- EMA

-

ecological momentary assessment

Prevention of childhood obesity is a global priority( 1 ). Given the scale of this problem worldwide, population-level approaches are needed that recognise the importance of access to and availability of healthy foods outside the home. Simply put, the choices people make in relation to food are, to a large extent, dictated by the choices they have. While individual characteristics, such as taste preference, and innate appetite and satiety responses, are clearly important, other factors that are external to the individual, such as food cost and availability, are increasingly being recognised as important determinants of dietary intake( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 , Reference Cohen and Babey 3 ). External food environments, in restaurants, supermarkets, schools or recreation and sports settings, are typically characterised by energy dense, nutrient-poor food items that do not reflect the nutritional guidelines for health. Despite an explosion of research in this area over recent years, our understanding of how to characterise these external food environments remains limited( Reference Kirk, Penney and McHugh 4 ). Improving the validity and application of food environment measures is therefore critical to understanding the causes and consequences of obesity and other chronic diseases( Reference Lytle 5 ), but we are still in the early stages of accurately measuring and evaluating such environments. Progress has been hampered by limitations in the quality of existing measurement tools, the convergence of professionals from disparate fields who employ different tools and technologies (e.g. urban planners, geographers, economists and nutritionists), and the inadequacy of present study designs to disentangle the various components of the environment, which are typically highly complex, contextual and dynamic( Reference Lytle 5 ). With this in mind, it is important to be able to evaluate the nature and suitability of the various methodologies used, and to fully understand the characteristics of what it is we intend to measure. As we move towards implementation and evaluation of population-level interventions aimed at reducing diet-related disease, it is helpful for nutrition professionals to become familiar with the evidence base and their role in contributing to its future development. The purpose of the present paper is to provide an overview of the current status of food environment research, particularly as it relates to childhood obesity prevention. Challenges in the measurement of food environments in childhood settings are described, and opportunities to improve measurement are presented. The paper concludes with examples of population-based interventions that seek to modify the food environment in communities, schools and recreation and sports settings.

Defining the food environment

Research on the environmental determinants of overweight and obesity have increased exponentially since the late 1990s when the term ‘obesogenic environment’ was first coined to describe ‘the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities or conditions of life have on promoting obesity in individuals or populations’( Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 6 ). Defining the obesogenic environment in its entirety is a complex endeavour as the factors that influence individual weight status through its behavioural determinants (healthy eating and physical activity) are many and varied, and the role of context has been historically underexplored. What we do know is that the food environment is a nebulous concept, being complex, dynamic and multi-level; often obscuring what actions should be taken, and at what level, to create supportive environments for obesity prevention( Reference Butland, Jebb and Kopelman 7 ).

Although the food environment is challenging to define, it has many dimensions and levels of influence. In this sense, it may best be explored from an ecological perspective. Ecological models are used to describe individual behaviour with respect to multiple spheres of influence, and are therefore of particular importance for childhood obesity and chronic disease prevention( Reference Green, Richard and Potvin 8 , Reference Sallis, Owen, Fisher, Glanz, Rimer and Viswanath 9 ). Ecological models work within the assumption that providing individuals with motivation and skills to change behaviour may not be effective, if environments and policies make it difficult or impossible for individuals to engage in these behaviours( Reference Green, Richard and Potvin 8 ). As such, a supportive food environment would consist of places and policies that make it convenient, attractive and economical for people to make healthier choices.

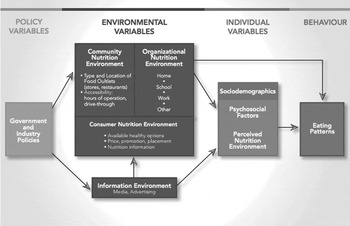

Two key ecological models used to define characteristics of supportive food environments are the model of community nutrition environments( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 ) and an ecological framework proposed by Story et al.( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O'Brien 10 ). The model of community nutrition environments was specifically developed to study nutrition environments outside the home( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 ). According to this model, environmental effects can be moderated or mediated by demographic, psychosocial or perceived environment variables (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Model of community nutrition environments( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 ).

The ecological framework of Story et al. illustrates many complex influences beyond individual-level factors, with particular emphasis on physical environments( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O'Brien 10 ). These are defined as an array of settings where people eat and procure food, including their home, workplace and retail outlets such as grocery stores, corner stores and restaurants; social environments defined as networks and interactions with family, friends, peers and others and influences at the macro level that represent sectors and systems, such as government political structures and policies, and food production and distribution (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. An ecological framework depicting the multiple influences on what people eat( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O'Brien 10 ).

Both frameworks provide useful starting points for summarising research into how food environments influence behaviour. However, although the aforementioned ecological approaches have the potential to improve dietary behaviour and prevent chronic disease, challenges related to measuring the food environment remain, especially regarding individual healthy eating behaviour. For example, in a review that examined environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity behaviours, the authors found a need for research to more clearly define and operationalise environmental influences on health behaviour. With the emerging evidence on the role of the environment there was a particular need to integrate our existing understanding of personal influences on behaviour( Reference Ball, Timperio and Crawford 11 ). With respect to dietary behaviour, another review of associations between environmental factors and energy and fat intake among adults, concluded that no study provided a clear conceptualisation of how environmental factors may influence dietary intakes( Reference Giskes, Kamphuis and van Lenthe 12 ). In the present paper, the authors called for more theoretical development of the relationship between environmental factors and dietary intakes( Reference Giskes, Kamphuis and van Lenthe 12 ). A more recent narrative review of associations between environmental factors and nutrition behaviour found that although the number of studies on potential environmental determinants of food behaviours has increased steeply over the past few decades, there remained a paucity of well-designed studies providing consensus on the environmental determinants of healthful eating behaviours( Reference Brug, Kremers and van Lenthe 13 ). In addition, it has been reported that further work is needed to improve measures of the food environment that incorporate psychosocial variables within all study designs, including self-reported measures( Reference Lytle 5 , Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). The following sections examine approaches and challenges in measuring the food environment in more detail.

Approaches to measuring the food environment

As previously outlined, the food environment consists of a range of potential places where eating behaviour can occur (e.g. home, school and community), and environmental features or elements that provide a cluster of distinctive attributes (e.g. social, physical or political)( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 , Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O'Brien 10 ). Accurate and reliable measures of the food environment within these features and settings are necessary to both understand how environmental factors can influence and/or interact with eating behaviour and to accurately evaluate the effect of any interventions aimed at modifying these relationships( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 ). Such measures normally focus on quantifying or qualifying aspects of the food environment that are thought to influence food intake or behaviours relevant to food intake, such as food preparation practices, eating practices and food-purchasing patterns( Reference Lytle 5 , Reference Brannen, O'Connell and Mooney 15 ). Measures of a particular food environment, e.g. the consumer environment, can be useful to identify important variables that may act as facilitators or barriers for healthy eating and that can be used to characterise other food environments, such as community and organisational environments( Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 ). For example, collecting data on food prices and perceived barriers to healthy eating in the local neighbourhood can inform the design of tools to measure food availability in neighbourhood schools or restaurant cafeterias.

Typically, existing environment measures are divided into two primary types: objective and perceived( Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). The majority of studies investigating the influence of the food environment on healthy eating behaviour use objective measures of the environment including food availability and accessibility. Availability, or the adequacy of the supply of food, is often operationalised as density of food locations (e.g. the number of food locations within a given area). Accessibility refers to the location of the food supply and convenience of travelling to that location, which is commonly operationalised as proximity to identified food outlets( Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 17 ). Studies of food availability and accessibility have employed a variety of measurement tools, but those providing objective measures have increasingly relied on geographical information systems to assess the density and proximity of food locations in a defined area( Reference Bodor, Rose and Farley 18 – Reference Charreire, Casey and Salze 20 ). The use of geographical information systems, a spatial analysis tool, often requires the development of parameters used to define a neighbourhood. Some researchers have based their definition of neighbourhood on census tracts or postal codes, while others have created a predetermined buffer around study participants’ homes or schools( Reference Charreire, Casey and Salze 20 ). New studies are emerging that are moving from the use of these artificial (i.e. administrative) boundaries towards smaller, more meaningful definitions of neighbourhoods, to include community boundaries that are validated by their citizens( Reference Penney, Rainham and Dummer 21 ) or the use of a global positioning system to characterise in a better manner how individuals navigate within or between different environment settings( Reference Hillier 22 ).

It is important to note that although objective measures are useful to describe the food environment, they do not describe all aspects of the environment that may be relevant for understanding dietary behaviour. After all, it does not matter what is objectively within an environment if a person does not perceive it. Perceived measures assess physical (e.g. perceived accessibility, availability and quality) and economic (perceived affordability) influences, predominantly driven by geographic literature, or social support (e.g. from friends and family) from the psychological and social literature( Reference Lytle 5 , Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). Most often, tools for measuring the perceived food environment are restricted to survey questionnaires( Reference Ball, Timperio and Crawford 11 ). In fact, much of the current literature, both perceived and observed, have been considered opportunistic, focusing on measures of facility availability rather than the issues of the social, economic or policy importance( Reference Ball, Timperio and Crawford 11 ). Although the literature has evolved from a focus on availability alone to include issues of affordability, quality and decision support, there still remains a lack of understanding of other dimensions, such as culture, or research that spans several dimensions of the environment simultaneously( Reference Lytle 5 ).

A range of tools is available to measure different aspects of the food environment( Reference Ohri-Vachaspati and Leviton 23 ). Existing tools have been designed and used differently by various groups of health professionals such as researchers, practitioners and community organisations with different priority outcomes( Reference Ohri-Vachaspati and Leviton 23 ). Using the Glanz model( Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens 2 ), Kelly et al. reviewed existing measures of the local food environment according to community (food outlets, restaurants), organisational (worksite, schools and leisure centres), and consumer environments (access and price)( Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 ). They concluded that a considerable range of measures exists, including some validated and reliable instruments. However, validity and reliability were not reported consistently and the quality standards for various tools were not always the same. In the community environment, direct observation methods (e.g. of food outlets) were more robust than indirect methods (e.g. business listings). It was concluded that more work is needed to rigorously evaluate tools and instruments to measure local food environments at the formative stage of instrument development, including reliability and face validity (i.e. the tool should measure all important constructs it is intended to measure)( Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 ). In another review, Ohri-Vaschapati and Levinton( Reference Ohri-Vachaspati and Leviton 23 ) identified at least twelve tools used in school settings, some of which are also appropriate for community settings. Tools identified focused on measuring accessibility and availability of foods, nutrition information, advertising, nutrition quality and types of policies implemented in the school. Some collect data by direct observation (e.g. checklists and inventories)( Reference Hearst, Lytle and Pasch 24 ), whereas others are based on indirect techniques (e.g. school principal surveys and parent questionnaire about child's diet)( Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 25 ). However both aspects, perceived and observed, may need to be measured to capture the whole nature of the environment. Existing components of the food environment have been ‘mapped’ against available tools across both micro- (e.g. schools, home and workplaces) and macro environments (e.g. built and shopping environments), as well as physical, social, economic and political dimensions( Reference Kirk, Penney and McHugh 4 , Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 ).

Challenges with measuring the food environment

The approaches described in the previous section provide a flavour of the variety of ways that food environments have been measured in previous research. The range of approaches in use highlights one of the key challenges within the field of food environment research, which is that there is no consensus, as yet, on how to define a healthy or unhealthy food environment( Reference Osei-Assibey, Dick and Macdiarmid 26 , Reference Miller, Bodor and Rose 27 ). Food environments often comprise a range of different food types in varying proportions making it difficult to dichotomise into healthy or less healthy food environments without an agreed and adequate definition of what we mean by these terms. This also highlights the importance of context, especially socioeconomic and sociocultural context( Reference Chauliac and Hercberg 28 ). A related challenge is that many studies focus on static, bounded definitions of neighbourhood where the food environment is represented by physical distance to food stores within a pre-defined geographic area (e.g. access to neighbourhood grocery stores within a 5 min walk from the home), rather than a dynamic, unbounded definition where the food environment is represented by exposure to a range of food outlets encountered in daily life (e.g. exposure to advertising while driving home from work)( Reference Cummins, Curtis and Diez-Roux 29 ). This is an emerging area of study, where health geographers and epidemiologists are debating the definition of neighbourhood, particularly within different settings( Reference Clapp and Wang 30 ).

Without adequate measures of reliability and face validity, it appears that efforts to modify food environments are moving faster than the theoretical foundation and methodological rigour required to ensure that we can understand and measure such environments accurately which is key to measuring the effect of interventions( Reference Lytle 5 , Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). To illustrate, McKinnon et al. reviewed 137 articles published between 1990 and 2007 and reported that only 13 % of the articles tested for quality of the measurement tools, including inter-rater reliability, test–retest reliability and/or validity( Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). This review and others( Reference Kirk, Penney and McHugh 4 , Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 , Reference Ohri-Vachaspati and Leviton 23 ) conclude that, while a broad range of measurement tools exists to target the food environment, important methodological issues still prevail. Lytle( Reference Lytle 5 ) has grouped these into four categories across all environments: (1) Psychometric standards of existing measuring tools being too low, with little evidence of versatility across populations; (2) Inability of current measures to quantify something as broad as the ‘obesogenic’ environment, leading to production of vast amounts of data and need for data reduction; (3) Inadequacy of present study designs that are either cross-sectional or focused on a single outcome and that cannot tell us about complex and changing environments; (4) Failure to measure the intersection between the individual and other aspects of the environment, such as the social and physical aspects.

Reliability and validity are important to ensure that a tool can be repeatedly used across settings and users, and that it measures what it is intended to measure. It must be predictive of the outcome being assessed. Ideally it should be able to link with a relevant health outcome. However, there are limited examples in the literature where this is the case. School instruments have linked the availability of healthy food with health outcomes such as self-reported BMI for students and student fruit, fat and saturated fat intake( Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ).

Another limitation in the use of existing measures is that, due to the varied nature of the outcomes they intend to assess, these tools can vary enormously in the degree of time commitment, resources and training, data management and processing involved, which affects their applicability and level of measurement error( Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 ). For the same reason, various instruments can measure and produce outcomes of a varied nature which will need to be ‘converted’ to a common score, rank or variable (thus with potential for error and decreased sensitivity) involving reductionistic data techniques that oversimplify the complexity of the environment (e.g. for managing global positioning system data). Instruments for assessing subjective attributes are particularly challenging as they require the user to input their own perceptions, which may not easily be reproduced. For example, with regard to self-reported presence of nutrition information in a school, how is nutrition information defined? When seeking to measure perceived quality of school food, how is food quality defined? More transparency is needed in how subjective attributes are defined, and also how data reduction processes are conducted.

Study designs commonly employed tend to focus on snap-shot observations or comprise interventions that, because of the need to control for confounders, only examine a limited number of outcomes (for examples, see Lytle( Reference Lytle 5 )). Another challenging point is to be able to separate endogenous from context factors, which in many cases are strongly interrelated (e.g. disentangling the characteristics of a neighbourhood from the shopping practices of the residents)( Reference Drewnowski, Aggarwal and Hurvitz 31 ).

Indeed, good measures of the food environment should be able to ‘put the individual back into the equation’( Reference Lytle 5 ), i.e. measure not only the various aspects of the food environment around the individual but also their intersection with individual factors. For this, we need to incorporate measures that collect data on both perceived and objective characteristics of the food environment (such as perceived cost barriers and actual food prices); and assess how the social and physical environment in which people make food-related decisions directly influence their actions( Reference Holsten 32 , Reference Devi, Surender and Rayner 33 ). Individual food-related practices (e.g. shopping and food preparation) may be strongly shaped by external influences such as socioeconomic status, and new approaches such as mapping area distribution of house prices, may help to understand in a better manner the intersection between individuals and environments( Reference Monsivais, Aggarwal and Drewnowski 34 ). Approaches such as this are starting to illustrate that previously underexplored factors (e.g. ability to purchase a house in a certain area (socioeconomic status level), or deeply rooted family routines (e.g. eating at a table) are playing an increasingly important role in shaping food shopping and eating practices in Western societies, and therefore have the potential to influence obesity and related health outcomes( Reference Brannen, O'Connell and Mooney 15 , Reference Drewnowski, Moudon and Jiao 35 ).

There is a need to define in a better manner the types of foods that should be the focus of intervention( Reference Miller, Bodor and Rose 27 ). Various systems to classify healthy and less healthy foods have been used to examine associations between the food environment and food-related behaviours. However, conclusions need to be considered in light of the limitations of each method. For example, Pechey et al.( Reference Pechey, Jebb and Kelly 36 ) have recently used the UK Food Standards Agency nutrient profiling score to investigate the association between purchasing patterns and socioeconomic status in a nationally representative sample of people in the UK. Nutrient profiling scores assign a score to a particular food based on the presence or absence of beneficial/detrimental nutrients such as fibre, protein, fat, sugar, saturated fats and vitamins (for review, see Drewnowski & Fulgoni( Reference Drewnowski and Fulgoni 37 )). This study found that lower socioeconomic status groups (as defined by occupational level) generally purchased a greater proportion of energy from less healthy foods and beverages than those in higher socioeconomic status groups. Computing such scores can be time consuming, and some foods may have inflated scores due to naturally occurring nutrients (e.g. dried fruit and nuts). Therefore input into the design and validation of such measures from a nutrition professional is important. The use of the terms healthy and unhealthy for food items is also problematic. An alternative used by Johnson et al. classified foods as ‘core’ (e.g. cereals, vegetables and dairy) and ‘non-core’ (e.g. fats, crisps and biscuits) to reflect foods that might be considered healthy v. those that are less healthy( Reference Johnson, van Jaarsveld and Wardle 38 ). This study revealed that children's consumption of one group of foods or the other was associated with what parents consumed. Preferences were important for the ‘core’ or healthy food intake only, while availability and television exposure influenced intake of the ‘non-core’ (less healthy) food predominantly, further highlighting that both the individual and family environment need to be targeted to successfully change the balance of core and non-core foods in children's diets.

Promising directions

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) has been used to try to fill in the gap linking the environment with actual individual behaviour. EMA was originally developed in the field of clinical psychology to study behaviour based on the repeated sampling of participants’ current behaviours and experiences in real time, within their natural environments( Reference Shiffman, Stone and Hufford 39 ). One aim of EMA is to overcome common limitations such as recall bias and lack of ecological validity. EMA has recently been applied to nutrition to evaluate actual eating behaviour within a particular food environment. For example, EMA was introduced in national surveys in the UK( Reference Stephen, Mak and Fitt 40 ), the National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme Years 1–3, and the Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children. Both National Diet and Nutrition Survey and Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children food diaries incorporate the following contextual questions: where was the food consumed; with whom; was it consumed at the table; and was the television on or off. Using this methodology, Mak et al.( Reference Mak, Prynne and Cole 41 ) were able to demonstrate that structured settings (school and childcare) facilitated fruit and vegetable consumption in 1–5-year-old children in the UK and that eating at the table and having the television off during family meals was associated with higher fruit and vegetable intake. Very importantly, this study revealed that fruit consumption behaviour in children is different from vegetable consumption and should be targeted separately, perhaps using different measurement tools. EMA is unique in that it relates environmental factors to actual eating behaviour, something that cannot be performed by geographical information systems, eating habits questionnaires, parental surveys and other non-temporalised methods.

The unique challenges in studying children in food environment research

With childhood obesity prevention being a high priority for the policymakers, there are unique developmental considerations involved in modifying food environments for children and adolescents. At early ages, food choice is largely dictated by the family food environment. The family food environment has been conceptualised in terms of food availability within the home( Reference Baranowski, Watson and Missaghian 42 ), parental influences on food-related behaviours (e.g. modelling and nutrition knowledge), and family routines (e.g. television viewing during meals)( Reference Brannen, O'Connell and Mooney 15 , Reference Johnson, van Jaarsveld and Wardle 38 , Reference Campbell, Crawford and Ball 43 ) and linked with a number of dietary outcomes among children( Reference Johnson, van Jaarsveld and Wardle 38 , Reference Campbell, Crawford and Ball 43 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 44 ). Therefore, in trying to understand how modifications to food environments may help in the prevention of childhood obesity, we must also consider food availability within the home, as well as parental influences on food choice. For instance, parental support has been highlighted as important in the implementation of school food policies and interventions that include both an out-of-home environmental and a family component have achieved higher success rates than those that have focused only on an out-of-home environmental change( Reference Baranowski, Mendlein and Resnicow 45 ).

During adolescence, youth tend to gain autonomy from the parents and therefore may be exposed to more varied food environments than the younger children. Outside the home environment, most research on the food environments of younger children has focused on the school setting( Reference Katz 46 ). During adolescence, other settings such as fast-food restaurants, convenience stores and even worksites may become independently accessible to youth( Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French 47 ). Story et al.( Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French 47 ) reported that one-third of all teen eating occasions took place outside the home and nearly half of those also occurred outside of school, suggesting that the broader community food environment may have an important effect on adolescent eating habits. Despite gains in autonomy during this developmental stage, the family's role in helping adolescents to negotiate the food environment should not be underestimated( Reference Brannen, O'Connell and Mooney 15 ). Family research highlights the role of parents in chauffeuring children to and from organised activities and social engagements which may occur outside of walking distance( Reference Schwanen 48 ). Some pilot work using global positioning system suggests that youth travel involves much greater distances than would be assumed using traditional neighbourhood boundary approaches( Reference Wiehe, Hoch and Liu 49 ). Thus, youth exposure to obesogenic food environments is perhaps even more likely than adult exposure to be mischaracterised by traditional neighbourhood-based approaches.

Modifying food environments: some examples from the literature

Although there remain a number of challenges in food environment research, there are also some good examples of interventions that have successfully modified a range of food environments, and there are many more than can be featured in the present paper. In support of a prevention framework at national, regional or local levels, there is mounting scientific evidence to suggest that these broader interventions for the prevention of childhood obesity can be effective( 1 ). A recent Cochrane review highlighted several promising components that appear to be successful, including supportive environments and cultural practices that enable children to eat healthier foods and be active throughout each day, support for teachers and other staff to promote strategies and activities, and parental support and home activities that encourage children to be more active, eat more nutritious food and spend less time in screen-based activities( Reference Waters, de Silva-Sanigorski and Hall 50 ). In particular, approaches to interventions in the area of childhood obesity prevention, including social marketing campaigns with and without a focus on environment and policy changes, have showed promising results. In this section, three settings for initiatives and interventions to measure and modify food environments are discussed: communities, school and leisure settings.

Community-level interventions

There are several examples internationally of community-level interventions that have targeted weight status. One European example is the Fleurbaix-Laventie programme which successfully, over a 13-year period, stemmed the growth in childhood obesity rates in two communities in France, while the obesity rates in neighbouring communities were more than doubled( Reference Romon, Lommez and Tafflet 51 ). Twelve years after its inception, the difference in the prevalence of overweight and obese children between the Fleurbaix-Laventie programme and the control towns was significant (8·8 v. 17·8 %; P<0·0001). However, it took more than 8 years for the decline in prevalence to become apparent, indicating that sufficient time needs to be allowed for the interventions to be successful.

A similar intervention in North America (Shape Up Somerville) employed a community-based participatory research approach to change the local environment to prevent unhealthy behaviours in the early elementary school-aged children( Reference Economos, Hyatt and Goldberg 52 ). This intervention included enhancing the quality and the quantity of healthy foods for students through school food service, in-school and after-school curricula and establishing safe routes to school. The intervention also promoted additional changes within the home and the community to provide reinforcing opportunities and improved access. These intervention components required parent and community outreach (newsletters, attending events and media releases), working with restaurants to enhance food options and training for medical professionals. Additionally, there was a focus on policy change during the intervention, in which various community policies were developed to promote and sustain change. These included a school wellness policy, new policies and union contract negotiations that led to enhancements of the school food service, expanded pedestrian safety and environmental policies, the adoption of a healthy meeting and event policy, and a city employee fitness wellness benefit( Reference Economos, Hyatt and Goldberg 52 ).

Also, in North America, Chang et al. describe a state-wide initiative in Delaware, that used a simple message (‘5-2-1-almost none’) for healthy lifestyle to improve the BMI of children( Reference Chang, Gertel-Rosenberg and Drayton 53 ). This project promoted the message of at least five servings of fruit and vegetables, no more than 2 h of screen time, at least 1 h of physical activity and almost no sugar-sweetened beverages( Reference Chang, Gertel-Rosenberg and Drayton 53 ), and focused on changing children's behaviour by working with various stakeholders in the places where children spend most of their time (e.g. child care, primary care and schools). What is interesting in this example is the ability of the initiative to convey a series of complex behaviours within a relatively simple ‘prescription’. These initiatives demonstrate the promise of utilising different approaches to community-based interventions delivered at multiple levels of influence for the purpose of preventing childhood obesity.

School-based interventions

A population-level intervention in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia provides an example of the effect of food environment modifications in the school setting. Conducted in 2003, the Children's Lifestyle and School-performance Study I demonstrated the poor state of children's nutrition behaviours and that school food environments were contributing to the issue of poor diet quality and unhealthy weights( Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald 54 , Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald 55 ). The study also found that students attending schools that had implemented a comprehensive school health approach (i.e. by improving the school food environment, creating healthy school policies, engaging parents and community members and connecting health with learning) had healthier diets and were less likely to be overweight and obese. These research findings helped to inform school policy action in the province( Reference McIsaac, Sim and Penney 56 ), including the introduction of a comprehensive Food and Nutrition Policy for Nova Scotia Public Schools in 2006, with full implementation expected in all public (state) schools by 2009. The 2011 Children's Lifestyle and School-performance Study II provided an opportunity to learn about how policies aimed at modifying the food environment were implemented and to explore the relative effect of a nutrition policy on children's health behaviours and weight status over time. Emerging findings from this study suggest that although some positive changes (e.g. modest improvements in diet quality, energy intake and healthy beverage consumption were observed) further action is needed to curb the observed increases in the prevalence of childhood obesity( Reference Fung, McIsaac and Kuhle 57 ). Qualitative research conducted within the Children's Lifestyle and School-performance Study II study also provided an important insight on factors facilitating and preventing policy implementation within schools and the importance of establishing a supportive school community culture to create meaningful change in the school food environment( Reference Mcisaac, Read and Veugelers 58 ). Further research will be pinpointing the specific school practices and processes that are most likely to have an effect on children's diet quality and weight status. So far, the published results re-emphasise that collaborative action is needed across levels of the socioecological model to ensure that healthy food is available and accessible to children at all times.

Recreation and sport settings

The success of the school food policies in reducing children's exposure to unhealthy foods has generated interest in using similar strategies in other settings such as recreation and sport settings (e.g. publically funded pools, gymnasiums and arenas). These settings are increasingly recognised as important community resources for health promotion, yet the food environments within them are often neglected in favour of energy-dense fast and processed foods that are quick to prepare, cheap to provide, have a long shelf-life and are profitable( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 59 ). Recent evidence suggests that individuals may see food and fitness as competing priorities and that, faced with time pressures, families prioritise leisure time physical activity over the preparation and consumption of healthy meals( Reference Chircop, Shearer and Pitter 60 ). Recreation and sport settings therefore offer an important opportunity for both physical activity and healthy eating to occur simultaneously, mitigating the challenge of prioritising one over the other( Reference Chircop, Shearer and Pitter 60 ). Research in the Canadian province of Alberta provides an interesting case study in this setting. The Alberta Nutrition Guidelines for Children and Youth (ANGCY) were released in June 2009 to facilitate children's access to healthy food and beverage choices within schools, childcare, and recreation and sports settings in Alberta. The ANGCY guidelines include a food rating system which classifies foods into ‘Choose Most Often’, ‘Choose Sometimes’ and ‘Choose Least Often’ categories based on the amount of fat, protein, fibre, sugars, protein, sodium and selected micronutrients in the product. One year following their release, however, only 14 % of a random sample of Alberta recreation facilities had adopted the guidelines and only 6 % had implemented them, rates of uptake that are much lower than within the school or childcare setting. Three recent papers have explored the reasons for the lack of uptake in the recreation and sports setting and commented on the barriers and the facilitators of adoption and implementation of the ANGCY guidelines, through a survey of a random sample of Alberta recreation facilities( Reference Olstad, Lieffers and Raine 61 ), a single case study of a facility that had adopted and implemented the guidelines( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 62 ) and a multiple case study comparing two adopting facilities (with different levels of adoption) to a non-adopting facility( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 63 ). Recreation facilities that participated in this research developed policies that increased the availability of healthy choices (i.e. options in the ‘Choose Most Often’ category) but continued to allow unhealthy choices to be sold alongside them. According to Olstad et al.( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 59 ), this proved to be the most important barrier to the policy's achievement of meaningful change in facility food environments( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 62 ). Observations of children within the facilities examined revealed that they were also still more likely to make unhealthy choices( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 62 ). Thus, it is clear that the implementation of nutrition guidelines in these settings is complex, that strong government action is required in order for their effect to be gleaned at the population level, and that monitoring and evaluation are essential to support meaningful change in this area( Reference Olstad, Raine and McCargar 59 , Reference Olstad, Lieffers and Raine 61 ). Thus, simply providing access to healthier choices in the presence of unhealthy choices may not be sufficient incentive to change, as has been observed within school settings where foods with poor nutritional value are available alongside healthier options (e.g. Briefel et al.( Reference Briefel, Crepinsek and Cabili 64 ) and Kubik et al.( Reference Kubik, Lytle and Hannan 65 )).

Future research directions

The present paper has provided an overview of the current progress, and the challenges, in the area of food environment research over recent years. This review is not exhaustive but provides several areas for future research to improve how we define, and measure, the food environment in a range of settings. It is clear that the need to act has overtaken our theoretical understanding and evidence base, meaning we are still not in agreement as to what should be measured and why. This is certainly not a surprise given the number of challenges that still exist in the current methodologies to measure the food environment. It is now time to focus on developing better theoretical understandings of how people and environments interact, develop and improve our measures, while being mindful of the need to apply them within complex contexts( Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre 66 ). The literature reviewed in the present paper suggests that more work is needed on the following aspects of food environment research( Reference Kirk, Penney and McHugh 4 , Reference Lytle 5 , Reference McKinnon, Reedy and Morrissette 14 , Reference Kelly, Flood and Yeatman 16 ): (1) Evaluating and contributing to evidence that furthers our understanding of the intersection between individual behaviour and external factors, including measures of both perceptions of the individuals as well as the objective measures from the environment; (2) Emphasising good instrument development, i.e. ensuring tools are tested for psychometric properties such as validity and reliability, and that they link with the observed behaviour we intend to measure; (3) Publishing detailed protocols for instrument use including definitions (objective whenever possible) of the outcome measures, and the protocols for data processing and data reduction; (4) Choosing appropriate study designs with proper consideration of confounding, measurement error, causal inference and cost. Consideration of the natural experiments and other ‘real world’ approaches is warranted but these must be implemented with appropriate methodological approaches.

Given that much of the available research is conducted in the school setting, there is also a need to understand how the policies related to improving the food environment are being implemented and what policy changes are needed to facilitate implementation in schools. We also need to define how the availability and the accessibility of foods are operationalised for children and adolescents, since they may be quite different from adults. These nuances also need to be applied to other settings where food is available and we need to do a better job of understanding the other contextual factors that are working to help or hinder behaviour change. Food outlet owners may compromise profits slightly only if changing the environment is accompanied by consumer demand (therefore offsetting losses in the long-term), and provides a ‘healthy’ company image( Reference Condrasky, Ledikwe and Flood 67 , Reference Waterlander, Steenhuis and de Vet 68 ). The challenges of this type of research are partially due to the complexity of the person–environment interaction under investigation, the current tools and the methods being employed and the multiple disciplines contributing to the evidence base. Despite these challenges, multi-level interventions are underway that show promising results with the potential to be refined and improved to help us to understand and create supportive environments for healthy eating for children and their families.

There is still more to be done in creating social norms that recognise the value of access, availability and affordability of healthier food choices. This is an important challenge for nutrition research in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Sherley Beasley to the literature search used in this work.

Financial support

SFLK and EAR received salary support from MRC Human Nutrition Research to develop some aspects of this review.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authorship

S. F. L. K. presented the paper at the Irish Nutrition Society meeting, June 2013 and conceived the overall direction of the review. All the authors contributed to the development and the critical review of the manuscript.