Victor Turner (Reference Turner1967, 36) described symbols as “forces.” They were for him “determinable influences inclining persons and groups to action.” By tapping into “human interests, purposes, ends, and means” (Reference Turner1967, 20), symbols affected social conduct. Turner here built on Durkheim’s earlier notion of “religious forces,” developed in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. The latter, although operating in the human mind, acted as “material forces which mechanically engender physical effects” (Reference Durkheim and Swain[1912] 1969, 190), as when individuals or groups engage in prescribed ritual behaviors.

In this essay, I analyze one complex symbol, a motivational video produced by the motorcycle manufacturing company, Harley-Davidson, Inc. I use the term “symbol” advisedly, to make obvious the connection to Turner’s work and also because this usage has currency with business people and the public more generally, for whom “symbols” are socially prominent signs, such as the American flag, Christian cross, swastika, Star of David, or skull and crossbones.

At the same time, the popular usage lacks the analytical clarity of the Peircean distinctions, where the same word appears but with more precise meaning in his trichotomy of the sign mode: icon, index, and symbol. Indeed, a symbol in the popular sense is a complex, cognitively discrete bundle of icons, indices, and symbols in the Peircean sense.Footnote 1 Following Sapir’s (Reference Sapir1934) distinction, the Peircean symbol could be glossed as “referential symbol” and the Turnerian symbol as “condensation symbol.” As Turner (Reference Turner1967, 29) explains, referential symbolism requires “formal elaboration in the consciousness,” while condensation symbolism “strikes deeper and deeper roots in the unconscious, and diffuses its emotional quality to types of behavior and situations.”

My contention in this essay is that the Harley-Davidson video, as condensation symbol, does, indeed, exert a kind of “force,” as Turner proposed. In other work (Urban Reference Urban2001, Reference Urban2010) I argue that culture—as socially learned and socially transmitted—is impelled and modified in its motion by forces. My goal in analyzing the video will be to link this circulatory or motional idea of force to the cognate notions developed by Turner and Durkheim, specifically as manifested in the corporate motivational video.

As I hope to show, the video is about group building—the collectivity—as in the case of the Ndembu mudyi tree analyzed by Turner. Similarly to the Ndembu, where conflict arose around the separation of mothers and daughters, internal strife because of corporate restructuring threatened the York manufacturing facility at the time the video was made. The force of the symbol in each case was to realign individual goals and sentiments with those of the collectivity. What I add to Turner’s account, however, is the insight that such a process is one involving motion, as the orientation to the collectivity gets transmitted to those who interact with the symbol. Further, I argue that the force operative, in this case, is interest. A semiotic analysis of the symbol allows us to break open the object of interest—the symbol—in order to better understand the nature of the force it exerts.

In the framework of motion I am presupposing here, interest is one of the four great forces affecting cultural motion. A given aspect of culture moves (or is inhibited in its motion) because people are attracted to it (or repulsed from it). Interest in this sense is linked to the concept of utility in economics, although it more explicitly acknowledges the role of affect. However, other forces are at work as well in the motion of culture. Some aspects of culture get perpetuated because they have been perpetuated in the past, that is, thanks to inertia. Then there is the active force of metaculture or culture that reflects back on other culture, as, for example, when a film review inclines us to want to watch a particular film or word of mouth about a restaurant gets us to want to dine there.Footnote 2

My proposal here is that the Harley-Davidson video shares symbolic characteristics with the milk tree or mudyi analyzed by Turner. However, the video is also significantly different. The Ndembu symbol is confined in its operation to a preexistent group. It is carried forward through time via inertia and also metaculture (if Durkheim is right about the role of duty in relation to religious tradition). In addition, the symbol likely kindles interest in some if not all participants, for example, members of each new generation or even those who have not contemplated the symbol since the previous ritual. While the Harley-Davidson video is a complex condensation symbol, including component symbols (American flags, Harley-Davidson logos, etc.) that have a greater time depth, it is also a piece of culture created in the here and now. Its circulation depends largely on the interest people have in it, on the emotions it is capable of kindling.

Additionally, as I propose to show, the interest can be both positive and negative, with some people feeling inspired by the video and identifying with it and the Harley-Davidson company, and others actively disliking the video and disidentifying with it. For this reason, the symbol exerts a differentiating force within social space, acting as a boundary marker and sorter, a kind of Maxwell’s demon counteracting the force of entropy.

Brand and Motivation

The body of recent anthropological literature with which the present research most closely articulates is that concerning brands and branding (Coombe Reference Coombe1996; Moore 2003; Holt Reference Holt2004; Manning Reference Manning2010), along with the considerable cognate ethnographic research done inside advertising firms or for firms as brand consultants (McCracken Reference McCracken1990, Reference McCracken2005; Moeran Reference Moeran1996; Mazzarella Reference Mazzarella2003; Malefyt De Waal and Morais Reference Malefyt De Waal and Morais2012; see also Foster Reference Foster2008). Manning (Reference Manning2010) describes two phases in the brand research, which he calls “Saussurean structuralist” and “poststructuralist.” The former, he argues, is mainly concerned with brands as types, in the linguistic sense, contrastive elements within a Saussurean system of sign contrasts. The distinctiveness of the brand is the main concern. The latter, more recent “poststructural” phase is one “in which the omnivorous associationism of brand … not to mention rampant anthropomorphism, comes to approximate the fetish” (Manning Reference Manning2010, 36).

With the exception of Foster (Reference Foster2008), there seems to be little or no awareness in most of the recent anthropological literature that a parallel can be drawn between branding and totemism, a phenomenon of great interest to earlier generations of anthropologists, including Durkheim (Reference Durkheim and Swain[1912] 1969) and Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss and Needham[1962] 1963). However, the relationship has been recognized in the business literature more generally (Cayla Reference Cayla2013). Within anthropology, Foster (Reference Foster2008, 81) suggests that mass-mediated forms, such as are governed by trademark and contribute to brands, “circulate with enough currency to provide people with everyday idioms of expression, as Emile Durkheim once noted of totems.” As in the case of totemism, they make “society imaginable and intelligible to itself in the form of external representations” (Mazzarella Reference Mazzarella2004, 346).

I take note of this connection not out of antiquarian interest but because of the curious chronological reversal in the relationship between totemic and branding research as regards structuralism. Whereas Durkheim and early thinkers focused attention on the nature of the relationship individuals and groups had to the totemic emblem, Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss[1962] 1966, 224) seemed to put an end to investigation of the relationship between individual/group and totem through his Saussurean insight: “totemism is based on a postulation of homology between two parallel series—that of natural species and that of social groups—whose respective terms, it must be remembered, do not resemble each other in pairs. It is only the relation between the series as a whole which is isomorphic: a formal correlation between two systems of differences.” On analogy to brands, his interpretation, like Manning’s (Reference Manning2010, 36) account of the structuralist phase of branding, suggests that there is no correlation between, say, Mac users and the Macintosh brand, but only contrasts between the Macintosh and other brands, on one level (the emblem or signifier level), and Macintosh users and other users, on another level (the signified or social group level).

The move toward a poststructuralist (or, better, postmodern) view of branding, with its “omnivorous associationism of brand” and reawakening of the fetish, directs attention in archaeological fashion to the earlier stratum beneath Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism, that is, to the connection between brand and individual/group. Some brands fit into and form part of lifestyles, and so are experienced as closely tied to individuals and the groups with which they align. The Macintosh user or the Harley rider is actually connected with the computer or motorcycle in an experiential way, just as Durkheim surmised clan members were to their totem.

I suggest that for symbols such as the Harley-Davidson motivational video or the Ndembu mudyi tree, the connection depends upon a kind of force. In the Harley-Davidson case, especially, and with brands more generally, the force is interest, with the individual being attracted to the brand products because of emotions that arise through interactions with them. In the case of totemism, according to Durkheim, at least, the force is metacultural, as if the individuals were commanded by tradition and felt themselves compelled to obey, as if they were fulfilling their duty. Undoubtedly, however, interest played some role as well.

From our twenty-first-century vantage, of course, we can appreciate that the contrastive and fetishistic (or structuralist and postmodern) interpretations of totems, as well as brands, are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are essentially related. The greater the contrastive impetus (as in the 1980s Mac vs. PC wars), the greater the fervor of attachment to the brand, just as war between nations tends to increase patriotism.

Many of the people interviewed in the course of the present research believed the Harley-Davidson video to be a commercial, although others felt it was not. The interpretation of the video as a commercial suggests its connection to brand. The assumption underlying my own analysis is that the video was initially designed as a morale builder or revitalization video for those demoralized by the York manufacturing facility restructuring, which affected not only workers at the Harley-Davidson plant in York, Pennsylvania, but virtually everyone in that small city of about 43,000 people. However, Harley dealers around the country did pick up on the video and put it on their websites, indicating that it became a commercial, even though it is less about the motorcycle and more about the people who make it. The deployment of the video by retailers on websites suggests, indeed, that the video exercises an attractive force over at least some people, notably those closely aligned with the Harley-Davidson brand.

In what follows, I first provide an analysis of the video as a “dominant symbol,” in Victor Turner’s (Reference Turner1967) sense, breaking it into its constituent condensation symbols and showing how it works to bring about what Turner (Reference Turner1967, 36) called the “transference of affectual quality.” I follow that by an account of the conflictual circumstances surrounding the creation of the video, and with respect to which it is apparently a response. Finally, I turn to interview data shedding light on various constituent symbols of the video as well as on their role in the operation of interest as a force—both attractive and repulsive. This last is the semiotic attempt to fathom the symbol as Maxwell’s demon, operating within a large-scale social space, creating or maintaining distinctions within that space.

Objective Characteristics of the Symbol

The mudyi or milk tree, also called the African rubber tree, has a salient physical characteristic. When cut, its bark exudes “milky beads,” a feature indexically associated with nurturance, bonding, and togetherness owing to its iconic resemblance to breast milk (Turner Reference Turner1967, 20). At the highest plane, Turner argues, the tree comes to stand for the “unity and continuity of Ndembu society” (21).

Of course, there are obvious differences in the objective characteristics of the symbol between a kind of tree and a video. First, the video as symbol includes words and music as part of its formal observable properties. In the Ndembu case, words and music are part of the ritual in which the milk tree plays a role, but they are not properties of the milk tree per se. Second, the video unfolds in time through watching (and re-watching), whereas ritual unfolds in time around the milk tree. Third, the milk tree as symbol is part of traditional Ndembu culture, not invented by the present generation; the video, obviously, is a present-day creation, part of the self-conscious deployment of culture by and within a corporation, even though it employs traditional constituent symbols.

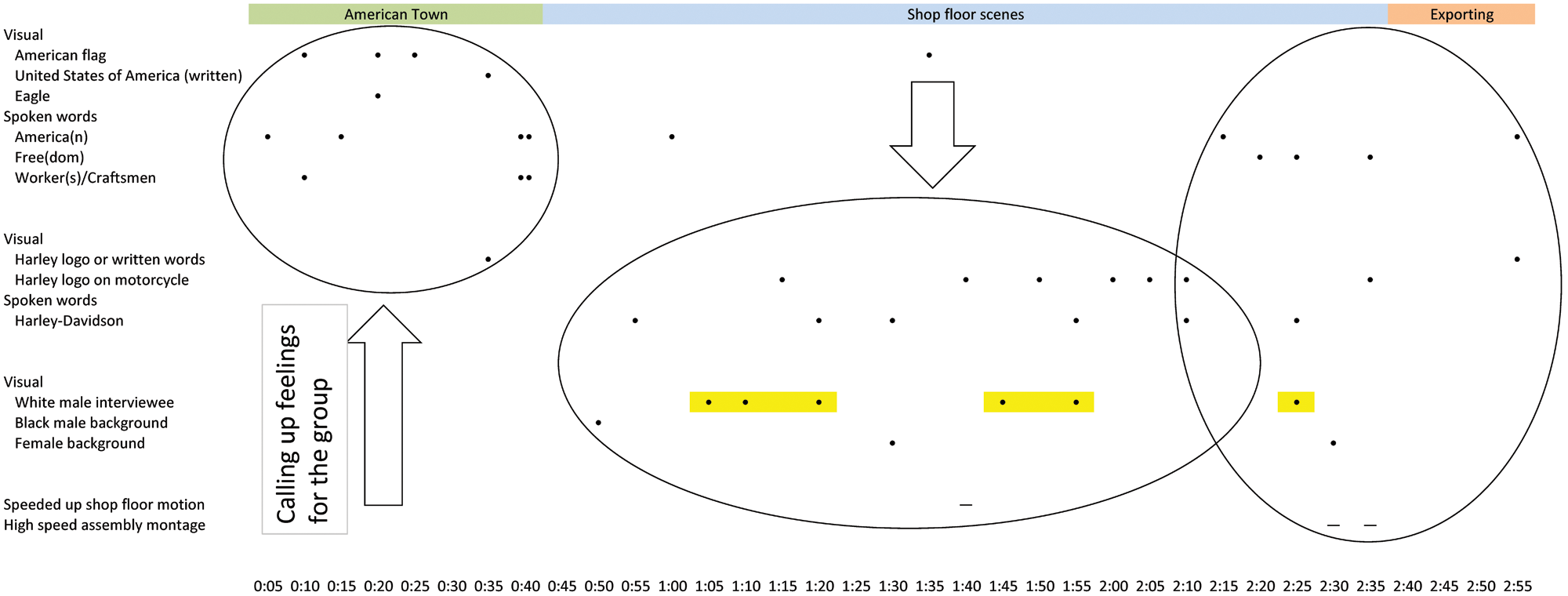

Figure 1 is a summary representation of the objective characteristics of the video. The horizontal axis of the diagram is a timeline of the unfolding video, known on the web as “Harley-Davidson York Transformation.” The video lasts just under three minutes.

Figure 1. Objective characteristics; “transference of affectual quality”

The vertical axis of this figure distinguishes groups of related constituent condensation symbols within the video. The three main groups are those pertaining to (1) America and American small town or small city life; (2) the Harley-Davidson corporation; and (3) gender/ethnicity characteristics of individuals figuring into the background of scenes, as well as the three main interview subjects featured in the video, all white males. I will argue that the intended symbolic force of the video pertains to the relations between the first two. However, the third as well, as the present research unfolded, proved to be a factor in the force field.

For the first two groups, the figure distinguishes along the vertical axis between visual signs and spoken words. The visual signs in the first group that are marked in the figure include images of the American flag and of the eagle. This group also includes the written words United States of America. The spoken words marked, in this case, are America or American, Free or Freedom, and Worker(s) or Craftsmen. For the second group, the visual signs are the Harley-Davidson logo (e.g., on a flag or on a motorcycle), as well as the written words Harley-Davidson. The vertical category of gender/ethnicity distinguishes white male from black male from white female.

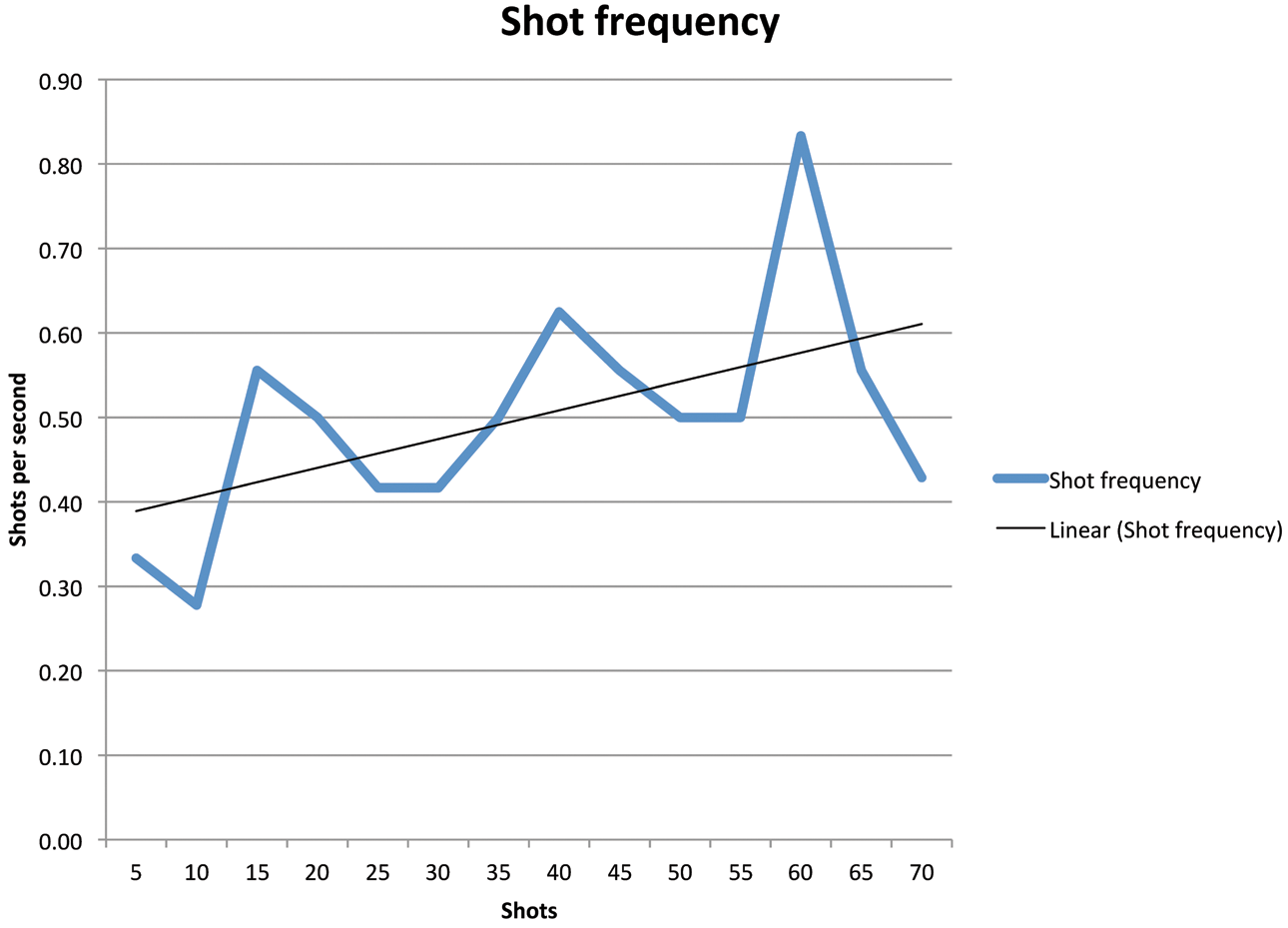

A fourth group on the vertical axis marks a speeded up segment of the video, as well as a rapid succession of still images creating a sense of speeded up motion. I have treated shot frequency in a second figure (fig. 3 below), which I will discuss subsequently. While shot frequency manipulation is a well-known filmmaking technique, it operates typically beneath the level of awareness of the average viewer, though it influences their affective experience. A montage of stills, in contrast, is more readily accessible to viewer awareness.

My central contention regarding the constituent signs depicted in figure 1 is that, as Turner argued for the Ndembu mudyi tree, the overall symbol calls up feelings—in this case feelings about America, small town life, and craftsmen. Following Turner, the first segment of the video, circled in figure 1, represents the sensory or “orectic” pole of the symbol. This is the pole that taps into feelings and summons emotions. It calls forth through its interpretation a sort of Jeffersonian image of belonging.

In the case of the mudyi or “milk tree,” the orectic pole is associated with the milky sap produced when the bark of the tree is cut. According to Turner, the milky sap is iconic with mother’s breast milk and thus calls forth warm feelings of attachment between mother and child. The intent of the Harley-Davidson video, I believe, is to summon warm feelings of attachment to America and its way of life, including the American worker as craftsman.

The focus of the video shifts in the second segment, again circled in figure 1, to the interior of the Harley-Davidson York manufacturing facility. The signs in this segment pertain to what Turner calls the “ideological pole” of the symbols. The structure suggests that, as in the case of the mudyi or milk tree, the symbol effects a “transference of affectual quality.” The ideological content becomes imbued with feelings. That transference is solidified in the third segment of the video when signs pertaining to America are intermingled with Harley-Davidson signs.

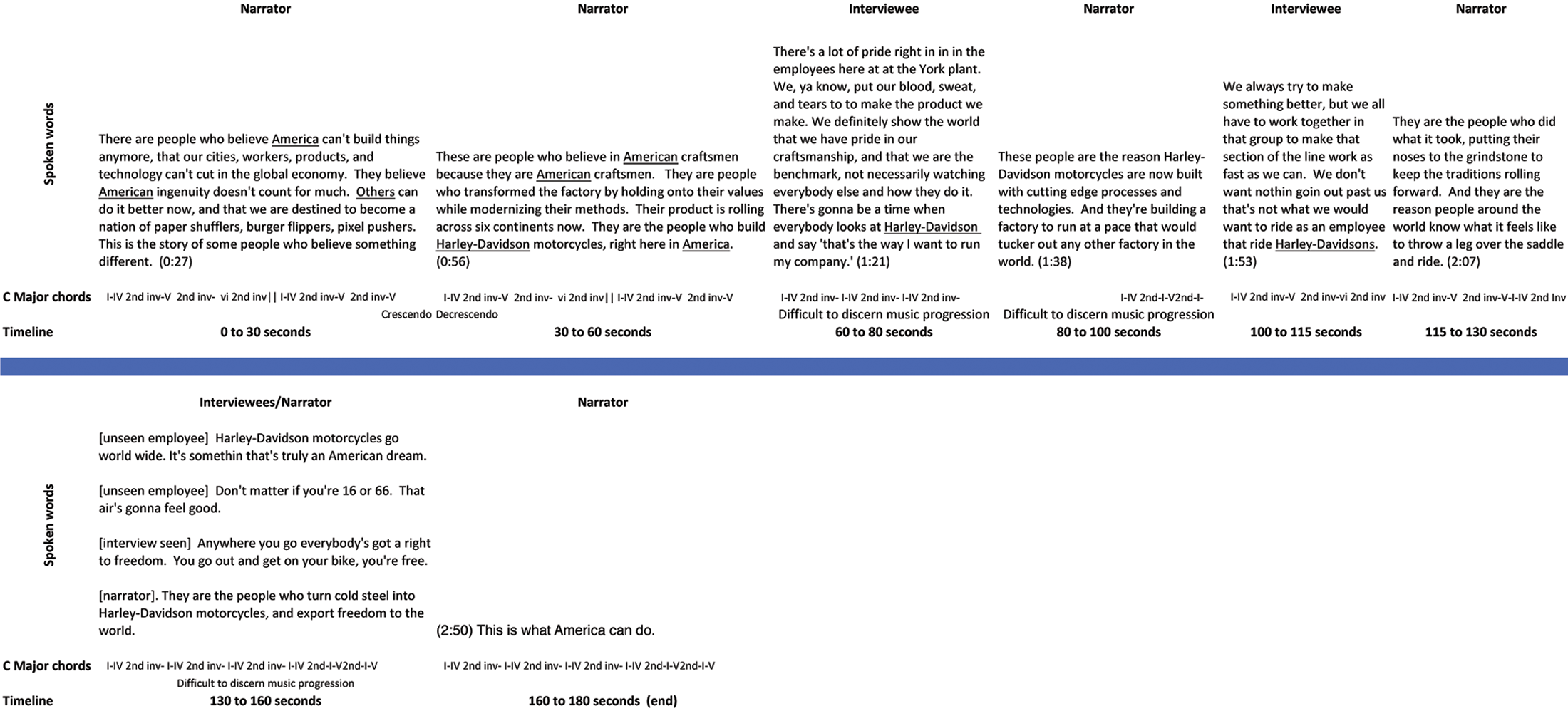

In addition to the signs depicted in figure 1, there is a soundtrack, which I have endeavored to map out in figure 2. The soundtrack includes a series of chords, forming musical progressions, apparently played on a synthesizer.Footnote 3 There is as well a synthetic rhythm and beat. Both chord progressions and rhythm/beat are more prominent in some phases of the video than in others. The soundtrack also consists of spoken words, both by a narrator and by several factory employees.

Figure 2. Timeline of the soundtrack, spoken words and music

Narration in the opening segment centers around a supposed put-down of America: “There are people who believe America can’t build things anymore, that our cities, workers, products, and technology can’t cut it in the global economy.” The narrator states that these critics believe “we are destined to become a nation of paper shufflers, burger flippers, pixel pushers.” Interestingly, this tack draws directly on a speech made by President Ronald Reagan at this very facility in 1987: “Some said that you couldn’t make the grade. They said you couldn’t keep up with foreign competition. They said that Harley-Davidson was running out of gas and sputtering to a stop.”Footnote 4 When shown an excerpt of the Reagan speech after the Harley-Davidson York Transformation video, interviewees had no difficulty grasping the continuity in rhetorical strategy here. As mentioned earlier, many of the constituent condensation symbols within the video, such as the American flag, the Harley-Davidson logo, the eagle, and so forth have considerable time depth, even if the video itself is a new bit of culture, constructed out of these older threads.

In his speech, Reagan goes on to counter the critics: “Well, the people who say that American workers and American companies can’t compete are making one of the oldest mistakes in the world. They are betting against America itself, and that’s one bet no one will ever win. Like America, Harley is back and standing tall.” The narrator of the Harley-Davidson video too counters the critics: “This is the story of some people who believe something different.” While the narrator is speaking, a sequence of ascending chords is present in the background, reaching its peak at this point along with a crescendo in volume. There is no other point in the video at which the music plays such a prominent role. Indeed, at some points in the subsequent video the volume is too low to enable one to pick out the chords.

Evidently, the intent of this first segment is to summon competitive feelings, in this case about America and American workers, but also about Harley-Davidson. The occasion for Reagan’s 1987 speech was the survival of Harley, thanks to a government bailout, in the face of intense competition from the Japanese motorcycle industry beginning in the 1960s. The company was forced then, as in the recent period, to restructure in order to survive. And it was one of the uplifting success stories. The video draws on this earlier success.

The narrator goes on to say: “These are people who believe in American craftsmen because they are American craftsmen. They are people who transformed the factory by holding onto their values while modernizing their methods. Their product is rolling across six continents now. They are the people who build Harley-Davidson motorcycles, right here in America.” So the story here is an “indexical icon,” summoning feelings surrounding past underdog stories and bringing them to bear on the present representations of the Harley-Davidson York facility. As in the other semiotic machinery discussed earlier, the words and music at this point form the sensory-orectic pole of the video as symbol. They help to charge this symbol with affective significance.

The narrative then shifts to the workplace, as we listen to interviews with workers interspersed with narrator commentary. The first worker says: “We, ya know, put our blood, sweat, and tears to make the product we make.” He goes on to predict the triumph of the underdog: “There’s gonna be a time when everybody looks at Harley-Davidson and says ‘that’s the way I want to run my company.’” The narrator reinforces the underdog triumph: “They’re building a factory to run at a pace that would tucker out any other factory in the world.” This is a narrative whose general outlines Americans have heard many times in connection with sports and also with war.

After emphasizing the hard work and teamwork ethic that enables this success, the narrative introduces the theme of freedom. Riding Harley-Davidson motorcycles, the workers themselves say, gives you the experience of freedom, makes you free: “Anywhere you go everybody’s got a right to freedom. You go out and get on your bike, you’re free.” The final segments then, after the rapid-fire montage of stills giving a sense of speed, concerns the export of freedom to the world, with shots of the motorcycles rolling off the assembly line and the names of destinations for those motorcycles appearing: California, Saudi Arabia, Michigan, Russia, China. The narrator then tells us: “This is what America can do.” As in the constituent symbols discussed earlier, the effect is to produce a transference of affectual quality, imbuing the Harley-Davidson company and its workers and products with feelings surrounding freedom and the role of America as a proponent of freedom in the world.

A last component of the structure of the video as a dominant symbol is shot frequency, whose manipulation for emotional intensification purposes has long been known to filmmakers. In film-editing circles, shot frequency is known as “pace.”Footnote 5 Figure 3 graphs the shot frequency over time measured by shots, where an individual shot is one continuous take of the camera. The shots in general last longer than a second, with the average shot lasting 2.07 seconds, translating into a rate of .48 shots per second. As the rate increases, the palpable emotional intensity tends to increase, with heightened visual saliency. Action sequences in movies regularly make use of this technique. However, moviemakers in general understand that they cannot simply increase intensity linearly. They instead alternate periods of intensity with lulls, so that the intensity can be better experienced. At the same time, if the video is to cull emotion, the trend of frequency has to increase over time. This is precisely what we see in the case of the Harley-Davidson video.

Figure 3. Shot frequency graphed over time, showing the general trend toward intensification (affect summoning), with ups and downs, reaching a climax with a de-intensification at the end.

In figure 3, I have not included the rapid-fire montage of stills, which occurs at the climactic moment when the export of freedom to the world sequence is about to begin. The individual “shots” (stills) occur at such a rate that the rest of the graph would appear to be flattened, with exception of that one high peak.

The formal analysis in all three of these figures reveals an overall transformative structure, which, when successful, produces a transference of affective qualities from images of small town America, craftsmen, and freedom to images and representations of the Harley-Davidson corporation, and, in particular, its York, Pennsylvania, facility. The overall structure is tripartite, the first part pertaining primarily to America and small town USA, with emphasis on the underdog. The second part pertains to the Harley-Davidson York manufacturing facility and its workers and products. The final part brings together Harley-Davidson and American representations with references to freedom and exporting freedom to the world. The video thus appears in its formal structure to be designed to call forth feelings toward America and community, and to imbue the Harley-Davidson facility and company with those feelings. In this sense, the structure resembles that described by Turner for the Ndembu mudyi or milk tree.

Significant Contexts in Which the Symbol Occurs

Turner observed that the milk tree—whose affective associational meaning pertains to breast-feeding, nurturance, togetherness, and community—occurs in a ceremony in which daughters are being separated from their mothers. This is therefore a time of conflict and sadness, as the young girls are growing up and leaving home. So the symbolism calls up sentiments of togetherness and community to overcome the internal divisiveness of life cyclic domestic group processes, to suture wounds, and to rebuild the collectivity.

There is an analogy here to the Harley-Davidson video. The latter was produced at a time of extraordinary conflict at the York facility. The Harley-Davidson company originated in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1903. It is still headquartered there. Motorcycle production today is still carried out in Wisconsin as well as in plants in Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri, in addition to the York, Pennsylvania, facility. However, in 1973, when the York facility was opened, all assembly operations had been moved to that site.

Fast forward to the Great Recession that began in 2008. By 2009, with company profits plummeting, Harley-Davidson management considered relocating the York facility to other parts of the country. After concessions from workers, the company decided to stay in York but to raze the old facility opened in 1973 and build a new, state-of-the-art plant. All of this was done over a two-year period, during which the York facility continued to produce motorcycles. The “Harley-Davidson York Transformation” video was created at the end of this period.

The transformation caused turmoil, with some employees losing jobs and others taking cuts in pay and benefits: “The first few months of the York transformation were filled with angst as people lost their jobs, casual employees were brought in, and the plant scrapped old ways of doing things” (Barrett Reference Barrett2012). According to one twenty-three-year York employee: “This whole company used to be family. It’s not that way anymore” (Barrett Reference Barrett2012). The plant manager, Ed Magee, likened the transformation to having “open-heart surgery as we were running the marathon” (Hagerty Reference Hagerty2012).

I should emphasize that I have not yet been given authorization to interview those who produced the video, although I have been able to gather that the plant manager, Ed Magee, was a driving force behind its creation. Based on an analysis of the objective characteristics of the video as symbol, however, and the context in which it was produced and disseminated, it seems reasonable (if not inescapable) to conclude that the video was designed to produce a sense of community and positive feelings about the York transformation, in the midst of upheaval and turmoil.

In this regard, the video seems to be intended to play a role analogous to that of the milk tree among the Ndembu. Whether the video can actually transmute the negative feelings of former or even current employees into positive sentiments toward the Harley-Davidson company is doubtful. But it is also doubtful that the milk tree does that for the mothers and daughters directly affected by the initiation ceremonies. The Ndembu ceremony rather affirms a broader sense of community in the larger group as a whole. It is the broader sense of community that helps those suffering to endure. Something like this, I contend, happens in the case of the video, although as I have been repeatedly noting, the Harley-Davidson video evokes negative as well as positive affect. It acts as a sorting force within a broader space, to whose exploration through interview data I now turn.

Affective Response to the Symbol

The method used here to explore semiotic uptake was to show the video to a range of interviewees and elicit their feelings and reactions immediately after viewing. While I conducted a number of the interviews myself, other interviewers, whom I recruited for this project, did the bulk of them. My analysis focuses on features of the dominant symbol and the verbal responses to them, especially when the commentary is spontaneous on the part of the interviewee, not elicited by the interviewer. There are obviously limits to which awareness can be achieved. For example, none of the interviewees to date remarked on the shot frequency variation, although someone with training in filmmaking would undoubtedly be aware of shot frequency as a manipulable variable. Indeed, almost any perceptible feature can become the focus of conscious reflection. Despite the difficulties in interpretation, I do believe it is possible to assess affective response from the interview data.

The components of the video that tend to come up in spontaneous, unprompted reactions of interviewees are principally the following:

People shown

American symbolism

Freedom

Small town America

Motorcycles in general

Harley-Davidson riders

Underdog representation

Music

Narrator’s voice

Aesthetics of the overall video

An interview with Katherine, a white upper-middle-class female from the northeast United States in her late teens, reveals her spontaneous responses to the video, with her affective orientation evident. When she was pressed by the interviewer, an older male I willl call Henry, about the narrator’s claim that some people feel American workers cannot compete on the global scene, she resists this competitiveness interpretation in favor of the warm feelings the video kindles in her generally about America and the small town life the video depicts:

Henry But they were also saying something about how people believe America can’t cut it anymore.

Katherine Um,

Henry Did you hear that part?

Katherine Yeah, I did hear that part, but um I don’t know I feel like that … it wasn’t as connected to the video. I was like watching the video: “hey, that looks like where I live or just down the street.” Then, when they say that, that’s not necessarily in tandem with the video, I think, so much as it is with what’s coming up where they say “we believe … we are a people who believe differently” or whatever they said. Because that’s when they’re saying, all like cause, what I think that they’re saying is: the people from the small towns they, they do believe in America. Like that’s what I think. I mean like most of the people I know believe in America um, and so I think when they’re saying we believe in America, yeah you believe in it too, and we believe in it and so there’s this sense of like togetherness because everyone believes in it.

Earlier, while watching the video, she spontaneously commented on the imagery:

Katherine [Spontaneously, while watching the first part of the video] Yeah, well they’re just showing like small town America. And like trucks … none of that stuff had anything to do with motorcycles. It was just like houses and trucks and streets and just what it’s like living in small town America.

Katherine [Spontaneously, while watching a later part of the video] And they also make the factory seem like a really nice place, like everyone who’s working there looks, looks friendly and nice, and the factory looks like a place you wouldn’t mind being, and so it looks like a good place. It just doesn’t seem like what you normally think of as a factory when you hear like women working in factories in other countries. It’s totally not that.

Katherine, like other interviewees, responded to the imagery in the video in terms of her own background. Her experiences of small town life, of America and its flag are all positive. Consequently, the video summons good feelings in her. Those feelings in turn imbue the factory scenes with positive affect.Footnote 6

In fact, Katherine’s responses were not much different from my own. She enjoyed the experience of watching the video, just as I had. Like me, she found the video to be well done, and—to get to my central point—she found it interesting or engaging. The video attracted her attention, exerted a kind of force, the force of interest.

The attractiveness, in her case, appears to be grounded in (1) the iconic association of the imagery with imagery from Katherine’s own experiences; (2) the fact that her own experiences of small town life and America are positive, filled with warm happy feelings, which the iconic association indexically kindles in her; and (3) her interpretation of the factory imagery, sequentially connected in the video to the imagery of small town life, as associated with the same positive feelings as the latter. In addition, there is (4) the artistic poetic structure of the video.

Katherine had no prior experience with factories or factory life, and the images she did have, as she mentions, were derived from reports of sweatshop conditions in foreign countries. Insofar as she had a view of factories, that view was negative. The video’s imagery was thus able to overcome the prior negative feelings and transmit to her a positive image of the Harley-Davidson York manufacturing facility, just as Turner had imagined for the mudyi tree.

As Henry attempts to bring closure to the interview, the following interchange occurs:

Henry Okay, that’s great. Have anything else you want to add?

Katherine Uuuuum I don’t know, again I, I can’t stress enough, it’s really that they have that they show all the people that work there, that they show the factory so much, because that’s really what will turn you on to this company is how what a good place it is. How “yeah, I would want to work there. I think that’s really cool.”

With responses like Katherine’s, I was coming to see the video in the way that Turner understood the Ndembu mudyi tree, as kindling positive feelings about the collectivity, as suturing the rifts in society, healing the wounds. However, other interviews quickly disabused me of the notion that responses to the video would be uniform. A twenty-something South Korean woman, whom I will call Ji-woo, for example, responded to the interviewer, an older American male whom I will call Owen, as follows, immediately after watching the video:

Owen So do you want to see any of it again or are you good?

Ji-woo Um I’m good and I think … I think like it’s it’s really American, American, American. [Intonation and rapidity of delivery indicating disapproval]

Owen American, American, American? Okay,

Ji-woo Yeah, that’s what I thought. Even though they say like how Harley-Davidson is international, and they show that the several different nation including China or Russia, it’s basically, um, no, all the guys who were working are mainly white middle-aged men.

Ji-woo was by no means alone in her negative reaction to the Americanism or the predominance of white males. In contrast to Katherine, who positively identifies with the video’s message, Ji-woo seems to disidentify. In a different interview (conducted by Conrad, an older white American male), with a thirtyish Japanese woman whom I will call Izumi, the white males are related to a negative stereotype:

Conrad So when you saw the people that were in the video, you didn’t identify with them and say …

Izumi Yeah they, they are, they are working hard, and they might be good people but, uh I don’t know, so

Conrad Did you feel like they were good people or not? You couldn’t tell?

Izumi I don’t know, I couldn’t tell. I just felt they are working and they says they say uh uh because because most of them is white. I, I think it’s my stereotype of Harley-Davidson and that kind of people, you know the blond hair and white and beard.

Conrad beard …

Izumi Yeah and we, you know, we have some kind of stereotype against that guy.

Conrad You have them against that guy?

Izumi Not against. We have some … as an Asian and foreigner I have a uh vague fear uh about that guy.

Conrad Oh fear

Izumi Yeah because they might hate me.

By evoking a not-me stranger response, in Izumi’s case, the video taps into fears related to threats to self. As with Katherine, there is iconic association, but for her the images call forth a negative stereotype—people who “might hate me.” Her emphatic response suggests a powerful feeling, and a decidedly negative one, the feeling of being the object of another’s hatred. The symbolic force, in this case, is to transmit not a positive attitude toward the Harley-Davidson company and its York facility and workers, but rather a negative one. The symbol induced a “not-me” experience. Izumi disidentified with its imagery, which kindled bad feelings. These bad feelings in turn imbued the Harley-Davidson factory and company with bad feelings.

If Katherine had vaguely negative images of factories before seeing the video, the video nevertheless overcame those images and replaced them with positive ones. This is how Turner imagined the mudyi tree to operate as a symbol. It was community building. The same did not happen in Izumi’s case. If anything, the video confirmed or intensified whatever prior negative feelings she had about the Harley-Davidson company. The symbolic force, in this case, was repulsive.

Other interviews confirm this gatekeeper function of the video as symbol, as if it were, as I suggested, Maxwell’s demon, counteracting the force of entropy. Jack, a New Zealander in his late twenties, speaking with Adam, an older male interviewer, stopped the video, as he was watching it, to spontaneously comment on the underdog view of America:

Jack It’s kind of a straw man beginning. I’ve never actually heard anyone say any of those things.

Adam Oh okay so straw man in the sense of …

Jack Straw man in the sense of setting up people who say that Americans— America can’t do x, y, z. But maybe such people exist but I’ve never …

Adam You’ve never heard them. Ok, alright, alright

Jack Even Canadians never say such a thing.

Adam Yeah I think you can just press the space bar.

Many others, even when prompted, seemed not to notice the underdog representation, or to see it in light of the later positive, can-do theme. As discussed, Katherine found the underdog theme to be out of keeping with the video as a whole.

Jack, however, whose attitude toward the underdog story was negative, singled out, again spontaneously, the use of the word “freedom,” which he also disliked:

Adam Well there you have it. [Laughs] So your response?

Jack Uhh um

Adam Firstly did you like it, I guess?

Jack Uh it got sort of kookier as it went along.

Adam It got kookier, okay.

Jack I thought it was good initially but then the equation of freedom with the production of, not only the production of Harley Davidsons but the selling of Harley-Davidsons in Saudi Arabia, say, seemed a little strange to me. I am not sure that’s the understanding of freedom that operates in Saudi Arabia for example. But um I thought it looked good. I appreciated the shininess of the steel and the discussion of the steel and things but just the equation of the physical product with just this kind of uh slightly far-fetched things it was supposed to represent at the end seemed a little odd. And then the business of no cages … I wasn’t sure if that was a kind of … what that was referring to. [Mumbles]

Unlike Izumi, and a number of the others who reacted negatively to the predominantly white male figures in the video, Jack seemed neutral, but again spontaneously pointed to the use of the word “freedom” as the aspect of the video he found objectionable:

Adam Okay, did you like the people?

Jack Um again, initially when they were talking up the steel and making a hunk of steel into a Harley Davidson I thought they were more likeable than when they were talking about the air cages and the exportation of freedom

Adam Could you envision them as people that you might know or that might be relatives of yours or …?

Jack Um I don’t see why not.

Negative responses are not, by any stretch, confined to non-Americans. The American symbolism rankles many American interviewees, especially highly educated ones from elite institutions. Richard, for example, a late-twenties upper-middle-class highly educated white male from the northeastern United States, spontaneously made the following remarks at different points in the interview:

I kind of rolled my eyes a little bit …

this hoorah American spirit. [with disdainful emphasis]

It seemed like it was laying it on a little thick.

Like Izumi, Richard strongly disidentified with the people in the video. However, unlike Izumi, his disidentification seemed to stem from disdain rather than fear:

It definitely seems like there was a division between the people I would probably hang out with …

Still, even Richard saw positive aspects to the video:

The flow of the video was very good. I really liked the segment where they’re piecing together the Harley …

It is intriguing that many of the interviewees failed to comment on the music, and, indeed, some seemed not to be aware that the video contained music at all, while for others the music made a critical contribution. Katherine, for example, spontaneously brings up the music when Henry tries to focus her attention on the underdog representation:

Henry So the very beginning part didn’t make you feel like that the people were underdogs, and so they were going to triumph over adversity.

Katherine That’s not really what I got from it, but I did think that the music um kind of had that feeling. It was the, the music that they play when the team who’s the underdog is walking out onto the field and in slow motion and it, it was building and it’s definitely it, it gave you a good feeling. It left you like feeling empowered like someone was giving you a pump you up speech.

In a similar vein, MaryLou, a middle-aged white woman raised in the southern United States, responded to a prompt about patriotism from Ann, a young white female interviewer, and in the course of her response to the prompt spontaneously refocused on the music:

Ann And so you, you talk about the patriotism um how did you feel as an American watching this, as far as patriotism goes?

MaryLou Oh the uh the um the pride, the sense of pride to be an American. I loved his voice whoever they had do the reading, and the key points that they brought out with being an American um, I think that was a good aspect that they didn’t necessarily ask people to speak that had proper English or that were very well spoken but what they had to say was from the heart. It, it sounded like it was from the heart, as opposed to someone that spoke very well and had rehearsed it um um I thought that was different but definitely that sense of pride being an American.

Ann So did you feel a sense of pride yourself?

MaryLou Definitely absolutely.

Ann And so you kinda thought of this as a positive

MaryLou And and the music as well

Ann the music

MaryLou You always felt like you were building up to something positive

Ann mmm

MaryLou I think they did a great job with the choice of the music as well. And the pictures they showed and seeing the American flag, homes that people live in, small town America, Main Street in small town America as opposed the big city, you know, downtown, so that it gave you that old fashioned American … [tapers off]

When I discussed the video with students and faculty during a presentation at the Peabody Conservatory of the Johns Hopkins University, many in the audience immediately focused on the music, as one might anticipate. Some of the comments were positive in a backhanded way, suggesting that the synthesizer soundtrack might be good as a neutral symbol, because the musical tastes among Harley riders are diverse and choosing a genre that would appeal to one group could alienate other groups.

Although I have not endeavored to map out anything resembling a “social space” of responses, in Bourdieu’s (Reference Bourdieu and Nice[1975] 1984) sense, it is evident that the gatekeeper function of the symbol, through kindling in different individuals opposed feelings, marks social distinctions. Responses are, no doubt, conditioned by prior habitus, as Bourdieu would predict. In Bourdieu’s scheme, the habitus is a disposition acquired earlier to respond in specific ways to new experiences. The disposition idea would suggest that a dominant symbol, like the mudyi tree or the Harley-Davidson York Transformation video, has only a presupposing indexical effect. Like a Pavlovian stimulus, the subject responds in a determinate way, based on prior conditioning.

Turner’s proposition, as well as the one I have put forth here, suggests that the indexical effect of a complex symbol is not only presupposing—with responses to the symbol being conditioned by past experience in a Pavlovian sense; rather, the symbol is also creatively indexical, bringing into existence and entailing something that was not there before (Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Boas and Selby1976, 33–35).

In the case of the Harley-Davidson video, the affective response may operate in the Pavlovian fashion. However, if I am correct, for at least some persons, the symbol is also capable of bringing about something new—an orientation or a new orientation to the Harley-Davidson company and York manufacturing facility. Although Katherine, for example, had thought of factories in a vaguely negative light, as sweatshops, the video changed her view, at least as regards the Harley-Davidson York manufacturing facility. We have no way of knowing whether the change will be lasting, but hers is an example of a change.

How is such a change accomplished? I have argued that the change is a result of cultural motion. An aspect of culture—an orientation to the Harley-Davidson Company and an affective association with that company—makes its way from the physical symbol into the individual. The Harley-Davidson video, as a dominant symbol, is structured in the tripartite fashion depicted in figure 1. The first part culls affect through iconic indexical associations with prior images—small town America, the American flag, Main Street. But it does not stop there. If it did, it would be operating in Bourdieuian fashion as an indexical responded to in accord with prior dispositions.

What the symbol does additionally is create an indexical linkage, based on temporal contiguity within the timeline of the video between those opening images and their corresponding associations, on the one hand, and images of the Harley-Davidson plant, including logos, people, motorcycles, and words, on the other. This linkage is what, if successful, brings about a transference of affectual quality, an affective orientation or a new affective orientation to the Harley-Davidson company. The third part of the video brings those two sets of images together, attempting to fuse them into one.

I have proposed further that this movement from the symbol into the individual requires a kind of force. The force I have proposed in particular is interest. If the movement is to take place, the symbol has to awaken interest in the individual. It must be sufficiently alluring that the individual records at some level the proposed new connection. This, of course, depends not just on the iconic indexical associations with specific constituent symbols (shots of the American flag, for instance) within the larger symbol. It depends also on the aesthetic coherence of the entire complex condensation symbol, which, I have argued, is provided in part by the overall tripartite structure.

While the interview data indicate that individuals have different responses to the imagery, so that the symbol is capable of producing opposed effects, the data also suggest that most people responded positively to the aesthetics. Jack, for example, while critical of the underdog theme and the use of the word “freedom,” nevertheless conceded at various points that the video was in some ways aesthetically satisfying to him:

Jack I thought it looked good. I appreciated the shininess of the steel and the discussion of the steel and things …

The same is true of Richard, who looked disdainfully on the “hoorah American spirit” and was otherwise skeptical about the videos message:

Richard The flow of the video was very good.

Richard I really liked the segment where they’re piecing together the Harley …

Only one extended interview expressed a consistently critical attitude toward the video, finding in it seemingly no redeeming interest. When interviewed by Clifford, an American academic, Natalia, a mid-twenties college graduate from Venezuela had this to say:

Clifford So that’s the video. So I guess the first question is did you like it or dislike it or no feelings at all about it?

Natalia Um kind of long

Clifford Too long?

Natalia Yeah

Clifford Do you think it should have been edited down?

Natalia Yeah much shorter. Um I guess you can see where it’s going since the beginning.

Clifford What-how-where is that?

Natalia Uh well like an American product and it will give you the American experience in time of crisis or something like that. Um the guys are kind of funny and they are not consistent with the narrator.

Clifford Oh okay. Tell me what you thought about that.

Natalia So um they are kind of you know they have the glasses and the sort of Southern accents and then there’s this very sort of God-like voice or whatever you call that narrator who is …

Clifford Omniscient narrator.

Natalia Yeah who is very you know eloquent and not a worker but something like that. Um what else? They were kind of funny looking, sort of grungy fat men. And then the last part is pretty bad about exporting freedom.

Clifford What’s bad about that?

Natalia Uh its just silly and then the countries that they picked like China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia are just sort of odd selections for places to export freedom in the shape of a motorcycle I guess.

Clifford So the grungy guys that you mentioned. Tell me more about what your interpretation of them [is].

Natalia Okay well they were wearing sunglasses and particularly the second one had a funny beard that was strange.

Clifford What was your feeling about them? Like …

Natalia Yeah I don’t know if they are supposed to be workers in the factory or sort of users of Harley Davidson but it seems like they’re supposed to be both which is why they look like they could be workers in Harley Davidson but also they could afford the machine.

Clifford They could afford it?

Natalia Yeah

Clifford So it looks like they earn enough money to be riding—

Natalia A Harley Davidson yeah or maybe they are so passionate about Harley Davidson that if they didn’t have enough money they would still buy one.

Clifford And what kind of person does that? I mean they look like the kind of person but how would you characterize that?

Natalia Well there is a certain aesthetic about motorcycle riders, especially Harley Davidson. Ah well I guess its their brand. It’s well sold but um the leather jackets and the beard and tattoos and piercings sort of yeah 90s leather look.

Clifford 90s leather look.

Natalia Yeah

Clifford Okay, that’s good. And I’m gathering that maybe you don’t have a very positive image of those people. Is that right?

Natalia Well it’s not positive or negative but it’s certainly not my niche.

Clifford It’s not your niche.

Natalia No

Clifford Okay yeah so you don’t identify with any of the guys?

Natalia No I would never buy a Harley Davidson. So it’s like seeing a commercial which is fun; well it’s not fun; it’s very boring and long but I still I would never even consider switching sides. Or being with someone who is into Harley Davidson.

Natalia is, evidently, a sophisticated aesthetic critic, and this extended excerpt from the interview sums up many of the points I have been making—her disidentification with the people depicted in the video, dislike of the export of freedom theme, dislike of Harley-Davidson, and even the narrator’s voice. Only at one point did she make a positive comment, referring to seeing the video as “fun,” but then she corrected herself: “well it’s not fun; it’s very boring and long.”

Natalia evinces no aesthetic satisfaction in viewing the video. Her words suggest rather a thoroughgoing repulsion from the video as condensation symbol. In this, she contrasts with MaryLou, who found something to praise in each aspect of the video on which she commented. MaryLou used no negative words, seemingly finding every aspect of the video attractive. These two represent, within the interview set, the polar contrasts between repulsion and attraction. The other interviewees ranged between these extremes. Natalia’s disdain, for example, resembles that of Richard—the highly educated individual from the northeastern United States who used the phrase “this hoorah American spirit” to describe the video. However, not even Richard was so uniformly critical in his orientation. His occasional positive remarks suggest that he took satisfaction from some aspects of the video. Correspondingly, Katherine’s responses come closer to those of MaryLou, although Katherine was less admiring, more analytic in her awareness of and appreciation for the video’s techniques. Yet like MaryLou and unlike Natalia, she reports aesthetic satisfaction in watching the video. The interviews thus make apparent differing responses to the complex condensation symbol and its constituent signs.

Conclusion

My purpose in this essay has been to break open one “dominant symbol,” in Victor Turner’s sense, in order to see what lies inside and so to better understand how it works. In revealing the internal semiotics of the Harley-Davidson York Transformation video, my goal is to shed light on the concept of “symbolic force” proposed by Turner, a notion having roots in Durkheim’s idea of a “totemic force” or “religious force.” Both conceptions, I have suggested, speak to issues in the recent anthropological literature on branding, especially that concerned with brand as fetish.

Symbolic force, I contend further, needs to be studied from the perspective of cultural motion—how and why something contained within the symbol as objective form makes its way into individuals and groups. Symbolic force can be understood in terms of the types of forces that affect cultural motion more generally: inertia, entropy, interest, and metaculture. I have suggested that the dominant force in the case of the Harley-Davidson video is interest, the force of attraction to and repulsion from culture.

While I have grouped together Turner’s and Durkheim’s notions of force, I actually regard them as distinct. Durkheim was most concerned with the authority of the totem and of religion more generally. For him, the force is the feeling individuals have that they must obey, for example, by carrying out the rites associated with the totems. In my view, authority involves predominantly metacultural force, although interest is almost certainly at work as well, along with inertia.

Interest comes to the fore to a greater extent in Turner’s account of symbolic force—with the association between the mudyi’s milky sap and mother’s breast milk. However, inertia and metaculture, in the form of traditional practice and expert teaching, likely play a much greater role here than in the case of the Harley-Davidson video, which relies more heavily on interest as the motive force—the force that causes the cultural orientation embodied in the video to be transmitted and then taken up (or rejected) by viewers.

If transference of affectual quality does take place, the question is how to demonstrate it through empirical investigation. My suggestion is that interview data can reveal whether and also how the uptake (or rejection) takes place. Using not only the denotational text of the interview, but also the interactional text (Silverstein and Urban Reference Silverstein, Urban, Silverstein and Urban1996, 4–6), including paralinguistic features, it is possible to reach a reasonable degree of assurance about the uptake or rejection—in the present instance, uptake being the association of the Harley-Davidson company and its York manufacturing facility with the imagery and affective associations of small town American life, the flag, and ideas of freedom.

While response to the latter is conditioned by habitus, in Bourdieu’s sense, and past experience, I have proposed that the dominant symbol is capable in some measure of effecting change, as Turner argued for the Ndembu mudyi tree. Because the video, like dominant symbols generally, is a complex sign, consisting of many constituent signs, it is able to create associations among the signs that are not part of the prior experience of the individual. In particular, in the Harley case it is able to attach, for at least some people, the feelings toward small town life, America, the flag, and freedom to the Harley-Davidson company. When it is successful, it transmits those connections to viewers.

At the same time, the interviews reveal that habitus does matter, that what acts as an attractive force for some can be repulsive for others. This leads us to view the symbolic force as exercising a gate-keeping function, helping to create and maintain distinctions within a social space. In this way, the symbol behaves like Maxwell’s demon, carrying out a sorting that counteracts the tendency toward randomness and disorder.

However, the general correlation between prior disposition and response should not obscure the active role of dominant symbols, like the Harley-Davidson video or the mudyi tree. Condensation symbols exert a force; they effect change in the world. They do so by transmitting an orientation to those who engage with them. In the version of force I have proposed, the orientation or attitude toward a collectivity—the Ndembu or the Harley-Davidson Company—gets transmitted from the symbol to the persons engaged with it. Symbolic force supplies the impetus for that transmission. It is thus but a special case of the forces that move culture more generally.

Nevertheless, it is a force worthy of further investigation. An analysis of the Harley-Davidson video shows that its efficacy depends on its complexity as a condensation symbol, consisting of many constituent signs. Some of those constituent signs are presupposing indexical icons, calling up emotions based on past associations (or prior dispositions, in Bourdieu’s sense). However, because of their contiguity with other constituent signs within the larger dominant symbol, they are able to attach those feelings or affective responses to new indexical icons, such as those related to the Harley-Davidson company and its York manufacturing facility. Those who interact with the symbol—the video in the Harley-Davidson case—may thereby acquire the new orientation to the collectivity from the symbol. The force that produces that transfer is the force of interest.