31 results

African Worldmaking on a Global Stage - The Ideological Scramble for Africa: How the Pursuit of Anticolonial Modernity Shaped a Postcolonial Order, 1945–1966 Frank Gerits. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023. Pp. xi + 304. $67.95, hardcover (ISBN: 9781501767913).

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of African History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2025, pp. 1-2

-

- Article

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Mulk Raj Anand

- from Part II - 1900–1945

-

-

- Book:

- The British Novel of Ideas

- Published online:

- 05 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024, pp 192-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

27 - Colonial Legacies

- from Part V - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Understanding Colonial Nigeria

- Published online:

- 21 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 573-592

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Colonial African: Godwin Mbikusita-Lewanika and His Struggle For and Against Zambian Nationalism

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of African History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 November 2024, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The India League and the Condition of India: Agnotological Imperialism, Colonial State Violence and the Making of Anticolonial Knowledge 1930–4

-

- Journal:

- Transactions of the Royal Historical Society / Volume 2 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 October 2024, pp. 207-232

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Sikh Martyr Imaginaries during World War I

-

- Book:

- Constructing Religious Martyrdom

- Published online:

- 07 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024, pp 218-271

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Imperialism and the Queer Harlem Renaissance

- from Queer Literary Movements

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Queer American Literature

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 225-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - Malaria Literature

- from Part III - Applications: Politics

-

-

- Book:

- Literature and Medicine

- Published online:

- 17 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 263-280

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Colonial Subjects and the Struggle for Self-Determination, 1880–1918

- from Part ii - Paradigm Shifts and Turning Points in the Era of Globalization, 1500 to the Present

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Nationhood and Nationalism

- Published online:

- 27 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 329-349

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - From Wife to Comrade: Agnes Smedley and the Intimacies of Anticolonial Solidarity

- from Part II - Solidarities and Their Discontents

-

-

- Book:

- The Anticolonial Transnational

- Published online:

- 10 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2023, pp 111-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Cheikh Anta Diop’s Recovery of Egypt: African History as Anticolonial Practice

- from Part II - Solidarities and Their Discontents

-

-

- Book:

- The Anticolonial Transnational

- Published online:

- 10 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2023, pp 135-161

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - The Right to Petition in the Anticolonial Struggle at the United Nations

- from Part II - Solidarities and Their Discontents

-

-

- Book:

- The Anticolonial Transnational

- Published online:

- 10 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2023, pp 162-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Indoamerica against Empire: Radical Transnational Politics in Mexico City, 1925–1929

- from Part I - The Many Anticolonial Transnationals

-

-

- Book:

- The Anticolonial Transnational

- Published online:

- 10 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2023, pp 64-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

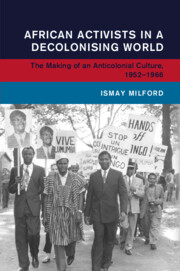

African Activists in a Decolonising World

- The Making of an Anticolonial Culture, 1952–1966

-

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023

5 - Mabo, Mob, and the Novel

- from Part I - Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Australian Novel

- Published online:

- 03 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 March 2023, pp 83-95

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Presencing

- from Part I - Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Australian Novel

- Published online:

- 03 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 March 2023, pp 25-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - David Galula in Algeria

-

- Book:

- The Counterinsurgent Imagination

- Published online:

- 18 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 January 2023, pp 156-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Rome, 1955–1957

- from Part I - Geographical, Institutional, and Interpersonal Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- Ralph Ellison in Context

- Published online:

- 14 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 02 December 2021, pp 81-90

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Parallel lives or interconnected histories? Anagarika Dharmapala and Muhammad Barkatullah's ‘world religioning’ in Japan

-

- Journal:

- Modern Asian Studies / Volume 56 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 November 2021, pp. 1329-1352

- Print publication:

- July 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

Introduction: Surrealism’s Critical Legacy

-

-

- Book:

- Surrealism

- Published online:

- 23 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 12 August 2021, pp 1-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation