- HbA1c

glycated Hb

Health professionals are crucial in the fight against a number of conditions that impact disproportionately on ethnic minority populations. Approximately 12·5% of UK residents come from a non-white British ethnic back ground, and in some urban areas the proportion is approximately 50%(1). According to the 2001 Census, nearly half (45%) of the minority ethnic population in England lives in the Greater London area, where they form 29% of the population overall(2). South Asians currently represent approximately 40% of the UK ethnic minority population, with individuals or their families, mainly originating from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

With continued migration from South Asia, Europe and elsewhere, Britain has an increasingly multi-ethnic population. This can present a number of challenges to health care professionals when dealing with public health issues linked to diet and lifestyle. This paper focuses on specific conditions that are known to be more prevalent in people of South Asian origin, and are linked to diet and lifestyle. These include type 2 diabetes, CVD and CHD. It should be borne in mind, however, that there are other conditions, for example, osteomalacia and rickets, which are also linked to diet and lifestyle in the South Asian population(Reference Sievenpiper, McIntyre and Verrill3–Reference Holick5). The role of public health and preventive care are pivotal in all such lifestyle diseases.

UK policy background

In 2008, the NHS Review undertaken by Lord Darzi laid special emphasis on creating an NHS that would help people stay healthy(Reference Darzi6). Primary Care Trusts were subsequently charged with commissioning comprehensive well-being and prevention services ‘personalised to meet the specific needs of their local populations’. Six key goals were identified, the first of which was tackling obesity. A Coalition for Better Health was established to focus on combating obesity and providing incentives for primary care to help individuals and their families stay healthy. The following year, the Guide for World Class Commissioners stressed that ‘promoting health and well-being is necessary but not sufficient’, and cautioned that improvements in commissioning and service delivery must ‘not widen the gap between different groups in society’(Reference Shircore7). In February 2010, the Marmot Review proposed an evidence-based strategy for the UK aimed at ‘tackling the persistent problem of inequalities in health and life expectancy’(Reference Marmot8). At the same time, national experts expressed concern that, while the Marmot Review included passing reference to the health disadvantage experienced by particular ethnic groups, it failed to ‘give any meaningful attention to this key dimension in modern British society’(Reference Salway, Nazroo and Mir9). In July 2010, the UK Coalition Government published a White Paper (Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS), which once again placed a strong emphasis on the need to reduce inequalities, stating that ‘the NHS is about fairness for everyone in our society. We are committed to promoting equality’(10). The Equality Act, which came into force in October 2010, gave public bodies a duty, when making decisions of a strategic nature, to have ‘due regard to the desirability of reducing inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage’(11). In November 2010, the Home Secretary announced that the socio-economic duty, created as part of the Act, would now be omitted(Reference May12).

In contrast, there has been a legal requirement to address issues of racial equality for over 20 years in the UK. Furthermore, in the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000, all public bodies, including the NHS and local authorities, were given a statutory duty to make promoting race equality central to the way they work(13). Achieving this goal has apparently not been easy. The 2010 report from the Care Quality Commission concluded that, although all Trusts should have met a minimum standard by 2004 in terms of promoting equality, nearly one in five were still failing to do so by 2009(14). In primary care services also, a recent analysis of data from over 1000 English general practitioner (GP) practices found that all aspects of care were rated substantially lower by respondents from ethnic minority groups than by white patients(Reference Mead and Roland15). The public health White Paper (Healthy lives, healthy people: our strategy for public health in England) proposes that at least 15% of current GP practice payments as part of the Quality Outcome Framework should by 2013 be devoted to evidence-based public health and primary prevention indicators(16). It will become the responsibility of a new body (Public Health England) to decide on the level of investment in Quality Outcome Framework public health primary prevention indicators, based on priorities for improving people's health and reducing inequalities.

If the key goals proposed by Lord Darzi and the challenges identified by the Care Quality Commission are to be addressed, health professionals will need to acquire the knowledge and skills required to meet the needs of a diverse population. Even if ethnic minority groups are provided with the same services as other people, this can still be discriminatory and result in inequalities if services are culturally or linguistically inappropriate. The key factors influencing access to health services, including preventive care, have been well rehearsed(Reference Szczepura17). In future, population health and wellbeing will require partnership working between NHS and Local Authority staff following the White Paper Healthy Lives, Healthy People (18). This has handed responsibility for public health to local authorities (together with a ring-fencing budget) with the aim of tackling issues such as obesity, alcohol abuse and smoking. An initial equality impact assessment has been produced for the White Paper including analysis of any potential impact on racial equality.

Service provision

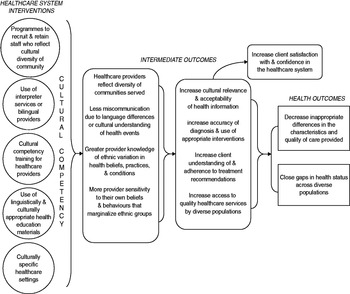

In countries that have experience of population diversity, it is acknowledged that access to services may be poor for certain ethnic minority groups(Reference Szczepura17). Equity in access is defined as ‘care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographical location or socio-economic status’(19). Reviews of the literature identify three key requisites for ethnic minorities: access via appropriate information; access to services that are relevant, timely and sensitive to cultural needs; and services that individuals can use with ease, and with confidence of being treated with respect(Reference Atkinson, Clark and Clay20). Various models have been put forward to make organisations more responsive and to improve cultural competence. As Fig. 1 shows, this can require system-wide changes, especially for lifestyle interventions, because the provider and the patient each bring their individual learned patterns of language and culture to this experience(Reference Anderson, Scrimshaw and Fullilove21). Organisations must also have the capacity to adapt to changes in the communities they serve(Reference Szczepura17). The slow implementation of ethnic monitoring data in the NHS means that, unlike the USA, it has not been possible to develop a UK overview of disparities in service use and outcomes for ethnic minority populations or to monitor these over time(22). Recent moves have focused on improving the use of UK ethnic monitoring data in areas such as cancer(Reference Szczepura17, Reference Iqbal, Gumber and Szczepura23, Reference Lloyd24). The NHS has requested all hospital trusts to record information on the ethnic origin of all patients since April 1996; more recently, this requirement has been extended to all new patients registering with a GP practice. Ethnic monitoring requires the identification of individuals as belonging to one or more groups, defined in terms of their culture and origin(Reference Gerrish25).

Fig. 1. Analytic framework used to evaluate the effectiveness of health-care system interventions to increase cultural competence.

Tackling obesity, the first goal set by the Darzi Review, will require a particular focus on the South Asian population since obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes(Reference Mokdad, Ford and Bowman26). One of the characteristics that most strongly influences occurrence in the UK population is South Asian origin(Reference Stevens and Raftery27, Reference Barnett, Dixon and Bellary28). It has been estimated that 6·4% of the world's adult population now suffers from diabetes, with a prediction that by 2030 the number of people with diabetes will have risen from 285 to 438 million(29). An early analysis of Health Survey for England data found that, although there had been improvements in the achievement of targets for blood glucose, blood pressure and cholesterol, and use of medications over the period 1998–2004, these were not distributed uniformly across ethnic groups(Reference Millett, Saxena and Ng30). Similarly, the latest evidence provided by the British Heart Foundation indicates that, for British people born in South Asia, CHD accounts for about 25% of deaths compared with 15% in the White population; that revascularisation rates are higher in the White population than in those of South Asian origin; and that very few people from ethnic minority groups attend cardiac rehabilitation programmes(31). An earlier Health of Londoners Project, which analysed 1·3 million hospital admissions, also found significantly higher admissions for diabetes for South Asians and mortality rates over four times higher than average among Londoners born in Bangladesh and Pakistan(Reference Bardsley, Barker and Bhan32). UK South Asian adults with type 2 diabetes are reported to access healthcare later than the majority population, with worse disease control, and to be at risk of more adverse outcomes(Reference Barnett, Dixon and Bellary28, Reference McKeigue, Ferrie, Pierpoint and Marmot33–Reference Heisler, Smith and Hayward38).

Because diabetes is recognised as an increasingly important public health concern(29), with established links to CVD(Reference Kannel and McGee39), IHD(Reference Wingard and Barrett-Connor40–Reference McKeigue and Marmot42) and hypertension(Reference Dodson43), researchers have consistently called for improvements to preventive services for South Asians. These include better diabetes surveillance and earlier detection; improved education (for both communities and professions); and tailored prevention programmes including language-competent resources adapted for specific cultural groups, and the mobilisation of networks and community-based social enterprise schemes(Reference Kumar44).

Improving diabetes outcomes for South Asians

In the UK, national surveys indicate that the odds of a person having diabetes are significantly higher for Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi populations than for the White majority population(Reference Zaninotto, Mindell and Hirani45). Diabetes prevalence rates are reported to be three to four times higher in South Asian adults and the disease appears to occur a decade earlier than in the majority White population(Reference Fischbacher, Bhopal and Steiner46, Reference Hanif47). A 2008 review of data from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study similarly concluded that there are sustained ethnic differences, including vascular risk factors, with ‘Indian–Asians’ presenting at a younger age than White Caucasians(Reference Davis48). A more recent UK risk algorithm, based on 2·54 million GP practice patients, also indicates a four- to five-fold variation in 10-year risk of acquiring type 2 diabetes between different South Asian sub-groups, with Pakistani and Bangladeshi men having significantly higher hazard ratios than Indian men(Reference Hippisley-Cox, Coupland and Robson49).

Diabetes appears to be associated with a higher prevalence of CVD in the South Asian population(Reference Zaninotto, Mindell and Hirani45). CVD is the main cause of death in England and Wales, accounting for almost 170 000 deaths in 2009(36). A higher prevalence of CHD and myocardial infarction rates are reported in South Asian populations(31, Reference Patel50), apparently linked to a higher prevalence of diabetes(Reference Patel, Lim and Gunarathne51). However, conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, blood pressure and total cholesterol cannot fully account for observed differences between ethnic groups(Reference Forouhi and Sattar52). A recent study in Tayside, which has a small non-White population, also found a higher prevalence of retinopathy in South Asians, but no evidence of less frequent reviews or poorer recording of BMI and glycaemic control (glycated Hb (HbA1c) levels)(Reference Fischbacher, Bhopal and Steiner46).

Type 2 diabetes, which used to be a condition affecting adults only, is now recognised as an increasingly important public health concern in children. A study of 7300 people with diabetes in primary care found that obesity was more prevalent among younger people than older people from South Asian populations(Reference Millett, Khunti and Gray53). The Child Heart and Health Study in England has recently reported that ethnic differences already exist in the precursors of type 2 diabetes among children aged 9–10; South Asian children were found to exhibit higher HbA1c, fasting insulin, TAG and C-reactive protein, and lower HDL cholesterol(Reference Whincup, Nightingale and Owen54). Adiposity levels could not account for these differences. Other research has also reported higher insulin and leptin at birth for Indian babies, when adjusted for birth weight; this may indicate that prevention of insulin resistance syndrome needs to address regulation of fetal growth in addition to prevention of obesity in later childhood in this population(Reference Yajnik, Lubree and Rege55). The Child Heart and Health Study in England study has also found that ethnic differences in blood pressure begin to emerge in adolescence(Reference Harding, Whitrow and Lenguerrand56).

Identifying obesity risk thresholds

Research has consistently identified that South Asians develop metabolic and vascular complications associated with obesity at a lower BMI and waist circumference than the White majority population(Reference Razak, Anand and Shannon57), and that these differences begin to emerge during childhood(Reference Lakhanpaul and Bird58). Analysis of 2003–2004 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the Health Survey for England shows that in a population characterised as normal weight by BMI, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes will differ by ethnic group(Reference Diaz, Mainous and Baker59). In South Asians, risk appears to be related to the distribution of excess fat rather than to a simple BMI measure(Reference Despres, Lemieux and Prud'homme60, Reference McKeigue, Shah and Marmot61). At a given BMI, South Asians have more intra-abdominal fat that may be an important factor in their development of diabetes(Reference Taylor62). Barker has suggested that such differences might represent a metabolic adaptation to impaired growth in foetal and early infancy; the ‘thrifty phenotype’ hypothesis(Reference Barker, Hales and Fall63). Thus, that nutritional deficiencies in utero result in lower birth weight which can lead to reduced insulin production later in life, resulting in diabetes if insulin production is unable to compensate for increased metabolic demand. An alternative hypothesis (the ‘thrifty genotype’) postulates that it is genetic differences that link low birth weight to adult diabetes(Reference McCance, Pettitt and Hanson64, Reference Singhal, Wells, Cole, Fewtrell and Lucas65). Thus, low-nutrient conditions in utero are thought to result in selective survival of infants with insulin insensitivity, which is beneficial in a low-energy environment but results in increased susceptibility to diabetes in a high-energy environment. Low-birth weight patterns are reported to continue for babies born to UK-born South Asian women similar to those for overseas-born (migrant) women(Reference Harding, Rosato and Cruickshank66). Further studies are examining whether lack of various nutrients in utero can influence the development of circuits that regulate body weight and other cycles of metabolic programming and might correlate with susceptibility to diabetes(Reference Sullivan and Grove67, Reference Saravanan and Yajnik68).

Identifying appropriate obesity risk thresholds for the South Asian population has extremely important public health implications in terms of preventing progression from metabolic syndrome (or ‘pre-diabetes’) to type 2 diabetes, culminating in CVD and CHD. If professionals and patients are unaware of potential differences they may underestimate the risk associated with a particular BMI in ethnic individuals, resulting in increased risk of diabetes and associated CVD in the South Asian population(Reference Hanif47). The use of the original WHO definition of obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) initially led to reports that the UK South Asian population was less obese than the White majority population and therefore at lower risk(36, Reference Williams, Bhopal and Hunt69). In 2004, the WHO introduced a differential threshold for South Asians; cut-offs were reduced to BMI>23 kg/m2 for overweight and BMI>25 kg/m2 for obese(Reference Lee, Bacha and Arslanian70, 71). The application of these lower thresholds identifies higher obesity levels in the South Asian population and therefore greater risk(72). The South Asian Health Foundation has strongly recommended the use of these revised cut-offs for British South Asians, but this has not yet been formally adopted in the NHS(73). However, the Indian Health Ministry has recently announced a national adjustment to criteria for defining obesity in their country(Reference Misra, Chowbey and Makkar74). Although obesity also places young people at increased risk, there is no agreed international definition for children(Reference Zimmet, Alberti and Kaufman75). Waist circumference is recognised as an independent predictor of insulin resistance, raised lipid levels and increased blood pressure in childhood(Reference Lee, Bacha and Arslanian70, Reference Bacha, Saad, Gungor and Arslanian76). Therefore, the International Diabetes Federation has recommended the use of a waist circumference >90th centile as a cut-off for all children; it has also advocated the use of ethnicity-specific centile charts(Reference Zimmet, Alberti and Kaufman75).

Diet and lifestyle

Diet can make a substantial contribution to obesity and to the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes(Reference Lovegrove77). In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has recently highlighted prevention of progression from ‘pre-diabetes’ to type 2 diabetes as an important public health aim and initiated a consultation to develop guidance for high-risk groups (http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PHG/Wave19/62). A healthy diet low in fat (particularly saturated fat) and high in fibre and complex carbohydrates can help prevent or delay diabetes development(Reference Wyness78). Low levels of physical activity in certain ethnic groups also mean that strategies to reduce diabetes risk will need to achieve their main impact through dietary interventions in these populations(Reference Netto, Bhopal, Khatoon, Lederle and Jackson79, Reference Fischbacher, Hunt and Alexander80). Successful changes to dietary lifestyle require an understanding of cultural beliefs about a healthy diet and about the medicinal benefits of certain foodstuff.

The diet of ethnic minority groups varies widely(Reference McKeigue, Marmot and Adelstein81). The question of whether certain aspects of the South Asian diet predispose individuals to glucose intolerance remains largely unanswered(Reference Hanif47). High-quality evidence from prospective trials for determining the role of specific nutrients in diabetes prevention and control is missing(Reference Wyness78). However, there is evidence that dietary habits worsen following migration. For example, second-generation offspring of former migrants are reported to adopt British dietary patterns, with increased fat and reduced vegetable, fruit and pulse consumption compared to first-generation migrants(Reference Landman and Cruickshank82). A review of European dietary habits of ethnic minority groups has similarly identified that mixed food habits are emerging in second and third generations, most likely due to acculturation and adoption of a Western lifestyle(Reference Gilbert and Khokhar83). In the UK, a culture of multiple meals, large portion sizes and snacking between meals, which can all contribute adversely to weight control, has been reported in some South Asian populations. For example, Bangladeshi and Pakistani families may eat two traditional meals in the course of the same evening, with children eating a meal both before and after attending religious classes(84). In contrast, in Gujarati Hindu and Punjabi Sikh households smaller portion sizes, fewer multiple evening meals and more control of children's snacking has been reported. The childhood Child Heart and Health Study in England study has identified that South Asian children have a higher intake of total fat, polyunsaturated fat and protein, and carbohydrates (particularly sugars), with lower vitamins C and D, than the majority population(Reference Donin, Nightingale and Owen85). These differences appear to be especially marked for Bangladeshi children. In early infancy, and even before, additional dietary triggers may be associated with increased risk of diabetes. These include excessive maternal weight gain during pregnancy and shorter-than-recommended duration of breast feeding(Reference Wojcicki and Heyman86). South Asian populations show worryingly low rates of breast feeding, despite professional encouragement(Reference Lakhanpaul and Bird58). Evidence is also emerging that early exposure to complex proteins in breast milk supplements could influence risk of type 1 diabetes in children with a genetic susceptibility, although there is no evidence of links to type 2 diabetes(Reference Knip, Virtanen and Seppa87, Reference Harlan and Lee88).

Research on beliefs about diet indicates that British South Asians consider their family's diet to be healthy because cultural dishes are ‘prepared from scratch’(84). Research in a Bangladeshi population with diabetes has also highlighted the importance of beliefs about ‘beneficial foodstuffs’ which can adversely affect diabetes management(Reference Choudhury, Brophy and Williams89). A study among Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Indian communities in Edinburgh similarly concluded that successful CHD prevention initiatives need to identify deep-rooted influences on health behaviour(Reference Netto, McCloughan and Bhatnagar90). Religious observance can also affect nutrient intake and therefore diabetes control. For Muslim populations, such as those from Pakistan and Bangladesh, there are certain religious fasting requirements which individuals are expected to meet(84). For example, there is evidence that dietary changes during the month of Ramadan can affect clinical and metabolic parameters in type 2 diabetic patients(Reference Sari, Balci, Akbas and Avci91). Although people with diabetes can be exempted from this religious obligation, research has shown that a high proportion do fast during Ramadan(Reference Hui, Bravis and Hassanein92). The original nutritional advice for Ramadan(Reference Connor, Annan and Bunn93) has recently been updated to provide professionals with improved guidelines for management of diabetes during this period(Reference Karamat, Syed and Hanif94).

Improving the evidence base on ethnicity and health

Fundamental to improving the health and well-being of ethnic minority populations is a need to improve the evidence base, and to increase knowledge and understanding among health professionals. The Acheson inquiry into inequalities in health commented on the lack of such an evidence base(Reference Acheson95), and other authors have identified the low levels of recruitment of ethnic minority patients to clinical trials as a problem(Reference Hussain-Gambles, Atkin and Leese96). At the same time, the challenge faced by professionals in attempting to identify and assess the research evidence published on ethnicity and health is substantial. Poor indexing by journals makes identification of potentially relevant articles difficult, requiring complex search strategies and considerable expertise. Once identified, articles vary considerably in the categories used to define ethnic groups, with lack of consensus on the optimum categories often making comparison of studies impossible. Assessment of the quality of the research reported is also complicated by the wide range of methods used in studies, and the very few randomised controlled trials which limits the possibility of formal meta-analysis. All these factors present a considerable challenge for development of an evidence base on ethnicity and health. There are also issues beginning to emerge for assessing equity in systematic reviews(Reference Tugwell, Petticrew and Kristjansson97).

In order to support the development of such an evidence base, a web-based specialist library for ethnicity and health was established in 2007 as part of a new NHS knowledge service. The aim was to identify evidence to help improve the health of minority ethnic groups and migrant populations living in Britain. In April 2009, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence launched NHS Evidence. This has a broader range of collections and enhanced electronic functionality. The objective is to provide high-quality, evidence-based information across health and social care at a local and national level to inform decision-making. The Specialist Collection on Ethnicity and Health is provided by the UK Centre for Evidence in Ethnicity, Health and Diversity(98).

Defining ethnicity

Defining ‘ethnicity’ is not a simple matter(99). The concept recognises that people identify themselves with a social grouping on cultural grounds including language, lifestyle, religion, food and origins. Furthermore, in a world of migration and mixing, it is essential to recognise that these cultures and societies are dynamic rather than fixed. There has been considerable debate and controversy about the categories used for defining ‘ethnic minorities’(Reference Bhopal, Phillimore and Kohli100–Reference McKenzie and Crowcroft102).

Information on ‘ethnicity’ must be collected consistently in order to be of use. Data can be collected in a number of ways. One of the least threatening and most commonly used by front-level staff is to ask about language. This can be seen to relate directly to the needs of the client; unless a person's preferred language is recorded providers may have no idea of the need for interpreting and translation services. However, effective communication may require awareness of other aspects of culture apart from language(Reference Szczepura, Johnson and Gumber103). Religion can also play an important part in communication, especially in the provision of care for people in distress. Most patient records do have a space for religion, although it is not always completed. It was only after debate and lobbying that the Office of National Statistics agreed to add a new question on religion to the Census in 2001. However, the most common indicator used in official records is birthplace. Information on birthplace is recorded on most identity documents, and is used to analyse data such as that collected on death certificates. Unfortunately, it provides a poor indicator of cultural or ‘ethnic’ origin since more than half of the ‘minority’ ethnic population is now born in Britain. Nationality is an equally problematic categorisation; it is essential not to confuse the idea of cultural identity with the question of the rights of the citizen to state-funded services. Although the terms used in the 2001 Census provide a suitable baseline(104), additional information on language and literacy, and migration history may be required for service planning and monitoring of uptake(Reference Szczepura17).

The crucial point made by many authors is that the categorisation used must be ‘fit for purpose’, i.e. it must be relevant to the delivery of the service being considered and to the recognition of client need. As stated by the Migration Policy Group in Brussels:

The trouble with using nationality, birthplace, ethnic origin or language spoken at home as indicators of ethnic categories is that this implicitly assumes that such criteria all refer to the same clear-cut entities … It is more effective to use different criteria to pursue different policy objectives …(Reference Vermeulen105)

In order to encompass the wide range of available literature, The Specialist Collection on Ethnicity and Health uses a broad-ranging Thesaurus(Reference Presley and Shaw106). This is able to accommodate papers and reports that use crude level meta-categories such as ‘ethnic minority’, ‘black’, ‘migrant’ as well as those which provide more detailed information on ethnicity (including language, religion and other key categories such as Roma or travellers, refugees and asylum seekers).

Much of the literature still uses crude meta-categories. These are likely to include sub-populations of diverse cultural, linguistic, religious and biological or genetic origin. For example, within a meta-category like ‘South Asian’, the three main groups (Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian) will exhibit considerable differences in terms of their health status as well as their expectations and priorities. Also, even the population labelled as ‘Indian’ will include a number of different religio-linguistic groups (Sikh Punjabis, Muslim Gujaratis and Hindus of various linguistic origin), while others such as the ‘Pakistani’ population may be associated fairly closely with particular cultural characteristics such as language (Urdu) and religion (Muslim), although it is dangerous to assume that this will always be the case(Reference Modood, Berthoud and Lakey107, Reference Johnson, Owen and Blackburn108). A few published articles go into this level of detail, but research that observes these distinctions is more likely to be generalisable, at least within the sub-category identified. Similarly, although there has been a steady growth in the collection of ethnic monitoring data in the NHS, there is relatively little report of its use in research publications. In fact, reference to minority groups in the abstracts or key words of many papers proves on examination to either consist of a recommendation that ‘more research is needed on ethnic minorities’ or to explain that ‘non-English speakers’ have been excluded from a particular trial.

Evidence on lifestyle interventions

Even though there are a large number of articles on ‘ethnicity and health’, there is a shortage of high-quality evidence. Where research is available, it often comes from other countries so that care is needed in generalising any findings to the UK. Ethnic minority populations will differ making comparisons difficult, and barriers to accessing healthcare in insurance-based systems such as the USA may accentuate any underlying ethnic differences. Within a particular ethnic group, there may also be disproportionate effects of age and gender, compared to the majority white population. For example, the older generation of South Asian immigrants has a poorer understanding of health- and social-care systems than the younger population(Reference Atkinson, Clark and Clay20). Over time, communities will become more familiar with services as they need to access them e.g. first maternity and later palliative care. Similarly, effective communication of lifestyle messages will depend on the language and literacy profile of the population targeted. In the South Asian community, the ability to speak English declines with increasing age, is lower for women than men, and is much poorer for those born outside the UK. However, there are also variations between sub-groups(Reference Szczepura, Johnson and Gumber103). Thus, South Asian women especially in Muslim cultural groups are the least likely to speak or read English: they may also not be literate in their ‘mother tongue’. Older people of Bangladeshi origin in particular have a limited ability either to understand spoken English or to read any language. Even in the early ‘middle-age’ group(Reference Millett, Saxena and Ng30–Reference Hippisley-Cox, Coupland and Robson49), there are significant numbers of Bangladeshi and Pakistani women who will be essentially illiterate in any language, and who also do not speak English. Also, some languages, notably the Sylheti dialect of Bangladesh, do not have an agreed written form. At the same time, those who have acquired English as a second language often lose this ‘learned’ ability as they get older. With the migration of new groups (including asylum seekers and refugees) and the learning process undergone by settlers, the NHS faces a constantly changing picture of language needs.

The value of service-led lifestyle interventions targeted at people with increased risk of diseases such as diabetes is promising, but not conclusive. As a chronic condition, type 2 diabetes is associated with significant morbidity, leading to reduced quality of life over time as the disease and its complications affect the physical, mental and social well-being of patients(Reference Gujral, McNally, O'Malley and Burden109–Reference Harris112). A systematic review of primary care interventions targeted at minority ethnic populations has concluded that case management in primary care (with specialist diabetes nurses, dieticians and community health workers) can improve HbA1c levels and cardiovascular risk factors, and that use of link workers from the minority ethnic community can lead to improved cardiovascular risk factor control(Reference Saxena, Misra and Car113). A subsequent large randomised controlled trial that evaluated the use of link workers to encourage dietary and lifestyle changes in South Asians with diabetes (United Kingdom Asian Diabetes Study) recorded significant improvements at 2 years in diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure but not in HbA1c (Reference O'Hare, Raymond and Mughal114, Reference Bellary, O'Hare and Raymond115). Similarly, a primary care intervention (Khush Dil) for South Asians who attended health visitor-led screening clinics in Edinburgh found a positive impact (based on self-report) for CVD indicators, but the authors concluded that a controlled trial would be necessary to confirm effectiveness(Reference Mathews, Alexander, Rahemtulla and Bhopal116). A trial is currently underway (ADDITION-Leicester) in a multi-ethnic population with type 2 diabetes, half of whom will receive a multi-faceted cardiovascular risk intervention(Reference Webb, Khunti and Srinivasan117).

In contrast, evidence on the value of patient education per se in improving diabetes self-management is more limited. A Cochrane review of the evidence on self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with various chronic conditions could identify only limited impact in the general population(Reference Foster, Taylor and Eldridge118). Another Cochrane review similarly found no significant differences in HbA1c levels between individual patient education and usual care for a general population with type 2 diabetes(Reference Duke, Colagiuri and Colagiuri119). However, there appears to be some evidence of effectiveness of educational programmes when targeted at ethnic minority populations, although a systematic review of these studies has highlighted the difficulty of designing and assessing such programmes(Reference Khunti, Camosso-Stefinovic and Carey120). A Cochrane review has identified that culturally appropriate health education for patients with type 2 diabetes can provide some improvement in glycaemic control in the short to medium term(Reference Hawthorne, Robles, Cannings-John and Edwards121, Reference Hawthorne, Robles, Cannings-John and Edwards122). More recently, it has also been reported that a tailored (Ramadan-focused) education programme can be effective in empowering patients to change their lifestyle while minimising the risk of hypoglycaemic events during this period(Reference Bravis, Hui and Salih123). Other researchers have also shown that provision of translated materials for patients can improve outcomes(Reference Hawthorne124). However, community-based workers and primary health-care practitioners can find it difficult to access quality-assured translated resources(Reference Kumar44).

Effective dietary interventions to tackle obesity, and therefore improve diabetes and CVD outcomes, require intervention across the entire life course(Reference Stender, Burghen and Mallare125, Reference Netto, Lederle, Khatoon and Jackson126). In terms of dietary intervention specifically targeted at ethnic minorities, a 2008 literature review could identify only two such studies in the UK(Reference Netto, Bhopal, Khatoon, Lederle and Jackson79). Both focused on the South Asian community and targeted women using either trained community members acting as facilitators and leaders of cookery clubs(Reference Snowdon127) or dietitians and fitness instructors to run healthy eating and exercise groups(Reference Williams and Sultan128). The results suggest that targeted interventions can be effective, especially if these are built on existing community links and involve engagement with extended family members and community leaders as recommended by the Department of Health(84). A new wave of community-based social enterprise schemes, such as Apnee Sehat (‘Our Health’), are now being established by Britain's South Asian community to meet the needs of local people through tailored lifestyle programmes, including supervised cooking sessions, shopping tours and educational DVD for patients and professionals(129). More recently, charities such as the British Heart Foundation have started to deliver training courses to improve the knowledge of health trainers in voluntary and community organisations, with some success(Reference Tozer, Aubery and Gill130). For children, lifestyle modifications can be achieved by motivating and empowering parents in the context of the community in which they live. A Cochrane review of obesity intervention programmes concludes that, in general, participatory ‘family based lifestyle interventions with a behavioural programme’ are most likely to succeed in children(Reference Oude Luttikhuis, Jansen, Shrewsbury and O'Malley131). In the USA, the ‘Let's Move’ campaign against childhood obesity launched in 2010 also aims to empower parents and improve access to high-quality foods in all communities(Reference Wojcicki and Heyman86). Diabetes UK has recently identified the need for more research in the area of tailored interventions for South Asians(Reference Khunti, Kumar and Brodie132). The Charity has also produced advice and resources for diabetes professionals, including a Toolkit to enable community and religious leaders to host Diabetes Awareness sessions for people from the South Asian communities(133).

Conclusions

Addressing the needs of ethnic communities and linguistic groups, each with their own cultural traits and health profiles, presents a number of challenges to health-care systems. This can require system-wide changes especially for lifestyle interventions (see Fig. 1). Because the provider and the patient each bring their individual learned patterns of language and culture to this experience, communication is paramount. Behaviour change will require attention to context, including the needs of the person seeking to transmit information, as well as the characteristics (language, literacy and culture) of the intended recipient. Messages must be specifically tailored to their audience, taking religious and other beliefs and practices into account. Information from official sources may have less impact if not supported by personal experience and information from community networks. This can ensure a higher level of relevance for the issues being communicated.

Culturally competent health-care systems (those that provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services) have the potential to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. When people do not understand what their health-care providers are telling them, and when providers either do not speak the patient's language or are insensitive to cultural differences, the quality of care and improvements in lifestyle can be compromised. This can lead to lower patient satisfaction with care, fewer improvements in health status, and inappropriate racial or ethnic differences in use of the services offered.

Over recent years there has been a large expansion in the literature that could potentially support provision of culturally appropriate care. Extensive evidence has emerged from countries and regions experiencing increased population diversity, including the USA, Australia, Canada and the UK. At the same time, there has been little attempt to assess this evidence and provide information for practitioners. In the UK, this has been addressed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence with the establishment of an on-line specialist collection on ‘ethnicity and health’ (http://www.library.nhs.uk/ethnicity).

Acknowledgements

The author declares no conflicts of interest. Thanks are due to NHS Evidence, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence which supports the activity of the NHS Evidence Specialist Collection for Ethnicity & Health.