Refine search

Actions for selected content:

116 results

Contentious Rituals and Intergroup Relations: Parading in Northern Ireland

-

- Journal:

- British Journal of Political Science / Volume 55 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 October 2025, e135

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Justice Concessions in Northern Ireland

-

- Book:

- Escaping Justice

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025, pp 127-169

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Escaping Justice

- Impunity for State Crimes in the Age of Accountability

-

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - The Land of Many Laws

- from Part III - Exits

-

-

- Book:

- Colonialism and the EU Legal Order

- Published online:

- 14 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025, pp 314-342

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Parliamentary Activism? Northern Irish Civil Rights and the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster

-

- Journal:

- Transactions of the Royal Historical Society / Volume 3 / December 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 August 2025, pp. 277-299

- Print publication:

- December 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 21 - Seamus Deane

- from Part III - Collaborators and Critics

-

-

- Book:

- Sean O'Casey in Context

- Published online:

- 23 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025, pp 222-232

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Polarisation and inequality: ‘peace’ in Northern Ireland

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Social Policy , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 March 2025, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Northern Ireland Childcare Strategy: A Work in Progress?

-

- Journal:

- Social Policy and Society , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 January 2025, pp. 1-14

-

- Article

- Export citation

Remembering Bloody Sunday 50 years on: A textual analysis of Bloody Sunday anniversary coverage

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Memory, Mind & Media / Volume 3 / 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 November 2024, e25

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - English in Ireland

- from Part I - English

-

-

- Book:

- Language in Britain and Ireland

- Published online:

- 17 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2024, pp 178-207

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Parting the Unions

-

-

- Book:

- The Conservative Effect, 2010–2024

- Published online:

- 24 July 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024, pp 236-283

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Ireland

- from Part I - Zones of Influence

-

-

- Book:

- Europe in British Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024, pp 70-84

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

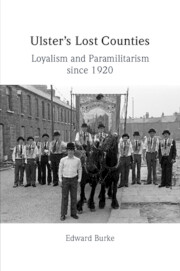

Chapter 1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Ulster's Lost Counties

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 1-30

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - The Last Ditch

-

- Book:

- Ulster's Lost Counties

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 185-237

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Ulster's Lost Counties

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 293-303

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - A Suspect Population

-

- Book:

- Ulster's Lost Counties

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 238-292

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Ulster's Lost Counties

- Loyalism and Paramilitarism since 1920

-

- Published online:

- 18 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024

Law and scale: lessons from Northern Ireland and Brexit

-

- Journal:

- Legal Studies / Volume 44 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 April 2024, pp. 201-220

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

10 - The European Union and the Wider Europe

-

- Book:

- European Union Law

- Published online:

- 19 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2024, pp 383-439

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Axes to Axes: the Chronology, Distribution and Composition of Recent Bronze Age Hoards from Britain and Northern Ireland

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 89 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2023, pp. 179-205

- Print publication:

- December 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation