Food banks (or food pantries in the USA) are established charity organisations across many Western countries, proliferating in the USA and Canada in the 1980s(Reference Tarasuk and Davis1,Reference Poppendieck2) , in some Nordic countries in the early 1990s(Reference Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti3) and in other European nations such as Germany and the Netherlands through the 2000s(Reference Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti3). In the UK, they have only become widespread since 2010(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4–Reference Riches6). They most commonly operate as voluntary projects where people can receive free bags of groceries in the face of insufficient finances for food. They are now established features of informal welfare systems, and funding from food corporations and governments show how normalised they have become(Reference Riches6). Research in Western countries has examined the relationship between food insecurity and food bank use from a population perspective(Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk7–Reference Heflin and Olson10) and considered the nutritional quality of foods food banks offer(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt11,Reference Simmet, Depa and Tinnemann12) , experiences of people using food banks(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt11) and ethics of charities being relied on to support people experiencing food insecurity(Reference Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti3). In the UK, research focused on food insecurity and food bank use was relatively rare before the rapid spread of food banks and growing usage from 2010 but since then, has burgeoned. The present paper reviews this body of evidence, asking, what is known about food insecurity in the UK, and what is the role of food banks among people experiencing food insecurity?

Food insecurity in the UK

Use of food insecurity concept and measurement prior to regular monitoring

Household food insecurity is a widely used concept in high-income countries to describe ‘uncertainty about future food availability and access, insufficiency in the amount and kind of food required for a healthy lifestyle, or the need to use socially unacceptable ways to acquire food’(Reference Anderson13). A number of survey instruments have been developed to measure and monitor household or individual-level experiences of food insecurity in high-income countries(Reference Carrillo-Alvarez, Salinas-Roca and Costa-Tutusaus14), with one of the most commonly used being the United States Department of Agriculture's Household Food Security Survey Measurement Module (HFSSM) or Adult FSSM, which excludes questions referring to children in households. Measurement of food insecurity in large population-based surveys has led to a large body of research on how it associates with non-communicable diseases(Reference Liu and Eicher-Miller15) and measures of mental health(Reference Maynard, Andrade and Packull-McCormick16,Reference Burke, Martini and Çayır17) , among other social and well-being outcomes. Of particular concern to the nutrition and dietetics community is how food insecurity is associated with poor dietary quality and nutrient intakes(Reference Hanson and Connor18).

In the UK, the term household food insecurity had not widely been used among researchers, policymakers or the third sector until recently. In 2003, however, Dowler highlighted how the term ‘food poverty’ was gaining traction in the UK and pointed out that it was conceptually similar to the concept of household food insecurity used in US literature(Reference Dowler19). Dowler defined food poverty as ‘the inability to acquire or consume an adequate quality or quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so’, which is the definition that comes from early qualitative and conceptual research of food insecurity in the USA by Radimer and colleagues (at the time, used to describe ‘hunger’ but referring to food insecurity)(Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell20,Reference Radimer and Radimer21) . Research into food insecurity experiences in the UK was relatively scant at that time and predominantly qualitative(Reference Dowler19,Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti22) , though quantitative studies examining the patterning of diets and nutrition by socio-economic status were common(Reference Smith and Brunner23). Additionally, questions asking about households' abilities to eat certain foods (e.g. fruit and vegetables, meals with a protein source) and participate in social norms around eating (e.g. number of meals a day, ability to have friends over for a meal) were a part of material deprivation measures in the UK and gathered across the European Union(Reference Dowler19). One of the first quantitative pieces of research that used a validated survey instrument to capture food insecurity (the United States Department of Agriculture's HFSSM) was a survey of people using general practitioner practices in London conducted in 2002(Reference Tingay, Tan and Tan24). This study suggested high levels of food insecurity among general practitioner patients, though levels ranged from 3 to 32 % across general practitioner practices. Two place-based surveys targeting mothers of children recruited into birth cohorts also included food insecurity measurement in the 2000s: the Southampton Women's Survey(Reference Pilgrim, Barker and Jackson25) and a sub-study from the Born in Bradford birth cohort study(Reference Power, Uphoff and Stewart-Knox26). In the Southampton women's study, 4⋅6 % of women were classed as moderately or severely food insecure(Reference Pilgrim, Barker and Jackson25). In the sub-sample of women from the Born in Bradford cohort, 14 % of women were moderately or severely food insecure. Of course, given the targeted nature of these studies, it is not possible to generalise these findings to the general population, but they give an idea of the scale of the problem in these samples at that time.

Over 2003–2005, a survey targeting households in the top 15 % of deprivation levels in the UK was commissioned by the Food Standards Agency (referred to as the Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey) and included the United States Department of Agriculture's Adult FSSM(Reference Nelson, Erens and Bates27). Among the adults in this high-risk population, 14 % were classified as moderately or severely food insecure. However, this one-off survey was not repeated, and to our knowledge, no government body commissioned a survey to capture food insecurity in the UK population again until 2016. Of note is that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs was responsible for reporting on food insecurity, but this largely consisted of reporting on the food supply, food prices and household food expenditure, and did not include any data on individual or household measures of insufficient or insecure access to food(28).

Regular monitoring of food insecurity in the UK

Whilst these studies suggested food insecurity was a problem for some groups prior to 2010, it was the rapid rise in numbers using food banks reported in the media from 2012(Reference Wells and Caraher29) and the qualitative research highlighting experiences of food insecurity among food bank users(Reference Perry, Williams and Sefton30) that led to many third-sector organisations and academics calling for the need for measurement of food insecurity in the population to understand its scale and who was most at risk(Reference Taylor and Loopstra31–Reference Lambie-Mumford and Hunger33).

In 2016, the Food Standards Agency included the United States Department of Agriculture's Adult FSSM, with a 12-month recall period, in Wave 4 of their Food and You Survey(Reference Bates, Roberts and Lepps34). Whilst not representing the whole of the UK, as Scotland has its own Food Standards Agency, this was the first attempt by a UK government agency to measure food insecurity in a nationally representative survey. These data were the first to show how widespread the problem of food insecurity was in the general UK population, with 13 % of adults experiencing marginal food insecurity and a further 8 % experiencing moderate or severe levels. From 2016, the Food Standards Agency has continued to include food insecurity in their Food and You Survey(35) and its successor, Food and You 2(36). In addition, from 2019 to 2020, the Department for Work and Pensions is also has included the Adult FSSM in their Family Resources Survey, using a 30-d recall period(37). Based on these data, prior to the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, 8 % of adults were experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity each month, with a further 6 % experiencing marginal levels. In some areas, for example, the North East and North West, levels were much higher with 11 and 10 % of households experiencing moderate or severe levels food insecurity, respectively(37).

In addition to revealing the scale of food insecurity, these data have enabled identification of socio-demographic groups that experience significantly higher levels of food insecurity than their counterparts (e.g. see Table 9.6 available from (37); see also (Reference Armstrong, King and Clifford38). These include adults with disabilities, adults who are unemployed, adults in receipt of Universal Credit, households with children and adults from some Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups. Multivariate analyses of Food and You data from 2016 have shown that unemployment, low incomes and disability are significant predictors of severe levels of food insecurity(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk39).

Food banks in the UK

Growth in number of food banks and distribution of food parcels

Whilst it is clear from the data outlined earlier that insecure and insufficient access to food were experiences among low-income households in the 1990s and 2000s, food banks only became widespread from 2010. Their proliferation is linked to the recession of 2008 and subsequent austerity measures implemented, which reduced spending for local services, reformed the benefit system and reduced funding for financial crisis support in local authorities in England(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Taylor-Robinson5,Reference Lambie-Mumford and Green40–Reference Beck and Gwilym43) . The Trussell Trust is a national network of food banks, which established its first food bank in 2000 and became a social franchise in 2004, allowing community groups, mostly Christian churches at that time, to become members and start their own food banks(Reference Lambie-Mumford44). But it was only after 2010 that the Trussell Trust model spread rapidly across the UK(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45). Outside of the Trussell Trust, independent food banks have also been operating, but a survey of independent food banks operating in 2018–2019 found that in the representative sample of 114 food banks, just under 10 % were distributing food parcels before 2004, and that the majority, 75 % of the sample, started in 2010 or later(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). Today, it is estimated that food banks operate in most local authorities(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45), with about 430 Trussell Trust members distributing food parcels from about 1300 client-facing food bank distribution centres(46), and at least 1170 independent food banks operating outside of the Trussell Trust network, though this does not include schools, hospitals or Salvation Army centres that provide food parcels(47). The latter data were collated by the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN), which was established in spring 2016 to provide mutual support and share resources among food aid providers operating outside of the Trussell Trust, among other aims(Reference Independent Food Aid Network48). About 550 non-Trussell Trust food aid providers, predominantly food banks, are part of IFAN.

Of course, the provision of food in response to concerns about hunger in the UK population was not new(Reference Dowler and Lambie-Mumford42). Other forms of food aid have a long-standing history in this country context, with soup kitchens and later soup runs being among the most visible(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti22). However, the establishment and proliferation of national-scale organisations to facilitate or coordinate food assistance in the form of food banks is new since 2010, systematically supporting a basic provision of food for people to take away, prepare and eat off site, in addition to financial transfers through the social security system, largely in recognition of the inadequacy of the level of financial support and also because of issues with the system or operations of the system which caused benefit payments to be delayed or stopped(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti22). Of note is that initially the Trussell Trust saw themselves as primarily responding to people in financial ‘emergencies’ and a stopgap until financial issues could be solved (i.e. when benefit payments came through, etc.)(Reference Lambie-Mumford44). To some extent, their data reflected these situations, with problems with benefits and benefit delays being among the most frequent reasons for referral to food banks. However, in light of benefit freezes and rising living costs, there has been a steady increase in the number of referrals being attributed to ‘low income’, which suggests that food banks are supporting people with chronically low incomes, rather than providing stopgap support(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45). This shift may reflect that benefit levels have eroded over 2014–2019(Reference Corlett49).

In the absence of monitoring of food insecurity data prior to 2016, quantitative data on food bank usage have been used to describe the scale of hunger. Even with survey data, many local authorities rely on food bank statistics because they are available at the local level(Reference Shaw, Loopstra and Defeyter50). Data on food bank use have primarily come from The Trussell Trust, which requires food banks in its network to keep record of the number of households and the corresponding household members who receive food parcels. Data tracking is facilitated by the use of the Trussell Trust's referral model, where redeemed referral vouchers enable data collection on the number of household members receiving help and reason for referral. The Trussell Trust has been regularly reporting their end-of-year statistics and mid-year statistics since 2011, with trends showing a steady increase in the number of times adults and children have received food parcels(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45,51) . In their most recent report of end of year statistics, people were helped by food parcels 2⋅17 million times over 2021–2022, compared to 1⋅20 million in 2016–2017(51), and fewer than 500 000 in 2012–2013(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45). Data on individuals are not reported, though data on the frequency of use among recipients have been reported to be about 2⋅6 times per year(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45). Thus, these data cannot be interpreted as prevalence of Trussell Trust food bank use, but rather are an indicator of the volume of food bank usage, with both an increase in the number of people receiving food parcels or an increase in the number of times an individual or household receives food parcels increasing the volume of food parcels distributed.

IFAN has periodically collated data on food bank use from their membership, reflecting the volume of food parcel distribution among a subset of independent food banks that are not part of the Trussell Trust network. Their latest data from December 2020, from a sample of IFAN members, suggested food bank food parcel distribution in 2020 was more than double what it was in 2019(52). Based on an almost complete audit of independent food banks operating in Scotland in 2019, IFAN data also showed that independent food banks provided a near equivalent of food parcels as Trussell Trust food banks, though ratios may vary across the country and by how independent food banks operate(53).

Whilst there were debates about whether the rise in food bank use reflected a growing amount of food bank assistance available or a genuine rise in need in the population(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Taylor-Robinson5,Reference Sosenko, Bramley and Bhattacharjee41) , there has been evidence that vulnerability to food insecurity has risen in the UK. An analysis comparing levels in 2004 observed among low-income households from the aforementioned Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey(Reference Nelson, Erens and Bates27) to low-income households from the 2016 Food and You Survey(35) found that when matched on participant characteristics, there was strong evidence of a rise in food insecurity among low-income households, from 28 to 46 %(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk39). Importantly, however, the data from the 2016 survey also allowed the scale of food insecurity in the population to be compared to the volume of food parcel distribution from the Trussell Trust network for the first time. Based on the prevalence of food insecurity among adults, it was estimated that 10⋅2 million adults were experiencing marginal, moderate or severe food insecurity in 2016, with 1⋅3 million experiencing severe food insecurity(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk39). The estimated number of individual adults using Trussell Trust food banks at that time was only 324 000, suggesting fewer than one in four adults with severe experiences of food insecurity were using Trussell Trust food banks(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk39).

Further evidence of a wide discrepancy between the numbers of people experiencing food insecurity in the UK and the numbers using food banks come from the 2021 Food and You 2 Survey, which included a measure of food bank use alongside food insecurity measurement(Reference Armstrong, King and Clifford54). In 2021, 13 % of adults were classified as marginally food insecure in this survey and an additional 15 % were classified as moderately or severely food insecure. In response to a question asking respondents whether they ‘received a free food parcel from a food bank or other emergency provider in past 12 months’, only 4 % of adults reported this(Reference Armstrong, King and Clifford54). These figures highlight that levels of moderate and severe food insecurity are 3⋅75 times higher than food bank use.

These data illustrate that food banks do not appear to reach the majority of households experiencing food insecurity in the population. A discordance between experiences of food insecurity and food bank use has been observed in other data sources as well(Reference MacLeod, Curl and Kearns55,Reference Prayogo, Chater and Chapman56) . This is important for understanding the role of food banks among people experiencing food insecurity in the UK: any role is limited to those they reach. However, even when food banks serve people experiencing food insecurity, the impact they have may be limited.

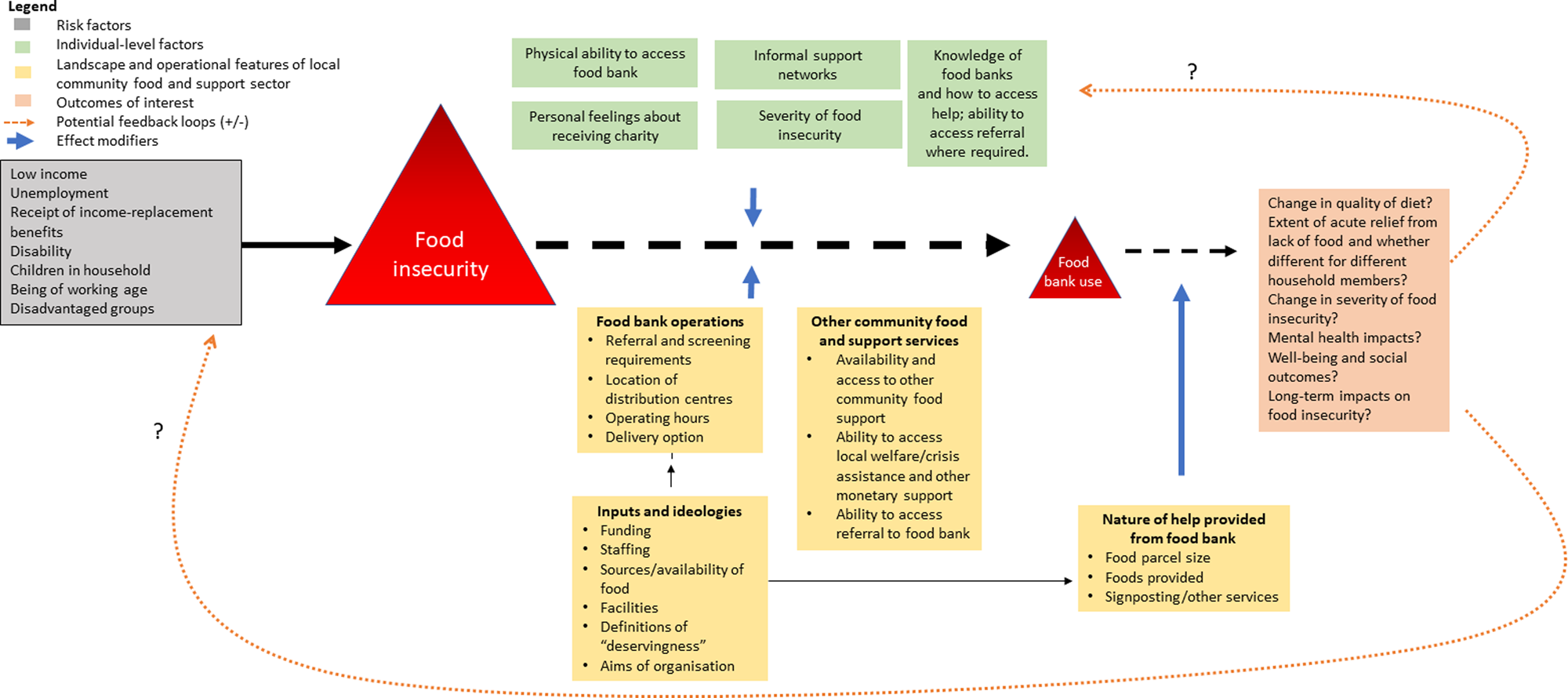

In the next section, we present a framework for understanding the factors influencing the reach of food banks among people experiencing food insecurity and the potential for food banks to have an impact on the food insecurity or nutritional needs of this population.

Conceptual framework: understanding food bank use in the context of food insecurity in the UK

In Fig. 1, we present a novel framework for understanding the discrepancy between food insecurity and food bank use in the UK context, drawing from the academic literature on food insecurity and food bank use from the UK. As already covered, we show known risk factors for food insecurity observed in the UK survey data: low household income, unemployment, receipt of income-replacement benefits, disability, having children in the household, being of working age in comparison to pension age and characteristics often associated with disadvantage, such as single parenthood and belonging to UK-minoritised ethnic groups. The discrepancy between the scale of food insecurity and the scale of food bank use is depicted by the differently sized red triangles.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework for relationship between food insecurity and food bank use within the UK context.

The central arrow shows how it is food insecurity that drives food bank use; however, central to this conceptual framework, we propose that the strength of this relationship, i.e. the likelihood of someone who is food insecure receiving help from a food bank, is impacted by two main groups of factors shown above and below this arrow: (1) individual-level factors relating to the circumstances and feelings about food bank use among people experiencing food insecurity, shown in green; and (2) the landscape and operational features of the local community food and support sector, shown in yellow. In addition, we show potential outcomes of food bank use that we need to better understand in order to understand the relationship between food insecurity and food bank use, namely, whether there are immediate impacts on quality of diet and hunger relief, and longer-term impacts, both positive and negative, that could arise from using food banks. We also indicate that outcomes may differ depending on the nature of the help provided by food banks. Below, we outline the evidence we drew from to develop this conceptual model and where evidence gaps remain.

Individual-level factors influencing the relationship between food insecurity and food bank use

Qualitative studies based on data from food bank users in different places in the UK have described people's feeling about using food banks, highlighting their reluctance to use food charity and resistance to doing so until their circumstances were desperate(Reference Garthwaite57,Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail58) . These studies highlight that feelings of shame have an important role to play, with people describing having to use the food bank as a source of embarrassment and feelings of failure(Reference Garthwaite57–Reference Garthwaite59). This is supported by quantitative evidence showing the high prevalence of severe food insecurity found among food bank users in the UK, suggesting that people have been unlikely to use food banks until they have experienced going without food and have no other alternative(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45,Reference Bramley, Treanor and Sosenko60,Reference Loopstra and Lalor61) .

Access to other forms of informal food and/or financial support from family or friends and religious or cultural communities may also influence who people turn to for help when faced with insufficient access to food. Qualitative research has suggested that people will draw from support networks available to them before turning to charity(Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail58). Surveys of people using Trussell Trust food banks have found that a high proportion of food bank users report having exhausted the option to ask family or friends for help or not having family or friends to ask for help or who are in position to help(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45,Reference Bramley, Treanor and Sosenko60) . Qualitative research among Pakistani women in Bradford found that in contrast to women from White British backgrounds, they were more likely to describe their social and familial networks of support and less likely to report using food banks(Reference Power, Small and Doherty62).

The ability to physically access food banks and bring parcels of food home has also been identified as a barrier to food bank use for some. Though people with disabilities are over-represented in food banks,(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45,Reference Bramley, Treanor and Sosenko60,Reference Loopstra and Lalor61) some qualitative work has documented how people with physical disabilities in particular find it difficult to carry food parcels home(Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra63). This might particularly be an issue for people with disabilities who do not live close to food bank centres, with research showing an association between food bank use and disability rates across local areas in the UK, but that this relationship is attenuated when there are fewer food banks operating in an area(Reference Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Fledderjohann64). Qualitative research by Purdam et al. outlined the personal ‘costs’ to people using food banks, which included long journeys to food banks(Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail58).

Landscape and operational features of local community food and support sector influencing the relationship between food insecurity and food bank use

As shown in Fig. 1, the landscape and operational features that may influence the relationship between food insecurity and food bank use include operational features, and the inputs and ideologies that shape these, and the forms of community food and support services available in a local area.

First, the availability of food banks is key to consider. As food banks are voluntary organisations, it is not guaranteed that there will be a food bank available in every neighbourhood or local area. Some research into where Trussell Trust food banks (the local umbrella organisations, not individual neighbourhood distribution centres) were located in 2016 suggested poor correlation with indicators of risk for food insecurity (e.g. low income, presence of children in household, lone parent household, receipt of benefits)(Reference Smith, Thompson and Harland65). A qualitative study examining the rise of the Trussell Trust network over 2004 to 2011 described their social franchise model and Christian religious beliefs as important drivers of growth, where churches were encouraged to start food banks as part of their social action work, suggesting that this action was not necessarily tied to assessment of need for this provision in local areas(Reference Lambie-Mumford44). An association between the odds of a new Trussell Trust food bank opening and local service spending reductions was observed over 2009–2013, suggesting that food banks might have been opening to fill a gap in local service provision over that period(Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Taylor-Robinson5); however, to our knowledge and likely reflecting that a decision to start food banks originates from individuals or local community organisations or faith groups, there hasn't been a coordinated strategy to ensure food banks are available in all communities across the UK (though mapping availability of access to food banks in local areas has been an area of focus for some local food poverty alliances(66)).

Even when food banks are located in local areas, catchment areas can be large, and food banks may not be located within accessible distance to people's homes, especially in rural areas. May et al.(Reference May, Williams and Cloke67) examined the number of independent and Trussell Trust food bank distribution centres in England and Wales and found that the number of locations people could pick up food from food banks, in mainly largely rural areas, ranged from four locations in Buckinghamshire county to twenty-eight in Durham county, with the density ranging from 1724 people per food bank distribution centre to 62 025 per food bank distribution centre. From qualitative interviews conducted by the same authors, they highlighted that people in rural areas can struggle with the lack of public transportation and high personal transport costs to reach food bank distribution centres and the agencies referring to them.

Similarly, research by Loopstra et al.(Reference Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Fledderjohann64) examined the density of the 1145 Trussell Trust distribution centres operating across England, Wales and Scotland, finding an average of 3⋅43 centres per 100 km2 but that this ranged from a minimum of 0⋅02 sites to a maximum of 27⋅5 sites. In areas served by more centres, there were higher rates of food parcel distribution, suggesting that availability of centres does influence the likelihood of food banks being used. Other research using data from Trussell Trust food banks has also shown a positive relationship between the number of Trussell Trust distribution sites and the numbers of food parcels distributed in postcode districts or local authorities(Reference Sosenko, Bramley and Bhattacharjee41,Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann and Reeves68,Reference Reeves and Loopstra69) . Importantly, the density of food banks has also appeared to modify relationships between risk factors for food insecurity and food bank usage. For example, a positive relationship between disability rates and Trussell Trust food parcel distribution was observed, but this relationship was much weaker in places where there were fewer food banks available(Reference Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Fledderjohann64). Similarly, the number of people experiencing benefits sanctions and numbers of people receiving Universal Credit have both been associated with Trussell Trust food bank use, but these relationships are weaker in places where food banks are less available(Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann and Reeves68,Reference Reeves and Loopstra69) . These findings suggest that for a given level of risk of food insecurity in the population, the extent to which this will be reflected in food bank use depends on the availability of food banks in the area.

Another observed feature of food banks is their limited operating hours. Data from the Trussell Trust network on when their member food banks were open in 2015 showed that fewer than 20 % of food bank distribution sites were open across local authorities in any given hour of the week and that hours of opening were concentrated between 10.00 and 16.00 hours. Among the 257 local authorities with Trussell Trust food banks operating in 2015, only fifty-four (21 %) had food banks that were open on weekends and only 13 % (n 34) had food banks that were open during evenings. There was evidence that there were higher rates of usage where food banks were open for more hours and where they operated on weekends. As with density of food bank sites, there was evidence that more restrictive opening hours weakened relationships between risk factors for food insecurity and rates of food bank usage(Reference Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Fledderjohann64).

A number of other features of how food banks operate could also influence the likelihood of someone receiving help from a food bank, though the quantitative impact on the numbers served has not as yet been documented. The ability of food banks to provide delivery of food parcels may enhance access for people with disabilities or who live in rural areas(Reference May, Williams and Cloke67). During the COVID-19 pandemic, case study research in local authorities across the UK found that a switch to delivery of food parcels was a common adjustment to food bank services during lockdowns(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70). Whilst this was largely viewed as a positive change to enable food parcel access for people unwilling or unable to go out during this period, stakeholders engaged in this research also highlighted that for populations without fixed addresses or unable to make contact to request a delivery, the switch from dropping in when food banks were open to delivery may have been a barrier to receiving food bank food parcels over this period(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70).

Other features of how food banks operate may also influence the extent to which people experiencing food insecurity are able to use food banks. One barrier to use may be the need for a referral from other service organisations. The Trussell Trust model requires that people first receive a referral from a third-party agency, such as Citizen's Advice, a general practitioner office or local council, before they are able to receive a food parcel from a food bank. Among independent food banks, a similar model is also often used: the aforementioned survey of independent food banks found that about 60 % had a referral system in place(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). Among those who did not require a third-party referral, other measures were often in place to check identification and/or assess need, such as checking IDs, requiring a registration form to be filled or a needs assessment questionnaire or interview. The need for a referral from a third-party agency in Trussell Trust food banks in particular may mean that food banks are more likely to serve people who interact with referring agencies than people who do not. Whilst qualitative and quantitative research suggests food bank managers and volunteers may at times relax referral requirements(Reference Williams, Cloke and May71,Reference Power, Doherty and Small72) , even the perception of the need for a referral may put people off seeking assistance. Further, the criteria that referral agents apply when deciding who to give a food bank referral to may differ across referral agents. To our knowledge, differences in referral practices have not been charted in the UK, even though these are key gatekeepers to food bank access.

The spaces, and inadequacy of space, that food banks have to operate in may also be a barrier to use. Many food banks are affiliated with particular faith groups and operate within faith-based settings such as churches or mosques(Reference Power, Doherty and Small72). Among independent food banks, just under half operated in faith-affiliated buildings(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4); the Trussell Trust also started as a Christian-faith based organisation, with many food banks operating from churches(Reference Lambie-Mumford44). For people of no faith or different faiths, this might be a barrier to using these food banks. Because food banks often also rely on shared premises, they might not be conducive to privacy. In the survey of independent food banks, over 20 % reported not having space that allowed privacy for their clients(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). Qualitative research among people using food banks highlighted a story from one participant who shared how the fact that the food bank had a glass-fronted waiting room was a barrier to going in, as he did not want to be seen using the food bank(Reference Moraes, McEachern and Gibbons73).

With exception to the examples already provided, there has been little examination of the extent to which the operational characteristics of food banks in a local area influence who among people experiencing food insecurity reach food banks. However, the profile of people using food banks shows that people out-of-work and in receipt of benefits are over-represented(Reference Sosenko, Littlewood and Bramley45,Reference Bramley, Treanor and Sosenko60) . Whilst these are risk factors of severe food insecurity, and therefore drivers of food bank use in their own right, people without work may also be more able to access food banks in the hours when they are open, and people in receipt of benefits may be more likely to be connected to agencies that can provide referrals. For example, among independent food banks, about 70 % indicated that Jobcentre Plus offices were referral agents(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4), which predominantly interact with people who are unemployed or underemployed and in receipt of benefits in the UK.

In the present conceptual framework (Fig. 1), we also indicate higher level determinants of the ways that food banks operate. These include the financial and in-kind resources that shape their operational capacity and an organisation's ideologies. The availability of staff or volunteers, the amount of funding and food donations received, the availability of transport vehicles and the availability of facilities for storing food are all likely influence on how frequently food banks are open, where they operate and limits and restrictions they place on accessing food. In a survey of independent food banks operating in England over 2018–2019, 47 % of food banks had no paid staff, and where staff were employed, the majority were part-time(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). Each week, 75 % of food banks relied on five or more volunteers, with 21 % relying on twenty or more volunteers. This reliance may limit the capacity of food banks to run on a day to day and week by week basis, but it is also a key vulnerability in the system to shocks. For example, when cases of COVID-19 began spreading in the UK in March 2020, resulting in warnings for clinically vulnerable groups to stay at home and not leave home for any reason, many food bank volunteers were not able to continue working in food banks, as the volunteer profile was typically older people, who were at higher risk of illness from COVID-19(Reference Power, Doherty and Pybus74). Many food banks had to rapidly find new volunteers to meet increasing demand at that time(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70).

Different ideologies in terms of ‘deservingness’, fear of people becoming dependent on food bank support and/or whether an organisation views their service as only for people in acute financial emergencies or as a regular form of support to supplement chronic low incomes, may also shape how food banks operate, for example by limiting access to how many times people can receive a referral to a food bank or by setting eligibility criteria(Reference Williams, Cloke and May71,Reference Lambie-Mumford75) .

It is also important to note here that all food banks will have their own ways of working ‘on the ground’. This variation is often overlooked, with food banks often being considered as homogeneous entities in the UK. In reality, their operational differences may mean very different patterns of use in different places (and different outcomes, as discussed later).

Alongside the provision of food parcels from food banks, there is a much wider landscape of third-sector and statutory organisations that form the local community food and support sector; these organisations also aim to increase access to food for low-income people in local areas. As already highlighted, some projects have a long-standing history in the UK, such as the provision of meals through ‘soup kitchens’(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti22). In recent years, new models of food projects have been rolled out, such as social supermarkets (also known as food pantries or food clubs(Reference Saxena and Tornaghi76,Reference Maynard and Tweedie77) ). These are often membership based and provide access to groceries and other essentials for a low membership fee. One study conducted in Bradford, which involved mapping ‘community food assets’ in 2015, documented a range of activities undertaken by sixty-seven community food organisations, all aimed at increasing access to food(Reference Power, Doherty and Small72). These variously included food growing projects, social supermarkets, community centres providing low-cost meals and food box schemes. Case studies of local responses to concerns about food insecurity over the COVID-19 pandemic also documented a wide range of food provisioning activities in local areas(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70).

A key question is how other types of food projects impact who seeks help from food banks when facing food insecurity. Some projects are not targeted to help people facing an acute need for food, such as food growing projects. However, many food projects suggest they are an alternative to food banks, emphasising participatory elements such as operating a membership and providing social benefits alongside the provision of food(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70,Reference Moraes, McEachern and Gibbons73) . However, to our knowledge, potential differences and overlaps between people receiving help from food banks and using other forms of food provision has not been charted in the UK. Nonetheless, the wider landscape of agencies engaged in activities targeted towards enhancing food access for low-income people might be a factor influencing food bank use.

Alongside the availability of community food programmes, local authorities may also play a role in responding to acute financial hardship and in turn, food insecurity, in their populations. In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, local authorities administer emergency financial schemes, grants provided to people in acute financial need(Reference Nichols and Donovan78). In the past, a similar scheme operated according to a similar model in England, but after 2013, local welfare assistance was devolved to local governments. As a result, a myriad of local welfare assistance schemes now exist across England; although in about one in four local authorities, there is none(Reference Nichols and Donovan78). Some councils provide cash grants or offer vouchers for food, but others use their funds to support local third-sector organisations, such as food banks, and in turn, provide referrals to food banks as their response to people facing insufficient financial access to food. Because local authorities are under no obligation to monitor their schemes or keep data on who receives support or what types of support is provided, there is little evidence of the impact of various types of schemes on food insecurity, and in turn, food bank use. However, we would hypothesise that in places where a local authority provides a ‘cash-first’ approach, referring to an approach advocated by IFAN for local authorities to provide cash grants to people in financial crisis and advice on financial support available in place of, or alongside, referrals to a food bank(79), people who are facing food insecurity may be less likely to use a food bank; in comparison, where local authorities offer food bank referrals in response to someone presenting in acute financial difficulty rather than a cash first approach, food bank use may be more likely. Indeed, a recent pilot of a cash grant programme in Leeds, UK, which provided people in financial need with cash grants found that the majority did not use a food bank whilst they were receiving grant instalments(80).

As already highlighted, access to food banks may also be impacted by the nature and number of local support agencies in a local area who act as gatekeepers to food banks where referrals to food banks are required. During the COVID-19 crisis for example, case study research found that some food banks experienced a decline in referrals because their referral partners were no longer seeing clients and were not then able to provide referrals(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Gordon and Loopstra70).

Potential outcomes of food bank use

Compared to studies in other country contexts, published academic research on the nutritional quality and quantity of food provided from food banks in the UK context is minimal(Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt11), as are data on the impacts on diets among people receiving help from food banks. One study has examined the contents of food parcels for a single adult across two Trussell Trust food banks and nine independent food banks operating in Oxfordshire, finding that when compared to nutrition and energy requirements for a 3-d period, food parcels provided more than what is needed for macronutrients and most micronutrients, with the exception of vitamins A and D(Reference Fallaize, Newlove and White81). Very similar results were found in an analysis of food parcels from Trussell Trust food banks operating in London, which used a similar approach(Reference Hughes and Prayogo82). The study from Oxfordshire suggested that food banks in the study provided very different amounts in their food parcels, with some providing enough food to past 9 d. This finding aligns with a survey of independent food banks, which found that about 45 % of food banks aimed to provide food for 4 d or more(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4).

Importantly, however, food banks are limited in their ability to follow nutritional guidelines and meet the cultural and health needs of the people who they serve(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4,Reference Thompson, Smith and Cummins83) . There is also a lack of evidence tracking how foods from food banks are used and consumed by the households receiving them. Though studies may find food parcels lacking in some nutrients and abundant in less healthy foods, the impacts of these observations on diets depend on how foods are distributed to different household members and the time frame over which they are consumed. Importantly, any influence food banks have on the diets of people using them is going to be bound by how often people can access their support. In the past, the Trussell Trust had a guideline in place that suggested people shouldn't receive more than three food parcels without an intervention from the food bank to then identify why another referral was necessary(Reference Lambie-Mumford44). Administrative data from the Trussell Trust used to identify unique households using their food banks over 2019–2020 found that on average, households received a food parcel from a Trussell Trust food bank 2⋅2 times in a year, with 57 % only receiving a food parcel once and only 10 % receiving a food parcel four or more times(Reference Bramley, Treanor and Sosenko60). Among independent food banks operating in 2018–2019, a survey revealed that whilst about 44 % placed no limits on how often people could receive a food parcel, about 30 % restricted use to six or fewer parcels per year(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). With food banks being accessed so infrequently by the majority of people using them, the impacts of food bank provision on diets in the population is likely to be minimal.

Beyond meeting nutritional needs, there are also important questions about whether food banks can provide foods appropriate for a variety of cultural and health needs. A qualitative study of people using food banks in Stockton-on-Tees highlighted that people with digestive problems particularly struggled with the foods they received from food banks, which were not tailored to their dietary needs(Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra63). Although study findings show that people using food banks often express gratitude for the food they receive, at the same time as being grateful, participants also express costs to their mental health of receiving food charity, physical discomfort when having to carry a quantity of foods home over a long distance and costs to their health due to consuming foods that are ill-matched to their preferences and needs(Reference Garthwaite, Collins and Bambra63).

Quantitative data on the dietary impacts of receiving food bank food parcels and measures of severe food insecurity following food bank use are lacking in the UK context. Thus, in the present conceptual model (Fig. 1), we highlight that immediate impacts on diets and relief from hunger are unknown. We also suggest a potential feedback loop: improvements in dietary quality and relief from hunger resulting from food bank use may influence the likelihood that an individual would return to a food bank when experiencing food insecurity in the future. However, the lack of these positive outcomes may also influence the likelihood of people continuing to use food banks in that if people do not experience enough or any benefit, they may not view the use of food banks as worth their while.

Beyond short-term impacts (i.e. immediately following receipt of help from a food bank), there is little to suggest that food bank use has a long-term impact on food insecurity, as most people using food banks are severely and chronically food insecure(Reference Loopstra and Lalor61). However, the nature of wrap-around support offered by many food banks may have the potential to reduce food insecurity among those receiving assistance from them. Food banks are often engaged in providing a range of services, including signposting, advocacy on behalf of clients, benefits advice, debt advice, housing advice and community cafes(Reference Loopstra, Goodwin and Goldberg4). However, the impact of this additional support on long-term food insecurity outcomes has not yet been evaluated.

Role of food banks into the future

In October 2022, a press release from IFAN reported on new survey collected from their members, which indicated that among the 188 independent food banks surveyed, 24 % reported reducing the size of the food parcels they distributed because they did not have sufficient supplies of food to meet the demand they were experiencing in recent months due to rising demand attributed to rising costs of living(84). A clear message that food banks were struggling to cope was contained in the press release, with reports that food banks were deeply concerned they would not be able to meet escalating demand through the winter. A similar message has been recently released in a press release from the Trussell Trust(85).

These stark messages from food bank providers raise questions about the role of food banks into the future. The Trussell Trust and IFAN and their members regularly campaign for interventions that will increase incomes in line with the cost of living and call for the end of the need for food banks. The need for these types of interventions is also underscored by the fact that food banks reach only a fraction of people who experience food insecurity in the population. Population-based policies are needed. As shown, food banks are inherently constrained in their capacity to respond to the level of need in the population, but also lie outside societal norms for how people should be able to acquire food in the UK context. Here, we return to the definition for food insecurity(Reference Anderson86), which includes ‘uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways’ as part of the experience of food insecurity. As reflected in qualitative research on food banks, food banks are clearly not a socially acceptable way of acquiring food. Academics have long voiced concerns that the existence of food banks in high-income countries serves to give the impression of meeting the needs of the population and allows governments to turn away from their responsibilities to ensure that their populations can afford and access sufficient food(Reference Tarasuk and Davis1,Reference Poppendieck2,Reference Riches and Ismael87,Reference Riches88) . Thus, as we look to the future of food banks in the UK, it is hoped that their role in food insecure populations will be to advocate for the upstream polices that will make them obsolete, rather than give the impression that they are an available and sufficient form of support for people facing food insecurity. In light of the evidence presented here that food banks neither reach a majority of people experiencing food insecurity, nor have capacity to increase provision or reach to ensure food needs are met, and that among those using them, food insecurity remains, there is clearly a need for different interventions to this critical public health problem.

Financial Support

Both authors were supported by the Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/V009869/1.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

Both authors contributed to the conceptual development of the present paper. R. L. wrote the first draft and both authors made significant contributions to writing of the subsequent drafts.