Although most studies in the field of trauma relate to the psychological effect of potentially traumatic events (PTEs), such as post-traumatic stress disorder, fewer studies focus on the PTEs themselves. Commonly referred to as any event that is considered psychologically overwhelming for an individual and occurs outside ‘normal’ human experience,Reference Briere and Scott1 exposure to PTEs is fairly common globally.Reference Benjet, Bromet, Karam, Kessler, Mclaughlin and Ruscio2 Although common, types and prevalence of PTEs differ greatly across populations and countries. Studies have indicated varying population prevalence of trauma exposure per country, ranging from 29% in Bulgaria to 83% in Peru.Reference Benjet, Bromet, Karam, Kessler, Mclaughlin and Ruscio2 Although trauma exposure disproportionately affects populations of lower socioeconomic status,Reference Jarl, Cantor-Graae, Chak, Sunbaunat and Larsson3 most epidemiological studies on trauma exposure focus on populations in high-income countries.Reference Kilpatrick, Resnick, Milanak, Miller, Keyes and Friedman4

Trauma exposure in homeless people with severe mental illness

One population that is particularly vulnerable to trauma exposure is homeless people with severe mental illness (SMI). First, a wide range of PTEs have been linked to homelessness, including domestic violence, sexual abuse, physical abuse, war and natural disasters.Reference Hopper, Bassuk and Olivet5,Reference Kim, Ford, Howard and Bradford6 Additionally, there is substantial evidence indicating that people with SMI are more susceptible to trauma exposure than the general population.Reference Grubaugh, Zinzow, Paul, Egede and Frueh7 For example, in the USA, a cohort of 275 patients with SMI had a 98% prevalence of lifetime exposure to traumatic experiences.Reference Mueser, Trumbetta, Rosenberg, Vidaver, Goodman and Osher8 Apart from high rates of reported sexual or physical abuse and exposure to interpersonal violence, people with SMI also report the development of SMI and the experience of hospitalisation as traumatic experiences.Reference Mueser, Rosenberg, Goodman and Trumbetta9 The complex nexus between homelessness and SMI make investigating trauma in this population with multiple vulnerabilities a matter of urgency.

Homelessness and SMI in India

According to a 2011 census, the population of homeless individuals living in India was reported at approximately 1.8 million;Reference Sattar10,Reference Kumuda11 however, this number is said to be a gross underestimation, with other records reporting numbers as high as 78 million.Reference Sattar10 With up to 40% of homeless people reported to suffer from SMI,Reference Toro12 this accounts for a largely neglected subdivision of the population that remains particularly vulnerable to traumatic experiences. To determine the magnitude of trauma exposure in populations of homeless people with SMI in India, there is a need for the adaptation and development of tools to accurately identify PTEs in a manner that is both relevant and culturally sensitive to the needs of the target population.

Trauma inventory

Originally developed for use in psychosocial research projects, the Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) is one such tool that has been one of the most widely used traumatic event inventories available.Reference Hooper, Stockton, Krupnick and Green13 The 25-item self-reported assessment examines lifetime exposure to PTEs grouped into three main domains: crime-related events (4 items), general disaster and trauma (13 items), physical and sexual experiences (7 items) and other events (1 item). Each item is prompted by a no/yes response, followed by the number of times and approximate age at which each event occurred, if a yes was indicated. Respondents are also prompted to specify details of the event and their relationship to those involved, where appropriate. The tool's use of neutral behavioural language and its structured no/yes response as opposed to open-question format has made it particularly useful for health researchers and care providers in diverse settings. The THQ is intended to gather information concerning the lifetime history of trauma exposure from general, community and clinical populations,Reference Hooper, Stockton, Krupnick and Green13 and has been used in a diverse range of populations and settings, including trauma exposure in populations experiencing SMI,Reference Shannon, Maguire, Anderson, Meenagh and Mulholland14 the impact of childhood trauma on psychosis in China,Reference Sun, Zhang, Guo, Hu, Li and Mwansisya15 and trauma exposure in a rural primary care setting in South Africa.Reference Peltzer, Seakamela, Manganye, Mamiane, Motsei and Mathebula16

Problem statement and study aims

Scholars have called into question the cross-cultural validity of the construct of trauma in settings outside of the original construct's Western origin, expressing that if the concept of trauma is intended to describe a situation that is outside the norm of human experience, then this norm is highly subjective to the cultural context in which trauma is being explored.Reference Patel17 As the DSM exclusively considers events to be traumatic if they are life-threatening or jeopardise one's physical integrity, there is ongoing debate as to whether this classification of a traumatic event is appropriate, or whether it underestimates the true extent of trauma exposure in different populations.Reference Briere and Scott1,Reference Jones and Cureton18 Although there is record of the THQ's application in various cultural contexts, there is very limited published record of its cultural adaptation for use in different cultural contexts.Reference Fiszman, Cabizuca, Lanfredi and Figueira19 Therefore, the aim of this study is to contribute to the applicability of trauma inventories in a population of homeless people with SMI in Tamil Nadu, India, by translating and culturally adapting the THQ for use in this population. Additionally, it explores the theoretical implications of the study's findings on the construct of trauma, sheds light on patient and provider perspectives on trauma assessment, and introduces the moral debate of asking culturally sensitive questions.

Method

Design

To determine the cross-cultural validity of the THQ for use in a population of homeless people with SMI in Tamil Nadu, India, a qualitative approach was taken, consisting of a number of translation exercises, focus group discussions and expert consultations. Several studies have demonstrated the added value of applying qualitative methods as a means to successfully culturally validate a variety of measurement instruments.Reference Fiszman, Cabizuca, Lanfredi and Figueira19,Reference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia20

Approach to inquiry

This study takes both an emic and constructivist approach to the investigation of trauma in the context of homelessness and SMI in Tamil Nadu, India, which considers both group and individually influenced nuances that may shape the experience of trauma, respectively. First, several studies have highlighted the issue of applying methods for identifying and treating trauma that have been based on observations made in Europe and North America to low- and middle-income countries, where experiences are almost certainly shaped by local context.Reference Jones and Cureton18,Reference Gilmoor, Vallath, Regeer and Bunders21,Reference Rasmussen, Keatley and Joscelyne22 Inspired by this, the present study is informed by an emic approach, in which research efforts are focused on understanding local understanding and experiences of trauma, to better inform practice and research. Second, this study adopts a constructivist approach, which posits that the construct of reality is subjective and shaped by the norms, customs and values of the individual.Reference Schwandt, Denzin and Lincoln23 In this context, a constructivist considers a traumatic experience to be subjective, and influenced by the sociocultural and political context in which the experience is had.Reference Patel17

Researcher reflexivity

Author A.R.G. is a global mental health researcher currently pursuing his doctoral degree in The Netherlands. Although none of the research participants know the principal investigator personally, his extended presence and active participation in the daily happenings within the non-governmental organisation for up to 9 months before data collection made him a familiar face among participants. S.V. is a local, practicing clinical psychologist with 3 years of experience working with this specific population before data collection, and is well-versed in the local language. Her extensive theoretical and contextual knowledge, as well as experience, enriched the data collection process. Any potential sources of bias and data misinterpretation were extensively discussed among authors A.R.G., S.V. and D.v.d.B. during data collection and analysis.

Setting

This study took place in the Kanchipuram and Chennai districts of Tamil Nadu, located on the south-eastern coast of India, along the Bay of Bengal. Attributed to its geographical positioning and low-resourced surrounding rural settlements, the city of Chennai has one of the highest population densities of urban homeless in India,Reference Kumuda11 with as many as 40 000 homeless individuals reported.Reference Sattar10

Participants and recruitment

Mental health professionals (MHPs) and user-survivors were recruited for participation in this study from within The Banyan network of care – a local, non-profit, non-governmental organisation, that caters to over 3000 homeless individuals and serves approximately 1 million people with mental health challenges across India, in a diverse network of mental health services. The term user-survivors is used to describe homeless people or those at risk of homelessness who have been diagnosed with SMI, and make use of The Banyan services in a long-term, short-term, in-patient or out-patient capacity. To account for potential differences among user-survivors, participants were recruited from a variety of The Banyan services. User-survivors who were intellectually disabled or perceived to be too symptomatic to comprehend the instructions of the focus group discussions were excluded from participation.

To gain a broad range of perspectives, a diverse sample of MHPs of varying mental health professions, including psychology, psychiatry and social work, were recruited. Most MHPs were fluent in both Tamil and English, and had been mental health practitioners within The Banyan for a minimum of 2 years.

Data collection

Data collection took place in three different phases of work.

Phase 1: tool adaptation

Phase 1 was part of a larger project, the findings of which are published elsewhere.Reference Gilmoor, Vallath, Regeer and Bunders21 In short, a series of free-listing exercises and in-depth interviews with 26 user-survivors were used to identify PTEs that were relevant to people who were homeless, or at risk of homelessness, and living with mental illness in Tamil Nadu. User-survivors were asked to describe what they understood to be trauma (adirchi in Tamil), and list as many events as possible that they had either experienced or considered to be traumatic. Analysis of the interview transcripts generated a composite list of events perceived to be traumatic by user-survivors. The first author then cross-referenced this list to the 24 existing PTEs listed in the original THQ. Items that were not found to be relevant to the local context were removed from the original scale, and additional items thought to be relevant were added.

Phase 2: translation

The tool was translated using the translation and back-translation approach as described by Gudmundsson (2009).Reference Gudmundsson24 The adapted THQ was first translated into Tamil (T1) by an English–Tamil bilingual professional medical transcriptionist, who has extensive experience in translation and transcription work in both languages. Using four blinded translators of varying professional backgrounds, T1 was then independently back-translated into English (BT1, BT2, BT3 and BT4). A multidisciplinary team of experts, consisting of a bilingual clinical psychologist, a bilingual social worker, and English-speaking principal investigator and co-researcher, was then consulted and incorporated the feedback into a newly adapted THQ (THQT2).

Phase 3: cognitive testing and cross-cultural adaptation

Next, a series of six focus group discussions were used to test and further develop the THQT2 by evaluating how the target population understands and responds to the questionnaire. This qualitative approach was employed to ensure an in-depth exploration of participants’ views on specific aspects of the questionnaire. Four focus group discussions consisted of five, seven, five and three female user-survivors, respectively. At the time of recruitment, there were no potential male user-survivor participants that met the inclusion criteria of illness stabilisation and reduction in symptoms since beginning treatment at The Banyan. Two additional focus group discussions consisted of MHPs, with one group recruited for their language expertise as first-language Tamil speakers (n = 5), and another for their experience in care provision within The Banyan (n = 6). Details of the study sample recruited for the focus group discussions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Study sample characteristics

CGH, Clustered Group Home; ECRC, Emergency Care and Recovery Center; HSS, Housing with Supportive Services.

The design of the focus group discussions were based on Herdman et al's model for assessing cross-cultural equivalence in health-related quality of life questionnaires,Reference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia25 which draws from extensive research in cross-cultural work on health-related quality-of-life studies. Based on six aspects of equivalence needed to be achieved to determine a tool's cross-cultural validity (conceptual equivalence, semantic equivalence, item equivalence, operational equivalence, measurement equivalence and functional equivalence), this framework has been successfully applied in a number of other cross-cultural tool development studies.Reference Fiszman, Cabizuca, Lanfredi and Figueira19,Reference Dadun, Van Brakel, Lusli, Damayanti and Bunders26–Reference Stevelink, van Brakel and Augustine28 Because of the subjective nature of trauma and the THQ's function as an inventory, the scope of this study was limited to the first four types of equivalences. The definition and operationalisation of the types of equivalence used in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Description of the different categories of equivalence used in this study, as described by Herdman et alReference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia25

THQ, Trauma History Questionnaire; THQT2, second revision of the adapted Trauma History Questionnaire.

All focus group discussion participants were first instructed to complete the THQT2. Next, a series of questions reflecting Herdman et al's modelReference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia25 were addressed during the group discussion. Conceptual and item equivalence were addressed by examining which of the seven domains and 37 items of the THQT2 were relevant to user-survivors. The group also discussed what other traumas should be listed, and what items they felt were either inappropriate or not applicable. Semantic equivalence was evaluated by cognitive assessment. Participants were instructed to read each item and then share its interpreted meaning with the rest of the group. In this way, the readability and clarity of each item and the overall tool was assessed. Operational equivalence was addressed by discussing advantages and disadvantages of self-administration and rater administration. Any errors, misunderstood item/terms or unclear elements of the THQT2 were also addressed.

Finalising the THQ

All focus group discussion notes and transcripts were examined by a multidisciplinary team of professionals, consisting of a global health researcher, a clinical psychologist and a social worker. Using this feedback, the THQT2 was once again modified, translated and back-translated to develop the THQT3. A final team of experts, consisting of two clinical psychologists, a social worker, a counselling therapist, a psychiatrist and the principal investigator, reviewed the latest version. Final recommendations were consolidated and incorporated into a new version of the adapted THQ: the THQ for Multiple Vulnerabilities (THQMV), ready to be piloted (see Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.952).

Analysis

A directed-content analysis approach, as described by Hsieh and Shannon,Reference Hsieh and Shannon29 was undertaken for analysis. First, all digitally recorded focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim and translated to English. All transcripts, notes and further documentation of the changes made to the original THQ, THQT1, THQT2 and THQT3 were studied for familiarisation of the data. Using Herdman et al's model for cultural equivalence,Reference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia25 a deductive approach was taken for analysis. Additional codes were created to account for important aspects of the data that did not fit any of the predefined codes. Excerpts tagged with the same codes were consolidated and examined for higher-level analysis.

For quality assurance, all transcripts were independently coded and analysed by authors A.R.G. and D.v.d.B. To test for inter-coder reliability, two randomly selected transcripts were additionally coded and analysed by author S.V. and compared with the coded transcripts of A.R.G. The number of agreed upon codes as a percentage of the total number of codes identified was used to determine inter-coder reliability, for which a score of 75% agreement was deemed as acceptable. Any divergence in interpretation of the data was discussed until consensus was achieved.

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Dutch Science Committee of the Institute for Health and Care Research (EMGO+) (approval number WC2015-049 HZ) and The Banyan Internal Ethics Committee in Chennai.

Consent statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all patients. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded by authors A.R.G. and S.V..

Results

Findings suggest that extensive modifications to the THQ were needed to achieve cultural equivalence for use in the target population.

Conceptual equivalence

Trauma domains

Based on the free-listing exercises conducted, user-survivors recognised three domains of traumatic experiences – namely, ‘mental health experiences’, ‘homeless experiences’ and ‘relationship issues’ – in addition to the four domains listed in the original THQ. For mental health experiences, user-survivors considered the development of their mental illness, associated stigma and negative health experiences as conceivably traumatic (Table 3, quote 1). Experiences of a lack of basic necessities, a lack of security, and abandonment were homeless experiences commonly reported as traumatic by user-survivors (Table 3, quote 2). Finally, events such as divorce or abandonment by a family member were commonly considered plausibly traumatic experiences related to relationship issues (Table 3, quotes 3 and 4). Feelings of a lack of representation of these three domains, and particularly of homeless experiences, were shared in the focus group discussion conducted with MHPs (Table 3, quote 5). Based on the insights and feedback of both user-survivor and MHP groups, the additional trauma domains of mental health experiences, homeless experiences and relationship issues were added to the THQ.

Table 3 Additional trauma domains as recommended by participants

Item equivalence

Item relevance

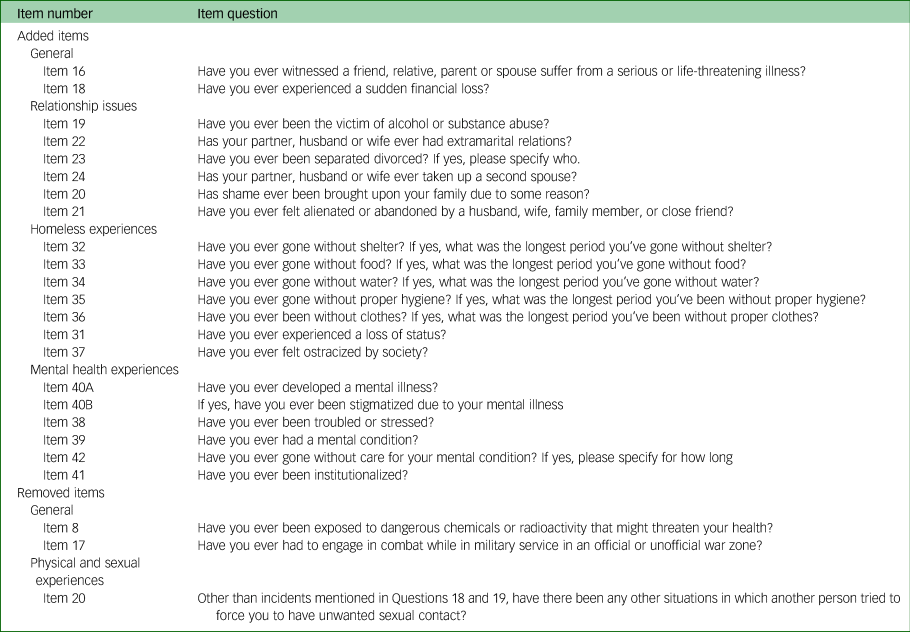

In total, three items were dropped and 21 items were added to the THQ to achieve item equivalence in the adapted THQT2 (Table 4). Two of the items deemed irrelevant to the target population dealt with exposure to hazardous chemicals and engagement in politically driven conflict, as no user-survivors reported such incidents occurring in this population. A third item, addressing the culturally sensitive topic of rape, was deemed too intrusive in its current form.

Table 4 Overview of items added and removed from the Trauma History Questionnaire for item equivalence

The 21 added items mainly contribute to the added trauma domains of homeless experiences (n = 7), mental health experiences (n = 6) and relationship issues (n = 6). Two items were additionally added to the domain of general disasters and trauma. There was unanimous agreement across all stakeholder groups that the types of traumatic experiences listed in the THQT2 were indeed relevant to the intended target population.

Although universally applicable according to the majority of respondents, there was general consensus among MHPs that items could be further specified to specifically fit the Indian context (Table 5, quotes 1 and 2).

Table 5 Overview of item amendment for cultural relevance

THQT4, fourth revision of the adapted Trauma History Questionnaire; THQT2, second revision of the adapted Trauma History Questionnaire.

Tool and item acceptability

Although there were some instances of rehashing some negative memories that were emotionally arousing, the general reception and acceptability of the THQT2 was positive. User-survivors expressed that the inventory provided a form of release, providing a sense of relief and even joy (Table 6, quotes 3 and 4).

Table 6 Item equivalence and acceptability

FGD, focus group discussion.

With one exception, all items were deemed acceptable by the user-survivor participants. However, it was unanimously agreed that item 20 (‘Has anyone ever touched private parts of your body, or made you touch theirs, under force or threat?’) was considered too offensive and not socially acceptable to be asked in its current form (Table 6, quotes 5–7). This item was later adapted in the subsequent version of the THQT4 to ‘Has anyone ever touched you or made you touch them inappropriately, under force or threat?’. There were a number of MHPs who felt that specifying the relationship between victim and perpetrator in a number of the items listed was invasive, and questioned its added relevance to the inventory (Table 6, quote 8). However, these views were not shared by the target population, and so were not incorporated.

Semantic equivalence

Referential equivalence

To achieve referential equivalence, several recommendations were made by the language experts (Table 7). The term bodhai pural, for example, specifically translates to ‘drug addiction’ in Tamil, excluding other forms of possible addiction. This was later changed to ‘bodhai sambandham adimai’, which translates to substance-related addiction, to capture the intended referential meaning of substance misuse. Interestingly, no Tamil translation could be found for the term ‘stigma’. Based on deliberations with the language experts, the Tamil word for shame (kalangam) was used to refer to stigma, as it was found to be the closest match for the semantic meaning of stigma.

Table 7 Semantic equivalence

Bolding in the item question indicates the specific word/phrase that was altered.

Connotative equivalence

A few adaptations for connotative equivalence were also necessary (Table 7). Both user-survivors and MHPs indicated that the term ‘adultery’ has a very specific negative connotation, as it directly translates to prostitution (vibachaarathil). After several deliberations, the term was replaced with ‘extramarital affair’ (thirumanairthuku apparpathu kuruvu) in an effort to maintain scale neutrality. The item ‘Have you ever developed a mental illness?’, although grammatically correct, was understood to be too confrontational because of the negative connotation of ‘illness’. As recommended, the term mental illness (mana noyinaal) was rephrased as mental health problem (mana nala badhipu).

Operational equivalence

Mode of administration

The THQT2 could only be self-administered by 5 out of the 20 user-survivors who participated in the initial pilot. The remaining 15 were rater-administered, either because they were unable to read or write in Tamil, or were physically impaired. Despite the need for assistance, all user-survivors in the pilot unanimously agreed that they preferred to complete the inventory on their own, reporting that it allowed them to exercise their individual autonomy and gave them a sense of pride and empowerment (Table 8, quote 1). Contrasted to user-survivors’ views, several MHPs firmly believed that, because of their condition and to eliminate bias and maintain accuracy, the adapted THQ should be strictly rater-administered (Table 8, quote 2). Other MHPs were less adamant on this issue. Although they generally believed that the inventory should not be entirely self-administered, they did acknowledge user-survivors’ appeal for autonomy. A compromise was decided in which a rater should be present for questions and assistance.

Table 8 Operational equivalence

FGD, focus group discussion; EMDR, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.

Inventory format

Overall, user-survivors and MHPs were satisfied with the format of the inventory. Several MHPs, however, felt that the present order in which the trauma domains and items were presented was too intrusive (Table 8, quote 3). For user-survivors to feel more comfortable and build up a tolerance to the potential offensiveness of the items addressed, we changed the order of presentation of domains by moving ‘physical and sexual experiences’ to after ‘relationship issues’, starting with items that are perceived as less intrusive, such as shame and alienation, to the more intrusive items of physical abuse, humiliation and sexual assault.

Measurement of trauma

Despite the need for initial clarification of the instructions, user-survivors were able to successfully meet the requirements of measuring trauma as prescribed by the original THQ. They were able to indicate whether they had experienced PTEs in the THQT2 and were able to identify the number of times and age at which the traumatic event has occurred. A few MHP respondents, however, questioned the accuracy with which user-survivors are capable of achieving the latter. Additionally, user-survivors unanimously felt that if administered to symptomatic patients with mental illness, they would not be able to comprehend the inventory or endure its entire duration (Table 8, quotes 4 and 5).

In addition to the measures of trauma prescribed by the original THQ, MHPs reported wanting a rating of trauma severity, where user-survivors would be instructed to rate their experience of trauma from 1 to 5, in terms of distress experienced. MHPs felt that this was a contextual adaptation that was needed to allow practitioners to prioritise specific events for intervention in instances where multiple traumas are evident.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal three major points of reflection, which are described below.

The construct of trauma has both generic and culturally specific elements

Our study reveals that in this particular population, there are aspects of trauma that are recognised as universal across all contexts and those that are unique to the context of homelessness and SMI in Tamil Nadu, India. Starting with generic elements, results indicate that the three trauma domains (crime-related events, general disasters and trauma, and physical and sexual experiences) represented in the original THQ were all recognised by the target population as traumatic types of events. These trauma domains, which are based on a model of eight generic stressor dimensions of trauma by Green,Reference Green30 cover a wide range of events, primarily chosen because they have been historically considered important by clinicians and clinical researchers.

On the other hand, the items on the original THQ do not fully represent the experiences and perceptions of the target population, as it fails to capture experiences specific to homelessness, SMI and relationship issues – experiences regarded as conceivably traumatic in this population. Although PTEs are outside the realm of normal human experience, culture dictates what is normal and what is abnormal. Taking the example of the item divorce: with 40% of all marriages ending in divorce,Reference Kennedy and Ruggles31 the dissolution of marriage is a fairly normalised event in the USA, but, despite being on the rise in India in recent years, divorce rates are comparatively low at 0.24%, as reported in a 2011 census.Reference Crawshaw, Auyeung, Norton and Weinman32 Divorce in India is conceivably distressing, particularly for women, who may experience a substantial decline in standard of living and are often subjected to disapproval from family members and the community.Reference Amato and Kurian33 Events such as rejection and abandonment, again, are conceivably distressing to anyone experiencing it; however, in a collectivist society such as in India, where social cohesion and interdependence are not only the norm, but also a lifeline for many households,Reference Chadda and Deb34 these experiences can have devastating effects on the well-being and psyche of many individuals.

There is significant divergence in views on tool acceptability between user-survivors and MHPs

It appears that MHPs and user-survivors have very different views on the acceptability of the THQ and its usefulness in clinical practice. Results revealed user-survivors to be more receptive of the adapted THQ, whereas MHPs remained critical. On the one hand, MHPs view the use of such trauma inventories in clinical practice as an impersonal and insensitive approach to obtaining the trauma histories of their patients. Contrarily, findings also show that user-survivors endorse the use of such inventories, feeling that their experiences have been recognised and their impact acknowledged. These findings on user-survivors’ experiences with tool administration are consistent with previous studies, such as that conducted by Carlson et al in a population of 223 psychiatric in-patients,Reference Carlson, Newman, Daniels, Armstrong, Roth and Loewenstein35 but available literature on this topic is scarce.

Resistance to tool implementation by MHPs can be because of a number of reasons. First, MHPs perceptions that administering the adapted THQ may be distressing to their patients reveal a level of protectiveness over their well-being. However, overprotection can be a sign of underestimating patient capabilities and a hindrance to care. Several studies illustrate this divergence between patient and MHP.Reference Mestdagh and Hansen36 These paternalistic practices of care remain prevalent in Indian healthcare settings.Reference Ghooi and Deshpande37

Balancing custom with necessity

Perhaps the most evident and controversial dilemma in the THQ cultural adaptation process is finding a balance between asking the necessary questions and remaining sensitive to the customs of the culture. From the results, both user-survivors, and in particular MHPs, were resistant to the inclusion of rape in the trauma inventory because they felt it was too intrusive and emotionally arousing. Historically, the subject of rape has been a largely taboo topic in Indian society. At an estimated 8.5%, the prevalence of rape in India is considered relatively low compared with other countries; however, with only 1% of victims of sexual violence reporting their crimes, this is a gross underestimation of the reality.Reference Raj and McDougal38 Rape and other forms of sexual violence against women remain a taboo topic because not only does it result in physical harm of the victim, but it also disgraces and tarnishes the victim's psyche with devastating effect.Reference Sharma, Pardasani and Nandram39 With family members reported to be the most common perpetrators of sexual violence against women,Reference Chandra, Satyanarayana and Carey40 the social implications and associated stigma of reporting such cases are even higher. In light of the current increased visibility of the issue, and dramatic upsurge in cases of sexual violence against women being reported, we as researchers are faced with the dilemma of either providing a means to shed light on this highly relevant issue, or comply with social customs and further fuel the stigma and lack of awareness by discounting the problem.

Study limitations

Some study limitations must be noted. Our exclusion criteria limit our findings to the perspectives of user-survivors who were deemed cognitively abled and minimally symptomatic for participation in the focus group discussions. As the male user-survivors we attempted to recruit for this study were too symptomatic to participate, the feedback on the THQ was limited to the perspectives of female user-survivors of the target population. We suspect that although the items within the THQMV cover a range of PTEs that are relevant to both male and female user-survivors, differences in gender norms may dictate how comfortable some male respondents may feel in disclosing the occurrence of specific events.

Further research

We recommend further research to contribute to the development of trauma inventories for use in populations of homeless people with SMI. Although the focus group discussions with user-survivors have illustrated their capability of taking the inventory, the consistency of their responses over time or with different raters has yet to be determined. Further research to test the psychometric properties, specifically test–retest and interrater reliability of the adapted THQ, is required. Further piloting with male user-survivors would be necessary to determine any gender-related differences in perspectives on the usability and acceptability of the THQMV. Additionally, to understand potential differences in item response as a result of latent attributes such as gender, we recommend applying item response theory for further analysis.Reference Zanon, Hutz, Yoo and Hambleton41 With the addition of 21 new items to the inventory, a closer examination of its feasibility in practice is necessary to minimise respondent fatigue. Finally, further piloting the THQMV on patients with varying cognitive ability and symptom levels is required to investigate the true extent of the THQMV's utility in patients with SMI. This would allow us to understand the full spectrum of patients capable of undergoing a trauma inventory, and at what stage in their recovery it would be most feasible for administration of the tool.

Study implications and contribution

This study adds to the understanding of trauma as a valid construct in Indian populations, using qualitative means. At the same time, it reiterates Herdman et al's universalist approach to cross-cultural psychology.Reference Herdman, Fox-Rushby and Badia20 Although there are basic assumptions of what constitutes trauma that are recognised worldwide, culture significantly affects what types of events are considered traumatic, the severity of the impact and how it is addressed. We therefore recommend future studies use a universalist approach when validating screening tools for trauma. Although we expect that the applicability of the THQMV expands beyond homeless populations with SMI in Tamil Nadu, and is similarly relevant to other parts of the South Asia region, we recommend pre-explorative investigation of the needs and experiences of any target population, to ensure relevance and acceptability.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.952

Data availability

Anonymised data are available from the corresponding author, A.R.G., upon reasonable request, following formalised agreements made between the authors and interested parties.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincerest gratitude to Professor Pim Scholte and the care providers at The Banyan for their unwavering support throughout the research process. Above all else, the authors would like to thank the participants of the study, in particular the user-survivors, for their bravery and motivation to share their experiences and contribute to the success of this study.

Author contributions

A.R.G. drafted the work. A.R.G., S.V. and D.v.d.B. contributed to the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and critical revision of the work. R.M.H.P. and L.N. contributed to the analysis, interpretation and critical revision of the work. All authors gave their final approval of this version of the work to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure that all questions relating to accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved, as stipulated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.