There is no Enga word for peace…. (Wiessner, Reference Wiessner2019, p. 231)

The “Tauade not only have no word for peace but display no awareness of a social order that is ruptured by violence.” (Hallpike, Reference Hallpike1974, p. 74)

1. Introduction

The debate about the origins of war and peace in the human lineage is at an impasse over whether our evolutionary history is best characterized by lethal intergroup aggression (war) or peace. One perspective argues that a state of lethal hostility between early human groups characterizes most of our evolutionary history (Gat, Reference Gat2009; Keeley, Reference Keeley1996; van der Dennen, Reference van der Dennen2002; Wrangham & Glowacki, Reference Wrangham and Glowacki2012), while the other argues that peace extends deep into our lineage with war only recently coevolving with increasing social complexity and agriculture (Fry, Reference Fry, Sussman and Cloninger2011). I propose a different approach, instead asking what are the preconditions necessary for humans to have sustained positive-sum intergroup relationships and when were they likely to have emerged? Answering these questions involve considering the costs and benefits of intergroup cooperation and aggression, for yourself, your group, and your neighbor. Taking a game theoretical perspective provides new insights into the difficulties of removing the threat of war, but also reveals an ironic logic to peace – the factors that enable peace also facilitate the increased scale and destructiveness of conflict.

Humans are unusual for the range of our intergroup relationships which can include affiliation and altruism toward strangers as well as destructive large-scale wars. While other social species such as dolphins and bonobos may have affiliative relationships between groups (Danaher-Garcia, Connor, Fay, Melillo-Sweeting, & Dudzinski, Reference Danaher-Garcia, Connor, Fay, Melillo-Sweeting and Dudzinski2022; Elliser, Volker, & Herzing, Reference Elliser, Volker and Herzing2022), sustained positive-sum relationships that cross pronounced group boundaries are exceedingly rare among nonhuman animals likely appearing only in a few eusocial insect species. Our cousins the bonobos often have affiliative interactions with other bonobo groups that include grooming, sex, and sometimes food sharing (Lucchesi et al., Reference Lucchesi, Cheng, Janmaat, Mundry, Pisor and Surbeck2020; Samuni, Langergraber, & Surbeck, Reference Samuni, Langergraber and Surbeck2022). Less well known is that violence is common when two bonobo groups meet. Of 92 intergroup encounters in the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, 34% of them included physical aggression with 15% resulting in injuries to at least one bonobo (Cheng, Samuni, Lucchesi, Deschner, & Surbeck, Reference Cheng, Samuni, Lucchesi, Deschner and Surbeck2022). At the LuiKotale site, intergroup encounters between bonobo groups “were more aggressive than tolerant” with 47% of the intergroup encounters having “large-scale coalitionary aggressive events” often resulting in injuries (Moscovice, Hohmann, Trumble, Fruth, & Jaeggi, Reference Moscovice, Hohmann, Trumble, Fruth and Jaeggi2022). Among nonhuman social animals that engage in lethal intergroup conflict, including banded mongoose, wolves, chimpanzees, and meerkats, there is little evidence that any of these species exhibit behaviors approaching the positive-sum, tolerant intergroup interactions that humans frequently have.

The scale and scope of our conflicts are shaped by the social groups they involve, but humans are also members of multiple social groups simultaneously with overlapping nonexclusive boundaries (e.g., family, larger kin group, neighborhood, university community, city, religious organization, political party, and nation). Conflict can occur either within any of these groups, such as when factions of an extended family feud, or between groups, such as when one religious sect persecutes another. For these reasons, I avoid the distinction sometimes made between internal and external warfare because it does not capture the difficulty of achieving peace or the intensity of warfare. Instead, I focus on violence and peacemaking between social groups – whether those are bands, residential communities, clans, or tribes.

Our capacity to interact with members of other social groups peacefully is an important factor in our species' success (Fuentes, Reference Fuentes2004), facilitating the spread of ideas, materials, and goods across group boundaries, contributing to cumulative cultural evolution (Sterelny, Reference Sterelny2021). Intergroup exchange allows us to build the cultural technologies to adapt to a seemingly endless variety of ecological and social environments. Periods of peace may also fuel increased social complexity due to expansion of exchange between groups that would otherwise be in conflict (Wiessner, Reference Wiessner1998, Reference Wiessner2019). The challenge of building peaceful intergroup relationships is formidable because peace requires coordinating the interests of every individual to favor nonaggression, while intergroup aggression can be unilaterally initiated but subsequently involve the entire group.

I argue that peace is the product of cultural technologies that depend on factors that are likely to have only recently emerged in our species' history, including social institutions and cultural mechanisms for preventing and resolving conflicts. I focus on decentralized or small-scale subsistence societies, such as hunter–gatherers and horticulturalists, because they are the most relevant to understanding the origin of peace in human evolution. This is because for much of our history we lived in small unstructured groups lacking centralization and complex social institutions. While there is strong evidence that humans evolved to be tolerant of out-group members and form cooperative relationships with non-kin, my argument will show we did not evolve an innate capacity for peace. Rather, our capacity for flexible relationships, cultural incentive systems, and strategic modification of behavior allowed us to develop the cultural technology for durable peace (cf. Kim & Kissel, Reference Kim and Kissel2018, who call it “peacefare”). Ironically the cultural tools that allow us to develop peaceful relationships are the very same ones that allow us to sometimes engage in total war. Thus, as Mead (Reference Mead and Bramson1940) famously said of warfare, peace, too, is an invention.

My argument is structured as follows. In the remainder of this section, I review previous approaches to the study of peaceful societies, and put forward an operational definition of peace that will guide the remainder of the article. In section 2, I argue that peace is best understood as a solution to a cooperative dilemma such, while in section 3 I explore the conditions that are required for peace. Section 4 describes the tensions between war and peace and section 5 reviews the relationship between states and peace in small-scale societies. In section 6, I review evidence for the origins of peace in human evolution, and section 7 describes the coevolution of peace and intergroup conflict. Section 8 attempts to explain why other mammals lack peace and section 9 explores variation in war and peace across human societies. I conclude in section 10 by arguing that our human ancestors were neither warlike nor peacelike but instead were like humans everywhere – they struggled to create peace, but could and did use aggression strategically.

1.1. Warlessness, peace, and cooperation

Previous research on peace has often categorized groups as either “warlike,” “warless,” or “peaceful” and argued that “peaceful societies should lack whatever instigates war” (Kelly, Reference Kelly2000, p. 11). One limitation with this approach is that the absence of war does not necessarily constitute peace and the lack of war tells us little about the nature of interactions between groups and the factors underlying those relationships (van der Dennen, Reference van der Dennen2014). The two main explanations for warlessness among small-scale nonstate societies in the ethnographic record are isolation and subordination, neither of which is synonymous with peace.

First, groups without war are often geographically isolated. Geographic isolation, often combined with small population size was the most important predictor of low rates of intergroup violence in precontact Polynesian societies where the most “peaceful societies were located more than 100 kilometers from their nearest neighbor” and had under 1,000 individuals (Younger, Reference Younger2008, p. 927). The Copper Inuit are often used as an example of a peaceful society but also had “500 miles of barren coastline [that] separated the Copper [Inuit] from their nearest neighbors…” (Jenness, Reference Jenness1921, p. 549). Inuit groups that did live near other groups often had lethal intergroup violence with high casualty rates (Burch, Reference Burch2005).

Second, warlessness commonly results from the threat of violence from stronger groups, resulting in avoidance or subservient cultural roles. The Semai in Malaysia are regularly used as an exemplar of peaceful hunter–gatherers because they have low or nonexistent levels of violence toward non-Semai: “Their worldview, and humanity's place in it, does not include any violence” (Semai, Peaceful Societies, 2022). However, their peacefulness appears to be strongly influenced by the military superiority of the surrounding agricultural groups. The Semai “openly and often express fear that outsiders will attack them. They… teach their children to fear and shun strangers, especially non-Semai” (Dentan, Reference Dentan and Montagu1978, p. 97). One Semai man remarked that “If we had weapons, we'd drive the Malays off our land (aims an imaginary rifle, squinting and grinning)” (Dentan, Reference Dentan, Kemp and Fry2004, p. 169). The “Semai have learned that… counterviolence is useless; one just gets hurt again, they say. That does not mean that people… never fantasize about fighting against Malay. In fact, in the past when conditions were favorable, they have actually mounted violent resistance… Most of the time, though, they just do not think physical violence will work. Why get hurt for nothing?” (Dentan, Reference Dentan, Kemp and Fry2004, p. 173).

So common is the pattern of stronger groups completely dominating weaker groups that Helbling (Reference Helbling2006) argues most cases small-scale societies lacking war are best categorized as “enclaves,” in which militarily subordinate groups retreat to inaccessible forest and mountain areas. Service (Reference Service1971, p. 35) remarks that “Nowadays [hunting-gathering bands] are enclaved among more powerful neighbors… and they cannot but lose or be heavily punished for any breach of the peace. They are better called ‘The Helpless People’ or ‘The Defeated People’.” Many of the groups that are typically used as exemplars of peaceful societies such as the Semai, Hadza, Mbuti, !Kung, Ju/’hoansi, G/wi, Paliyans, Batek, and Amish are enclaved and surrounded by more powerful neighbors.

Rather than classifying societies as “peaceful” or “warlike,” a more fruitful approach is to examine relationships between groups, focusing on the factors that shape harmonious positive-sum relationships (Baszarkiewicz & Fry, Reference Baszarkiewicz, Fry and Kuntz2008; Kissel & Kim, Reference Kissel and Kim2019). The definition of peace I use is modeled on Anderson's (Reference Anderson2004) and Helbling's (Reference Helbling2006) positive and negative conceptions of peace and tries to capture a general state of interactions between groups. Peace is a condition where ongoing interactions between different social groups are marked by the absence of or infrequent occurrences of aggression and violence, alongside the expectation and presence of generally harmonious relationships not enforced with the threat of violence. Accordingly, peace is an ongoing state of interactions between members of different groups (whether kin group, clan, band, tribe, etc.), characterized by harmonious interactions where conflicts are generally resolved and are expected to be resolved without violence. A society may have peace with one group while having violent interactions with another group. This definition does not require the complete absence of aggression or violence in intergroup interactions, only that violence is rare, unexpected, and quickly resolved.

1.1.1. Cooperative relationships do not imply an absence of war

Intergroup cooperation is likely universal across human societies, including among societies with high rates of war and violence. While cooperation, including trade, may promote peace, the presence of cooperation alone is not evidence that war between groups is absent. This is an especially important point when examining the archaeological evidence of intergroup relationships. Cooperation, including trade and marriage, can occur in the context of broader intergroup hostilities or large power asymmetries, such as those in patron–client relationships where the weaker parties act in a context of intimidation (as the Semai appear to be). In cases of active hostilities between two populations, individual parties often continue to cooperate across group boundaries, exchanging information, materials, or goods. Thus, archaeological and ethnographic evidence of cooperation alone is not satisfactory for demonstrating the absence of war, even though intergroup cooperation can enable peace, and peace expands the potential for cooperation (Keohane, Reference Keohane2005).

2. Peace as a solution to a cooperative dilemma

2.1. The structure of decentralized war

Understanding how peace is achieved in small-scale decentralized societies requires first understanding how and why individuals participate in war in these same types of groups. Small-scale decentralized societies have a fundamentally different pattern of conflict than state societies with militaries (Wright, Reference Wright1942). Counterintuitively, the individual costs of participation in war appear to be relatively low and the potential marginal benefits significant. Small-scale warfare is acephalous and decentralized, occurring without formal leadership or chains of command, mechanisms to compel participation, and mechanisms to restrain conflict. Membership is typically ad hoc, composed of available people who want to participate, and leadership is informal, situational, and noncoercive. Unlike militaries which can involve years of compelled participation, small-scale warfare lasts for the duration of the event – hours to days – after which the participant returns to their ordinary life. Raiding parties often form without consent or even the knowledge of the larger social group, coordinated by one or two people who convince others to join them.Footnote 1 Unlike warfare in state societies, war in small-scale societies does “not seem to be carried out with any global strategy in mind” (Tornay, Reference Tornay1979, p. 114).

The most common pattern of war is the raid, primarily composed of young men. Raids are usually undertaken to fulfill the proximate goals of the raiders themselves which may include revenge, capturing loot, or gaining status. Raiding parties use strategic timing and ambush to attack one or two victims at very low risk to themselves, usually while the victims collect water, do daily activities, or exit their village in the morning (Gat, Reference Gat1999). The victims may be members of another ethnolinguistic community or members of the same ethnolinguistic community, but of a different lineage or clan (as in feuding). Because the primary tactic in small-scale war is surprise, raiders can choose to attack when the odds heavily favor their success. As a result, attackers on raiding parties face an extremely low risk of being killed or injured during an attack (Beckerman et al., Reference Beckerman, Erickson, Yost, Regalado, Jaramillo, Sparks and Long2009; Chagnon, Reference Chagnon1988; Glowacki et al., Reference Glowacki, Isakov, Wrangham, McDermott, Fowler and Christakis2016; Mathew & Boyd, Reference Mathew and Boyd2011; Wrangham & Glowacki, Reference Wrangham and Glowacki2012). A similar pattern is found in chimpanzees, who also form raiding parties that attack members of other groups when they have a significant imbalance of power (approximately eight attackers to one victim) with little evidence of chimpanzee attackers being seriously injured or killed (Wilson & Wrangham, Reference Wilson and Wrangham2003; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Boesch, Fruth, Furuichi, Gilby, Hashimoto and Koops2014). When there are casualties among human attackers, it is usually because they are detected and ambushed while traveling to the site of their intended raid but such accounts are rare (Wrangham & Glowacki, Reference Wrangham and Glowacki2012). Despite the low risk to attackers, members of raiding parties still must overcome fear and confrontational tension (Collins, Reference Collins2009; Mathew & Boyd, Reference Mathew and Boyd2011; Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2007). “This fear is curious because there is no memory of any Wao raider being killed, or even seriously injured, by the Waorani he attacked” (Beckerman et al., Reference Beckerman, Erickson, Yost, Regalado, Jaramillo, Sparks and Long2009, p. SI: 1). While the risks to attackers on raids are low, the overall mortality rates from intergroup violence can be high, though the severity is primarily driven by victims of raiding parties rather injuries to attackers.

Thus far we have described the most common pattern of small-scale warfare that has close parallels to intergroup conflict in chimpanzees. As societies increase in sociopolitical complexity, they often adopt more structured forms of intergroup violence, such as battles (Dye, Reference Dye2009, Reference Dye2013; Glowacki, Wilson, & Wrangham, Reference Glowacki, Wilson and Wrangham2020), which cangreatly increase the mortality rate of attackers as well as the chances of the defenders being successful (Dreu & Gross, Reference Dreu and Gross2019). Structured organized conflict such as high-risk battles presents a different set of strategic dynamics that may better approximate the conditions under which states wage war than the pattern commonly found in decentralized societies (Buckner & Glowacki, Reference Buckner and Glowacki2019).

2.2. The individual benefits to attackers

Attackers in small-scale warfare often benefit personally from their participation through private incentives. Status is almost universally accorded to warriors, thus war often provides an important arena for men in the same society to compete with each other for status (Gat, Reference Gat2009; Glowacki & Wrangham, Reference Glowacki and Wrangham2013; Wright, Reference Wright1942). Across societies, even among mobile hunter–gatherers, warriors frequently take material plunder, including captives or goods (though mobile foragers appear to do so to a much lesser extent than other types of subsistence) (Cameron, Reference Cameron2011; Gat, Reference Gat1999, Reference Gat2000). Captives can be used as reproductive partners, for labor as slaves, or to expand one's kin networks through adoption. In the few cases where the individual benefits of warfare have been quantified, they appear to improve the reproductive opportunities of warriors (Chagnon, Reference Chagnon1988; Dunbar, Reference Dunbar1991; Fleisher & Holloway, Reference Fleisher and Holloway2004; Glowacki & Wrangham, Reference Glowacki and Wrangham2015; Hames, Reference Hames2020; Macfarlan, Walker, Flinn, & Chagnon, Reference Macfarlan, Walker, Flinn and Chagnon2014, Reference Macfarlan, Erickson, Yost, Regalado, Jaramillo and Beckerman2018). The specific mechanisms are likely to vary between societies ranging from increased access to bridewealth, opportunities to make alliances with people who may provide reproductive partners, increased desirability as a potential partner, or other cultural mechanisms (though see Beckerman et al., Reference Beckerman, Erickson, Yost, Regalado, Jaramillo, Sparks and Long2009, for a potential counterexample).

Even in instances where intergroup violence is not socially endorsed, attackers still often receive social benefits from their peers. The ethnography of small-scale societies is replete with examples in which intergroup violence is subject to general reprobation or even punished, but a smaller subset of society may laud warfare, providing the attackers with status among their peers. In the absence of material or social incentives, war can provide endogenous motivations through “offer[ing] excitement not found in the village” (Westermark, Reference Westermark1984, p. 116). “Old informants speak about the pleasurable excitement in preparing for and setting out on a… raid…. [which] might even have been welcomed as a break to long, tedious hours of work…” (Dozier, Reference Dozier1967, p. 78). Thus, even if society at large does not accord warriors with prestige, and war is unlikely to result in captured loot, warriors may still be endogenously motivated to participate in raids.

2.3. The collective costs and benefits of war

War is bad and nobody likes it. Sweet potatoes disappear, pigs disappear, fields deteriorate and many relatives and friends get killed. (Pospisil, Reference Pospisil1963, p. 89)

Despite the common assumption that warfare in human groups is driven by competition for natural resources, there is mixed evidence of a relationship between competition for resources and the intensity, frequency, or scale of war in small-scale societies (Adano, Dietz, Witsenburg, & Zaal, Reference Adano, Dietz, Witsenburg and Zaal2012; Scheffran, Brzoska, Kominek, Link, & Schilling, Reference Scheffran, Brzoska, Kominek, Link and Schilling2012). Many ethnographers argue that there is no relationship, as warfare commonly occurs in regions with abundant resources including territory. In many cases, successful groups may not acquire the territory of the defeated groups. Moreover, any territory acquired through war would be a collective benefit available to both warriors and nonwarriors, exacerbating the collective action problem of intergroup violence.

While individual warriors may benefit from participating in war, there are two major collective costs from warfare borne by all members of the attackers' group: The risk of being killed or injured in a revenge attack and decreased access to resources through reduced opportunities for intergroup contact and the creation of unused buffer zones. The desire for revenge is a major proximate cause of war in small-scale societies and often results in the deaths of more people than the initial offense (Boehm, Reference Boehm2012a; Walker & Bailey, Reference Walker and Bailey2013). After an attack, the most likely response from the attacked group is to launch an attack of their own against the offender's group, thus leading to tit-for-tat raiding. Because the specific identity of individual attackers is usually unknown, any member of the offender's groups will suffice as a target. As a result, the original attackers are usually at no or little more at risk of being a victim of revenge than any other group member. The risk of retaliation then falls on all group members, regardless of their participation in the initial intergroup conflict.Footnote 2

In addition to the risk of being killed in revenge, wars impose collective costs by reducing opportunities for trade, the exchange of information, and access to potential reproductive partners both within and between groups. While cooperation frequently continues across group boundaries during intergroup conflict, it is often reduced or severely curtailed as people avoid interacting with members of groups that are hostile to them. War also has the often-devastating effect of producing large unused border or buffer areas that people avoid (Evans-Pritchard, Reference Evans-Pritchard1957; Glowacki & Gonc, Reference Glowacki and Gonc2013; Turton, Reference Turton, Fukui and Turton1979). People may also flee areas at high risk of conflict even if those regions are resource abundant, losing access to valuable resources.Footnote 3 For subsistence populations, these large unused border zones can mean the devastating loss of access to productive game land, grazing areas, and water sources.

2.4. The cooperative dilemma of war and peace

I have shown that participation in small-scale war is low risk to attackers because of the strategic use of ambush and assymeteries in the number of attackers and defenders. At the same time, attackers are likely to receive important material and social benefits, especially status. The costs of war, however, are primarily borne by all members of the attacker's group, including the risk of retaliation, the creation of unused buffer zones, and the loss of opportunities that come from intergroup contact. As a result, a dynamic exists in which it may be individually beneficial to initiate intergroup violence because of the possiblity of receiving private benefits, but simultaneously costly for other members of the group.

The insight that war may be hard to avoid even when peace is the most beneficial strategy for a group as a whole has been long recognized (Schelling, Reference Schelling1980). In fact, efforts to make one's own group more secure may ultimately increase the likelihood of conflict. This is because other groups are likely to respond in kind, particularly when they have incomplete information (known as the security dilemma) (Blattman, Reference Blattman2022; Levy, Reference Levy1998). The dynamic between war and peace is commonly modeled as a prisoner's dilemma where any individual member may be better off defecting (initiating aggression against out-groups), but the entire group would be better off with peace (cooperating) (Cohen & Insko, Reference Cohen and Insko2008; Coombs & Avrunin, Reference Coombs and Avrunin1988; Rusch, Reference Rusch2013; Snyder, Reference Snyder1971; van der Dennen, Reference van der Dennen2014). Depending on the dynamics of the conflict, other cooperative dilemmas may better match the specific context, including games of chicken or the stag hunt, or attacker–defender games (Dreu & Gross, Reference Dreu and Gross2019; Dreu et al., Reference Dreu, Gross, Méder, Giffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016; Rusch, Reference Rusch2022; Schelling, Reference Schelling1980). Regardless of which cooperative dilemma is the best match for the specific group dynamics, the difficulty of limiting the payoffs of aggression by individuals is one of the most formidable barriers to the emergence of peace in small-scale societies.

Preventing conflict is difficult because a single act of aggression by one group member can be enough to trigger conflict (Fig. 1), as other members of the attacked group seek revenge. Thus peace requires coordinating the interests of all group members for nonaggression making sustained peaceful relationships difficult to achieve, especially once a conflict has started. “A fundamental reason for the perpetuation of cycles of raiding… was that a unilateral decision to cease fighting was impractical… so long as neighboring villages continued to be willing to fight” (Ploeg, Reference Ploeg, Rodman and Cooper1979, p. 143). It also means that even one individual acting unilaterally can determine the nature of intergroup relationships. As Clastres notes (Reference Clastres2010, p. 193), “The power to decide on… war and peace… no longer belong[s] to society as such, but… to the … warriors, which would place its private interests before the collective interest of society… The warrior would involve society in a cycle of wars it wanted nothing to do with.”

Figure 1. Peace as a prisoner's dilemma. Intergroup conflict can be studied as an iterated prisoner's dilemma. The key challenge to peace is developing payoff systems that favor cooperation by member of both groups that are resilient against real or perceived defection.

The payoffs from aggression are not symmetric across a population because individuals vary in how much they are likely to benefit from their participation. Young men, in particular, are especially prone to status-seeking behaviors, including acts of aggression, exacerbating the conditions for war (Yair & Miodownik, Reference Yair and Miodownik2016). While women in small-scale societies rarely participate in violence themselves, they often have an important role in encouraging men toward violence through teasing or ridiculing men who abstain from violence.

Thus, achieving peace requires solving an iterated cooperative problem like the prisoner's dilemma that each member of a group plays repeatedly in encounters with any member of another group. This dynamic is further exacerbated by the fact that war does not necessarily have to originate with unprovoked aggression but can instead arise from routine conflicts between individuals. Conflicts are an inevitable feature of social life no matter how pacific the cultural values. Any conflict has the potential to escalate, resulting in violence and triggering retaliation. Furthermore, peaceful exchanges or interactions may inadvertently result in the injury or death of a group member; an accidental death or injury may be interpreted as an act of aggression leading to retaliation and initiating a cycle of tit-for-tat war. Therefore, the conditions that give rise to peace must not only coordinate the interests of individuals toward cooperation but must also be tolerant and resilient against instances of real or perceived defection.

2.5. Relevance to centralized (state) warfare

My analysis focuses on intergroup violence in small-scale decentralized societies because these kinds of society best resemble our understanding of ancestral human groups. This analysis is both relevant to and diverges from warfare in centralized societies. In centralized societies such as states, or chiefdoms such as many Plains Indians, intergroup violence is typically directed through an organizational structure including chiefs, officers, or militaries. This organizational structure solves the coordination problems inherent in warfare by incentivizing and organizing combatants, preventing defection from cowardice and desertion (often through severe sanctions), and mitigating the risk of unprovoked aggression by group members. The organizational structure can also incorporate a global view of the group and use violence to achieve the goals of the group. Because of the centralization through which war is waged by states to advance the strategic aims of the group, the appropriate level of analysis is the group itself, not the individuals who compose the group (Schelling, Reference Schelling1980). Thus, Blattman (Reference Blattman2022, p. 17) writes about war in state societies, “Wars are long struggles…. Big groups are deliberative and strategic.”

This quotation highlights the fundamental difference between small-scale decentralized war and centralized war that underlies the game theoretical logic of war and peace: Whether the most appropriate level of analysis is the individual or the group. Small-scale war typically occurs through a raid that lacks any overall strategic objectives. Instead of raids being directed toward advancing the strategic objectives of the group, they are initiated to satisfy the often-short-term aims of the individual attackers, especially revenge and status. Although I focus on small-scale societies, similar dynamics are often found in decentralized urban violence (Buford, Reference Buford2001; Mays, Reference Mays1997; Shakur, Reference Shakur2007). Thus, the most appropriate level of analysis for the conditions of war in decentralized small-scale societies is the individual. It is the individual, notthe society that decides to initiate war.

Despite the differences between state and decentralized war, there are important similarities in the logic of war and peace. For both decentralized and centralized societies, peace is often more beneficial than war for both the group as a whole and the individuals within the group. Because of this, individuals often seek to maintain peace and prevent conflict. Many of the primary drivers of war are the same between decentralized and centralized societies (Blattman, Reference Blattman2022; Schelling, Reference Schelling1980): Individual actors who are able to initiate conflict without feedback from the group, such as group of young men who decide attack their neighbors in the case of a small-scale society or an authoritarian leader in control of the military (Putin) (Kleinfeld, Reference Kleinfeld2019); incentives for war that cannot be shared with the other group or are intangible, such as revenge or status (Levy, Reference Levy1998); and finally commitment problems. Groups cannot necessarily trust that their adversaries will honor their commitments toward peace, and to assume that the other side has cooperative nonaggressive intentions may leave them open for attack (Powell, Reference Powell2006; Walter, Reference Walter2009).

3. Prerequisites for peace

Given the difficulties in creating and maintaining peaceful relationships, I now consider the conditions that enable them. I will argue that intergroup peace in humans required evolving the psychological capacity to tolerate strangers and developing social mechanisms through which interactions between members of separate groups are governed by norms that stipulate nonaggression. At the same time, when conflicts do emerge, societies require the ability to resolve them and signal future cooperative intent. These systems need to have both enough resilience to withstand inevitable conflicts, and the ability to keep dyadic conflicts from spreading beyond the original parties and becoming coalitionary.

3.1. Capacity for tolerant interactions

Peace requires the psychological capacity for tolerant, nonaggressive interactions that cross group boundaries. While humans clearly have this capacity, many social species lack this ability. Chimpanzees, for example, rarely have tolerant intercommunity interactions; instead they usually avoid each other and when an imbalance of power exists, the larger group often aggresses the smaller group (Wilson & Wrangham, Reference Wilson and Wrangham2003). While bonobos do have intergroup aggression, they also have tolerant and cooperative intergroup relationships that can involve copulation and occasional food sharing. The fact that bonobos have intergroup tolerance suggests that the capacity for tolerance between groups may have developed early in the hominid lineage or even predate it. Once a capacity for tolerance was in place, social conditions such as the expansion of kinship networks (Chapais, Reference Chapais2009) or sanctions against overly aggressive individuals (Boehm, Reference Boehm2012b; Wrangham, Reference Wrangham2019) may have further increased our ability to tolerate strangers. Regardless of when a human capacity of tolerance emerged, intergroup cooperation requires the ability to tolerate strange individuals, something our chimpanzee cousins are incapable of. Thus, identifying when and how this ability arose will provide insight into the first crucial step necessary for peaceful intergroup relationships.

3.2. Payoff structure favors cooperation

War was not perpetual… Truces for hunting seasons were often made in the hunting areas between the combatants. (Hickerson, Reference Hickerson1962)

Peace requires the psychological ability to tolerate strangers but tolerance itself is not sufficient for peace. Peace also requires the motivation to interact with members of other groups (unlike most group-living species, in which groups generally avoid each other). Positive intergroup interactions will be favored when individuals of both parties can benefit from their interactions, such as by accessing resources that would otherwise be unavailable (Pisor & Gurven, Reference Pisor and Gurven2016, Reference Pisor and Gurven2018). In nonhuman social animals, the potential benefits from intergroup interactions include opportunities to interact with potential reproductive partners, infer information about groups for future transfers, or learn about the relative size and strength of neighboring groups (Pisor & Surbeck, Reference Pisor and Surbeck2019). These potential benefits would apply to early humans. However, as early humans developed a more specialized subsistence niche, especially one that depends on complementarity (extra-household food sharing) and cultural technologies (spears, traps, tracking), the potential benefits would have expanded leading to increased incentives for intergroup cooperation.

The creation of interdependencies would have greatly amplified the potential payoffs for intercommunity cooperation. A common form of interdependency among subsistence societies is one in which groups that depend on unpredictable and variable resources allow others to access resources in their territory in times of need, such as water, game lands, or grazing (Cronk & Aktipis, Reference Cronk and Aktipis2021; Glowacki, Reference Glowacki2020; Kelly, Reference Kelly and Fry2013a, Reference Kelly2013b; Pisor & Jones, Reference Pisor and Jones2021). A potentially more important form of interdependence would have developed when groups began to rely on nonlocal resources or goods that other groups had access to and that could be procured through trade or social relationships (Schulz, Reference Schulz2022; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Pisor, Aron, Bernard, Fimbo, Kimesera and Borgerhoff Mulder2022). In small-scale societies, these include material goods, such as tools, stones for toolmaking, and ochre, as well as cultural knowledge including religious, ceremonial, or ritual information.

If intergroup conflict disrupts access to goods or other benefits from other groups, group members have a strong incentive to avoid conflict. This occurred in the Solomon Islands, for example, where “it must have required extraordinary self-control… to withstand the tantalizing temptation of having a go at each other. The remarkable thing is that peace of any duration obtained. What probably occurred was that each side badly wanted what the other had to offer; these considerations overrode appetites for bloodletting for more or less extensive periods of truce” (Oliver, Reference Oliver1955, p. 296).

3.2.1. Specialization can fuel peace

Increasing material and cultural complexity often expands the opportunities for interdependence between groups (Ringen, Martin, & Jaeggi, Reference Ringen, Martin and Jaeggi2021; Spielmann, Reference Spielmann1986), increasing the potential payoffs from intergroup cooperation. Groups that rely on or value a greater range of materials, specialized tools, technologies, or immaterial cultural items, such as ritual or religious knowledge, experience potentially increased payoffs from intergroup cooperation. As groups can increasingly provide each other with valuable goods, information, or support, there will be more attempts at preventing conflict and restoring relationships afterward (Garfield, von Rueden, & Hagen, Reference Garfield, von Rueden and Hagen2019). Highly interdependent regions often developed ritualized trade and exchange systems to maintain peaceful relationships, such as the White Deerskin dance (Goldschmidt & Driver, Reference Goldschmidt and Driver1940), the potlatch (Goldschmidt, Reference Goldschmidt, Sponsel and Gregor1994), and Kula ring cycle (Malinowski, Reference Malinowski1920).

3.3. Norms promote intergroup interactions

The capacity for tolerance and the possibility of benefiting from interactions with out-groups creates the conditions for intergroup cooperation of the type seen in bonobos, but these alone are insufficient for peace. When severe or lethal violence is a possibility, as in chimpanzees and many human groups, individuals are more likely to avoid interactions or even engage in preemptive aggression. Thus, peace also requires the ability to have reasonable expectations about whether interactions with out-groups are likely to be neutral, aggressive, or positive (avoiding neutral and aggressive interactions and seeking out positive interactions). This depends on the ability to predict both the behavior of one's own group members and the behavior of members of other groups. But how do we reasonably anticipate the behavior of our group members and members of other groups? We do so by adhering to and enforcing norms regulating the behavior of our group members with the knowledge that the other group does the same.

3.3.1. Norms reduce uncertainty in intergroup relationships

The vast scale at which humans cooperate both within and between groups is fundamentally different than any other vertebrate species. This ability is enabled by a uniquely human capacity for norm compliance and enforcement (Chudek & Henrich, Reference Chudek and Henrich2011). Norms are prescriptive rules or expectations about behavior that are known by members of a community and enforced by the community (Knight, Reference Knight1992). Accordingly, with norms in place, community members are expected to act in socially prescribed ways. They and other community members are aware of these prescriptions for behavior and deviations from them enforced, often through external mechanisms that include some form of sanctions.

Norms mitigate the threat that potential aggression imposes on intergroup relationships because they can stipulate both how oneself and one's group members should treat members of other groups (such as with aggression or nonaggression) and how members of another group should treat oneself and one's own group members. Once norms governing intergroup behavior develop, they reduce the likelihood of unanticipated aggression for two reasons: (1) Norms allow individuals to calculate the anticipated payoffs of intergroup interactions based on the behavior of their group members and the behavior of the out-group (whether members of either group are likely to use aggression). Being able to assess how an intergroup interaction is likely to unfold promotes the interaction of strangers by removing uncertainty about the outcome of the interaction (whether it is likely to result in violence). (2) A critical threat to positive intergroup relationships occurs when one individual behaves in a manner that can be interpreted as being threatening or hostile. Norms buffer against the overinterpretation of the behavior of any one individual who may do something conflictual and provide a chance for the offending group to restore the relationship by enforcing the norm with sanctions. Thus, in interactions between members of two groups, if one individual does something aberrant, a reasonable inference is that the individual is not adhering to the norms governing intergroup interactions, rather than assuming that behaviors of other group members will be similar. Thus, norms facilitate intergroup interactions by increasing resilience if an actor deviates from the norm.

Consider two groups of strangers who meet for the first time with no prior knowledge of each other. Individuals have few, if any, expectations about how they will be treated by members of the other group (e.g., whether they will be treated as a friend, ally, enemy, or potential threat). They also lack expectations about how they should treat the members of the other group (e.g., with wariness, warmness, or hostility). In such cases, each interaction is negotiated spontaneously and tentatively, as in other primates, as each individual seeks to determine the likely behavior of out-group members and then adjusts their own behavior based on the signals and cues they detect from others in their group and the out-group. Interactions may be cooperative, or they may be conflictual; some individuals may be aggressive and others pacific; and the state of interactions often quickly changes. A small conflict can easily lead to a breakdown of the relationship. Norms solve the problem of uncertainty in interactions by providing guidelines about how oneself and one's group should treat members of the other group but require confidence that the other group holds similar norms.

An overlooked but critical aspect of norms is that they require seeing members of a group as just that, members of a group and not merely a collection of individuals, often termed social identity (Moffett, Reference Moffett2013; Smaldino, Reference Smaldino2019). Because norms require knowing how members of a group should act, they require the psychological ability to categorize persons, including oneself, as members of a group (Hechter & Opp, Reference Hechter and Opp2001; Sripada & Stich, Reference Sripada, Stich, Carruthers, Laurence and Stich2005), and the social structures to demarcate groups as distinct. Group identification may be based on physical features such as proximity, residence, or relatedness, or social structures such as band or clan membership, indicated through dress or decoration. The capacity to identify ourselves and others as members of social groups that share certain properties allows us to interact with strangers not just as strangers; instead, we can base our treatment of them on their group membership and expect them to do the same in return (Lew-Levy, Lavi, Reckin, Cristóbal-Azkarate, & Ellis-Davies, Reference Lew-Levy, Lavi, Reckin, Cristóbal-Azkarate and Ellis-Davies2018; McElreath, Boyd, & Richerson, Reference McElreath, Boyd and Richerson2003; Pope-Caldwell et al., Reference Pope-Caldwell, Lew-Levy, Maurits, Boyette, Ellis-Davies, Over and House2022). Once norms governing relationships with out-groups are in place for both interacting groups, individuals can be reasonably confident about how they will be treated by members of the other group and able to calculate whether the interaction will be positive.

The key insight is peace requires that individuals be able to not only tolerate and benefit from interacting with strangers but also anticipate that the interactions will be nonaggressive. Doing so on an ad hoc basis, such as when two groups of primates encounter each other often leads to avoidance rather than cooperation. If interactions do occur, they are usually tentative and commonly involve aggression, thus easily breaking down, as in bonobos. But once humans evolved the ability to identify themselves and others as a member of a group and to enforce norms, the conditions were in place for the development of norms about how to treat out-groups.

3.3.2. Norms to promote peace and punish spoilers

When I asked the Bodi, “will there be an end to the killing and warfare if you get many cattle and abundant pasture?” they replied “no, it will go on forever.” (Fukui, Reference Fukui, Fukui and Markakis1994)

Norms about how to treat out-group members may stipulate nonaggression, which promotes peace, or they may endorse violence toward out-group members which drives warfare. In small-scale traditional societies, violence toward out-groups was frequently tolerated or even rewarded through cultural incentives (Otterbein, Reference Otterbein1989). Multiple studies have found that the presence of norms for violence is associated with increased warfare and a lack of peace (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Souillac, Liebovitch, Coleman, Agan, Nicholson-Cox and Strauss2021; Glowacki & Wrangham, Reference Glowacki and Wrangham2013; Goldschmidt, Reference Goldschmidt, Sponsel and Gregor1994). The key challenge is for societies to prevent or replace norms that reward aggression, such as through providing status to aggressors, with norms that prohibit aggression and implement coercive sanctions for those who violate them. Fortunately norms can change and norms prohibiting violence can be adopted quickly (Pinker, Reference Pinker2012). In small-scale societies, shifts in norms toward nonaggression are often led by prominent individuals who negotiate for peace, renounce war, or refuse to honor warriors with blessings or other cultural rewards (Fry et al., Reference Fry, Souillac, Liebovitch, Coleman, Agan, Nicholson-Cox and Strauss2021; Glowacki & Gonc, Reference Glowacki and Gonc2013; Glowacki & von Rueden, Reference Glowacki and von Rueden2015; Strecker, Reference Strecker, Elwert, Feuchtwang and Neubert1999).

Norms for nonaggression toward out-groups require enforcement, often through sanctions against individuals who violate these norms. Strong sanctions for norm violators are difficult to enforce in small-scale decentralized societies, especially more egalitarian ones because punishment itself imposes costs, including the loss of a potential group member if the sanctioned individual changes their group residence (Baumard, Reference Baumard2010; Wiessner, Reference Wiessner2005). These societies can impose reputational sanctions, exclusion, or ostracism for norm violators, but these are often less effective than strong sanctions, such as fines, physical punishment, or even execution for those who break the peace.

Severe sanctions for norm violators typically occur in more complex societies with structures promoting social solidarity, such as age-sets, that invest a group of coevals with authority over their members (Garfield et al., Reference Garfield, Ringen, Buckner, Medupe, Wrangham and Glowacki2023; Mathew & Boyd, Reference Mathew and Boyd2011). Age-mates may be motivated to sanction peers who violate important norms, including breaking the peace, because the norm violation imposes reputational damage on the rest of the age group, thus avoiding the second-order free-riding dilemma (Baumard & Liénard, Reference Baumard and Liénard2011; Lienard, Reference Lienard2016). Similarly, in societies where older men yield significant social and political power, they may impose severe sanctions on peace violators. For instance, among the Daasanach of southwest Ethiopia “approximately 150 young Daasanach wanted to go to war… The plans of attack were disclosed and all the other age-sets… beat the youngest men with sticks and made them withdraw their plan” (Sagawa, Reference Sagawa2010, p. 101). Preventing unilateral aggression thus requires not only a general absence of norms toward unprovoked violence, but it also requires the will and capacity to sanction group members who seek war unilaterally.

3.4. Mechanisms to resolve conflicts

The Hamar are an eternal enemy, and between them and the Mela there are no means of settling conflicts and making peace. (Fukui, Reference Fukui, Fukui and Markakis1994, p. 37)

Resolving conflicts is the most serious challenge to the development and maintenance of peace in small-scale societies. Conflicts often spread beyond the original parties to include the larger social group creating a cycle of tit-for-tat violence making resolution even more challenging (Garfield, Reference Garfield2021). Even when individuals who have been aggrieved do not wish to seek revenge, the social pressures to do so may be enormous. There also exists the possibility that unintentional harm caused by out-group members will be misinterpreted as having aggressive intent, triggering intergroup conflict (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Examples of peacemaking rituals: (A) Andaman Islands: Peacemaking involves a ritualized dance between hostile groups where aggressive feelings are displayed culminating in an exchange of weapons (Radcliffe-Brown, Reference Radcliffe-Brown1922). (B) Enga: Distribution of compensation after a death, approximately 100 pigs were slaughtered and money distributed (courtesy of Polly Wiessner). (C) Peace agreements with Arbore and other groups in southwest Ethiopia involve symbolically blunting spears and (D) then breaking and burying the broken spears (Streker & Pankhurst, Reference Streker and Pankhurst2004).

3.4.1. Restitution and signaling cooperative intent

War [can be] triggered by an individual, [but] peace can only be re-established communally. (Girke, Reference Girke, Bruchhaus and Sommer2008, p. 202)

The key challenge after intergroup conflict is to prevent members of the aggrieved group from taking revenge. This often requires restitution to the aggrieved party for the harm they have suffered (see Table 1). This may involve in-kind exchanges, such as replacing stolen livestock with other livestock or the utilization of different currencies, such as providing the aggrieved group with a person from the offender's group (usually a young woman). Because blame is often ascribed to the group rather than the individual, restitution frequently comes from members of the perpetrator's group, rather than from the perpetrators themselves.

Table 1. Common conflict resolution mechanisms

Not only does the offending group have to offer restitution, but the aggrieved group must accept it as satisfactory. This negotiation provides another arena for conflict between groups as they determine an adequate level of restitution that satisfies both groups. For example, among the Kalinga, “kindreds [of the victim] are rarely satisfied with simply being paid off, and often retaliate by a counter-killing” (Dozier, Reference Dozier1967, p. 93). Reaching satisfactory compensation can be difficult, especially when tensions between groups are high.

At the same time, the offending group needs to signal cooperative intent, for example, that future interactions are likely to be positive and that the offender's actions do not represent a new norm on the part of the offender's group (Roscoe, Reference Roscoe and Fry2013). The need to signal cooperative intent is why peacemaking after a violent conflict often requires that the offending group execute one of their own group members. For example, among the Curripaco “lineage members decided to execute ritually their kinsman who had killed, rather than provoke a spate of tit-for-tat revenge killings” (Valentine, Reference Valentine, Valentine and Beckerman2008, p. 36). While among the Erbore of southwest Ethiopia, one elder reported “We brought about peace by allowing two Erbores…to be killed by our enemies. I, myself, have handed over one of our sons to be killed” (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2008, p. 16). Drastic actions such as the execution of the offender can signal to the aggrieved group that future interactions are likely to be positive.

Because restoring or creating peace requires the community to reaffirm norms of cooperation and nonaggression toward the out-group, peacemaking often involves many people from both groups meeting to discuss the conflict and its resolution, often engaging in symbolic ceremonies indicating resolution (Table 1). This will commonly involve eating and drinking together, as well as rituals that symbolize that the conflict has been resolved and neither party desires revenge. Groups may break or bury items related to conflict such as spears or weapons, believing that peace may hold as long as these items remain buried (Strecker, Reference Strecker, Elwert, Feuchtwang and Neubert1999). Symbolic gifts may be given between members of the opposing groups that indicate a desire for peace (Bacdayan, Reference Bacdayan1969). Such traditions also exist in centralized societies, including states, with militaries often indicating surrender by turning over ceremonial swords.

3.5. Third-party mediators and leadership

We have seen that restoring relationships after a conflict requires the ability to sanction peace violators, the coordination of compensation between groups, and the ability to signal cooperative intent. These are difficult conditions to satisfy especially in the context of an ongoing conflict. Two factors can greatly increase the likelihood of peace: Leadership and third-party mediators. Despite their potential efficacy, small-scale decentralized societies often lack strong leadership and third-party institutions due to their egalitarian nature.

Leadership facilitates peace because individuals who wield asymmetric power can prevent war or establish peace using their influence over others (such leaders can also use their influence to motivate warfare) (Garfield, Syme, & Hagen, Reference Garfield, Syme and Hagen2020). As a result, peace efforts in small-scale societies are frequently led by prominent individuals who motivate in-group members to maintain peace, sanction offenders, and negotiate with out-group members (Fry, Reference Fry2007; Fry et al., Reference Fry, Souillac, Liebovitch, Coleman, Agan, Nicholson-Cox and Strauss2021; Glowacki & Gonc, Reference Glowacki and Gonc2013). Some societies institutionalized the role of peacemaker into a position such as a peace chief or peace leader (Bacdayan, Reference Bacdayan1969; Goldschmidt, Reference Goldschmidt, Sponsel and Gregor1994; Moore, Reference Moore1990), who “appeared at the scene of battle… and attempted to induce disputants to come to amicable agreement” (Goldschmidt, Reference Goldschmidt1951, p. 326). However, these kinds of formal peace leaders occur more frequently in societies with significant social stratification such as the Kalinga and Cheyenne. The absence of prominent leadership who can negotiate for peace is a key impediment to the development of peace in decentralized societies.

Third parties have an important role in restoring relationships after conflict in small-scale societies, whether within or between groups (Fitouchi & Singh, Reference Fitouchi and Singh2023; Hoebel, Reference Hoebel2009). Third-party mediators may be customary leaders or institutions, such as groups of elders or other bodies of prominent individuals, while in contemporary contexts they are more likley to consist of government representatives or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (Box 1). They often facilitate the negotiations about compensation and restitution such that they are acceptable to both parties, rarely relying on punishment for restoring relationships (Fitouchi & Singh, Reference Fitouchi and Singh2023; Singh & Garfield, Reference Singh and Garfield2022; Wiessner, Reference Wiessner2020). The absence of strong third parties to facilitate conflict resolution can be a serious impediment to peace. For example, among Wanggular of Melanesia “De-escalation was difficult…. There was no intermediary party… who could assist the two hostile parties to agree on the size and content of the payment…. Thus it seemed almost impossible for Wanggularm to settle quarrels” (Ploeg, Reference Ploeg, Rodman and Cooper1979, pp. 170–171).

Box 1. Anatomy of a cycle of peace and conflict

I highlight the key events in a cycle of peace and conflict during a several-month period between the pastoralist communities in southwest Ethiopia/northern Kenya. All four groups discussed below retain strong customary institutions.

Spring 2011: An Ethiopian nongovernmental organization hosts a multiday intertribal peace meeting for the Daasanach, Nyangatom, and Hamar. The three groups agree to reconcile and make peace. Relationships are relatively calm.

Early August 2011: Daasanach kill 12 Turkana people, including nine women and two children, and steal a number of livestock. Turkana retaliate by attacking the Daasanach. Cumulatively, 33 people are killed in the clashes.

Early August 2011: Drought decreases the area of viable grazing land, and the Hamar and Daasanach begin grazing livestock along their shared group borders. With closer proximity and a state of peace in place, they begin regular visitation and trade with one another. Intergroup relationships are positive, and people visit each other across group boundaries with little fear of attack.

August 21–23, 2011: To solidify positive relationships in the face of bubbling disputes, the Ethiopian government organizes peace meetings between the Daasanach and Hamar. They engage in rituals in which they bury their weapons and agree to continued peace. The elders who are present state that anyone who causes conflict should be punished. A government official speaks at the proceedings, underscoring that peace will bring benefits to both groups. He also asks that the elders emphasize the importance of peace to the members of their communities. Finally, he stipulates that offenders will be punished as individuals (i.e., sentenced to prison) rather than through customary, community-based justice, which typically involves restitution through repayment of livestock.

August 30–31, 2011: Tensions have recently increased between the Daasanach and Hamar, so another peace meeting is held. The meeting includes traditional peace rituals in which sheep are slaughtered and their blood poured into holes that they have dug in the ground. The blood is covered with soil. Although sheep intestines are typically eaten, the peace ritual requires that they instead be buried in a separate hole, symbolizing that the Daasanach and Hamar have no hunger for conflict or revenge. The fat of each sheep is separated, and a Daasanach elder holds fat from a Hamar sheep and vice versa. Then, each hangs the fat around the other's neck, and they wash their bodies with a mix of water and milk. This symbolizes their reconciliation.

The next day, elders on both sides speak. The Hamar elder states: “…The youth are the ones who are killing and stealing so they should be careful not to create more problems. We will punish those who will not listen to us according to the laws of our culture. Therefore, what I want from now on is to live with the Daasanach as one.” The Daasanach elder replies: “All we want is peace, so after concluding this meeting we will gather and speak to the youth. We will punish anyone who does not listen to our words according to the laws of our culture.” A high-level representative from the Federal Government closes with the following remarks: “Don't think that you can kill and steal as you please like before. That is in the past. Now, a person who has done wrong will be prosecuted by law. Where you come from, when a person kills another he is awarded high honors by family and relatives. Their mother, father and wives become famous. That's why clashes continue. So women must stop doing such things, as it's their praise that leads men to committing crimes.”

Early September 2011: Despite the peace meeting several weeks earlier, tensions between the Hamar and Daasanach have increased. Another peace meeting is held on the border between Hamar and Daasanach to head off conflict. A Hamar elder begins, saying, “This land is ours. Why did you come here?.” The Daasanach elder replies, “This land is ours, not yours, so we can graze cattle where we want.” At this, young Hamar men in attendance pick up their AK-47s. Government administrators intervene, asking the Daasanach youth not to pick up their weapons. After tempers cool, the youth of both groups are sent away. The remaining elders cannot reach an agreement and decide to meet again at a later date.

September 17, 2011: While the Hamar and Daasanach are watering their cattle together at a common watering hole, a Daasanach man arrives and shoots and kills a Hamar man. The attacker then flees into the forest. The two groups separate their cattle and depart to their separate territories, and this is the end of their cograzing.

September 21, 2011: The Daasanach, Nyangatom, and Turkana have a peace meeting in Kenya.

September 24, 2011: Five Hamar youths take revenge for the death of the Hamar man earlier that month and kill a young Daasanach man tending cattle.

Fall 2011: Group relations continue in a similar cycle, fluctuating between conflict and peace.

4. The tensions between war and peace

The social dynamics leading to war and peace in small-scale societies are complex and societies are often in tension as their members struggle to balance the potential costs and benefits that can come from war and peace. The payoffs to war and peace vary by individual, the nature of conflict, and the specific out-group. Although war often imposes collective costs, nonparticipants, such as older adults may benefit from war if they can use it to satisfy their material or political goals and hence encourage young men toward war. Among pastoralists in East Africa for instance, male elders often receive a share of captured livestock thus creating an incentive for them to encourage youth to raid (Glowacki & Wrangham, Reference Glowacki and Wrangham2015) while in Big Men societies war may be used to advance the political or economic goals of individuals who then incite young men to war (Koch, Reference Koch1974; Meggitt, Reference Meggitt1977). Women may also sometimes benefit from offensive warfare, either from access to spoils, or the status that may come from being associated with a prominent warrior. At the same time, some individuals may benefit more from peace than others, either by using the peace process to advance their political or economics aims or establishing themselves as a prominent individual who is able to negotiate for peace (Wiessner, Reference Wiessner1998).Footnote 4 These competing tensions between war and peace create a complex social dynamic where individuals or factions may simultaneously benefit from war while recognizing the harms that come from increased warfare, including retaliation, loss of intergroup trade, and disruptions to their livelihoods (see Almagor, Reference Almagor, Fukui and Turton1979; Wiessner, Reference Wiessner2019, for detailed ethnographic descriptions of these tensions).

As decentralized societies begin to develop internal social structures, including age or status groups, or informal but powerful leadership either through groups of elders (gerontocracies) or specific individuals (Big Men, proto-Chiefdoms), the conditions in which war can be used to advance the strategic aims of the group become possible and can approach those found in state societies (Blattman, Reference Blattman2022; Schelling, Reference Schelling1980). For example, the Enga in Papua New Guinea have powerful Big Men who wield large amounts of influence and sometimes use war to advance the group's aims, including leveling imbalances of power when other groups began to gain an advantage. “Warfare was one means to counter unequal development by torching the schools or aid posts of neighbors, destroying coffee gardens and stores…” (Wiessner, Reference Wiessner2006, p. 181). When war is used to advance the aims of the group, then models of war that are typically applicable to states become more appropriate, including models that see war as arising from imbalances of power between groups or security dilemmas (Blattman, Reference Blattman2022; Posen, Reference Posen1993; Wagner, Reference Wagner1994).

5. State intrusion and peace

In the absence of strong mechanisms to prevent and resolve conflicts, especially ones robust enough to restrain the impulses of youth, it is extremely difficult for groups to achieve and maintain peace. Thus, many small-scale societies were often locked in cycles of tit-for-tat violence from which it was nearly impossible to escape. “Revenge raids often spiraled out of control and retaliatory actions assumed a pathological character” (Gabbert, Reference Gabbert2012, p. 238). The “Suri survivors do feel the loss and they do see the problem, but they don't know how to stop [it]” (Abbink, Reference Abbink2009, p. 33). “We tried to stop killing… then someone would kill and we would return to killing back and forth” (Boster, Yost, & Peeke, Reference Boster, Yost and Peeke2004, p. 481). Among the Waorani, “one group would invite another to a drinking feast where both would pledge to end their vendettas… The results were often disastrous… as likely as not the visitors would be ambushed on their way home by hotheads… There was, in short, no safe way to establish initial peaceful contacts between enemies or promote the growth of trust” (Robarchek & Robarchek, Reference Robarchek and Robarchek1998, p. 156). As a result, significant exogenous shocks that alter incentive structures are often necessary to precipitate the development of peace and contact with states is the most significant of these.

Contact with states and colonizing institutions, such as missionaries, is rightfully recognized as a destabilizing, and often destructive, force on indigenous societies, sometimes including short-term increases in violence as societies react to new pressures (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1988; Ferguson & Whitehead, Reference Ferguson and Whitehead1992). While states would often use violence to regulate the behavior of the groups they sought to control, there is overwhelming evidence that initial contact with states is often, with some exceptions, followed by a dramatic reduction in violent intertribal hostilities (Helbling, Reference Helbling2006; Helbling & Schwoerer, Reference Helbling and Schwoerer2021; Rodman & Cooper, Reference Rodman and Cooper1983). In South America among the mobile foraging Ache, for example, “What had been unthinkable when all the Atchei were living independently in the forest – their reconciliation… came about once they had lost their freedom” (Clastres, Reference Clastres1998, p. 100), while in the Arctic “some Yupiit believe that the Russians are really the only reason the Bow and Arrow wars ended” (Funk, Reference Funk2010, p. 557).

The reduction in intertribal violence is often viewed positively by community members. After the Australian government prohibited raiding among the Tiwi, “some of my older informants considered it a blessing when the pattern of sneak attack was terminated in 1912” (DeVore & Lee, Reference DeVore and Lee1968, p. 158). The Gebusi in New Guinea went from “intense intercommunity… lethal violence… to exhibiting a homicide rate that has dropped to zero” where “agents of colonial intrusion were seen as powerful benefactors if not saviors” (Knauft, Reference Knauft, Sussman and Cloninger2011, p. 220). In South America, “as they [the Waorani] began to realize that the feuding could stop, some members… began urging their kin to heed the words of the missionaries” (Robarchek & Robarchek, Reference Robarchek and Robarchek1998, p. 156). While among the foraging !Kung, “…many speak of the bringing of the molao (law) to the district as a positive contribution of the Batswana” (Lee, Reference Lee1979, p. 396).

States create several pathways to reduce intergroup conflicts. First, states often create formal conflict resolution mechanisms with coercive authority and apply sanctions to those who violate intergroup peace. Second, in small-scale societies, war is often an important or primary pathway to status and wealth and incorporation into state society provides a new arena to compete for wealth and status. Among the Bokondini with the arrival of colonial government, “the most important traditional avenue to becoming prominent was cut off…. The mission teachings, on the other hand… opened an alternative to gain prestige” and “it is likely… that they [young men] thought they would gain prestige by being active mission preachers” (Ploeg, Reference Ploeg, Rodman and Cooper1979, p. 176). Contact with states also imports new values that may provide an alternative to those that promote war. Among the Waorani, who previously had some of the highest rates of lethal violence for any society, “What they [missionaries] provided was new cultural knowledge – new information and new perceptions of reality – that allowed a reorganization of both cultural and individual schemata…they were able to imagine and to seek a new world, one without the constant fear of violent death. In a matter of months, the Upriver band abandoned the pattern of internal and external raiding that had persisted for generations” (Robarchek & Robarchek, Reference Robarchek and Robarchek1998, p. 157).

States also provide access to valuable new goods. For the Kutchin, “why did the two peoples stop fighting…? It is likely, that the natives… saw trading and trapping as more profitable than fighting” (Slobodin, Reference Slobodin1960, p. 90). For the Enga, peace followed shortly after contact, when the Australians “gave beads, salt, steel axes – everyone wanted it so they all followed the Kiap [Australians] and stopped fighting. We stopped fighting because we did not want to lose the source of these things” (Podolefsky, Reference Podolefsky1984, p. 75). In the Arctic “a desire for the newly arriving Western goods replaced the raiding parties with trading parties and hostilities… transformed into different forms of competition in the new economic situation” (Funk, Reference Funk2010, p. 557). Finally, among the Arbore of Ethiopia, “[new] developments also can be advantageous for the peace process, e.g., when new fashion items substitute for killing emblems, and when guns and bullets are sold on a large scale by young Arbore in order to buy mobile phones and pay their telephone costs” (Gabbert, Reference Gabbert2012, p. 244).

State institutions commonly allowed actors who were traditionally excluded by indigenous institutions, such as women and youths, to participate in the peace process (Fig. 3). For example, during a 2006 peace meeting in the Omo Valley, when women spoke to the groups assembled one reported “we are sick and tired of the attacks on us and our children… men solve their problem and later on the problem returns. We ladies are arguing… they should give us the chance [to make peace]” (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2008, p. 20). In Papua New Guinea, in the middle of a tribal battle “women walked into the middle of a battlefield between opposing sides…. They offered the men payments of foodstuff, money, cigarettes and soft drinks to lay down their arms. The women were members of a woman's club… associated with ‘governmental law’ and business, which were then seen as impartial yet powerful forces” (Henry, Reference Henry2005, p. 434).

Figure 3. Peacemaking in contemporary societies. Women and youths are typically excluded from customary forms of peacemaking in many societies. Contemporary peacemaking initiatives actively work to involve all sections of communities. At an intertribal peace meeting in the Omo Valley: (A) Nyangatom women speak about their desires for peace and (B) male youths indicate their desire for peace. Photos courtesy of Sylwia Pecio.

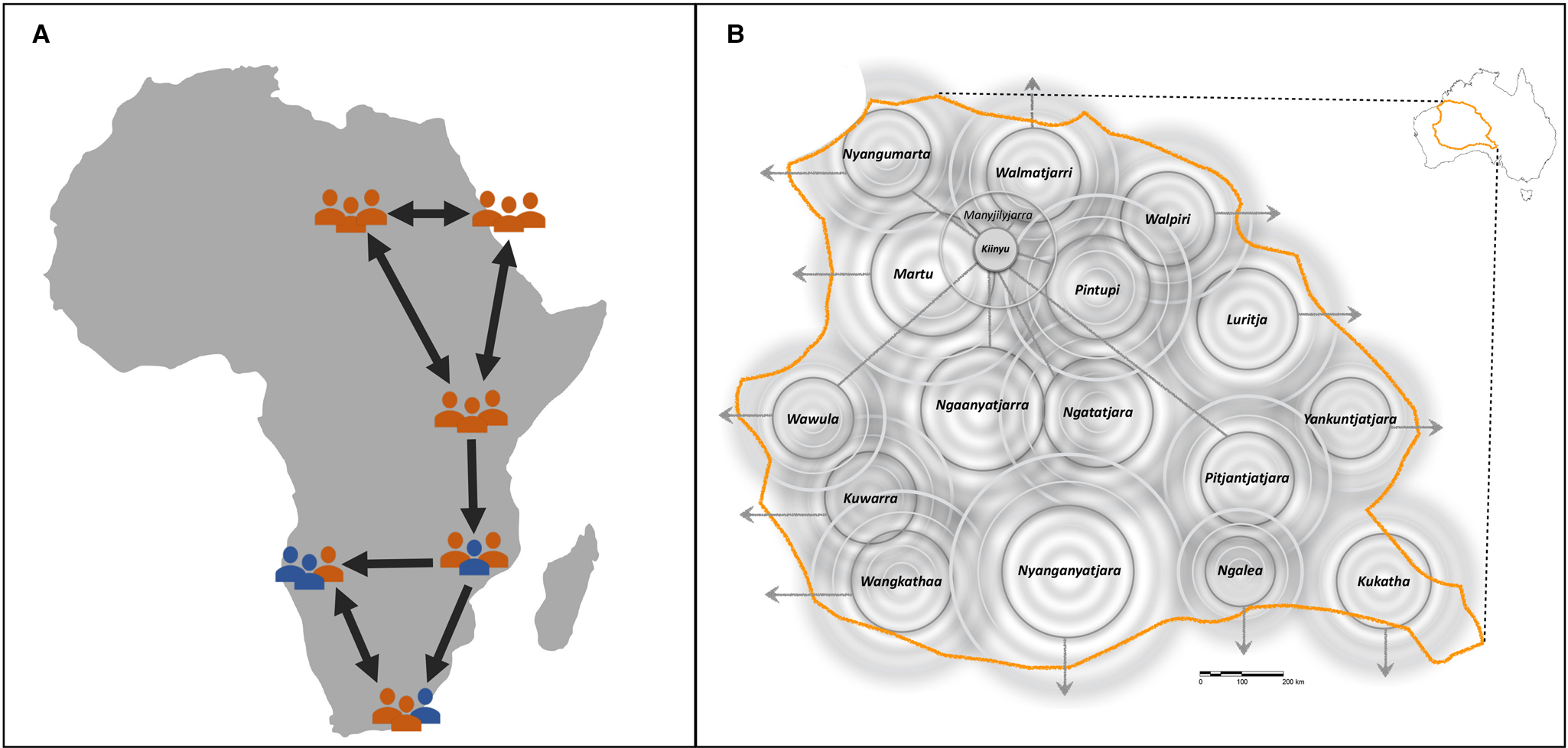

6. When intergroup cooperation and peace emerged

Despite the uncertainty regarding when war evolved in our prehuman ancestors, we can make tentative inferences about the development of cooperative and peaceful intergroup interactions among early humans based on archaeological and morphological evidence, studies of recent foraging groups, and game theoretical considerations such as those presented above. Did the last common ancestor have the capacity for tolerance toward strangers like bonobos, or exhibit reliable hostility and aggression like chimpanzees? The answer depends on which species makes a better model for the last common ancestor, if either Reference Glowacki2023, Reference Almécija, Hammond, Thompson, Pugh, Moyà-Solà and Alba2021; regardless, the fact that bonobos exhibit high levels of tolerance toward out-group members indicates that tolerance could predate the Homo lineage. The benefits of tolerant interactions would have greatly increased once humans developed the use of language, when interactions with nearby communities would have provided opportunities to share valuable information about territory, resources, or the behavior or location of other communities, or coordinate and plan activities such as group hunting or resource management (Wilson, Reference Wilson and Fry2013).

Paleoarchaeology provides clues as to when repeated cooperative intergroup interactions first became important in the human lineage, particularly through long-distance exchange networks. While the paleoarchaeological record reflects preservation bias and estimates are likely to be revised when new evidence emerges, it at least provides a baseline to date the development of cooperative relationships between groups (Tryon & Faith, Reference Tryon and Faith2013). Prior to 700,000 years ago, there is little evidence that our hominin ancestors engaged in or would have needed to engage in intergroup cooperation and avoidance of other groups was probably a common strategy due to the risk of being killed or injured in intergroup interactions. The fact that early Homo, unlike chimpanzees or bonobos, used sophisticated tools such as hand axes(Ambrose, Reference Ambrose2001), would have made intergroup interactions more perilous than in other primates, as a single individual from another group could inflict potentially lethal violence (Johnson & MacKay, Reference Johnson and MacKay2015).

The patterns of intergroup interactions began to change around 615–499,000 years ago, when early humans began to acquire lithic materials from more distant sources (Potts et al., Reference Potts, Behrensmeyer, Faith, Tryon, Brooks, Yellen and Renaut2018) with some evidence of occasional long-distance transport (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Asfaw, Assefa, Harris, Kurashina, Walter and Williams1984; Féblot-Augustins, Reference Féblot-Augustins1990). The increased reliance on nonlocal materials suggests that these early humans were expanding their ranges, becoming more likely to encounter and interact with other groups and creating benefits to sharing information about techniques and locations of materials.

6.1. Intergroup cooperation in the late Middle Pleistocene