Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Note to the Reader

- Introduction

- Part 1 The Present

- Part 2 The History

- Appendix 1 Kecak dan Wisata Budaya di Bali (Indonesian Summary)

- Appendix 2 Kecak Groups of Bali in 2000–2001 (Badung and Gianyar)

- Appendix 3 Facsimile of a Letter from Walter Spies to Leo Spies, 1932

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 October 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Note to the Reader

- Introduction

- Part 1 The Present

- Part 2 The History

- Appendix 1 Kecak dan Wisata Budaya di Bali (Indonesian Summary)

- Appendix 2 Kecak Groups of Bali in 2000–2001 (Badung and Gianyar)

- Appendix 3 Facsimile of a Letter from Walter Spies to Leo Spies, 1932

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

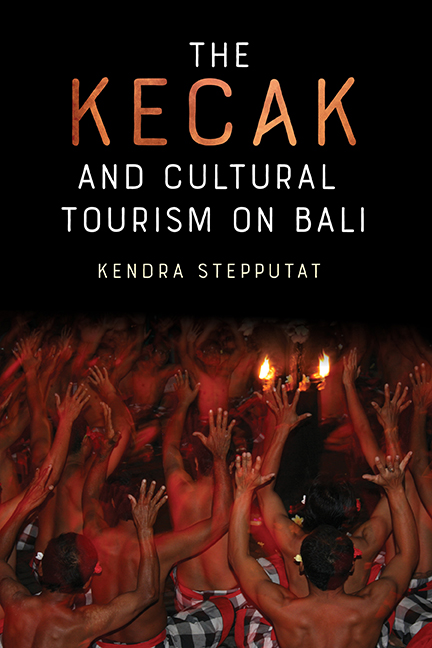

In the early evening hours of another hot and humid day on Bali, I enter the outer temple courtyard in the twilight and find a seat on one of the plastic garden chairs arranged on three sides of an open space. The only illumination is from a candelabra-like lamp with several coconut oil flames in the center of the stage, casting a warm, unstable light on the scene. The audience murmurs, readies their cameras, tries to read a leaflet in the dim light, puts on mosquito spray.

Then, the first sounds are heard—“caaaak” followed by “cak cak cak …”— explosive, short calls by a large group of men, structured, complex. The performers are not yet visible, but their voices come from behind the splitgate temple entrance. Once the rhythms become steady, the men finally appear through the central temple gates, one after the other, until maybe one hundred Balinese men of all ages have made their way onto the stage. They hold their arms and hands lifted high above their heads and shake them rapidly while they continue their fast, interlocking “cak” calls. The men form several concentric circles around the central lamp and sit down cross-legged. The central illumination casts seemingly more shadows than light onto the dancers’ faces and bare torsos, giving the scene a mystical atmosphere. After a short break in which the dancers adjust their seating positions, the “cak” calls start again with great intensity, loud and fast. Suddenly, the dancers lift their arms up into the air simultaneously, their hands shaking, the rapid movements enhanced by the reflections of the coconut oil flames—the kecak has begun.

When I first witnessed such a scene, I was overwhelmed by the visual and acoustic impact the kecak had on me. It was unlike anything I had seen before and left me dazzled. I wished to understand the musical structures, to learn more about the story, and to be able to appreciate the dance and theatrical parts beyond the strange amazement of this first encounter. At the site, I did not notice any of the other tourists and ignored their flashlights. I knew nothing about the multifaceted history of this amazing dramatic dance performance. Upon my return home to Germany, I realized that Bali had gotten into my system and that I wanted to go back and explore more.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Kecak and Cultural Tourism on Bali , pp. 1 - 10Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021