As the apostle who was credited with the authorship of the Fourth Gospel and Revelation, St John the Evangelist enjoyed widespread veneration throughout the Christian realm. In the medieval diocese of Liège his cult attracted special attention, with two collegiate churches under his patronage. Present understanding of the Evangelist's liturgy at the collegiate church of Saint-Jean in the city of Liège is obscured by the loss of all medieval service books for this institution, yet liturgical evidence of the saint's local importance has survived for the church of Sint-Jan in the town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch located on the diocese's northern frontier. Significantly, the clergy of Sint-Jan venerated their titular patron with as many as five high-ranking annual feasts,Footnote 1 two of which are unknown outside of the diocese – John's Exile on the Island of Patmos (27 September, displacing the feast of Cosmas and Damian, which was moved to the following day) and Return from Exile (3 December, the vigil of St Barbara).Footnote 2

Although Patmos was pictured prominently in the Western iconography of John's prophetic vision and writing of the Apocalypse,Footnote 3 as seen for example in the panel St John on Patmos by Hieronymus Bosch (Figure 1) depicting John's vision of the woman clothed with the sun (Revelation 12:1), the circumstance of John's exile constituted but a minor episode in the saint's life. One of the most familiar accounts – the fifth-century Passio Iohannis, itself a source for the widely disseminated Golden Legend attributed to Jacobus de Voragine (c.1260) – describes this event in a single sentence: ‘Thus it happened that St John was brought from Ephesus and sent into exile in the island of Patmos; it was in this island that he wrote in his own hand the Apocalypse which the Lord revealed to him.’Footnote 4 Influenced by the Passio Iohannis (one of the standard sources for the readings on John's principal feast observed universally on 27 December), the Western liturgy proper to St John gave only cursory attention to his exile.Footnote 5 In the modally ordered series of Matins antiphons sung widely throughout medieval and early modern Europe, including ‘s-Hertogenbosch (see Table 1), only two from the second nocturn are thematically relevant: the fifth antiphon Propter insuperabilem, in which the exiled John is consoled by a divine vision and spoken message, followed by the sixth Occurrit beato Iohanni, in which John is welcomed back from exile with the acclamation ‘Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord’ (quoting Psalm 117).Footnote 6 The existence of two high-ranking feasts dedicated to John's exile in the ‘s-Hertogenbosch liturgy thus raises questions of means and motivation. How did the clergy of Sint-Jan embellish the standard Western liturgical narrative in sufficient detail? And, more fundamentally, why did they wish to do so?

Figure 1. Hieronymus Bosch, panel St John on Patmos, probably for a Marian altarpiece in the chapel of the Confraternity of Our Lady at Sint-Jan in ‘s-Hertogenbosch (c.1489). Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, 1647A.

Table 1. Office chants and readings for the feasts of the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium and Reversio Ioannis ab exilio

Note: ‘s-Hertogenbosch sources for these two feasts: #1 F-Pn RES B-7881 (unfoliated); #2 NL-SHsta 216-1, fols. 77r, 85v; #3 NL-DHk 68 A 1, fols. 90r–v, 142v–143v; #4 NL-Au I A 23, fols. 111v–112r, 194v–196r

aE = Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium

bR = Reversio Ioannis ab exilio

* Also prescribed in the Sint-Jan office for John's principal feast (27 December). Texts and melodies are preserved in #2 NL-SHsta 216-1, fols. 35v–36v; #3 NL-DHk 68 A 1, fols. 16r–20r; #4 NL-Au I A 23, fols. 17v–22r, 24r–v; #5 NL-SHbhic 149, fols. 3v–5r, 17r–26v; #6 NL-SHbhic 159, fols. 21r–22r; #7 NL-SHbhic 162, fols. 32r–36r

Drawing from an exhaustive study of all extant liturgical evidence, including a previously overlooked printed libellus, I present the first comparative analysis of the office chants and readings for John's Exile and Return.Footnote 7 These feasts invite comparison on account of their shared exilic theme and apocryphal source for the Matins readings, quoting from the Acts of John by Prochorus – a fifth-century narrative that circulated widely in Byzantium but remained obscure in the Latin West. Although Prochorus contradicts the Western prophetic association of Patmos by imagining this island as the locus for John's Gospel mission, the corresponding responsories synthesise Eastern and Western interpretations to celebrate John's status as both preacher and prophet – attributes that merge in the musical form and melodic embellishment of these previously unstudied chants. More broadly, this article demonstrates how different hagiographic narratives intersect in late medieval accretions to the office liturgy, especially through liturgical song.

Before proceeding, a brief overview of the Western medieval understanding of St John's authorship of the Fourth Gospel and Revelation will help to clarify details of word choice, both in the liturgical texts themselves and in my interpretation. Traditionally, John was identified as an evangelist in the Gospel and prophet in the Apocalypse,Footnote 8 as documented, for example, by the influential eleventh-century ascetic Peter Damian in one of his sermons for St John,Footnote 9 which circulated alongside Latin translations of the Acts of John by Prochorus (see Appendix 3). The contents of both biblical books were believed to have been revealed to John through visionary experience and were perceived to share a common source:Footnote 10 the secrets that John drank from Christ's breast at the Last Supper – referenced in the office chants for John's principal feast, such as the antiphon Supra pectus Domini and responsory Iste est Iohannes qui supra pectus. Yet the transmission of these heavenly mysteries differed: John initially preached his Gospel vision through speech alone but immediately transcribed his apocalyptic vision in writing.Footnote 11 As the following study aims to demonstrate, these distinctions converge in the ‘s-Hertogenbosch liturgy in unique ways.

Reconstructing the ‘s-Hertogenbosch Offices of St John's Exile on Patmos and Return from Exile

Late medieval ‘s-Hertogenbosch has long been recognised as a musical and artistic centre. Built on land belonging to Duke Henry I of Brabant (1165–1235), the church of Sint-Jan is first documented in 1222, not long after ‘s-Hertogenbosch received city privileges (c.1200).Footnote 12 In subsequent centuries, the church grew to include the prestigious and musically active Confraternity of Our Lady (founded in 1318),Footnote 13 a chapter of thirty canons (established by the bishop of Liège in 1366), and a parish (decreed by the pope in 1413). Sint-Jan fell under the jurisdiction of the cathedral of Liège until 1559, when ‘s-Hertogenbosch became the seat of an independent diocese. Despite enduring scholarly interest in the church's history and restoration, illustrious artwork – including the aforementioned panel by Hieronymus Bosch, a sworn member of the Marian confraternity – and polyphonic manuscripts prepared in the workshop of the famed music scribe Petrus Alamire, the local plainchant repertory has received relatively little attention.

The principal obstacle to musicological study of the ‘s-Hertogenbosch liturgy is the lack of an extant breviary, lectionary, ordinal and complete antiphoner. Previous studies by Jennifer Bloxam, Ike de Loos, Véronique Roelvink and Sarah Long have focused on the contents of the extant choirbooks copied for the chapter of Sint-Jan and its Marian confraternity (Appendix 1).Footnote 14 The sole surviving source of the office chants sung by the chapter of Sint-Jan is an intonation book for the cantor (NL-SHsta 216–1) copied by the Brethren of the Common Life in their scriptorium in ‘s-Hertogenbosch c.1500, consisting primarily of incipits and responsory verses for high-ranking feasts. Melodies matching the incipits for John's principal feast are found in four late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century choirbooks for the Confraternity of Our Lady (NL-SHbhic 149, 152, 159 and 162) and two sixteenth-century antiphoners for the Brethren (NL-DHk 68 A 1 and NL-Au I A 23).Footnote 15 None of these notated manuscripts, however, preserve the complete offices for St John's more localised observances.

Yet a previously overlooked printed source provides the missing pieces of this liturgical puzzle. A catalogue reference by Ike de Loos led me to a sixteenth-century liturgical imprint documenting precisely the liturgical practices that differ from those of the cathedral of Liège.Footnote 16 In the only extant copy, currently housed at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris (F-Pn RES B-7881), the winter and summer sections have variant titles: Festorum compositorum Ecclesie collegiate sancti Ioannis Apostoli & Euangeliste in Buscoducis (for the winter) and Festa composita siue peculiaria ecclesie collegiate sancti Ioannis apostoli & euangeliste in Buscoducis (for the summer).Footnote 17 This libellus was printed by the prolific publisher Michael Hillenius during his residence in Antwerp between 1506 and 1547, possibly c.1525. Rubrics specify that it was intended to supplement the more traditional service books following the use of the cathedral – perhaps previously printed copies of the breviary (1484, 1492, 1509–11) and missal (1509). Hillenius himself printed a copy of the cathedral ordinal in 1521, two copies of the breviary in 1535, and two copies of the missal in 1540.Footnote 18 Comparative tables at the beginning of the winter and summer sections reference the use of the cathedral ordinal (secundum Ordinarium Leodiensem) – could this be Hillenius's own 1521 copy? – and highlight differences in the rank of more common feasts as well as observances unique to ‘s-Hertogenbosch. The remainder of the book consists of rubrics, readings and texts of the chants for all localised practices including the five feasts of St John. By combining the texts of this printed source with the melodies of the aforementioned choirbooks, it is now possible to attempt to reconstruct the obscure Offices of John's Exile and Return (see Appendix 2).Footnote 19

Owing to the lack of local extant liturgical sources prior to c.1500, dating the feasts of St John's Exile and Return must remain conjectural.Footnote 20 Yet when we combine documented developments in the history and building of the church of Sint-Jan with extant evidence of the Western Latin transmission of the Acts of John by Prochorus (discussed at greater length later), the time frame narrows to roughly two hundred years, between the late thirteenth and late fifteenth centuries – with preference for the fifteenth century. Although the first extant documented reference to St John as the titular patron is from 1274 (establishing a likely terminus post quem), it is important to note that the land upon which the city emerged originally belonged to the domain of Orthen and its parish, St Saviour.Footnote 21 Since the parish clergy of Orthen retained oversight of Sint-Jan until it was decreed the sole civic parish in 1413, it is unlikely that the ‘s-Hertogenbosch clergy would have introduced liturgical accretions specific to their titular patron prior to this date. Indeed it was during the fifteenth century that the church of Sint-Jan underwent significant architectural and artistic renovation, with the completion of the rood-loft and its triumphal cross flanked by statues of the co-patrons the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist in 1445, an elaborate baptismal font depicting the Evangelist alongside the diocesan patron St Lambert in 1492, and the consecration of a new chapel co-dedicated to St John for the Marian confraternity in 1494 housing the altarpiece in which the aforementioned panel by Hieronymus Bosch was likely displayed.Footnote 22 It is also significant that fifteenth-century copies of the apocryphal Acts of John by Prochorus, as opposed to their thirteenth-century counterparts, provide the closest models for the Matins readings on both feasts.

The office liturgy for St John's Exile and Return borrows extensively from that of the Evangelist's principal feast (dies natalis) observed on 27 December (indicated by an asterisk in Table 1). Common to all three offices are the five versified, modally ordered antiphons and hymn at First Vespers celebrating John's status as a virgin and visionary, the modally ordered antiphons of Matins drawing from patristic and apocryphal sources to outline John's principal attributes and deeds, and the biblically derived antiphons of Lauds detailing John's privileged relationship with Christ followed by a hymn meditating on the divine source of John's Gospel vision and preaching. The ‘s-Hertogenbosch rite follows that of the cathedral of Liège in the antiphon series for Lauds, first documented in a ninth-century antiphoner from the Benedictine Abbey of Prüm, and in the antiphons for Matins, based on a tenth-century series that circulated widely in secular and monastic sources across Western Europe.Footnote 23 Less standard are the versified antiphons of First Vespers and the proper hymns for Vespers and Lauds.Footnote 24

In the ‘s-Hertogenbosch Offices of John's Exile and Return, the hagiographic narrative becomes increasingly complex in the readings and responsories of Matins. As discussed in greater detail later, the anonymous readings prescribed for Matins quote the same hagiographic source – a fifth-century text of Syrian origin called the Acts of John by Prochorus, attributed to the Evangelist's most loyal disciple.Footnote 25 This obscure text does not influence the responsories. In the Office of John's Exile (see the E column in Table 1), the first six responsories borrow from a widely disseminated series for John's dies natalis prescribed in ‘s-Hertogenbosch and in Liège based predominantly on Old and New Testament passages plus a homily by Bede,Footnote 26 followed by three responsories of unknown (local?) origin that are unique to this feast. In the Office of John's Return (see the R column), the responsories of the first nocturn borrow from those sung in ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the second nocturn on the octave of John's dies natalis and also in the third nocturn of his commemorative office. These same responsories were prescribed in Liège for the third nocturn of John's dies natalis and like those of the beginning of this series draw from the Bible and from Bede.Footnote 27 The Office of John's Return then shifts in the second nocturn to three responsories from the Common of Evangelists that describe Ezekiel's vision of the tetramorph followed in the third nocturn by another group of responsories that are unique.

Finally, at Vespers on both feasts the responsory and Magnificat antiphon differ from those prescribed for the dies natalis to reinforce the visionary basis for John's preaching and prophetic activities. Second Vespers concludes on both feasts with the same Magnificat antiphon, Ecce ego Ioannes, from the Common of Evangelists quoting John's own vision of the Four Living Creatures as recorded in Revelation.

With this overarching structure in mind, the most proper and unique elements of each office – the nine readings and concluding three responsories of Matins – merit more detailed examination. How did these readings based on Byzantine tradition reach late medieval ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and what story do they tell? And how do the concluding responsories enrich St John's local liturgy, both thematically and musically?

Matins readings from the Byzantine Acts of John by Prochorus

In the choice of readings at Matins on the feasts of John's Exile and Return, the ‘s-Hertogenbosch rite overlooks standard Western interpretations of the Evangelist's life and legends to favour an unusual source of Syrian origin: the Acts of John attributed to Prochorus.Footnote 28 Although this account of John's ministry and exile circulated widely in Byzantium and provided an authoritative basis for the life of the Evangelist in Byzantine hagiography, it was little known in the Latin West, with only eight documented manuscript copies dating from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century (see Appendix 3).Footnote 29 Historian Damien Kempf has identified the neighbouring diocese of Metz and specifically the Benedictine Abbey of St Arnulf – co-dedicated to St John the Evangelist in 1049 – as an important site for the Western transmission of the acts. Supporting his argument are the three copies (F-Pn lat. 5357, D-KNa 86 and the now lost Codex ‘Embricensis’) that also transmit legends of the abbey's supposed founder, Bishop Patiens of Metz, who was believed to have received his apostolic mission from St John.Footnote 30 As heard in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, however, the Matins readings most closely resemble a fifteenth-century copy (B-Lu 115) from the Liège scriptorium of the Crossed Friars (Croisiers) – a monastic order originating from within the diocese that followed the rule of St Augustine – and a similar copy (F-Pm 4318) destined for the Carthusians of Hérinnes near Lille in the neighbouring diocese of Cambrai.Footnote 31 The transmission of the Acts by Prochorus among the Crossed Friars and the Carthusians is significant, for in late fifteenth-century ‘s-Hertogenbosch, local communities of these monastic orders shared documented connections to the secular clergy of Sint-Jan.Footnote 32

The readings proper to the feast of John's Exile focus on the Evangelist's sea journey to the island of Patmos (see Appendix 4).Footnote 33 Having been banished from Ephesus for having allegedly insulted the pagan gods (Lectio 1), John is bound in chains (Lectio 2) and forced, alongside his disciple Prochorus, onto a ship (Lectio 3) where they are given meagre rations of bread, water and vinegar (Lectio 4). During the journey, one of the Ephesian soldiers falls overboard (Lectio 5) and when his associates beg John to assist them, John asks them why their gods cannot help (Lectio 6). John then holds up his chains and commands that the soldier be returned unharmed (Lectio 7). After a huge wave drops him at John's feet, the Ephesians praise the Lord and release John from captivity (Lectio 8). Once on Patmos, the Ephesians remain with John and Prochorus for ten days then depart rejoicing, having received a blessing (Lectio 9).

When heard against the Western association of Patmos as a secluded revelatory site,Footnote 34 this Eastern emphasis on John's ongoing evangelising mission may have been surprising. Following the miraculous triumph of Christianity over paganism during the sea journey, John continues his ministry by blessing – possibly baptising – the new converts.Footnote 35 As heard in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, this unusual narrative would continue in the readings proper to the feast of John's Return, which give even more emphasis to John's preaching.

The ‘s-Hertogenbosch readings for the Return combine the standard Western depiction of Patmos as the locus for Revelation and the Eastern identification of this island with the Fourth Gospel (see Appendix 5).Footnote 36 Western tradition governs the first two readings in which John is exiled to Patmos, where he writes the Apocalypse (Lectio 1), and is subsequently summoned back to Ephesus (Lectio 2). The remaining seven readings return to the Acts by Prochorus to dwell on John's Gospel preaching during his exile. Skipping over John's many miracles on Patmos, the readings focus instead on the reaction of the Patmian Christians to the news of John's impending return to Ephesus. The Patmian Christians beg John to teach them in writing about the signs he had seen in the presence of Christ (Lectio 3). After sending the people home, John leads Prochorus to a deserted mountain (Lectio 4). There they pray and fast for three days before John sends Prochorus back to the city to fetch ink and papyrus. As John is about to narrate his Gospel, the mountain quakes with thunder and lightning and Prochorus falls to the ground, as if dead (Lectio 5). John revives him, and after asking him to sit on his right side, John proclaims ‘In the beginning was the Word’ and dictates the rest of his Gospel to his seated scribe (Lectio 6). The Evangelist then assembles all the Patmians and commands Prochorus to read the Gospel aloud (Lectio 7). John instructs the islanders to make copies of the Gospel for all the churches but to send the original papyrus to Ephesus (Lectio 8), to which John and Prochorus depart (Lectio 9).

Yet John's evangelical ministry on Patmos does not completely overshadow his prophetic status. In his reception of the Gospel by divine revelation, John engages in prophet-like behaviour, through parallels to Moses and Mount Sinai, where the ‘prophet of prophets’ received the Ten Commandments.Footnote 37 This Old Testament parallel is especially evident in the references to the mountain shaking with thunder and lightning on the third day, evoking Exodus 19:16–18: ‘And now the third day was come, and the morning appeared, and behold: thunders began to be heard and lightning to flash and a very thick cloud to cover the mount.’ The effect of this comparison is to portray John as a new Moses, the Patmians as the Israelites, and the Fourth Gospel as equivalent to the Ten Commandments, thus enhancing John's authority.Footnote 38

The conflation of Eastern and Western hagiographic traditions on the feast of John's Return is especially prominent in the second nocturn (see Table 1), the unique moment at which the ‘s-Hertogenbosch rite departs from its own custom of assigning responsories proper to John to draw instead from the Common of Evangelists. The fourth, fifth and sixth responsories quote successively from the first chapter of Ezekiel (1:4–8, 10–11) to depict the prophet's vision of the tetramorph – four identical beings, each with four faces. Ezekiel's prophecy was widely recognised as the inspiration for John's vision of the Four Living Creatures surrounding the heavenly throne in Revelation (4:6–9),Footnote 39 depicted in the Benedictus antiphon of Lauds and the Magnificat antiphon of Second Vespers. In the second nocturn of Matins, the alternating readings and responsories create the following scenario: as John fasts for three days at the deserted mountain, he looks and sees the tetramorph; the mountain quakes from thunder and lightning, Prochorus falls to the ground, and John sees each creature's four faces and four wings; having revived Prochorus and saying, ‘In the beginning was the Word’, John sees the face of a man, that of a lion, bull calf and eagle. This animal imagery common to the prophecies of Ezekiel and John, however, was widely understood to represent the evangelists – the man, Matthew; the lion, Mark; the calf, Luke; and the eagle, John. As evangelists’ symbols, these animals signified more broadly the Gospel itself, and when depicted at the extremities of the Cross, the spread of the Gospel to the four corners of the world.Footnote 40 As heard at Sint-Jan, the Ezekiel-based responsories might thus be understood to mirror the Prochorus-based readings in their underlying synthesis of John's two identities.

Intersecting voices of the visionary preacher and prophet in the versified responsories of Matins

When we consider these Prochorus-based readings in their liturgical – and specifically musical – context, we recognise how the ‘s-Hertogenbosch clergy sought not only to embellish the Western account of John's exile with vivid detail but also to celebrate the intersection of John's evangelical and prophetic attributes. This goal is especially evident in the responsories of the third nocturn that are proper to each feast. As shown in Table 2, the four extant melodies exhibit traits of the ‘later’ style prevalent in chant from the twelfth century onward, demonstrated by the following tendencies: avoidance of standard melodic formulas in the respond and avoidance of ‘classical’ tones in the verse; melodic emphasis on the final, upper fifth, and/or upper octave at the beginning and end of polysyllabic words (called word valency); melodic emphasis on the upper octave at the beginning of phrases (an example of octave valency); use of scalar passages greater than a perfect fourth; and preference for virtuosic melismas.Footnote 41 Rather than borrow from Prochorus, the rhyming texts consisting primarily of eight- and seven-syllable lines with paroxytonic or proparoxytonic accentuation (specified in Table 2) meditate on John's visionary experience as the basis for both preaching and prophecy. Although the visionary link between the Fourth Gospel and the Apocalypse was by no means unique to the church of Sint-Jan, textual and musical subtleties highlighted in the following analysis demonstrate the extent to which the resulting synthesis of John's preaching and prophetic activities at once elaborates on and departs from standard liturgical and hagiographic narratives.

Table 2. Versified Matins responsories for the feasts of the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium and Reversio Ioannis ab exilio

Key: R = respond; V = verse; 8V = octave valency; WV = word valency (F = final; L4 = lower fourth; U5 = upper fifth; U8 = upper octave)

aE = Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium

bR = Reversio Ioannis ab exilio

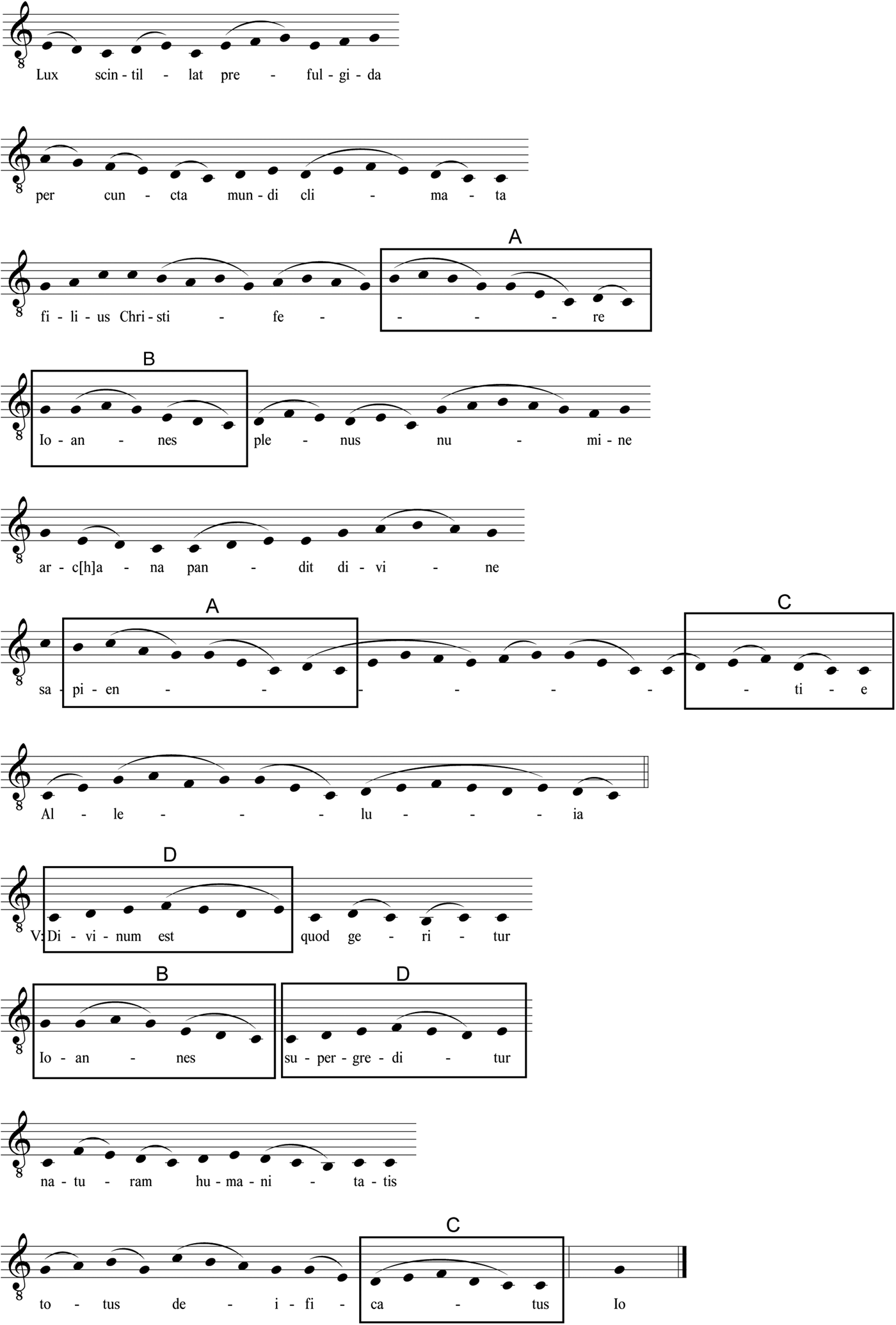

The three proper responsories concluding the Office of Matins on the feast of John's Exile, heard in conjunction with the tale of John's ministry to the Ephesians during his journey to Patmos, portray John in an extraordinary light. The seventh responsory, Lux scintillat prefulgida, boldly identifies John as the luminous and divinely infused revelator who surpasses all of humankind, having himself been deified:

To justify John's access to the heavenly secrets that he reveals, a privilege that is emphasised by its formal position in the repeated phrase (repetendum) at the end of the verse, the third line of the respond alludes to the belief that John was the literal brother of Christ. This idea developed from interpretations of the biblical scene (John 19:26–7) of Mary and John at the foot of the Cross, where, after Christ had chosen him as his mother's adopted son, John could be imagined to miraculously transform into Mary's real son.Footnote 44 John's special kinship to Christ thus grants him singular access to the divine wisdom that subsequently deifies him – John becomes what he contemplates.Footnote 45

These ideas are interrelated musically (see Example 1). A recurring seven note motive (B) on John's name links the phrase ‘Ioannes plenus numine’ to ‘Ioannes supergreditur’, establishing a melodic connection between John as the recipient of divine power in the respond and John as transcendent and superhuman in the verse. Another seven-note motive (D) connects ‘supergreditur’ to ‘Divinum est’ in the preceding line, an association which may have reinforced the divine source of John's superiority. Even more expressive are the lengthy melismas on christifere in the respond prior to the repetendum, sapientie within the repetendum, and deificatus at the end of the verse – the only instances of word valency emphasising the upper octave on the first syllable and the modal final on the last. Of these three words, sapientie receives the most prolonged treatment with twenty-six notes, the longest melisma in the entire chant. Moreover, the sapientie melisma begins with a nine-note motive (A) sung and heard previously at the conclusion of christifere and subsequently ends with a shorter six-note motive (C) that similarly concludes deificatus. John's three extraordinary attributes thus converge musically through this melisma, an association that is prolonged in an abbreviated form in the ensuing musically related Alleluia.

Example 1. Matins responsory Lux scintillat prefulgida for the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Source: NL-DHk 68 A 1, fols. 142v–143r.

The divine source of John's vision receives further elaboration in the eighth responsory, Quid putas seraphin, the melody of which has not survived. The text summons listeners to imagine John's cosmological journey, asking what the highest of the angelic orders, the seraphim, thought as John surpassed them:

Having ascended above the angelic choir,Footnote 47 John receives his vision of the Gospel – evident here through the equation of ‘the Word’ with ‘the Son’ – and subsequently makes it known to the world.

Abstract representations of John's superior visionary experience in Lux scintillat prefulgida, identifying John as a divinely infused revelator, and Quid putas seraphin, depicting his cosmological journey above the highest of the angelic orders, become concretely connected to John's exile on Patmos in the ninth responsory, Ioannes horrido. This chant may initially seem to articulate the standard Western association of Patmos with John's authorship of Revelation and Ephesus with his preaching of the Gospel:

The opening lines portray John as the solitary exile who subsequently experiences his prophetic vision ‘when he was in spirit on the day of the Lord’, paraphrasing Revelation 1:10: ‘I was in spirit on the Lord's day.’Footnote 49 Yet instead of depicting John in the act of writing his vision, as he was commanded to do in the following verse ‘“What thou seest write in a book”’ (Rev. 1:11), the responsory text focuses instead on its vocal source, using the term colloquio, from colloquium – meaning talk, conversation, discussion – to reference the great voice that spoke with him (Rev. 1:10, 12).

The vocal source of John's prophecy is underscored musically by a lengthy sixteen-note melisma on the word colloquio (see Example 2). That this melisma is further embellished with a musically related untexted vocalise (neuma or jubilus), following the Alleluia, identifies the sound of this prophetic voice as angelic – in keeping with the widespread association of wordless melody with angelic simulation.Footnote 50 In the liturgical context of John's Exile, the neumatised conclusion of Iohannes horrido could have been heard at least two ways: as a musical echo of John's ascent through the angelic choir in the previous responsory emphasising John's vision and preaching of the Gospel;Footnote 51 and as the sound of the heavenly voice, perhaps also those of the angels, who participate in his apocalyptic prophecy.Footnote 52 This extraordinary untexted music thus underscores the sublimity of John's two visions.

Example 2. Matins responsory Ioannes horrido for the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Source: NL-DHk 68 A 1, fol. 143r.

These three responsories sung at the conclusion of Matins on the feast of John's Exile share not only a focus on John's privileged status as a visionary, but also more specifically a visionary whose insights did not remain hidden or exclusive but were divulged – as indicated by the verbs pando (to open, disclose, reveal) in Lux scintillat, declaro (to declare, make known, show) in Quid putas, and revelo (to unveil, open, reveal) with ‘vision and dialogue’ in Ioannes horrido.Footnote 53 Alongside joint emphasis on the visual, the vocal dimension becomes increasingly prominent in Quid putas with the question of what the seraphim ‘were saying while they were seeing John’ and especially the elaborate vocalisation in Ioannes horrido. Although, as previously noted, there is no direct correlation between the responsories and the readings, it is nonetheless interesting to note that these three chants are interspersed with the last three Prochorus-based readings focusing on John's evangelizing activities in which his speech is heard most notably in the excerpts read in the third nocturn. Indeed it is John's vocal appeal to Christ that saves the drowning soldier, frees John from captivity and ultimately moves the Patmians to Christian praise. In the juxtaposition of these two narratives, alternating between John's preaching, blessing and possible conversion of the Patmians in the readings and his transcendence and revelatory speech in the responsories, the sound of the Evangelist's two voices – evangelical and prophetic – would have become increasingly vivid and interconnected.

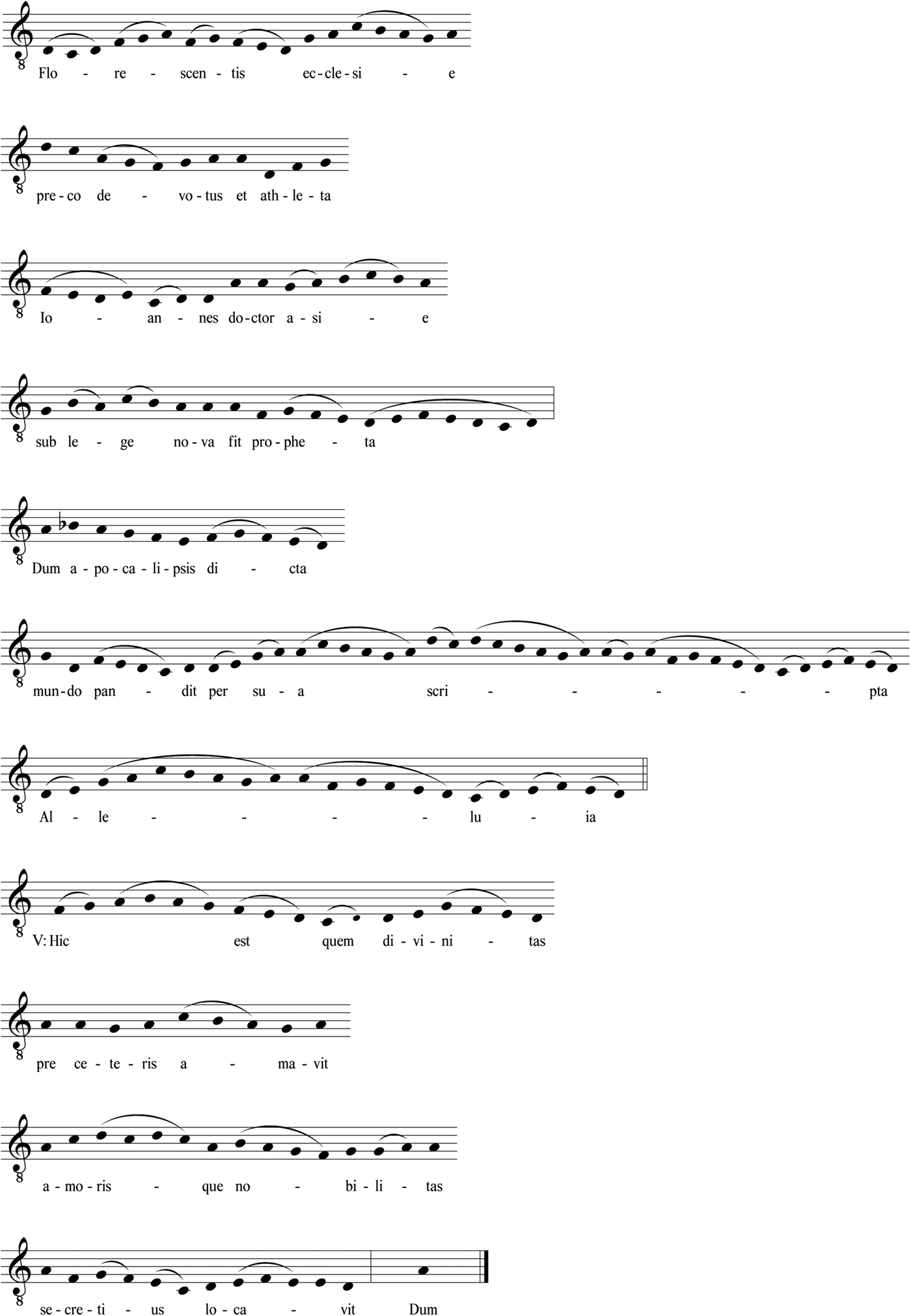

Similar interplay between John's preaching and prophetic activities, as well as his speech and writing, occurs in the three concluding Matins responsories proper to the feast of John's Return. The seventh responsory Florescentis ecclesie identifies John explicitly as both ‘apostle of Asia’ and a ‘prophet under the New Law’ (i.e., the Law of the Gospel):

In performance, John's status as prophet and author of the Apocalypse would have attracted extra attention with the longest melismas falling on the words propheta (eleven notes) and especially scripta (twenty-two notes) further highlighted by word valency emphasising the upper octave on the first syllable and the modal final on the last (see Example 3). That these writings were specific to Revelation would have been reinforced by the syllabic declamation of apocalipsis – an idea reiterated in the repetendum at the end of the verse. Compared to the aforementioned responsory Ioannes horrido for John's Exile, Florescentis ecclesie features the more traditional Western emphasis on the written form of John's prophecy.

Example 3. Matins responsory Florescentis ecclesie for the Reversio Ioannis ab exilio in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Source: NL-DHk 68 A 1, fol. 90r.

The epithet ‘prophet under the New Law’ draws an implicit connection between John, here identified as the prophet of the New Testament, and Moses, the prophet and law giver of the Old Testament. The stone tablets ‘written on both sides’ (in Exodus 32:15) containing the Law of the Old Covenant received by Moses on Mount Sinai might be compared to the sealed book ‘written within and without’ in John's apocalyptic vision (Revelation 5:1).Footnote 55 Moreover, the exhortation by Moses not to add to or take away from God's commandments (in Deuteronomy 4:2) is echoed in John's concluding warning of the dangers that will befall those who ‘add to’ or ‘take away from the words of the book of this prophecy’ (Revelation 22:18–19).Footnote 56 More explicit, widely circulating comparisons between Moses as law giver and John as the preacher of the New Law and recipient of God's grace were inspired by the prologue to the Fourth Gospel, ‘For the law was given to Moses; grace and truth came by Jesus Christ’ (John 1:17). Peter Damian, for example, claimed, ‘If indeed the former [Moses] came forth [as] the minister of the law, the latter [John] came forth [as] the preacher of grace.’Footnote 57 As portrayed in the responsory, John's activities as a herald-like preacher and scribe-like prophet stem from his special status, specified in the verse, as the beloved disciple privy to divine secrets – the perceived source for John's Gospel and apocalyptic visions.

At Matins, Florescentis ecclesie naming the Apocalypse would have been heard between the seventh reading, in which Prochorus reads John's Gospel aloud to the Patmians, and the eighth, in which John instructs the islanders to make their own copy before sending the original papyrus to Ephesus. This reading was answered by the responsory O Ioannes frater altissimi, the melody of which has not survived, comparing John to the ‘river of paradise’, an attribute commonly associated with the spread of the Gospel:Footnote 58

The overflowing river symbolising the widespread dissemination of John's Gospel – among both the Patmians and Ephesians as understood from the accompanying readings – is framed by the vocal form of John's intercessory powers, whose prayers yield access to divine utterances. After hearing of John's return to Ephesus in the ninth reading, the Office of Matins concludes with the responsory Ecce volat aquila, of which only the incipit and verse melodies have survived, quoting from the well-known sequence Verbum dei – sung at Sint-Jan on the feast of St John at the Latin Gate (6 May)Footnote 60 – to portray John as the eagle who surpasses other visionaries and prophets:

This ninth responsory is similar to the seventh, Florescentis ecclesie, in its dual allusions to John as a prophet and a preacher. Yet the reference to John's eloquence and especially the quotation of John's Gospel speech in the verse focuses on the vocal medium for John's preaching, thereby counterbalancing the previous emphasis on the written form of John's prophecy.

That the Office of Matins concludes on these two feasts by designating John so explicitly as both a preacher and a prophet is noteworthy. The standard Western corpus of chants proper to John favour John's status as an apostle, evangelist and virgin over that of prophet.Footnote 62 Although John does appear in this role elsewhere in the ‘s-Hertogenbosch liturgy, his prophetic attribute is always listed among others.Footnote 63 Moreover, the most musically prominent references to John's authorship of the Apocalypse coupled with his evangelical ministry in the responsories Iohannes horrido (on John's Exile) and Florescentis ecclesie (on John's Return) would have each been heard additionally at First or Second Vespers (see Table 1). Textual and musical depictions of John the visionary preacher of the Gospel and visionary prophet of the Apocalypse thus intersected repeatedly to heighten their synthesis.

Conclusion: hagiographic intersections in the office liturgy

We can now add to the artistic and polyphonic innovations of late medieval ‘s-Hertogenbosch the liturgical expansion of the cult of the titular patron of Sint-Jan in which Eastern and Western hagiographic traditions could co-exist. The reconstructed Offices of John's Exile and Return exemplify the subtleties of the saint's ongoing veneration, specifically the desire to embellish and understand previously overlooked episodes of the saint's life and the means by which this ambitious undertaking might be accomplished. These accretions to the Sint-Jan rite reveal how secular clerics fostered the office liturgy as a medium to reflect on the divinely inspired authorship of the Fourth Gospel and Revelation. Looking further afield, this article exposes the extent to which the structure of the office liturgy, alternating between readings and chants that did not necessarily draw from the same source or tell the same story, was conducive to the conflation and synthesis of different hagiographical narratives. The resulting interpretative challenge prompted singers and listeners alike to ponder mysteries of the faith and their potentially intersecting meanings.

Appendix 1: Principal choirbooks preserving office chants sung at Sint-Jan in ‘s-Hertogenbosch

-

NL-SHsta Archief Sint-Jan tot 1629, Inv. 216-1: office and Mass intonation book for the cantor, probably copied for the chapter of Sint-Jan by the brothers of the Gregoriushuis in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, c.1500; parchment, 1 + 139 + 1 folios plus a few interpolated inserts, 370 x 260 mm; Hufnagelschrift.

-

NL-SHbhic Toegangsnummer 1232, Inv. 149: office and Mass choirbook for the Confraternity of Our Lady at Sint-Jan, late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century; parchment, 129 folios, 300 x 215 mm; square notation.

-

NL-SHbhic Toegangsnummer 1232, Inv. 152 (Codex Smijers): choirbook with plainchant and polyphony for the Confraternity of Our Lady at Sint-Jan, copied by the brothers of the Gregoriushuis in ‘s-Hertogenbosch c.1529; parchment, 1 + 14 + CXX folios, 500 x 365 mm; square notation.

-

NL-SHbhic Toegangsnummer 1232, Inv. 159: office and Mass intonation book for the precentors of the Confraternity of Our Lady at Sint-Jan, prepared in 1560 by Philippus de Spina; parchment, 56 folios, 279 x 190 mm; square notation.

-

NL-SHbhic Toegangsnummer 1232, Inv. 162: office choirbook with the liturgy for the dead, for the Confraternity of Our Lady at Sint-Jan, copied by the brothers of the Gregoriushuis in ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the sixteenth century; parchment, 1 + 166 + 1 folios, 390 x 270 mm; square notation.

-

NL-DHk 68 A 1: Antiphoner for the Gregoriushuis in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, c.1520; parchment, 1 + 163 + 1 folios, 480 x 345 mm; square notation.

-

NL-Au I A 23: Antiphoner for the Gregoriushuis in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, dated 1554; paper and parchment, 3 + 224 folios, 425 x 282 mm; Hufnagelschrift.

Appendix 2: Extant sources preserving the liturgy of the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium and Reversio Ioannis ab exilio observed at Sint-Jan in ‘s-Hertogenbosch

-

F-Pn RES B-7881: Festorum compositorum Ecclesie collegiate sancti Ioannis Apostoli & Euangeliste in Buscoducis (title for the pars Hyemalis) and Festa composita siue peculiaria ecclesie collegiate sancti Ioannis apostoli & euangeliste in Buscoducis (title for de festis occurentibus tempore estiuali), printed by Michael Hillenius, Antwerp, c.1525; in octavo, 36 folios (unnumbered). This is the only surviving copy, as documented in Renaissance Liturgical Imprints: A Census (RELICS). This imprint gives only the texts of those items that are proper to the ‘s-Hertogenbosch rite. The Office of St John's Exile includes complete texts for the responsory and Magnificat antiphon plus rubrics for the remainder of First Vespers; complete texts for the nine readings and last two responsories of Matins, plus rubrics for the antiphons and first seven responsories; rubrics for Lauds; and the complete text of the Magnificat antiphon plus rubrics for the remainder of Second Vespers. The Office of St John's Return includes complete texts and rubrics for First Vespers; complete texts for the nine readings and last six responsories of Matins, plus rubrics for the antiphons and first three responsories; complete texts for the hymn and Benedictus antiphon plus rubrics for the remainder of Lauds; and complete texts for the Magnificat antiphon and collect plus rubrics for the remainder of Second Vespers. No musical notation.

-

NL-SHsta Archief Sint-Jan tot 1629, Inv. 216-1: the Office of St John's Exile (fol. 77r) includes only incipit and complete verses for the responsories of First and Second Vespers and an incipit for the Second Vespers Magnificat antiphon. The Office of St John's Return (fol. 85v) includes incipit and complete verses for the responsories of First and Second Vespers, incipits for the First and Second Vespers Magnificat antiphons, and an incipit for the Lauds Benedictus antiphon.

-

NL-DHk 68 A 1: Vespers chants only for the Office of St John's Exile (1V-R, 2V-R and 2V-Am, fols. 142v–143v) and Return (1V-R and 1V-Am, fol. 90r–v). Melodies match the incipits given in NL-SHsta 216-1.

-

NL-Au I A 23: Vespers chants only for the office of St John's Exile (1V-R, 1V-Am, 2V-R, and 2V-Am, fols. 194v–196r) and Return (1V-R and 1V-Am, fols. 111v–112r). Melodies match the incipits given in NL-SHsta 216-1.

Appendix 3: Manuscript copies of the Acts of John by Prochorus documented in Western Europe (cited by Kempf, ‘From East to West,’ 71–2 fn. 10)

-

Extant

-

F-Pn lat. 5357 (13th cent.) for the Benedictine Abbey of St Arnulf, Metz; includes the Messine Gesta Episcoporum and legends of St Patiens of Metz

-

B-Bbsb 14 (13th cent.) for the Premonstratensians of Tongerloo; includes fragments of three legendaries (collections of saints’ lives)

-

B-Br 9871-9874 (13th cent.) provenance/destination is unknown; includes two sermons on St John the Evangelist by Peter Damian

-

CZ-Pu XII.D.13 (14th–15th cent.) provenance/destination is unknown; compendium of varied Latin texts including a life of St Martial

-

B-Lu 115 (1448) for the Croisiers (Crossed Friars) of Liège; includes writings by St Augustine and lives of St Anthony Abbot and St Jerome

-

F-Pm 4318 (15th cent.) for the Carthusians of Hérinnes, near Lille; includes writings by Thomas à Kempis, Pope Gregory I, rules for Carthusians, and two sermons on St John the Evangelist by Peter Damian

-

D-KNa 86 (15th cent.) copied by the Kreutzbrüdern (Crossed Friars) of Cologne; includes legends of St Patiens of Metz

-

Lost

-

Codex ‘Embricensis’ (15th cent.) acquired by Theodor Zahn (19th cent.); includes legends of St Patiens of Metz

Appendix 4: Matins readings for the Missio sancti Ioannis in exilium in F-Pn RES B-7881

Lectio I

Domicianus cesar magnus imperator principibus et civitatibus Ephesiorum maleficos iniquos et impios viros Ioannem sanctum et Prochorum quos pro benignitate nostra multum iam tempus sustinuimus peccantes quotidie in beatissimos deos precipimus in exilium mitti in Pathmos insulam. Primum quidem quia divino cultui deorum iniuriantur. Secundo autem quia legem despiciunt et regem non honorant.

Lectio secunda

Preceptum autem istud pervenit ad Ephesum civitatem. Mox igitur qui missi fuerant a rege tenuerunt nos et posuerunt beatum Ioannem magistrum meum in vinculis et strinxerunt eum fortiter et sine misericordia. Erant autem qui nos ceperant viri procuratores quinquaginta adiutores quoque decem et milites quadraginta cum suis ministris omnes numero centum.

Lectio iii

Postquam autem beatus Ioannes apostolis et evangelista Christi apprehensus est apprehenderunt et me non tantum ligaverunt; sed multis verberibus me et illum affecerunt et verba dura et aspera dixerunt et postmodum usque ad navem ducti summus.

Lectio iiii

Cum autem introducti fuissemus in navim iusserunt nos milites et ministri sedere in medio navis dederuntque nobis pro victu nostro sex uncias panis et unum urceum aque et modicum aceti. Beatus vero Ioannes accipiebat duas uncias panis et octavam partem de aqua; cetera relinquebat mihi.

Lectio v

Tertia autem hora diei sederunt ad prandium abundantes cibariis et potibus. Postquam autem manducaverunt ceperunt ludere et magnis vocibus canere. Hoc igitur facientes et magno gaudio in ipsa navi tripudiantes occurrens unus quidam ex eis miles iuvenis ad proram navis subito ruit in mare. Erat autem pater eius in navi; et factus est planctus magnus super eum et luctus omnibus. Et infelix pater eius voluit se submergere et seipsum in mare precipitare; sed comites non permiserunt.

Lectio vi

Decem autem procuratores et quidam alii cum eis convenerunt ubi erat beatus Ioannes alligatus dicentes ei: Ecce omnes flemus propter malum quod accidit nobis; et quoniam tu sine fletu et dolore existis; Ioannes beatissimus dixit eis: Quid enim vultus ut faciam vobis; Dicunt ei: Si potes adiuvare adiuva nos. Respondit beatus Ioannes: Tot dii vestri non possunt vos adiuvare et assistere vestro militi et sine impedimento illum custodire.

Lectio vii

Transacta autem hora diei sequentis tertia dum esset perditus in mari predictus adolescens; beatus Ioannes tristis et dolens pro eo flexus dolore et planctu omnium qui aderant ait mihi: Surge fili Prochore porrige mihi manum tuam (Erat vero multo ferri pondere aggravatus). Mox autem erectus dedi ei manum meam perrexitque in emenentiorem locum et sustinens vincula sua manibus flevit amare et dixit: Hec dicit filius Dei qui supra dorsum tuum ambulavit pro cuius nomine hec vincula porto ut servus eius redde nobis iuvenem quem absorbuisti vivum et sanum.

Lectio viii

Et in hoc verbo apostoli exaltatus est fluctus maris et elevatus ab imo usque ad summum et eiecit iuvenem qui in mare ceciderat vivum et sanum ad pedes apostoli. Hec videntes cuncti ceciderunt in facies suas coram Ioanne et adoraverunt eum dicentes: Cum eo qui suscitatus fuerat. Vere deus tuus ipse est deus celi et terre et creator omnium creaturarum. Tunc accesserunt omnes et deposuerunt vincula que erant super beatissimum apostolum et fuimus in fiducia magna cum eis. Accesserunt ergo ad apostolum dei dicentes: Domine ecce universa coram te sunt vade liber in pace quo vis nos autem navigabimus in regiones nostras.

Lectio ix

Ait illis magister meus Ioannes: Implete ministerium vestrum secundum preceptum regis et reponite nos in loco a rege constituto et tunc revertamini cum pace in habitacula vestra. Et levantes de loco qui vocatur Lison devenimus in insulam Pathmos et intravimus in civitatem que vocatur Flora. Tradideruntque nos milites secundum precemptum regis his qui recipere nos debebant. Fuerunt autem nobiscum decem diebus et benedictione accepta letantes universi navigando cum pace reversi sunt unusquisque ad propria.

Appendix 5: Matins readings for the Reversio Ioannis ab exilio in F-Pn RES B-7881

Lectio I

Factum est autem dum sanctus Ioannes expulsus esset in exilium a Domiciano imperatore impiissimo in quo exilio apocalypsim scripsit manu propria sicut dominus ei revelavit omnes Asiani episcopi omnisque populis Ephesiorum doluerunt. Domicianus vero cum se Deum ac dominum appellari iussisset et plurimos senatorum in exilium misisset: tandem oppressus aulicorum conspiratione simul et uxoris a senatu damnatus in palacio interfectus est eodem anno quo sanctum Ioannem exilio relegavit Deo curam agente de apostolo suo.

Lectio ii

Hoc quoque diffinitum est tam a senatu quam a Nerva Domiciani successore ut omnes quos in exilium damnaverat revocarentur et facultates suas recuperarent. Venerunt ergo episcopi Asiani et presbiteri et multitudo populi ad insulam Pathmos ut ducerent sanctum Ioannem cum honore in Ephesum.

Lectio iii

Dominoque nostro Iesu Christo gratiam largiente apostolo suo Ioanni per predicationem eiusfere omnes inhabitantes Pathmos insulam crediderent in Christum. Qui audientes quod Ioannes rediret in Ephesum doluerunt valde et congregati ceciderunt omnes provoluti in terram ante pedes apostoli cum lachrymis rogantes et dicentes: Magister bone cur nos derelinquis desolatos teneros scientia imbecilles fide; Verumtamen si disponis redire in Ephesum trade nobis in scriptura signa que vidisti apud filium Dei.

Lectio iiii

Tunc beatus Ioannes misertus est ipsorum propter lachrymas quas fuderant coram ipso et propter supplicationes plurimorum episcoporum dixit ad eos: Filioli mei recedatis et eat unusquisque in domum suam et oretis pro me ad Dominum ut impleris dignetur desyderium vestrum. Et abierunt unusquisque in domum suam. Ioannes vero beatissimus duxit me Prochorum ad quemdam locum desertum ubi fuit mons in quo fuimus tribus diebus.

Lectio v

Mansit quoque ieiunus in oratione beatus Ioannes his tribus diebus. Tertio autem die vocavit me dicens: Fili Prochore vade in civitatem et accipe atramentum et chartas et affer michi huc. Quo facto statim fulgura et tonitrua magna oriuntur ita quod totus mons commoveretur. Et statim cecidi in faciem meam super terram timore nimio perterritus et fui ibi longa mora quasi mortuus.

Lectio vi

Tunc beatus Ioannes propriis manibus suis relevavit me et dixit mihi: Sede a dextris meis. Et aperuit os suum et stetit erectus sursum oculis intendens in celum et dixit hoc evangelium: In principio erat verbum. Et prosecutus est cetera verba evangelii stando. Et ego sedendo scribebam fecimus autem ibi moram duobus diebus et sex horis ipse dicens et ego scribens.

Lectio 7

Cum vero scripsissem evangelium sanctum precepit beatus Ioannes convenire omnes fratres in ecclesia Dei. Et congregati sunt universi; continuo beatus Ioannes dixit mihi: Surge Prochore et lege evangelium sanctum in auribus fratrem nostrorum. Legi cunctis audientibus et letati sunt nimis audito evangelio glorificantes Deum et laudantes magnalia Dei.

Lectio viii

Dixit beatus Ioannes ad universos fratres: Accipite hoc evangelium sanctum et rescribite illud ac reponite in ecclesiis vestris. Illud autem quod scriptum est in chartis debemus ferre in Ephesiorum civitatem. Et cum hoc dixisset petiit licentiam ab ipsis dicens: Filii charissimi Dominus noster Ihesus Christus magister et dilectus meus quo me misit in istam insulam ille mihi in revelatione apparuit et iussit redire in Ephesum ad visitandos fratres qui illic sunt. Vos autem commendo in manibus Domini nostri Iesu Christi qui vos conservet hic et in eternum et benedictione facta recessit ab eis.

Lectio ix

Continuo vero relictis fratribus pervenimus ad littus maris et invenimus navem transeuntem in Asiam: ascendimus in eam et per decem dies navigantes pervenimus in Ephesiorum civitatem.