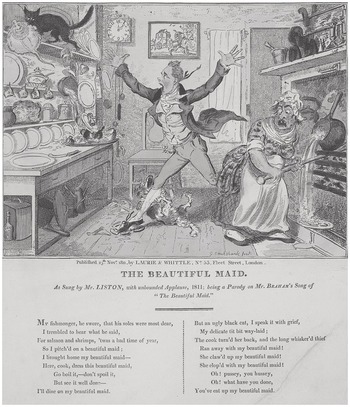

To draw attention to the levels of representation and reality at play here may seem gauche – yet it is what Rooker himself is doing in this meditation on his own role in the theatre, and in this preoccupation he was typical of the later Georgian theatre-maker or theatregoer. Venues specialised in forms of spectacle, from the horse ring at Astley’s Amphitheatre to the aquatic tank at Sadler’s Wells, where real cavalrymen re-enacted battles and children manned model ships, each striving for verisimilitude and claiming authenticity while drawing attention to their skill at conjuring and make-believe.2 Advances in stage machinery drove an obsession with mechanical effects from thunder to explosions that were increasingly associated with the emerging genre of melodrama from the turn of the century – a form that precipitated new approaches to the real.3 The theatre even produced its own paratexts that played upon the relationship between the real, its dramatic representation, and its afterlife in domestic performance, in the form of elaborate song sheets published by the firm of Laurie and Whittle. These sixpenny editions of the lyrics of the latest stage hits were headed by vivid illustrations (which could be had in colour for a shilling) that realised the action of the song. Thanks to the boundless possibilities of the page, relative to the practical and financial constraints of the stage, these illustrations – which might be passed around and pasted into albums and commonplace books, but primarily served as imaginative aids to amateur singers – could depict the song’s subject in greater and more involved detail than the original staging. Thus a song’s famous singer might be drawn amid a full-scale battle, participating in a donkey race, being carried off by a flying devil, or – in the memorable example of John Liston’s comic parody ‘The Beautiful Maid’ – chasing a cat across a devastated kitchen in pursuit of a stolen flounder (see Figure 3.2). Note in this last instance that, while the central figure is clearly Liston, who had a distinctive physiognomy, the artist George Cruikshank is able to transcend the capacities of the stage by including a real cat and perilous fire – elements no theatre manager would countenance. The illustration lacks the original’s dimensions of musical sound and live action, but it has gained an exact equivalence of reality between the singer and their surroundings, and for the domestic re-interpreter it might facilitate an imaginative, though still ludic, engagement beneath and beyond that available in the theatre. Though the example I have given is comic, the potential for sympathetic engagement with passion, patriotism, or horror is manifest.

Figure 3.2 George Cruikshank, ‘The Beautiful Maid’, 1811. Hand-coloured etching, 30.1 × 25.7 cm (sheet). British Museum, London, no. 1865,1111.2060.

Even in a theatrical culture deeply interested in its own relationship to reality, these song sheets are remarkable in their mediation between the real and the imagined, especially since they are themselves each the material and visual scripts, or blueprints, of a sung and embodied musical performance.4 As both the residue and (so long as the tune is known) the prompt for a fugitive sonic theatrical act, illustrated lyric sheets epitomise the interplay of sound and sense. In this chapter, I interrogate that interplay further by focusing not on the image of a sung performance, but on the sung performance of an image: the 1789 production of what was billed on publication as ‘Ut Pictura Poesis, or, The Enraged Musician, a Musical Entertainment Founded on Hogarth, Performed at the Theatre Royal in the Haymarket, Written by George Colman Esqr. [and] Composed by Dr. Arnold.’5

While Hogarth’s The Enraged Musician (1741), reproduced earlier in the volume as Figure 1.1, is one of the best-known artworks of the eighteenth century, a touchstone of sound studies, and the subject of entire monographs, its later staging remains obscure.6 Before examining Ut Pictura Poesis in detail I would like to draw attention to two aspects of its production. The first is its collegial nature. While The Enraged Musician, though popularised by engravers such as John June, is attributable solely to Hogarth, theatrical pieces are necessarily more collaborative, and rarely is this more demonstrable than in the present case. Although the writer, cast, composer, and orchestra all figure, it is Rooker – the highest-paid member of Colman’s company, receiving twice the salary of Samuel Arnold, the composer, and £5 a week more than his Drury Lane rival Philip James de Loutherbourg – who provides the link to Hogarth.7 Rooker’s father and mentor Edward had worked extensively with Hogarth as an early fellow supporter of the Foundling Hospital, and Michael Angelo himself shared illustrative responsibilities with Hogarth for a complete edition of the works of Henry Fielding.8 As we shall see, there is much in Rooker’s previous work that suggests his influence, as well as Colman’s and Arnold’s, in shaping the afterpiece. My point is to demonstrate that so collaborative an art form as the theatre, relying on the mixed media of text, music, design, and so on, is created as well as performed by multiple figures. In this mixed creative process the senses of hearing and sight in particular influence each other, so that writer, composer, and painter interact in the generation of meaning, rather than providing discrete parts of a composite whole – which is realised, of course, only in performance.

The second aspect is the mutually constituted discourse between Hogarth’s image and the through-composed performance: between, in other words, elements of sight and sound. In staging what was already notorious as ‘the noisiest picture in English art’ – an image that Fielding claimed was ‘enough to make a man deaf to look at’ – Colman’s company created more than light entertainment, and the ways in which the drama probes the relationship between sight and sound, music and noise, representation and reality, remain intellectually provocative.9 I am not the first to be drawn to these provocations. Martin Meisel includes a brief analysis in relation to the evolution of theatrical realisations.10 Tom Lockwood considers it as an afterlife of the work of Ben Jonson, since its plot is an explicit nod to Jonson’s Epicœne.11 Timothy Erwin’s treatment is the most extensive, in the realm of aesthetic and formal literary discourse.12 These discussions have focused less on the play itself than on the text – or rather a text, the published pamphlet containing the libretto. A forty-page reduction of the score for voice and domestic piano was also published, however, and has even been digitised by the British Library since the time of writing, and I will make use of both texts in imagining what the play’s fifteen stagings may have been like.13

Ut Pictura Poesis

Ut Pictura Poesis was a through-composed musical afterpiece in one act, and the last piece ever performed under Colman the Elder’s name. It opened on 18 May 1789, just weeks before Colman’s declining mental health necessitated his retirement. The entertainment fared better, proving the most successful afterpiece of the season and enjoying eight consecutive performances from the opening night and fifteen in total, in the last four of which it was the main item on the bill.14 The papers also deemed it a success, noting that it was ‘much applauded’: the Historical Magazine judged the music as ‘throughout pleasing and characteristic’; the Universal Magazine approved, in a nod to the Latin tag, that ‘the poet has given a very entertaining personification of the ideas of the painter’; and the critic for the European Magazine allowed that ‘the Drama has much merit as a composition’.15 Nor was this praise occasioned by partiality to a particular actor. The cast was an ensemble one, lacking any exceptional stars. John Edwin junior, the gregarious son of a celebrated comic singer, read the prologue, while Elizabeth Bannister was probably the best known of the performers, the other main female part being taken by the young Mrs Plomer, with Maria Iliff, wife of an established member of the company, making her debut in the breeches role of the lover Quaver. The much-loved singer Georgina George, in her final London season, had a cameo as a milkmaid, while the apprentice composer William Reeve enjoyed the biggest notice of his career as the knife-grinder.

The plot, lifted from Jonson’s Epicœne (a work much republished and commented upon in the later eighteenth century, and adapted by Colman himself in 1776), is as simple as most afterpiece plots.16 Castruccio, the titular musician, gives a singing lesson to his daughter Castruccina and her friend Picolina, which is interrupted by cannon celebrating a state occasion. Distressed, he sends the young women to discover what is happening. Outside his window, young Quaver convinces a milkmaid to carry a love letter to Castruccina. Next a knife-grinder, who knowingly cites Epicœne as a precedent, conspires with Quaver to throw Castruccio off guard, so as to give Castruccina an opportunity for elopement. Quaver serenades Castruccina, who agrees to marry him as soon as she can escape. Street criers assemble, enraging Castruccio; Quaver ascends a ladder to extract Castruccina; they are seen, but the mob prevents Castruccio from following, before the lovers return to taunt him as his cries are drowned by the tumult, at the height of which the curtain falls, a handwritten stage direction adding that the noise should continue ‘some little time after’.17

Already we may perceive points of interest for the themes of this present volume. When we remember the Georgian theatrical preoccupation with reality and representation, it is noteworthy that the climactic realisation of the image does not end ‘with the players freezing in position’.18 Rather, as Meisel observes, it is alive with noise, music, and movement:

Animating the picture in Colman’s theatre means giving life to the noise, noise that depends on motion, and the forms of a pictorial dramaturgy are not yet so overriding and unreasonable, not yet so attuned to the graphic visual image, as to ignore this necessity. Only the nineteenth-century theatre would be paradoxical enough, or simple enough, to try to give life and truth to such a picture by returning it to stillness and silence.19

Meisel draws attention to the dependency of noise (and music) upon motion: in giving diegetic voice to Hogarth’s image, the performers must also give life in the form of bodily movement; with lungs and limbs. As a result, the ‘picture’ cannot be returned to the state of a fixed impression but must be observed over time in order for meaning to be generated by the performance of musical sounds.

This idea of the dependency of meaning upon movement plays out across the whole afterpiece, as the plot itself suggests a sequential reading of Hogarth’s image, its successive episodes approximating to the eye’s journey from left to right across the print.20 Thus the drama opens with the musician at his work as the figure to which the eye is drawn. The first scene stages the confrontation between elite Italian music and simple native balladry that we may also read into Hogarth’s juxtaposition, at left, of the literally elevated musician with the ballad-singer beneath him. The second scene brings us first the milkmaid at the picture’s centre, and then the knife-grinder at its right, before concluding with a realisation of the whole. Given that the critic for the European Magazine judged that ‘the story as told by the painter is adhered to … the Drama has much merit as a composition’, it seems plausible that this structure was a deliberate attempt to evoke, in performance, the effect of ‘reading’ the image from left to right before coming to a comprehension of the whole.21

This sequential engagement brings us back to Rooker.22 As an illustrator of novels such as Fielding’s, Rooker was familiar with conceiving of a narrative as a series of discrete images, much as is offered by the passages of the play. Moreover, as a pupil of Sandby and a frequent depicter of street scenes himself, Rooker, like Hogarth, was steeped in the pictorial tradition of the London Cries. In a lineage stretching back through Sandby to Marcellus Laroon and to early Tudor woodcuts, the overwhelming cacophony of the London street would be divided into individual picturesque figures, each framed and annotated, creating visual order and category from what must, in reality, have been a rather intimidating confusion for respectable citizens.23 In preceding the ensemble realisation with a series of cameos for individual street criers (the milkmaid, the knife-grinder), Ut Pictura Poesis in effect reprises the genesis of Hogarth’s original image: reassembling a motley multitude in rude response to an earlier sequence of individuated figures. Again, it is tempting to trace Rooker’s hand in this homage to Hogarth’s own antecedents.

The London Cries had a musical as well as pictorial precedent. Since the sixteenth century, composers had delighted in polyphonic settings of various street cries. Though this peaked in the later Tudor period, when elite musicians including William Cobbold, Richard Dering, Michael East, Thomas Ravenscroft, Thomas Weelkes, and most famously Orlando Gibbons all indulged in this rather condescending jeu d’esprit, the practice remained constant up to and beyond 1789.24 By the later eighteenth century, much as Hogarthian commercial prints aimed at a middling audience had revolutionised the art market, so had humbler compositions in the form of catches or glees for domestic performance largely replaced the complex orchestral settings favoured by Gibbons and his peers.25 Several of these musical editions were themselves illustrated. Once more, the interplay of musical and artistic traditions informed theatrical practice.

In Ut Pictura Poesis, this sensory multiplicity extends to a dizzying meta-conversation between creators and their creations. We are invited to consider a series of sequential relationships. These begin with the real street criers, and the musical and visual traditions of their representation. This in turn leads us to Hogarth’s celebrated intervention in those traditions, and a consideration of the performed drama as an engagement with Hogarth. Here, different forms of media come into play: the published play text and score resulting from this drama; while the domestic performers of these paratexts were themselves conditioned by a familiarity with both illustrated song sheets and the ongoing corpus of ‘London Cries’ catches and glees. Ultimately, we return to the power dynamics between these different artists and performers and the real street criers, with whom the traditions began at least two centuries earlier, but who were still encountered in the streets outside the theatres and parlours where these performances were enjoyed. With this palimpsest in mind, it becomes something of a relief to follow the practice of illustrators, and turn from the jumbled whole to a consideration of discrete passages.

‘Nature must give way to Art’

Perhaps the greatest – or at least the most conspicuously reiterated – debate in eighteenth-century high culture was that of nature versus art. This dichotomy was often conflated, by no means consistently, with others, such as ancients versus moderns, and – especially in music – indigenous versus foreign. In the final case, while the latter could be German complexity or Italian ornamentation, the former was consistently native English simplicity, exemplified by the unadorned strophic ballad. This crude reduction of a vast scholarly topic is perhaps most apparent in the astonishing success of English ballad opera from the 1720s onwards – John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera is its exemplar – and it is this self-conscious celebration of rude English vitality that Hogarth enshrines in The Enraged Musician, made explicit by the inclusion, at far left, of a playbill for the original staging of The Beggar’s Opera.26

In making this an issue of national identity, both Gay and Hogarth had a precedent in Joseph Addison, who declared in 1711 that ‘There is nothing which more astonishes a Foreigner … than the Cries of London.’27 Erwin too reads The Enraged Musician as a national ‘manifesto’ that ‘promotes Britishness and British art. Much the same national difference was celebrated on the late eighteenth-century stage when George Colman the elder staged a one-act farce after upon [sic] the print.’28 In taking the exceptional and unrealistic step of giving the ballad-singer in the street below the musician’s window a copy of the famous seventeenth-century ballad ‘The Ladies’ Fall’ that contains recognisable sheet music (eighteenth-century slip songs never included musical notation), Hogarth reinforces this point, ironising the status of ‘native’ music as ‘low’ and ‘foreign’ music as ‘high’. The incongruity of observing musical notation in the street singer’s hand turns aside from the wider contrast between elite ‘musician’ and street ‘noise’ to present instead a clash of differing legitimate musical cultures.29 The ballad-singer, Hogarth implies, may be a fallen woman, but she is the most explicitly musical of the rude mechanicals in the street, and her simple, native, outdoor song endures when the artificial Italian violinist has been silenced.30 Hogarth’s judgement is clearly equivocal, as his portrait of the balladeer is far from sympathetic – yet this remains a warts-and-all victory for the crude English ballad.

In ‘reading’ Hogarth from left to right, Ut Pictura Poesis begins with a scene that re-creates this national confrontation in both its recitative and its songs. Curiously, its most obvious joke – the musician is called ‘Castruccio’ – is in danger of being missed in performance, as he is not named aloud until scene 2 (libretto, 10). While the name suggests that Colman associated the late composer Pietro Castrucci with Hogarth’s image, it also carries connotations, to an English ear, of the ‘castrato’, a figure increasingly held up as the epitome of the unnatural in eighteenth-century music by English critics. The association is reinforced when Castruccio proceeds to sing ‘Non temer bell’ idol mio’ entirely in falsetto (libretto, 5; score 9). This is followed by two contrasting recitals: Picolina, berated for introducing ‘Tricks’ and ‘Extravaganza’ into her singing (libretto, 5–6), is again criticised for her ostentatiously florid performance (score, 10–12), full of extensive melismatic passages and ornamentation – which is, for good measure, a setting of Alexander Pope’s lines:

The nineteenth-century song scholar Charles Mackay reads these lines as a satire on the Georgian taste for insincere classical allusion and pastoral cliché31 – a verdict confirmed in Ut Pictura Poesis when it is followed by Castruccina’s performance ‘in a different style’ (libretto, 6) of the far simpler ‘Alas and woe to Fanny’ (score, 12–13). This two-verse song is praised as ‘Divino!’ (libretto, 7) by Castruccio, unaware that its lyrics are at his expense, since their narrative of a daughter’s heart being stolen away despite the efforts of her ‘daddy’ is a direct foreshadowing of subsequent events.

Ostensibly, this episode is a straightforward staging of musical national identities, in which the artful Italian is bested by the simple English. Yet even at the level of text, this message is complicated: the play text criticises Picolina’s excesses, not as Italian, but (rather bizarrely) as ‘Antient British’ and ‘Welch’ (libretto, 5–6), while Castruccio is laid open to the audience’s ridicule not so much for his Otherness as for protesting too much in his attempts to assimilate. In overpraising Castruccina’s ditty as ‘the musick of the spheres!’ (libretto, 7) Castruccio risks tipping into bathos. This is underlined by his subsequent couplet, with which he prefaces his attempt at a patriotic loyal ode:

To claim to be naturalised in recitative was self-defeating, since one of the hallmarks of English ballad opera, as championed by Gay, was to substitute spoken prose for recitative, in a challenge to the perceived artifice of through-composed Italian opera. Nor was this an antiquated distinction in 1789: it is worth noting that the Haymarket company staged The Beggar’s Opera in the same season as Ut Pictura Poesis.32 Further giving the lie to his claim, the ode itself (libretto, 7) is sung in a cod-foreign dialect – substituting ‘vot’ for ‘what’ and ‘dis’ for ‘this’, and featuring an imperfect grasp of grammar – that continually undercuts Castruccio’s claim to Englishness. It appears as if Colman and Arnold are making a self-interested point here, sending up the foreign composers from Handel onwards (Castrucci, not incidentally, had been the leader of Handel’s orchestra) who had prospered in London at the perceived expense of native talent.

Yet it is when we consider the passage as performance, rather than as text, that the ironies in this argument appear. Castruccio’s falsetto aria ‘Non temer bell’ idol mio’ was excerpted from a lyric by Metastasio that had been twice performed at the Haymarket itself in the previous decade, in settings by Giovanni Paisiello and Joseph Schuster, the latter of which appears to be the basis of Arnold’s 1789 arrangement.33 An approving review noted that ‘The Italian air, “Non temer beli ido mio” [sic], (the composer of which we do not recollect) is well chosen, and in its new situation full of effect.’34 And this was the crux: to succeed as an entertainment, there was no scope for Castruccio’s aria or Picolina’s piece to be written as deliberately poor or tasteless, since every number had to please its audience. While Colman’s company might indulge in lightly nationalistic gestures and anti-Italian satire, it was in the business of performing Italian opera itself, and its audience – though it might protest otherwise – was evidently partial to Italianate music. Thus it became aesthetically as well as commercially impossible to replicate Hogarth’s total rejection of elite foreign music in a venue dedicated to its performance, an irony that blunts the edge of the satire.

One extensive review of the music epitomises this contradiction, managing both to endorse the preference for simple, native melody and to enjoy Italianate artifice – rather missing the point in the process. ‘“Flutt’ring spread your purple pinions,” sung by Mrs. Plomer, is an attractive air, and conveys the words in a characteristic style. With the following melody, “Alas, and woe to Fanny,” sung by Mrs. Bannister, we are exceedingly pleased: its native simplicity renders it powerfully impressive, it gives an example of Thomson’s remark, “Beauty, when unadorn’d, adorn’d the most.”’35 The entire episode reveals both the limitations and the possibilities of dramatising Hogarth’s visual argument. Musical difference could be performed only up to a certain point, and what is described in recitative as abominable must pass in performance as pleasurable. In bending to these very limitations, Ut Pictura Poesis becomes instead a satire on the hypocrisy of a nationalistic discourse that decries the artificial and venerates the simple while being perfectly happy, in practice, to patronise both.

‘O Damn the cannon’

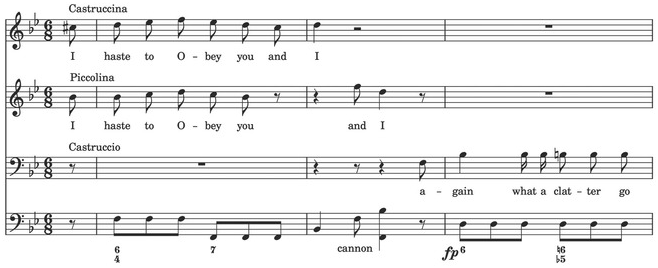

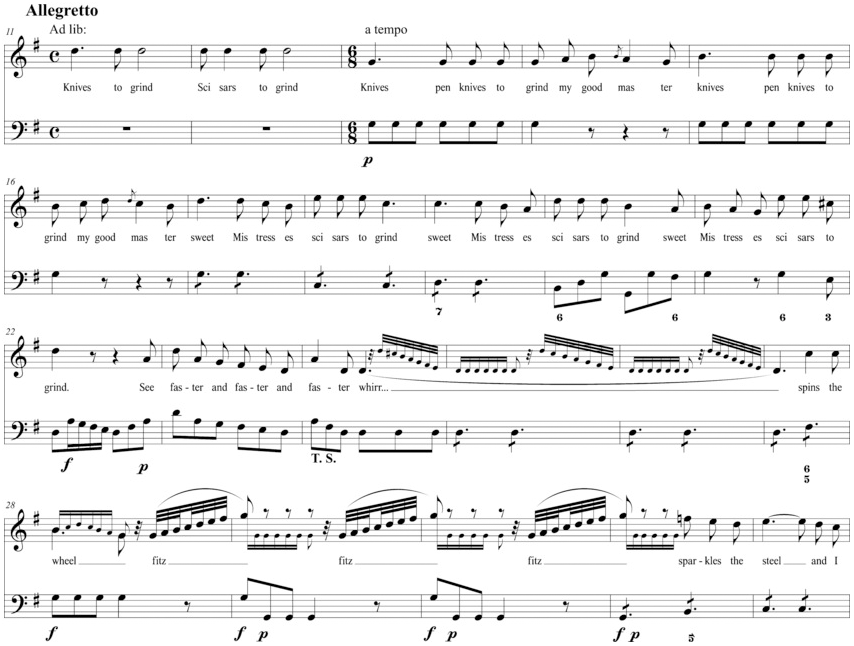

My second reading turns from this argument to an equally familiar trope of aesthetic criticism foregrounded by Hogarth: the distinction between music and noise. Castruccio is fated never to complete his loyal ode. He makes it through just eight bars of song before breaking off at the report of a cannon (score, 16), a fermata in the melody line indicating the interruption of the tune. In total gunfire occurs five times, the first three of which are shown in Example 3.1. How are we to conceive of these ‘interruptions’? Most pragmatically, could a literal cannon have been used? A later nineteenth-century inventory of the Haymarket’s props list reveals ‘two rows of five small cannon, with covers’.36 The greatest problem may have been that of timing. Military science was in the process of mastering the length of fuses, but in 1789, preceding the Napoleonic Wars, gunnery was less reliable than it would be for later battle music: for Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, penned in 1880, or even for Beethoven’s 1813 Wellingtons Sieg.37 It seems unlikely that the Haymarket was capable of firing five cannon with the precision required to detonate three beats into a bar of music. As to the risk of conflagration, such as when the Globe Theatre was engulfed in 1613 after a cannon malfunctioned, it is enough to note that a month into the run of Ut Pictura Poesis, the opera house on the other side of the road was burnt to the ground. We are faced, on balance, with the probability of a percussive noise that the audience was asked to believe to be a cannon: something representational, theatrical.

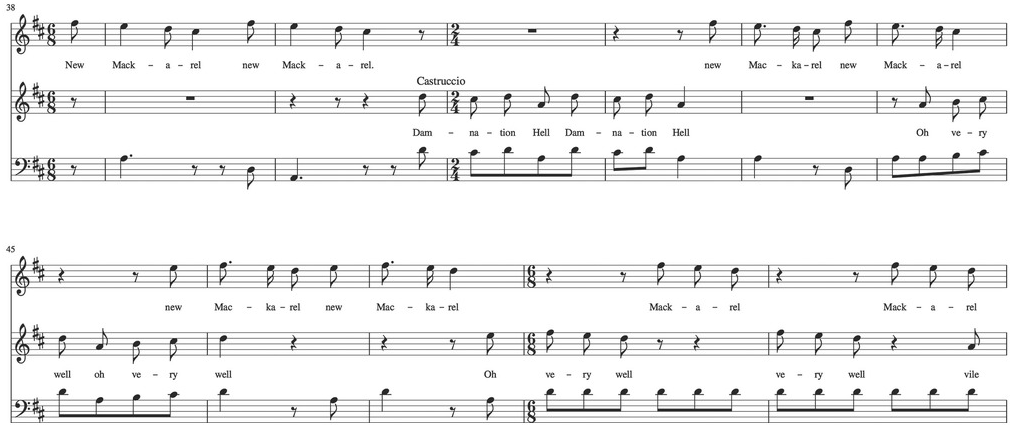

Example 3.1 Samuel Arnold and George Colman the Elder, The Enraged Musician, a Musical Entertainment Founded on Hogarth (London, 1789), 15–16, bars 18–33 of the ‘Trio’.

This speculation prompts a more searching question: was this noise musical? The limitations of the piano reduction are plain here. Can we read anything into the fact that the shots are tuned, respectively, to G, E♭, and F? In this score, the sounds have been translated to the lower register of the keyboard, which in most cases would have been either a fortepiano or a harpsichord, neither of which could sound much like a cannon. In the first four instances, the shots are on the same note in the bass as that which precedes them, simply lowered an octave. While the fermatas suggest confusion, the logic of the notes suggests instead continuation: the cannon may halt Castruccio, but it interrupts neither the composition nor (in domestic performance) the accompanist. By the fifth instance, shown in Example 3.2 (score, 18), the cannon is fully incorporated into the development of the music, harmonising with Picolina to form a B flat triad and not even putting Castruccio off his stride.

Example 3.2 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 18, bars 47–50 of the ‘Trio’.

How this reduction relates to the staged performance is unclear, but it suggests a cannon that is integral, not antithetical, to the logic of the music. This is reinforced by the lyric, where the line ‘Thames and Tweed and Shannon’ sets up, indeed requires, the ensuing rhyme ‘Oh Damn the cannon’. The cannon fire is not only musical rather than noisy, it is practically poetry – a point underlined a generation later when the construction was echoed by the author (probably the Scottish poet Allan Cunningham) of ‘On the Birthday of Princess Victoria’, published in the Metropolitan Magazine – an ode eerily like Castruccio’s, containing the couplet:

This is the first of several instances in Ut Pictura Poesis where what are described as extraneous discords, disturbing the music, are nothing of the sort, but rather necessary components of the whole, composed, choreographed, and controlled by those in charge of the entertainment. In a viable, formulaic stage production, it could not be any other way. When we speak of cannon, this musicalisation of ‘noise’ is perhaps banal, a mere anticipatory footnote to the later use of artillery as percussion in battle music. But with each reiteration, the dramatic irony takes on greater significance, especially as the drama moves towards a fuller evocation of Hogarth’s image.

‘As in Hogarth’?

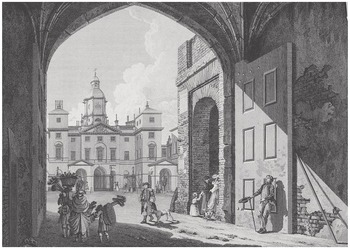

Following the meticulous ‘disorder’ of this trio, the scene ‘changes to the outside of Castruccio’s house, as in Hogarth’ (libretto, 8), an effect indebted to the artistry of Rooker, the company’s machinist as well as its scene painter.39 Was Rooker acknowledging his own debt to Hogarth, from whom he had adopted the practice of dropping beggars and street vendors into his foregrounds? The most Hogarthian of all his street scenes, a view of Horse-Guards (Figure 3.3), even includes a playbill advertising a benefit performance of As You Like It for his own father, in a direct reference to the Beggar’s Opera poster in The Enraged Musician.40 Though none of Rooker’s theatrical backdrops survive, his architectural views may give us a good impression of the effect: as was customary, Rooker would overlay such small-scale designs with a grid, the better to facilitate their scaling-up for the theatre.41

Figure 3.3 Edward Rooker after Michael Angelo Rooker, ‘The Horse-Guards’, from Six Views of London, 1768. Etching, 41.5 × 55.5 cm. British Museum, London, no. 1978,U.3601.

Rooker’s career-long insistence on both populating his cityscapes with Hogarthian figures and ‘deflating’ his paintings of classical ruins by including modern labourers and farm animals, incurring the wrath of the ‘picturesque’ advocate William Gilpin in the process, all suggests that he, as much as the ailing Colman or Arnold, may have been the instigator of Ut Pictura Poesis – a reminder not to conceive of plays as single-authored works.42 Yet far from playing to his strengths, the production of this backdrop – necessarily unpopulated, since its inhabitants were to be live actors – required Rooker to execute what was thus the least Hogarthian of all his street scenes. Nor could he exhibit his signature fidelity to perspective and proportion,43 since the stage was different in aspect ratio from Hogarth’s image (see Figure 3.4), while the addition of a balcony (libretto, 13) and the necessity of raising the window further above the area railings in order to allow clearance for a ladder (libretto, 15) entailed further deviations from Hogarth’s design. Nonetheless, Rooker’s re-creation appears to have been intended as a coup de théâtre, to judge by the scribbled marginal direction ‘drop saloon to set stage, Rise’ (libretto, 8), suggesting a secret dismantling of the indoor set to reveal Rooker’s imitation when the curtain rose. It became a test of the audience’s credentials, as well as Rooker’s, to see if they knew their Hogarth well enough to recognise a scene thus unpeopled. The critic for the Historical Magazine appears proud to have passed, recording: ‘A well-executed scene is introduced from the print, in which John Long, Pewterer [a street sign at the right of the original image], has a very conspicuous situation.’44

Figure 3.4 James Stow after George Jones, ‘Interior of the Little Theatre, Haymarket’, 1815 (detail), from a series published by Robert Wilkinson, 1825.

Before its climactic crowding, this theatrical street assumes a more generic status as backdrop for two theatrical duologues: the chance meetings of Quaver (Castruccina’s lover) with first the milkmaid, and second the knife-grinder (libretto, 10, 12). Thus the riotous finale is anticipated with rather anti-Hogarthian vignettes, in which individual street criers are unnaturally excerpted from his teeming crowd. Indeed, the first of these meetings seems something of a misstep. While the Historical Magazine approved the milkmaid’s song, the journalist stepped thoroughly out of the drama to do so: ‘Miss George, who is returned from her long tour, had a very pretty ballad.’45 By contrast, the Analytical Review demurred that ‘“Ye nymphs and sylvan gods,” sung by Miss George, does not, in its melody, strike us as of equal merit with some others in the piece.’46 The critic perhaps felt that the song’s affected pastoral idiom (score, 26–27), while thematically appropriate for the milkmaid, was just the sort of artificial gesture that Pope’s ‘Flutt’ring spread thy purple pinions’, performed in the previous scene, was designed to mock.

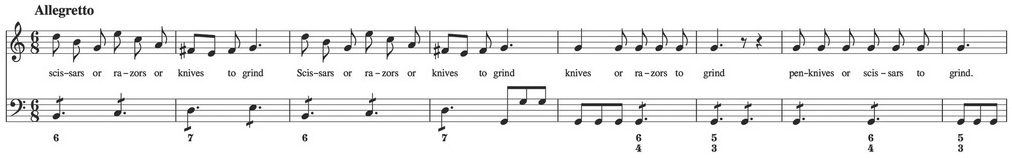

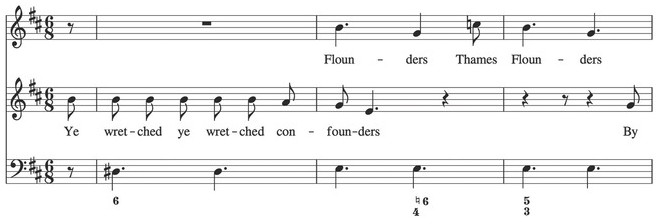

William Reeve’s number as the knife-grinder, however, ‘was much applauded’.47 The song (Example 3.3; score, 28–29) returns us to the relationship between music and noise, with the street cry holding the same conceptual status as the cannon for many in the audience – or even ranking a little lower, being devoid of a ceremonial or martial connotation. That cry begins on one note, the dominant, but swiftly shifts to the tonic, gaining rhythm, before breaking into melody, modulating from G to D major, and assuming all the characteristics of song. The abrasive sound of the grinding wheel itself, included by Hogarth as perhaps the harshest noise in the whole image, is here made musical, played by an instrument of art rather than one of labour, as it ‘whirrs’ and ‘fitzes’. The review of this published music conceded that ‘the attempt in the accompaniment, at the expression of the noise of the wheel, is more successful than we could have expected’. Yet this musicality does not last (Example 3.4; score, 29), the grinder’s distinctive melodic phrasing collapsing once again to the tonic, having been granted a temporary elevation to the aesthetic for only as long as the composer saw fit. Following on from the composed musical logic of the cannon, we are gaining a sense that, far from celebrating the defeat of elite music by street noise, Arnold’s score in fact achieves the opposite.

Example 3.3 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 28–29, bars 11–32 of ‘Knives to Grind’.

Example 3.4 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 29, bars 39–46 of ‘Knives to Grind’.

‘To discord you turn all my notes’

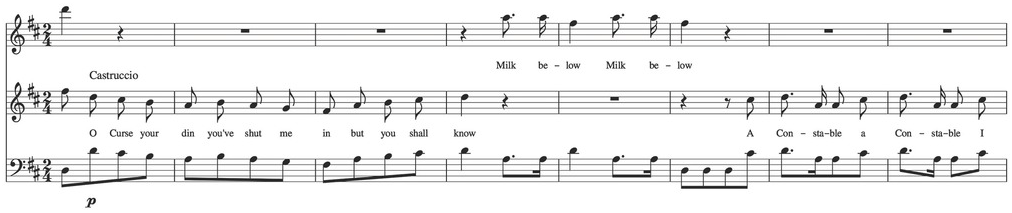

This almost alchemical compositional command over the noises of the street, which to my mind prefigures the animation of household objects in Goethe’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1797), culminates in the production’s finale. Initially, we are given a clear distinction between music and noise: the street figures are directed as uttering ‘Cries, without Musick,’ (libretto, 14) contrasted with Castruccio’s protestation in sung recitative (score, 36):

The division is starker, in fact, than in Hogarth: according to the stage directions there is neither oboist nor ballad-singer among the crowd to challenge our ideas of what constitutes the musical. Nor is this perception of a musical Hogarthian street entirely an anachronism: John Ireland observed in his Hogarth Illustrated of 1793 that the image contains treble, tenor, and bass, which ‘must form a concert, though not quite so harmonious, yet nearly as loud, as those which have been graced with the royal presence in Westminster Abbey’.48 Ireland’s wry comparison models what follows in the play: for once Quaver and Castruccina have escaped amid this expressly unmusical din, the chaos gains compositional sense and becomes a generically recognisable glee.

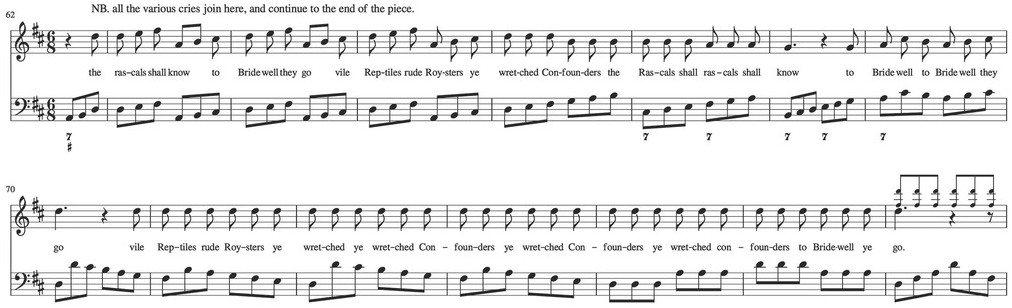

If we may trust to the reduction of the score, there are at least four stages of this glee that advance the reversal of what begins as music and noise. In Example 3.5 (score, 37) Castruccio is interrupted by the milkmaid, whose cry of ‘milk below’, though in the same key, alters the rhythm. Castruccio’s response of ‘A constable’ adopts the rhythm that the milkmaid has introduced, and one level of difference is thereby eroded, with the musician influenced by the crier – echoed lyrically by the interdependence of the two in creating the rhyme of ‘know’ and ‘below’. Castruccio falls further in Example 3.6 (score, 38–39), where in a triple exchange with the crier of ‘new Mackarel’ he moves from the defiant ‘Damnation Hell’ to the helpless ‘oh very well’. In the course of this defeat, his vocal line shifts from a strong contrast with the ‘Mackarel’ melody, to close engagement, finally capitulating to the extent that his ‘very well’ becomes indistinguishable from the insistent descending quavers, F♯–E–D, of ‘Mackarel’, the two running together in a Figaroesque double repetition. Castruccio is suffering a worse fate than discord: he is losing his voice to the street concert hypothesised by John Ireland, and Example 3.7 (score, 39) is the logical consequence. Rather than ‘confounders’ simply rhyming with ‘flounders’, the two are concurrent, with the longer ‘flounders’, pitched a third higher and thus, conventionally, forming the melody line to which Castruccio can merely supply the harmony, subsuming Castruccio’s impotent protestation and proceeding, by means of sing-song rhythm and intrusive C♮, to wrest musical control from the enraged musician. In the face of such eloquence, Castruccio relinquishes melody altogether, a total loss of identity and status shown in Example 3.8 (score, 39–40). This musical narrowing, from phrase to scale to dogged repetition of the tonic, is hardly uncommon among the codas of finales, yet it seems fair to say that the generic device takes on fresh potency in this context. Castruccio is totally defeated by the sounds of the street – but music is not: not only do the cries gain in legible musicality, but the stage directions provide for the late arrival of recognisable instruments of a sort in ‘the drums and marrow-bones and cleavers … drums playing, &c. a girl, with a rattle, little boy with a penny trumpet, old bagpiper, &c. as near as possible to Hogarth’s Print’ (libretto, 17). One reviewer described this coup de théâtre not as pandemonium but as a ‘serenade … which completes the climax of Castruccio’s rage’ – a phrase implying that the street musicians usurp the articulation of musical and gestural meaning from the titular character.49

Example 3.5 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 28–37, bars 5–12of the finale.

Example 3.6 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 38–39, bars 38–49 of the finale.

Example 3.7 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 39, bars 53–56 of the finale.

Example 3.8 Arnold and Colman, The Enraged Musician (1789), 39–40, bars 62–76 of the finale.

These late arrivals are brought on by Quaver, who has coordinated the whole affair: that is, the character whose name literally represents music is demonstrably responsible for the conducting of this performance. In kneeling front and centre (libretto, 17), Quaver and Castruccina deliberately disrupt the faithfulness of the realisation, insisting upon the addition of legible music to Hogarth’s original. Perhaps doubly legible, for if ‘Quaver’ stands for notation and thereby elite music, so might the image of united lovers stand for ‘harmony’ – a subtle visual pun entirely in accord with contemporary standards of wit. There is probably an additional allusion here: to the Spectator. Addison’s 1711 article on the London Cries, mentioned above, includes an extensive and satirical letter purporting to be written by one ‘Ralph Crotchett’, in which the said Crotchett outlines his absurd plans for regulating the cries into a harmonious musical system, offering himself as a ‘Comptroller-General of the London Cries’.50 In Addison, as in Hogarth, the idea of imposing musical order on the street is exposed as absurd. Yet in Ut Pictura Poesis, Quaver – an updating of Crotchett who might even be seen as Arnold’s on-stage avatar – is shown to be entirely successful in orchestrating just such a scheme.

Interpretations

To venture such a reading on what might be purely technical grounds seems to go against the spirit of the play. Yet it is founded upon the Georgian fascination with levels of reality and representation with which we began. In Hogarth’s Enraged Musician we see, and imagine we hear, street criers. For all the image’s layers of metatextual coding and visual wit, we believe that the milkmaid – though she may also represent the urban pastoral, compromised innocence, a reference to Marcellus Laroon – is nonetheless a milkmaid. Yet in the play, she is Miss George, just as the various criers are Mr Mathews, Mrs Edwin, et al. (libretto, 1). Just as a mock sea battle at Sadler’s Wells was in some respects less ‘real’ than a representation of the same thing on a Laurie and Whittle song sheet, so Ut Pictura Poesis, despite adding movement and sound to Hogarth’s picture, remained less real, a verdict reflected in the reviewers’ conventional insistence on praising named actors for their individual turns, rather than buying into the conceit. In such a context, the musical triumph was not that of the street over the elite composer, but that of Samuel Arnold, DPhil Oxon, governor of the Royal Society of Musicians, organist to the Chapel Royal and conductor of the Academy of Ancient Music, with the aid of the ‘excellent band’ in the pit acknowledged in the entertainment’s prologue (libretto, 3).

Having gone this far, I – as a social historian – am tempted further. Since both image and afterpiece raise issues of status, class, and labour, we might critique the staging in the same terms, and read the company’s musical triumph as won at the expense of the real, disenfranchised street criers outside the theatre. Far from shouting down the elite music taking place within, street criers had their cries – designed to attract custom for their labour and thereby to accrue capital at the rate of maybe a shilling a day – assimilated instead into that interior elite music, for the entertainment of a middling to elite audience paying between one and five shillings for the pleasure, this capital being accrued by the well-to-do company of the Haymarket. The cultural appropriation going on here (if we can call it that) serves an aesthetic as well as an economic function, however. For just as the need to give pleasure to an opera-loving audience undermines Hogarth’s criticism of Italian music in the first scene, so that same need to give pleasure undermines Hogarth’s assumed defence of the rude indigenous music of the street. The real irony is that London’s cultivated audiences far more closely resembled Castruccio than they did the gleefully demotic Quaver, and had the company served up an afterpiece of genuinely discordant London Cries, rather than a refined arrangement thereof preceded by some pleasant arias, that audience would itself have been enraged. While this consideration exposes the hypocrisy of the theatregoers, we might temper this with a reflection that, for all their vaunted musical nationalism, these Londoners were rather more cosmopolitan in their tastes than they would have liked to admit.

The result is therefore a total inversion of Hogarth’s ostensible argument: from the musical imitation of the knife-grinder’s wheel to the overarching conceit, low commerce and mechanical labour are transformed into elite art; the disorderly world of the street tamed by the choreography of the indoor theatre; and reality sacrificed to representation. By this reading the conceit starts to resemble less Jonson’s Epicœne than Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1607). In what may be more than coincidence, Rooker himself had illustrated a recent edition of that play, choosing for the frontispiece the celebrated opening scene in which a grocer and his wife interrupt ‘the play’, insisting that their apprentice be allowed to perform the part of Grocer-Errant.51 In reality – as the audience knows full well – all concerned are actors in the company, and the interruption is fully scripted. Thus what pretends at subversion is elevated drama, swiftly assimilated into the literary canon.

Mention of the canon (a concept so familiar that I have seen scholars use its single ‘n’ when referring to the sort of guns that resound so tamely in the trio of Ut Pictura Poesis) brings me to my final reflection. I offer my methodology in this chapter – a round-the-houses chase after allusions and metatextual interplay, in and out of art, literary, musical, and theatrical criticism – as an attempt to grapple with the collegial, multi-authored, multi-sensory entanglements of late Georgian culture, a world in which works, careers, and modes of audience engagement were always essentially collaborative and miscellaneous.52 Yet if my interest is in how the visual and the sonic, music and noise, and different members of a theatrical company combined to form a rich cultural discourse, is it not also the case that I have chosen to discuss this afterpiece – and that this afterpiece was only conceived – because of its relation to an acknowledged masterwork by a canonical artist? In playing in the space that landmark works create for discourse, are we snubbing the great artist at his window, or ensuring that he remains there – a little out of countenance, perhaps, but still elevated, and far from enraged?