1. Reasons for Presenting Research

There are several pros and cons to evaluate when deciding whether to submit your research to a conference. There is value in sharing your science with others at the conference, such as professors, students, clinicians, teachers, and other professionals who might be able to use your work to advance their own work. As a personal gain, your audience may provide feedback, which may be invaluable to you in your professional development. Presenting research at conferences also allows for the opportunity to meet potential future advisors, employers, collaborators, or colleagues. Conferences are ideal settings for networking and, in fact, many conferences have forums organized for this exact purpose (e.g., job openings listed on a bulletin board and networking luncheons). The downsides to submitting your work to a conference include the time commitment of writing and constructing the presentation, the potential for rejection from the reviewers, the anxiety inherent in formal presentations, and the potential time and expenses of traveling to the meeting. Although we do believe that the benefits of presenting at conferences outweigh the costs, you should carefully consider your own list of pros and cons before embarking on this experience.

2. Presentation Venues

There are many different outlets for presenting research findings, ranging from departmental colloquia to international conferences. The decision of submitting a proposal to one conference over another should be guided by both practical and professional reasoning. In selecting a convention, you might consider the following questions: Is this the audience to whom I wish to disseminate my findings? Are there other professionals that I would like to meet attending this conference? Are the other presentations of interest to me? Are the philosophies of the association consistent with my perspectives and training needs? Can I afford to travel to this location? Will my institution provide funding for the cost of this conference? Will my presentation be ready in time for the conference? Am I interested in visiting the city that is hosting the conference? Do the dates of the conference interfere with personal or professional obligations? Will this conference provide the opportunity to network with colleagues and friends? Is continuing education credit offered? Associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, many meetings are virtual, which provides a lower-cost option, but networking is more challenging and the options of linking a vacation to the conference is no longer an option. Fortunately, there are a range of options and you should be able to find a venue that satisfies most of your professional presenting needs.

3. Types of Presentations

After selecting a conference, you must decide on the type of presentation. In general, presentation categories are similar across venues and include poster and oral presentations (e.g., papers, symposia, panel discussions) and workshops. In general, poster presentations are optimal for disseminating preliminary or pilot findings, whereas well-established findings, cutting-edge research, and conceptual/theoretical issues often are reserved for oral presentations and workshops. A call for abstracts or proposals is often distributed by the institution hosting the conference and announces particular topics of interest for presentations. If you are unsure about whether your research is best suited for a poster or oral presentation or workshop, refer to the call for abstracts or proposals and consult with more experienced colleagues. Keynote and invited addresses are other types of conference proceedings typically delivered by esteemed professionals or experts in the field. It is important to note that not all conferences use the same terminology, especially when comparing conferences across countries. For example, a “workshop” at one conference might be a full-day interactive training session and at another conference it might indicate a briefer oral presentation. The following sections are organized in accord with common formats found in many conferences.

The most common types of conference presentations, poster presentations, symposia, panel discussions, and workshops, deserve further discussion. Typically, these scientific presentations follow a consistent format, which is similar to the layout of a research manuscript. For example, first you might introduce the topic, highlight related prior work, outline the purpose and hypotheses of the study, review the methodology, and, lastly, present and discuss salient results and implications (see Reference Drotar and DrotarDrotar, 2000).

3.1 Poster Presentations

Poster presentations are the most common medium through which researchers disseminate findings. In this format, researchers summarize their primary aims, results, and conclusions in an easily digestible manner on a poster board. Poster sessions vary in duration, often ranging from 1 to 2 hours. Authors typically are present with their posters for the duration of the session to discuss their work with interested colleagues. Poster presentations are relatively less formal and more personal than other presentation formats, with the discussion of projects often assuming a conversational quality. That said, it is important to be prepared to answer challenging questions about the work. Typically, many posters within a particular theme (e.g., health psychology) are displayed in a large room so that audiences might walk around the room and talk one-to-one with the authors. Thus, poster sessions are particularly well-suited for facilitating networking and meeting with researchers working in similar areas.

Pragmatically, conference reviewers accept more posters for presentations than symposia, panel discussion, and workshops, and thus, the acceptance criteria are typically more lenient. Relatedly, researchers might choose posters to present findings from small projects or preliminary or pilot results studies. Symposia, panel discussions, and workshops allow for the formal presentation of more ground-breaking findings or of multiple studies. Poster presentations are an opportune time for students to become familiarized with disseminating findings and mingling with other researchers in the field.

3.2 Research Symposia

Symposia involve the aggregation of several individuals who present on a common topic. Depending on time constraints, 4–6 papers typically are featured, each lasting roughly 20 minutes, and often representing different viewpoints or facets of a broader topic. For example, a symposium on the etiology of anxiety disorders might be comprised of four separate papers representing the role of familial influences, biological risk factors, peer relationships, and emotional conditioning on the development of maladaptive anxiety. As a presenter, you might discuss one project or the findings from a few studies. Like a master of ceremonies, the symposia Chair typically organizes the entire symposia by selecting presenters, guiding the topics and style of presentation, and introducing the topic and presenters at the beginning of the symposium. In addition to these duties, the Chair often will present a body of work or a few studies at the beginning of the symposium. In addition to the Chair and presenters, a Discussant can be part of a symposium. The Discussant concludes the symposium by summarizing key findings from each paper, integrating the studies, and making more broad-based conclusions and directions for future research. Although a Discussant is privy to the presenters’ papers prior to the symposium in order to prepare the summary comments, he or she will often take notes during the presenters’ talks to augment any prepared commentary. Presenters are often researchers of varying levels of experience, while Chairs and Discussants are usually senior investigators. The formal presentation is often followed by a period for audience inquiry and discussion.

3.3 Panel Discussions

Panel discussions are similar to research symposia in that several professionals come together to discuss a common topic. Panel discussions, however, generally tend to be less formal and structured and more interactive and animated than symposia. For example, Discussants can address each other and interject comments throughout the discussion. Similar to symposia, these presentations involve the discussion of one or more important topics in the field by informed Discussants. As with symposia presentations, the Chair typically organizes these semi-formal discussions by contacting potential speakers and communicating the discussion topic and their respective roles.

3.4 Workshops

Conference workshops typically are often longer (e.g., lasting at least three hours) and provide more in-depth, specialized training than symposia and panel discussions. It is not uncommon for workshop presenters to adopt a format similar to a structured seminar, in which mini-curricula are followed. Due to the length and specialized training involved, most workshop presenters enhance their presentations by incorporating interactive (e.g., role-plays) and multimedia (e.g., video clips) components. Workshops often are organized such that the information is geared for beginner, intermediate, or advanced professionals. Often conferences are organized such that participation in workshops must be reserved in advance and there might be additional fees associated with attendance. The cost should be balanced with the opportunity of obtaining unique training in a specialized area. These are most often presented by seasoned professionals; however, more junior presenters with specialized skills/knowledge might conduct a workshop.

4. The Application Process

After selecting a venue and deciding on a presentation type, the next step is to submit an application to the conference you wish to attend. The application process typically involves submitting a brief abstract (e.g., 200–300 words) describing the primary aims, methods, results, and conclusions of your study. For symposia and other oral presentations, the selection committee might request an outline of your talk, curriculum vitae from all presenters, and a time schedule or presentation agenda. Some conferences might also request information regarding the educational objectives and goals of your presentation. One essential rule is to closely adhere to the directions for submissions to the conference. For example, if there is a word limit for a poster abstract submission, make sure that you do not exceed the number of words. Whereas some reviewers might not notice or mind, others might view it is as unprofessional and possibly disrespectful and an easy decision rule to use to reject a submission.

Although the application process itself is straightforward, there are differences in opinion regarding whether and when it is advisable to submit your research. A commonly asked question is whether a poster or paper can be presented twice. Many would agree that it is acceptable to present the same data twice if the conferences draw different audiences (e.g., regional versus national conferences). Another issue to consider is when, or at what stage, a project should be submitted for presentation. Submitting research prior to analyzing your data can be risky. It would be unfortunate, for example, to submit prematurely, such as during the data collection phase, only to find that your results are not ready in time for the conference. Although some might be willing to take this risk, remember that it is worse to present low-quality work than not to present at all.

5. Preparing and Conducting Presentations

5.1 Choosing an Appropriate Outfit

Dress codes for conference proceedings typically are not formally stated; however, data suggest that perceptions of graduate student professionalism and competence are influenced by dress (e.g., Reference Gorham, Cohen and MorrisGorham et al., 1999). Although the appropriateness of certain attire is likely to vary, a good rule of thumb is to err on the side of professionalism. You also might consider the dress of your audience, and dress in an equivalent or more formal fashion. Although there will be people at conferences wearing unique styles of dress, students and professionals still early in their careers are best advised to dress professionally. It can be helpful to ask people who have already attended the conference what would be appropriate to wear. In addition to selecting your outfit, there are several preparatory steps you can take to help ensure a successful presentation.

5.2 Preparing for Poster Presentations

5.2.1 The Basics

The first step in preparing a poster is to be cognizant of the specific requirements put forth by the selected venue. For example, very specific guidelines often are provided, detailing the amount of board space available for each presenter (typically a 4-foot by 6-foot standing board is available). To ensure the poster will fit within the allotted space, it may be helpful to physically lay it out prior to the conference. This also may help to reduce future distress, given that back-to-back poster sessions are the norm; knowing how to arrange the poster in advance obviates the need to do so hurriedly in the few minutes between sessions. If you are using PowerPoint to design your poster, you can adjust the size of your layout to match the conference requirements.

5.2.2 Tips For Poster Construction

The overriding goal for poster presentations is to summarize your study using an easily digestible, reader-friendly format (Reference GrechGrech, 2018b). As you will discover from viewing other posters, there are many different styles to do this. If you have the resources, professional printers can create large glossy posters that are well received. However, cutting large construction paper to use as a mat for laser-printed poster pages can also appear quite professional. Some companies will even print the poster on a fabric material, so it can be folded up and stored easily in a suitcase for travel to and from the conference. Regardless of the framing, it is advisable to use consistent formatting (e.g., same style and font size throughout the poster), large font sizes (e.g., at least 20-point font for text and 40-point font for headings), and alignment of graphics and text (Reference Zerwic, Grandfield, Kavanaugh, Berger, Graham and MershonZerwic et al., 2010). Another suggestion for enhancing readability and visual appeal is to use bullets, figures, and tables to illustrate important findings. Generally speaking, brief phrases (as opposed to wordy paragraphs) should be used to summarize pertinent points. It has been suggested to limit horizontal lines to 10 or fewer words and avoid using more than four colors (Reference Zerwic, Grandfield, Kavanaugh, Berger, Graham and MershonZerwic et al., 2010). In short, it is important to keep your presentation succinct and avoid overcrowding on pages. Although there are a variety of fonts available and poster boards come in all colors imaginable, it is best to keep the poster professional. In other words, Courier, Arial, or Times New Roman are probably the best fonts to use because they are easy to read and they will not distract or detract from the central message of the poster (i.e., your research). In addition, dark font (e.g., blue, black) on a light background (e.g., yellow, white) is easier to read in brightly lit rooms, which is the norm for poster sessions. Be mindful of appropriately acknowledging any funding agencies or other organizations (e.g., universities) on the poster or in the oral presentation slides. Recently, the format of posters has shifted. The “better poster” format (https://youtu.be/1RwJbhkCA58) includes the main research finding in large text in the center of the poster with extra details and figures on the sides (Figure 12.1). This allows conference attendees to quickly assess whether the research is of interest to them and if they would like more detailed information.

Figure 12.1 Poster formats.

5.2.3 What To Bring

When preparing for a poster presentation, consider which materials might be either necessary or potentially useful to bring. For instance, it might be wise to bring tacks (Reference GrechGrech, 2018b). It also is advisable to create handouts summarizing the primary aims and findings and to distribute these to interested colleagues. The number of copies one provides often depends on the size of the conference and the number of individuals attending a particular poster session. We have found that for larger conferences, 20 handouts are a good minimum. In general, handouts are in high demand and supplies are quickly depleted, in which case, you should be equipped with a notepad to obtain the names and addresses of individuals interested in receiving the handout via mail or e-mail. With the “better poster” format, researchers often include a QR code on their poster. The QR code can link them to a copy of the poster, contact information of the researchers, or other relevant electronic documents.

5.2.4 Critically Evaluate Other Posters

We also recommend critically evaluating other posters at conferences and posters previously used by colleagues. You will notice great variability in poster style and formatting, with some researchers using glossy posters with colored photographs and others using plain white paper and black text. Make mental notes regarding the effective and ineffective presentation of information. What attracted you to certain posters? Which colors stood out and were the most readable? Such informal evaluations likely will be invaluable when making decisions on aspects such as poster formatting, colors, font, and style.

5.2.5 Prepare Your Presentation

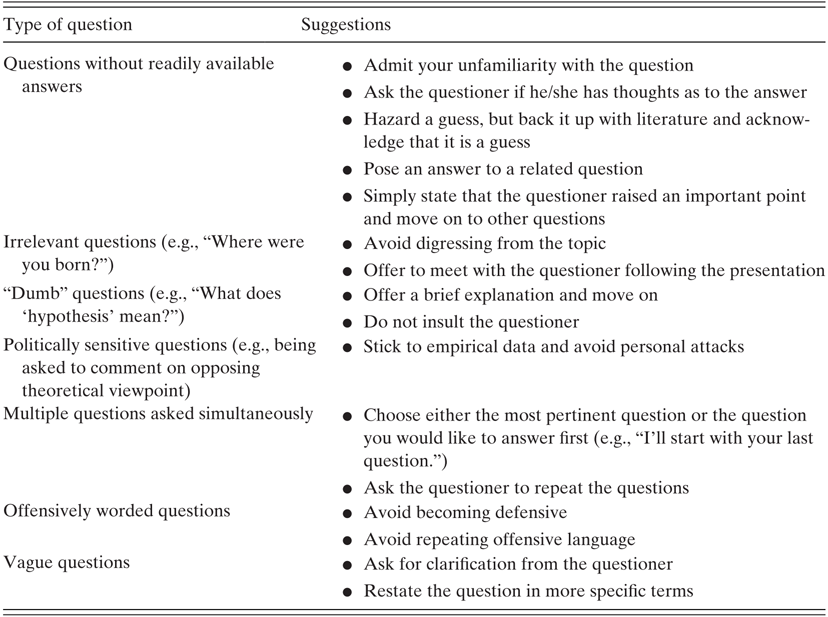

Poster session attendees will often approach your poster and ask you to summarize your study, so it is wise to prepare a brief overview of your study (e.g., 2 minutes). In addition, practice describing any figures or graphs displayed on your poster. Finally, attendees will often ask questions about your study (e.g., “What are the clinical implications?”, “What are some limitations to your study?”, “What do you recommend for future studies?”), so it may be helpful to have colleagues review your poster and ask questions. Table 12.1 provides some suggestions as to how to handle difficult questions.

Table 12.1 Handling difficult questions

| Type of question | Suggestions | |

|---|---|---|

| Questions without readily available answers |

| |

| Irrelevant questions (e.g., “Where were you born?”) |

| |

| “Dumb” questions (e.g., “What does ‘hypothesis’ mean?”) |

| |

| Politically sensitive questions (e.g., being asked to comment on opposing theoretical viewpoint) |

| |

| Multiple questions asked simultaneously |

| |

| Offensively worded questions |

| |

| Vague questions |

| |

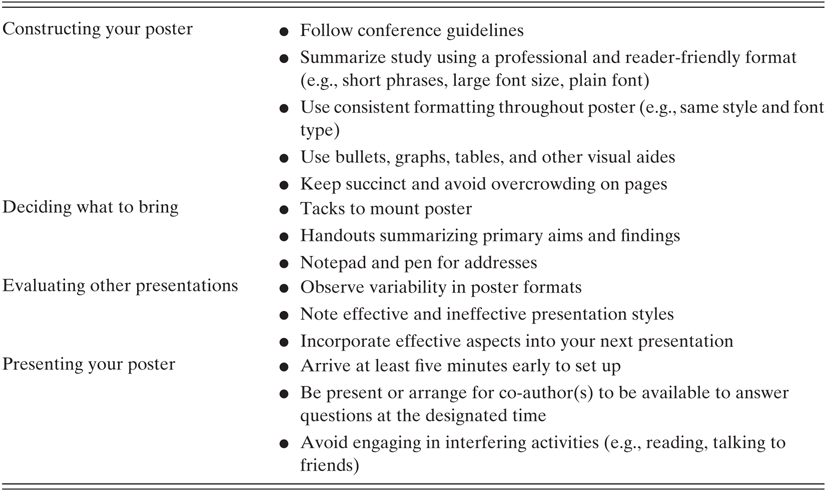

5.3 Conducting Poster Presentations

In general, presenting a poster is straightforward – tack the poster to the board at the beginning of the session, stand next to the poster and discuss the details of the project with interested viewers, and remove the poster at the end of the session. However, we have found that a surprisingly high number of presenters do not adequately fulfill these tasks. Arriving to the poster session at least five minutes early will allow you to find your allocated space, unpack your poster, and decide where to mount it on the board. When posters consist of multiple frames, it might be easiest to lie out the boards on the floor prior to beginning to tack it up on the board.

During the poster session, remember this fundamental rule – be present. It is permissible to browse other posters in the same session; however, always arrange for a co-author or another colleague knowledgeable about the study to man the poster. Another guideline is to be available to answer questions and discuss the project with interested parties. In other words, refrain from reading, chatting with friends, or engaging in other activities that interfere with being available to discuss the study. At the conclusion of the poster session, it is important to quickly remove your poster so subsequent presenters have ample time to set up their posters. Suggestions for preparing and presenting posters are summarized in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Suggestions for poster presentations

| Constructing your poster |

|

| Deciding what to bring |

|

| Evaluating other presentations |

|

| Presenting your poster |

|

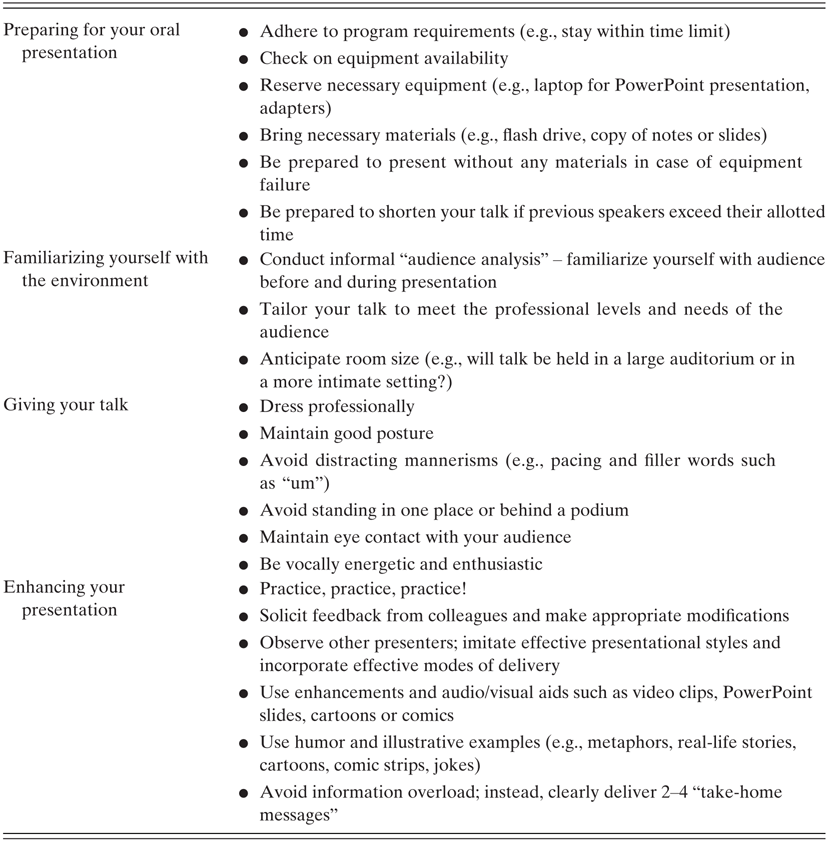

5.4 Preparing for Oral Presentations

5.4.1 The Basics

Similar to poster sessions, it is important to be familiar with and adhere to program requirements when preparing for oral presentations. For symposia, this might include sending an outline of your talk to the Chair and Discussant several weeks in advance and staying within a specified time limit when giving your talk. Although the Chair often will ensure that the talks adhere to the theme and do not excessively overlap, the presenter also can do this via active communication with the Chair, Discussant, and other presenters.

5.4.2 What To Bring

As with poster presentations, it is useful to anticipate and remember to bring necessary and potentially useful materials. For instance, individuals using PowerPoint should bring their slides in paper form in case of equipment failure. Equipment, such as microphones, often are available upon request; it is the presenter’s responsibility, however, to reserve equipment in advance.

5.4.3 Critically Evaluate Other Presenters

By carefully observing other presenters, you might learn valuable skills of how to enhance your presentations. Examine the format of the presentation, the level of detail provided, and the types and quality of audiovisual stimuli. Also try to note the vocal quality (e.g., intonation, pitch, pace, use of filler terms such as “um”), facial characteristics (e.g., smiling, eye contact with audience members), body movements (e.g., pacing, hand gestures), and other subtle aspects that can help or hinder presentations.

5.4.4 Practice, Practice, Practice

In terms of presentation delivery, repeated practice is essential for effective preparation (see Reference Williams, Pequegnat and StoverWilliams, 1995). For many people, students and seasoned professionals alike, public speaking can elicit significant levels of distress. Given extensive data supporting the beneficial effects of exposure to feared stimuli (see Reference WolpeWolpe, 1977), repeated rehearsal is bound to produce positive outcomes, including increased comfort, increased familiarity with content, and decreased levels of anxiety. Additionally, practicing will help presenters hone their presentation skills and develop a more effective presentational style. We recommend practicing in front of an “audience” and soliciting feedback regarding both content and presentational style. Solicit feedback on every aspect of your presentation from the way you stand to the content of your talk. It might be helpful to rehearse in front of informed individuals (e.g., mentors, graduate students, research groups) who ask relevant and challenging questions and subsequently provide constructive feedback (Reference GrechGrech, 2018a; Reference Wellstead, Whitehurst, Gundogan and AghaWellstead et al., 2017). Based on this feedback, determine which suggestions should be incorporated and modify your presentation accordingly. As a general rule, practice and hone your presentation to the point that you are prepared to present without any crutches (e.g., notes, overheads, slides).

5.4.5 Be Familiar and Anticipate

As much as possible, try to familiarize yourself with the audience both before and during the actual presentation (Reference Baum and BoughtonBaum & Boughton, 2016; Reference RegulaRegula, 2020). By having background information, you can better tailor your talk to meet the professional levels and needs of those in attendance. It may be particularly helpful to have some knowledge regarding the educational background and general attitudes and interests of the audience (e.g., is the audience comprised of laymen and/or professionals in the field? What are the listeners’ general attitudes toward the topic and towards you as the speaker? Is the audience more interested with practical applications or with design and scientific rigor?). Are you critiquing previous work from authors that may be in the audience? By conducting an informal “audience analysis,” you will be more equipped to adapt your talk to meet the particular needs and interests of the audience. It is important to have a clear message that you want the audience to take with them after the presentation (Reference RegulaRegula, 2020). Most conference-goers will be seeing many presentations during the conference, so having a clear take-home message can make it easier for the audience to remember the key points.

Similarly, it might be helpful to have some knowledge about key logistical issues, such as room size and availability of equipment (Reference Baum and BoughtonBaum & Boughton, 2016). For example, will the presentation take place in a large, auditorium-like room or in a more intimate setting with the chairs arranged in a semi-circle? If the former, will a microphone be available? Is there a podium at the front of the room that might influence where you will stand? Given the dimensions of the room, where should the slide projector be positioned? Although it may be impossible to answers all such questions, it is a good idea to have a general sense of where the presentation will take place and who will be attending. It may also help to rearrange the seating, so that latecomers do not pose as a distraction (Reference Baum and BoughtonBaum & Boughton, 2016). Suggestions for preparing and conducting oral presentations are summarized in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3 Oral presentations

| Preparing for your oral presentation |

|

| Familiarizing yourself with the environment |

|

| Giving your talk |

|

| Enhancing your presentation |

|

If the conference is virtual, it is critical to become familiar with the software or online platform well in advance of a synchronous event. For example, practicing with the camera and microphone and watching recordings of yourself will allow you to fine-tune the presentation and audio quality. Whether synchronous or asynchronous, there are a number of tips for optimizing video presentations, including how to position the camera, how to light the presenter, behaviors to include or avoid, and what to consider in terms of the background. Given the variability and subjectivity related to video presentation suggestions, we encourage the readers to research this extensive topic to personalize and optimize their virtual presentations.

5.5 Conducting Oral Presentations

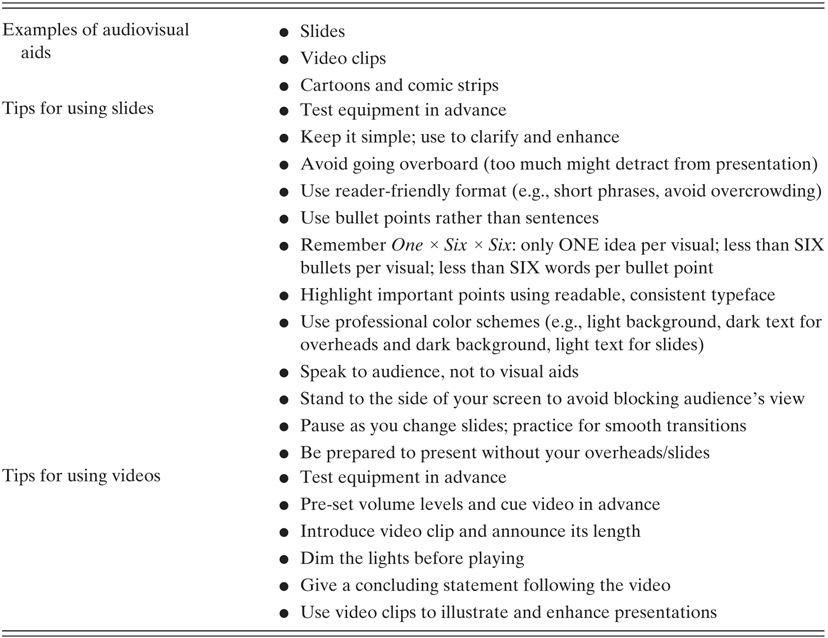

5.5.1 Using Audiovisual Enhancements

One strategy for enhancing oral presentations is to use audio/visual stimuli, such as slides or props (e.g., Reference GrechGrech, 2019; Reference HoffHoff, 1988; Reference WilderWilder, 1994; see Table 12.4). When using visual enhancements, keep it simple, and clearly highlight important points using readable and consistent typeface (Reference Blome, Sondermann and AugustinBlome et al., 2017; Reference GrechGrech, 2018a). Information should be easily assimilated and reader-friendly, which generally means limiting text to a few phrases rather than complete sentences or paragraphs and using sufficiently large font sizes (e.g., 36- to 48-point font for titles and 24- to 36-point font for text). In addition, it is a good idea to keep titles to one line and bullets to no more than two lines of information. Additionally, color schemes should be relatively subdued and “professional” in appearance. For slide presentations, a dark background and light text might be easier to read. Utilize fonts without serifs (e.g., Arial) as opposed to fonts with serifs (e.g., Times New Roman; Reference Lefor and MaenoLefor & Maeno, 2016). Some conferences prefer a particular slide size, so it can be important to check with their requirements before designing the presentation. Additionally, depending on the room set up, it can be hard for the audience to see the bottom of slides, so it can be helpful to avoid placing text near the bottom of the slide. See Figure 12.2 for an example of a poor and good slide for an oral presentation.

Table 12.4 Using audiovisual enhancements

| Examples of audiovisual aids |

|

| Tips for using slides |

|

| Tips for using videos |

|

Figure 12.2 Sample poor and good slides for an oral presentation.

Using audiovisual aids, such as video clips, also can contribute substantially to the overall quality and liveliness of a presentation. When incorporating video clips, pre-set volume levels and cue up the video in advance. We also recommend announcing the length of the video, dimming lights, and giving a concluding statement following the video.

Multimedia equipment and audiovisual aids have the potential to liven up even the most uninspiring presentations; however, caution against becoming overly dependent on any medium. Rather, be fully prepared to deliver a high-quality presentation without the use of enhancements. It also might be wise to prepare a solid “back-up plan” in case your original mode of presentation must be abandoned due to equipment failure or some other unforeseen circumstance. Back-up overheads, for example, might rescue a presenter who learns of equipment failures minutes before presenting.

When using slides, it is important to avoid “going overboard” with information (Reference Blome, Sondermann and AugustinBlome et al., 2017; Reference RegulaRegula, 2020). Many of us will present research with which we are intimately familiar and invested. With projects that are particularly near and dear (e.g., theses and dissertations), it may be tempting to tell the audience as much as possible. It is not necessary, for example, to describe the intricacies of the data collection procedure and present every pre-planned and post-hoc analysis, along with a multitude of significant and non-significant F-values and coefficients. Such information overload might bore audience members, who are unlikely to care about or remember so many fine-grained details. Instead of committing this common presentation blunder, present key findings in a bulleted, easy-to-read format rather than sentences. To avoid overcrowding of slides and overheads, you might remember the One × Six × Six rule of thumb: only ONE idea per visual, less than SIX bullets per visual, and less than SIX words per bullet (Reference RegulaRegula, 2020; see Figure 12.2).

The length of your oral presentation will vary depending on time restrictions, but there are some general guidelines for how to structure your presentation. Reference Zerwic, Grandfield, Kavanaugh, Berger, Graham and MershonZerwic et al. (2010) proposed a possible structure for research presentations, which should include a title, acknowledgments, background, specific aims, methods, results, conclusions, and future directions sections. Zerwic et al. also recommended how many slides should be allocated to each section with your title, acknowledgments, background, specific aims, conclusions, and future directions sections each taking up one slide with the majority of your slides focusing on the methods and results sections.

In short, remember and hold fast to this basic dictum: Audio/visual aids should be used to clarify and enhance (Reference CohenCohen, 1990; Reference GrechGrech, 2018a; Reference WilderWilder, 1994). Aids that detract, confuse, or bore one’s audience should not be used (soliciting feedback from colleagues and peers will assist in this selection process; Reference RegulaRegula, 2020). Overly colorful and ornate visuals or excessive slide animation, for example, might detract and distract from the content of the presentation (Reference Lefor and MaenoLefor & Maeno, 2016). Likewise, visual aids containing superfluous text might encourage audience members to read your slides rather than attend to your presentation. Keeping visuals simple also might prevent another presentation faux pas: reading verbatim from slides.

5.5.2 Using Humor and Examples

The effective use of humor might help “break the ice,” putting you and your audience at ease. There are many ways in which humor can be incorporated into presentations, such as through the use of stories, rich examples, jokes, and cartoons or comic strips. As with other aids, humor should be used in moderation and primarily to enhance a presentation (Reference CollinsCollins, 2004). When using humor, it is important to be natural and brief and to use non-offensive humor related to the subject matter.

Another strategy for spicing up presentations is through the use of stories and examples to illustrate relevant and important points (Reference Bekker and ClarkBekker & Clark, 2018). This can be accomplished in many ways, such as by providing practical and real-life examples or by painting a mental picture for the audience using colorful language (e.g., metaphors, analogies). Metaphorical language, for instance, might facilitate learning (Reference SkinnerSkinner, 1953) and help audience members to remember pertinent information. Similarly, amusing stories and anecdotes can be used to engage the audience and decrease the “impersonal feel” of more formal presentations. Regardless of whether or how humor is used, remember to do what “works” and feels right. Trying too hard to be amusing may come across as contrived and stilted, thus producing the opposite of the intended effect.

5.5.3 Attending To Other Speakers

When presenting research in a group forum (e.g., symposia), it may be beneficial to attend to other speakers, particularly those presenting before you. Being familiar with the content of preceding talks will help to reduce the amount of overlap and repetition between presentations (although some overlap and repetition might be desirable). You might, for example, describe the similarities and differences across research projects and explain how the current topic and findings relate to earlier presentations. The audience probably will appreciate such integration efforts and have a better understanding of the general topic area.

5.5.4 Answering Questions

Question and answer sessions are commonplace at conferences and provide excellent opportunities for clarifying ambiguous points and interacting with the audience. When addressing inquiries, it is crucial to maintain a professional, non-defensive demeanor (Reference Wellstead, Whitehurst, Gundogan and AghaWellstead et al., 2017). Treat every question as legitimate and well-intentioned, even if it comes across as an objection or insult. As a general rule, in large auditoriums it is good to repeat the question so that everyone in the room hears it. If a question is unclear or extremely complicated, it may be wise to pause and organize your thoughts before answering. If necessary, request clarification or ask the questioner to repeat or rephrase the question. It also may be helpful to anticipate and prepare for high-probability questions (Reference WilderWilder, 1994).

There are several types of difficult questions that can be anticipated, and it is important to know how to handle these situations (Table 12.1). Also, we recommend preparing for a non-responsive audience. If audience members do not initiate questions, some tactics for preventing long, uncomfortable silences are to pose commonly asked questions, reference earlier comments, or take an informal survey (e.g., “Please raise your hand if you work clinically with this population.”). Even if many questions are generated and lead to stimulating discussions, it is important to adhere to predetermined time limits. End on time and with a strong concluding statement.

Above all, avoid becoming defensive and critical, particularly when answering challenging questions. Irrespective of question quality or questioner intent, avoid making patronizing remarks or answering in a way that makes the questioner feel foolish or incompetent. Try to avoid falling into an exclusive dialogue with one person, which might cause other members of the audience to feel excluded or bored. If possible, offer to meet with the questioner and address their questions and concerns at the end of the talk. Another suggestion is to avoid engaging in mini-lectures by showcasing accumulated knowledge and expertise in a particular area. Instead, only provide information that is directly relevant to the specific question posed by the audience (Reference WilderWilder, 1994).

6. Conclusion

There are great benefits to presenting research, both to the presenter and the audience. Before presenting, however, you should consider carefully a number of preliminary issues. For instance, you must decide whether your study is worthy of presentation, where to present it, and what type of presentation to conduct. Once these decisions are made, prepare by practicing your presentation, examining other presentations, and consulting with colleagues. Sufficient preparation should enhance the quality of your presentation and help decrease performance anxiety. We are confident that you will find that a well-executed presentation will prove to be a rewarding and valuable experience for you and your audience.