Sound, as a physical phenomenon, is measurable and quantifiable, and exists independent of culture in the form of vibrations. The human sensation of sound, however, is an entirely different matter. Once a vibrating sound wave is perceived by humans, it can become music or noise or go unheard altogether – an experiential phenomenon that depends on the culture, habitat, and environmental conditions which inform how one hears the physical world. As these conditions change over time, so too does the experience of interpreting sound. But sound leaves no trace, so in order to historicize it, we must rely on what people wrote about what they heard and what drew their interest and attention over time.

The eighteenth century ushered in profound changes to how people listened and what they listened to. The quest for universal values brought regional sonic diversity to the forefront of inquiries into issues of human diversity and national characteristics. Sound became one of many boundaries drawn between who was and who was not included in new definitions of national identity, and if we believe – with Homi Bhabha – that ‘the boundary becomes the place from which something begins its presencing’, we can say that sounds conceived of as boundaries brought new forms of cultural presence.1 Phenomena such as musical exoticism, the collecting of national airs, and aural tourism emerged from a cultural context that oscillated between universalism and particularism.2 Collecting national airs, a central topic of this chapter, brought local aural phenomena into the global world through print and/or performance. For example, in the eighteenth century Scottish songs made their way to the Continent through print, songs from India made their way to Britain, first through private correspondence and subsequently through printing; a few specimens of national songs from around the world were included in the tables in Rousseau’s Dictionnaire de musique and Jean-Benjamin de Laborde’s 1780 Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne dedicated its entire fourth book to ‘Chansons’, with special sections ranging from Gaelic songs to Chinese ones.3 Catherine Mayes states that ‘it was precisely during the decades around 1800 that the recognition and celebration of music as nation-defining flourished alongside detailed discussions of the essential characteristics of various national musics in contemporary writings. Yet the emerging importance of music to national identity at this time appears to be quite at odds with generic representations.’4 Her point, discussed also by Bellman and Locke in their studies on musical exoticism, is that representations of the Other’s music (in Mayes’s article the ‘Other’ is Eastern Europe) are not accurate in their choice of the musical material and language. These representations hint at something that audiences could experience as ‘exotic’, but they always ‘tame’ the music of the others, making it ‘harmless’ to Western European ears.5 However, one might wonder whether that does not hold true of any form of broad representation of the Other, especially when it needs to sell. The case of the publication of tunes in Scottish song collections, discussed in this chapter, reveals how this tampering with musical traditions was a practice common even within national borders.

In the words of Vicesimus Knox, the ballad in the eighteenth century was ‘rescued from the hands of the vulgar, to obtain a place in the collection of the man of taste. Verses which a few years past were thought worthy the attention of children only, are now admired for that artless simplicity which once obtained the name of coarsness and vulgarity.’6 What did this process of ‘rescuing’ imply and how did it transform the oral ballad tradition? This chapter examines how local historical soundscapes became a focal point in the collection of national airs as Britain invented national traditions and defined national culture in the century after the Act of Union of 1707.7 In particular, collectors found in local Scottish ballads certain ‘national properties’ of the unified kingdom. As Matthew Gelbart demonstrates, Scotland ‘lay at the heart of the first discussions in English of “national music”’,8 and it is to Scotland that we will turn most of our attention.

This chapter begins by surveying key discussions surrounding the invention of Britishness, such as Hume’s reflections on ‘national characters’ and the Scottish Enlightenment practice of conjectural history. These discourses provide a foundation for understanding the Scottish ballad revival and the birth of the concept of oral culture that are discussed in the second part of this chapter. I argue that many of the phenomena which have been treated separately in academic writing share common roots, and that tracing those roots reveals how the meaning of aural practices and experiences such as listening to ballads changed over time. As part of this process, once obscure records of local soundscapes found a new and powerful resonance in a nation inventing itself. The second part of the chapter will also address the problem of musical scores published in several ballad collections in light of questions pertaining to authenticity and tradition.

History, Judgement, and Taste

The study of the sense of hearing was part of a larger change in eighteenth-century episteme. At the end of the seventeenth century the foundations for a new way of understanding the relationship between the senses, the physical world, and human perception emerged. The discussions unleashed by the Molyneux problem (would a person born blind and accustomed to recognize objects like a sphere or a cube by touch recognize them only by sight if surgery gave this person the ability to see?) led many philosophers to investigate the way in which sensations and ideas are generated. The interplay between objects as they existed in the physical world and the sensory experiences that informed human perceptions of them also became a focal point of philosophical inquiry, as did the relationship between sound and hearing, which was investigated in philosophical treatises on aesthetics, the arts, music, and medicine. A typical crux in these discussions arose when the difference among tastes was mentioned. If humankind was supposed to share the same mental faculties and body senses, and hence the same universal features, how could the diversity of regional and national tastes be explained?9

In the first half of the eighteenth century, the notion of tabula rasa, discussed by John Locke in the second book of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), informed British answers to this question: individuals were endowed with the same mental faculties, and the mind, prior to experience, was comparable to a blank sheet, devoid of content. The diversity of human tastes and preferences therefore emerged from habits, experience, and associations. Just as climate acted upon the passions of nations, so too did the environment shape the tastes and desires of individuals. Tensions soon emerged between such explanations for the origins of individual taste and the need to define standards of national tastes.10 Towards the end of his Essay of the Standard of Taste (1760), Hume admits that: ‘Notwithstanding all our endeavours to fix a standard of taste, and reconcile the discordant apprehensions of men, there still remain two sources of variation. … The one is the different humours of particular men; the other, the particular manners and opinions of our age and country.’11 The manners of the country, and especially its form of government, are key for Hume’s argument that the development of culture and the arts requires specific political conditions. Only once a nation has formed a government of laws could the arts and sciences develop. In his essay The Sceptic (1742), Hume goes back to the problem of the multiplicity of tastes:

nature is more uniform in the sentiments of the mind than in most feelings of the body, and produces a nearer resemblance in the inward than in the outward part of human kind. There is something approaching to principles in mental taste; and critics can reason and dispute much more plausibly than cooks or perfumers. We may observe, however, that this uniformity among human kind, hinders not, but that there is a considerable diversity in the sentiments of beauty and worth, and that education, custom, prejudice, caprice, and humour frequently vary our taste of this kind. You will never convince a man, who is not accustomed to Italian music, and has not an ear to follow its intricacies, that a Scotch tune is not preferable.12

Hume suggests that if one’s ear has not been educated to the sophistication of Italian music, it will sound too intricate and therefore will not be a source of pleasure. His argument is emblematic of the transition from ideas of the ‘outer objectivity’ of beauty that held sway before the eighteenth century to the acknowledgement of inner human subjectivity that endows each person with the capacity for judgement and discernment based on their particular sensory experiences and environmental conditioning.

What I argue here is that by the eighteenth century not only had sensation become, as commonly acknowledged, a crucial element in matters of taste, but taste itself had acquired a prominent historical and cultural dimension.13 Taste came to be understood as a process shaped by the power of national customs. This mode of understanding culture depended on the new-found prominence of historical studies, a prominence which made Hume state, ‘I believe this is the historical Age, and this the historical Nation.’14 Authors such as Robertson, Ferguson, Hume, Smith, Kames, and Millar all contributed to the development of historical narratives where the analysis of social and economic factors and of the influence these had on political institutions and laws became crucial to the understanding of developing processes, lending their histories a peculiar and innovative flavour. These new historical discourses were informed by ideas about the development of civilization as well as by an extensive acquaintance with travel literature. Implicit in Hume’s remarks is the idea that the refinement of musical taste brought by civilization brings about the transition from simple (and therefore more ‘natural’) tunes to complex (by which is usually meant Italian and especially polyphonic) music. These became common assumptions throughout the literate classes of Europe. Linked to this idea was the assumption that the diversification of tastes and cultures occurred more particularly in later historical stages, whereas the ‘state of nature’ must have been the same for the whole of mankind.15 In this context, Hume’s theories, as developed in his essay Of National Characters, were deeply influential, as was the British reception of Rousseau’s writings. These ideas contributed to the birth of the concept of ‘national musics’, which flourished in the British (and especially Scottish) context and was canvassed extensively by German writers. Silvia Sebastiani characterizes the role of history in shaping Scottish Enlightenment ideas about human society as follows:

In ordering human societies on a continuum from savagery to civilization, diversity – of tasks and occupations, as well as characters – became a specific product of history … . Nation gradually became a historical and cultural category, reserved to describe the political and social divisions of Europe: it came to be associated with a heritage of social customs and beliefs, linked to a political unit, which shapes the cultural variety of more advanced peoples. It is in the eighteenth century, then, that nations acquired the sense of linguistic and cultural communities, of ‘imagined communities’, as Benedict Anderson labels them.16

This view of history as a succession of stages soon gained its own name: conjectural history. Dugald Stewart described it as a history arising out of comparisons between ‘our intellectual acquirements, our opinions, manners, institutions, [and] those which prevail among rude tribes’.17 This new approach to history was inaugurated by Adam Smith’s Lectures on Jurisprudence, which he delivered at Glasgow University in 1763.18 It had an immediate impact on discussions of music history, producing a narrative of musical progress from simpler forms of monophonic music to the development of counterpoint and polyphony, where each of these musical stages was linked to a specific place in a civilizational hierarchy. Conjectural history destabilized classic understandings of ancient music, making it appear as the product of barbarous times: the music historian Charles Burney openly stated that had someone told him the extant pieces of ancient Greek music were actually the products of Cherokees or Hottentots he would have had no trouble believing it.19 The ancient Greeks became a primitive Other, comparable to the newly discovered tribes of the South Seas.20

It was not just the ancient history of music that was reordered by this new approach to history. Contemporary Scottish Highland culture was recast as a primitive Other in these new models of history. While ancient Greece could only be the subject of conjecture, music of the Highlands could be observed and studied as a window onto a primitive past, untouched by modernity. These variously labelled Others were supposed to be testimonies of the ‘infancy of mankind’, being located in an initial stage of civilization and, therefore, being nearer to the ‘real nature’ of humankind. This primitive relation to nature would find great cultural significance in light of the spread of Rousseau’s ideas about civilization and the sublimity of ancient languages throughout Europe. Combined with the emergence of travel literature, British elites took great interest in the national past, and musical primitivism became a fashionable trend. While the popularizers of the latter ‘sought out and privileged those societies in which they could perceive the qualities of natural men’, it is also true that ‘the motivation for such an engagement, and the sort of locations in which natural man was to be found, differed … across Europe and through the course of the century’.21

A key question of these inquiries into the characteristics of humankind in the ‘natural state’ or in the infancy of civilization was: what kind of music does such a man enjoy? Hume claimed that an unrefined man would not appreciate the intricacies of Italian music and would prefer a Scotch tune. This idea reflected the British belief the folk music of the Scottish Highlands and Lowlands was closer to the primitive, natural state of man. Primitivists across Europe sought out sources of simpler and hence more natural music that could be contrasted with the overly refined customs of national elites and the educated classes of Europe. Rousseau fought his battle against French music, grounding his critique in the specific musical properties of national languages, which he argued acted powerfully on their ‘potential for melody’, and across the Channel it was the music of Italy that became symbolic of a more natural music, which could please even an uneducated audience.22

In Britain, unlike France, Italian music came to symbolize luxury and ‘effeminate refinement’, and hence could not be discussed in Rousseauian terms: in Fergusson’s poem ‘On the Death of Scottish Music’ the author decries how Italian ‘sounds’ have supplanted Scottish ‘saft-tongu’d melody’.23 One notion of Rousseau which gained wide currency was the idea that simple melody stood at the root of what was natural, and therefore universal, in music. But the precise identification of such natural melodies varied from country to country. In the words of Gelbart, Rousseau’s ‘search for simplicity and for supposed natural qualities in music, tied to his theorizations about its history, exerted a mighty influence on a generation of scholars who were seeking to trace the common roots of humanity and uncover the universals of human nature buried beneath the veneer of modern civilization.’24 Gelbart continues to note that the claims of musical universalism, previously (as in Rameau’s theory) based on the idea that music reflected a broad natural order, turned into the idea that music was natural to men in that it stood at the origins of language.25

Among scholars, simple thus became a meaningful yet ambiguous term for understanding folk music. Hume dedicated some thoughts to the subject in his essay Of Simplicity and Refinement in Writing, which opens with a quotation from Addison: ‘Fine writing consists of sentiments, which are natural, without being obvious.’ The natural and the simple, therefore, are not synonymous with poverty of expression or with obviousness. Hume observes that it is not the nature of the subject that makes writing fine but the way it is handled: ‘if we copy low life, the strokes must be strong and remarkable, and must convey a lively image to the mind’.26 Indeed, of simplicity and refinement, Hume prefers the former.

This longing for simplicity and nature found many outlets in the eighteenth century, but in the case of the intellectual thread we are following, there are at least three interconnected themes: simplicity indicated a closer relation to nature; a closer relationship to nature indicated a closer relation to natural ways of expressing emotions; and emotions found voice through poetry or song.

In Britain, modern theories of language identified writing and speech as two entirely separate domains.27 According to Hudson, scholars ‘began to recognize more clearly the special powers of speech not possessed by written language, a development that led to a deeper appreciation of so-called “primitive” language in non-literate societies’.28 A new school of thought developed around the ideas of Rousseau and Thomas Sheridan which claimed that ‘the propagation of literacy and print culture had destroyed the expressive force of speech, rendering it toneless and cold’.29 These reflections provided a fertile soil both for intellectual endeavours, such as the one undertaken by Macpherson, who – in the words of Mulholland – created an ‘oral voice’ for the poet’s speech,30 and for a re-evaluation of popular songs. It was Scotland that spearheaded this new interest in the oral aspects of culture, political agenda, and the philosophical thought fuelling it: ‘From Thomas Gray’s “The Bard” (1757) to Macpherson’s Ossian poems to the proliferating editions of ballad collections like Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), eighteenth-century Britain saw a remarkable upswell of interest in ancient bards, ancient poetry, and a newly compelling vernacular antiquity.’31

What I want to stress here is that elements of the British soundscape that had existed for centuries, such as ballads and songs, suddenly came to the forefront of national debates as they became symbols of a culturally framed soundscape in Britain. Ballads and oral culture were not a popular subject of polite learning prior to the eighteenth century, and McDowell has recently shown that ‘even as antiquarians, proto-folklorists, poets, and others valorized certain kinds of oral tradition that they viewed as quaint and harmless, literate hostilities toward other kinds of oral tradition did not change’.32 But as ballads acquired a new cultural meaning, in light of their supposed insights into the origins and the making of national character and language, collective popular interest incorporated them as an active element of the contemporary soundscape. And when I use the term ‘collective’ I am not referring to only the learned world. For while ballad collecting was practised by many armchair scholars, others did real fieldwork;33 as McAuley has emphasized, ‘for every collector who published a collection, there were other individuals who provided songs, airs, background information, or an entrée into the communities whose repertoires were being collected. These individuals tend to go unmentioned, seldom appearing anywhere.’34 And it is not unlikely that a small Scottish hamlet receiving the visit of, say, a Walter Scott who came to listen to an old mother singing raised the curiosity and concern of those who became the subjects of such scholarly fascination. Being visited by song collectors could alter one’s own perspective on one’s singing traditions and could force a new kind of awareness on the people of the Scottish Highlands as their familiar songs were incorporated into the ‘oral tradition’ of a nation.35

Theories of perception, conjectural history, primitivism, theories of language, and interest in national origins all coalesced around the songs and ballads of Scotland and became a powerful piece of a conscious and deliberate process of national characterization. What is of interest here to the historian looking for forgotten soundscapes in search of the relationship between sound and sense is that the shared and sustained attention focused on the ballad tradition (and the fear and foreboding of its extinction) modified the way ballads and songs were integrated into polite discourse, and in turn this also altered the production and consumption of these popular genres.

Scottish Songs: From Streets and Performance to Collection and History

As I hope to have demonstrated, simplicity became a virtue among those dissenting from the supposed effeminizing influence of civilization and luxury.36 Poetry and music were closely connected to the ideas of simplicity and nature through the medium of ‘song’, as songs, together with language, seemed to be elements shared by all human communities. As the century progressed and the interest in the natural conditions of humanity grew, so too did discussions about national songs. The music historian Charles Burney offers a revealing example in his travelogue The Present State of Music in Germany, in which he narrates an encounter with Lord Marischal (George Keith, c. 1693–1778), an exiled Jacobite:

as to music, he said, that I was unfortunate in being addressed to him, for he was such a Goth, as neither to know any thing of it, nor to like any music, but that of his own country bagpipes. On this occasion, he was very pleasant upon himself: here ensued a discussion of Scots music, and Erse poetry; after which, his lordship said, ‘but lest you should think me too insensible to the power of sound, I must tell you, that I have made a collection of national tunes of almost all the countries on the globe, which I believe I can shew you’. After a search, made by himself, the book was found, and I was made to sing the whole collection through, without an instrument; during which time, he had an anecdote for every tune. When I had done, his lordship kindly wrote down a list of all such tunes as had pleased me most by their oddity and originality, of which he promised me copies, and then ordered a Scots piper, one of his domestics, to play to me some Spanish and Scots tunes, which were not in the collection; ‘but play them in the garden, says he, for these fine Italianised folks cannot bear our rude music near their delicate ears.’37

This encounter is telling. National songs are here the object of polite conversation, but Lord Marischal seems to proceed cautiously, in order to see if his interlocutor, being ‘Italianised’, considers the topic worthy. The two men discuss the effects of music upon untutored ears: episodes relating to a Tahitian visitor to the Paris Opéra, to a Greek lady experiencing French and Italian opera for the first time, Scottish tunes and the ranz des vaches follow each other. Some of the noblemen and diplomats encountered by Burney in his tour around Germany told him they had made their own collections of national tunes, and Burney himself often asked his occasional informants to acquaint him with specimens of national music.38 All these topics were related to the idea of an Other nearer to nature, as well as to the new taste for the picturesque. As Ian Woodfield notes:

Majestic scenery and extraordinary natural phenomena such as the Giant’s causeway in County Arnim were beginning to attract widespread attention. Unfamiliar cultures (including some like the Irish that had hitherto been treated with scorn) were increasingly perceived as fruitful sources of exotic experience. Even barbarity, when viewed by the inquisitive traveller from a safe distance, could produce a kind of vicarious thrill. The most important musical expression of this movement came with the rapid growth of interest in ‘national airs’.39

The interest in these song collections came not only from inquisitive travellers looking for exotic experiences, but also from people interested in defining the cultural origins of their own nation. Cultural identity came to be defined by sounds and music as much as it did by clothing and eating.40 John Lettice, in Letters on a Tour through Various Parts of Scotland (1792), criticized the attitude of Englishmen touring Scotland, writing, ‘We are all Britons from the land’s end to the Orkneys … ; and God forbid that names or sounds, affectation, illiberality or prejudice should prevent the natives of Kirkwall and Penzance from regarding each other, as Britons and fellow citizens.’41 Names and sounds influenced the creation of a shared national identity, and recognizing a diversity of sounds – for here Lettice is primarily referring to language and accents – across the nation was necessary in inventing a shared British identity.42

A very famous example of sounds witnessing cultural identity is represented by William Hogarth’s The Enraged Musician (1741), in which he depicts the soundscape of London’s streets (see Figure 1.1). As Sean Shesgreen has observed, in designing this print Hogarth wanted to set his figures in a well-denoted, realistic London scene.43 So well did Hogarth capture the noise that Henry Fielding joked that this print ‘is enough to make a man deaf to look at’.44 In a solid house made of bricks, protected by a fence, we find the representative (significantly a male) of the art-music tradition: a trained musician playing the violin and reading his sheet music. The open window exposes the violinist to the sounds coming from the world outside. Stuck to the wall of the musician’s house we find a hint to another element of London’s official music life: ballad operas, a more socially inclusive form of opera than the Italian one. Ballad operas seem to feature here as a form of music in-between. They don’t belong to the interior of the house inhabited by the musician, but they still stick to its wall and find themselves behind the fence. The other figures of the picture are not protected by fences or walls. Among the purveyors of vocal mayhem we find two towering female figures: a street monger and a ballad hawker, the latter singing the ballad ‘The Lady’s Fall’ with a baby in her arms.45 Ballad singers were common in London’s streets. As Georg Lichtenberg noted in 1770, they ‘form[ed] circles at every corner’.46 Paula McDowell has stressed the importance of oral public discourse to popular political culture in London. In particular she has highlighted how forms of ‘oral advertising’ were ‘for the illiterate majority in England … the most regular source of news. While printed texts could be confiscated and censored, oral political culture was almost impossible to control.’47

Ballad singing was a typical female activity, with participants ranging from the London street ballad hawkers to field labourers and middle-class and aristocratic ladies.48 All those women sang in different places, for different occasions and using different repertoires, but the soundscapes they contributed to were increasingly associated with the cultural shape of a unified Britain. Travel literature of the time demonstrated the pervasiveness of song culture across the kingdom. The travelogues of Johnson and Boswell – A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775) and The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785), respectively – devote considerable attention to encounters with ballad singers of Erse songs.49 The attention given to these local soundscapes by such elite writers demonstrates the pervasiveness of debates about primitive music and the universal characteristics of language. This trend was so overwhelmingly popular that the ballad traditions of small, remote places that had gone largely unremarked upon throughout history now entered the pages of best-selling travelogues.

In the polite pages of the Spectator, ballads were defined as emblems of ‘Perfection of Simplicity of Thought’ and as ‘Paintings of Nature’.50 They were ‘not just sung from memory in the convivial setting of cottage fireside, but were also sold in the mean streets as the cheap goods of destitute beggars’,51 being a literary genre enjoyed, performed, and consumed by every social stratum. But if Addison at the beginning of the century still felt the need to justify a literary discussion of ‘Chavy Chase’ in the Spectator by making parallels with the Aeneid and classical poetry, subsequent writers discussed ballads without feeling the need to bother the Ancients’ authority: the fact that ballads were ‘the favorites of Nature’s Judges – The Common People’52 was sufficient ground to publish new collections. Collections, Steve Newman has argued, offered ‘a way to take advantage of the ballad’s circulation as a cheap commodity while framing it so that it remains tied to a common nationality. Constituting the ballad this way, authors begin to stage moments in which an elite mind is called through an encounter with popular song to know itself and its place in the nation.’53 Of course, this process did not leave the ballad genre unharmed: ‘elite minds’ selected and purged the material that was destined to represent (supposedly ancient) marks of Britishness and proceeded towards the ‘civilizing’ of ballads.54

Tunes have long been part of this history, and Matthew Gelbart identifies Allan Ramsay as ‘one of the first to understand the potential of literary and musical material, and especially material shared at least partly by the lower classes, for rallying people around a common identity’.55 Leith Davis maintains that whereas early publications of Scottish music focused on the creation of a ‘homogeneous sense of British culture with London as the cosmopolitan centre to the rustic (and disembodied) Celtic peripheries’, later collections had a different political agenda, giving Scotland a powerful cultural role in the newly unified nation.56 Once the Jacobite rebellions were mere memory and British unity was no longer under internal threat, underlining the nativeness and distinctiveness of Scottish music via its song culture enabled the periphery of the nation to gain prominence in the larger, multi-focal world of Britain.

As collections multiplied, a process of converting ballads’ speech into writing formed. As noted by Stewart:

the notion that writing endows the oral with materiality is another facet of the collector’s interest in establishing the ephemerality of the oral, an interest that puts the oral in urgent need of rescue … The external history of the ballad is thus inextricably bound up with the emerging notion of the ballad as artefact and the crisis in authenticity that results from the severing of this artefact from its performance context.57

Authenticity became a crucial issue among ballad collectors. By the second half of the century, this concern with authenticity led to changes in the practice of collecting ballads. Gelbart stresses that the Ossian debate accelerated a shift in the meaning of the ballad as a form of national music from being a ‘popular culture shared across classes’ to being a ‘relic from the past, something representing an ancient and untainted stage of society, a domain in which “authenticity” was central’.58 Ballad or song collections were not always printed with the tunes, and several notable collections (such as Ramsay’s Tea-Table Miscellany,59 Herd’s Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, Pinkerton’s Scottish Tragic Ballads, and Burns’s Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, which contained five songs) contained only the name of the tune to which the lyrics ought to be sung. Davis maintains that this kind of approach, ‘instead of positioning the author as producer and the reader as consumer’, required a reader from whom production was also expected, and that hence these examples do ‘not represent a separation of oral and print cultures or of the musical and the poetic’ but rather a ‘dynamic interaction as a challenge to conventional printed poetry’.60 This change marked a transitionary phase in the process of ‘endowing the oral with materiality’.

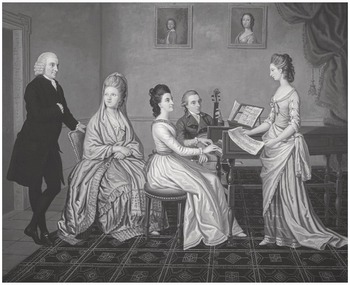

The ballad as musical, and not only literary, form still deserves closer scrutiny, but Una McIlvenna has emphasized – especially in her studies on execution ballads – how ‘balladry’s refashioning of well-known tunes had the potential to create an aural palimpsest wherein a new version of a ballad was given added significance by association with earlier versions set to the same tune’.61 The act of printing ballads and associating them with well-known tunes, only hinted at by the tune title, supplies additional evidence of a stage in which the culture needed to re-enact these songs was shared across classes. In the case of these collections, the problem of musical authenticity was completely avoided, but in the case of collections published with the tunes, authenticity became a problem which was at odds with marketing strategies: being faithful to the ‘simplicity’ of old songs would have meant publishing only their melodic line, without adding any bass line. But educated people who wanted to revive these songs in the context of familiar and social gatherings, such as the ones represented in the painting James Erskine, Lord Alva, and His Family by David Allan (1780; Figure 2.1), needed scores which provided fully written-out accompaniments, especially for the pianoforte, violin, or cello.

Figure 2.1 David Allan, James Erskine, Lord Alva, and His Family, 1780.

Davies has stressed how the power of notation enforced uniformity in the songs: ‘the songs were presented with musical accompaniment by non-traditional instruments … or, in many cases, lyrics were omitted completely and only the title was retained. The process of printing also changed the relationship between music, musician, and audience implicit in the original performance of Scottish songs.’62 The publications concocted by Urbani and Corri, who – being Italians – were of course peripheral to national interests and more focused on selling their collection, are examples of these types. In addition, in his Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs for the Voice, George Thomson presented a musical accompaniment for violin, cello, and pianoforte that was anything but ‘authentic’, although in a preface to an 1805 edition of his songs he ‘acknowledges that such accompaniments are not universally appreciated’.63 Ritson, in an antiquarian move, made the most radical choice by not adding any bass lines to the airs. Mentioning his debt to earlier collections and to his friend the composer William Shield for the music, he takes a position in the debate about authenticity, stating that:

The base part, which seems to be considered as indispensible [sic] in modern musical publications, would have been altogether improper in these volumes; the Scotish tunes are pure melody, which is not unfrequently injured by the bases, which have been set to them by strangers: the only kind of harmony known to the original composers consisting perhaps in the unisonant drone of the bagpipe.64

The issue of faithful song transcription and the harmonization of melodies that were not originally conceived according to the tonal system begins to appear in the eighteenth century. Rousseau’s ‘Musique’ in his Dictionnaire de musique doubted the seeming uniformity of several specimens of ‘national music’: ‘We will note in these pieces a uniformity in the modulation that will make some admire the soundness and universality of our rules, and will make others doubt the understanding and faithfulness of those who have passed down these airs to us.’65 And Shield, publishing the version of the ranz des vaches transcribed by Viotti (whom he names as ‘one of the greatest Violin Players who ever crossed the Alps’), seems even more aware of the problems of musical transcription, also in relation to rhythm, by endorsing and transcribing only this part of Viotti’s extended comment:

I have written the musick [of the ranz- des vaches] without marking any rhythm or measure: there are cases in which the melody ought to be unconfined, in order that it may be completely melody and melody only. Measure would but derange its effect. These sounds are prolonged in the space through which they pass, and the time they take to fly from one mountain to another cannot be determined. It is not rhythm and measured Cadence that will give truth to the execution of this piece; it requires feeling and sentiment.66

It seems clear that as these questions of authenticity and originality emerged in relation to musical transcription, and as examples of music from distant lands made their way to European shores, doubts about the supposed ‘naturalness’ of European musical theory and an awareness of the link between musical theories and practices and notational procedures began to surface.67

The interest in ‘national songs’, which brought about the collection of national airs, found its full intellectual legitimization in the writings of Herder. Dealing with the ‘armchair scholars’ who regard popular songs as mere trifles, he says:

if they could but experience more directly with the senses, they would acquire the potential to see with the eyes and understand with the heart. They would know that what touches the people is the most important … . When one removes these songs from the paper on which they appear in order to reflect on their context, their times, and the vital ways they touched real people, one gains just a bit of the sense of how they might still resonate … . More recently, the Scots … sought again to awaken their poetry through re-sounding … . The language, sound, and content of the old songs shape the way a people thinks, thereby leaving its mark on the nation.68

The interest in the origin of civilization, and in the origin of one’s own culture, along with the new fashion for direct or mediated travel experiences, helped to put the relationship between sounds and senses into historical perspective, making them a national phenomenon. This process involved a shift in the estimation of the cultural value of popular ballads, and their presence in the aural landscape of eighteenth-century Britain also underwent significant changes. What I wish to stress in this chapter is that the processes of rescuing – standardizing, censuring, regulating, forging – mentioned by Knox at the beginning of this chapter were due to a shift in cultural perspective. This change transformed the ballad from an element of the historical soundscape, previously ignored by the refined classes, into an emblem of national culture, a unifying feature of a united kingdom. Ballads and songs have always been there. Inquiring collectors have not.