There is an international crisis in acute mental healthcare.1 In the USA, the number of emergency department visits for patients with mental health issues increased by a third between 2006 and 2015,Reference Nam, Lee and Kim2 resulting in long waiting times.Reference Nicks and Manthey3 A similar picture has emerged in Canada,Reference Fleury, Grenier, Farand and Ferland4 the UK5 and Australia.6 Although a decrease in emergency department presentations was initially reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers have since risen again.Reference Sampson, Wright, Dove and Mukadam7,Reference Jeffery, D'Onofrio, Paek, Platts-Mills, Soares and Hoppe8 This is despite broad consensus that the emergency department is an unsuitable, non-therapeutic environment for people experiencing a crisis in their mental health.Reference Broadbent, Moxham and Dwyer9 Furthermore, in Europe, the number of in-patient psychiatric beds has decreased.10 This adds to pressure for beds and changes the ward environment; typically, levels of distress are higher in those admitted, with the effectiveness of in-patient stays for different patient groups at different levels of distress becoming a topic of serious debate.Reference Glick, Sharfstein and Schwartz11 People attending the emergency department in crisis and/or admitted for short in-patient stays often experience intense distress, feel suicidal or have attempted suicide.Reference Owens, Fingar, Heslin, Mutter and Booth12–Reference Bowers14 Therefore, there is a need for an appropriate environment to support and assess individuals who feel suicidal. In addition, in-patient admissions can be expensive,Reference McCrone, Johnson, Nolan, Pilling, Sandor and Hoult15 cause harmReference Thibaut, Dewa, Ramtale, D'Lima, Adam and Ashrafian16 and, it has been suggested, are avoidable for about 17% of individuals.Reference Stulz, Nevely, Hilpert, Bielinski, Spisla and Maeck17 Evidence for the benefits of shorter stays on in-patient wards is inconclusive,Reference Clibbens, Harrop and Blackett18 whereas efforts are increasingly being made to improve patient flow in acute and emergency mental health services.Reference Bost, Crilly and Wallen19,Reference Dawoodbhoy, Delaney, Cecula, Jiakun, Peacock and Tan20

Within this context, short-stay crisis units for people in mental health crisis have been developed and introduced.Reference Zeller, Calma and Stone21 Variously named emergency psychiatry assessment, treatment and healing units (EmPATH units),Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 behavioural assessment units,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 psychiatric observation unitsReference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 and psychiatric decision units,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 among others, these units are hospital based; allow overnight stays for a short, time-limited period; provide an appropriate environment for stabilisation, assessment and onward referral; and typically aim to reduce emergency department mental health presentations and wait times, and/or psychiatric admissions. An existing systematic reviewReference Johnson, Gilburt, Lloyd-Evans, Osborn, Boardman and Leese26 considered a range of residential alternatives to acute psychiatric admission focusing on crisis hostels, family placements and other forms of community residential services, but did not report on the types of units we consider here. The present review is the first review to focus solely on the effectiveness of hospital-based, short stay crisis units designed to reduce in-patient admissions, emergency department presentations and/or emergency department wait time.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of quantitative studies of hospital-based mental health crisis units, as described above. The protocol was preregistered on the PROSPERO website (registration number CRD42019151043).Reference Lomani and Anderson27 All outcomes with a comparison group were included. The research team was comprised of researchers who bring lived experience of mental distress and using mental health services to their roles, ensuring that experiential knowledge informed the review process,Reference Gillard, Simons, Turner, Lucock and Edwards28 as well as clinicians and academics. All aspects of the review were co-produced between individuals working from these different perspectives.

Search strategy

The search followed the PRISMA guidelines.Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Bouttron, Hoffmann and Mulrow29 We searched EMBASE, Medline, CINAHL and PsycINFO databases, using keywords and subject headings from inception to 1 March 2021, supplemented with backward reference searching and forward citation tracking of included studies. We revised our plan to include the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials because of the study types most commonly performed within this area. We included quantitative studies incorporating any comparison (no intervention, a different intervention or within-group comparison) covering a range of designs (single-, double- or triple-blind trials, interrupted time series, quasi-experimental, observational, before-and-after and retrospective studies). Entirely qualitative studies or studies with no comparator were excluded. We did not restrict the search by language. Exemplar papers in the published literature,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23–Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 non-peer reviewed reports and the broad academic, clinical and lived experience of our team were used to coproduce eligibility criteria and search terms. Because of the variability in terminology for the units, we used truncated and adjacent search terms to enhance our search (e.g. (asses* or evaluat* or stabilis* or stabiliz* or crisis or crises or observation*) adj4 (unit or units or facilit* or ward* or room* or suite* or service*)). Full search strategies are available (see Supplementary Fig. 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.534).

Eligibility criteria

Short-stay crisis units were defined as any mental health assessment service that is (a) hospital-based; (b) allows overnight stay; (c) specifies a short (less than 1 week) length of stay (LOS) and (d) primarily aims to assess and/or stabilise, with the purpose of reducing the need or LOS of standard acute psychiatric admission, and/or reducing mental health presentation or length of wait at the emergency department. Exclusion criteria were non-residential, or community- or non-hospital residential-based assessment or crisis units, and units in which the population were all detained under mental health legislation, all were forensic patients, all had substance misuse issues or were under 18 years of age.

Study selection

Following de-duplication, title and abstract screening was conducted by two reviewers (K.A. and J.L.), using CADIMA, an online evidence synthesis tool (Julius Kühn-Institut, Quedlinburg, Germany; https://www.cadima.info/index.php/area/evidenceSynthesisDatabase).Reference Kohl, McIntosh, Unger, Haddaway, Kecke and Schiemann30 Initially, 20% of titles and abstracts were screened independently and the remaining titles and abstracts screened once the inter-rater reliability score was substantial (0.61−0.80). Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consultation with a wider team (L.P.G., J.A.S. and S.G.). Full-text screening was conducted independently by two reviewers (K.A. and J.L.), and disagreements were resolved with the same method.

Data extraction and risk of bias

A standardised, pre-piloted form in Microsoft Excel for Windows (Microsoft Office 2019) was used to collate data about the intervention, comparison group, study design, sample size, country, demographics and outcomes for quality assessment and evidence synthesis. All outcome data with a comparison group were extracted as presented in the paper, making the unit of analysis clear. Data about both the total number of events and the number of participants experiencing an event were extracted. Two reviewers (K.A. and L.P.G.) extracted these data and resolved discrepancies through discussion, using consultation with wider team where necessary. The same two reviewers independently rated, for each extracted outcome, the seven categories of potential sources of bias for non-randomised studies in the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) and the five categories of the Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials (RoB 2)Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Bouttron31 for randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between reviewers, and the wider team if necessary. Each meta-analysis was then rated for the certainty of the evidence, using Cochrane's Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework.Reference Schünemann, Higgins, Vist, Glasziou, Akl, Skoetz, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch32 Certainty of the evidence was discussed for all reported outcomes, and noted in the paper where we considered the certainty to be very low (i.e. where the true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).

Data analysis

Results were synthesised by meta-analysis in Review Manager 5.4.1 for Windows (Cochrane Collaboration; https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software/revman/revman-5-download),33 supplemented by narrative synthesis where necessary. Where two or more studies reported outcomes suitable for pooling, meta-analyses were performed with random effects and 95% confidence intervals. Standardised mean difference models were used for continuous outcomes measured on a range of scales, and mean difference models were used for outcomes with a common scale (e.g. emergency department LOS measured in minutes). For events data reported per person, we used random effects relative risk (risk ratio) models with 95% confidence intervals where events were rare, and random effects odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals where events were relatively common (e.g. in-patient admissions), to make the association clearer.Reference Ranganathan, Aggarwal and Pramesh34 Analyses including studies assessed as at low or critical risk of bias were repeated in a sensitivity analysis excluding these studies, to check the sensitivity of the result to that study. Only unadjusted data were included in our meta-analyses. We assessed heterogeneity with the I 2 statistic. Publication bias was to be checked with a funnel plot and the Egger test with Harbord modificationReference Harbord, Harris and Sterne35 in the case of categorical outcomes where there were at least ten studies in a meta-analysis (with fewer studies, the power of the test is too low).Reference Higgins and Thomas36

Results

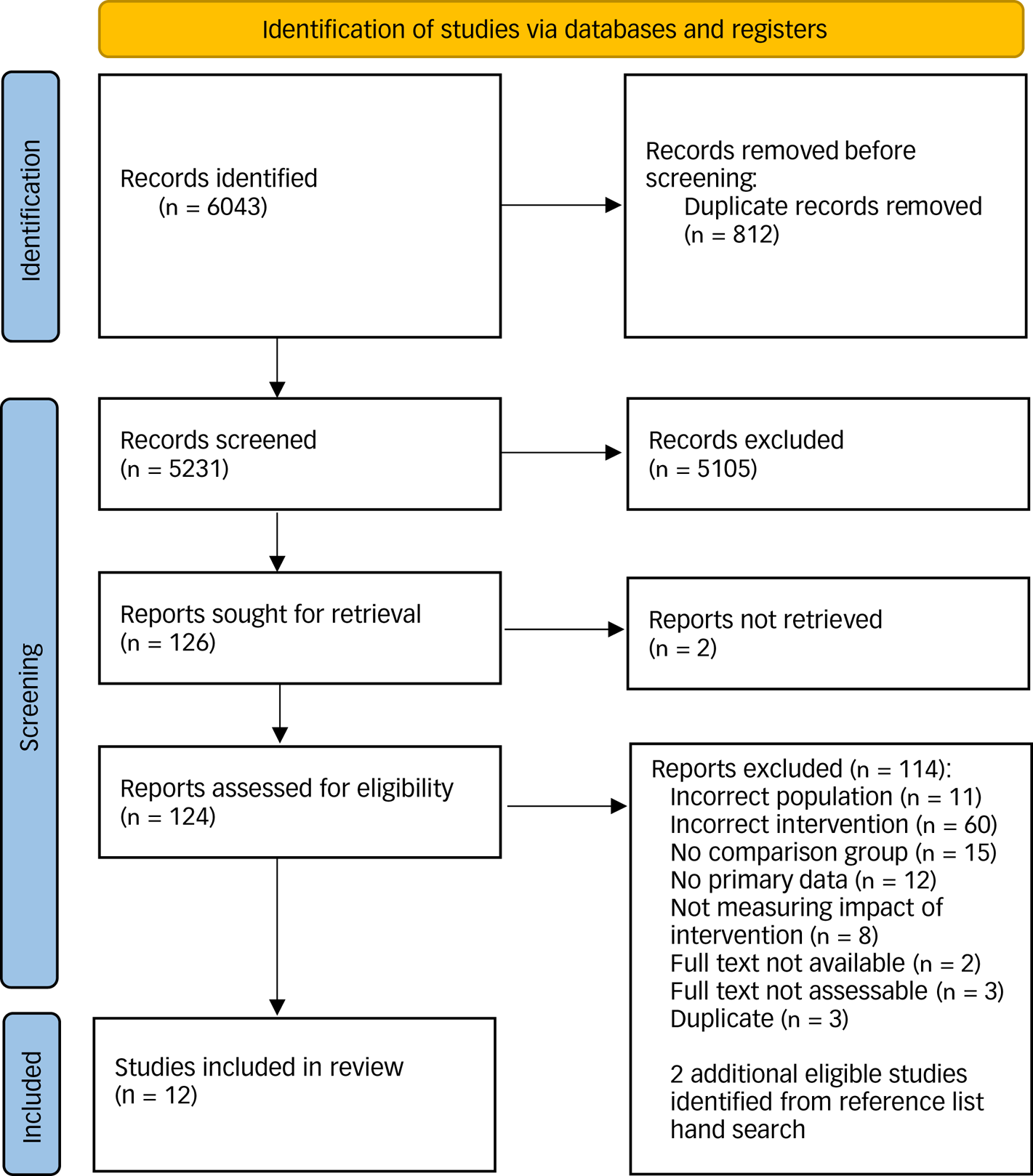

The search identified 6043 unique records, of which 124 were full-text screened and 12 met inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Of the 12 included studies, five were from the USA,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37–Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39 three were from AustraliaReference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 one was from The Netherlands,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 Belgium,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 one was from the UKReference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 and one was from Canada.Reference Mok and Walker44 Methods included nine pre–post studies,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37–Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41,Reference Mok and Walker44 one interrupted time series,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 one case–control studyReference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 and one RCT,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 all written in English. Seven studies took emergency department patients as their population;Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39–Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 in four studies, the population comprised patients referred or admitted to the unit.Reference Schneider and Ross38,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42–Reference Mok and Walker44 In one study, the population comprised people presenting via a mobile team (street triage).Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 Across the studies, 67 505 participants were included (see Table 1).

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

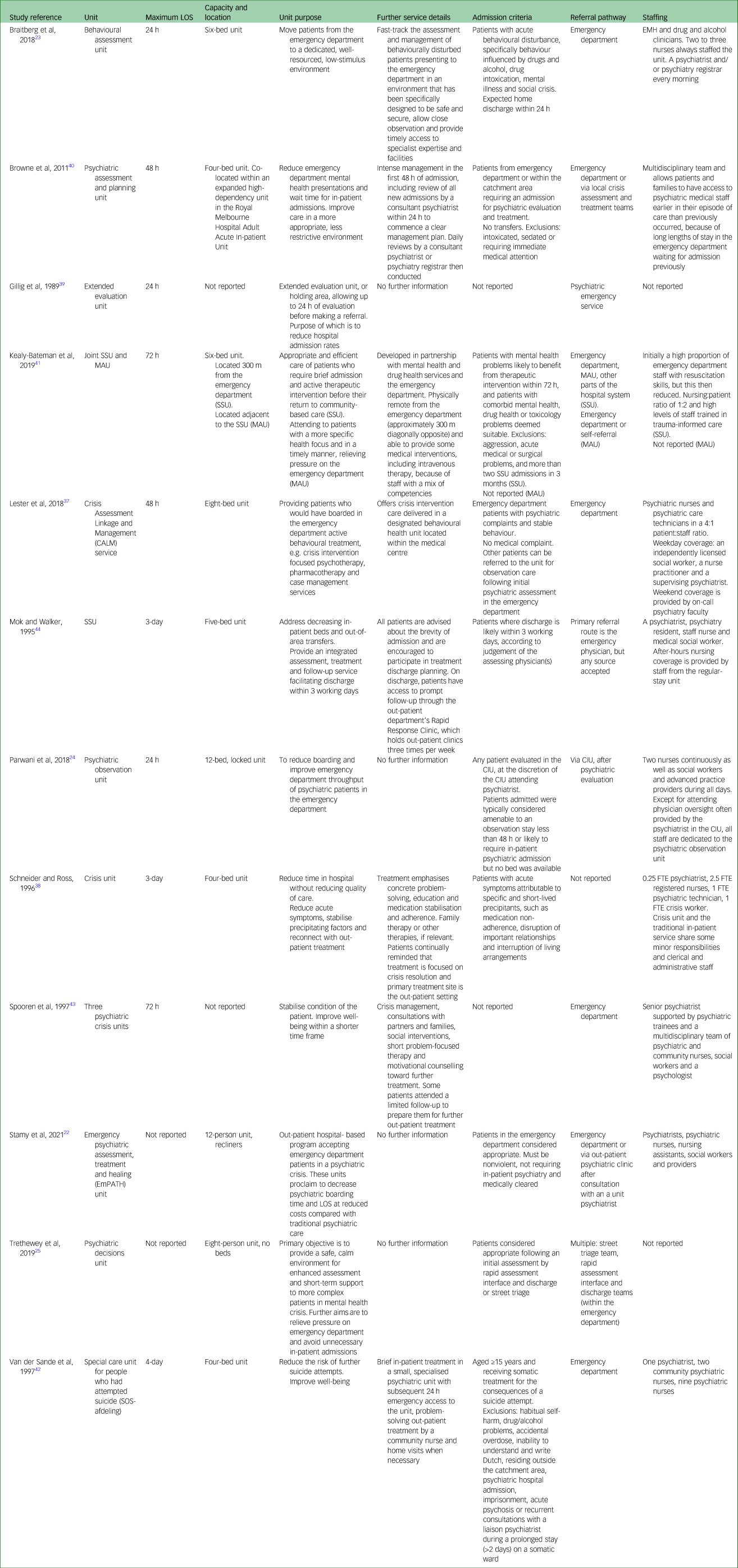

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

LOS, length of stay.

Unit characteristics

Units could be designed to address multiple purposes. Five units were designed to reduce pressure on emergency department,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 four units were designed to provide a more therapeutic environment than the emergency department,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 three units were designed to reduce psychiatric admissions,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39,Reference Mok and Walker44 three units were designed to reduce time spent in hospitalReference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Schneider and Ross38,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 and three units were designed to stabilise or improve patient well-being.Reference Schneider and Ross38,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 Further purposes unique to a unit included to reduce the risk of future suicide attempts,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 reconnect with out-patient treatment,Reference Schneider and Ross38 reduce out-of-area transfersReference Mok and Walker44 and offer crisis-focused psychotherapy and case management servicesReference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 (see Table 2). Admission criteria were variable. Four units accepted patients likely to benefit from a short admission,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41,Reference Mok and Walker44 and two units accepted people under the influence of drugs or alcohol.Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 Units also specified acute behavioural disturbance,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 acute symptoms in relation to specific and short-term stressors,Reference Schneider and Ross38 stable behaviour,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 requiring in-patient admission where there was no available bedReference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 or receiving medical treatment for a suicide attempt.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 Patients were excluded from admission if they were under the influence of or dependent on drugs or alcohol,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 displayed aggressive behaviour,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 had medical issues,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 resided outside of the catchment area,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 had a pattern of self-harmingReference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 or required an in-patient admission.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42

Table 2 Characteristics of units evaluated in included studies

LOS, length of stay; EMH, emergency mental health services; SSU, short-stay unit; MAU, Missenden assessment unit; CIU, crisis intervention unit; FTE, full-time equivalent.

Units received referrals from the emergency department,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40–Reference Mok and Walker44 the psychiatric emergency service,Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39 other assessment and intervention units,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41,Reference Mok and Walker44 out-patient clinics,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Mok and Walker44 other crisis servicesReference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 and other parts of the hospital.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 The units were most commonly staffed by psychiatrists,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Schneider and Ross38,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42–Reference Mok and Walker44 followed by social workers,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43,Reference Mok and Walker44 nurses,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Schneider and Ross38,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41,Reference Mok and Walker44 psychiatric nurses,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 psychiatric technicians or nursing assistants,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Schneider and Ross38 psychologistsReference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 and drug and alcohol clinicians.Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 Some units described themselves as hosting a multidisciplinary teamReference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 or having a high staff/patient ratio, with high numbers of staff with knowledge of trauma-informed care.Reference Mok and Walker44

Quality ratings

We extracted 41 outcomes from 11 non-randomised studies, and four outcomes from a single RCT. For the non-randomised studies, we assessed the majority of outcomes to have a moderate risk of bias (27 out of 41; see Supplementary Fig. 2). Risk of bias was typically limited because of strong study designs, which restricted both potential bias from confounding and potential bias from selection of participants. Potential bias in selection of reported result was the most common source of bias (in the absence of published protocols for most studies, it was unclear whether the full range of outcomes assessed had been reported). Three outcomes from two studies were at serious risk of bias from confounding, as there was reason to believe that the comparison and intervention groups were too dissimilar. Three further outcomes were at critical risk of bias from additional biases identified, or critical risk of bias from confounding. Seven outcomes from one studyReference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 were assessed as having a low risk of bias. In the single RCT,Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 potential bias in the randomisation process caused some concerns for two outcomes, and bias from missing outcome data caused two further outcomes to be of high concern for risk of bias (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The GRADE ratings are presented with the meta-analyses.

Synthesis of outcomes

Emergency department waiting time

Three studies reported reductions in measures of waiting time in the emergency department. The first reported that the wait to be seen by a clinician in the emergency department was significantly reduced from a median of 68 min (interquartile range (IQR) = 24–130) in the control group to 40 min (IQR = 17–86) in the experimental group (P < 0.001).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 The same study also reported a significant median reduction in the wait time for a mental health review, from 139 (IQR = 57–262) to 117 (IQR = 49–224) min following the introduction of the crisis unit (P = 0.001).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 A further study reported that psychiatric boarding, the time waiting in the emergency department for a bed or transfer, was decreased from a median 212 (IQR = 119–536) to 152 (IQR = 86–307) min (mean difference 189 min, 95% CI 50–228 min).Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 A third study reported a reduction in long waits in the emergency department. In the pre-period (between March 2006 and September 2006), there were at least 12 patients per month who waited in the emergency department for at least 24 h. In the post-period (January 2007 to January 2008), there were only six 24 h waits in the entire period (five of which were in the first month), and in the following 4 years only two patients waited in the emergency department for longer than 24 h.Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40

Total LOS in the emergency department

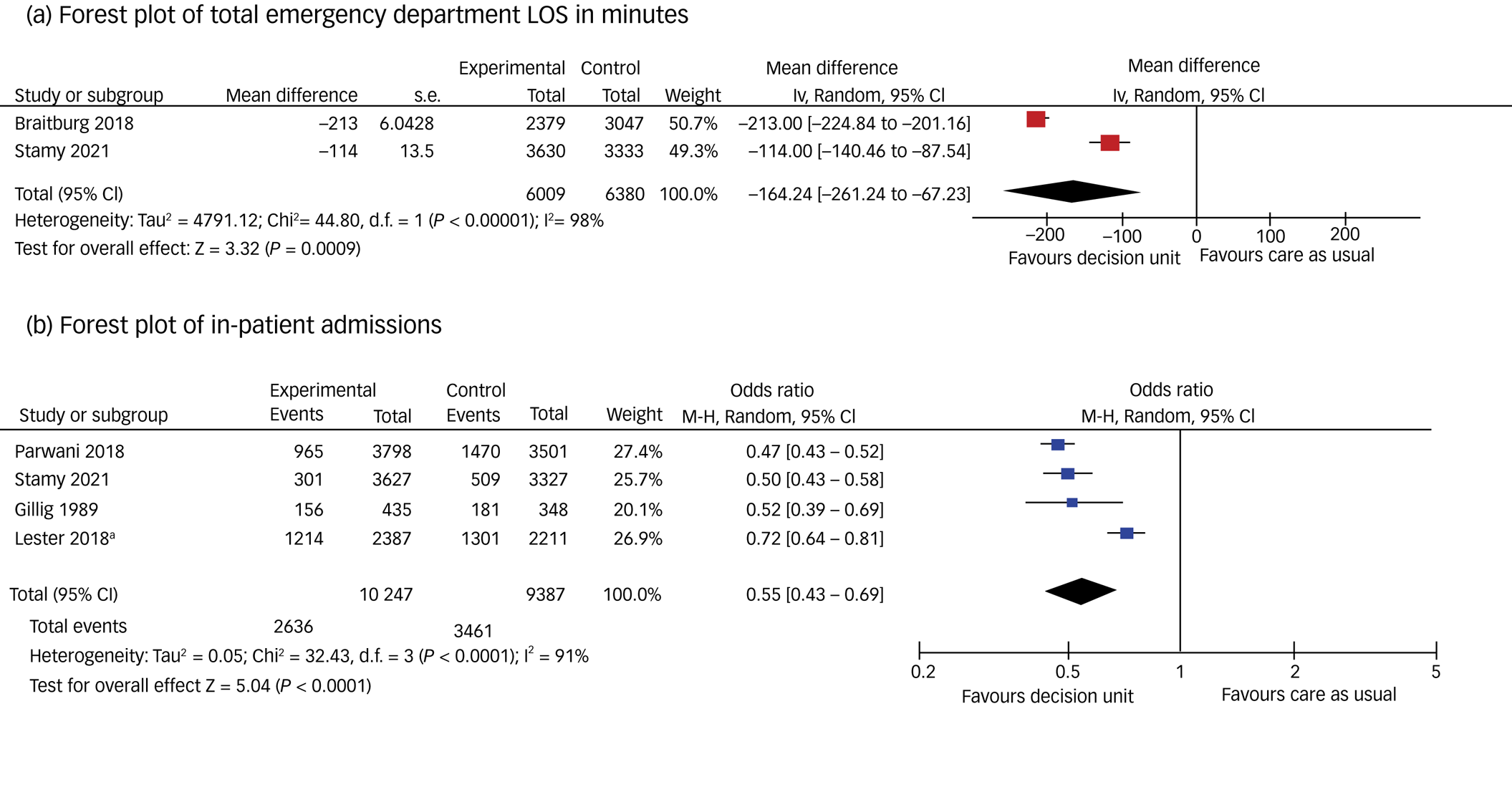

A significant reduction in emergency department LOS was found by all four studies reporting this outcome.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 One study found a mean decrease from 14.48 to 11.11 h (significant P < 0.001) in a mixed-model analysis that used log-transformed emergency department LOS.Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 Another study found a highly significant (P < 0.0001) change in the median emergency department LOS, from 155 (IQR = 19–346) to 35 (IQR = 9–209) min.Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 Another study found a reduction in mean emergency department LOS from 423 (s.d. 265) min pre-intervention to 210 (s.d. 179) min post-intervention. Expressed as medians, this is a reduction from 328 (IQR = 227–534) to 180 (IQR = 101–237) min (P < 0.001).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 Another study found a significant reduction in median emergency department LOS from 351 (IQR = 204–631) to 334 (IQR = 212–517) min in the post-period, also expressed as a reduction in the mean of 114 min, with a 95% CI of 87–143 min.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 Data for the emergency department LOS were combined meta-analytically, using mean difference random-effects models (see Fig. 2(a)). The pooled estimate for change in total emergency department LOS is −164.24 min (95% CI −261.24 to −67.23 min; P < 0.001). Data from two studies could not be combined meta-analytically as one did not report a measure of varianceReference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 and another only reported medians.Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 The I 2 is 98%, indicating high heterogeneity. The GRADE system assigns a starting rating of ‘Low certainty, confidence or quality’ to outcomes for meta-analyses of non-randomised studies. This was upgraded to ‘moderate certainty’ because of the ROBINS-I ratings, meaning that the authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect.

Fig. 2 Forest plots for each meta-analysis. (a) Total emergency department LOS in minutes (decision unit vs care as usual), (b) in-patient admissions (decision unit vs care as usual). a. Admit + transfer. IV, inverse variance; LOS, length of stay; M–H, Mantel Haenszel.

Leaving the emergency department early

One studyReference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 reported no significant difference to the number of patients leaving emergency department without being seen, which was 2.4% of patients (n = 81) in the pre-period, and 2.2% (n = 79) in the post-period; a difference in proportions of −0.3 (95% CI −1.0 to 0.5). This study also reported no difference to the combined number of patients leaving against medical advice or eloped (meaning absconded or departed without authorisation). These were 2.4% (n = 81) in the pre-period and 2.0% (n = 74) in the post-period; a difference in proportions of −0.4 (95% CI −1.1 to 0.3).Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22

Patient routes into emergency departments and wards

A UK studyReference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 reported the number of patients who were brought to the emergency department via street triage (a mobile mental health service that works with the police, particularly on weekend evenings, to appropriately triage people displaying mental health problems away from the criminal justice system) in the pre- and post-periods. The number of patients brought to the emergency department via street triage reduced from 297 in the pre-period to 180 in the post-period (presumably as some patients were diverted to the crisis unit), but the authors did not test for significance. This study found that the number of patients admitted to a ward via liaison psychiatry reduced from 298 to 219 in the post-period, but did not test for significance.Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25 A further study assessed a crisis unit that allowed stays of up to 3 days at a site that already had a short-stay unit facilitating stays of up to 48 h.Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 They report that 60% of patients admitted to the 3-day unit were admitted via emergency department, in contrast to the 48 h unit, for which almost all patients enter via emergency departments. The study was assessed as being at critical risk of bias, as it was unclear whether patients included in the control group would be equally eligible for the intervention group and vice versa.Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41

The emergency department environment

Two studies reported changes in the use of security services and restraint procedures in the emergency department setting.Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 Code grey events are formal team-led responses to risks to health and safety from actual or potential violent, aggressive, abusive or threatening behaviour from patients or visitors, directed internally or externally. One study reported a reduction in code grey events from 538 to 349 events (P = 0.003).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 These codes were called as a result of the behaviour of 370 patients in the pre-period compared with 259 patients in the post-period (P = 0.159).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 An additional study reported a reduction in code grey events in the emergency department from 101 to 88 per month (but this was accompanied by an increase in the number of planned code grey events from 10 to 30 per month for a linked unit).Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40

Examining restraint, all measures of restraint were reduced in both studies.Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 The number of patients experiencing any restrictive intervention was reduced from 338 (12.7%) to 255 patients (10.7%) (P = 0.02).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 The number of physical restraints reduced from 339 (11.3%) to 224 events (9.4%) (P = 0.04).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 Similarly, there was a reduction in mechanical restraint from 275 (9.0%) to 156 events (6.6%) (P < 0.001).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 The use of therapeutic sedation was reduced from 250 (8.2%) to 156 (6.6%) (P < 0.001).Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23 The second study reported a 50% reduction in the total number of patients restrained, from 38 in the pre-period to 17 in the post-period, with an accompanying reduction in the total hours of restraint from 197 to 35 h.Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 The average hours of mechanical restraint for individual patients also dropped from 6.8 to 2.5 h.Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40

The ward environment

Only one study, which was assessed to be at moderate risk of bias,Reference Mok and Walker44 reported data for occupancy rates for the ‘regular stay unit’. These were 94%, 98%, 99% and 95% in the pre-period compared with 89% 91%, 96% and 85% in the post-period.Reference Mok and Walker44 The results are difficult to interpret, as the authors did not report the within-month variance or conduct a statistical analysis.

Total time in crisis and acute care

One study reported changes to the total time in acute and crisis care (total time in the emergency department, crisis unit and in-patient admission). This was reduced from a mean of 100.89 (median 46.15) to 91.00 (median 31.35) h; a difference of around 10 h. Statistical testing used log-transformed data in a mixed model and found a significant reduction (P = 0.03).Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37

Ward admissions and psychiatric holds

One study reported data about psychiatric holds, which can be voluntary or involuntary, are often 72 h in the US and are used for mental health evaluation.Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 The psychiatric hold rate was significantly reduced (42% after the intervention compared with 49.8% before the intervention; difference of 7.8%; P < 0.0001).

All four studies reporting ward admissions reported a significant reduction. In one study, this was reduced from 42% to 25% of patients (P < 0.001).Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24 A further study reported 301 (8.3%) of patients presenting to emergency department were admitted to in-patient psychiatry in the post-period compared with 509 (15.3%) patients in the pre-period, representing a significant difference of −7.0% (95% CI −8.5 to −5.5).Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 A third studyReference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 reported that fewer patients were either admitted to a ward or discharged from the emergency department. Admissions reduced from 47.9% of presenting psychiatric patients to 38.0%. Rates of discharge from emergency department were also reduced from 39.1% to 28.2%. Transfers remained similar. The total number of admissions to ward and transfers reduced from 58.8% to 50.9%.Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 The fourth study reported that 35% (156/435) of the intervention group were admitted to hospital from either the emergency department or the crisis unit (10% (42/435) of these were admitted from the emergency department), compared with 52% (181/348) of the control group,Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39 but these outcomes were assessed as being at serious risk of bias because of the differences between the sites and populations they serve.

The data for ward admissions from these four studies were combined meta-analytically, and a sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding the study at critical risk of biasReference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39 (see Fig. 2(b) for meta-analysis and Supplementary Fig. 4 for the forest plot of the sensitivity analysis). The combined odds ratio is 0.55 (95% CI 0.43–0.68), with an I 2 value of 91% (data from 19 634 patients). The result was effectively unchanged in the sensitivity analysis (combined odds ratio of 0.55, 95% CI 0.42–0.73, I 2 of 94%). The GRADE rating was upgraded to ‘moderate certainty’, meaning that the authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect.

Hospital admissions in follow-up

Two out of three studies reported no difference to hospital admissions in the follow-up period. The rate of hospital admissions across the groups over a 1-month follow-up period was 6.9% compared with 6.7% in one study.Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 A further study, reporting on a unit specialising in helping people who attempted suicide, recorded a reduction in the number of patients who had a psychiatric in-patient admission during a 1-year follow-up in the crisis unit group (24%) compared with (38%) participants in the comparison group, but did not test for significance.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 A final study reported that the 30-day readmission rate for those who stayed in the intervention unit was similar to other patient samples, but this was deemed to be at serious risk of bias as the comparison group(s) were not clearly defined.Reference Schneider and Ross38

Two studies reported LOS for hospital admissions. The first study reported no significant difference between the number of in-patient days when the time spent on the experimental unit was included: 33 (s.d. 73.5) days in the active group and 37 (s.d. 83.0) days in the control group.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 However, when the in-patient days were compared excluding the time on the experimental unit, the difference was significant (z = −5.51, P < 0.001).Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 The second study reported the modal LOS for this outcome: in the pre-period, only those admitted to a ward were included (modal LOS of 5 days).Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 However, it should be noted that many of the stays in the follow-up seemed to be very short visits to the crisis unit, which is driving the modal LOS in the post-period to be 1 day. This introduces bias as the admission criteria for the two groups (stay on crisis unit versus stay on ward) is not comparable.

Clinical and patient experience

There we no significant difference between the groups for clinical and patient experience outcomes. The first study compared scores on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28)Reference Goldberg45 between groups at follow-up and found no significant difference (t = −0.37, P = 0.715) (moderate risk of bias).Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 This study also collected data for the patient reported improvement, and found no difference between the proportions of patients who reported improvement in each group (t = 0.42, P = 0.677).Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 The second study reported no significant effect of treatment on either the General Symptom Index (F(8,112) < 1, P = 0.72),Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 Hopelessness Scale (F(1,110) = 2.14, P = 0.15)Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 or Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) (F(8,110) = 1.03, P = 0.42).Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42

Suicidality

One study described an experimental unit designed for those who had attempted suicide, and is the only study that reported data about changes to suicidality.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 The study concluded that the unit had no impact on the frequency of suicide attempts compared with treatment as usual. There was no significant difference in the probability of repeat suicide attempts in the follow-up period (hazard ratio of repetition for patients in the experimental group compared with the care as usual group was 1.24; 95% CI 0.68–2.27). Congruently, there was no difference in the number of suicide attempts per patient in the follow-up period (z = 0.49, P = 0.62).Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 Patients at high risk of a repeat suicide attempt can be defined by a score of at least four on the Buglass and Horton (1974) Scale.Reference Buglass and Horton46 Using only these patients, a non-significant difference in repeat attempts was found between the experimental and control groups (log rank test = 2.69, P = 0.10).Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42

Follow-up out-patient care

Significantly more patients in the experimental group received out-patient care (including care specifically connected to the unit) in the first year of follow-up (χ2 = 37.42, d.f. = 1, P < 0.001).Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42

Fatalities

One study reported data for any fatalities of study participants.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 In the ‘pre’ sample of 3333 emergency department psychiatric presentations, there was one fatality; and in the ‘post’ sample of 3630 emergency department psychiatric presentations, there were no fatalities. This outcome was not sufficiently powered for conclusions to be drawn, and suicidality was not a specific inclusion or exclusion criteria for the study.

Health economics outcomes

Two studies reported health economics outcomes. One reported a reduction in time spent in the emergency department for those presenting with psychiatric problems, and a congruent decrease in the number of hours (by 1475 h) of one-to-one nursing care in the emergency department in the first 3 months after the unit fully opened compared with the same period in the previous year, translating to an annual reduction in the cost of one-to-one nursing in the emergency department of $120 088 (international dollars).Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 However, neither a denominator or significance test was reported. The second reported additional revenue for the emergency department resulting from the short-stay crisis unit opening of $404 954 (USD) in the initial 6 months and $861 065 annually.Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first systematic review of short-stay crisis units for mental health patients on the crisis care pathway. Units typically have two service-defined objectives: to reduce waiting time in the emergency department and/or to reduce in-patient admissions. Our review is indicative of a significant reduction in both outcomes. Mental health crisis services have been described as being themselves in crisis, experiencing pressure from busy emergency departments and wards operating at or beyond capacity, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.1,Reference Nicks and Manthey3–5,Reference Sampson, Wright, Dove and Mukadam7,Reference Jeffery, D'Onofrio, Paek, Platts-Mills, Soares and Hoppe8 As such, these findings are of interest and relevance to many stakeholders; those designing and commissioning services, service providers, clinicians, patients, carers and bodies assessing the quality of services (e.g. the Care Quality Commission in the UK). Reducing time spent in the emergency department by using short-stay crisis units as part of the crisis care pathwayReference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22 could help to improve the flow of patients through the emergency department,Reference Dawoodbhoy, Delaney, Cecula, Jiakun, Peacock and Tan20,Reference Zeller, Calma and Stone21 and so these findings are potentially important to general hospitals struggling with emergency department capacity and planning.Reference Nam, Lee and Kim2,Reference Nicks and Manthey3 We also found that the likelihood of an in-patient admission for people in crisis was reduced following a stay on a crisis unit (compared with patients not accessing crisis units).Reference Parwani, Tinloy, Ulrich, D'Onofrio, Goldenberg and Rothenberg24,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37,Reference Stamy, Shane, Kannedy, Van Heukelom, Mohr and Tate22,Reference Gillig, Hillard, Bell, Combs, Martin and Deddens39 It is possible that crisis units are functioning to delay in-patient admission,Reference Schneider and Ross38 although in one study the total time spent in crisis and acute care following the index crisis presentation was reduced.Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 There was also a suggestion that short-stay crisis units offer more time to make the most appropriate decision about admission, discharge or community referral when the best course of action is unclear,Reference Lester, Thompson, Herget, Stephens, Campo and Adkins37 indicating the potential for the risk of inappropriate in-patient admissionsReference Stulz, Nevely, Hilpert, Bielinski, Spisla and Maeck17 or premature emergency department discharges to be decreased.

For patients and their carers it may be more important that the unit provides a better patient experience than the chaotic environment of the emergency department,Reference Broadbent, Moxham and Dwyer9 offering an alternative space for stabilisation of crisis and assessment. Four studies included in the review reported providing a more therapeutic environment as a stated aim of the unit.Reference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40,Reference Kealy-Bateman, McDonald, Haber, Green, White and Sundakov41 A key measure related to creating a more therapeutic experience is the use of restrictive interventions,Reference Broadbent, Moxham and Dwyer9,Reference Brady, Spittal, Brophy and Harvey47 with two studies finding a reduction in the use of security and restraint services in the emergency departmentReference Braitberg, Gerdtz, Harding, Pincus, Thompson and Knott23,Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 (although in one of those studies the decrease in security events in the emergency department occurred alongside an increase in security events elsewhere on the pathway).Reference Browne, Knott, Dakis, Fielding, Lyle and Daniel40 In addition, short-stay crisis units do not seem to have significant effects on mental health outcomes, as measured by standardised scales assessing distress, symptoms and hopelessness.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 Two studies assessed the patient experience directly, finding no difference in outcome,Reference Trethewey, Deepak, Saad, Hughes and Tadros25,Reference Spooren, van Heeringen and Jannes43 and no social outcomes were included in any study. As such, we note that data on the patient experience of short-stay crisis units were limited, and it was not possible to draw conclusions on whether crisis units improved the overall patient experience of the crisis care pathway.

Finally, many people presenting in crisis at emergency department are feeling suicidal,Reference Betz and Boudreaux48 and just one study reported outcomes related to suicidality, finding that staying on a short-stay crisis unit did not change the probability or number of repeat suicide attempts.Reference Van Der Sande, Van Rooijen, Buskens, Allart, Hawton and van der Graaf42 Given that managing the risk of harm to self and others is a key focus of mental health crisis care, it is of note that the existing literature does not offer better evidence of the effect of crisis units on suicidality.

Limitations

Where we were able to undertake meta-analyses, we felt that the quality of studies indicated moderate certainty that our estimates of effect were close to the true value, and as such suggest that our findings are of relevance to stakeholders in mental health crisis care. However, we do recognise that differences in short-stay crisis units’ operational structure and issues around capacity elsewhere on the crisis care pathway (e.g. in-patient beds) at a local level are likely to mediate any effect that can be expected of crisis units. Studies reported many outcomes of interest, with data synthesis indicating wide potential benefits of crisis units. However, differences between studies in the way outcomes were reported (for example, reporting median rather than mean values) limited the number of meta-analyses we could perform, and therefore the range of conclusions we were able to draw from the evidence. We were unable to adequately explore the effects of crisis units on patient experience and suicidality, highlighted by researchers on the team working from a lived experience perspective as being of particular importance, limiting the scope of our review. Similarly, there was insufficient evidence reported to properly consider the health economic effects of crisis care units.

Clinical implications

There is evidence to suggest that short-stay crisis units can address service priorities effectively (reducing demand on the emergency department and psychiatric in-patient facilities, decreasing psychiatric hold rates and increasing rates of out-patient follow-up), suggesting that these units offer a useful addition to the crisis care pathway. We note that units tended to focus on either improving outcomes in the emergency department or on psychiatric admissions, and it may be more difficult to configure units in such a way to effectively address both service pressures. When establishing crisis units, it may be sensible to consider the priorities of the particular healthcare context that drive the initiation of these units when thinking about their utility in local services (e.g. in addressing the financial burden of extended emergency department boarding, or lack of in-patient capacity). Given our lack of findings related to patient experience and suicidality, it is also important to consider potential harms of introducing crisis units (e.g. fragmentation of the pathway as a series of very short stays in different facilities).

Future research

As noted above, future research is needed to improve the evidence base for the impact of short-stay crisis units on patient experience, suicidality, and clinical and social outcomes, including longer-term effects. Higher-quality studies, including RCTs, would strengthen confidence in the evidence. Research is needed to investigate the relationship between a unit's aim(s), configuration and outcome(s). This includes system-level studies that examine the role of short-stay units as part of a crisis care pathway, including more research on health economic costs and benefits at both unit and system level.

In conclusion, there is good evidence that short-stay crisis units, provided for people on a mental health crisis care pathway, can achieve the primary goals of reducing pressure on the emergency department and in-patient admissions, and secondary goals of decreasing psychiatric hold rates and increasing out-patient follow-up rates. This is encouraging for service providers who are struggling to manage the flow of patients from emergency department and along the crisis care pathway, and for patients who are not best served by an unhelpful admission and who would benefit from follow-up care. Although the stated purpose of units is also to provide a more therapeutic environment than the emergency department and to improve patient experience, there is limited evidence to suggest the units accomplish these aims. Further research is needed to identify the effects on the patient experience and to ensure that crisis units are best configured to meet the needs of the healthcare system locally.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.534

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.P.G., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the St George's University of London Peer Expertise in Education and Research (PEER) group for their contribution to the design of this project.

Author contributions

K.A., L.P.G, J.L., J.A.S., K.T. and S.G. formulated the research question, designed and performed the study, and wrote the article. E.S., Z.A., G.C., P.P. and A.-L.P. designed the study and wrote the article. H.J., S.J., D.M. and C.C. formulated the research question, designed the study and wrote the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (grant number 17/49/70; https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/49/70). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.