Article contents

Peace is a form of cooperation, and so are the cultural technologies which make peace possible

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 January 2024

Abstract

While necessary parts of the puzzle, cultural technologies are insufficient to explain peace. They are a form of second-order cooperation – a cooperative interaction designed to incentivize first-order cooperation. We propose an explanation for peacemaking cultural technologies, and therefore peace, based on the reputational incentives for second-order cooperation.

- Type

- Open Peer Commentary

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Cambridge University Press

References

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science (New York, N.Y.), 211(4489), 1390–1396.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Fry, D. P., Souillac, G., Liebovitch, L., Coleman, P. T., Agan, K., Nicholson-Cox, E., … Strauss, S. (2021). Societies within peace systems avoid war and build positive intergroup relationships. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 17.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Garfield, Z. H., Schacht, R., Post, E. R., Ingram, D., Uehling, A., & Macfarlan, S. J. (2021). The content and structure of reputation domains across human societies: A view from the evolutionary social sciences. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376(1838), 20200296.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Garfield, Z. H., Syme, K. L., & Hagen, E. H. (2020). Universal and variable leadership dimensions across human societies. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(5), 397–414.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Glowacki, L., & Gonc, K. (2013). Customary institutions and traditions in pastoralist societies: Neglected potential for conflict resolution. Conflict Trends, 2013(1), 26–32.Google Scholar

Glowacki, L., & von Rueden, C. (2015). Leadership solves collective action problems in small-scale societies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1683), 20150010.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Gurven, M., Allen-Arave, W., Hill, K., & Hurtado, M. (2000). “It's a wonderful life”: Signaling generosity among the Ache of Paraguay. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(4), 263–282.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hamilton, W. D. (1963). The evolution of altruistic behavior. The American Naturalist, 97(896), 354–356.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Henrich, J., & Muthukrishna, M. (2021). The origins and psychology of human cooperation. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 207–240.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Lie-Panis, J., & André, J. B. (2022). Cooperation as a signal of time preferences. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1973), 20212266.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mell, H., Baumard, N., & André, J. B. (2021). Time is money. Waiting costs explain why selection favors steeper time discounting in deprived environments. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(4), 379–387.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998). Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature, 393(6685), 573–577.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Panchanathan, K., & Boyd, R. (2003). A tale of two defectors: The importance of standing for evolution of indirect reciprocity. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 224(1), 115–126.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2013). Why anticorruption reforms fail – Systemic corruption as a collective action problem. Governance, 26(3), 449–471.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Powers, S. T., Van Schaik, C. P., & Lehmann, L. (2016). How institutions shaped the last major evolutionary transition to large-scale human societies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1687), 20150098.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Singh, M., Wrangham, R., & Glowacki, L. (2017). Self-interest and the design of rules. Human Nature, 28, 457–480.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Sugiyama, L. S. (2004). Illness, injury, and disability among Shiwiar forager-horticulturalists: Implications of health-risk buffering for the evolution of human life history. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 123(4), 371–389.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

von Rueden, C. (2014). The roots and fruits of social status in small-scale human societies. In J. Cheng, J. Tracy & C. Anderson (Eds.), The Psychology of Social Status (pp. 179–200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0867-7_9CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Yamagishi, T. (1986). The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 51(1), 110.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

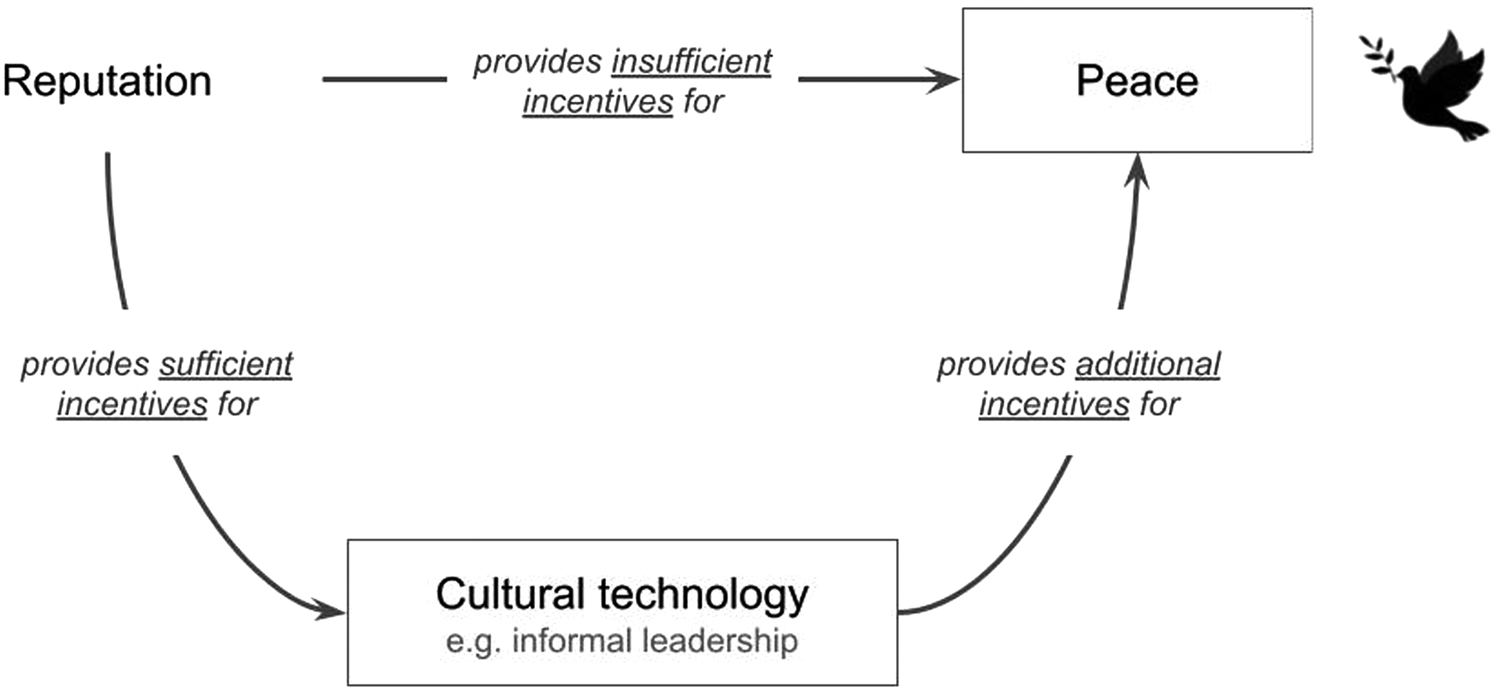

Figure 1. An explanation for peace through cultural technology.

This is an insightful analysis of the evolution of peace, using the lens of game theory. We propose to complement it, by exposing the cooperative dilemma underlying peacemaking cultural technologies. While necessary parts of the puzzle, cultural technologies are insufficient to explain peace – they replace one cooperative dilemma with another. We propose a solution based on prosocial reputation. Cultural technologies, such as informal leadership, may be designed to amplify reputational incentives – in which case they replace a difficult cooperative dilemma with one which is easier. This is not just theoretical nitpicking. Taken together, the author's account and our complement can generate testable predictions regarding the conditions under which peacemaking cultural technologies, and therefore peace, may evolve.

As the author rightfully points out, peace is the solution to a cooperative dilemma. In small-scale societies as well as in decentralized urban gangs, war, like defection, exacts a toll on the entire group; yet it is beneficial for certain individuals. If nothing keeps these individuals in check, war is the only Nash equilibrium.

Implicit in this account however, is that peace cannot be explained by reputation – or other canonical explanations for cooperation, such as kin altruism (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1963) and reciprocity (Axelrod & Hamilton, Reference Axelrod and Hamilton1981). In the iterated prisoner's dilemma that the author considers, cooperation is a Nash equilibrium when the benefit of a prosocial reputation exceeds the temptation to cheat (Nowak & Sigmund, Reference Nowak and Sigmund1998; Panchanathan & Boyd, Reference Panchanathan and Boyd2003). War ends up being the only Nash equilibrium because certain individuals find it beneficial to cheat even when considering the reputational cost of deviating from peaceful behavior. In other words, peace can be characterized as the solution to a hard-to-solve cooperative dilemma – a cooperative dilemma for which reputation provides insufficient incentives.

To achieve peace, humans need to create additional incentives. The author rightfully insists on the central role played by cultural technologies – norms, social structures, mechanisms, and institutions, which change the underlying incentive structure (Henrich & Muthukrishna, Reference Henrich and Muthukrishna2021; North, Reference North1991; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Powers, Van Schaik, & Lehmann, Reference Powers, Van Schaik and Lehmann2016). Humans rely on cultural technology to change the rules of the game, and invent peace. To quote the author, peace becomes a possible solution when “decentralized societies begin to develop internal social structures, including age or status groups, or informal but powerful leadership” (target article, sect. 4, para. 2).

Yet, the author does not mention that cultural technologies are themselves the solution to a cooperative dilemma. Age, status groups, and informal leaders need not necessarily work toward the objectives of the group. Instead, they can advance their own objectives. As the author acknowledges, even though they often promote cooperation within the group (Garfield, Syme, & Hagen, Reference Garfield, Syme and Hagen2020), for example, by working toward peace (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Souillac, Liebovitch, Coleman, Agan, Nicholson-Cox and Strauss2021; Glowacki & Gonc, Reference Glowacki and Gonc2013), informal leaders sometimes use their power and influence to promote their self-interest at the expense of the collective (Singh, Wrangham, & Glowacki, Reference Singh, Wrangham and Glowacki2017).

Cultural technologies are a form of second-order cooperation – a cooperative interaction aimed at promoting cooperation (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Persson, Rothstein, & Teorell, Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013; Yamagishi, Reference Yamagishi1986). In and of themselves, they are insufficient to explain peace. Cultural technologies allow humans to solve the first-order cooperative dilemma. Yet, they introduce another, second-order cooperative dilemma in its place. It seems we are back to square one.

Our solution is to view cultural technologies as technologies specifically designed to leverage reputation. Cultural technologies need not lead us back to our starting point, because second-order cooperation need not be as hard-to-solve as first-order cooperation. Humans can design cultural technologies which: (i) provide sufficient incentives for the hard-to-solve cooperative dilemma, and (ii) are themselves underlain by an easy-to-solve cooperative dilemma, that can be stabilized by reputation. When this is the case, cultural technologies (and reputation) can explain peace (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An explanation for peace through cultural technology.

Informal leaders, for instance, seem decidedly incentivized by reputation. Across small-scale societies, leadership is associated with social status and prestige (Garfield et al., Reference Garfield, Schacht, Post, Ingram, Uehling and Macfarlan2021). Leaders tend to enjoy high-social capital (Glowacki & von Rueden, Reference Glowacki and von Rueden2015), and high-social and material benefits (Garfield et al., Reference Garfield, Syme and Hagen2020; Gurven, Allen-Arave, Hill, & Hurtado, Reference Gurven, Allen-Arave, Hill and Hurtado2000; Sugiyama, Reference Sugiyama2004; von Rueden, Reference von Rueden2014). Leaders have a lot to lose by defecting. If they cheat, and promote self-serving warfare at the expense of the collective, they stand to lose their very position, and all its accompanying benefits.

In line with the author's account, there is nothing specific about peace or peacemaking cultural technologies. Cultural technologies allow humans to scale up cooperation – beyond the limited scope of what can be achieved with reputation alone. Our complement further clarifies the “ironic” logic of peace uncovered by the author. Peace with another group is just one instance of large-scale cooperation. War along that group against another coalition is another such instance. Both depend on the ability to stabilize cultural technologies, that is to solve a second-order cooperative dilemma.

We can derive testable predictions from this idea. Cooperation is not infinitely scalable, because second-order cooperation cannot be made infinitely cheap and still provide sufficient incentives for first-order cooperation. We expect higher ability to establish peacemaking cultural technologies, and therefore peace, when individuals have a stronger incentive to invest in their prosocial reputation – for example, in long-standing communities, in which the shadow of the future looms large (Axelrod & Hamilton, Reference Axelrod and Hamilton1981; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990), or in contexts of material security, in which individual's immediate needs are already met (Lie-Panis & André, Reference Lie-Panis and André2022; Mell, Baumard, & André, Reference Mell, Baumard and André2021).

Financial support

This research was funded by Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-17-EURE-0017 and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02).

Competing interest

None.