1. Introduction

The water issuing from glaciers as a result of snow- and ice melt is a valuable resource. In Norway, as in other alpine areas, it is particularly important for hydroelectric power generation (Reference Østrem and HaakensenØstrem and Haakensen, 1999). Glacier-river discharge in summer is influenced by temporal and spatial patterns of snow accumulation in the preceding winter; these vary with altitude (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1998). Temporal and spatial changes of water inputs to a glacier, and of drainage-system configurations within it in response to those inputs, affect glacier dynamics (Reference Harper, Humphrey and GreenwoodHarper and others, 2002). For a variety of purposes, therefore, there is a need to understand the processes that determine both the time and duration of melting and the nature of the routes taken by the meltwater that passes through a glacier.

Recent studies have suggested that distributed and channelized systems coexist within and beneath a glacier (Reference Hubbard, Sharp, Willis, Nielsen and SmartHubbard and others, 1995; Reference Raymond, Benedict, Harrison, Echelmeyer and SturmRaymond and others, 1995), that the channelized system migrates headward during summer (Nienow and others, 1998) and that the systems close down in winter, with consequent temporary storage of water in the glacier and subsequent release in spring (Reference Kavanaugh and ClarkeKavanaugh and Clarke, 2001). Here, we examine how studies of oxygen isotopes in glacier-river water and its sources can help solve some of the problems associated with these ideas about glacier hydrology. Isotopes are ideal tracers of water sources and movement because they are integral constituents of water molecules, not solutes (Reference Kendall, Caldwell, Kendall and McDonnellKendall and Caldwell, 1998). Data from different years may differ markedly, reflecting differences of timing and location of melting and drainage-system configuration. Observations during a period of several years are likely to elucidate some of the problems associated with these differences.

Studies through a 16 year period at Austre Okstindbreen, the largest glacier of the Okstindan area, Nordland, Norway (Fig. 1), have focused on the following questions: (1) How do glaciers operate as hydrological systems over various time-scales? (2) Is there a distributed drainage system charged by snowmelt and a channelized system charged by ice melt? (3) Does the channelized system extend up-glacier during the course of the summer? (4) Is water stored temporarily in a glacier during the late part of the ablation season, the following winter and the early part of the next ablation season? (5) What are the fundamental controls of the isotopic composition of glacier-river water at Austre Okstindbreen? (6) What is the influence of climate and weather on these controls?

Fig. 1 The glacier Austre Okstindbreen, Okstindan, Nordland, Norway. Shallow ice divides link the head of the glacier and a number of smaller glaciers flowing east, south and west. (Map data: 1983.)

2. Oxygen Isotopes and Internal Drainage Systems at a Valley Glacier

2.1. Water sources

The water issuing from a glacier in summer is a mixture. Its sources include snow meltwater, glacier ice meltwater and rainfall (Fig. 2). Smaller contributions may come from melting firn, superimposed ice, regelation ice and ground-water. These sources differ in isotopic composition, and their relative contributions to total discharge are reflected in the composition of the river water emerging at a particular time. The contributions of each source vary on time-scales ranging from a few minutes, during discrete “outburst events”, to decades, within which major changes of glacier mass balance, driven by climatic variations, may be experienced.

Fig. 2 The water discharging in the glacier river in summer has a variety of sources of differing isotopic composition. Transit times from sites of input vary, as do the routes taken by the water in its passage through the glacier. The δ18O values of snow meltwater entering the glacier reflect both the initial, weather-dependent stratigraphic variations in the snowpack and the melting process. Snow meltwater, which passes slowly through the glacier from the higher part, provides the baseflow component that maintains river discharge throughout the summer. Glacier ice meltwater generally passes quickly through the lower part of the glacier, but may be trapped as conduits close down at the end of the melt season. Discrete events may result in sudden changes of glacier-river discharge and cause deviations of δ18O values of river water from a more regular pattern.

Both temporal and spatial variations of δ 18 O values characterize the snow which accumulates at a glacier in winter. Stratigraphic variations may be marked (Reference Moser and StichlerMoser and Stichler, 1975; Reference Shanley, Kendall, Albert and HardyShanley and others, 1995). In part, this reflects the large variations of winter air temperatures: in general, 18O depletion of falling snow increases with decreasing temperature (Reference He and TheakstoneHe and Theakstone, 1994; Reference McCabeMcCabe, 1994). The degree of turbulence in the air masses from which the snow falls (Reference Covey and HaagensonCovey and Haagenson, 1984) and rates of evaporation and condensation (Reference Peel, Mulvaney and DavisonPeel and others, 1988) also influence the δ 18 O values of accumulating snow.

The water that forms when melting occurs at the upper surface of the snowpack at higher altitudes may have to pass through several metres of accumulated snow. A wetting front may move down through the snow or, in the early stage of melting, water may move in unstable vertical channels (“flow fingers”), their size and distribution depending on the structure of the pack and on weather conditions (Reference SchneebeliSchneebeli, 1995). The development of finger flow aids warming of the snow when water refreezes at stratigraphic boundaries and ice layers form (Reference Marsh and WooMarsh and Woo, 1984). The thickness and frequency of such ice layers change as melting proceeds (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1998). When the snow-pack is wet and isothermal, they cease to grow, and no longer inhibit meltwater percolation (Reference Marsh and WooMarsh and Woo, 1985).

As meltwater percolates downwards, isotopic exchange occurs within the snowpack (Reference Cooper, Kendall and McDonnellCooper, 1998; Reference Unnikrishna, McDonnell and KendallUnnikrishna and others, 2002). The mean δ 18O value of the snowpack increases, and there is a trend towards greater homogeneity (Reference ArnasonArnason, 1969; Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1994, Reference Raben and Theakstone1998; Reference Raben, Theakstone and TørsethRaben and others, 2000). Meltwater entering the glacier from the snowpack is correspondingly depleted of 18O. Its δ 18O values are influenced by the processes which control snow metamorphism and the melting of individual strata, by those which determine transport pathways during percolation, and by those which control the interaction of the meltwater with the solid (ice) grains (Reference Taylor, Feng, Kirchner, Osterhuber, Klaue and RenshawTaylor and others, 2001).

At lower altitudes, the winter snow cover is thinner than at higher altitudes, and it directly overlies glacier ice. Snow meltwater enters the glacier earlier in the summer, at discrete points (moulins, crevasses). Because the snow cover is likely to be less depleted of 18O than that at higher altitudes, δ 18O values of the meltwater are higher than those of the snow meltwater that enters higher parts of the glacier.

The principal source of glacier-river water below the transient equilibrium line is glacier ice meltwater. Isotopic fractionation is not normally observed during the melting of glacier ice (Reference Moser, Stichler, Fritz and FonteMoser and Stichler, 1980; Reference Souchez and LorrainSouchez and Lorrain, 1991). Thus, δ 18 O values of glacier ice meltwater are similar to those of the compact ice from which it is formed (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1988b). However, isotopic changes may result from meltwater refreezing after it has percolated into the glacier (Reference Souchez and LorrainSouchez and Lorrain, 1991).

Rainfall may contribute to glacier-river discharge by way of large but short-lived events, or through more sustained periods of lower-intensity precipitation. The stable isotopes in precipitation are linked closely to the path, structure and evolution of the storm with which the precipitation is associated (Reference Gedzelman and LawrenceGedzelman and Lawrence, 1990; Reference Celle-Jeanton, Travi and BlavouxCelle-Jeanton and others, 2001). They are a measure of the average loss of moisture from the associated air mass between the source region and the precipitation site (Reference Rozanski, Araguás-Araguás, Gonfiantini, Swart, Lohmann, McKenzie and SavinRozanski and others, 1993). The isotopic composition of rainfall varies both between and within events (Gat, 1980; Reference Gedzelman and LawrenceGedzelman and Lawrence, 1982; Reference Rindsberger, Jaffe, Rahamin and GatRindsberger and others, 1990; Reference Pionke and DeWallePionke and DeWalle, 1992). The high within-event variability reflects both antecedent meteorological conditions and the fractionation processes which affect the atmospheric air masses with which the precipitation is associated (Reference DansgaardDansgaard, 1964; Reference Dansgaard, Johnsen, Clausen and GundestrupDansgaard and others, 1973).

2.2. Drainage systems

In recent years, studies of glacier hydrology and hydrochemistry have included a strong focus on the properties of glacier drainage systems (Reference Sharp, Richards and TranterSharp and others, 1998). Even when a glacier is relatively small, subglacial hydraulic systems may be complex (Reference FountainFountain, 1994; Reference Sharp, Brown, Tranter, Willis and HubbardSharp and others, 1995). A distinction is commonly made between “channelized” systems, with relatively large arborescent tunnels, and “distributed” systems, with many small passageways in a linked network at the bed (Fig. 2). However, drainage configurations may change in response to changing glacier geometry or water flux (Reference Fountain and VaughnFountain and Vaughn, 1995), and different types of drainage system may coexist within and beneath a particular glacier (Reference RichardsRichards and others, 1996; Reference Gordon, Sharp, Hubbard, Smart, Ketterling and WillisGordon and others, 1998). Dye-tracer tests may show very rapid or very slow throughput of water from different points at a single glacier (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1981; Reference Seaberg, Seaberg, Hooke and WibergSeaberg and others, 1988).

Below the transient equilibrium line, glacier-ice meltwater flows quickly across the bare ice surface. Having entered the glacier through moulins and crevasses, it may pass quickly to the point at which the river issues from beneath it. Water flow through snow is slow compared with that over bare ice (Reference FountainFountain, 1989). At lower altitudes in summer, the delay between peak meltwater input and peak glacier-river discharge may decrease as the snowpack becomes thinner. At higher altitudes, water may be stored temporarily in a saturated layer in firn, but the presence of such an aquifer depends on the underlying surface being relatively impermeable.

2.3. Changes during the summer

The relative contributions of different water sources to glacier-river discharge change during the course of the summer. At the same time, the glacier’s internal drainage systems evolve. Variations of glacier-river water δ 18O values result from these changes (Fig. 2). Glacier-river discharge is maintained by a baseflow component, the importance of which varies with geographical location, altitude, glacier size and glacier geometry (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996a). In periods of fine weather, diurnal variations of discharge are superimposed on the baseflow. In such conditions at Austre Okstindbreen, an 18O-depleted base flow component of discharge is diluted on a diurnal basis by a less depleted component (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1988b). In contrast to the relatively rapid passage of this water, the baseflow component is delayed within the glacier’s hydrological systems (Reference Tranter, Brown, Raiswell, Sharp and GurnellTranter and others, 1993, Reference Tranter1997; Reference Raymond, Benedict, Harrison, Echelmeyer and SturmRaymond and others, 1995).

The composition of glacier-river water may change as a result of changes of water routing within the glacier. A major alteration of the subglacial channel network at South Cascade Glacier, Washington, U.S.A., between 1987 and 1992 was indicated by isotopic data (B. H. Vaughn and others, unpublished information). Drainage of a glacier-dammed lake at Austre Okstindbreen, which disrupted pre-existing glacier drainage systems, caused short-lived departures of δ 18O values from a more regular pattern (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1978, Reference Theakstone2001; Reference Knudsen and TheakstoneKnudsen and Theakstone, 1988).

3. The Study Area

Austre Okstindbreen, which lies close to the Arctic Circle (Fig. 1), has an altitudinal range of 733 to >1600 m a.s.l., but only 0.2 km2 of the total surface area (14.0 km2) is above 1600 m. More than 10 km2 of the glacier is above 1250 m, the mean equilibrium-line altitude of recent years (Reference KnudsenKnudsen, 1995; Reference Jacobsen, Theakstone and KnudsenJacobsen and others, 1997). Between about 1200 and 1100 m, there is a heavily crevassed icefall. Above it, most of the firn and glacier ice remains covered by snow throughout the summer. In 1988, however, the specific net mass balance was negative up to the highest parts of the glacier, firn was widely exposed, and the whole of the accumulation area was seen to be heavily crevassed (Reference KnudsenKnudsen, 1989a). The crevasses must facilitate the entrance of meltwater into the glacier.

Austre Okstindbreen is bounded to the west and east by north–south-trending mountain ranges, but a valley, Leirskardalen, breaks the western chain. There, the glacier is exposed to westerly winds, resulting in a small area of net accumulation of snow at around 1000 m. A lake, Kalvtjørna, forms intermittently in Leirskardalen as water flowing from the valley is dammed by the glacier’s western margin. Austre Okstindbreen ends in the valley Oksfjelldalen, almost 2 km from the position occupied by the glacier front in 1908 (Reference Hoel, Hoel and WerenskioldHoel, 1962; Reference Andreasen and KnudsenAndreasen and Knudsen, 1985). During the last two decades, it has retreated through a proglacial lake, Bretjørna. The width of the retreating margin in the lake has decreased since the mid-1980s.

Glacier-river discharge was monitored at Austre Okstindbreen from 1976 until 1995 by members of the Okstindan Glacier Project, a collaborative programme of the Universities of Manchester, U.K., and Aarhus, Denmark. In the summers of 1976–86, two rivers usually issued from the front of the glacier. Sampling in 1982 revealed that the δ 18O values of their water differed: the larger river was considerably more depleted of 18O than was the smaller one. Generally, the northern river was the larger, but the southern one was the principal outlet for water throughout the summers of 1978 and 1981, and in the early part of the 1985 summer. In that year, drainage was disrupted during a mid-summer storm, after which the northern river was dominant (Reference KarlsenKarlsen, 1991). In 1987, no water issued from the southern side of the glacier, and in all subsequent summers only one river has discharged from its front.

Outbursts from the glacier-dammed lake Kalvtjørna occurred each summer from 1976 until 1988 (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1978; Reference Knudsen and TheakstoneKnudsen and Theakstone, 1988). The lake basin remained empty between 1989 and 1994, and water from Leirskardalen flowed into an open conduit beneath the glacier. The conduit apparently closed towards the end of the 1994 summer, and the basin again filled with water. Ice and snow covered the lake surface in early summer 1995, and Kalvtjørna drained on 8 and 9 July. The lake water made only a minor contribution to river discharge, but the event had a marked short-term effect on the glacier-river hydrograph and on the composition of the river water.

Annual mass-balance and glacier-river discharge studies were undertaken at Austre Okstindbreen between 1987 and 1995 (Reference KnudsenKnudsen, 1995). There is a close relationship between the glacier’s winter balance (snow accumulation) and the precipitation recorded at meteorological stations operated by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (DNMI) within 50 km of Austre Okstindbreen (Reference Raben, Theakstone and TørsethRaben and others, 2000). In November 1987, an automatic weather station was installed near the glacier, at 1350 m a.s.l. Severe winter weather resulted in occasional data gaps, and the station was removed in May 1989. Between October 1990 and February 1993, air temperatures were recorded at 3 hour intervals in the valley below Austre Okstindbreen (720 m a.s.l.). The correlations between mean daily temperatures close to the glacier and those recorded at the DNMI station Susendal (265 m a.s.l.) were high (1350 m: r 2 = 0.72, n = 243; 720 m: r 2 = 0.87, n = 311).

4. Methods

An automatic liquid sampler was used to collect water samples from the river as it emerged from beneath the glacier. The intake was maintained at a depth of about 0.5 m below the surface of the river; in most years, the river channel was 1.5–2 m deep at the site. Samples were transferred to randomly selected pre-numbered polyethylene vials and transported to the University of Copenhagen Department of Geophysics for mass-spectrometer analysis. Snow samples were collected from the walls of pits excavated to glacier ice or to the previous summer’s surface. They were allowed to melt in sealed polythene bags before being transferred to pre-cleaned vials. Ice samples collected at the glacier surface were treated in the same manner.

5. Results

5.1. Sources

a. Snow

Melting snow makes a substantial contribution to river discharge at Austre Okstindbreen. Much snowmelt occurs throughout the summer above the icefall, between 1200 and 1600 m a.s.l. Stratigraphical variations of δ 18O values in the pre-melt snowpack reflect weather changes during the winter (Reference He, Yafeng, Theakstone and TandongHe and others, 2001). Differences between sites are related, in part, to the altitudinal difference of air temperature. Because of the low winter temperatures, the snow generally is strongly depleted of 18 O, particularly in the higher parts of the accumulation zone (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1994). At the end of winter, any rapid change of air temperature is reflected by the quick descent of percolating water through the snowpack (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1998). Whilst mass-exchange processes in the free-water content, such as those associated with the formation of ice lenses, may obscure the fractionation effects accompanying percolation (Reference Moser, Stichler, Fritz and FonteMoser and Stichler, 1980), the mean δ 18O value of the snowpack increases as meltwater percolates downwards from the surface.

The range of δ 18O values of snow at Austre Okstindbreen is large (Table 1), both at a site and from one site to another (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1998). From 1987 until 1995, the snow cover was sampled each year in April/May, before the onset of melting. During subsequent melting, the mean δ 18O value of the residual snow tends to rise, and there is a trend towards greater homogeneity, indicated by the coefficient of variation of the samples at a site. This was evident at around 1240 m a.s.l., where samples were collected over periods of 8–11 weeks in five successive years (Fig. 3; Table 2). Heavy-isotope enrichment of the residual snow and underlying firn is characteristic of summer conditions at Austre Okstindbreen, and near-complete homogenization is likely to occur during the course of the melt season (Reference ArnasonArnason, 1969; Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1994, Reference Raben and Theakstone1998; Reference Raben, Theakstone and TørsethRaben and others, 2000). Water moving out of the pack is 18O-depleted. In the large area above the icefall, meltwater with a low δ 18O value enters the glacier through the firn.

Fig. 3 Changes in δ18O values of accumulated snow at around 1240 m a.s.l. on Austre Okstindbreen in five successive years. Sampling dates (year, month, day) are shown. Sample thickness varied from year to year, but the same thickness was used on each occasion in a particular year. The nature of the pre-melt isotope stratigraphy remains evident during the melting phase, but gradual homogenization is accompanied by a rise in the mean δ18O value (Table 2).

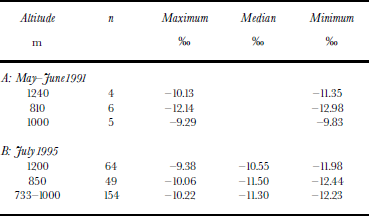

Table 1. Maximum, median and minimum δ18O values (‰) of sources of glacier-river water at Austre Okstindbreen (n = number of samples)

Table 2 Melting of the snow which accumulates directly on glacier ice at 1240 m a.s.l. (Fig. 3) usually starts in May. 18O enrichment of the pack is reflected in a rise in the mean δ18O value, and increasing isotopic homogenization results in an increase in the coefficient of variation (CoV: standard deviation divided by the mean). The snow melts completely before the end of summer

b. Glacier ice

The range of the δ 18 O values of 320 glacier ice samples collected at Austre Okstindbreen between 1985 and 1995 is relatively small, from −9.38‰ to −12.78‰ (Table 1), but there is some evidence of spatial variations. In 1985, ten samples were collected at the glacier surface, between the terminus (733 m a.s.l.) and the lower part of the icefall (∼1000 m a.s.l.): δ 18O values ranged from −10.48‰ to −12.78‰. In1987, seven paired samples of unweathered glacier ice and the overlying weathering crust were collected along a similar profile. Values ranged from −10.79‰ to −12.14‰, and at-a-site values of weathered and unweathered ice were similar (maximum difference: 0.53‰). In 1995, 154 samples of glacier ice were collected at the glacier surface along a longitudinal profile from the terminus to the lower part of the icefall; their δ 18O values ranged from −10.22‰ to −12.23‰. None of the three programmes revealed a clear altitudinal trend of δ 18 O values at the surface of the lower part of the glacier.

In May–June 1991, glacier ice samples were collected several times from beneath the winter’s snowpack at 810, 1000 and 1240 m a.s.l. On each visit, the snow pits were extended up-glacier by 1 m before the samples were collected. The samples from the 1000 m site, which was in the area of high local snow accumulation close to the head of Leirskardalen, were less depleted of 18 O than were glacier ice samples collected elsewhere at Austre Okstindbreen. The 810 and 1240 m sites were on the glacier centre line, and the ice at the lower site was more depleted of 18O than that at 1240 m a.s.l. (Table 3a). In July 1995, samples were collected on cross-profiles at about 850 and 1200 m a.s.l. In general, δ 18O values were lower at the lower altitude (Table 3b). The ice at 1200 and1240 m is likely to have formed from snow which accumulated relatively close to the equilibrium line. That exposed at 810 and 850 m probably originated in higher, and therefore colder, parts of the accumulation zone.

Table 3 Oxygen isotope composition of glacier ice samples collected in May–June 1991 and July 1995

δ 18O values of glacier ice meltwater are similar to those of the compact ice from which it is formed (Table 1). Isotopic changes may result from meltwater percolating into the glacier and then refreezing (Reference Souchez and LorrainSouchez and Lorrain, 1991). Reference Hubbard, Tison, Janssens and SpiroHubbard and others (2000) reported the presence of a layer of isotopically light ice about 12 m above the bed of Glacier de Transfleuron, Switzerland, and an isotopically heavy basal layer. Englacial samples were not obtained at Austre Okstindbreen. Subglacial observations have shown that regelation processes are active (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1988a), but have provided no evidence of widespread, large-scale refreezing of water at the bed.

c. Rain

The overall contribution of rainfall to river discharge at Austre Okstindbreen generally is small compared with that of melting snow and ice, but some precipitation events have a marked effect on discharge variations. Retreat of the glacier margins has exposed large areas of bare rock, from which run-off to the glacier during rainfall is rapid. The heaviest precipitation is associated with air masses arriving from the southwest, with a very short trajectory from the ocean to the Okstindan area, and its chemistry differs from that associated with air masses which arrive from the south, after a substantial passage across land (Reference Raben, Theakstone and TørsethRaben and others, 2000). Summer rainfall at Austre Okstindbreen, which can be both heavy and prolonged, is characterized by variations of the18 O/16 O ratio. The δ 18O values of the 60 samples of rainfall collected at the glacier between 1980 and 1995 ranged from −4.96‰ to −19.58‰ (Table 1).

Marked differences of δ 18O values characterized samples collected once daily during a period of heavy rain in July 1995 (Table 4). In several storms, the 18O content of the initial rainfall was higher than that of the rain which fell later (Table 5). Five samples were collected during each of two events: progressive 18O depletion was less marked during late-winter rainfall on 7–8 May 1993, when all the samples had high δ 18O values, than on 20 July 1992, when the rainfall was more depleted of 18O (Table 5). Because no single isotopic signature can be assigned to the rain falling on the glacier during a particular event, hydrograph separation based on a single (e.g. mean) value is unreliable (Reference McDonnell, Bonell, Stewart and PearceMcDonnell and others, 1990).

Table 4 Mean oxygen isotope composition of rainwater at Austre Okstindbreen, collected at 2200 h on successive days in 1995

Table 5 Oxygen isotope composition of samples of rainwater collected during events at Austre Okstindbreen. The time of sample collection is indicated

5.2. Within-season trends of glacier-river water δ 18O values

a. Year-to-year differences

Some 3400 samples of glacier-river water from Austre Okstindbreen were analyzed between 1980 and 1995. Studies suggested that the optimum spacing of sample collection was 2 hours, and, whenever possible, this was used from 1985 onwards. In 1985 and 1986, samples were analyzed twice, to assess the probable error of δ 18O values; the mean difference was 0.012‰ (standard deviation: 0.099‰). The duration of the study period was 15–41 days, except in 1992 (81 days overall) and 1995 (83 days overall), when sampling began in May rather than in July (Table 6). Some samples were collected in May 1993, but there was then no further sampling until July. The 1988 programme was limited by the loss of equipment caused by abnormal river discharge. In all other years from 1983 onwards, more than 130 samples were collected. Reference TheakstoneTheakstone (1988b) discussed data acquired between 1980 and 1987.

Table 6 Periods of glacier-river water sampling at Austre Okstindbreen

In most summers, the δ 18O values of the glacier-river water had a unimodal frequency distribution, with most samples in the range −12.5‰ to −13.5‰ (Fig. 4). The modal value differed from year to year: in 1990, it was −13.5‰ (i.e. −13.50‰ to −13.59‰), whilst in 1991 it was −12.9‰ (Fig. 4). The bimodal distribution of samples collected in 1985 was a consequence of a change of the glacier-river system during a mid-summer storm; δ 18O values of samples collected before and after the change each had a unimodal distribution. Samples collected in May and June, strongly influenced by snowmelt, generally were relatively enriched in 18O, with most δ 18O values below −13.0‰ (Fig. 5). Year-to-year differences of the mean isotopic composition of glacier-river water in summer and air temperatures in the preceding winter indicate the role of melting snow in maintaining glacier-river discharge: the mean δ 18O value of the river water tends to be higher after milder winters than after colder ones (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4 Frequency distributions of δ18O values (‰) of samples of glacier-river water collected at Austre Okstindbreen during successive summers. n is the number of samples.

Fig. 5 Frequency distributions of δ18O values (‰) of water samples collected in May–June in 1992, 1993 and 1995. n is the number of samples.

Fig. 6 Mean winter (October–May) daily temperature at Susendal and mean δ18O values of glacier-river water samples in the following summer at Austre Okstindbreen, 1984–95. Dates indicate the summer in which sampling was undertaken. Years 1986 (13 days), 1988 (7 days) and 1990 (14 days) are excluded because of the short duration of the period of continuous sampling.

The isotopic composition of the river water at a particular time in the summer is influenced by the degree to which the glacier’s drainage systems have developed; this differs from year to year (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996a). Variations of river water composition result in differences of extreme, quartile and median δ 18O values during periods of a few days (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Discharge of the Austre Okstindbreen glacier river, and maximum, minimum, quartile and median δ18O values of water samples collected during successive 3 or 4 day periods. Fifty per cent of the values lie within the interquartile range indicated by the shaded box. n is the number of samples. Occasional periods of 1 or 2 days in which no samples were collected are indicated.

b. The influence of mass-balance variations

Winter snow accumulation at Austre Okstindbreen in 1987/88 was below average, and the following summer was the warmest during the period 1980–95. Ablation rates were high, and the specific net mass balance was negative almost everywhere at the glacier (Reference KnudsenKnudsen, 1989a). Firn was widely exposed at the surface above the icefall. On several occasions when river discharge was high, blocks of ice were transported from beneath the glacier, possibly as a result of reorganization of the internal drainage systems (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996a). River discharge ceased abruptly on19 July. When discharge suddenly restarted shortly afterwards, the sampling site was destroyed.

In 1989, much of the lower part of Austre Okstindbreen still was covered by the previous winter’s snow in August. Discharge in mid-July remained below 4 m3 s−1, reflecting cold weather and low ablation rates. δ 18 O values generally were below −13.2‰ (Fig. 7). In contrast, the 1990 ablation season started early and ablation rates were relatively high. River discharge remained above 6 m3 s−1, with diurnal variations, until heavy rain fell on 21 and 22 July (Fig. 7). The river water was more depleted of 18 O than in the previous summer (Fig. 4). The summer balance was high in 1991 and 1993, and diurnal discharge variations were common. In both years, δ 18O values fell during periods of declining discharge, before rising as discharge subsequently increased (Fig. 7).

The wettest July on record in much of northern Norway was in 1992, and rain fell almost every day on the lower part of Austre Okstindbreen. At higher altitudes, however, much of the precipitation was of snow. With low ablation dominant, there was no significant increase of δ 18O values in the later part of the summer, and river discharge generally remained below 10 m3 s−1, without diurnal variations (Fig. 7). Heavy thunderstorms in July 1994 caused substantial melting of snow, and river discharge displayed marked peaks (Fig. 7). However, this followed a winter in which the winter balance (snow accumulation) at Austre Okstindbreen was less than in any other year between 1986/87 and 1994/95 (Reference KnudsenKnudsen, 1995) and δ 18O values were very low during fine weather.

5.3. Short-term variations of glacier-river composition and discharge

a. Diurnal variations

Diurnal variations of isotopic composition characterize glacier-river water in periods of fine weather (Reference BehrensBehrens and others, 1971). They reflect changing water inputs to the glacier’s drainage systems in response to variations of energy receipt at the surface. Reference TheakstoneTheakstone (1988b) reported a 6 hour lag between variations of air temperature and the δ 18O values of glacier-river water at Austre Okstindbreen. The diurnal variations may be superimposed on longer-term trends of increasing or decreasing δ 18O values (Fig. 8). In all cases, the diurnally varying source is less depleted of 18O than is the baseflow component. Both the peak δ 18O values and the transit time indicate that glacier-ice meltwater is a significant element of the non-baseflow component.

Fig. 8 (a) Diurnal variations of δ18O values, with morning minima and afternoon/evening maxima, were superimposed on a rising trend between 20 and 24 July 1993. (b) Diurnal variations of δ18O values accompanied a rising trend between 19 and 22 July 1994.

b. “Spring events”

In each of the three years when sampling was carried out at the beginning of the melt season, there were brief periods in which δ 18O values rose sharply. The glacier’s poorly developed drainage system probably was unable to accommodate the input of water from snowmelt. In 1992, sampling started on 25 May. On 28 May, δ 18O values increased rapidly, before falling again (Fig. 9a). The peak value (−12.01‰) was >1‰ above that of the sample collected 13 hours before. In 1993, sampling started on 16 May; δ 18O values increased from −13.15‰ to −12.40‰ in the first 26 hours, and then fell to −13.17‰ at midday on 19 May (Fig. 9b). In 1995, δ 18O values increased from −13.44‰ to −12.56‰ between 0900 and 2300 h on 3 June (Fig. 9c) and it was not until 5 June that the δ 18O values of water emerging from the glacier returned to the pre-existing pattern of low-amplitude, 18O-depleted variations. It is likely that, in the reorganization of the drainage system consequent upon the sudden increase of supply, water which had been trapped within or below the glacier during the previous year’s close-down was released from storage.

Fig. 9 (a) An abrupt increase of δ18O values on 28 May 1992 occurred as water was being released from storage within Austre Okstindbreen. (b) A rapid rise in δ18O values on 16 May 1993 marked the probable release of stored water from Austre Okstindbreen as the glacier’s drainage system was reorganized. (c) δ18O values of the water discharging from Austre Okstindbreen increased quickly on 3 June 1995, probably as stored water was released from within or beneath the glacier. The low δ18O values before and after the event reflected the influence of melting snow.

c. Water release from storage

During most summers at Austre Okstindbreen, there were short-lived departures of glacier-river water δ 18O values from a more regular pattern. In dry weather on 20 July 1990, glacier-river discharge rose rapidly, reaching 11 m3 s−1 in late afternoon, after several days in which it had been only 7–8 m3 s−1 (Fig. 10). δ 18O values fluctuated, but on a rising trend (−13.60‰ at 0600 h to −13.24‰ at 2100 h). Discharge remained high, although with brief fluctuations, throughout the night of 20–21 July, and δ 18O values remained above −13.5‰. Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen (1996a) reported that the suspended-sediment concentration in the river increased considerably on 20 July, but that concentrations of ions with a probable subglacial origin were unaffected. It is likely that water was released from a reservoir or conduit within or beneath the glacier that previously had not been connected to the main drainage system.

Fig. 10 River discharge (continuous line) rose rapidly in dry weather on 20 July 1990, and increased again after the onset of heavy precipitation during the morning of 21 July. As rainfall continued, δ18O values fell sharply, probably because of exhaustion of the supply of stored, 18O-enriched water released during the first phase of the event.

δ 18O variations during the last 2 weeks of sampling in 1995 (3–16 August) were of unusually large amplitude, with a cycle of about 72 hours, during each of which δ 18O values increased dramatically for 12–18 hours (Fig. 11). The variations, superimposed on a general trend of increasing values, were remarkably similar in form to those of river discharge. On several occasions, discharge rose very sharply and then declined for 2 or 3 days, with minor increases occurring during the afternoons (e.g. 4, 6 and 7 August) (Fig. 11). It is evident that there were a number of episodes in which the depleted baseflow component of discharge was diluted by sources richer in 18O, and that these alternated with longer periods in which the contribution of 18O-enriched water became much less significant. Sampling in 1995 was continued until later in the ablation season than in previous years, and the 18O-rich water may have been stored within the glacier since the last part of the previous summer. Partial closure of the glacier’s drainage systems occurs in late summer whilst surface melting of glacier ice continues to supply 18O-rich water. Some of the water originating from such melting in 1994 probably was trapped within the glacier until it was released by expansion of the drainage systems in August 1995. The sudden release of the stored 18O-enriched waters might have caused an abrupt shut-down (Reference Truffer, Echelmeyer and HarrisonTruffer and others, 2001), or the supply might have been exhausted, resulting in a decline of δ 18O values of glacier-river water until further extension of the internal drainage systems tapped another source of stored water. It is evident that, at the minimum stages, river discharge was provided largely by the 18O-depleted baseflow.

Fig. 11 Pronounced variations of δ18O values of glacier-river water between 3 and 16 August 1995 had a cycle of around 3 days. Glacier-river discharge variations (continuous line) were similar to those of δ18O values, suggesting that supplies of 18O-enriched water were being tapped periodically by the glacier’s drainage systems. The peak δ18O value during each episode was within the range of glacier ice and meltwater values (Table 1).

d. Rainfall-induced events

Major disruption of glacier-river flow during summer storms has occurred on several occasions at Austre Okstindbreen. During heavy rainfall on 22 July 1985, one of the two rivers previously issuing from the glacier ceased to flow, and the discharge of the other increased markedly (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1989). The δ 18O values of samples from that river were lower after the event than before it, suggesting that it received greater contributions from melting snow after the drainage diversion.

A major precipitation event, during which 60 mm of rain fell in 36 hours, began at 1000 hours on 21 July 1990. River discharge increased quickly, to about 15 m3 s−1 at 1600 h, and remained around that value until the evening of 22 July (Fig. 10). It then declined rapidly, falling to about 10 m3 s−1 at midnight on 23–24 July. Sampling, which had been interrupted briefly, was restarted at 1500 h on 21 July. δ 18O values fell sharply that evening, and then remained around −13.5‰ through the rest of the event. Precipitation alone could not account for the increased discharge. Evidently, a source of stored englacial or subglacial water, relatively enriched in 18O, had been tapped immediately before rainfall started. This may have been sufficient to help maintain an outflow of around 11 m3 s−1 for 17 or 18 hours, but it must have been exhausted before the end of the precipitation event. The decline in δ 18O values during and, particularly, after the last part of that event (Fig. 10) indicates that much of the water leaving the glacier at that time was depleted of the heavy isotope.

On 28 July 1991, glacier-river discharge increased from 9 to 19 m3 s−1. δ 18O values, which had varied around a mean of −13.01‰ on the previous day, rose rapidly to −12.17‰ at 1800 h (Fig. 12). A total of 9 mm of precipitation was recorded at a rain gauge close to the glacier, at 830 m a.s.l. However, rainfall is unlikely to have caused the whole of the increase in discharge: Reference KnudsenKnudsen (1992) calculated that around 70 mm would have been required. The 18O content of rain which fell on 27 July was very high (Table 5), but that rain was neither heavy nor prolonged, and δ 18O values of glacier-river water did not increase until the following day. Whilst enhanced melting of snow and ice during the storm may have contributed to the higher discharge, it is apparent that some water was displaced from storage within the glacier. Falling discharge and δ 18O values through 29 and 30 July were interrupted by afternoon increases, and the pattern of diurnal variations was repeated on a larger scale on 31 July (Fig. 12). The overall decline in δ 18O values from midnight on 28 July until midday on 30 July is indicative of the “shutting-off” of a previously stored source of water.

Fig. 12 δ18O values of glacier-river water rose on 28 July 1991 as discharge (continuous line) doubled in 24 hours. Displacement of water from storage within the glacier may have been responsible for the rapid rise in δ18O values.

Diurnal variations of δ 18O values, with an early-morning minimum and a late-afternoon maximum, were interrupted when rain began to fall on 22 July 1992 (Fig. 13). River discharge increased very rapidly and remained high until a sharp decline on 24 July. Marked fluctuations of δ 18O values, superimposed on a generally declining trend, occurred for about 48 hours from midday on 23 July (Fig. 13). The major fluctuations occurred somewhat later than the worst weather. The pulses of 18O-enriched water leaving the glacier may have resulted from storm water reaching the bed, causing subglacial channels to enlarge and to tap sources of stored water.

Fig. 13 A marked increase of glacier-river discharge (continuous line) resulted from rainfall on 22 July 1992. High δ18O values on 23 and 24 July probably were caused by the release of pockets of stored water as subglacial conduits expanded.

e. Glacier-dammed lake drainage

The glacier-dammed lake Kalvtjørna has formed and drained in many recent summers. Several outbursts have occurred during or immediately after heavy rain. Others have been associated with periods of rapid snowmelt (Reference Knudsen and TheakstoneKnudsen and Theakstone, 1988). The lake drained during a period of wet weather on 7–8 July 1995, causing river discharge to increase; the peak occurred late on 8 July. δ 18O values rose as outflow from the lake increased, reaching a maximum at about midnight on 8–9 July (Fig. 14). Brief, but marked, fluctuations of discharge occurred shortly after the culmination of the event, probably as a result of temporary obstructions (collapse) of the drainage system between the lake basin and the river outlet. However, the 2 hour sampling interval was too large for the fluctuations to be identifiable in the δ 18 O record. Discharge declined sharply on 9 July as the lake basin was emptied, and δ 18 O values fell for around 36 hours. The variations of discharge and isotopic composition were very similar (Fig. 14). This indicates that the lake water, and water formed by melting of conduit walls between the lake basin and the outlet from the glacier, was less depleted of 18O than was the rest of the water which contributed to river discharge. The water discharging from Austre Okstindbreen as Kalvtjørna drained through the glacier in 1984 also was relatively rich in 18O (Reference Knudsen and TheakstoneKnudsen and Theakstone, 1988).

Fig. 14 δ18O values of glacier-river water rose as the glacier-dammed lake Kalvtjørna drained on 8 July 1995, indicating that the lake water was relatively enriched in 18O. River discharge (continuous line) and δ18O values declined on 9 July as the lake basin was emptied.

6. Discussion

a. Ice-melt and snowmelt contributions to glacier-river discharge

The mean δ 18 O value of the river water emerging from Austre Okstindbreen in summer (−13.15‰, 3398 samples) is well below that of glacier ice, and it is clear that other sources, with a relatively low 18O content, contribute substantially to discharge. Variations of glacier-river discharge and oxygen isotopes display striking similarities at both short (hours) and long (days) time-scales. Diurnal cycles reflect varying melt rates of glacier ice through the day, caused by changing energy inputs at the surface. Glacier-ice meltwater, with a relatively high δ 18O value, dilutes the “lighter” baseflow in response to increased surface melting. Much of the water formed from glacier ice passes quickly through Austre Okstindbreen. Dye-tracer tests and direct observation have demonstrated the existence of conduits within, and at the bed of, the glacier (Reference Knighton and TheakstoneKnighton and Theakstone, 1978; Reference Knudsen and TheakstoneKnudsen and Theakstone, 1981).

One possible source of the baseflow component of glacier-river discharge is basal ice, formed by accretion of material from the bed or by metamorphic processes within the ice close to the bed (Reference KnightKnight, 1997). Reference Hubbard and SharpHubbard and Sharp (1993) suggested that extensive spatial and temporal fractionation associated with the formation of basal regelation ice layers could account, in part, for the isotopically light baseflow at Austre Okstindbreen. Basal ice may be isotopically heavier than both “unaltered” englacial ice and snow at the glacier surface (Reference Hubbard and SharpHubbard and Sharp, 1995; Reference Iizuka, Satake, Shiraiwa and NaruseIizuka and others, 2001). A variety of basal ice formations is present at the bottom of Austre Okstindbreen (Reference TheakstoneTheakstone, 1988a), and some basal ice does form as water freezes within cavities beneath the glacier (Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1983). However, basal ice does not outcrop at the glacier margins, and no evidence has been found of a thick layer of metamorphosed ice caused by widespread, large-scale refreezing at the glacier. Furthermore, the composition of any basal ice and regelation-related meltwater at Austre Okstindbreen should differ little from year to year. Thus, it is unlikely that fractionation associated with refreezing of water at the bottom of the glacier would result in a baseflow component of discharge which varied significantly from one summer to another. The between-year differences of that component (Fig. 4) require another explanation.

Throughout the summer, considerable snowmelt occurs above the icefall, at 1200–1600 m a.s.l. Because of the low winter temperatures, the snow generally is strongly depleted of 18O, particularly in the higher parts of the glacier’s accumulation zone (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1994). Surface melting is accompanied by homogenization and 18O enrichment of the residual snow, and water moving out of the pack is 18O-depleted; meltwater with a low δ 18O value enters the glacier through the firn. As melting proceeds, isotopic homogeneities within the pack continue to be smoothed out, and the increase of the mean δ 18O value of the residual snow is maintained. Solute load calculations indicate that it takes several weeks for the first meltwater generated at the surface of the highest parts of the glacier to reach the terminus (Reference Raben and TheakstoneRaben and Theakstone, 1997). Nevertheless, snowmelt is the principal source maintaining the summer flow of water from the glacier when ablation rates are at a minimum and river discharge is low (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996b). For much of its passage through the glacier, the snow meltwater must occupy a “distributed” drainage system, with small passageways in a linked network smoothing out some of the variations of inputs.

6.2. Water storage within the glacier

Reference KnudsenKnudsen (1989b) reported that, during six successive summers, 1982–88, a considerable proportion of the discharge of the Austre Okstindbreen glacier river was not accounted for by ablation and precipitation, but was caused by the release of water from temporary storage. Dye-tracer tests showed that, whilst some water passes rapidly through the glacier from points of entry at the surface, considerable delays characterize throughflow from many points (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1981). Oxygen isotope data have confirmed that much water may be stored, both within the glacier and at the bed. Water is likely to be trapped in or beneath the glacier as inputs decline towards the end of summer (Theakstone, 1985). Cavities separated from the general drainage network can be created by conduit closure, possibly aided by freezing. Englacial voids, originating from, or connected to, the internal drainage system, also may exist; they are common in the upper ablation area of Storglaciären, Sweden, a much smaller glacier than Austre Okstindbreen, with a complicated internal drainage system varying both spatially and temporally (Reference PohjolaPohjola, 1994; Reference Hanson, Hooke and GraceHanson and others, 1998). Storage also may occur in the icefall, although crevasses there may provide water-input routes to the internal drainage system. Radio-echo sounding has shown that slightly overdeepened zones exist beneath the lower part of Austre Okstindbreen, and an overdeepened basin has been identified beneath the accumulation area (Reference Theakstone and JacobsenTheakstone and Jacobsen, 1997). These may provide additional sites for water storage.

6.3. Development of the glacier’s drainage systems

Water storage at Austre Okstindbreen, and hence the composition of the glacier-river water, is influenced by the efficiency of the glacier’s drainage systems, and the speed with which they develop. At the end of winter, the active drainage systems within and beneath the glacier are likely to be poorly developed, with a limited capacity to store or transmit water. Snowmelt begins some weeks earlier, and the melt rate is more rapid, on the lower parts of Austre Okstindbreen than at higher elevations. Water passes more quickly through the glacier where the snow is underlain by ice than where there is a large thickness of firn. Melting of the snowpack on and around the lower part of the glacier, especially if it is rapid, can supply a substantial amount of water. If the input of meltwater exceeds the drainage systems’ capacity, instability and reorganization may result (Reference Kavanaugh and ClarkeKavanaugh and Clarke, 2001). This was apparent in May 1992, when major ionic changes accompanied isotopic variations in glacier-river water (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996b). Similar events in 1993 and 1995 (Fig. 9) resembled the “spring events” caused by early-summer melting at other glaciers (Reference Stone and ClarkeStone and Clarke, 1996; Reference Gordon, Sharp, Hubbard, Smart, Ketterling and WillisGordon and others, 1998; Reference Anderson, Fernald, Anderson and HumphreyAnderson and others, 1999).

The summer’s weather has a significant role in determining the amount of water entering Austre Okstindbreen and, therefore, the speed with which the glacier’s internal drainage systems develop (Reference Theakstone and KnudsenTheakstone and Knudsen, 1996a). This development varies markedly from year to year. Subglacial channels exist beneath the lowest part of the glacier early in the summer, when water issues in one or two rivers. Subsequently, as the internal conduit systems extend, the capacity for rapid throughput of water increases. In the upper part of the ablation area and above the icefall, however, where water passes through the glacier more slowly, temporary storage is probable. Crevasses in firn are widespread at Austre Okstindbreen, and may contribute to water storage within the glacier, as at South Cascade Glacier, Washington, U.S.A., where englacial water-filled voids develop as burial and transport of crevasses closes the contact with the surface (Reference FountainFountain, 1989).

As the summer progresses, increased water input, from rainfall, meltwater or the drainage of the glacier-dammed lake, must result in reorganization of the drainage systems within Austre Okstindbreen. Subglacial channels can change significantly during storms, as rainfall causes discharge to increase and cavities to expand when pressure rises (Reference Gordon, Sharp, Hubbard, Smart, Ketterling and WillisGordon and others, 1998; Reference Mair, Nienow, Willis and SharpMair and others, 2001). Such events occurred in 1985, when one of the two rivers issuing from the glacier ceased to flow, and in 1988, when the sampling station was destroyed. During significant water input events, connections are established between parts of the drainage systems which previously were discrete; afterwards, cavities are likely to be more interconnected (Reference CutlerCutler, 1998). Channelized flow is likely when water drains from the ice-dammed lake, Kalvtjørna, because the system then has access to much more water than usual (Reference AlleyAlley, 1996).

Smaller conduits probably are opened when water pressure is high, and major water-pressure events may cause a proportionally greater increase in conduit capacity (Reference Hanson, Hooke and GraceHanson and others, 1998). Water storage conditions at the bed also may change as water drains from a cavity, or from the glacier-dammed lake, Kalvtjørna; locally, the glacier may be lifted from its bed by over-pressurizing of the drainage system (Reference Truffer, Echelmeyer and HarrisonTruffer and others, 2001). Observations at Austre Okstindbreen have provided evidence of rainfall displacing water with a relatively high δ 18O value (Fig. 12). Reference Van de Griend and ArwertVan de Griend and Arwert (1983) noted that the water leaving the 3.76 km2 Neves glacier, Italy, during the early stages of a storm consisted mainly of “pre-storm” water, with a low δ 18O value, displaced by the rainfall. Rain falling higher up the glacier infiltrated the firn and underlying glacier ice, and the travel time of water from this “recharge area” was significantly longer than that from the glacier tongue.

Towards the end of summer, as parts of the glacier’s drainage systems are closing, surface melting at the lower part of Austre Okstindbreen continues to supply 18O-rich water. Some of this cannot pass through the glacier, and is trapped within it. This water is not tapped until late summer of the following year, when the up-glacier extension of the drainage systems and the position of the transient equilibrium line (snowline) are close to their maximum (Reference RichardsRichards and others, 1996). By then, surface melting is decreasing and “normal” river discharge is maintained largely by the 18O-depleted baseflow component. Accordingly, when the source of stored water is exhausted, the δ 18 O value of the glacier-river water falls to a minimum (Fig. 11).

7. Conclusions

The isotopic composition of the water issuing from a glacier in summer is determined, in part, by climatic conditions. δ 18O variations of the glacier-river water at Austre Okstindbreen display some similarities from year to year, but there is neither a “typical” summer, nor a “representative period” within a summer. In all years, melting snow makes a substantial contribution to glacier-river discharge. Snow accumulation in a cold winter is relatively low, and the snowpack is more depleted of 18O than is the thicker pack that accumulates in a warmer winter. In summer, surface melting and meltwater percolation cause progressive homogenization of the pack. The initial stratigraphic variations of δ 18O values, themselves a consequence of winter weather, are smoothed out, and the mean δ 18O value rises. Water draining from the base of the pack is more depleted of 18O than is the residual snow. Towards the end of the summer, the mean δ 18O value of the remaining snow is much higher than at the onset of melting, and water draining from the pack has a higher 18O content than early in the summer.

At the start of the melt season (mid-May to early June at Austre Okstindbreen), river discharge is supplied principally by snow melting on and around the lower part of the glacier. The melt may provide more water than can be accommodated by the poorly developed, low-volume drainage system, leading to instability. The water released from the glacier during such events has a high δ 18O value, indicating that its probable sources are glacier ice or snow that accumulated at a relatively high temperature.

In a warm summer, the snowline moves up-glacier quickly, exposing increasing amounts of glacier ice to melting. Meltwater with a high δ 18O value enters the glacier through crevasses and moulins, passes rapidly through it in channelized systems, and emerges in the glacier river within a few hours. Diurnal variations of δ 18O values accompany variations of glacier-river discharge. In the later part of the summer, headward extension of the channels may tap water stored within the glacier since the previous summer’s closedown. The stored water, formed by melting glacier ice or by late-summer melting of the residual snow cover, is likely to have a relatively high δ 18O value.

In a cool summer, the thinning snowpack may survive far into the season, limiting the input of glacier ice meltwater to the glacier’s drainage systems. The baseflow component of river discharge, maintained by snowmelt, is relatively large. Moving through a “distributed” drainage system, the snow meltwater smooths out variations related to changing inputs. The internal drainage systems close down at the end of the melt season. There is no discernible discharge of water from Austre Okstindbreen in winter (October–April/May). Any water formed by basal melting is likely to remain beneath the glacier, stored in isolated cavities or sediments at the bed.

The direct contribution of rainfall to glacier-river discharge at Austre Okstindbreen generally is small compared to the summer inputs of melting snow and melting ice. However, rainfall events can have a marked effect on glacier-river discharge, in part by displacing water from storage or by causing changes of the drainage systems within the glacier. δ 18O values of rain vary both between and within events and, hence, their effect on glacier-river δ 18O values is unpredictable.

Drainage of the glacier-dammed lake, Kalvtjørna, may result from headward extension of channelized systems within the glacier. However, many of the events have followed a period of increased water inputs from enhanced melting or rainfall, and it is possible that over-pressurizing of the drainage system lifts the glacier from its bed. Rapid emptying of the lake indicates that the water passes through a channelized system. The δ 18 O values of water discharging from Austre Okstindbreen as Kalvtjørna drains suggest that the lake water is relatively enriched in 18 O; glacier ice melting from conduit walls during the events also contributes to the high δ 18O values. Isotopic variations in glacier-river water during such discrete events provide useful information, supplementing that provided by systematic observations carried out through the melt season.

Acknowledgements

Isotope analyses of samples collected at Austre Okstindbreen since 1980 have been carried out at the Copenhagen Geophysical Isotope Laboratory; I am very grateful for the laboratory’s support of the Okstindan Glacier Project. I wish to thank N.T. Knudsen of the Geological Institute, University of Aarhus, Denmark, for collaboration in the field over more than two decades, and for countless discussions about the results of the observations at Austre Okstindbreen. I am grateful for the assistance with water sampling provided by N. Bendtsen, C. Borre, T. Eriksen, M. Halkjær, He Yuanqing, H. Hove, F. Jacobsen, J. Jacobsen, M. B. Knudsen, P. Raben and L. Thomsen. I thank N. Scarle for assistance with the figures. Suggestions from M. Tranter and an anonymous reviewer improved the paper considerably. The Scientific Editor, D. Peel, provided much-appreciated assistance. The research was supported by the U.K. Natural Environment Research Council (research grants GR3/3693, GR3/7253 and GR3/8373). Additional support was provided by the Norwegian Energy Corporation (Statkraft), the Royal Society, the British Council, the Leverhulme Trust and the Manchester Geographical Society.